This essay identifies one of Jan van Scorel’s most important, lost works—the Crucifixion for the high altar of the Oude Kerk, Amsterdam—by evaluating the evidence provided by workshop replicas, later copies, and other works influenced by the original painting. The questions surrounding the prestigious Oude Kerk commission play out in the context of Scorel’s reestablishment in the northern Netherlands after his return from Italy in 1524 and the responses by Scorel’s contemporaries such as Maarten van Heemskerck to his new Italianate style.

Jan van Scorel’s Crucifixion for the high altar of the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam is one of the paintings that Karel van Mander lamented was lost during the Iconoclasm in 1566, along with others in Utrecht, Gouda, and elsewhere.1 The sense of loss is made all the more palpable when one considers how the Oude Kerk painting was appreciated by those who had the chance to see it before it was destroyed. In 1549, Juan Cristóbal Calvete de Estrella saw the Crucifixion when he accompanied Philip II on his introductory tour of the Netherlands and described it as the “finest painting in all of the regions of Flanders.”2 Researchers have naturally attempted to identify this famous work on the basis of presumed copies, but to date the scholarship has been inconclusive. Suffice it to say that, on the topic of Scorel’s Crucifixion for the Oude Kerk, there are more unresolved questions than answers.

In 2018, a publication appeared celebrating the Oude Kerk. The entire issue of the Jaarboek van het Genootschap Amstelodamum was devoted to the church and its furnishings. Sebastiaan Dudok van Heel, a loyal author for the journal for fifty years, contributed a substantial article on the high altar by Jan van Scorel and Maarten van Heemskerck.3 In his essay, Dudok van Heel puts forward a number of completely new proposals. They are enumerated here in brief. The first and perhaps most surprising claim is that Scorel completed the altarpiece for the Oude Kerk almost immediately after his return from Italy in 1524. This has never been proposed before, and it contradicts the account by Karel van Mander, who stated that Scorel painted the Crucifixion for the Oude Kerk several years later, after the painter was firmly reestablished in his native land. In order to support his contention, Dudok van Heel speculates that Scorel painted the altarpiece in Amsterdam—not Utrecht, where it is generally assumed the painter settled after arriving back in the Netherlands—and, more specifically, in the workshop of Jacob Cornelisz or that of his son, where, according to Dudok van Heel, Scorel had returned to find lodging and a place to work. Dudok van Heel believes that the altarpiece Scorel delivered to the Oude Kerk was a triptych, not the single panel that is implied in early sources, and that it would have had a lobed top, because that was a common shape seen in altarpieces produced by Jacob Cornelisz’s shop at the time. Furthermore, Dudok van Heel argues the altarpiece eventually evolved into a six-winged polyptych, because Maarten van Heemskerck was commissioned in 1537 to add four wings to the presumed triptych. The wings were presumably intended to cover up the figures of Adam and Eve that Scorel had painted on the exterior of his triptych, since they conjured up uncomfortable memories of the riots of 1535 when Anabaptists ran naked in the streets of Amsterdam. In Dudok van Heel’s opinion, Van Mander was not only mistaken about the date and other aspects of the Oude Kerk commission; he was also misinformed about details related to the painters involved, due to the fact that he had to rely on informants who were too far removed from the time the altarpiece existed. Jan van Scorel, Dudok van Heel argues, did not paint the Oude Kerk Crucifixion during his stay in Haarlem from 1527 to 1530, as Van Mander stated. Nor did Scorel establish a workshop in that city, contrary to Van Mander’s account that, when there, Scorel was “often asked to take in pupils.”4 Maarten van Heemskerck, as a result, could not have joined Scorel’s workshop in Haarlem, even though that report by Van Mander has since been universally accepted in the literature. Heemskerck, Dudok van Heel contends, only learned of Scorel’s new Italianate style through the works that Scorel left behind when he returned to Utrecht. Clearly, Dudok van Heel’s suggestions significantly alter the chronology and activity of Jan van Scorel’s first years back in his native land.

These proposals are challenging and call for a response. The rejoinder the authors present here is offered in the spirit of collegial debate that we hope will lead to more plausible solutions to longstanding, intractable problems. In addition, the authors hope to draw attention to a larger issue: the critical importance of Jan van Scorel’s once-renowned but now-lost works and the immediate impact they had on his contemporaries—not only his followers but also painters of his own generation—in the artistic centers of Amsterdam and Haarlem.

Did Jan van Scorel return to Amsterdam or Utrecht?

When Jan van Scorel resettled in the Netherlands in the summer of 1524, he faced some practical problems. According to Dudok van Heel, the painter was “flat broke” and had no roof over his head.5 The income from a promised church office was not yet available to him, and because he was not a poorter (citizen) in Utrecht or any other Dutch city, he had no way to set up shop and earn a living as a member of a local painters’ guild.6 It was only logical for him to return to Jacob Cornelisz’s workshop and pick up where he had left off six years earlier. From 1512 to around 1518, Scorel had been an assistant in Jacob’s Amsterdam workshop, and during that time he must have been close to Jacob’s two painter sons, who were almost his same age: Cornelis Buys IV (Cornelis Jacobsz), born around 1490–95 (d. 1532), and Dirck Jacobsz, born before 1497 (d. 1567). To Dudok van Heel, the proof that Scorel was painting again in Amsterdam alongside his former coworkers is the immense impact Scorel had on the work of these two members of Jacob’s shop in the second half of the 1520s.7

There is no question that Scorel’s influence on both painters was immediate and transformative. They both began to paint landscapes with antique ruins. Buys IV assimilated Scorel’s figural style, while Dirck Jacobsz exhibited his indebtedness to Scorel primarily in his portraits and more fluid painting technique. The reason we now know that Scorel’s example was much more pervasive than formerly thought is due in large part to Dudok van Heel’s own ingenious research. In 2011, Dudok van Heel published the genealogy of Cornelis Buys, which includes the painter Jacob Cornelisz. His research led to the recognition that the painter known in art-historical literature as Cornelis Buys II is in actuality Jacob Cornelisz’s son—designated as Cornelis Buys IV.8 Needless to say, this shift of an entire painter’s oeuvre from Alkmaar, where it is thought Buys II worked, to Jacob’s family workshops makes the family even more of a powerhouse in early sixteenth-century Amsterdam.

This discovery allowed one of the present authors, Molly Faries, to show how a Jacob Cornelisz shop composition, a Holy Family in a landscape (that is, the Flight into Egypt) was “modernized” on the basis of a now-lost prototype by Jan van Scorel that depicted the same subject. The makeover appears in two same-size shop replicas, one a work by Cornelis Buys IV (fig. 1) and the other a work that can be attributed to Dirck Jacobsz (fig. 2), the middle panel of a triptych with the date 1526 on the middle panel and 1530 on the wings.9 The changes are not obvious at first glance, since the composition is so clearly north Netherlandish, yet they reshape the image. Gone are the heavy brocades, and in their place the thinner fabrics of the Madonna’s dress and robe cling more closely to the body. Mary’s hands are more elegant, with long, tapering fingers. Her coiffeur is completely new and Raphaelesque, with a braid woven around her head. Her knees push forward into the viewer’s space, and her gaze connects with ours. Perhaps most telling of all is the background landscape, a panoramic view with antique ruins, a hallmark of Scorel’s work after his return from Italy. Jan van Scorel’s original must have been a work of high repute, for it also had influence beyond Jacob Cornelisz’s workshop. It clearly provides the Madonna type and basic components of not only Maarten van Heemskerck’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; c. 1530),10 but also Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen’s Holy Family in the Rijksmuseum, dated c. 1528–30.11 In another venue, Faries identifies Jan van Scorel’s lost prototype as the wings for the high altar of the Mariakerk in Utrecht, which the artist must have begun before he left for Haarlem in the spring of 1527.12

This clear link between Scorel and Jacob Cornelisz’s sons prompted Dudok van Heel to speculate that Jan van Scorel found lodging in either Jacob Cornelisz’s house on the Kalverstraat or possibly in the adjoining house belonging to his son, Cornelis Buys IV, and that it was there in 1525 that he painted the Crucifixion for the high altar of the Oude Kerk.13 What Scorel’s presumed legal status in the workshop might have been is, of course, unknown, but it is difficult to comprehend how Scorel, as a shop subordinate, could have completed such a prestigious commission as an independent work. While it was customary for the master of a workshop to sell shop pieces under his own name, the reported instances of shop assistants selling their own works are almost nonexistent.14 Guild regulations prohibited assistants from working for their own profit, under penalty of fines.15 For Scorel to work on such an irregular basis would have been exceptional.

After Jan van Scorel returned from Rome in 1524, he had opportunities in Utrecht that cannot be disregarded. The contacts that Scorel made during his early travels, especially those in the Dutch circle that formed around the Dutch pope, Adrian VI, were put to immediate use by the young painter. After all, Scorel returned to the Netherlands as “canon of Utrecht”—as Scorel himself said in a letter from Rome dated May 26, 1524, just before his departure from that city. Pope Adrian VI, whose pontificate had lasted from 1522 until his untimely death in September 1523, had done what he could to ensure his protégé’s future. When still in Rome, Scorel must have met Willem van Lokhorst, the son of Herman van Lokhorst, vicar-general to the bishop of Utrecht, dean of Oudmunster, and an old schoolmate of Pope Adrian’s. Willem and his father were delegated to settle Adrian’s affairs in Utrecht, and it would have been appropriate and expedient for Scorel to present himself as a “beneficiary” with the expectation of a church prebend.16 It appears that lodging was not a problem for Scorel when he returned to the Netherlands, for, as Van Mander reports, Scorel “stayed in Utrecht with a deacon of the Oudemunster called Lochorst.”17 Finding a source of income was not a problem either, for within a few months of his return, Scorel secured a commission to paint organ wings for the church of Oudmunster,18 where none other than Herman van Lokhorst was dean. It is an inescapable conclusion that church connections facilitated Scorel’s seamless reintegration into the upper echelons of Netherlandish society.

In Dudok van Heel’s view, Jan van Scorel had to have painted the (lost) organ wings for Oudmunster in Amsterdam just before he began work on the Oude Kerk Crucifixion. It was not until 1526 that Scorel moved to Utrecht to paint the memorial altarpiece for Herman van Lokhorst, when Dudok van Heel presumes he set up shop in the immunity of Oudmunster, which would have been outside the jurisdiction of the guild.19 Yet if Scorel set up a workshop in the immunity of Oudmunster in 1526, he could have done that just as easily in 1524. And that is more likely. During the relatively short period from the autumn of 1524 to the spring of 1527, when Scorel moved to Haarlem, it can be estimated that Scorel completed up to six major commissions for churches in Utrecht.20

The payments concerning the organ wings for Oudmunster date from September 1524 and April 1525; they mention an offering of wine to the painter, who was present for the occasion and—it cannot be excluded—possibly living in Utrecht.21 The documents imply that Scorel was under contract, in which case he may have been bound by a common contractual clause not to take on any outside work. These wings, moreover, survived into the seventeenth century, when they are described—in a 1624 inventory listing possessions deriving from the dean of Oudmunster, Herman van Lokhorst—as “large.”22 It would surely have been more convenient to paint such large pieces on site. Around the same time, Scorel may also have received a commission to paint the exterior wings of Oudmunster’s high altar (now lost). Scholars have long felt that these wings were by Scorel, since a late sixteenth-century source describes them as including a portrait of Scorel’s patron, Pope Adrian VI.23 If so, then together with the organ wings and the Lokhorst Triptych (see fig. 12), Scorel would have completed three works in succession for Oudmunster or the Lokhorst family. Another work that could have been underway by late 1525 is the famous pair of group portraits depicting members of the Utrecht brotherhood of Jerusalem pilgrims;24 it would have been necessary for Scorel to be in Utrecht to take the likenesses of these twenty-four individuals.

The importance of the church to Scorel’s life and work cannot be underestimated. When Scorel returned from Rome, his immediate goal was to pursue a career in the church, which to him included painting as an integral activity. By August of 1525, he had already obtained the promise of the next available vicariate in the Mariakerk, although it took three more years before Scorel was installed in the office of canon.25 As a cleric, Scorel could produce paintings outside the jurisdiction of the guild and run a shop free from fees and limitations on the number of apprentices and assistants. This led to conflicts, as early sources suggest, but so far as we know he never joined the Saddlers’ Guild, the guild to which painters belonged in Utrecht, nor the Guild of St. Luke in Haarlem.26

Documents and early sources thus provide evidence of Scorel’s continuing activity in Utrecht during the critical years after his return from Italy, 1524–27. There is no documentation whatsoever suggesting a stay in Amsterdam.27 This in no way denies the close contacts that must have existed between Scorel and his former shop colleagues in Amsterdam. The painters may even have visited each other’s shops on occasion, where they could have studied closely held items such as drawings and workshop patterns. The distance between the two cities is not that great. The earliest firm date we have for Scorel’s influence on Jacob Cornelisz’s sons is 1526, but since it continues to appear in works that date into the early 1530s, these artists must have kept themselves informed about one another’s works over a period of years. A stay by Scorel in Amsterdam for two years, or up to two-thirds of this critical period, as a quasi-independent painter working in the shop of his former master or his master’s son, is highly unlikely.

Was Scorel’s Oude Kerk altarpiece a triptych or single panel?

According to Karel van Mander, Jan van Scorel painted the Oude Kerk altarpiece during his stay in Haarlem, from 1527 to 1530. He writes: “Schoorel . . . rented a house in Haarlem where he painted some large paintings: among others the high altarpiece for the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, a Crucifixion, a work that was highly praised: there is another painting of this still in Amsterdam with the same design.”28 Although Van Mander clearly speaks of a single painting and not a triptych, in Dudok van Heel’s view, the altarpiece must have been a triptych, since that was the norm for the early sixteenth century, and there are two Crucifixion triptychs that survive with Scorelesque compositions (see figs. 4 and 8). In his article, Dudok van Heel publishes a reconstruction of the altarpiece on the basis of these workshop replicas and later copies (to be discussed in more detail below) with the Carrying of the Cross and the Resurrection on the interior wings (fig. 3).

There are, however, viable reasons why Scorel could have delivered the Crucifixion as a single panel without wings. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that Scorel was contracted to paint a triptych—or a polyptych for that matter—and simply failed to deliver the wings. It is more likely, however, that the churchwardens planned for an altarpiece with wings and ordered the work to be done in phases. They would have commissioned Scorel to finish the middle panel and then have decided about the wings after its completion. Various examples of such practice are known.29 This was the case in November of 1537, when the churchwardens of the Oude Kerk contracted Maarten van Heemskerck “to paint the four sides of the inner wings” first and then continue, if the results were satisfactory, with “the two inner sides of the outer wings.”30 When Heemskerck was commissioned in 1538–41 to paint the gigantic St. Lawrence Altarpiece for the Grote or Sint-Laurenskerk in Alkmaar (now Cathedral, Linköping, Sweden), the order was given for parts of the altarpiece in three separate contracts.31 This may have been done because of the sheer size of the altarpiece and the need to secure funding, but each document still set up payments in installments and stipulated that the following contract would only be issued once the ordered work was sufficiently advanced or completed to the satisfaction of the churchwardens.

When the churchwardens decided around the mid-1530s to follow up on their plans for the Oude Kerk high altar, Scorel was living in Utrecht. By that time he had a flourishing painter’s workshop and had obtained full chapter rights as a canon in the Mariakerk. The office was no sinecure. He was, for instance, responsible for the administration of church properties in the Veluwe,32 and increasingly, from the mid-1530s on, was delegated to negotiate at various courts in the Netherlands on the chapter’s behalf. He acted as intermediary in the notorious “unicorn horn” affair.33 Scorel helped negotiate the recovery of church properties in Guelders, a project that continued over a period of years.34 When the churchwardens of the Oude Kerk approached Scorel about the yet-to-be completed altarpiece wings, he may have been too busy to take up the task. This would explain why they turned to Scorel’s former assistant, Maarten van Heemskerck, to complete the altarpiece. From the surviving contract, mentioned above, it appears that the painter agreed to deliver two interior and two outer wings, clearly defining the altarpiece as a polyptych with four wings. The St. Jerome Altarpiece by Jacob Cornelisz in Vienna, dated 1511, is a comparable work with four wings.35

Adding Heemskerck’s wings onto the two wings of Scorel’s presumed triptych would have been a challenge for the shrine workers who provided the panels and frames, since, as a glance at a few extant examples reveals, polyptychs are constructed as interlocking units. In Jacob Cornelisz’s St. Jerome Altarpiece, the slightly smaller set of interior wings nestle inside the profile of the outer set. Jan van Scorel’s six-winged altarpiece of Saints Stephen and James for Marchiennes, executed about 1539–42 (Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai), is the closest in format to what Dudok van Heel proposes for the Oude Kerk high altar. It has one set of wings that are stationary, and the middle wings have no frame at the central seam,36 easing the weight on the frame of the whole. Given the care with which contracts were written, it can be assumed the churchwardens of the Oude Kerk would have found ways to avoid changing plans midstream from a triptych to a six-winged polyptych.

Another passage from Van Mander confirms that the altarpiece never had any wings that were painted by Scorel. Van Mander writes in his account of the life of Maarten van Heemskerck: “In Amsterdam, in the Oude Kerk, there were two double shutters by him with passion scenes and the Resurrection on the inside; . . . The middle panel was a Crucifixion by Schoorel.”37 This provides still more evidence that Scorel’s contribution to the altarpiece was a single panel—the middle panel—and not a triptych. Nor did the fictive triptych have a Carrying of the Cross and the Resurrection on the wings, for if they had already existed, there would have been no reason for Heemskerck to add wings with the same subjects.

Which Crucifixion is which?

There are two Crucifixion types that have been associated with Scorel’s lost altarpiece for the Oude Kerk. A third composition is occasionally mentioned in the literature, but it more likely relates to a Crucifixion that Van Mander said Scorel did later in his career, for Arras.38 The first Crucifixion type is historiated; it has many small figures and episodes, and the thieves have been positioned so that they turn inward toward Christ. The second type is more iconic; the figures are larger and closer to the picture plane, and the thieves turn away from Christ. In this paper, the types will be called small- and large-figure Crucifixions.

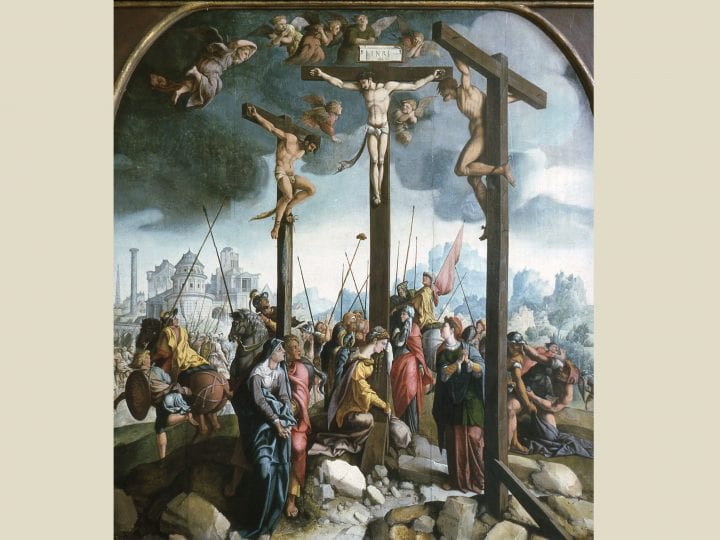

There are up to seven replicas or copies of the large-figure Crucifixion. One survives as the middle panel of a triptych (formerly Begijnhof, Amsterdam, and now at the Kathedraal Museum Nieuwe Bavo, Haarlem; fig. 4); its interior wings depict the Carrying of the Cross on the left and the Resurrection on the right, while Adam and Eve appear on the exterior. The small-figure Crucifixion is known to us through two versions. One is a shop replica or possibly a later copy, now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn (fig. 5), and the second is a workshop replica that forms the middle panel of a triptych with Carthusian monks in the Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht (fig. 8).

Recently, a small version of the Carrying of the Cross appeared on the art market that clearly figures into this discussion (fig. 6). Dudok van Heel believes this panel has “the aura of a modello,” perhaps because of its small size.39 To him it predicts the composition of the left wing of the presumed triptych Scorel painted for the Oude Kerk (see fig. 3). Dendrochronology exists for this work, but unfortunately, it is an example of a too-early dating, with an estimate of the wood’s use by about 1510, when Scorel was still a shop assistant.40 Stylistically, the painting must date much later. The composition is not based on the juxtaposition of near and far seen in Scorel’s earlier works (and that can still be sensed in the Rest on the Flight into Egypt paintings) but is more akin to works from the early 1530s, such as the Adoration of Magi discussed below (see fig. 13). The underdrawing in the Carrying is loosely sketched in black chalk; it is not impossible that it is by Scorel himself, but a shop assistant cannot be excluded (figs. 7a–b).41 Regardless of attribution, the underdrawing—in type—belongs to the period in or after Scorel’s stay in Haarlem, when his layouts include long, undulating contours and systematized hatching.42 This makes it highly unlikely that this version of the Carrying of the Cross could be associated in any way with an Oude Kerk commission that dates as early as 1525. Furthermore, X-radiographs have revealed the traces of an Adam figure on the reverse of the panel that exactly match the Adam on the exterior of the triptych formerly in the Begijnhof.43 The Carrying of the Cross was thus a finished wing and, as such, should more reasonably be grouped with the many versions of the subject, either as “original” replicas—that is, workshop replicas—or copies produced outside the workshop.

There are at least six versions of the Carrying of the Cross and somewhat fewer of the Resurrection. Comparing their sizes and formats leads to some interesting observations.44 Using the smallest of the examples as a basis, entire compositions of three replicas or copies have been enlarged exactly. This would have been accomplished by squaring, which was a method that Scorel knew from the beginning of his career and that he and his shop employed frequently.45 Two of the versions were created differently: elements of the composition were divided and rescaled separately so that the figures were larger in relation to the background. In these cases, figures were also deleted and/or added. Given the efficient method of replication used by Scorel’s shop and the number of surviving replicas and copies, Scorel’s workshop must have been called upon frequently to produce Crucifixion triptychs.

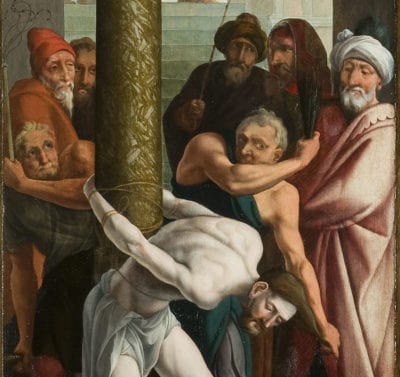

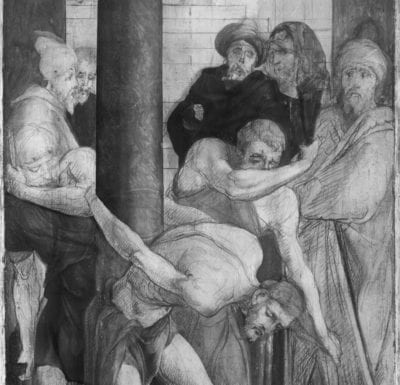

Of these, the Crucifixion Triptych with Carthusians is essential to the argument presented here because it is, first, a verifiable ensemble and, secondly, a work in which the master of the shop’s decisive role is clearly evident. It combines a workshop replica of the small-figure Crucifixion with newly designed compositions for the wings: the Carrying of the Cross and Resurrection on the interior and Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane and Flagellation on the exterior (figs. 8–9). Jan van Scorel gave special attention to the exterior scenes, as he was obliged to restructure the Passion narrative to include the figure of a Carthusian donor. He worked out the underdrawings in detail, painted figures, and made critical changes in faces and heads. In the Flagellation, most of the heads—the purview of Scorel himself—were altered significantly (figs. 10a–b).46Many of the changes were made in a late paint stage, since a first paint stage followed the underdrawing. In the finalized image, Christ’s two persecutors look up and out at the viewer instead of looking down, as in the underdrawing. One of the figures just above the torturer on the left was underdrawn in profile; Scorel transformed this head into a striking character study who, like the turbaned figure on the right edge, glances toward Christ. They close the ring of bystanders who, along with Pilate in the center background, are complicit in Christ’s torment. The late 1530s date given by Faries to the wings has since been substantiated by dendrochronology, while the middle panel may date somewhat earlier.47

The figures on the wings of the Utrecht Crucifixion Triptych are much larger than those in the middle panel. They appear, in fact, to better match the large-figure Crucifixion, which might indicate that it was the original rather than the small-figure version that had wings. In attempting to account for the mismatch, Dudok van Heel speculates that the triptych was incorrectly framed or re-framed, possibly in the nineteenth century, and that the middle panel originally had a predella, requiring the wings to be lowered in position.48 However, in the opinion of the conservators who treated the triptych when it was restored in 2008, the frame of the triptych is original (see the Appendix by Caroline van der Elst). All the hinges are original and show no signs of having been repositioned. The wing panels were painted in their frames, and dendrochronology confirms that the wood of the wing panels and frames dates from the same period—the early sixteenth century.49 There is thus no reason to postulate any radical change in format.50 Assuming, then, that the Carthusians wished to have a copy of the Oude Kerk altarpiece for their triptych, there was clearly a replica available for the middle panel but no models for matching wings. The wings Scorel provided are similar in composition to other works close in date, such as the wings for the 1539–42 polyptych with Saints Stephen and James.

The reconstruction proposed by Dudok van Heel has elements that are questionable (see fig. 3). The reconstruction combines the Carrying of the Cross, in a private collection, as the left wing (fig. 6), matched to a small-figure Crucifixion (based on the Bonn panel, fig. 5) and a Resurrection (based on the right wing of the triptych formerly in the Begijnhof, fig. 4). Although somewhat persuasive at first glance, closer study reveals a difference in figure scale between the middle panel and wings. In addition, a strip has been added to the right wing in the reconstruction, and a strip has been cut off the right side of the left wing. If that edge had been included, it would be obvious that the horizon drops off so sharply that it cannot link with the middle panel (fig. 11). A triptych that supposedly dates from the period of Jan van Scorel’s Lokhorst Triptych would have had a continuous background from panel to panel (see fig. 12).51

There is, moreover, no basis for the assumption that the Oude Kerk altarpiece had a lobed top. The present shape of the small-figure Crucifixion in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn (see fig. 5) led Dudok van Heel to speculate that the original top must have been cut off and that the panel’s curved upper corners would have continued into the lobed shape that is often seen in triptychs produced by Jacob Cornelisz’s family shops.52 However, the catalogue of the Bonn museum clearly states that the top of the panel was altered in a different way.53 The corners were cut and rounded at a later date, and a semicircular piece was added to the upper edge so that the panel could fit into a baroque framework once in the church of the former Premonstratensian abbey of Steinfeld (Kall, Germany), which is where the panel was found.54 The straight edge at the top is the original edge, and the panel’s original shape was rectangular, as in the version of the Crucifixion in Utrecht.

The small-figure Crucifixion, as represented by the surviving panels in Utrecht and Bonn as well as the middle panel of Dudok van Heel’s hypothetical triptych, cannot be proven to have had matching wings. It is thus possible that the original of this composition existed at some point as a single panel. Since Van Mander describes Jan van Scorel’s painting for the Oude Kerk as a single panel and not as a triptych, it follows that the Crucifixions in Utrecht and Bonn may be replicas of this altarpiece.

When and where was Scorel’s Oude Kerk Crucifixion painted?

Could the Oude Kerk small-figure Crucifixion date as early as about 1525? Most likely not, for it is difficult to see how the Crucifixion could precede the only surviving work by Scorel that is close in date, the Lokhorst Triptych of about 1526 (fig. 12).55 The composition of the middle panel of the Lokhorst altarpiece repeats a spatial convention that still has ties with Scorel’s earliest works. The map-like vista of Jerusalem that extends across the background is in actuality the last of the bird’s-eye-view panoramas that characterize the painter’s landscapes done in Italy around a half decade earlier.56 It is a type that is not seen again until some very late landscapes associated with Scorel and his workshop. The Crucifixion exhibits differences in the construction of space. The horizon is lower, and the distant buildings have been brought forward in space to form the middle ground. The foreground hill may be a vestige of a traditional “plateau composition,” but in this case it links to the middle ground by a series of coulisses that act as stepping stones into the distance. These features have more in common with works that derive from Scorel’s Haarlem period and from the early 1530s, such as the Adoration of the Magi, as represented by the version at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin (fig. 13).57 Aside from the gate on the right side of the Adoration, which introduces an additional step into space, the distant buildings are on the same scale as in the Crucifixion. The buildup of rocks in the foreground of both works is also quite comparable. The meandering of figures back and forth in space in the Crucifixion is more like the measured distribution of figures in space in the Adoration of the Magi than the clumping of apostles into a tight mass in the Lokhorst Triptych. Overall, Scorel’s design for the Crucifixion has moved away from the landscape convention of the Lokhorst Triptych toward the direction of later works.

Scorel’s Crucifixion for the Oude Kerk does not seem to have had the widespread influence that his Holy Family had, as described at the beginning of this article. If the altarpiece had in fact been created in Amsterdam, in one of Jacob Cornelisz’s family workshops, why are there no echoes in paintings by the master or his assistants of what must have been a magnificent work? The Crucifixion could not have served as the model for the landscapes in the Madonna and Child compositions attributed to Cornelis Buys IV and Dirck Jacobsz, for the antique buildings seen in these paintings are entirely different and are placed much deeper in space.

More relevant clues about influence come from Haarlem, which is of course where Van Mander said Scorel painted the altarpiece for the Oude Kerk, and specifically from the early paintings of Maarten van Heemskerck. Dudok van Heel speculates that Heemskerck could not have joined Jan van Scorel in Haarlem because Scorel never had a commercial shop there, painting instead exclusively for the commander of the Order of St. John.58 Art historians used to hold a similar view about Geertgen tot Sint Jans until recent research showed that Geertgen must have had a shop with apprentices and/or assistants.59 Maarten van Heemskerck was only three years younger than Scorel and would have been around twenty-nine years old when Scorel moved to Haarlem in 1527. He was fully trained by this time, having studied with two painters, one in Haarlem and one in Delft. Van Mander tells us that when Heemskerck heard about the “beautiful, novel manner of working” that Scorel had brought from Italy, he went to Haarlem and contacted the artist.60 He may have lodged in the house that Van Mander said Scorel rented in Haarlem to take on students.61 Heemskerck could not have been Scorel’s pupil (i.e., apprentice)—he was old enough to be an independent master—but his position was that of Scorel’s assistant, as has been stated repeatedly in the literature.62 It was during this period, in the words of Jeff Harrison, that Heemskerck formed the “nucleus of images” that he used and re-used over the course of his career.63 Technical studies have also revealed telling carryovers in underdrawing and painting technique from Scorel to Heemskerck that imply a workshop connection. Heemskerck executed underdrawings at the same stage in the painting process as Scorel, on top of a white priming layer, and frequently used long, overlapping curves to define forms.64

Two early paintings by Maarten van Heemskerck play a critical role in our argument: the Christ on Calvary in Detroit (fig. 14), and the Lamentation with Donor, which is known to us through what is considered to be a seventeenth-century copy in the Museum Catharijneconvent (fig. 15). The differences in style suggest that some time elapsed between the two works. Because of the dominant influence of Scorel’s Lokhorst Triptych of about 1526, the Christ on Calvary must date soon afterwards; that is, close to the beginning of the period when Heemskerck could have come into contact with Scorel in Haarlem, about 1527.65 With its monumental figures, the (original of the) Lamentation has been dated around 1530–32,66 at the time or just after Scorel left Haarlem in 1530.

One can assume that if Scorel’s Crucifixion for the Oude Kerk had been completed before Heemskerck painted his early Calvary, it would have been a famous example that the artist could hardly have ignored. But he apparently did not know it.67 Heemskerck’s Calvary is actually a different subject: the painter omits the two thieves and surrounding figures and portrays the devotional encounter between the Virgin Mary and St. John and the isolated figure of Christ, who is seen at an angle across space and from a low viewpoint. The cross seems truncated, partly because of the Magdalen’s overly large figure at its foot, a mistake Heemskerck would have avoided if he had been able to consult Scorel’s picture. Images of the crucified Christ seen on a diagonal, such as Gerard David’s Crucifixion (c. 1515) and Lucas van Leyden’s print in the Round Passion (1509), are likely models for Heemskerck’s representation,68 but the most immediate source is Jacob Cornelisz’s Calvary in Ghent, which dates to about 1524 (fig. 16).69 There Christ also hangs from a diagonally positioned cross and is seen from below, and, like Heemskerck’s Christ, shows no trace of Italianate influence but is a rather limp, pitiable figure. The situation was different when Heemskerck painted his Lamentation with Donor. Three crosses appear in the background; they tower above the foreground figures and are offset to one side and placed on a diagonal, as in Scorel’s small-figure Crucifixion. More important, the pose of Heemskerck’s thief on the left is identical to Scorel’s thief on the right, only in reverse.70 Here we have the evidence clinching the small-figure Crucifixion as the Oude Kerk altarpiece and establishing a date for it close to the end of Scorel’s stay in Haarlem, around 1530.

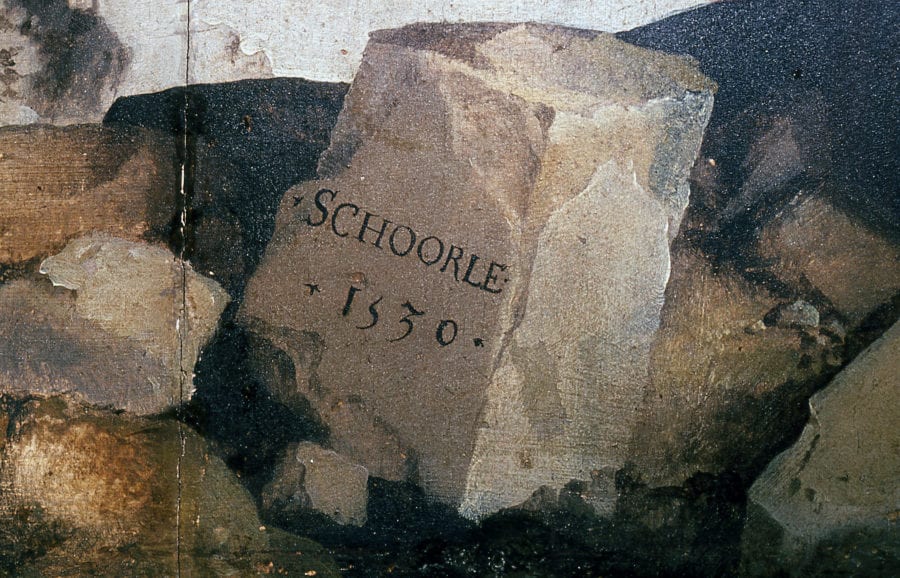

It is important to note that the Bonn Crucifixion has a signature and date: “Schoorle / 1530” (fig. 17). Scorel’s name is spelled almost exactly as it is written in documents from the Mariakerk, and the form of the numerals, especially the “5” and “3,” is very close to that in other dated works from the period. Study with infrared and ultraviolet does not suggest that the signature and date are later additions.71 Since scholars often assume dates on copies indicate the date of the original,72 this may also be the case with Scorel’s Crucifixion.

Heemskerck was influenced again in 1540 by Scorel’s Oude Kerk painting when he completed his Crucifixion for the monumental St. Lawrence Altarpiece (fig. 18),73 which displays Heemskerck’s full-blown post-Roman Mannerist style. Although both thieves face inward toward Christ, as in Scorel’s Oude Kerk painting, their poses are much more contorted, revealing Heemskerck’s own studies of Italian masters, such as Michelangelo, when he was in Rome from 1532 to 1536. Figures are now larger and pushed toward the foreground, which is a tendency of both Scorel and Heemskerck around 1540. Still, the references to Scorel’s Crucifixion are clear. Heemskerck marks out space similarly by placing the crosses on a diagonal leading into distance. He includes some of the same episodes in the same positions, such as the soldiers fighting for Christ’s robe on the right and soldiers on rearing horses on the left. Mary and John stand at the foot of the cross on the left while the Magdalen clings to Christ’s cross near the center. Like Scorel, Heemskerck sets off the heads and lances of the Roman soldiers against the brilliance of the distant landscape, where there is a glimpse of an Italianate Jerusalem. It is possible that Heemskerck first became acquainted with the Oude Kerk Crucifixion when he was Scorel’s assistant in Haarlem, and he may even have collaborated in its production. In any case, he could have studied the Crucifixion after 1537, when he was at work on the wings of the Amsterdam altarpiece. In 1543, Heemskerck produced another gigantic Crucifixion panel, over three meters high (Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent), which Harrison calls a “reprise” of the Linköping painting in composition, imagery and style.74 The addition of a donor in the lower left corner does not alter the basic placement of figures, and Heemskerck again places the crosses on a diagonal and sets off the Roman soldiers on the crest of the hill of Calvary against a brilliant sky that darkens dramatically as it rises higher on the panel. Heemskerck would revisit the subject of the Crucifixion at least seven more times in his long career,75 and many of the same compositional elements and iconographic motifs survive in these later works.

How reliable is Karel van Mander?

Dudok van Heel claims that Karel van Mander was misinformed about the high altar of the Oude Kerk because he had never seen the altarpiece himself and had no choice but to rely on secondhand accounts and the distant memories of the elderly. This older generation, according to Dudok van Heel, included the descendants of the churchwardens who gave the commission for the painting of the altar wings in 1537. These individuals were loyal Catholics who were banned from Amsterdam at the time of the Alteration in 1578 and who went, for the most part, to live with relatives in Haarlem. Karel van Mander, Dudok van Heel argues, would have had no contact with these Catholics.76 There is much to dispute here. Amsterdammers who were born in the 1540s were twenty in the 1560s—when the altarpiece still existed—and sixty-plus around 1600, and thus not so far removed in time that they could no longer remember what the altarpiece looked like. There is also no need to assume that only exiled Catholics in Haarlem could remember the altar. There were many in their sixties in Amsterdam who had known the altar and who could provide Karel van Mander with a good description.

Van Mander’s many informants no doubt included family members of Jan van Scorel in Utrecht. The biographer should be credited in particular for his detailed knowledge about the format of paintings. He knew, for instance, that Scorel’s altarpieces for the Benedictine abbey of Marchiennes in Artois (now France) included a single panel, a triptych, and a polyptych with six wings. Memories of these works installed at a great distance from Utrecht may have been kept alive by someone like Scorel’s grandson, Johan van Sijpenes, who was a canon like his grandfather and had studied in nearby Douai in 1595–99.77

As the evidence mounts, there is less and less reason to doubt Karel van Mander’s description of the high altar of the Oude Kerk. We may never be able to learn much about the wings Maarten van Heemskerck added, since no replicas or copies survive, but we can be assured they completed the ensemble as a four-winged polyptych. Since there never was any triptych by Scorel, the motive disappears for the theory that Heemskerck was commissioned to add wings to the altarpiece in order to suppress the images of Adam and Eve and any associations they might conjure up of the Anabaptist riots of 1535. In February of that year, the so-called naaktlopers (“streakers”) ran naked into the streets as a form of protest and, according to Dudok van Heel, left a lasting impression in Amsterdam.78 If that had been the case, there were easier solutions: one could simply paint over the offending images.

Conclusion

One of the more gratifying conclusions of this research is the vindication of Van Mander’s account. Van Mander’s description of the Oude Kerk altarpiece and the time and place it was painted have all proved to be credible. This not only reaffirms the continuing usefulness of this essential source for our field; it also correlates with the findings of other studies about the reliability of Karel van Mander’s writings.79

The recovery of information about two of the lost works from the period after Jan van Scorel’s return to the Netherlands leads to new insights. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt compositions discussed at the outset of this paper were inspired by Scorel’s lost wings for the Mariakerk in Utrecht. They mark the beginning of the reorientation of imagery in Jacob Cornelisz’s family workshops at the hands of Scorel’s former coworkers. The influence of Scorel’s Oude Kerk Crucifixion on his colleague-assistant Maarten van Heemskerck is also instantaneous as well as lasting, as seen in Heemskerck’s repetitions of the subject over a period of years. Without the identification of these lost works, the immediate reception of Scorel’s new Italianate style by painter colleagues of his own generation would not be fully recognized.

The appearance of Jan van Scorel’s Crucifixion for the Oude Kerk is now known, but one can only imagine the solemn grandeur of the altarpiece in its original setting. It was large—that is one more part of Van Mander’s description that we can believe. Scorel was known to have painted life-size figures around this time, and it is not impossible that Scorel was working close to or on this scale for the prestigious Amsterdam commission. With the painting placed high above an altar, the towering height of the crosses would have been even more exaggerated. Silhouetted against the darkening clouds, the thieves are almost mirror images of each other, one leg stretched out and the other bent. Their sophisticated anatomy was praised some years later by Peter Opmeer (1529–1595), who expressed his admiration in terms of an artistic conceit: the thief to Christ’s right was depicted so that one could see his backbone and his chest at the same time.80 Bright, pure colors punctuate the milling crowd of figures at the foot of Christ’s cross, particularly reds, blues, and yellows. Scorel’s indebtedness to Raphael can be sensed in the decorous poses of the main protagonists, and the running figure on the left edge and the horse next to him are exact quotations from Raphael’s tapestry of the Conversion of Paul.81 The diagonal created by the crosses leads over the hill of Calvary to a luminous landscape in the background, where the transition from light green to icy blue in the distant mountains suggests that the farthest peaks may have been painted in the original with natural ultramarine, as was the case in other landscapes from Scorel’s Haarlem period (fig. 19).82 Scorel has placed recognizable monuments on the far left: a column, an obelisk, the pyramid of Cestius, and a portico reminiscent of that of the Pantheon. Here, for the first time in Scorel’s works, Jerusalem has become Rome. There can be little doubt that what was destroyed in 1566 was one of Jan van Scorel’s major works.

Scorel’s Crucifixion for the Oude Kerk embodies the ambition of his oeuvre as a whole. By departing from local traditions and by situating events in a setting that evokes the past glory of a legendary civilization, Scorel aggrandizes his subjects and aligns his work with the mainstream of European art.