This article discusses Pieter Bruegel’s Tower of Babel (now in Vienna), originally displayed in the suburban villa of Antwerp entrepreneur Niclaes Jonghelinck as an image that fostered learned dinner conversation (convivium) about the well-being of the city. Looking at various sources, the author analyzes how the theme of the painting, a story of miscommunication and disorder, resonated with the challenges faced by the metropolis. Antwerp’s rapid growth resulted in the creation of a society characterized by extraordinary pluralism but with weakened social bonds. Convivium was one of the strategies developed to overcome differences among the citizens and avoid dystrophy of the community.

“Come, let us make a city and a tower”: The Tower of Babel and Convivial Conversations in Mid-sixteenth-Century Antwerp

On February 21, 1565, Antwerp banker and merchant Niclaes Jonghelinck pledged to the city, on behalf of his business partner Daniel de Bruyne, the art collection displayed in his suburban villa, Ter Beke. The transaction required the compilation of a detailed inventory of paintings, one of the few in the period, which included artists’ names. The document mentioned many works, including several allegorical and mythological compositions by Frans Floris and Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Procession to Calvary, his series the Months, and the Tower of Babel (fig. 1).1 It is this last painting, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, on which this article focuses. The inventory did not specify the location of the panel, nor do we know the layout of Jonghelinck’s residence, which would be crucial for determining this location. Nevertheless, scholars have persuasively argued that the Months were displayed in the dining hall and functioned as active backdrops for dinner parties hosted by the banker.2 Following this identification, I propose that theTower of Babel shared the space with those six panels: they were prestigious commissions from one of the most distinguished and leading contemporary artists, almost identical in their exceptionally large size, and, most importantly, related both to the activities taking place in the room and to Antwerp’s current circumstances.3

Collectively, the paintings crafted the public identity of their owner as a sophisticated, wealthy, and well-educated citizen, concerned, as we shall see, with the fate of his community. They conformed to the period ideal of decorum: the production of food shown in the Months was not only related to Antwerp’s agriculture in general but also to the food that would be consumed by guests dining with Jonghelinck, while the theme of the changing seasons and the cycle of nature reinforced the suburban location of the residence.4 However, nourishing the body was only one purpose of the banquets. The second, and arguably more important, was nourishing the mind and the soul through convivial conversations often occasioned by paintings.5

The story of the Tower of Babel is, metaphorically, a perfect antithesis of this objective: one of its central themes is the miscommunication caused by the introduction of multiple tongues, which eventually led to the fall of a once-successful kingdom. While the narrative exemplifies the dangers of the lack of discussion, Bruegel’s composition facilitates a learned conversation. The biblical account moves from the unity of languages to their separation, whereas convivium helps to overcome the differences inherent in a diversified community, in order to create a harmonious society founded upon Christian values. In addition, unlike the biblical story, the custom accommodates a variety of opinions and discourses, finding them profitable and enriching rather than threatening.6 The Months visually articulated the agricultural prosperity of the Brabant countryside and decorously complemented the primary function of the room. The Tower of Babel provided an equally decorous Old Testament example of the dangers of miscommunication, urging those participating in a meal gathering to answer the question of how to maintain prosperity in a community characterized by extraordinary pluralism. It presented an open-ended visual argument, which stimulated discussion and self-examination. In this essay, I correlate the painting with contemporary mercantile and demographic circumstances in Antwerp, offering a reading of this well-known composition within the framework of convivial tradition and informed by period commercial and social discourses.7

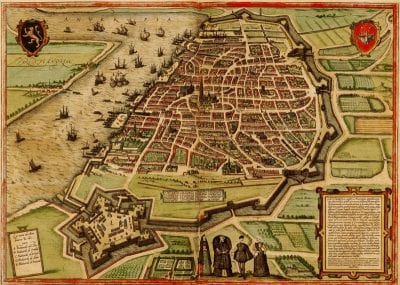

In the sixteenth century, Antwerp underwent rapid and unprecedented processes of economic and demographic growth. This was accompanied by the expansion of the city’s territory, the development of new – urban and suburban – neighborhoods, and profound architectural transformation (fig. 2). Those changes resulted in the emergence of a metropolis composed of a population notably diversified in regard to language, nationality, confession, social strata, wealth, and profession.8 The altered urban landscape, with its new districts, houses of the different trading nations (naties), civic and commercial public buildings (such as the new town hall and exchange and weighing house), visually projected the heterogeneity and unique dynamism of mid-century Antwerp.

All those processes intensified in the 1550s and early 1560s – the period of Bruegel’s artistic activity. One of the by-products of such rapid change was Antwerp’s failure to sustain traditional forms that promoted social bonds among the inhabitants.9 Therefore, at the time when Bruegel painted theTower of Babel, the question posed by the panel was an especially pressing one for the society. In order to maintain prosperity, they needed to find a means of overcoming the inherent differences in the community. Some of the specific mechanisms developed by the city to bring its inhabitants together included the rhetoric of public spectacles, prognostications, emblems, and vernacular poetry, which emphasized the precedence of common welfare over individual gain, making an attempt to define the virtues of ideal entrepreneurs and condemning greed and self-interest. Whereas Ethan Matt Kavaler has argued that Bruegel responded to those concerns by affirming communal responsibility and criticizing unrestrained personal ambition in his secular compositions such as the Fall of Icarus and Elck, I propose that the artist also visually articulated his broad interest in the worth and dangers of commerce in his biblical narratives, the Tower of Babel being one of the most elaborate examples.10

Historical events proved that the developed rhetoric of common welfare had serious shortcomings. A conflict between four trading nations about which would occupy the more prominent position in the procession to welcome Philip Habsburg in 1549 prompted Charles V to ban three of them altogether, while an attempt to monopolize the beer industry by Gilbert van Schoonbeke, an entrepreneur who was connected to Jonghelinck, led to urban riots in 1554.11

The connection between Antwerp’s circumstances and the painting’s iconography, which has been acknowledged by scholars in the past, and which is the premise of this essay, is based on the period understanding of Babel as a metaphor for Antwerp. This connection is further fostered by the social context in which Bruegel’s panel was used – convivial dinner conversations – which offered their participants an opportunity to strengthen communal and professional bonds.12 This, in turn, establishes Bruegel’s painting as a discursive object that played a vital role in the creation of a harmonious community in mid-sixteenth-century Antwerp.

Brabant Landscape, Roman Coliseum: Bruegel’s Vision of the Tower of Babel

Bruegel situated his tower, which looms over a densely populated town, in a vast landscape flanked by a wide, twisting river to the right. The city is cut with canals and enclosed by city walls. It has a narrow agricultural belt, fields, hills, and randomly dispersed buildings beyond the walls. The edifice casts its shadow over a busy river harbor. Across the right side of the tower and toward one of its arches extends a diagonal, which emphasizes the structural connection of the building and the town. Still under construction, the tower is already integrated into the city itself. It has become a new neighborhood, offering permanent dwellings for the population, who have decorated the facade with flowers and, somewhat less decorously, are drying their laundry outside. In Bruegel’s interpretation, the completion of the project is not a condition of its success – and I shall come back to this observation shortly.

Integral to the city, the edifice is being carved from bedrock, which, in its crude form, can still be seen in the lower middle part of the edifice and in its upper right stories. The tower, the ground, and the surrounding territory are therefore deeply interconnected, while the sense of stability introduced by the use of the living rock as a basis is further conveyed by large supporting pillars at the very bottom of the structure. The author of the project, identified by Flavius Josephus in his Jewish Antiquities as the giant Nimrod, is shown on the low hill in the bottom left corner of the composition next to the masons cutting stones for the tower, some of whom genuflect in front of their sovereign.13

Two aspects of Bruegel’s representation of the Old Testament narrative deserve particular attention: the inclusion of several elements that visually resemble Antwerp and his modeling of the shape of the tower after the Coliseum.14 The visual affinity between the biblical site, as depicted by Bruegel, and Antwerp is established first by the setting. The landscape consists of vast flatlands, with a wide twisting river to the right, which extends up to the horizon and evokes the surroundings of the metropolis. Second, the city within which the tower is being erected is clearly a well-developed, large, and densely populated community. The architecture spans the domestic and public, the civic and sacral, and is stylistically typical of late medieval and early modern Brabant. The city is enclosed by walls, with a tall, overpowering gate, which can be associated with Antwerp’s Gate of St. George, with agricultural terrain beyond the fortifications. Finally, the edifice is situated right next to a harbor, which plays an essential role in the depicted community, secures its development, and keeps the inhabitants busy. Most importantly, the tower can only be built thanks to this direct access to the river, allowing for an ease of water trade and transportation of materials.

Visual affinities between Bruegel’s depiction of the Tower of Babel and Antwerp have an equivalent in contemporary texts. In his letter to Philip II dated February 29, 1568, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the third Duke of Alba, described the metropolis as “a Babylon, a confusion and receptacle of all sects indifferently.”15 He complained particularly about its confessional diversity, which resulted in difficulties in implementing edicts defending the Catholic faith against religious dissidents. This attitude was not limited to the Spanish authorities: a Catholic monk, known as Brother Cornelis, similarly indicated that, due to the presence of innumerable foreigners and heretics, Antwerp was transformed into “the great Babylon.”16

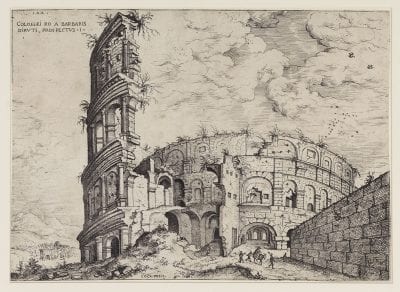

While the topography of the city and its landscape surroundings locate the Tower of Babel in contemporary Brabant, its design takes the viewer to ancient Rome. Bruegel mimics the circular architecture of the Coliseum, with its arched openings and articulation through pilasters, while, as observed by Margaret Carroll, the “concave interior of the imperial amphitheater is rendered in convex projection – turned, as it was, inside out.”17 Bruegel’s choice of model for his tower had far reaching implications for the panel’s use in convivial conversation. The Tower of Babel is a successful and thriving project in progress; the Coliseum, however, in Bruegel’s time was a ruin that was overgrown with weeds. Its dilapidated state was recorded by Hieronymus Cock in one of the prints from his series Roman Ruins(1550) (fig. 3) and in Maarten van Heemskerck’s Self-portrait with Colosseum(1553); both Cock and Heemskerck emphasized that what once was an engineering tour de force and a demonstration of the Romans’ ingenuity in the realm of impressive, utilitarian architecture had become a disillusioning reminder of the passage of time, which would eventually devour everything.

Bruegel therefore confronts his audience with the juxtaposition of a successful construction process and ancient Roman architecture, activating beholders’ knowledge of the biblical story in which the Tower of Babel perished, just like the Coliseum eventually did, and situating those events and stories in contemporary Brabant. This combination of the Old Testament narrative, the painting’s iconography, and invoked background knowledge resulted in complex chronological relationships within the panel. Appropriating the form of the Coliseum, Bruegel created a temporal paradox by visualizing a catastrophe, which has already occurred, but which, at the same time, is yet to happen. Scholars in the past pointed toward different elements foretelling the project’s disaster, such as the instability of the tower’s basis, lack of efficiency in the workers’ activities, and their inability to overcome the forces of nature exemplified by the crude rock formation.18 However, the organic, bedrock foundation of the edifice, as well as the collective effort, with tasks well-divided among the builders, seem to promise the success rather than the failure of the project.

Intended to remain a project in progress, the Tower of Babel has already become an integral part of the city and its inhabited neighborhood. The population can be seen improving their dwellings and building their community, benefitting from each other’s skills and abilities, which renders the architectural allusions to the Coliseum the only indication of possible future catastrophe. The lack of any immediate signs of the disaster preconditions the painting’s use in a convivial conversation on a prosperous community by providing a discursive space within which a positive resolution is possible. Bruegel suspends the biblical narrative: the viewers know that the Tower of Babel has been destroyed, but they approach it in a moment when they can temporarily dismiss the catastrophic ending of the project. Imitating the design of the Flavian Amphitheater and juxtaposing it with the thriving construction, Bruegel visualizes a disaster that can be viewed as both inevitable and preventable by his audience. As we shall see shortly, this temporal paradox is complemented by the further compositional strategies of involving the audience in the conversation about their community. But the question that needs to be addressed first is why such conversation was so crucial at the time when Bruegel painted the Tower of Babel for Jonghelinck.

“The Town Most Frequented by Pernicious People?” The Transformation of an Urban Community and Its Challenges in Mid-sixteenth-Century Antwerp

Mid-sixteenth-century Antwerp can, in many ways, be understood as an extremely successful metropolis. Nevertheless, the city’s rapid demographic, economic, and territorial growth also led to significant challenges for its citizens. The narrative in Genesis 11 accommodates the ambiguity of such a progress: it is a story of human ambition, technological advancement, and collective effort, which led to an audacious project on an unprecedented scale. However, the exact same ambitions that inspired Nimrod and his subjects, and allowed for the construction to go smoothly, eventually caused its disaster: “And he [the Lord] said: Behold, it is one people, and all have one tongue: and they have begun to do this, neither will they leave off from their designs, till they accomplish them in deed. Come ye, therefore, let us go down, and there confound their tongue, that they may not understand one another’s speech. And so the Lord scattered them from that place into all lands, and they ceased to build the city” (Gen. 11:6–8).

God punished their vanity by confusing their languages; as a result, the established community of workers could not communicate either with themselves or with their sovereign, and abandoned the project.19 The miscommunication among the suddenly diversified population of the land of Sennaar forced them to cease the construction of the tower, which otherwise would have been successfully accomplished. The situation of mid-sixteenth-century Antwerp presented a reversed version of this narrative: it was an extraordinarily diversified community, composed of a population that spoke different languages and came from different countries, which needed to become a unified sociopolitical organism with shared economic and political goals. While Babel moved from unity to disintegration, Antwerp was moving from heterogeneity to consensual harmony. In both instances, it was the notion of communication that determined the fate of the cities, which rendered the biblical narrative particularly appropriate for the theme of a painting used in a convivial conversation.

Antwerp’s population reached its peak between 1556 and 1567 with approximately 88,000 to 90,000 permanent citizens and between 10,000 and 12,000 transient inhabitants.20 The main factor that contributed to this increase was immigration both from the Low Countries and abroad. Contemporary witnesses were often amazed by the diversity resulting from this influx of foreigners. Ludovico Guicciardini, a sixteenth-century Florentine merchant, writer, and historian who settled in Antwerp, praised its cosmopolitan atmosphere, “great coming together of so many people and nations,” and “new tidings from all over the world,” and clearly enjoyed the fact that one can “learn customs and manners of many different nations in one city, without travelling far.”21 However, not everyone in the period shared Guicciardini’s enthusiasm – in the already quoted letter to Philip II, the Duke of Alba characterized Antwerp as “the town most frequented by pernicious people.”22 Its central position in maritime trade and its role as a “permanent international entrepôt”23 was potentially dangerous as it allowed for a prompt dissemination of ideas in the age of the Reformation. Habsburg concerns were justified: a broad and efficient mercantile network, with Antwerp at its center, facilitated the exchange of not only commercial goods but also religious writings, and Protestant preachers often came to Brabant in merchants’ disguise. On the other hand, the metropolis flourished precisely because it brought together entrepreneurs from all over Europe, and the Spanish administration could have hardly denied the concomitant benefits. Indeed, the example of Antwerp proved one economy-oriented exegesis on Genesis 11 wrong: in his sermon, Martin Luther stated that “where the languages differ, . . . no commerce develops.”24 But Antwerp in general, and places such as the New Exchange in particular, functioned as an anti-Babel. According to Guicciardini, this necessity to conduct international business relations resulted, in turn, in the extraordinary language proficiency of Antwerp’s citizens, who often spoke three, four, or even more languages.25

The presence of naties further led to the architectural transformation of the city. In the sixteenth century, Antwerp was quite literally built by people speaking different languages, who founded national trading houses with ascribed social, mercantile, and storage functions. Designed in distinct architectural styles that followed the fashion immigrants knew from their countries of origin, new buildings projected both the heterogeneity and the unifying potential of Antwerp. Composed of such a diversified group, the city helped to overcome boundaries, hostilities, and prejudices within it by providing foreign entrepreneurs with unique financial opportunities. They, on the other hand, contributed to the commercial and intellectual development of the metropolis.

This interdependence of trading nations and Antwerp was confirmed and praised in ephemeral decorations constructed for the joyous entry of Crown Prince Philip, son of Charles V, in 1549.26 The naties used Philip’s entry to visually articulate their prominent roles in the city’s economy and culture, and the metropolis, in turn, confirmed such aspirations. The iconography of Spanish, Florentine, and Genoese triumphal arches underlined their contribution to Antwerp’s prosperity and found its counterpart in the tableau vivant staged by the city and dedicated to the theme of trade (fig. 4). Here, the personifications of Antwerp and Negotiation, together with Mercury and the god Scaldis, supplemented allegorical representations of German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and English trading nations (fig. 5).27

For Guicciardini, the 1549 entry was one of the three most important events in contemporary Antwerp; not only was it an extremely lavish (and expensive) spectacle, but it also brought the community together.28 However, this optimistic rhetoric of common welfare was not unblemished. One part of the joyous entry was a horseback procession in which representatives of all trading nations partook. City officials opened the procession and were followed by the naties; according to contemporary custom, groups that rode further behind were regarded as more prestigious. Not surprisingly, each wanted to secure the most prominent position and sent in advance appropriate requests to the organizers of the festivities.29 Needless to say, the latter could not satisfy all of the demands they received; the situation got particularly tense among Portuguese, English, Florentine, and Genoese merchants. Since city officials could not solve the conflict, they eventually turned for help to the emperor, who banned three of the four naties – Portuguese, Genoese, and Florentine – from the procession altogether, sparing only the English colony30 The incident thus showed very clearly that putting particular national interests first, before the well-being of the entire community, ultimately worked to the disadvantage of its individual members.

Bruegel’s panel offers a similar praise of collective efforts, contributing to the ubiquitous contemporary narrative, which defined the prerequisites of a welfare enjoyed by all social groups. His other compositions, such as the drawing of Elck, participated in a complementary discourse by codifying the virtues (and warning against the vices) of an entrepreneur: honesty, self-restraint, and self-knowledge.31 Similarly, according to rhetoricians, a “paragon of mercantile virtue” was a fair and just merchant who despised dishonest financial speculation but lent money to those in need and supported charitable foundations. The same point was repeatedly made in annual prognostications, which predicted peace, solidarity, and prosperity for the urban population and promised it to merchants in particular – but only to those merchants who remained “pious” and based their transactions on Christian values.32

An example of an entrepreneur who lets us better understand the relationship between this postulated model and actual business practice, and how the community assessed and reconciled discrepancy between them is Gilbert van Schoonbeke (1519–1556), a land speculator who virtually monopolized the real estate sector and public works in Antwerp during the 1540s and 1550s.33 It was he who created the Leikwartier south of the city walls – the district that became the location for Jonghelinck’s villa.34 Collectively, his initiatives rapidly transformed the urban space and defined it for the next four-hundred and fifty years: he started the construction of a new Stadswaag (weighing house) and Vrijdagmarkt (market square); initiated the planning of the Tapissierspand (a marketplace specifically designed and used for the tapestry trade); was put in charge of completing city walls and fortifications; and finally, developed the Nieuwstadt, a new district that was incorporated into the city in 1542. Around those new commercial centers Van Schoonbeke created individual parcels that were sought after by merchants who appreciated the convenience of proximity to the mercantile buildings. They instantaneously became an integral part of Antwerp, just as in Bruegel’s panel the Tower immediately became a new neighborhood inhabited by the city’s population.

Van Schoonbeke’s career was unprecedented: without any family inheritance, he became one of the wealthiest and most influential citizens of Antwerp. But, as his contemporaries did not fail to point out, his fortune was not merely the result of luck and smart business moves. In their official complaints, Van Schoonbeke’s adversaries accused him of speculating on the communal grounds he was administering without handing over the revenue owed to the city’s treasury and of inflating the prices of sold parcels.35 These accusations of financial transgressions and corruption did not spare the city magistrates either, who supposedly gave Van Schoonbeke priority over other entrepreneurs. Van Schoonbeke was well aware of this resentment –in 1548 he wrote in his letter to Governess Mary of Hungary that many people were working to his disadvantage.36

Van Schoonbeke strove to meet the standards of an exemplary merchant established by the rhetoric of public spectacles by supporting the community with charitable foundations.37 Nevertheless, the hostility against him persisted. Its climax came in 1554, when the entrepreneur and the city council agreed on starting a series of breweries in the Nieuwstadt, while simultaneously banning the import of beer from other cities. This decision, which was obviously damaging to middle-class merchants, led to open riots and protests. Van Schoonbeke and the city council were eventually forced to break the contract and to relocate the excise offices. To prevent similar troubles in the future, in 1555 Charles V enforced an edict that prohibited monopolization both in trade and artisanal production as damaging to the entire community.38 Despite those measures, unrest and minor rioting lasted for several months.39 Guicciardini’s account of this event emphasizes that the conflict involved all three parties, which collectively constituted the ghemeynte (community): Heeren van der Stadt (city council), ghemeynen volcke (common folk), and borghers (citizens), and that it was damaging to all of them.40 But when peace was eventually restored, it was thanks not to the government but to the vrome borghers – pious citizens – who took charge of specific districts of Antwerp and prevented bloodshed.

The subject matter of Bruegel’s Tower of Babel – the construction of an edifice and a city on an unprecedented scale – and the question it asked viewers – how to create and maintain a prosperous and harmonious community – resonated with the commercial and urban development of Antwerp in the period and, consequently, the controversial activities of Van Schoonbeke. The 1554 unrest proved that these activities led to disorder and created distrust within the community, divided citizens, and turned them against each other. I do not want to suggest that Bruegel’s primary audience explicitly identified Nimrod with Van Schoonbeke; however, the panel does evoke the issue of individual versus collective effort in executing an ambitious and laborious project. It privileges the collaboration of the workers; Nimrod initiated the construction, but it was thanks to the harmonious collaboration of his subjects that the Tower of Babel was being built. The king could not afford to turn the population of his state against him, and when he eventually could not communicate with them anymore, the construction met its catastrophic ending. The painting served as a reminder that the model of entrepreneurship adopted by Van Schoonbeke was an ambivalent one and could have potentially led to the destruction of an otherwise prosperous community.

Hence, Bruegel directed his viewers toward one possible solution: in order to maintain social order and a thriving commerce that would secure the well-being of all the citizens, it was necessary to support the joint endeavors of the entire population, as well as to recognize and make the best use of their respective specialized skills and knowledge rather than focus on one’s own interest. The diversity of the Antwerp population in regard to educational backgrounds, professional experiences, language proficiencies, and international contacts would remain profitable for everyone, and secure harmony and progress, as long as the welfare of the entire community was recognized as having priority over an individual’s own private gain. This argument was made repeatedly in contemporary ephemeral culture, and we saw earlier how Emperor Charles V taught a similar lesson to the quarreling trading nations by eventually banning three of them from the procession for Crown Prince Philip in 1549.41 While in those instances the message was presented to the entire community gathered to witness a public spectacle, Bruegel’s painting stimulated such reflection within the semiprivate domestic setting of Jonghelinck’s suburban villa.

Spatial and Intellectual Frameworks of the Reception of Bruegel’s Tower of Babel

Conversations about the local community facilitated by the Tower of Babel happened in the discursive space created by the temporal paradox introduced by Bruegel. The painter employed further strategies to engage his audience visually and intellectually, thus encouraging them to become part of the depicted narrative and to partake in a convivial dialogue. Such an invitation to enter the pictorial space was a common technique of Bruegel, in which he relied on earlier Netherlandish tradition and viewers’ awareness of the strategies of visual persuasion.42 The ultimate effect was the conflation of the real space of a viewer with the pictorial space, achieved by establishing both a compositional and a conceptual relationship between the two. Todd Richardson has shown how in the Peasant Wedding Banquet, Bruegel organized the composition so that a beholder becomes a guest of the party, for whom an empty chair and plates are prepared. Since the image was most likely used in convivium, accepting this invitation resulted in establishing a parallel between the event shown in the painting and the feasts for which it served as a backdrop.43

Such a connection holds true as well for the primary theme of the Tower of Babel – the building of the edifice – and the panel’s function. In its lower left corner, Bruegel situated two workers carving stones for the tower, while another block of stone has been abandoned by a laborer, who is kneeling in front of Nimrod. On top of that stone, whose corner protrudes into the viewer’s space, the builder has left his hammer and three chisels, which are similar to those being used by his colleagues. The hammer is turned toward the viewers and arranged on the extension of a diagonal created by the genuflecting workers, further drawing their attention to this detail. Bruegel invites the beholders to pick up the tools and participate in the building process, which can be understood on two levels. First, Bruegel’s tower is supposed to remain a project in progress: the population needs to keep working on creating their community in a collaborative effort. By comparing Babel to Antwerp, Bruegel encourages his audience to further advance the metropolis’s development. However, the necessary condition of the economic and cultural progress was the unity of its citizens, which was achieved through, among other means, convivial conversations. Hence, the tools placed by Bruegel on the limestone function metaphorically as a first gesture toward a learned conversation. The same limestone is also where Bruegel decided to sign and date the panel. The lettering and placement of the signature was yet another rhetorical strategy eagerly employed by the artist to make a theoretical statement: for example, in the Netherlandish Proverbs and Children Games the artist’s signature serves as an assertion of artistic modesty.44 In the Tower of Babel, the signature, “BRUEGEL. FE. M. CCCCC. LXIII,” imitates carving in stone. Its location and the chosen script require us to read it in conjunction with the hammer and chisels. Having invited his audience to take part in the building process, at the same time he situates himself on the construction site, among the craftsmen. If viewers are encouraged to carry on the process of building their metropolis, and of building a community through convivial conversations, then Bruegel presents himself as someone who participates in both of these processes. He is one of the most celebrated and distinguished painters in a city known for its flourishing art market, and thus contributes to its prosperity and fame; at the same time, he is the author of deliberately discursive, open-ended, and even ambiguous compositions,45 which are meant to encourage the local elite to collaboratively participate in self-reflection and self-examination.46

The self-examination facilitated by the Tower of Babel took place in the semipublic domestic space of Niclaes Jonghelinck’s suburban villa. Jonghelinck bought the residence ‘t Goed ter Beke from his older brother, Thomas, in 1554.47 Jonghelinck belonged to the financial and social elite of the city, and members of his family held prestigious offices and were connected to both the local and the central government. Niclaes’s father, Pieter, was a medalist and the Mint Master of Brabant; this office was assumed in 1560 by Pieter’s oldest son, Thomas, and in 1572 by his youngest son, Jacques. Niclaes’s own career was no less impressive than that of his brothers: in 1551 he was appointed collector of taxes in Zeeland and Brabant.48 In the 1560s, he often speculated on city lotteries, using his art collection and urban house, Sphera Mundi, in Kipdorp as collateral. Since those risky ventures resulted in significant debts, after Niclaes’s death in 1570 several of his paintings came into the hands of Philip II, one of Jonghelinck’s most important creditors.

Niclaes was directly connected to the contemporary art world through his brother Jacques (1530–1606). In addition to his appointment at the Brabant Mint, Jacques was a sculptor, medalist, and designer of seals. After training with his father, and later possibly with Cornelis Floris, he left for Milan to work with Leone Leoni until the early 1550s.49 Just as Niclaes was connected both to the local and central administrations, so did Jacques work for Governess Margaret of Parma, Philip II, Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, the bishop of Arras, and Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the third Duke of Alba,50 as well as the Antwerp mayor Antoon van Stralen and private commissioners, including Pieter Bruegel’s friend Hans Franckaert51 and Niclaes himself.52 After Niclaes’s death in June 1570, Jacques was appointed the executor of his will, together with Jacques van Hencxthoven, who in the 1560s had partnered with Niclaes in organizing lotteries53 and in 1570 was warden of the Antwerp Mint.54

While Van Hencxthoven was identified as a spice merchant in documents from 1543, he later became involved in local military affairs and acted as the king’s advisor on the matter of supplying the Spanish troops stationed in the Low Countries. In addition, he was responsible for the construction of the Citadel (1567) and new fortifications (1569) in the city.55 Van Hencxthoven also provides a connection between Niclaes Jonghelinck and Gilbert van Schoonbeke: as suggested by Smolderen, Van Hencxthoven participated in some of Van Schoonbeke’s ventures in the 1550s.56 The broad scope of Van Hencxthoven’s business undertakings allowed him to gather a large fortune, which he partly spent on a collection of paintings and on the purchase of a residence in Hemiksem, a small community south of Antwerp.57 His career thus resembles that of Niclaes and there can be little doubt that Van Hencxthoven was one of the guests at Ter Beke.

As the warden of the Antwerp Mint, Van Hencxthoven was responsible for overseeing its master, Jan Noirot, who, in turn, might have been introduced to Bruegel by Niclaes Jonghelinck.58 In all likelihood, Noirot was, therefore, yet another member of the local elite who dined at Ter Beke. In the late 1560s, he commissioned from Bruegel five paintings with peasant subjects, four of which were displayed in his dining room.59 Finally, Niclaes’s position among the local elite was strengthened by his first marriage to Anna de Colenaere, daughter of the former city recorder, Jean de Colenaere.60 As all of his professional, personal, and family connections indicate, the guests whom he entertained at Ter Beke belonged to the financial, mercantile, and cultural elite of the period. By purchasing a suburban villa and displaying an extensive painting collection in its interior, Niclaes projected an image of himself as a wealthy, knowledgeable, and sophisticated citizen concerned with the well-being of the community to which he belonged and that he served. Visitors such as Noirot, Van Hencxthoven, and his brother Jacques, vitally interested in the welfare of Antwerp themselves, would have undoubtedly understood that message. The 1565 inventory of his possessions confirms Jonghelinck’s interest in art produced in contemporary Antwerp and his attempt to create a comprehensive collection that both featured the works of the best painters of the period, including Frans Floris and Pieter Bruegel, and encompassed diverse subject matters and genres. In their respective ways, the works of both Floris and Bruegel allude to life in sixteenth-century Antwerp: Bruegel’s Months relate to local agriculture, while the depiction of Mars Disarmed by Four Virtues in Floris’s Awakening of the Arts evoked the devotional procession on the Feast of Circumcision in Antwerp in 1559.61 Jonghelinck’s civic virtues and profound preoccupation with the local community were thus explicitly demonstrated by the specific choices he made in regard to the profile of his collection. In turn, those who viewed them were conditioned to search for affinities between the paintings and their metropolis. The collection as a whole established a mode of actively looking at images and interpreting them in the local context. The specific spatial and conceptual frameworks of the reception of Bruegel’s Tower of Babel thus reinforced affinities between the depicted subject and Antwerp that were inherent in the painting’s composition and encouraged by period discourses.

The custom of convivia and the Italian ideal of country life (villeggiatura), which in the mid-sixteenth century found its way to Northern Europe, further contextualized the reception of Bruegel’s painting. Suburban villas provided the perfect setting for a sophisticated yet friendly conversation and allowed discussion of topics that elsewhere might be improper. Guests were encouraged to speak freely and yet they did not trespass against any of the norms of a cultured conversation. This resonated with the diversity of convivial talks promoted by both ancient and early modern authors, who believed that the very exchange of arguments was more important than achieving a consensus, and that a one-dimensional discussion, in which everyone agrees, should be avoided.62

In the sixteenth-century Netherlands it was Erasmus’s Convivium Religiosum (The Godly Feast) that most explicitly emphasized the link between convivium and villeggiatura, underlining their shared purpose of moral edification. In Erasmus’s telling, Eusebius invited eight of his friends to his country estate for a luncheon; the meal was preceded and followed by a tour of the garden and the house. Erasmus thus set the stage for a colloquium characterized by an informal and yet profoundly spiritual atmosphere. Essential for both the setting and the subject matter of conversation are the paintings displayed on the walls of Eusebius’s residence. The interior of the summer dining hall is decorated with images of the Last Supper, Herod’s Feast, the Rich Man and Lazarus, Antony and Cleopatra, Alexander the Great Killing Clitus, and the Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs.63 The themes of the paintings resonate with the function of the room: the first one provides the ultimate example of a meal that should be remembered and imitated by all Christians, while the remaining biblical and classical stories of famous feasts warn against the consequences of drunkenness and gluttony. In prescriptive terms, the paintings are intended to spark a morally edifying and profitable conversation among the dinner party guests. They perform the exact same role as convivium itself: as Eusebius explained to Timotheus, “this custom, it seems to me, has much to recommend it, because by means of it one can avoid foolish yarns and enjoy profitable conversation. I disagree emphatically with those who think a dinner party isn’t enjoyable unless it overflows with silly, bawdy stories and rings with dirty songs.”64

The convivial framework established by Erasmus and the inclusion of images in the dialogue shed light on how the collection of Niclaes Jonghelinck at Ter Beke functioned. The Godly Feast supports the idea that it was not only the paintings but also their use as the locus of a learned conversation that established the owner as a knowledgeable and virtuous citizen. In accordance with their edifying function, the dinner parties offered an opportunity to sustain communal bonds.65 Likewise, the images’ status as discursive objects that required an engaged group response was crucial in their importance for the community. However, as Erasmus and other authors of convivial treatises explained, that response did not have to be uniform to maintain the atmosphere of a friendly dialogue, “which was equally learned and devout.”66 Therefore, while in the story of the Tower of Babel, miscommunication and a confusion of different voices led to the destruction of a community, in convivium an ostensibly confusing diversity of opinions expressed by interlocutors was highly desirable and created an opportunity for communication with an advantageous outcome.

Understanding Erasmus’s Godly Feast as a model for Jonghelinck’s dinner parties is further supported by the fact that the colloquium was inspired by convivia attended by the humanist in Mechelen at the house of Jeroen van Busleyden, the founder of the Collegium Trilingue at the Catholic University in Leuven.67 The scholars belonging to Busleyden’s social circle recognized the images decorating the interior of the residence as an integral part of their discussions and as a crucial factor in creating a decorous setting for debates. In addition to Erasmus, Thomas More was among those scholars; thus, the mealtime gatherings at Hof van Busleyden promoted the development of an international humanist network.68 Half a century later in Antwerp, the custom was appropriated by less erudite entrepreneurs, who nevertheless cultivated it as a means of strengthening international and local commercial bonds, and for the sake of the improvement of the self and of the community. The correspondence of Antwerp officials provides ample evidence of the significance of meal gatherings for the social, religious, economic, and political life of the metropolis. For instance, in February 1566, the city’s pensionary, Jan Gillis, describes, in a letter addressed to the mayor, Lancelot van Ursel, a dinner party he had attended a few days earlier at the house of one of the secretaries, during which, in the company of other officials and their wives, he discussed requests from Brabant towns for help with the new laws implemented by the Inquisition, merchants’ complaints about a recently published edict that caused them significant financial troubles, and the forthcoming meeting of the city council regarding that ordinance. Van Ursel apologizes for not having responded in time to a letter by Gillis of a few weeks earlier, as he has been busy attending several wedding feasts. He reminds Gillis that they need to discuss the implementation of the edicts of the Council of Trent and also promises to tell his colleague about a banquet with the Prince of Orange, but only when they meet in person, as those matters should not be written down on paper.69

The Tower of Babel Redeemed?

The specific location of the villa in which Jonghelinck and his guests conversed about matters such as urban, demographic, and mercantile transformation – the Leikwartier created by Gilbert van Schoonbeke – helped to further nuance their discussions. One of the crucial issues they had to confront, the relationship between private profit and collective prosperity, was epitomized by the ventures of Van Schoonbeke. The controversial entrepreneur contributed to the territorial expansion of Antwerp and its profound architectural transformation, but he also antagonized the citizens of the metropolis. His ambiguous example admonished merchants and officials about the virtues of moderation and reminded them that the welfare of the community should take precedence over self-interest. This focus on the common good justified the period’s pursuit of wealth, while greed and unrestrained ambition remained a threat to the stability of the society.

This message echoes the moral of contemporary prognostications, poetry, emblems, and vernacular plays, as well as of Bruegel’s secular compositions from the 1550s and 1560s.70 Its appropriation for convivia at Ter Beke was reinforced by the profile of the entire collection displayed in the villa, which conditioned its audience to relate the iconography of images to their metropolis. Consequently, a learned dinner conversation offered them an opportunity to develop the model of ideal entrepreneurship, just as half a century earlier it had fostered development of humanist networks and fulfilled intellectual ideals. The ultimate answer to the problem posed by the Tower of Babel – how to create a harmonious and prosperous community founded upon Christian and humanistic values – was provided by the very use of the panel in a convivial conversation. Its function as a stimulus for a unifying intellectual exchange reverses the biblical narrative on the disastrous effects of the lack of communication. Nevertheless, it also perpetually reminds the participants of those conversations about the threat of a potential catastrophe if they fail in their responsibilities to their collective project, the international metropolis of Antwerp. The redemption of Bruegel’s Babel is conditional and unsecured, as was the fate of the city in the period when Jonghelinck commissioned the painting for his suburban residence.