Ledgers from the Milanese bank Filippo Borromei and Company of Bruges and London have been transcribed by James Bolton and Francesco Guidi Bruscoli as part of the Borromei Research Project at Queen Mary, University of London. The ledger for Bruges, dated 1438, offers information about the financial activities of the Giustiniani family of Genoa and names Raffaello Giustiniani as the member of the family based in Bruges. This article explores the context of this new piece of evidence, which offers a fresh perspective on the potential connection between this Genoese family and the Bruges workshop of Jan van Eyck.

The Virgin and Child with Saints Catherine and Michael and a Donor in Dresden is the only surviving triptych identified with Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441)(fig. 1). The altarpiece measures 33 x 27.5 x 5 cm when the wings are folded to enclose the central panel (fig. 2). The central frame bears the painter’s signature, his device, ALC IXH XAN (“as well as I can”), and the year of completion, 1437. The frames of the wings are distinguished by two coats of arms, one of which is associated with the Giustiniani family of Genoa (fig. 3). Since the mid-nineteenth century, German scholars have consistently tried to clarify the relationship between the coats of arms and the image of the donor in the left-hand panel.1 He is portrayed in a fashionable green houppelande with a red hood, kneeling directly in front of the Archangel Michael. To date, researchers continue to search for evidence that can connect the commission with the mercantile activities of the Giustiniani. In advance of the most recent contributions to scholarship on the triptych in 2000 and 2005, Uta Neidhardt and Christoph Schölzel guessed that the key to the donor’s identity lay in as-yet unexamined archival evidence.2 They asked “Who was the donor of the Dresden altarpiece?” and went on to state that “The question is still not answered, since nothing said previously can make concrete the identity of the man who is represented. In the end we come back to the coat of arms, which is part of the original frame. Returning to the thesis of the Giustiniani as the merchant family who gave the commission is, however, impossible without further information….[I]t is undoubtedly only a matter of time until this purely archival problem is resolved.”3

This “archival problem” is one faced by all historians of early Netherlandish painting, primarily because vast quantities of objects and their associated documentation have been dispersed and/or destroyed.4 However, the recent transcription of a Bruges ledger for the Milanese bank Filippo Borromei and Company offers promising new information.5 The ledger for 1438 records a range of transactions that refer directly to the Giustiniani family of Genoa, and, significantly, this ledger contains one entry that singles out a particular member of the family. An entry dated August 25, 1438, refers directly to Raffaello Giustiniani “of Bruges.”6

This article sets out the scholarly debates that have surrounded the Dresden Triptych before exploring the possibility that the Borromei ledger offers a plausible identity for a person involved in the commission. It begins with a brief discussion of the known provenance and scholarship related to the altarpiece before considering the evidence in the Borromei ledger in the context of contemporary events in the Burgundian Netherlands.7 The Borromei accounts point directly to the Giustiniani circle active in Bruges and perhaps indirectly to a connection between this Genoese family and the Bruges workshop of Jan van Eyck.

Historical Debates

The Dresden Triptych is thought to be one of the two items sent to Vincenzo I Gonzaga by his agent, Lodovico Cremasco, from Rome on May 10, 1597; and an altarpiece matching its description was recorded in an inventory of the Gonzaga collection on its sale to Charles I of England thirty years later.8 While the triptych was part of the English royal collection, the collector’s mark of Charles I was placed on the outer edge of the right-hand wing and after the regicide and dispersal of the collection, the painting eventually came into the possession of the Saxon Electors. It was first recorded in Dresden in 1754 as a work by Albrecht Dürer, an attribution that continued to be accepted until the Berlin archaeologist/historian Aloys Hirt reattributed it to van Eyck in 1830.9 In the 1840s, the Dresden painter Eduard Bendemann was tasked with reconstructing at least three areas of loss in the Virgin’s gown,10 and it is likely that a temporary ebony frame was attached at this time (1844).11

The temporary frame appears to have been designed to protect the marbling of the original frames and their inscriptions, which imitate precious gold work. These were not concealed by the ebony frame, thus allowing Max Friedländer to describe the texts when he began to publish the fourteen volumes of Die altniederländische Malerei in 1924. The outer frame of the central panel bears the text: “Hec est speciosor sole et sup(er) o(mn)em stellaru(m) dispositionem…” (She is more beautiful than the sun, and above all the order of the stars…) from the Book of Wisdom/Song of Solomon, lines that also appear in the inscriptions on the Virgin in the Ghent Altarpiece and on the frame of the Van der Paele Madonna.12 On the wing with Saint Catherine can be read the words “Virgo prudens anelavit ad sedem siderea(m)…” (The prudent virgin has longed for the starry throne…), a text that is derived from the liturgy for the service of vespers on November 25, this saint’s name day. The text on the donor wing comes from the Roman breviary for the Dedication Feast of Saint Michael: “Hic est archangelus princeps milici(a)e angelorum…” (This is Michael the Archangel, leader of the angelic hosts…). According to Carol Purtle, each of these texts was in contemporary use at Saint Donatian’s in Bruges.13

The coats of arms were also evidently not covered by the lip of the temporary frame because in 1863 Hugo Bürkner published drawings of them in his catalogue for the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden.14 Since this time, many scholars have searched for a connection between the the Giustiniani arms on the frame and the identity of the donor. Ludwig Kaemmerer was the first to claim, at the end of the nineteenth century, that the donor was “a Michel Giustiniani, son of Marco, [who] lived from 1400,” a supposition echoed by W. H. James Weale.15 August Schmarsow went a step further, linking the triptych to Genoa and dating it to 1427, when he maintained that van Eyck traveled there.16 He also stated that “the first documentary evidence of a Michele Giustiniani in Genoa dates to the beginning of the [twentieth] century,” although he did not specify the nature of this evidence or its source.17 The same potentially relevant link between the donor and the saint standing at his shoulder was referred to by Roberto Weiss in his 1956 article “Jan van Eyck and the Italians.” Weiss cited a petition in the State Archives in Genoa, which was filed in 1430 by a Michele Giustiniani, requesting permission to live in Genoa.18 From this, Weiss deduced that the man had been born and brought up in Bruges and was therefore most likely the donor of the triptych, which he thought predated the petition.19 The proposition that this Michele was the donor does not preclude a later date for the painting, but it must be said that Weiss’s proposal was stronger before the date 1437 was uncovered on the central frame in the late 1950s.20

While Schmarsow and Weiss considered the Dresden Triptych to date before 1430, and Friedländer could “unhesitatingly range it between the Arnolfini painting in London (1434) and the van der Paele altarpiece (1436),”21 questions about its date were finally answered in 1959 when the temporary frame and the dark brown paint on the inner molding of the central frame were removed.22 Given the early misidentification and ongoing questions over the triptych’s date, it seems that portions of the frame had been covered with a uniform brown paint for centuries. But soon after the triptych was returned to Dresden from Moscow, where it was taken after the Second World War, the overpaint was removed to reveal van Eyck’s name, a date, and his device: Johannes de eyck me fecit et c(o)mplevit Anno DmM–CCC–XXXVII·ALC·IXH·XAN.23 This express statement of a year of completion placed this triptych near the end of van Eyck’s œuvre rather than somewhere in the middle. Even with this knowledge, the damaged state of the coats of arms has continued to frustrate efforts to establish a provenance.

With this problem in mind, Christoph Schölzel examined the panels and frames under a microscope in 1998, observing that the coats of arms, like the frame texts, appear to have been painted directly onto a brown-colored bole or ground.24 He determined that the shields are “organically integrated” with the inscriptions and that they show the same type of highlights on the characters painted to look like embossed letters. To aid his examination, Schölzel prepared scale reconstructions, based on his own observations and on the drawings published in Bürkner (fig. 3). While the blazon on the Saint Catherine wing remains unidentified, that on the wing depicting the donor – a castle with three towers surmounted by an eagle with outstretched wings – is undoubtedly that of the Giustiniani. Of course, Schölzel’s observations cannot be confirmed without a paint sample to help establish whether or not a varnish or dirt layer exists between the marbling and the base tone used for the original coats of arms. Nonetheless, based on visible evidence in the painted surface and in areas of loss, Schölzel concluded that the coats of arms on both wing frames are contemporary with the painting.25

If the Giustiniani arms are, as seems likely, contemporary with the original composition, they can indeed be seen as a clue to the relationship between the image of the donor and the Giustiniani family of Genoa. However, it is still open to question whether Michele Giustiniani returned on occasion to Bruges and possibly commissioned the altarpiece during such a visit; whether he directed a family member to act on his behalf; or, alternatively, whether another individual altogether was responsible for the commission. Nothing substantive has been found to situate the activities of a Michele Giustiniani in Bruges after 1430, and while it is, at present, not possible to verify other proposals, it is worth considering the possibility that another member of the Genoese Giustiniani family who was resident in Bruges acted as an intermediary or commissioned the altarpiece for himself from Jan van Eyck.

The Giustiniani of Genoa

At least two lines of the Giustiniani family, including the Venetian and Genoese branches, were active in Bruges in the second quarter of the fifteenth century.26 The Giustiniani of Genoa can be traced to the traders who gained control of the island of Chios in 1346, when a flotilla led by Simon Vignoso conquered both the island and the port of Phokaea (Foça) on the mainland.27 The strategic location of Chios, en route to Constantinople, enabled the Genoese to compete with Venice for a share of trade in the Levant and Black Sea. The Republic of Genoa would not pay the traders for their victory, but on February 26, 1347, the republic granted them the revenues from Chios and Phokaea.28 This arrangement allowed the Giustiniani to manage the two territories directly and gather substantial income from their distribution of gum mastic and alum, which were shipped across Europe.

To manage Chios, twelve Genoese nobles formed a private trading society, which ultimately bound them into a financial and political “family.” Nicolò de Caneto de Lavagna, Giovanni Campi, Francesco Arangio, Nicolò di S. Teodoro, Gabriele Adorno, Paolo Banca, Tommaso Longo, Andriolo Campi, Raffaello de Forneto, Luchino Negro, Pietro Oliverio, and Francesco Garibaldi adopted a coat of arms depicting a castle surmounted by an eagle. Significantly, too, they adopted the name Giustiniani, as if “they were born from the same father and the same mother,” with a contract stipulating that this name would not be passed by right of birth from one generation to the next.29 Instead, each man’s share in the mercantile society was transferable and could be sold, making this a republican nobility, as opposed to a feudal one. It is not clear when the name of the Genoese Giustiniani became, like that of the Venetian line, hereditary and dynastic, but by the late fifteenth century the Giustiniani of Genoa had acquired noble status and vast amounts of land in and around this international port.

One question that Neidhardt and Schölzel posed is whether there might be a connection between the Giustiniani and the Adornes, who had been established in Bruges since the second half of the thirteenth century.30 They noted that Jan Rotsaert had drawn connections between the Adornes and the Alexandrian princess Saint Catherine, who was legendary for her learning and was the patron saint of theologians, philosophers, and professors.31 They also discussed the similarities between the position of the donor, especially the hands, and the figure of Saint Francis in Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, a version of which belonged to Anselm Adornes (1424–1483).32 Ultimately, Neidhardt and Schölzel concluded that the donor could not be identified directly with the Adornes family of Bruges. They did not, however, note that the list of original signatories of the Giustiniani contract of 1347 included one Gabriele Adorno, which meant that less than a century earlier, a Genoese Adornes had, by contract, become a Giustiniani.

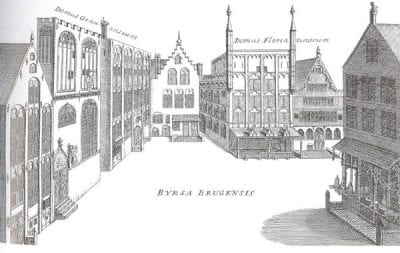

Whether the successors to the signatories still considered themselves to be connected a century later is unclear. Undoubtedly, though, members of the Genoese community resident in Bruges would have maintained connections through the Genoese trading house on the Beursplein at Vlamingstraat 33 (fig. 4). The activities of Genoese traders who traveled between Genoa and the North Sea in semiannual convoys would have been administered from this location, as were those of Genoese residents of the city. Thus it is likely that this small, regionally defined group, who often sailed together on voyages lasting approximately fifty days, would have had at least a passing familiarity with one another, as well as with other members of the Genoese community in Bruges.

The Archangel Michael

An understanding of the origins of the Giustiniani family as a patrician trading society on Chios might help to unravel the association of the donor in the Dresden Triptych with Saint Michael. Traditionally, a representation of a saint would identify him or her as the namesake protector of the secular donor, but here the figure of Saint Michael might have broader significance. Saint Michael, together with Saint George, was emblematic of chivalry and the glorification of knighthood. He was also regarded as protector of all believers and, in the Eastern Orthodox Church, especially at Constantinople, he was considered “the great heavenly physician.”33 Given the Giustiniani connection to Chios and their trade in mastic (the island’s principal resource, known for its medicinal properties), perhaps the significance of this saint was linked to the Greek Orthodox tradition, rather than to the given name of the donor. The choice of Saint Michael might therefore be understood in the context of both the noble society that formed the basis of Giustiniani familial connections and the context of protection for a group that was collectively displaced, whether on Chios, in Bruges, or in Antwerp.34 It goes without saying that the representation of Saint Michael remains an obstacle to the identification of the donor as an individual who did not bear this name. However, this issue might be addressed through further enquiries that focus on contemporary Genoese merchants who sought the archangel’s protection.

Giustiniani and the Borromei Ledger for 1438

Considerably more evidence than is currently available would be necessary to establish a sound relationship between the activities of the Giustiniani in Bruges in the late 1430s and a person with a role in the commissioning of the Dresden Triptych from van Eyck. The Michele Giustiniani identified by Weiss had apparently returned to Genoa after 1430, and until now, no evidence had come to light for any member of the family who resided in Bruges at roughly the time that the triptych was completed. For this reason, the reference to Raffaello Giustiniani in the Borromei ledger, as the one member of the family located in Bruges in the late 1430s, is worthy of investigation.35

The Borromei-Bruges accounts for Giustiniani transactions carry over from 1437, a tense period in Bruges given the impact of the sanctions imposed by the duke in the wake of a revolt the year before.36 By mid-1437, if not earlier, foreign merchants who had customarily been based in Bruges are thought to have transferred many of their activities to Antwerp, Middelburg, or London to protect their financial interests.37 The 1438 ledger records activities from January 1 through the Antwerp spring fair and into the autumn of 1438. Recorded transactions include the names of Giustiniani family members involved in delivering or collecting goods, probably quantities of cloth but also oil. Among them is Antonio Giustiniani of Genoa, who was a ship owner,38 as well as Agostino, Amerigo, Damiano, Domenico, Francesco, Giannino, Niccoló, and Simone, all thought to have been based in Genoa. Only Raffaello is identified as being based in Flanders, a status confirmed by one reference to him as Raffaello Giustiniani “of Bruges.”39

The Borromei current account for Raffaello Giustiniani begins on January 1, 1438, with a debit of £50.0s.0d. (all amounts given in Flemish pounds) carried over from the previous year.40 In January and February, Raffaello was writing letters from Middelburg (rather than Bruges) and receiving payments there.41 At Middelburg in February 1438, he issued a bill of exchange to the deliverers of goods from Seville and from the papal court on behalf of Domenico Giustiniani and one Beldesino Maruffo.42 By June, he had paid a sum into the Borromei Antwerp account, presumably after the Whitsun fair,43 and in July he settled an account between Jacopo and Girolamo Lomellino.44 In July and August, Raffaello accepted deliveries from Francesco de’ Fornari of Genoa for Giovanni Ventura and Company of Barcelona and Avignon,45 and between June and December, he acted as “deliverer” of goods either to the bank itself, or to the bank and Ricci and Company of Avignon on behalf of Domenico Giustiniani.46 Finally, in December he paid a substantial sum (£20.0s.0d.) into the Borromei bank on behalf of Cristofano Cattano, their agent at Southampton, who was a major supplier of pigments.47

During the course of 1438, the turnover in the Borromei account of Raffaello Giustiniani amounted to £1,213.12s.1d., and at the end of the year a credit of £10.0s.5d. was carried forward to the ledger for the following year. Raffaello also maintained a separate joint account with Girolamo Lomellino, with a turnover of a further £100.0s.0d.48 This made him one of the Borromei bank’s more important clients. The ledger entries show that he acted as a conduit for funds being transferred to Bruges by bills of exchange, presumably to pay for goods to export.49 Funds are also shown being transferred from Bruges, mainly to Genoa to other members of the family, as well as to Seville, Barcelona, Avignon, London, and to the papal court, which was then resident in Bologna. There can be little doubt that Raffaello was resident in Bruges as the agent of the Giustiniani family in Genoa and that he traded for them and for himself on the markets in Bruges, Antwerp, and Middelburg. The financial dealings of Raffaello Giustiniani in 1438 offer the most substantial evidence currently available for a member of the family situated in the Burgundian Netherlands during the period when the triptych was commissioned from van Eyck.

A Traveling Altarpiece

This evidence is significant in a broader sense, shifting the focus from the donor as an individual to the more general context for commissioning a work of art in Bruges in the late 1430s. In size and construction, the triptych was ideally suited for a mobile patron, for use in temporary lodgings, such as those occupied by a merchant. As a matter of tradition, Bruges merchants shifted their activities to Antwerp during the annual Pinxstenmarkt, the Whitsun fair, which lasted for six weeks. However, after the uprising in May 1437, the ducal court and city officials evacuated Bruges, and many merchants are thought to have retained temporary residences elsewhere, perhaps until the late spring or summer of 1438.50 Available evidence also suggests that mercantile activities in Bruges were severely disrupted during the Anglo-Burgundian conflict, which reached crisis point in the years after the Peace of Arras in 1435. This has led to theories that the foreign merchant communities stayed away from Bruges altogether until negotiations with the duke encouraged their return.51

Something that would help to support the argument that the Dresden Triptych was a privately owned, portable altarpiece would be evidence of a papal privilege. Recent research by Diana Webb suggests that portable altarpieces became increasingly common from the thirteenth century onward, when more frequent grants for their possession were made by the pope.52 In the ten years of his pontificate (1342–52) Pope Clement VI granted licenses for portable altars to some 150 individuals in England alone.53 A few of the grantees, who included the king and members of the highest nobility (Henry, count and later duke of Lancaster), a knight, a squire, and citizens of London and Lincoln, were also licensed to hear mass at daybreak or to have it celebrated privately in places under interdict. It goes without saying that evidence of a papal privilege to own the Dresden Triptych or other contemporary portable altars could offer a valuable point of reference. Perhaps more digging in the supplications housed in the Vatican Archive could bear fruit, but in lieu of this, it is plausible to consider that a portable altarpiece painted for a member of the Giustiniani family could have been used in temporary lodgings in Middelburg or Antwerp.

If this was the case, and assuming that Jan van Eyck painted this portable altar in his Bruges workshop sometime in 1437, the texts on the frames take on new significance because they appear to be linked to Bruges itself. According to Carol Purtle, the texts suggest a specific relationship with the liturgy of the church of Saint Donatian in Bruges as a spiritual home.54 If the triptych was painted for Michele Giustiniani of Genoa, the texts might be read as a form of nostalgia. If it is associated with Raffaello or another member of the Giustiniani circle resident in Bruges, the texts might well reflect the donor’s efforts to integrate into Bruges society in the manner achieved by the Adornes. Either way, the altarpiece would have provided the donor with a familiar location for his contemplation of the Virgin, wherever he found himself.

Like a Book

Issues of use and practicality in the format and surface treatment of the triptych would have been central to its conception and creation as a portable object. Its book format and the legibility of the Annunciation on the exterior wings have been compared to van Eyck’s Madrid Annunciation (ca. 1437–38) by John Hand, Catherine Metzger, and Ron Spronk.55 They suggested that the undated Madrid diptych was produced soon after the Dresden Annunciation, with small but significant revisions. The shapes of the underdrawn pedestals closely resemble each other, but the bases in the Madrid version were extended over the lip of the lower member of the frame during the painting process, ostensibly to provide a greater sense of spatial perception from a particular vantage point.56

The framing devices chosen by van Eyck also point to the needs of a mobile client, who potentially packed the triptych in a small crate or carrying case for transport within the Burgundian Netherlands or to Genoa. The folding wings would have functioned as a protective barrier: when closed, they would ensure that the red lake garment of the Virgin would not come into contact with a cloth cover or packing material within a chest or crate. Like the draperies in van Eyck’s Lucca Madonna and Van der Paele Madonna, and the under-dress of the Berlin Virgin and Child in a Church, the red-lake-containing paint would have required considerable time to dry. Depending on the precise makeup, thickness, and siccative content of the glaze layers, these could have been dry to the touch within several weeks, but a firm film would take much longer, possibly a month but perhaps as long as a year.57

Furthermore, in order that the Annunciation on the Dresden exterior wings could withstand bumps and movement, the upper and lower moldings of the wing frames for both inner and outer images were constructed in a single piece, with deep recesses on both sides.58 The semi-integral frame could thus bear much more weight and stress. The paint on the exterior frames was apparently damaged while they were fulfilling their original protective function, because in the sixteenth or seventeenth century a faux turtle-shell design, imitating the then-fashionable veneer, replaced the earlier scheme of jaspered paint.59 The book format can thus be thought of as serving an important function, protecting the images within during transport, while the frame would lend additional stability to the panels. Like the jaspered sides and reverse found on van Eyck’s Saint Barbara, the Portrait of Margaret van Eyck and other contemporary works, the jaspering was meant to be seen, but its speckled appearance also camouflaged wear and tear.

Conclusion

The question of whether Raffaello Giustiniani commissioned the Dresden Triptych for Michele Giustiniani, for a member of his circle, or for himself may never be answered satisfactorily: neither the name given in the Borromei ledger, the structure of the triptych, nor its surface treatment offers sufficient information to identify the donor depicted by van Eyck in 1437. The new evidence is perhaps more significant in a larger sense, pointing as it does to the financial dealings of the Giustiniani family, who like other Italian merchants, appear to have shifted their activities to Middelburg and Antwerp between 1437 and 1439. Thus, the evidence in the Borromei ledger, in context with contemporary events, points to circumstances that would have been more challenging for commissioning a work of art from Jan van Eyck than have been previously acknowledged.