Over the past four years an inquiry has been conducted into the painting methods and materials employed by Gerrit Dou on a group of thirteen paintings in the Leiden Collection, New York, that spans the career of the artist. The study incorporates the results of diagnostic imaging by infrared techniques and X-radiography, analysis of selective pigment samples, dendrochronology of the support panels, and microscopic examination of Dou’s paint handling and sequences of application. The study has brought to light numerous revisions by the artist in developing these compositions, some of which shed light on more fundamental issues of meaning in the depictions.

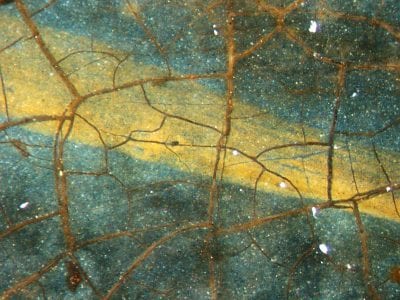

Gerrit Dou (1613–1675), one of the most important seventeenth-century Leiden artists and progenitor of the so-called fijnschilder style, has received considerable attention in the art historical literature since his rediscovery from relative obscurity in the 1960s. However, only a handful of publications discuss the technical aspects of his work and his work method.1 In 1987, Luuk Struick van der Loeff and Karin Groen published their technical research of Dou’s 1658 Young Mother in the Mauritshuis, no doubt one of the masterpieces of Leiden fine painting.2 One of their conclusions was that Dou adjusted the composition by making several changes over a longer period of time, possibly even five years after having started the painting.3 Through microscopic examination and multiple forms of instrumental analysis, Struick and Groen also concluded that Dou achieved the smooth and detailed finish of the Young Mother by applying the finely ground paint in many thin, superimposed layers. This method differed greatly from that of his former teacher Rembrandt, with whom he studied in Leiden between 1628 and ca. 1632.4 Their analyses confirmed, for the first time, Dou’s use of bitumen and its subsequent role in crack formation in the dark passages.

Six years later, in 1993, Eric Jan Sluijter placed Dou’s paint technique in the context of seventeenth-century art theory and criticism, most notably the 1642 art treatise by Philips Angel.5 Sluijter discussed Dou’s extraordinary manner of balancing highly detailed and meticulous renditions with a loose and free handling of the brush. In particular, Sluijter noted Dou’s way of creating a sense of liveliness in an otherwise smooth, enamel-like surface, by applying tiny, parallel brushstrokes, almost like hatchings.6 Friso Lammertse, in 1997, discussed the material aspects of Dou’s 1652 Quack in Rotterdam and his 1663 Self-Portrait in Kansas City, convincingly demonstrating that there were also considerable changes in these paintings, some of which Dou made years after the paintings had initially been completed.7

On the occasion of the Dou exhibition of 2000–2001, Annetje Boersma revisited the Mauritshuis Young Mother and also published findings on Dou’s 1667 Lady at Her Toilet in Rotterdam.8 Boersma reiterated that Dou generated various changes during the paint process of both paintings and that he superimposed multiple thin paint layers. She also mentioned that some of the pigments, especially in the Young Mother, had changed over time, thus providing us with a slightly different image of the paintings than Dou had intended.9 In 2002, Jørgen Wadum published an important article in which he analyzed some of the main characteristics of Dou’s paint technique.10 He noted the interesting contrast between the high level of finish in Dou’s paintings and the large number of changes made during the paint process, concluding that under the smooth upper layers, Dou’s work method, with the numerous changes and broad brushwork, was more Rembrandtesque than we realize.

Thirteen paintings by Dou in the Leiden Collection in New York constitute the largest group of works by the artist in a private collection, and span the full breadth of his career.11 Between 2009 and 2013, the entire group was subjected to technical examination, including three additional paintings, one an early workshop painting attributed to the artist and two considered to be from Dou’s circle.12 The methods of examination include X-radiography, infrared reflectography, microscopic examination of the paint applications, compositional and stratigraphic analysis of selective pigment samples, and, where possible, dendrochronology.13 The goal of this investigation was to broaden our understanding of the artist by building upon the knowledge gained from the studies mentioned above, expanding upon what has been learned by others about the artist’s working methods.

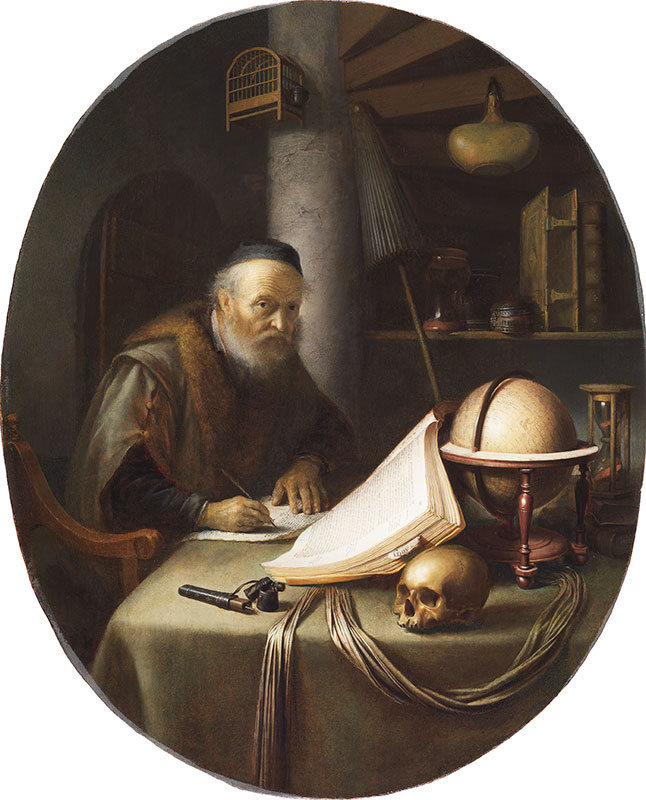

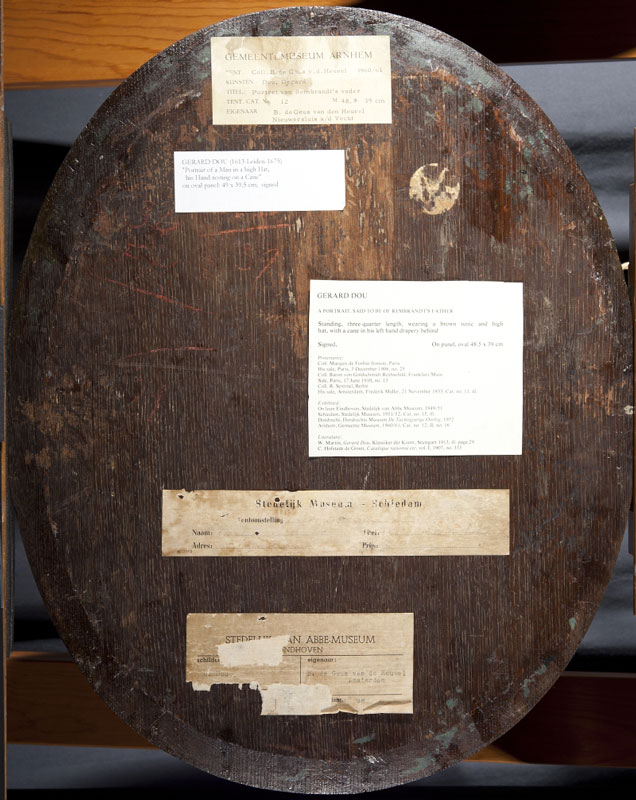

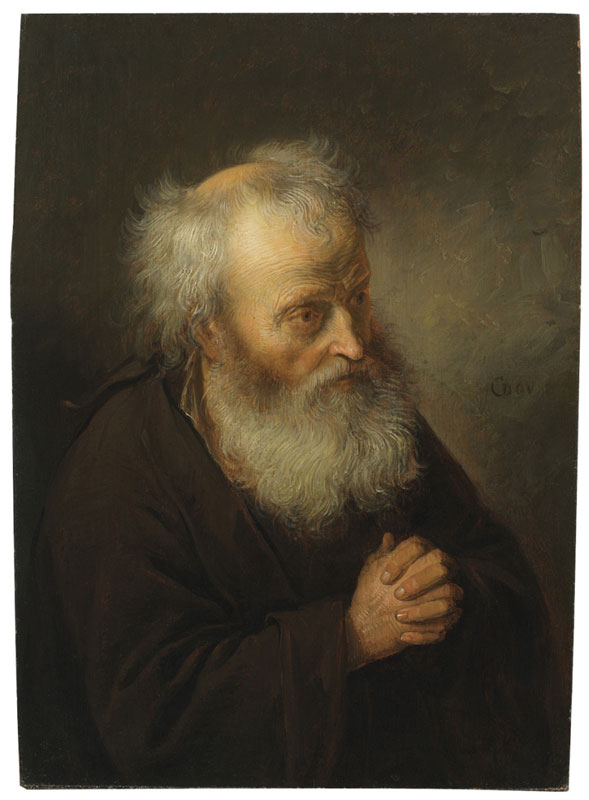

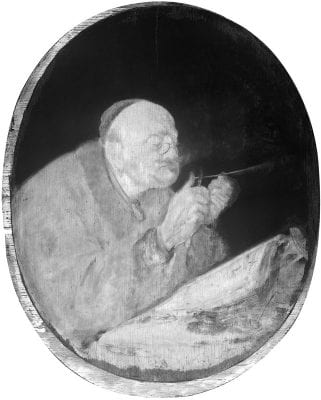

This essay represents a progress report highlighting the most significant findings of the research thus far. It is centered on the group of securely attributed paintings by Dou in the Leiden Collection that were examined during the course of the study: Scholar Sharpening a Quill of ca. 1630–35 (figs. 1a–1b), Scholar Interrupted at His Writing of ca. 1635 (figs. 2a–2b), Portrait of a Young Man with a Hat, ca. 1635 (figs. 3a–3b), Portrait of a Lady in Profile of ca. 1635–40 (figs. 4a–4b), Portrait of a Gentleman with a Walking Stick of ca. 1645 (figs. 5a–5b), Portrait of a Lady with a Music Book of ca. 1640–44 (figs. 6a–6b), Cat Crouching on the Ledge of an Artist’s Atelier, dated 1657 (figs. 7a–7b), Portrait of Dirck van Beresteyn of ca. 1652 (figs. 8a–8b), Young Woman Holding a Parrot of ca. 1660–65 (figs. 9a–9b), Goat in a Landscape of ca. 1660–65 (figs. 10a–10b), Hermit Praying of ca. 1665–70 (figs. 11a–11b), Old Woman at a Niche by Candlelight, dated 1671 (figs. 12a–12b), and Herring Seller and a Boy of ca. 1664 (figs. 13a–13b). In the following, we discuss insights into Dou’s paint technique and present a reconstruction of Dou’s painting methods based on our observations and following the sequence of operations Dou would have followed in his paintings. We start with an overview of Dou’s supports, followed by a discussion of his ground layers, preparatory design and underpainting, choice of pigments, handling of the paint, and compositional and iconographic changes.

Within this study, special focus is given to the two recurring elements in the Dou technical scholarship so far. Firstly, we have looked specifically at Dou’s use of pigments and their discoloration over time for insights into the earlier appearances of the works. Due to the small size of most of the paintings as well as their fully restored states at the time of study, cross sections for stratigraphic analysis were rarely possible in important areas of the compositions. Accordingly, pigment identifications are more numerous from the uppermost layers or more heavily painted areas. Our pigment studies focused particular attention on the artist’s choice of blues and yellows, since many of the pigments in these colors are likely to change over time. Our findings corroborate some prior observations while adding new insights into Dou’s wide choice of pigments and the optical effects achieved between the multiple translucent paint layers. Secondly, like others, we have observed a high frequency of changes in Dou’s paintings in the Leiden Collection. Here, we describe the most significant examples that demonstrate the extent to which Dou, during the very process of painting, would go beyond revisions of a merely compositional nature to explore iconographic elements that were integral to the overall meaning of the work.

It is important to note that this progress report focuses solely on Dou’s technique. Unfortunately it lies beyond the scope of this paper to place Dou in the context of his students and contemporaries, partially because in-depth and systematic technical research has not been carried out on other Leiden fijnschilders. It is our hope that this presentation of the results of our research will provide a basis for future investigation.

The Supports

With the exception of the Portrait of Dirck van Beresteyn, which was executed on a silver-copper alloy, all the paintings by Gerrit Dou in the Leiden Collection were painted on oak panels, the most common wooden support in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. This is not surprising, since the Leiden fijnschilders generally executed their small compositions on panel supports — as opposed to canvas.14 Although most of the oak for paintings in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries came from the Baltic region, the Baltic wood trade declined in the first half of the seventeenth century.15 The repercussions of this decline are reflected by the types of oak panels used by Dou. Most of Dou’s earlier works in the Leiden Collection, for instance his Scholar Interrupted at His Writing of ca. 1635 and his Portrait of a Lady with a Music Book of ca. 1640–44, were executed on Baltic oak (figs. 2b and 6b).16 His later works, however, were painted on oak from other sources, such as his 1664 Herring Seller and a Boy (fig. 13b), the oak for which originated in the Franco-German region.17

Significantly, there are cases in which Dou’s later paintings were executed on Baltic oak, wherein the wood itself was old enough to predate the Baltic wood trade decline. A related, important observation that arose from the dendrochronological analysis of the Dou paintings supports one identified by Annetje Boersma in 2000, namely that Dou frequently used panels taken from trees that were felled considerably before the paintings’ execution date.18 In three of the paintings discussed in this article, Scholar Interrupted at His Writing of ca. 1635 (fig. 2b), the 1657 Cat Crouching on the Ledge of an Artist’s Atelier (fig. 7b), and Goat in a Landscape of ca. 1660–65 (fig. 10b), the youngest measured annual ring of the panel dates to the late sixteenth century.19 In his 1657 Cat Crouching on the Ledge of an Artist’s Atelier, the youngest annual ring of the panel dates as early as 1580, implying that the panel could have been ready for use as early as ca. 1591–97. Ian Tyers noted that this early dating could suggest prior use of the board, for example, for wood paneling.20 For many other panels there is a considerable period of time between the year in which the youngest heartwood ring was formed and the year to which the panel is dated, which again reinforces Boersma’s observation.

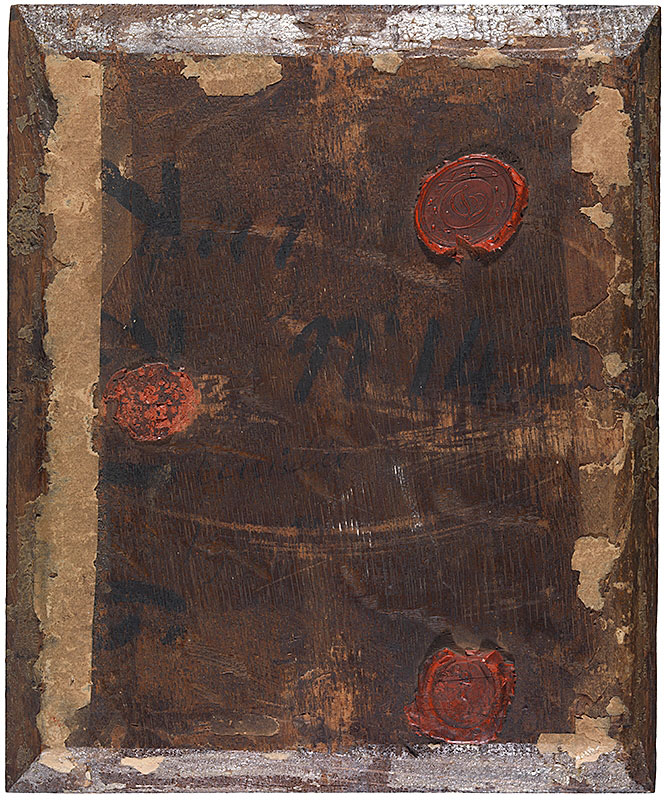

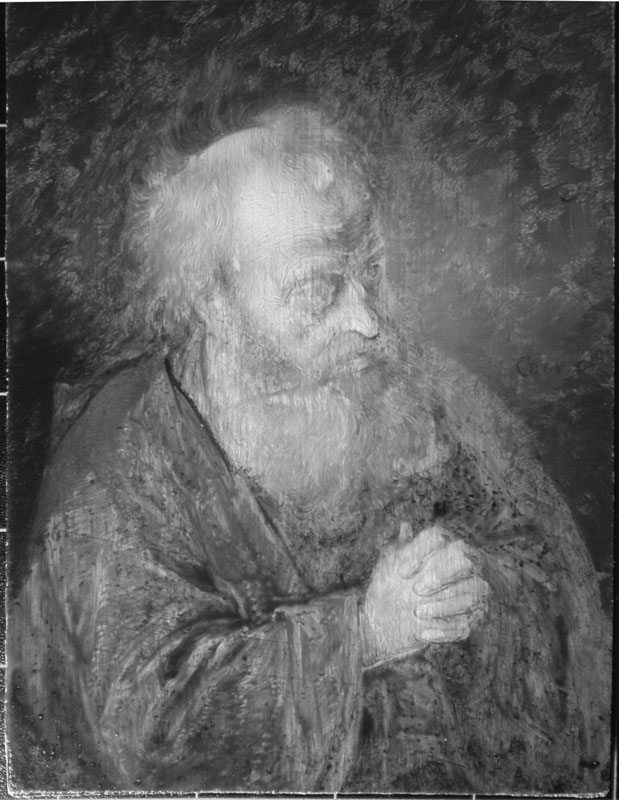

Regardless of the origin and the age of the wood, all timber went through a long processing period from the moment it arrived in the harbor of Amsterdam to the day Dou was able to paint on it. In Dou’s lifetime the wood would probably have been cut and smoothed down in mechanized sawmills.21 Only one painting in the Leiden Collection, the Hermit Praying, appears to have been cut by hand, for the intact reverse contains the irregular grooves presumably created by a handsaw (fig. 11b).

Dou would not have purchased his ready-made panels from the miller directly but from specialist panel makers.22 Panel makers would normally bevel all four edges of the reverses down to a thickness of a few millimeters, most likely to enable a comfortable fitting in their frames.23 The Hermit Praying is an example of a panel that retains the original beveling on all four sides (fig. 11b). Sometimes, however, a panel was only beveled on three sides, because one side was naturally thinner due to the way it had been cut radially from the tree trunk, as exemplified in the panel of Herring Seller and a Boy (fig. 13b).24 Unfortunately, none of the Dou panels in the group contain any panel-maker marks, making it impossible to uncover the panel makers that Dou favored.25

Panels were available to Dou in a range of standard panel sizes, which corresponded with standard frame sizes.26 In 1997, Ernst van de Wetering observed that almost all of Rembrandt’s Leiden panels, many of which were executed during the time that Dou studied with him, can be arranged according to ten clusters of standard sizes.27 In 2001, Christoph Schölzel published a similar list of six standard panel sizes especially encountered among the Leiden fijnschilders, based on the holdings of the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden.28 Although the paintings by Dou in the Leiden Collection fit into several of the categories recorded by Schölzel, the majority fall under the first, smallest category, measuring approximately 26 x 20 cm, including his Scholar Sharpening a Quill, Scholar Interrupted at His Writing, Goat in a Landscape, and Hermit Praying, discussed in this essay.29

The division of the Leiden Collection panels according to these categories of standardized panel sizes leads to two insights. First, the panel sizes are not restricted to any particular period within Dou’s career — he used different panel sizes throughout his life. The second is that Dou’s preferred size, whether by his choice or by that of his patrons, was the smallest, approximately 26 x 20 cm, which, interestingly, corresponds with Schölzel’s findings among the Dou paintings in Dresden.30

One of Dou’s paintings, the Portrait of a Lady in Profile, preserves an unusual format that represents a later configuration. The oval panel with the portrait, measuring 13.3 x 11.3 cm, was set into a larger, rectangular panel, measuring 18.4 x 15.3 cm. The reconfiguration of the panel is visible from the front only, so that the panel itself provides a full encasement for the oval board (figs. 4a–4b). Traditionally, this painting is placed in Dou’s early oeuvre, in ca. 1635–40, which has also more recently been confirmed by historical analysis of the sitter’s costume and jewelry.31 Dendrochronological analysis of the larger, rectangular panel carried out by Ian Tyers, however, has revealed that its youngest annual ring can be dated to 1653, suggesting that it could not have been ready for use until ca. 1664–70.32 It thus seems that the oval portrait was inlaid into the larger panel in the 1660s or 1670s. It is not clear why the painting was adapted to a larger format in this manner, or why this happened approximately two decades after the painting’s execution. In Dou’s oeuvre there are other examples of panels that were later inserted into larger panels, for instance his ca. 1655 Young Lady on a Balcony in the National Gallery in Prague.33

The Portrait of Dirck van Beresteyn is painted on a rare type of metallic support, which is, as far as we are aware, unique among Dou’s works (fig. 8b).34 Paintings that utilize a hammered copper sheet for the support are not unusual in Dutch works of the seventeenth century and span a range of sizes. In some cases the copper has been clad with silver, a step that reduces some forms of adverse interaction between painting and copper support. However, for this portrait Dou used a hammered oval sheet created from an alloy of silver and copper — a fused mixture of the two metals analogous to sterling or coin silver. The use of this more costly material aligns with Dou’s preference for precision and finish and was made less expensive by the tiny size of the painting.35

Ground Layers

After the panel or metal support was fashioned by a specialized craftsman, Dou would have arranged to have it further prepared for painting by a “primer” (primuerder). In Leiden, Dou probably relied on the local frame-maker Dirck de Lorme, who provided the service of priming panels and canvases for local artists up until his death in 1676, when the work was taken over by Leendert van Nes.36 The ground layer was prepared with a mixture of chalk in glue and would have been applied to the support by De Lorme before being brought back to Dou’s studio. Its function was to fill in the crevices of the wood grain and smooth out any irregularity in the surface.

Until now, our knowledge of Dou’s grounds was limited to the study of two mid-career paintings: The Young Mother from 1658 in the Mauritshuis and the Lady at Her Toilet from 1667 in the Boijmans Van Beunigen Museum.37 In both cases, the light-colored ground was found to be very thin. Struik van der Loeff and Groen noted in particular that the ground application of The Young Mother was prevalent in the crevices of the wood grain and inconsistently thick from place to place. In some samples of cross sections taken, the ground was entirely absent, while in other areas, they noted a much thicker chalk ground.38 Our own direct observations confirm that the ground tends to be highly variable among Dou’s paintings, although the irregularity of the ground structure in Scholar Interrupted at His Writing is similar to that of The Young Mother, despite the fact that more than two decades separate them.39 Little is known about the grounds of a wider group of paintings in Leiden during this period, yet one would expect to find the ground composition and its variability to be a widespread occurrence rather than a representative trait unique to Dou.

The upper ground, or first layer of color applied on top of the ground, is what Karel van Mander called the primuersel, or priming, sometimes known by the Italian imprimatura.40 This thin, translucent layer, generally made up of a mixture of chalk, lead white, and earth pigments for toning, is oil based and covers the entire ground, making the ground layer less absorbent, while providing an intermediate tint to the surface. Wadum described this layer in the Dou paintings he examined as being light or buff colored.41 In Scholar Interrupted at His Writing, ca. 1635, the light-colored primuersel is visible through areas of miniscule losses in the scholar’s cloak under a rust-colored, monochrome painted sketch (fig. 14).42 In a painting from three decades later, Goat in a Landscape, a cross section taken from the sky shows an umber-toned primuersel layer that is relatively thin and located between the ground and the grayish-blue undermodeling (figs. 41a, 41b and 41c).43

Preparatory Design and Underpainting

Because no preparatory drawings by Dou survive, it appears that he did not work out his compositions beforehand on paper.44 Dou seems to have sketched his compositions directly onto the panel, or primuersel layer, with line or brushed underdrawings. Wadum listed numerous instances of underdrawings found in Dou’s work that he described as essentially “fragmented,” yet he reproduced very few examples that give a clear indication of their character and appearance. Wadum suggested that Dou must have laid down detailed compositions directly onto the panel in different levels of detail.45

We can assume that Dou executed complete compositional sketches in the preparatory design phase, even though only certain linear areas are visible in infrared imaging. Dou does not seem to have consistently used a carbon-pigmented medium, nor do all of his paintings have visible linear underdrawings.46 Variations in sketch work may be explained by the use of different pigments and different brushes used in the same painting. This variability extends beyond the choice of materials to the character of the sketch itself. While Dou seems to have treated certain areas with careful linear precision, particularly areas of the face, hands, and occasionally outlines of books and other still- life objects, he probably sketched out other areas using different pigment.47 In these areas, we usually see a complex matrix of washy brushstrokes that appear very spontaneous in character. It is possible that this dynamic sketch work overlays, and obscures, more preliminary line drawings, but it is also possible that the brushy sketch work visible in the infrared image constitutes Dou’s initial inlay of the design.

Four paintings in the Leiden Collection contain faint traces of Dou’s line underdrawings, each located in isolated areas.48 In Scholar Sharpening a Quill from ca. 1630–35, there are several thin, yet distinct, contour lines visible around the upper page of the book and on the top ridge of the hourglass (fig. 15). Similarly, a fine sketch in the birdcage hanging on the wall in the background of Scholar Interrupted at His Writing is partially visible in the infrared image, as is the broadly sketched silhouette of the oblong object that represents an earlier compositional idea (fig. 16). In this same painting, faint lines visible through the paint of the scholar’s ear coincide with those seen in the infrared (figs. 17a–17b). In Portrait of a Lady with a Music Book from about 1640–44 (fig. 18) a number of fine lines define the pages of the book on the woman’s lap (fig. 19), as well as the books located on the table at the far right (fig. 20). A later example dated to the second half of the 1660s, Hermit Praying, contains a finely delineated underdrawing in the hermit’s hands, especially in the joints of the folded fingers and fingernails (fig. 21).49

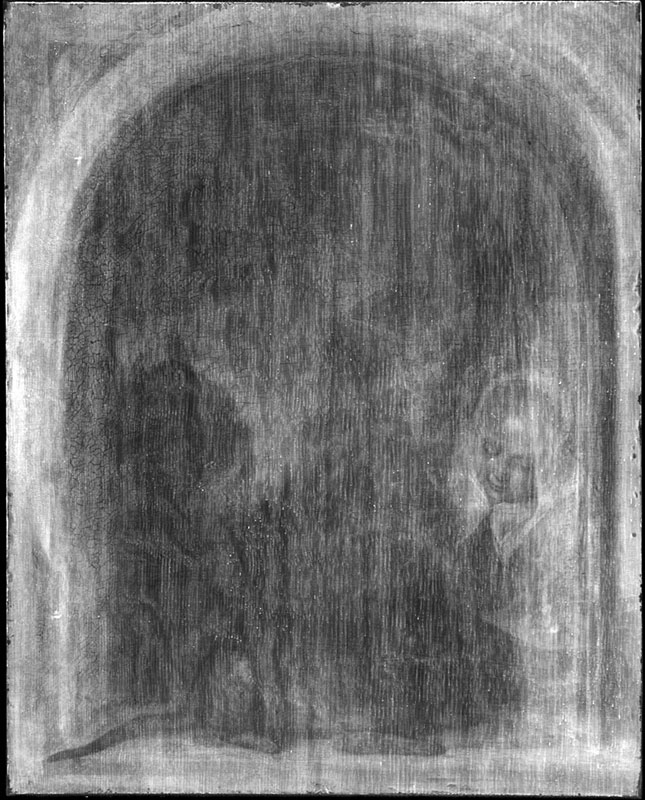

Dou executed broad sketching for most of the compositional elements, including the areas of fabric and dress. In Hermit Praying, one can see much more freely brushed sketch work in the folds of the cloak, particularly in the garment crease of the figure’s proper left arm (fig. 22). This type of broad treatment is seen in Portrait of a Gentleman with a Walking Stick from the early 1640s, in which Dou loosely sketches a more elaborate architectural setting, including an arched doorway in the center of the composition as well as a column and base at the far left, both of which were later omitted in the final composition (figs. 23a–23b). A preliminary, broad-line sketch in the same painting, found below the figure’s proper right collar, may have originally indicated the lapel of his cape (figs. 24a–24b).

This broad sketching appears to have been laid down after the more careful linear drawing. In Portrait of a Lady with a Music Book, the sketch of the woman’s black outer gown overlaps the corner of the finely — and previously — delineated book on her lap (fig. 19). Similarly, in Scholar Sharpening a Quill, we can see a single bold brushstroke in dark pigment that appears to be a subsequent reinforcement of the rim of the top of the book, adjacent its linear drawing (fig. 15). Yet, other brushwork, due to its free execution style and spontaneous character, suggests an exploratory phase of the design, as seen in Scholar Interrupted at His Writing. There, thick and cursory brush strokes in darker pigment are visible in the infrared image along the garments of the scholar’s proper right arm (fig. 25). Other freely and broadly painted strokes seen at the edge of the table suggest that Dou may have originally conceived of the table as round rather than rectangular.

It is clear, however, that at times the sketch work was executed in place of careful line drawings. In Scholar Sharpening a Quill, much of this early phase brushwork is visible in the infrared image (fig. 26). The scarf tied around the scholar’s neck appears in the preliminary sketch as a simpler tie (figs. 27a–27b), while his proper right cuff was sketched in broader strokes with darker pigment, suggesting that Dou initially had in mind a heavier or different fabric from what he painted in the final version. In this preliminary stage of the composition, it is evident that the loosely executed brushwork begins to give volume to form by indicating the play of light and shadow.

After the “invention” phase of the composition, the second stage involved the execution of the first paint layer in muted colors, sometimes referred to as “dead coloring.”50 The purpose of the dead coloring phase was to begin to give volume and body to form while differentiating the various planes and outlining silhouettes in various tones of paint that would later be built up with color. Like his teacher Rembrandt, who sometimes executed his initial sketch directly on the ground with a broad brush while laying in the first tonal color, we can assume that Dou, under his tutelage, would have learned to do the same in the early stages of the composition.51 Wadum, in fact, characterized this stage in Dou’s painting as one of “vigorous undermodeling.”52

The brushwork visible in the infrared image of Portrait of a Lady with a Music Book, exemplifies the extent of Dou’s handling of the dead coloring, ranging from smooth and uniform to sketchy and energetic (fig. 18). The area of the woman’s outer black dress, appears as vigorously modeled in rich pigments, while the area surrounding and defining the woman’s head, which was left unpainted in reserve, is more uniform. In the area of the figure’s garment in Scholar Sharpening a Quill, the dead coloring is a highly saturated, brown-violet mixture, composed mostly of a red lake pigment, iron earth, charcoal, and Kassel earth and smoothly applied (figs. 28a, 28b and 28c).53 In the infrared, we see that Dou has distributed a layer across the figure’s entire vestment, outlining the overall silhouette with paint. Dou sketched in the figure’s cuff and fur collar as tonally distinct, indicating that the opacity and depth of pigmentation would vary from place to place (fig. 26). The infrared also shows that Dou painted the dead coloring of the background around the entire silhouette of the figure, extending around the book and hourglass. Some of this darker layer of the background remains visible through the upper layers of the old man’s proper left-hand knuckles, where Dou later revised the position of his hand to the right (figs. 27a–27b).

Oftentimes, the dead coloring layer made use of less costly pigments, since its function was to establish a general underlying hue and degree of reflectivity that the upper, translucent paint layers would build upon. A cross section taken from the sky of Goat in a Landscape reveals that the dead coloring forms an intermediary layer of blue-gray that the upper, more costly ultramarine layer very thinly covers (figs. 41a–41b).54 In a stripped-state photo of the painting taken during conservation treatment, some of this gray undermodeling in the sky was visible in striations along the wood grain before retouching (fig. 40).

While the opportunity to examine all thirteen paintings in the Leiden Collection using both infrared imaging and X-radiography has provided considerable insight into Dou’s underpainting and design phase, it is difficult to determine any clear trends that would allow us to show how Dou’s technique evolved over his long career. For example, in comparing the group of four niche paintings that spans his middle to late career, Cat Crouching on the Ledge of an Artist’s Atelier, 1657; Young Woman Holding a Parrot, ca. 1660–-65; Old Woman at a Niche by Candlelight, 1671, and Herring Seller and a Boy, ca. 1664, we see a variety in the underpainting and the approach to the preparatory sketch. While the Old Woman at a Niche by Candlelight of 1671 appears to have been executed quickly in the initial design phase with much broader, brushy sketch work (fig. 29), neither the Herring Seller and a Boy (fig. 30) nor the Young Woman Holding a Parrot (fig. 31) contain any brushy sketch work in the preliminary phase. They appear to have been carefully planned and straightforwardly executed, without any visible compositional changes during the painting process. The infrared of one final niche scene, Cat Crouching on the Ledge of an Artist’s Atelier, provides striking evidence of careful planning and meticulous execution in the early stages of painting, while revealing numerous compositional changes during the painting process that must have occurred over a longer period of time (fig. 71a); these are discussed in greater detail, below.

Selectivity and Precision in Dou’s Choice of Pigments

The investigation of Dou’s palette in the works in the Leiden Collection was constrained by the small size of most of the paintings and their fully restored states at the time of study.55 Dou’s choices for blues and yellows have been the subject of particular interest since they offer insight into issues of cost and selection between synthetic and mineral pigments. These colors also offer information about the formulation of violets and greens of which they are often a component. The roles that they play in Dou’s sometimes complex, translucent layering are important aspects of the artist’s craft that can be fully understood only through their identification. Perhaps most importantly, blues such as smalt, ultramarine, and indigo are frequently affected by fading or color change. The identification of pigment alteration is essential to the recognition of how, and in what degree, the paintings differ today from their appearance almost four centuries ago.

Among these paintings of the Leiden Collection there is at least one example of every blue pigment known to have been in use during the period, with the exception of blue verditer. The same can be said for Dou’s use of inorganic yellows, though the identification of organic colorants in yellow “lake” pigments was not possible, leaving distinctions among organic yellows less clear.56 While our study encompasses a significant group of works securely attributed to Dou, it is nevertheless difficult to discern trends in his pigment choices. There are several reasons for this. We have found that even with the number of paintings to which we have access, they are sufficiently varied in the requirements of their diverse subject matter (niche paintings, portraits, genre scenes, interior, exterior, nighttime, and daytime scenes) that it would be extremely speculative to project trends onto this disparate evidence. Directly comparable passages in the paintings are few.

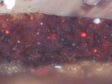

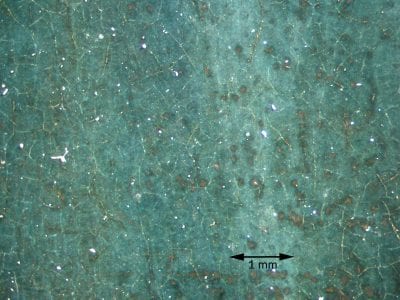

At one end of the spectrum of Dou’s choice of color, there is an example in the Portrait of Dirck van Beresteyn (fig. 8a) in which a single blue pigment, smalt, is used alone with white, or modified by earth colors and bone black, for all shades of blue in the painting. The condition of the layer is good apart from minute, localized eruptions of lead–fatty acid soaps that are commonly encountered in Dutch seventeenth-century works (fig. 32).57 While smalt has been widely observed to undergo a loss of color saturation and graying in the works of many artists, the pigment in this example is in good condition, indicating that the color observed today is not far removed from Dou’s original intent (figs. 33 and 34a–34b)58

At the other end of Dou’s spectrum, we can observe blues of great complexity in both blending and layering. Testing has revealed that pigment alteration is certain to have impacted the color and interplay of optical effects in some of these constructions. However, the cumulative shift of the observed color is difficult to extrapolate due to the many optical interactions of the multilayered passages. In some cases, the nuances of colors that were originally intended remain very hard to interpret in spite of the detailed knowledge we have obtained about the various pigments and their precise distributions among the layers.

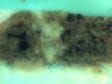

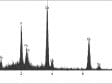

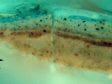

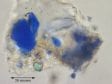

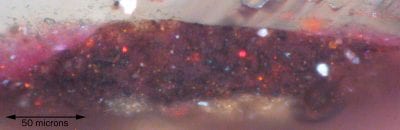

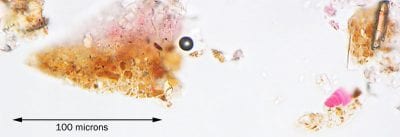

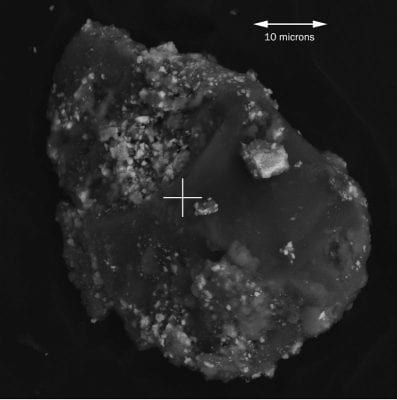

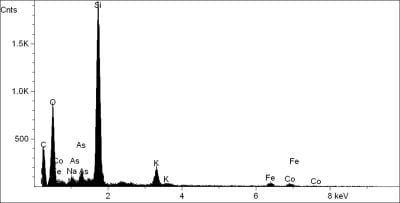

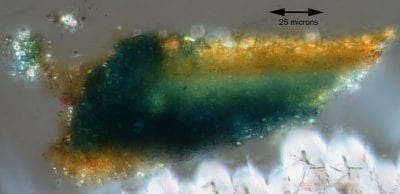

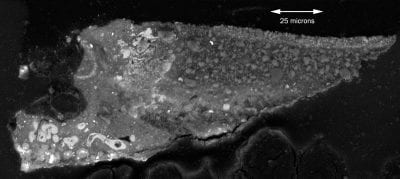

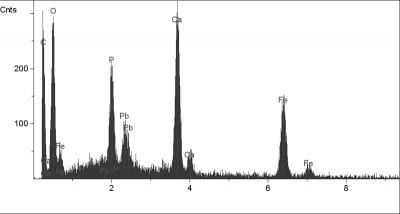

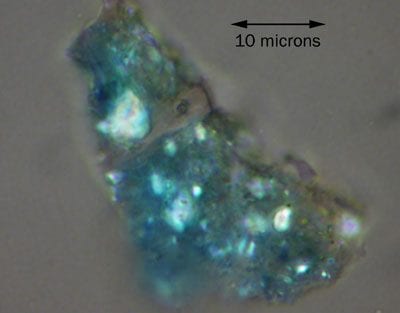

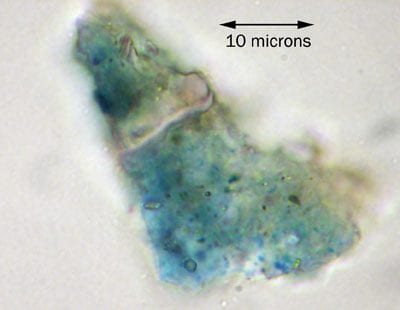

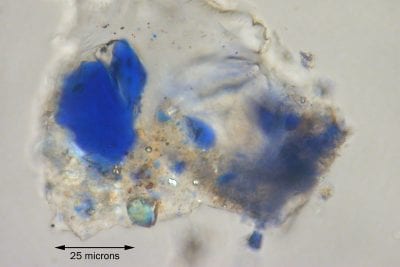

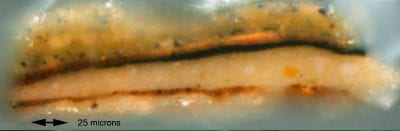

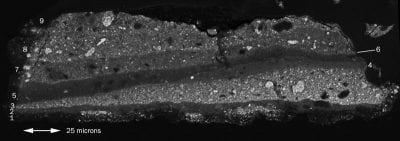

Scholar Interrupted at His Writing serves as an example of this complexity by combining the use of the blue pigments vivianite, indigo, and azurite in translucent paint layers (fig. 2a). Dou has made use of the relatively uncommon blue pigment vivianite in the upper layer depicting the shadow of the book where the scarf emerges below it on the table (fig. 35).59 Both the tablecloth and the scarf lying on it, which today have an accentuated yellow hue, contain pigment mixtures with large proportions of blue (figs. 36a, 36b and 36c). We can expect that a distinction in color originally existed between the two cloths. However, since both the azurite used in the tablecloth and the vivianite used in the scarf are brilliant blues, this distinction may have entailed other components, including the influence of underlying colors and the use of glazes that may not have survived cleaning over the centuries. While some degree of yellow in the light reflected from the book onto the scarf below was certainly intended, its intensity has increased due to the yellowing of vivianite in the top layer of the scarf. Based upon its identification by electron microscopy and elemental analysis, the yellowness of the layer, seen in a thin section (fig. 36a), has been confirmed to be due to the alteration of vivianite (figs. 37 and 38a–38b).60 Calcium carbonate is also present in the top layer and could have served as the base for a yellow lake pigment that would now be difficult to discern in cross section from the discolored vivianite. However, no evidence for the presence of a yellow lake could be found via polarized light microscopy of the dispersed pigment. Likewise, the study of fracture sections in SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy), in which morphological differences among particles of similar composition are often more readily distinguishable, did not reveal any distinctions between the calcium carbonate of this top layer and that employed in other locations. Therefore, no evidence could be found for the presence of an organic yellow along with the vivianite.

Another blue pigment, indigo, was used in a lower layer of the tablecloth, which strongly influences the colors of the translucent layers above. Its tendency to obscure the distinctions among the lower layers was mitigated in our tests by the use of ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy (figs. 36a–36b) and polarized light microscopy (figs. 39a–39b). In addition, the oil medium in all three blues can be expected to have undergone its own yellowing. For that reason, the shift toward green is not unique to the discolored vivianite layer and will have impacted the azurite and indigo as well, affecting the appearance of both cloths.

Indigo is used here in a mixture that contains calcite and gypsum with virtually no lead white. This ensured that it would be strongly colored but low in reflectivity, thereby contributing to a multilayered sequence in which all strata are translucent. This practice contrasts with the frequently encountered use of an indigo in combination with lead white as a reflective light blue underlayer beneath other blues. Indigo often has its own fading and discoloration problems but, in this case, it is well preserved.61 Because of the multiplicity of blue pigments that have undergone various changes in color, as well as the complex optical interactions Dou intended among his superimposed translucent paint applications, it is difficult to interpret how the two cloths in Scholar Interrupted at His Writing would have originally appeared.

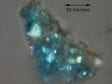

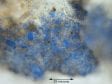

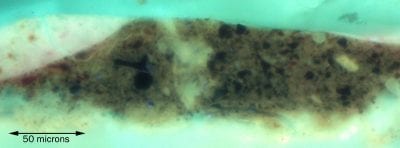

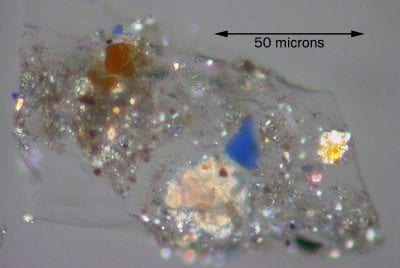

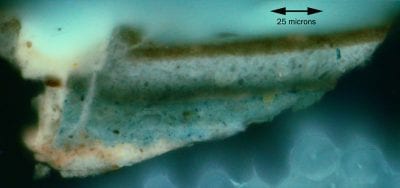

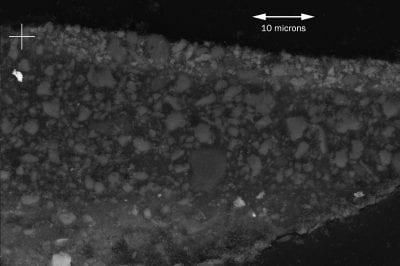

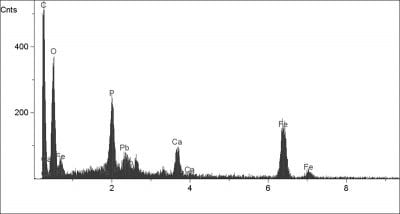

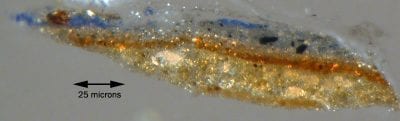

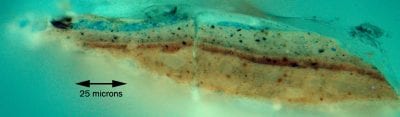

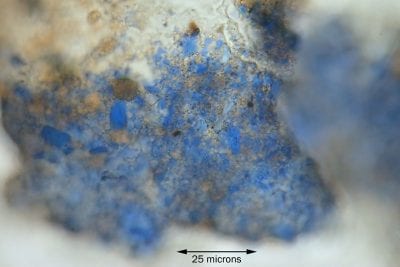

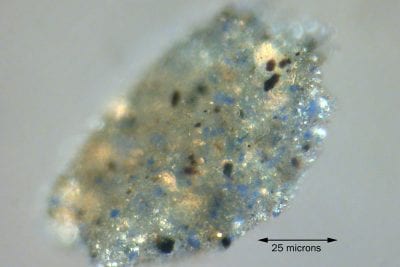

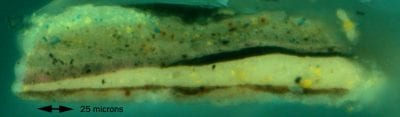

Goat in a Landscape, an unusual subject for the artist, offers a third example of Dou’s use of blue (fig. 10a). All blues in this painting consist of natural ultramarine of very high quality, a costly material relative to alternative blue pigments of the time.62 No smalt, indigo, vivianite, azurite, or blue verditer were found, even for the underlayers.63 The ultramarine has been employed in different degrees of coarseness and remains vibrantly blue, with no sign of fading or discoloration of the pigment (figs. 41a, 41b and 41c and 42a–42b). Gray that is visible in the sky (fig. 40) has been determined through our testing to be due to exposure of an underlayer resulting from wear of the top layer, rather than to discoloration of the blue pigment. A layer of gray-blue beneath the worn top layer of ultramarine in the sky is visible in the cross section, and the ultramarine in both layers remains vibrantly blue (figs. 41a, 41b and 41c and fig. 43).

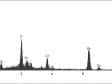

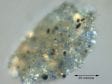

The large burdock plant in the lower left corner, which also consists of ultramarine, appears as unusually blue rather than green today, a condition that might be presumed to be the result of the deterioration of a yellow component in the painted structure (fig. 44). However, few remnants of yellow pigment were found in a cross section within the uppermost layer of the foliage. The sample was intentionally taken from a complex, multilayered area and contains a lower, yellow layer that appears unrelated to the final position of the leaf (figs. 45a, 45b, 45c and 45d). The blue pigment ultramarine is abundant in the upper, damaged layer, while the much smaller proportion of yellow lake particles is only revealed by fluorescence during UV microscopy (fig. 45c).64 The greater concentration of the yellow lake among the more opaque pigments of the lower layers (fig. 45b–45c) suggests that these deeper particles could not, by themselves, have reflected sufficient yellow color through the overlying blue to be the sole basis for achieving the green foliage.65 This implies that the original green color of the leaves was probably augmented by a final yellow glaze that has not survived. This sample serves as a useful example of the imperative of employing all the methods illustrated in figures 45a, 45b, 45c and 45d, since each reveals an aspect of the stratigraphy or of the pigmentation that is not apparent in the others.

The Handling of Paint

In our discussion of Dou’s choice of pigments, we described how Dou’s distinctive layering in the Scholar Interrupted at His Writing and Goat in a Landscape contributed to the final blended appearance of color on the surface. Dou used the underlayers in a similar fashion to achieve depth of color and three-dimensionality in the delicate areas of hands and faces. To create half-tones, he underpainted shadows with a dark color over which he applied translucent flesh tones. He used this technique in the face of the old woman in the Herring Seller and a Boy, for example, where he painted pink and paler flesh-tone highlights over a dark-bluish undermodeling along the side of her nose extending down the front of the folds of her cheek to the side of her jaw (fig. 46).

In portraying the overlapping of objects in space, Dou followed a logical sequence of building up his compositions by working in sequential planes, from the rear to the front. This order of painting from the background to the foreground must have been one of the methods Dou learned in Rembrandt’s workshop, for a number of Rembrandt’s early Leiden paintings also follow this order.66 In Dou’s case, an essential aspect of this practice involved leaving certain foreground elements unpainted in reserve by outlining their silhouette with the adjacent paint of the background, to be painted in at a later stage.67 An example from Dou’s later career, Young Woman Holding a Parrot from the early 1660s, demonstrates this order in the visually complex area of the birdcage, where several planes of depth overlap to be seen through the front and rear spokes of the cage (fig. 47). From microscopic examination of the paint layers, it is clear that Dou built up the composition from the rear wall to the front of the cage. The overlapping paint layers correspond with the building up of the composition, as though moving from the background toward the foreground in space.68

One of the more characteristic surface features of Dou’s painting technique is his hatching brushwork, consisting of tight, parallel lines in the upper layers of paint. Scholars have noted this distinctive brushwork in a wide range of paintings throughout Dou’s career.69 In Scholar Sharpening a Quill, the hatching is confined to the highlights of the scholar’s right hand (fig. 48), while the technique is also seen enlivening the texture of aging skin along the temple and inside rim of the old man’s nose in the face of Hermit Praying (fig. 49 and fig. 50). In Young Woman Holding a Parrot this hatching describes the coarse texture of woolen twill in the curtain (fig. 51). This technique relates to Dou’s occasional use of materials to make “stamped” impressions of textures in the paint, while here it is freely done with the brush.70 In most cases, Dou uses this hatch work to soften highlights and invigorate the texture, yet the same brushwork is also frequently visible in areas of deep shadow.

In Scholar Interrupted at His Writing, Dou’s brushwork operates at times on a strikingly miniscule scale. While he carefully indicated that the book on the table is open to page “61,” both the printed text of the page and the script on the folio under his quill are deliberately illegible (fig. 52). Here, Dou suggested the character of block-printed letters with measured strokes, while contrasting them with the looser handwritten script on the folio, formed with infinitesimal brushstrokes of paint (figs. 53a–53b). In the darker recess of the shelf in the background, Dou unexpectedly included distinctive, yet faint, capital letters on a jar, “. . . ALVES,” showing the label partially obscured by an overlapping glass container (fig. 54).71

Dou’s masterful range of brushwork is particularly evident in the freely rendered curly wisps of hair that fall across the hairlines of his male and female figures. The sheer number of individual strokes that together create the appearance of a mass of plush, wavy hair is quite extraordinary (fig. 55). Dou undoubtedly used varying thicknesses of brushes to create these visual effects, some evidently executed with a brush consisting of just a few bristles (fig. 56). In a Portrait of a Lady in Profile, Dou indicated single strands of hair on the woman’s temple as purely translucent, in tones of adjacent flesh color rather than as pigmented hair color (fig. 57). Dou’s concept of hair as lucid texture reflecting whatever color lies behind it is also evident in his painting of the woman’s fur collar. Here he dragged his brush back and forth over the whites of the woman’s blouse (fig. 58).

Compositional and Iconographic Changes

Our examination of paintings in the Leiden Collection reveals that Dou made compositional changes during virtually all phases in the painting process. Some of these occurred in the early stages of painting among the lower strata, whereas other adjustments can be observed with the naked eye in the upper layers of paint. These changes provide insight into Dou’s painting practice and indicate that a significant degree of trial and adjustment with compositional elements was integral to his work method, as scholars have also remarked in the past.

A common type of change involves adjustments to the main figure in a composition. In Goat in a Landscape, for example, the X-radiograph indicates that Dou changed the direction of the goat’s head from profile to frontal (figs. 59a–59b). Similar adjustments were made in a number of single figure portraits in which Dou shifted the figure to one side relative to the picture plane. This is particularly evident in Portrait of a Lady with a Music Book, in which changes along the figure’s face, right arm, and shoulder seen in the X-radiograph indicate that Dou initially positioned the sitter centrally beneath the painted arch and later shifted her to the right by about 3/8 inch, possibly when he modified the arched-top format (fig. 60a–60b).72 A more subtle alteration is observed with the naked eye in Portrait of a Lady in Profile, in which the sitter’s profile, from the hairline down to her nose, was shifted slightly to the left during the painting stage (fig. 61).

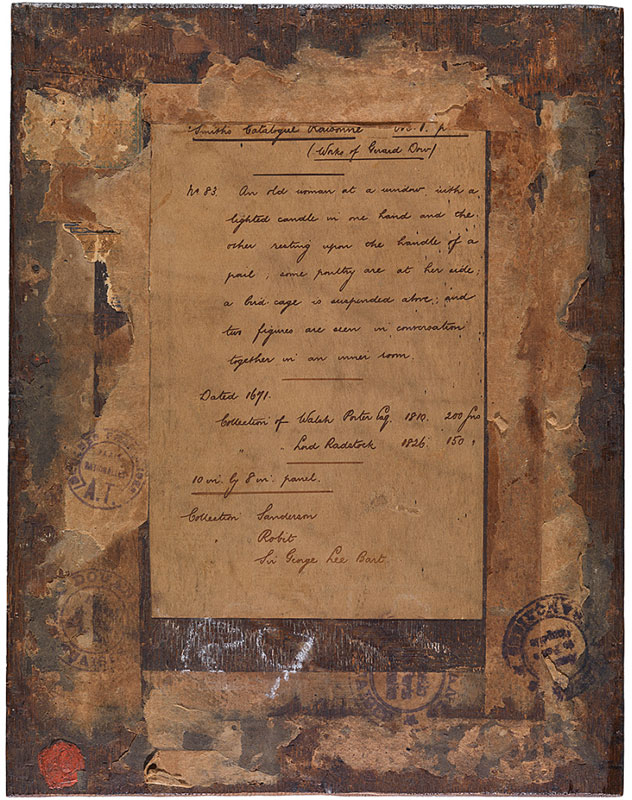

Dou made a series of more complex compositional changes in Old Woman at a Niche by Candlelight (fig. 12a). While Dou positioned the woman so that her candlestick breaks the picture plane and provides the painting’s visual focus, its precise location was established fairly late in the paint process. Initially, Dou intended an oil lamp to stand on the window ledge, where the dead bird’s head rests in the final arrangement, and portrayed it as held by the old woman’s proper left hand. An X-radiograph indicates the position of the initial lamp flame (fig. 62a–62b), while a stripped-state photo taken during restoration reveals the original position of the old lady’s left hand, grasping the upper base of an oil lamp, where the artist later painted a basket (figs. 63a–63b).73 Similar oil lamps are depicted in paintings from the period, which show a metal oil receptacle with a flame emitting from its side (figs. 64a–64b).74 It is not clear what meaning, if any, Dou intended with the change from an oil lamp to a candle. The highlights on the proper left side of the woman’s face and the shadow on the near side of her face seem to have been defined by the original position of the oil lamp facing her, indicating that the modification occurred at a relatively late stage in the painting’s execution. In the infrared image, much of the preparatory sketch work and dead coloring correspond with the earlier position of the oil lamp in the distribution of light and shadow, particularly along the ledge as well as the right and left sides of the niche (fig. 29).

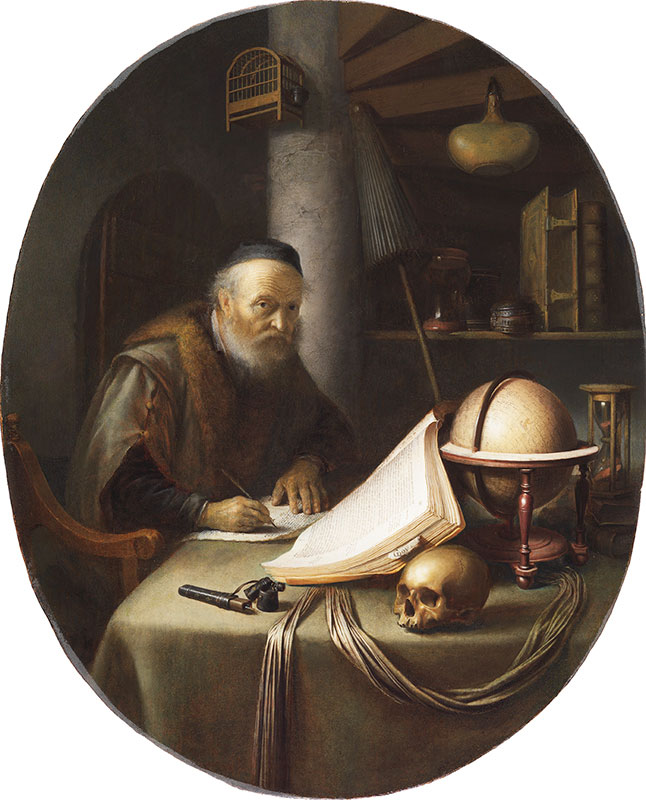

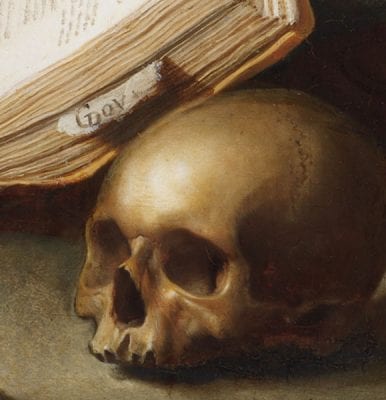

Two paintings stand out as fascinating examples of more radical changes Dou made that affected the meaning of the iconography. An early work from about 1635, Scholar Interrupted at His Writing, is one of the most accomplished and finely executed works in the artist’s early mature style (fig. 2a).75 The painting depicts an elderly scholar seated at a desk in the midst of writing, with his pen quill paused on paper as he looks up at the viewer. An X-radiograph reveals that Dou originally planned for an artist’s easel to be a prominent element in the composition in the upper right quadrant (figs. 65a–65b).76 This compositional configuration recalls paintings attributed to the young Dou from the late 1620s and early 1630s such as Artist at His Easel, in the Leiden Collection (fig. 66) or Man Writing by an Easel, in a private collection.77 The iconography explores the concept of the learned artist or the parallel between the artist and the scholar, a theme that Dou continued to develop even after he omitted the easel.

In the place of the easel in the central background of Scholar Interrupted at His Writing, Dou added a shelf with various small jars and books and a Japanese parasol leaning against the column.78 In an earlier stage in the composition, Dou seems to have intended other objects on the table in the foreground, possibly a lute or other books, but later painted a skull (fig. 25).79 Later in the painting stage, Dou added an hourglass, a symbol of transience, and included a slip of paper extending from the side of the book.80 Together these motifs establish, in a manner different from the obvious motif of the easel alone, an important parallel between the artist and scholar. One can assume that Dou’s elder scholar is exploring questions concerning the transience of life in his own work and that he remains mindful that the wisdom and knowledge passed along through books will supersede the temporal limitations of his life. As a clever equivalent, Dou referenced the vanitas topos of art surpassing life’s brevity by inserting his signature, “GDou,” on a tattered piece of paper on the side of the book, adjacent to the skull (fig. 67).81

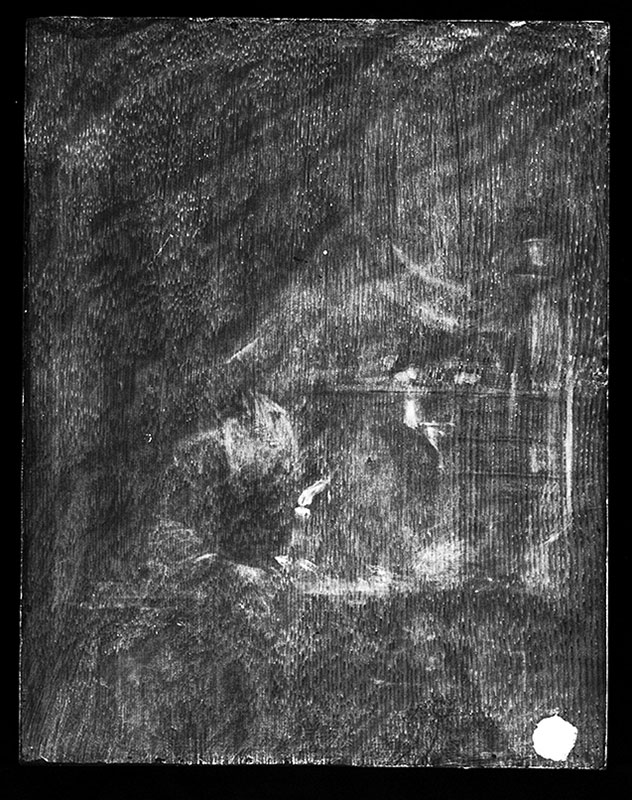

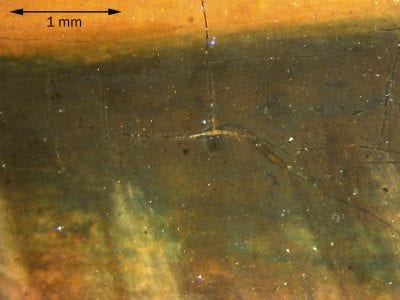

A second painting that underwent significant changes in iconography during the painting stage is Cat Crouching on the Ledge of an Artist’s Atelier, painted at the height of Dou’s career in 1657 (fig. 7a). Dou’s unique depiction of a cat, a curtain draped open to view a dimly lit interior, and an artist painting at his easel was not the artist’s initial concept for this work. An X-radiograph reveals that before he added the curtain on the right, Dou painted a young woman leaning forward over the ledge (figs. 68a–68b). Both the IR photograph and X-radiograph show that Dou also painted out a small rectangular shape in the lower right corner of the windowsill that appears to have been a mousetrap (fig. 69). The object has a diagonal lever at the top and is strikingly similar to other mousetraps in paintings of the period, such as that in Dominicus van Tol’s Boy with a Mousetrap, from ca. 1660–64, also in the Leiden Collection (figs. 70a–70b).82

While it is possible that the young woman was part of an earlier, unrelated composition, in Dou’s other interior scenes featuring a mousetrap he included a figure who discovers, or presents, the trap with surprise, which may explain the woman’s original role.83 The depiction of a cat watching a mousetrap was well known in the emblematic tradition, but the combination became popular in fijnschilder genre painting of the 1670s and later.84 Because the image of a cat and mousetrap had such clear associations with love’s seductive entrapment, it appears that Dou intended to allude to the theme in the earlier version of the composition.

In addition to these significant changes, the X-radiograph also partially reveals the face of a masonry arch at the upper left and right corners of the niche (figs. 68a–68b). These fragmented arched lines appear to extend beyond the current format and suggest that the panel was once taller and wider on the right side. Significantly, the panel’s reverse is only beveled on the left side, indicating that the panel was cut or thinned down on the other three sides (figs. 72a–72b).85 Other remnants of an earlier composition are visible to varying degrees in both the X-radiograph and IR image, including the silhouette of a side-draped curtain, hanging from the upper left and gathered about two-thirds up the left side of the painting, as well as a circular shape at the center left that is reminiscent of a globe (figs. 71a–71b).86

It remains unclear which of these elements was part of a preliminary stage of the final design and which may represent an earlier, or altogether unrelated, composition. However, Dou’s rendering of the cat’s fur in the manner described above, over an area left in reserve where only a thin ground and the panel itself remain slightly visible through the strokes, provides clear evidence that the cat was planned from the earliest stage and the sill painted around him. In the expanded initial format, the young woman, cat, and mousetrap would have formed a plausible compositional focus, centered to the right within a larger niche frame. In this earlier configuration, the placement of the curtain on the left would have complemented the group offset on the right. Perhaps when Dou decided to omit the mousetrap and young woman, he reduced the size of the composition in order to center the cat within a smaller architectural niche. This would explain why the panel was cut down, why the curtain was painted over the young woman on the right, and why the architectural niche was depicted as a much more prominent feature in the final version, with a broader surrounding frame.

In the final composition, Dou made the unusual choice of depicting the cat in the niche isolated by itself.87 Eric Jan Sluijter has shown that the cat appears as an attribute of sight in late sixteenth-century prints.88 Dou seems to have expressly intended this significance and portrayed the animal as fully engaging its sense of sight, as it intently focuses on something beyond the picture plane.89 The striking illusionism of the curtain, a reference to the story of Parrhasius’s famous curtain, and the scene of an artist painting at his easel in the background further reinforce the primacy of sight in artistic terms, thereby reiterating sight as the basis for the illusionism of the painting itself.

Conclusion

The opportunity to carry out numerous technical comparisons among the Leiden Collection works by Gerrit Dou has significantly expanded what we know of Dou’s painting materials and process. Our study has confirmed several important findings made by other scholars in recent years, including Dou’s frequent use of well-seasoned panels, his reliance on numerous translucent paint layers for subtle optical effects, and his tendency to make compositional changes throughout the process of painting.

Our research builds on this understanding in three important ways. Microscopic examination of the paint layers has provided a new degree of certainty regarding the structure of paint applications and, thereby, a more detailed understanding of Dou’s sequence of painting steps. Secondly, laboratory study of paint samples has added significantly to the very limited information previously available on Dou’s choices of pigments. Consequently, we now have a clearer understanding of the roles that he chose for individual pigments and the interrelations of their behavior in Dou’s multilayered constructions. The identification of Dou’s pigments and their position within the sequence of paint layers has also provided a more precise view of the original appearance of these passages and allowed us to infer the roles of materials that have been lost through prior cleaning or pigment fading.

Finally, X-radiography and IR imaging have revealed changes that shed light on Dou’s thought processes. We have learned the extent to which Dou revised his compositions, sometimes making quite radical changes that materially affected the overall meaning. The examination of the underlayers of paint through this technology has also aided our understanding of Dou’s preparatory design work and technique. Dou, of course, adopted the method of sketching directly onto the ground and working up the composition from his teacher Rembrandt — a practice that, for both artists, invariably led to revisions or changes as the idea for each work developed during the painting process. In addition to what we learned from this technical study about Dou’s painting process and method, we also have glimpsed what he must have learned from his master. Similarly, as research is carried out on the technique of Dou’s pupils, we can expect that this will, in turn, shed additional light on what they learned from Dou.