The goal for this project was to create an interactive digital presentation on the evolution of Peter Paul Rubens’s The Fall of Phaeton by modeling the use of technical study in an art historical context.

With this purpose in mind, Melanie Gifford and I began to consider the primary audiences for the project. While JHNA has an established user/reader community, the project offered opportunities for expansion. The audiences would encompass art historians and conservation scientists interested in exploring the content in depth as well as a potentially broader audience of undergraduates, graduate students, and others seeking to understand research methodologies in the field of technical art history. As the Digital Humanities Developer contracted for this project (with important support from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation), I worked with Melanie to determine a conceptual framework. After some discussion, we decided that there were two challenges to sharing this research:

- presenting the material in a user-friendly and efficient way, one that would allow readers fluid access to the text and the relevant images as they scrolled, and

- creating a “sandbox” for readers to explore the technical evidence independently; see Exploration and Resources.

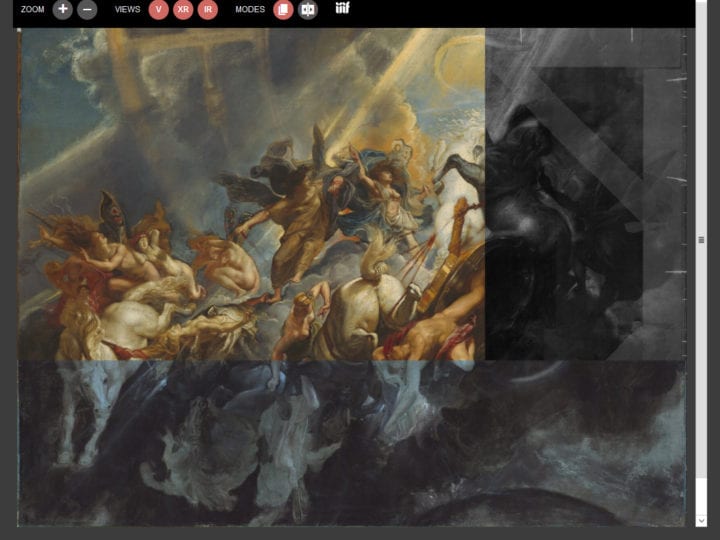

The “sandbox” has taken the form of enhanced image offerings using the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF, or “triple eye eff”). IIIF was founded with the goals of providing depth of access using application programming interfaces (APIs) that allow for better navigation between the various image viewing platforms through which museums, universities, and other cultural institutions share their images. At the same time, it maintains important object metadata across these viewers — as well as offers the user opportunities to compare, zoom, and explore images in unprecedented ways. For our purposes, the OpenSeaDragon viewer, an open-source tool modified and customized by Cuberis (a design and technical development firm devoted to museums) that works well with the WordPress content management system used by JHNA, offered the greatest gains with easy content management system (CMS) integration.

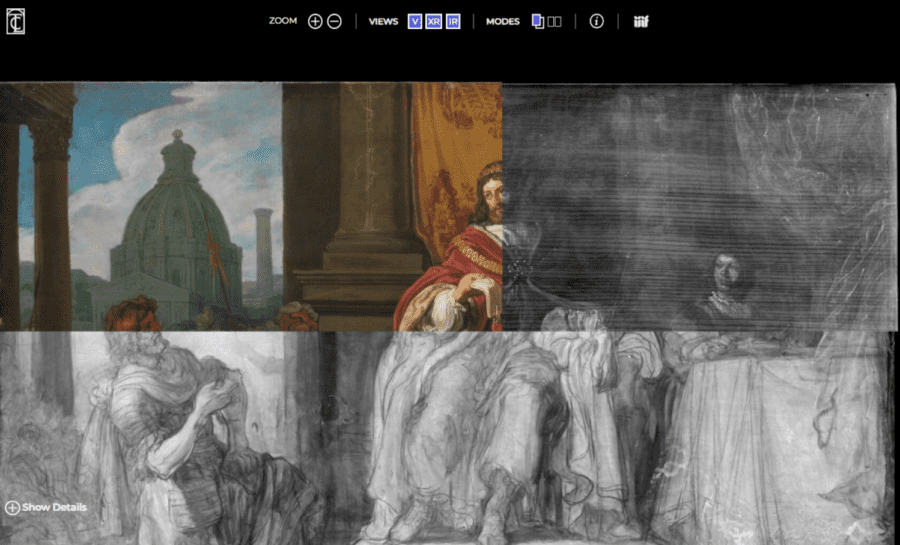

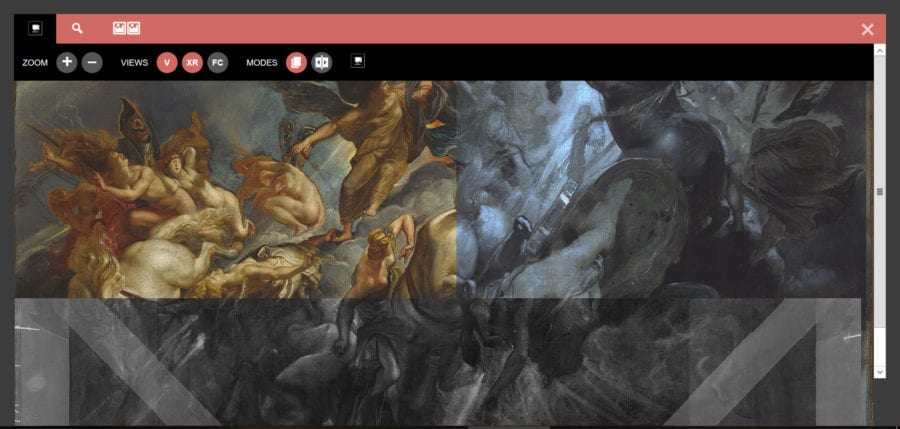

The viewer being used by JHNA is indebted to several precedents, most directly the viewer employed by the forward-thinking Leiden Collection, and also to the innovative “curtain” viewer first designed by scientist Robert Erdmann. The “curtain” viewer was first unveiled for the Bosch Research and Conservation Project in 2014 to integrate visible light imagery with technical images (such as X-radiographs and infrared reflectograms) in an interactive simultaneous viewing mode, in contrast to the static side-by-side comparison that is customary in art historical contexts. The curtain viewer synchronized zooming across several “stitched” images, enabling the viewer to mobilize the view with the movement of a mouse or touchpad cursor.1 The Leiden Collection engaged Erdmann to modify his curtain viewer for their online scholarly catalogue, which launched in 2017. Subsequently, The Leiden Collection opted to convert all images to IIIF compatibility and enhanced selected objects with a IIIF-compatible “curtain/sync” viewer in OpenSeaDragon akin to the Erdmann-created display (see, for example, Pieter Lastman’s David Gives Uriah a Letter for Joab).

The enhanced viewer allows users to explore pentimenti, changes in the support, and so forth across a single image. The viewer also offers a sync option, which displays registered images that allow for concurrent zooming to the same point across multiple images. Creating these images in IIIF, the OpenSeaDragon viewer now provides the images with the same behavior.

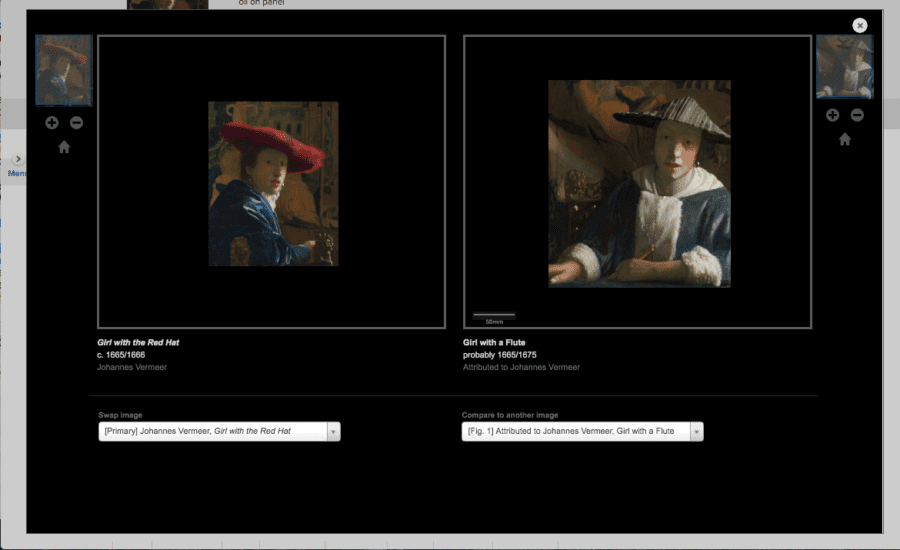

Thanks to the generosity of the Cuberis team and The Leiden Collection, the OpenSeaDragon viewer code is available for use and customization via GitHub. This code served as the basis for the JHNA team (managing editor Heidi Eyestone, programmer Morgan Schwartz, and myself) to develop it for JHNA while adding some enhancements. The curtain/sync viewer offers a deep look into a singular image set. But an image-compare tool, one that permits the comparison of two images side-by-side in the traditional art historical approach, was a vitally desirable feature for this project. The National Gallery of Art Online Editions’ Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century, for example, employs a modal compare window for the comparative figures in an object entry (for example as an object on view here).

It also appears with zoom and pan controls, as well as a dropdown menu for other comparative figures mentioned in the text. Our team sought to merge the viewers used by The Leiden Collection and the National Gallery of Art into an enhanced image viewer for JHNA by combining the benefits of deep zoom / overlay options with IIIF for a singular image with the ease of comparing images that are solely drawn together by the author’s text.

Thanks to an additional grant from the Association for Research Institutes in Art History (ARIAH), our team has been able to further enhance these tools by adding pre-set zoom controls to the images in the article, as well as the author’s annotations to pair narrative points alongside the images in an interactive environment. Clicking on a figure showing a detail of The Fall of Phaeton will open the high-resolution overall image at that location. Similarly, when clicking on many figures, readers will find annotations highlighting features of the images. This technology has also been used in the interactive timeline: in addition to plotting the complex relationships between many of Rubens’s works, annotations pull up visual evidence of the relationships.

One particularly challenging element with the implementation of this project has been IIIF image storage. Most IIIF images are extremely large files hosted by the object’s home institution. As online journal publications are not typically in the business of hosting images for indefinite use on their servers, the immediate solution was to host the large image files through IIIF Hosting, which requires a monthly subscription. However, through the largess of our colleagues at the University of Heidelberg, we are delighted to host our images for the foreseeable future on heidICON, the university’s IIIF server, home to a trove of IIIF-compatible images. Solving this issue has not been easy nor straightforward, but utilizing other IIIF hosting services until such a time as all art historical images are hosted and in IIIF compliance puts JHNA on a pioneering path for other online scholarly journals. Hopefully, when more institutions offer their images as IIIF-compatible, server space will no longer be the burden of the publisher and will revert back to the home institution.

The final version of the JHNA image viewer is a forward-looking hybrid model, offering IIIF imagery of The Fall of Phaeton, an enlarged view of the selected image, and finally, side-by-side image comparison, with the option to toggle between other images called out in the text. The modal window sits on top of the text, so when user/readers finish exploring the image, they can close out the window to return to the text with ease.

Additionally, this project features section navigation in the right sidebar, which allows the reader to jump between different sections of the text without scrolling and searching.

The hope is that this offers an improved linear reading experience, and that the nonlinear image exploration is seamlessly integrated with the text of this featured article and those to come; with past JHNA editions; and with the site as a whole. While we already have ideas for the next viewer enhancements, we are delighted to share our progress in this first digital art history publication. It is our hope that this effort contributes to the digital art historical community and other online scholarly journals seeking to engage researchers in new and innovative ways by forging new pathways to explore text and object.