Although the painter withdrew to a Devotio Moderna-associated monastery at the end of his life, this article questions whether Devotio Moderna texts are the right lens through which to view Hugo van der Goes’s Berlin Nativity, proposing instead to examine the painting side-by-side with texts produced in Bruges for the urban lay community to which most of Hugo’s patrons belonged.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (fig. 1) by Hugo van der Goes has been perceived by art historians as an act of artistic implosion.1 In an early version of this argument, Erwin Panofsky drew on the sensational biography of the artist; we know that Hugo suffered from a psychological breakdown in the late 1470s and tried to commit suicide. The Adoration and the Death of the Virgin (fig. 2) are probably the artist’s last works, painted after his suicide attempt and shortly before his death in 1482.2

Panofsky writes that the space in these panels “has ceased to be rationalizable, let alone metrical,” asserting that the off-kilter atmosphere was symptomatic of their creator’s unbalanced mind.3 Subsequent authors took a less romantic route, rejecting the idea that the paintings’ compositions reveal insanity and focusing instead on how Hugo’s belief system shaped them.4 Hugo’s suicide attempt followed his withdrawal from a career as a successful painter in Ghent to a cloister outside of Brussels that adhered to the tenets of Devotio Moderna, or the New Devotion movement.5 Recently, the implosion argument has been recast to contend that the appearance of Hugo’s late paintings derives from the ascetic character of the movement’s spirituality. The New Devotion’s founder, Geert Grote, advocated an aniconic ideal of spirituality, exhorting followers to transcend images in their devotion. In this telling, the failure of the image is reframed as spiritually edifying, in line with New Devotional principles, rather than as an unconscious production of the artist’s mental illness6. In both explanations (mental illness and the New Devotion), the interpretative weight rests on the painter, not on the people for whom he produced the painting, and Hugo was working in a patron-driven environment.

For Panofsky, the painting’s strangely fragmented pictorial space is the most prominent aspect of its conceptual and formal collapse. The disjointedness of the image can be largely attributed to the Adoration’s eccentric format, which provides a stage for a remarkably hectic depiction of the adoration. The image is a panorama, seen as if through a wide-angled lens, with the action at the margins as accentuated as that at the center. The scene takes place within a shed, whose roof and front are cropped from view. The sides of the building are dramatically splayed, receding from the wide edges of the panel to a narrow far wall, and the image’s rather high horizon creates a steeply sloping ground plane that orients the action forward and outward. The composition is vertically segmented into alternating dark and light bands, and its figures are clustered in episodic groups, leading around a semicircle to the Virgin’s glowing face.

It is the eccentric format which first indicates that we should look beyond Hugo’s immediate circumstances to understand the painting. At 97 centimeters high and 245 centimeters broad, its short, wide dimensions are unusual for an Early Netherlandish panel painting, leading to suggestions that it served as a predella or an antependium.7 However, two scorch marks along the bottom edge of the panel indicate that candles were placed in front of it, making it likely that the painting was used an altarpiece. For this reason, it is likely that the peculiar dimensions were specified by the patron in the commission of the painting, not for aesthetic reasons but because the Adoration was designed to replace an older image of the same size.8

Further, last year’s restoration of the Adoration by Beatrix Graf offers a new perspective on not only the chaotic composition but also the dour colors and flattened contours of its central figures,9 which had previously led some art historians to perceive the image as being ascetic or self-critical (compare fig. 1 and fig. 3).10 Absent the dirt and varnish removed by Graf, the middle ground figures project a more fully realized presence as three-dimensional bodies and narrative actors. Two light sources illuminate the events of the darkened shed: an even, uniform light that seems to originate behind the picture plane and a brighter, directed light that shines into the stable through its door. The intensity of this second light source, which casts the entering shepherds into relief, has become much more evident after cleaning. Also apparent after cleaning is a rosy blush on Mary’s glowing face and the small, rounded limbs of the tiny Christ Child, articulated against the whitened cloth on which he lies. Most notably, the cleaning has revealed a newly heightened color scheme. Mary’s gown is a crisp, sapphire blue. The warm, saturated red and orange of Joseph’s garb glows against the bright, cool tones of the kneeling angels’ robes. The first hint of daylight is visible on the horizon behind the shepherds, and the expanse of dawn sky is an astoundingly deep and vivid shade of blue, creating an almost surreal “day-for-night” effect.11 The more intense colors shift the emotional tone of the image from severe and remote to joyful, and the greater level of detail now visible in the depiction of the Holy Family heightens the intensity of the viewing experience.

Although the composition itself has not changed, the newly brightened, more cheerful palette makes the internally coherent logic of the picture more evident. The burst of light that follows the shepherds into the shed heightens the force of their rush into the space, just as the steady, sacred glow of the Holy Family binds them together in stillness. Mary’s radiance and the hieratic frontality of her pose make her the image’s center of gravity and a stark contrast to the whirlpool of action that swirls around her.12 She is portrayed as timeless and still, surrounded by the instability of what Alfred Acres has dubbed “small time,” a mode of representing the physical world that concentrates on “the flow of moments.”13 At left, one musician is in the midst of a clap, the other has his lips to his recorder.

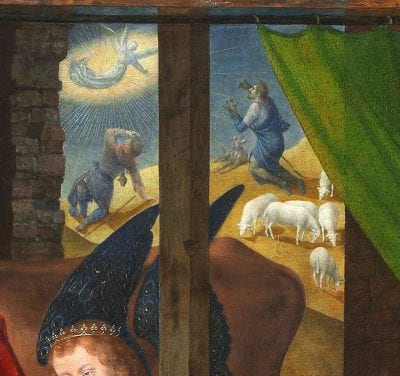

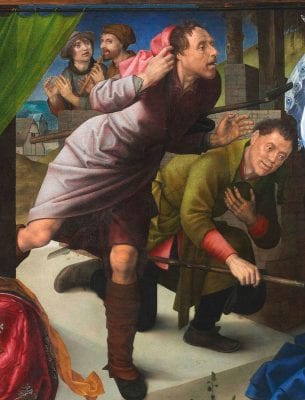

One shepherd gallops through the door of the shed, while another sinks into a bow (fig. 4). Each of the angels who surround the Holy Family tilts its head at a slightly different angle in a cascade of nearly identical angel faces, a configuration that looks like the serial representation of a single head in motion (fig. 5). The figures gaze upon on a vulnerable Christ Child, presented tipped-up in a manger, the foreshortened sides of which echo the flared walls of the shed. The child looks out at the viewer with a tranquil expression, but his body is not calm. His limbs squirm awkwardly; his left leg and right arm are bent, his little toes tensed and his small fists balled. To the far right, seen through the window of the shed, is the annunciation to the shepherds, an event that takes place several hours before the visit to the Christ Child but is nevertheless represented with the same sense of urgency as the action in the middle ground (fig. 6). One shepherd has been knocked over by the force of the revelation. He grasps his head with one hand, either shielding his eyes or expressing his astonishment. His other hand reaches for the ground to steady himself.

The episodes in the middle- and background of the image belong to the narrative of the adoration of the shepherds, an event that is singular in its historical and spiritual importance as the moment when Christ was revealed to the world (Luke, 2:8–20), and they are portrayed with a fitting combination of seemingly unchoreographed gestures and consummately iconic poses. The Gospel of Luke describes the announcement of the birth of a Savior made to the shepherds by an angel of the Lord, who tells them that they will find him lying in a manger in the city of David. The shepherds go to Bethlehem “with haste,” where they find Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus. The image emphasizes the hurried arrival mentioned by Luke, using a vocabulary of spontaneous human movement; whereas the perfectly composed Virgin is an iconic image that can only belong to the history-changing event of the Nativity, the musician’s clapping could happen anywhere at any time. The represented distance between his hands leads to contemplation of the moments before, when they were separated and the moments after, when they will come together again.14 Likewise, we can anticipate the moments following in the gesture of the left-most shepherd, who is in the process of removing his hood, or the left leg of the Christ Child, seemingly in mid-kick. The middle- and background of the image are pointedly in flux.

In the foreground, this “flow of moments” runs up against a barrier. Two large figures, usually identified as prophets, stand like sentries at the edge of the picture plane.15 Portrayed in half-length, emerging from the picture’s lower border, they are clearly separated from the rest of the image. Instead, the men perform as intermediaries between the viewer and the depicted narrative. The prophet on the left twists around, preoccupied by the scene in the middle ground, while the prophet on the right looks at the viewer, gesturing for him or her to approach the painting. Together, they draw back a set of trompe l’oeil curtains, the rings of which are painted onto an actual rod that protrudes from the surface of the frame. The presence of the curtains could be a metapictorial comment on painterly skill, perhaps recalling the painted curtain Parrhasius employed in his contest with Zeuxis.16 But the opening of curtains, the act of revelation frozen in progress, is also a commentary on, and a contrast with, the momentariness emphasized in the depiction behind them. Seen from a different perspective, the extension of the curtain rod into real space vouches for the “reality” of the image as a whole, but the internal framing provided by the prophet figures establishes the middle ground as belonging to the pictorial realm. The composition of the Adoration is a puzzle, a construction so ornately complex that some art historians have fallen back on the implosion argument to account for its appearance. The juxtaposition of spatial planes and temporal realities, vacillating between near and far, momentary and eternal, is at odds with the normative notion of perspectival representation implied in Panofsky’s comment that the space of the image “has ceased to be rationalizable, let alone metrical.”17 Rather than being comprehensible at first glance, the scene must be unpacked, step-by-step, by its viewers. How do we historically contextualize such an image? The texts of the New Devotion seem to offer a solution to this problem by providing a historical anchor. The writings of Geert Grote appear to be prescriptively explicit; they lay out a historically verified set of instructions for viewing that encourages transcendence of the sensual world and, by implication, of the illusionism used to depict it. The difference between this unworldly medieval mindset and our current image-saturated worldview makes the texts of New Devotion reassuringly strange; the idea of a self-critical image is so counter-intuitive, it must be true. Yet, this may be a trap laid by our own unconscious prejudices as twenty-first–century art historians. Painting that deconstructs its own techniques of representation actually does have precedents in modern art that are familiar enough to instinctively convince us; medium awareness and critique belong to a post-Clement Greenberg understanding of painting, including the work of artists from Jasper Johns to Gerhard Richter.

In the following article, I will argue that despite the appeal of the proposition, it is not in fact historically plausible to connect large Early Netherlandish panel paintings with a program of image skepticism. Unfortunately, we may not be able to recover a set of historical texts that tells us exactly how people were supposed to look at fifteenth-century Netherlandish paintings. These texts may have never existed. Instead, if we want to know what people valued in an art work like Hugo’s, we can approach the question by looking at the kind of interpretative techniques that the painting demands and finding texts that require similar skills. As it so happens, there are such texts, written in the literary circles of late fifteenth-century Bruges, a context much closer to Hugo’s patrons and viewers than the world of the New Devotion, which draw on analogous interpretive skills. In particular, a corpus of religious poems by the rhetorician Anthonis de Roovere exhibits a similar kind of aesthetic complexity and riddle-like structure as the Adoration, and in the case of one particular poem, the Lof van Maria (Praise of Mary [RW F 8 vo]), handles similar spiritual topics. I will make a formal comparison between painting and poem in order to point to the type of religious and aesthetic experience pursued, and presumably enjoyed, by their shared audience, the elite of Bruges. The Lof does not offer us the meaning of the Adoration so much as it broadens our field of reference for the cosmopolitan milieu of late fifteenth-century Bruges, a city with no outposts of the New Devotion.18 A close reading of the poem also gives further evidence of what may have constituted a successful artwork in Bruges – a classification that, I contend, transcended the boundary between poetry and painting in this context. The fact that the artworks did share a historical audience grounds the formal comparison between image and text in a real, social world and shifts the weight of meaning from speculation about the artist’s personal motivation to the milieu in which the image was used and understood. At stake in my use of social and formal analogy as a hermeneutic approach is not just the meaning of one picture or even the applicability of the ideas of one movement to painting, but the question of how much interpretative weight we art historians should give to different pieces of historical evidence, including religious texts, as well as social relationships, political circumstances, devotional practices, artistic patronage and, of course, the appearance of a painting itself.

New Devotional Image Theory

To date, Bernhard Ridderbos has made the most compelling case for the importance of New Devotional image theory in the late work of Hugo van der Goes, arguing that there is a spiritual meaning behind Hugo’s play with varying levels of illusionism.19 For most of his career, Hugo was a profoundly ambitious painter who attempted to rival the grandeur and dazzling illusionism of the Van Eycks’ Adoration of the Lamb, but his withdrawal to a monastery has traditionally indicated to scholars that he had a change of heart. For Ridderbos, the late style of the Adoration and the Death of the Virgin manifests the artist’s renunciation of youthful aspirations and his adoption of the belief system of the New Devotion, which encouraged the believer to transcend the visual image and contemplate God as abstraction. According to Ridderbos, the Adoration of the Shepherds bears witness to Hugo’s attempt to deal with the dilemma that ultimately drove him to break down: the difficulty of reconciling his craft with the aniconic ideals of his religion. The image, in other words, is pedagogically constructed to encourage its viewers to rise above its use.20

The framework for this argument is taken from Geert Grote’s A Treatise on Four Classes of Subjects Suitable for Meditation: A Sermon on the Lord’s Nativity. The text, which describes Grote’s ideal of personal religious practice, outlines a meditational program that begins with concrete images but moves beyond them to contemplation of the abstract.21 The images in question are mental images, projections of the imagination and their sensual associations (such as those of color and sound) that keep a person grounded in the particularity of sense experience. Whereas Grote concedes that corporeal forms and figures are initially necessary to impart wisdom to our “childish minds,” the believer should work to move beyond them.22 He writes, “The more a person is able to withdraw himself from such images and to persist in this abstraction and to place his hope and love in these abstract things, the more truly and purely – short of a full understanding of things – he meditates upon the birth, life, and death of Christ and upon the Holy Scripture, and the more nearly he approaches the eternal.”23This idea of ascent from the particular to the abstract was widespread in medieval theology; Grote cites Saint Augustine, Pseudo-Dionysius, Bernard of Clairvaux, and Saint Bonaventure to support his model of religious devotion.24

Grote’s sermon is the product of considerable erudition and genuine passion; the Paris-educated son of a wealthy merchant from the city of Deventer in the present-day Netherlands, Grote was a reformer in the model of Saints Bernard and Francis. In the late fourteenth century, he embarked on a campaign of preaching, calling on the Church to eradicate decadent practices and return to the values of the apostolic church and the humble cultivation of virtue. To that end, he renounced his income and turned his home into a hospice for poor women.25 Although the original context of the sermon is not known, it is likely, considering its philosophical bent, that it was composed in Latin.26 In this, the Sermon on the Lord’s Nativity marks a departure from Grote’s normal mode of proselytization. The majority of his sermons were preached to his lay audiences in the vernacular. One such sermon, transmitted in Middle Dutch, exhorts the noncloistered audience to cultivate simple virtues like marital fidelity and honesty in business transactions.27

The intellectualism of the Sermon on the Lord’s Nativity makes it both atypical of New Devotional texts and an interesting source for art historians; the sermon voices the opinion of a “high cultural” tradition of theologians, an elevated discourse whose intellectual sophistication accords to the visual sophistication of Early Netherlandish paintings like the Adoration.28 And in its frequent references to “images,” the sermon seems to provide a kind of how-to manual for image devotion. However, there are reasons to question the sermon’s usefulness, both intrinsic and extrinsic to the text. First, we should consider whether a treatise on meditation composed before the widespread use of oil paint can really be applied to fifteenth-century paintings.29 In medieval usage, the word imago was used to refer a number of concepts, not just sculptures and paintings, and in the context of the sermon, it clearly describes mental images.30 Second, and more importantly, large paintings like the Adoration were commissioned objects, meaning that the maker of the image would not have had free reign to express his personal beliefs in the painting. No matter how deeply affected Hugo was by the ideals of the New Devotion, the altarpiece was not willed into being solely by the beliefs of its maker. Instead, if the theme of the image was indeed aniconic, it was so at the behest or approval of the person or persons who paid for it.31 The patron or patrons may not have known Grote’s Sermon specifically, but if they experienced the painting as Ridderbos describes, they must have shared Hugo’s and Grote’s desire to transcend images. In order to gauge the influence of this sermon and the theological ideas promoted by it, we have to try to imagine how and in what form it was received by the public, and we have to try to determine what ideological baggage it carried with it. In other words, what kind of cultural or social currency did the ideas of the New Devotion have in the world at large? And would they have been likely to make their way into paint?

The New Devotion as Historical Phenomenon: The Outlines of the Movement

There are two major reasons to treat cautiously claims of the New Devotion having a direct influence on the wider public in the early modern Low Countries and Germany. First, the religious principles promoted by the movement were largely conventional (including its advocacy of devotion to Mary, meditation on the life and death of Christ, and the importance of the sacraments) and therefore undistinguishable from the mainstream.32 Rather than strong theological differences, what set the New Devotion apart in the late medieval urban sphere was the kind of life led by its semireligious practitioners. They lived at a physical and spiritual remove from the world around them, and this distance is the second reason why untangling the influence of New Devotional ideas is so difficult. In order to trace the paths of transmission for New Devotional ideas, such as aniconism, that diverged from the commonplace, I will start by describing the scope of the movement’s mission within the Church, including their production and reproduction of texts, and then discuss how these texts resonated with the literary culture of the outside world.

The New Devotion movement was made up of two basic components, monastic and semireligious; early in its history, the monastic wing took on a superior position in order to protect the movement from accusations of nonconformity.33 The Rooklooster, where Hugo became a lay brother, belonged to this superior, monastic wing of the New Devotion, which had its center in the Windesheim Congregation near Zwolle in the northeastern Netherlands.34 The semireligious wing grew directly out of the community of laywomen that Grote founded during his lifetime; it quickly expanded to include members of both sexes, becoming what are now called the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life.35 The Brothers and Sisters were gathered in gender-segregated houses, often located in urban centers, with the goal of pursuing spiritual lives dedicated to prayer, self-examination, and manual labor.36 These men and women did not profess ecclesiastically approved vows or wear a habit.37 Nevertheless, their way of life was even more strongly patterned on monastic withdrawal than their semireligious forebears, the Beguines,38 in that they were required to give up personal property (“Common Life” refers to their de facto vow of poverty).39

Over the course of the fifteenth century, outposts of the New Devotion sprang up throughout the Netherlands, including houses in Ghent, Brussels, and Leuven, but its presence was mostly concentrated along the IJssel and Rhine rivers in what is today the eastern Netherlands and western Germany.40 Like other monastic groups that began as reform movements, such as the Franciscans, the brothers were quickly assimilated into, and given a role to play in, the Church structure. Rather than preach like the Franciscans, however, they ran Latin schools for young clerics, which had the stated goal of recruiting novices for the canons regular of the Windesheim monasteries.41

The Brothers of the Common Life also produced books, but their production was largely in Latin and aimed at other religious communities.42 The house in Brussels, for instance, ran a scriptorium and a printing press in the last decades of the fifteenth century, with most of its works intended for an ecclesiastical audience. They printed breviaries for Carmelites and Cistercians, classics such as the writings of Augustine, Bernard, and Bonaventure, more recent texts such as those by Jean Gerson, Denis the Carthusian, and Arnold Geilhoven, a polemic against Islam by Juan de Torquemada, a book of hours, and letters of indulgence – all in Latin.43

Moreover, a good number of the books they produced were intended neither for the larger world nor even for the larger Church. According to research by Thomas Kock, the brothers and canons copied and translated books by hand as an inwardly directed religious exercise, and these copied books were by and large meant to contribute to the spiritual formation of the writer and the library of his community.44 Some New Devotional writers did produce original material for use by their own community. Certain tracts originally written in Latin but published in the vernacular, like the Imitation of Christ by the canon regular Thomas à Kempis, would go on to become enormously popular with the general public, but it seems that they were not originally intended to be widely circulated. Only printed in 1472, the Imitation of Christ seems to have been written or compiled around 1420 for the brothers at the house of canons regular outside of Zwolle.45 Another example of a much copied text is the very popular Spiritual Ascensions by Gerard Zerbolt of Zutphen, which was translated into Middle Dutch and Middle High German and had thirteen print editions between 1483/86 and 1500. Like the Imitation of Christ, the Spiritual Ascensions seems to have been intended for the community; surviving copies can be traced primarily to houses of the New Devout and reformed monastic institutions.46 What this suggests is that the ideas found in New Devotional texts may have had importance for Hugo van der Goes, but these texts were not aimed at the segment of the urban population that I will argue was the primary audience of his large paintings.

The Valence and Prevalence of the Vernacular in the Fifteenth-Century Netherlands

The New Devotion’s association with texts in the vernacular has given the movement a misleading reputation as a forerunner of the Reformation, but these acts of translation and the use of Middle Dutch did not put the practitioners of the New Devotion ahead of their time. Beginning in the fourteenth century, the vernacular came into widespread use in the Low Countries, in both civil and religious arenas.47 Bruges, in particular, was home to a community of writers composing aestheticized texts – rhyming prayers, songs, and poems – in Middle Dutch, which are today preserved in works like the late fourteenth-century Gruuthuse Manuscript (Dutch Royal Library, The Hague). In a way, the Gruuthuse rhyming prayers are symptomatic of the Bruges literary scene as it would develop in the following century. Written using sophisticated poetic forms and an inventive vernacular vocabulary, the works were just as much poems as prayers. Not only did they foreshadow a corpus of rhyming prayers written in Bruges in the fifteenth century, the Gruuthuse rhyming prayers themselves reappear in three surviving, richly decorated manuscripts, commissioned by wealthy and devout residents of Bruges.48

In other words, the New Devotion’s interest in the vernacular is best understood as exemplary of a wider phenomenon in the fifteenth-century Netherlands rather than extraordinary. Grote’s sermon on the Nativity offers us a clear explanation for the general turn toward the vernacular in religious contexts. He writes,

When a learned man . . . hears something sacred expressed in his mother tongue, he seems to conceive in his mind something new or fresh by way of that mother tongue, first impressed on his mind when he was still a boy ignorant of all letters; indeed it seems newer and fresher than if the same thing were said to him in the accustomed Latin way to which his lettered mind would normally turn.49

As a theologian, Grote encouraged the transcendence of the word almost as strongly as that of the visual image, but he also understood the draw of everyday speech. According to Grote, an idea expressed in the vernacular is potentially more compelling in addition to being more accessible. The use of the mother tongue initiates a shift in register, bringing the reader back to the unmediated experience of childhood and offering a fresh, unaffected take on conventional practices.

One of the reasons why Bernhard Ridderbos’s attempt to read Hugo’s Adoration through Grote’s sermon has been persuasive is that it acknowledges the painting’s own shifts in register and the degree to which the composition needs to be worked through by the viewer. The image represents familiar scenes and motifs of the revelation of Christ to the shepherds, but the narrative is unfolded in an unexpected, stutter-stop fashion. Time is broken into illusionistic layers, beginning with the Old Testament prophets, proceeding to the main event of Christ in the manger, and ending with a previous moment in the narrative – the angel’s appearance to the shepherds. Meanwhile in the central vignette, the shepherds, represented mid-gallop, are juxtaposed with the calm stasis of the Holy Family.

However, as has become especially apparent after the cleaning of the Adoration, there is a mismatch between the sermon and the image. For Grote, the material force of the vernacular – its concrete power in the lives of the people who spoke it – was a stepping stone for the devoted on the way to the immaterial transcendent. It is the verbal counterpart of the corporeal forms and figures required to impart knowledge to our “childish minds.” On the one hand, the projection of this attitude onto Hugo’s painting discounts the sheer beauty of the painting. On the other, the pairing of sermon and painting asks us to dismiss the sophistication and intelligence required to work through the layers of the image as simply baby-steps toward a more adult spirituality.

Rather than attributing the complexity of the Adoration to a desire to undermine illusionism itself, I see it as a vote of confidence in the viewer. Unpacking this idiosyncratic staging of the subject requires sustained attention and a willingness to play along with the image’s eccentricity; in trusting the viewer with the responsibility of working through its spatialized treatment of time, the Adoration imputes a high level of interpretative capability to him or her. The visual ingenuity of certain Early Netherlandish painters, such as Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, and Hugo van der Goes, has been the topic of much art-historical scholarship in recent decades, but, as Bret Rothstein has pointed out, the attendant sophistication of the viewer is rarely acknowledged: “we spill so much scholarly ink over developing authorial self-consciousness that we risk missing the fact that such details presume the attention of a similarly clever audience. (The game is not worth playing that offers no opponent.)”50

If we look at the painting through the lens of its intended viewers, rather than the religious bent of its artist, we see that the Adoration was constructed in the expectation of a worthy opponent. Instead of seeing the painting as a didactic tool, we might understand it as a riddle, an occasion for play, with the viewer invited to participate in a process of interpretation that does not end with the image’s collapse. And so in finding a point of reference for how this process may have unfolded, Hugo’s religious convictions are less at issue than the viewer’s aesthetic capabilities and tastes. The urban Netherlands in general, and Bruges in particular, was home to a class of worthy opponents, who were willing to pay for the privilege of solving the riddle. Early Netherlandish paintings like the Adoration belonged to a larger culture of complexity in the international trading city, where wealth and a cosmopolitan outlook provided fertile ground for luxury goods as well as an appreciation for complication – in artistic forms other than painting. The same people who enjoyed unraveling the images of Van Eyck, Memling, and Hugo, were among the audience for a certain kind of rederijker (rhetorician) poetry, written in the vernacular.

An Elite Network and Modes of Reception

According to Anne Laure van Bruaene, rederijkerskamers (chambers of rhetoric) were among the institutions that generated enthusiasm for artistic innovation – visual, literary, and musical –in Bruges; these chambers were one of the elements in an elite network (which also included religious confraternities and tournament societies) that supported these arts.51The first rederijkerskamer in Bruges, the Chamber of the Holy Spirit, was founded in 1428 and had its first recorded public performance in 1442 on the high profile location of the Burg, in front of the Bruges city hall. The Holy Spirit counted wealthy craftsmen among its members, many of whom occupied prestigious positions in the political and economic spheres of the city.52 Most of the members of the chamber were probably not writers themselves,53 but the participation of the nonwriting members in the organization means that they would have been the natural audience, and potential patrons, of active writers such as Anthonis de Roovere. (A mason by trade, De Roovere was probably a member of the chamber and possibly even the son of one of the Holy Spirit’s founders, Jan de Roovere.)54Although the compositions that emerged from the Chamber of the Holy Spirit were written in the local variant of Middle Dutch, they were far from provincial. The poets of Bruges, De Roovere in particular, experimented with French-language poetic forms, such as the ballade, that were the favorites of Burgundian court rhetoricians.55

The rederijkers were active in the urban public sphere, composing plays to be performed for religious processions and the joyous entries of visitors of state. Here, as in the city’s network of elite organizations, there was a great overlap between the literary and artistic cultures. Painters were members of the city’s rederijkerkamers – most notably Lodewijck Halyncbrood, one of the founders of the Chamber of the Holy Spirit.56 And in Ghent, where Hugo served as dean of the painters’ guild, there is even more evidence of the active role played by visual artists in the city’s performance culture.57 Hugo, himself, made cloth paintings for festive events in addition to paintings on panel. He was among the army of artisans who traveled to Bruges to help with the decorations for the wedding of Duke Charles the Bold in 1468, and he painted figures to be displayed along the streets of Ghent for the duke’s entries into the city in 1469 and 1472.58 The prophet figures could well have been inspired, as Mark Trowbridge argued, by theatrical prophet characters, who mediated between the audience and the scene presented, such as in the plays performed at the triumphal entries of Philip the Good into Ghent in 1440 and 1458.59Elisabeth Dhanens suggests that Hugo actually knew De Roovere personally and that the floral imagery in the Adoration of the Shepherds may somehow relate to the floral symbolism used by Anthonis de Roovere in several of his odes to the Virgin Mary.60

The connections between Anthonis de Roovere and Hugo van der Goes went above and beyond mere personal acquaintance; the two artists were at the center of urban society. As active participants in the festive culture of urban Flanders, they both enjoyed good connections to ducal power as well as to the Bruges elite.61 In 1466, Charles secured a pension for De Roovere from the city authorities. In July of 1468, Charles celebrated his wedding in Bruges, and De Roovere supervised the staging of the plays that welcomed the duke to the city on behalf of the municipal authorities. (Paid by the court, Hugo also participated in the pageantry, making decorations for the wedding banquet).62De Roovere wrote a great number of texts for public events in the city, including a play for the feast day of the confraternity of Our Lady of Snow, a eulogy for Duke Charles and the Ode to the Holy Sacrament, which was publicly displayed.63 For his part, Hugo was one of the most successful painters of his generation, with a list of prominent patrons and admirers. His retreat to a monastery apparently did not end his successful career or dampen his fame. The same source that describes Hugo’s breakdown, a section of the chronicle of Rooklooster written by the canon regular Gaspar Ofhuys, also reports that the painter had many distinguished visitors, including the future Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I.64 Their work on similar projects, their shared social milieus, and the greater overlap of painters and rederijkers in the Low Countries, suggests that reading Hugo’s picture side by side with one of De Roovere’s poems might prove particularly valuable.

A Side-by-Side Reading

In contrast to Dhanens, I do not think that a poem by De Roovere served as direct inspiration for the Adoration, rather I will try to demonstrate that their similar themes and shared aesthetic strategies reflect a similarly elite intellectual context. I have chosen for a side-by-side reading De Roovere’s poem Lof van Maria (RW F 8 vo), because it is typical of the sophisticated vernacular poetry for which fifteenth-century Bruges was known. Like the Adoration, the Lof is a riddle that requires untangling on the part of its audience; the experience of reading and understanding the Adoration and the Lof was no doubt as much fun as it was spiritually profound. This poem therefore does not explain the Adoration the way a sermon might, but instead points us toward a mode of reception. The comparable themes of the compositions, I argue, revolve around the tension between the eternal and the present – or to put it another way, Grote’s abstract and the particular – and this produces a similar choreography of reception. Rather than pushing away from sense experience toward the abstract as Grote recommends, Hugo’s altarpiece and De Roovere’s poetry play one off of the other, highlighting moments of specificity by setting them into a stable framework.

The plurality of De Roovere’s preserved output is composed of Marian rhyming prayers, based on popular Latin prayers and antiphons, and many are more like interpretations than translations, with intensely elaborate structures. Most of the Marian compositions are paraphrases or reworkings of the ubiquitous texts of Marian devotion (the Ave Maria, the Salve Regina, and the Litany of the Virgin) written in the variant of Middle Dutch spoken in fifteenth-century Bruges.65 In some works, the poet paraphrases in Middle Dutch and then doubles back, inserting the Latin of the original text into the vernacular verse. In others, he uses the device of the acrostic to structure and annotate the paraphrase.66 Whereas every paraphrase in the vernacular renders the prayers and liturgical texts most familiar to the layperson in the language of everyday life, De Roovere’s more artificed examples set up a tension between the realm of human experience and the timelessness of the Latin source material.

There is a relative abundance of information (by fifteenth-century standards) about how De Roovere’s work was received. His Ode to the Holy Sacrament, for instance, was approved by Bruges authorities as a means of promoting devotional solidarity among the populace. It was first posted as an illustrated manuscript in the parish church of St. Savior in 1456, and then was printed and more widely displayed in 1478.67 This may not have been an exceptional way for his works to be transmitted. According to Marcus van Vaernewijck’s account of the 1566 iconoclasm in Ghent, “beautiful poems and odes made by Anthonis de Roovere, the flower of the rhetoricians” were still displayed in the chapels of that city’s Carmelite convent in the middle of the sixteenth century.68

Although there is far less information about the original display or performance of the Marian works, there is reason to believe they were well known in the elite circles in which De Roovere moved. Their first recorded appearance is in a printed book, Rethoricale wercken van Anthonis de Roouere (1562), compiled by Eduard de Dene.69 In the preface, De Dene, who was also a Bruges rederijker, writes that he came across the poems in an old manuscript belonging to the author and the hantboeck of a Bruges Poorter (patrician) who had known De Roovere.70 De Roovere and this patrician may have gotten to know each other in the context of a group such as the Chamber of the Holy Spirit or another elite organization in the Bruges network, such as the Confraternity of the Dry Tree, whose members he worked with on several festive projects.71 The form of De Roovere’s Lof van Maria indicates that it was not produced for a large public performance. Instead, the complex structure of the poem, which contains an acrostic, requires its audience to see the text, rather than just hear it. Perhaps like the poems mentioned by Van Vaernewijck, it was displayed in a chapel.

Unlike many of De Roovere’s poems, the Lof van Maria does not initially appear to relate to a specific text of Marian devotion. Written in the first person, the poem is addressed to Mary. The first stanza, praising Mary for her role in the Incarnation, reads:

AVe opperste Eerwardichste Moedere

Alder Rechtuaerdichste Jubilatie

Als dijns Ghelijke Rechts gheen vroedere

Als Christus Jesus Abitacie

Puerste Leuen/Edelste Natie

Afgront Doorgaens Ontfaermen Meenende

Inghelicxste Natuere Vercoorne Spatie

Troostersse Elcken Compassie Verleenende

Met den ooghen van mijnder sielen weenende

kniel ick uwer moeder maechdelicheyt voren

daer tsvaders wijsheyt hem was vercleende

in v/ende in hier mensche gheboren

den Jugeerder/ende den verlosser vercoren

ende onsen godt/die onsen broeder nv

Aue Maria dies danck ick v.72

Hail highest and most reverend mother,

Most just jubilation.

No one surpasses your sense of justice.

As the abode of Jesus Christ

You are the purest form of life/the noblest nation,

An abyss, usually meaning compassion,

The most angelic chosen space in the natural world,

A comforter providing compassion for everybody.

Weeping through the eyes of my soul,

I kneel before your motherly virginity.

There fatherly wisdom humbled itself.

In thee and in this world was born as man

The Judge and the chosen savior

And our god who is now our brother.

Hail Mary, for this I thank you.73

The Lof is a refrein, the Middle Dutch version of the French ballade – a poetic form embraced by Burgundian court rhetoricians, consisting of several long stanzas ending in a repeating line (Hail Mary, for this I thank you). The refrein was a relatively new poetic genre when De Roovere wrote this poem, and like the ballade, it was written exclusively in the vernacular.74 This feature of the genre colors its reception. On the first level of reading, the language of the Lof conveys a sense of both the reassuringly familiar and the vividly distinct. Its interlocking rhyme scheme (aababbcbccdcddee) and the flow established by its cadence carry the poem smoothly forward, but as the English translation reveals, there are strange fissures in the devotional formula. “Most angelic chosen space in the natural world” or “abyss usually meaning compassion” are very off-beat verbal pictures. Rather than take up classic Marian topoi verbatim, these phrases attempt to create fresh images out of established ideas. The latter line, which is especially strange in English, draws on the associations of the Latin word for abyss, abyssus, which crops up repeatedly in the Vulgate; for instance, in the description of the limits of man’s understanding in the Book of Job (28:14) or in the rapturous appeal to God in Psalm 41, “Deep calleth on deep, at the noise of thy flood-gates. All thy heights and thy billows have passed over me.”75 In De Roovere’s poem, this familiar metaphor for the boundlessness of divinity is transformed by its translation into the Middle Dutch; afgront does not carry the intertextual reverberations of abyssus, giving the chasm in De Roovere’s poem an actual, physical identity that it does not possess as an oft-repeated word of scripture. Here, De Roovere performs an act of translation that extends beyond language to the mode of imagery; just as he translates the Latin into the vernacular, he makes the abstract particular.

In a way, De Roovere’s poetic prayers provide us with an illustration of the vernacular as Geert Grote envisioned it but driven toward a directly opposing end – one with relevance for how viewers might have understood Hugo’s painting. As Grote writes: “when a learned man hears something sacred expressed in his mother tongue, he seems to conceive in his mind something new or fresh by way of that mother tongue.” For Grote, the concrete nature of the vernacular could be instrumentalized but should ultimately be transcended. For De Roovere, the immediacy achieved by the vernacular is an end in itself. The poet’s idiosyncratic take on the doctrine of the Incarnation, rendered in the vernacular, yields a surprising, very concrete series of images that makes an article of abstract theology (the Immaculate Conception) uncomfortably particular; the “most angelic chosen space” refers in a concrete way to the place where the Incarnation happened, Mary’s womb. The most intense lines appear toward the end of the stanza: “Weeping through the eyes of my soul, I kneel before your motherly virginity. There fatherly wisdom humbled itself.” The kneeling poet who weeps with the eyes of his soul is an affecting figure that brings an intimate dimension to the alienated abstraction of Mary’s motherly virginity where fatherly wisdom humbled itself.

An Image within an Image and a Prayer within a Poem

My close reading of this poem aims to demonstrate that many of the strategies it uses are analogous to Hugo’s painting – not because the one is the direct source for the other, but because both employ contemporary understandings of how the vernacular might offer new ways of representing familiar narratives. The deployment of the vernacular in the poem is in some ways analogous to the “small time” of the Adoration; they both, as Acres writes, “work elliptically, as reticent cues to the sensorium of common life.”76 The Middle Dutch that the poet employs evokes the unmediated communication of daily life, the words to which his reader would have immediate recourse as he or she articulates his or her own thoughts. Likewise the depiction of suspended action and serial movement in the Adoration suggests the seamless passage of time, how one short moment follows the next in the human experience. Yet, in certain segments of the compositions, the evocation of the everyday can also draw attention to itself by breaking away from the customary forms for praising Mary or depicting the Nativity. The narrator’s ardent praise of Mary’s womb is as direct and clumsy as the passion of Hugo’s shepherds, who tumble into the stable. In the Adoration, the leftmost shepherd appears so excited that he almost falls over himself, with his hand to his heart, as if declaiming the weeping of the eyes of his soul. His knee is awkwardly twisted to face the picture plane, forming a small vignette of enthusiasm. With passages such as this and the strangely concrete afgront, the painter and poet mark their departure from the conventional formulae and capture the excitement of the Incarnation in a way that is, as Grote would say, new and fresh.

Despite the pervasive atmosphere of immediacy in both poem and painting, however, neither composition aims toward verisimilitude. As the prophets pulling back their trompe l’oeil curtains in the altarpiece forcefully remind us: this seemingly unrehearsed scene is indeed staged.77 The foreground of the image, the space of the prophets, is self-consciously separate from the middle ground, the scene of the Nativity, both in terms of their scale and the figures’ relationship to the viewer. Further, the size of the prophets cannot be reconciled with that of the Nativity figures within the space as represented. They are far too large, and they stand on a completely different ground plane. Instead, the half-length figures loiter on the edge of the picture, as our guides. One looks back toward the scene behind him, as we should, but the other stares out blank-faced, a disturbingly blunt depiction of the act of viewing that reminds us that the scene is presented and framed for our benefit.

The prophets provide a link between the world of the viewer and that of the Nativity, but more strikingly, they are an obstruction that pushes us out of our direct experience of the painting.It is clear that the men belong to a totally different historical moment than either the Nativity or Hugo’s viewers. The identity of these figures is still a matter of debate, but there is general consensus that one of them is Isaiah, prophesier of the virgin birth.78 In the narrative of sacred history, prophecy possesses a transhistorical scope that exceeds the human experience of time. The presence of Isaiah at the margins of the painting endows the passages of action in progress with exegetical scaffolding and puts the hectic celebration of the Messiah’s birth into perspective. The prophets are physical and conceptual markers of a larger structure that configures the shepherds’ in-the-moment passion.

The Lof van Maria also moves between the familiar and the distant, offering its reader a set of interpretive practices with which to navigate the otherwise disjunctive registers of history and experience. In the Lof, Anthonis de Roovere’s very direct verbal images are set into a larger structure with a gambit that is analogous to, if more cryptic than, Hugo’s curtains. The beginning letters of the poem point toward the rules of the game. In an initially puzzling fashion, the first two letters are capitalized, as is almost every word that follows for the next three quarters of the stanza. This is not arbitrary; extracted from their original context these capital letters comprise a second text embedded within the first:

AVe opperste Eerwardichste Moedere

Alder Rechtuaerdichste Jubilatie

Als dijns Ghelijke Rechts gheen vroedere

Als Christus Jesus Abitacie

Puerste Leuen/Edelste Natie

Afgront Doorgaens Ontfaermen Meenende

Inghelicxste Natuere Vercoorne Spatie

Troostersse Elcken Compassie Verleenende

Met den ooghen van mijnder sielen weenende

kniel ick uwer moeder maechdelicheyt voren

daer tsvaders wijsheyt hem was vercleende

in v/ende in hier mensche gheboren

den Jugeerder/ende den verlosser vercoren

ende onsen godt/die onsen broeder nv

Aue Maria dies danck ick v.

AV E M A R I A G R A T I A P L E N A D O M I N U S T E C U M

“Ave Maria, Gratia Plena, Dominus Tecum.” (Hail Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with you.) These are the first lines of the Ave Maria (or alternately, the Angelic Salutation). The prayer continues through the capital letters of the following stanzas. By including in his poem the words of the most popular Christian prayer, taken from Gabriel’s greeting to the Virgin at the Annunciation, De Roovere offers a context for the first-person relationship with the Virgin that is described in his ode to her. He reminds his readers that his individual devotion to Mary is embedded within the larger framework of Christian religious practice and sacred history. This protraction of context, from personal to collective and divine, does not mean that the sentiments of his poem lose their urgency, however. Instead, the figure of the poet who claims to weep “met den ooghen van mijnder sielen” acquires the weight and momentum of a much larger narrative than his own.

In De Roovere’s and Hugo’s compositions, the particular as grounded in sense experience does not merely provide a jumping off point for “our childish minds” (to quote Grote) on the way to somewhere more profound. Rather than the movement from immediacy to abstraction being a forward advance, it is a continuous oscillation between poles, between the greater historical meaning of Christ’s birth and the specific reactions of those who experience it. This movement, in the case of the poem, is relatively figurative – the initial appreciation of the sentiments of the text, followed by the recognition of the capital letters embedded in it, and a doubling back in order to read the two against each other. In the case of the painting, the movement is actual as well as figurative – tracking (with the mind, the eyes, and maybe even the head) the unfolding episodes across the expanse of the panel and perhaps stepping back to take in the image’s conceptual and physical framing. In both cases, the experience of reception is emphasized. Viewers and readers are made aware that what they are looking at or reading is not a mere representation of an event but an emotionally engaging commentary on it.

The Adoration in the World of Objects and Clients

The mode of reception fostered by both the Adoration and the Lof is a sophisticated and self-conscious one, and the existence of these compositions speaks to a select community of people capable of understanding them. Whereas both poem and painting may have been displayed in the relatively public space of a chapel endowed by an individual, guild, or confraternity, perhaps even a rhetorical chamber, potentially available to a whole range of viewers and readers, I suggest that both were clearly designed to appeal to an audience with a certain level of what Rothstein calls “visual skill,” a power of discernment that was based on knowledge of other sophisticated paintings and other acrostic poems.79 There is one important way in which the reception of the painting and poem diverged, however, and that is on the level of monetary value. It is important to emphasize that the person who commissioned the Adoration paid for the pleasure of the painting’s clever structure and its brightly colorful appearance. In the next section, I will argue the commissioners of Hugo’s paintings had a web of reasons for buying his work, reasons that included their religious function as altarpieces but extended beyond that to encompass worldly aims like the elevation of their social status and the aesthetic pleasure of problem solving.

It is this mode of reception, which requires an enjoyment of complexity on the part of its audience, together with the visual richness and actual monetary value of the painting that makes it implausible that the Adoration was commissioned by a practitioner of the New Devotion. As I have described, many aspects of the New Devotion, including its adherents’ use of the vernacular, did not diverge from conventional fifteenth-century Christianity. Indeed, it was not a set of specific beliefs as much as how they were put into practice that defined the New Devotion over and against lay existence, and the watchwords of the New Devotional way of life were poverty and simplicity.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life translated the ideals of poverty and simplicity into a way of life by carving out a place of retreat within the urban world. By renouncing material possessions and pursuing a life of humble introspection, the practitioners self-consciously drew a line between themselves and laypeople. For Grote, the concept of poverty stood in for spiritual purity, but it could only be an effective metaphor if penury was actually practiced, if destitution were pursued as a way of life. Like the Desert Fathers and the many ascetic monastic groups that followed them, the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life pursued a mode of being that was defined in opposition to the pragmatic negotiations of day-to-day urban life.Their ascetic identity was meaningful because it was exceptional.

In the same way, the emphasis placed by Grote on contemplation of the abstract and aniconic devotion can be understood as a mental equivalent to the renunciation of private property, a sacrifice in the name of spiritual purity that was remarkable because it was intentionally radical. The division here is between poverty and wealth, both spiritual and actual. And for this reason, we should not rush to attribute aniconism to the painting-buying public at large.

Patronage and Brass Tacks

The painting-buying public is the crucial variable in interpreting the Adoration of the Shepherds, because – simply put – a painting, especially one as big as the Adoration, exists in the world of objects as well as ideas. As Michael Baxandall observes in the opening lines of Painting and Experience, “a fifteenth-century painting is the deposit of a social relationship,” pointing to the economic exchange between painter and buyer as well as to the institutions and conventions that determine the production of a painting.80 We know that Hugo made several beautiful large-scale paintings for the elite of Bruges over the course of his career. In the case of the Adoration, we do not know the name of the patron (or patrons), but there are good, concrete reasons to believe that the painting was commissioned by the same type of client who had purchased altarpieces from Hugo in the past.

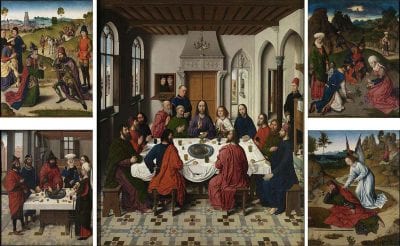

According to the estimate of Rainald Grosshans, it took between two and three years to complete a painting like the Adoration.81 This simple calculation reminds us that despite the relatively low estimation of panel painting in the hierarchy of late medieval luxury goods, a patron who commissioned a Netherlandish painting of the scale and quality of the Adoration would have been committing himself to an ambitious purchase.82 The contract for the Adoration does not survive, but we can deduce its approximate price based on an extant contract for an altarpiece by Hugo’s near-contemporary Dirk Bouts.

Bouts was commissioned to paint the The Holy Sacrament Altarpiece (fig. 7) by the Leuven Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament in 1464 and delivered it in 1467. The painting, which measures 185 by 294 cm (54,390 cm2), is more than twice as the size of the Adoration of the Shepherds (23,765 cm2), but it belongs to the same class of objects: large panel paintings by well-respected masters. The total payment for Bouts’s triptych was stipulated as 200 Rhenish guilders, or 8,000 d. gr. (Flemish groats).83 Figuring that Hugo would have been paid at roughly the same rate,84 the Adoration would have cost about 3,500 d. gr., or roughly 350 times the average daily wage for a stonemason in Bruges.85 According to the contract, Bouts was to receive around one quarter of his payment prior to the completion of the altarpiece, possibly in part to pay for materials.86 Even if Hugo accepted no remuneration for his labor, the pigment and panels that constituted the altarpiece would have required a considerable outlay.87

These speculations about the production of the Adoration are the closest thing we have to historical evidence about the commission of the altarpiece; the first recorded mention of the Adoration of the Shepherds places the painting in a Spanish collection in the early nineteenth century.88 The Bouts contract demonstrates that large paintings had an unavoidably economic character. Even if someone from the impecunious New Devotion movement commissioned the painting, Hugo’s panel still had to be paid for. And the presence of the image in the Rooklooster or another similar institution would not have negated the material nature of the painting, rather, the painting would have made the abbey church an uncommonly well-furnished space.89 No matter where it was displayed, the Adoration was a luxury good with a significant monetary value, an identity that runs counter to the poverty of body and spirit espoused by Grote and the New Devotion.90

In this section, I will investigate what sort of person the buyer of the Adoration was, rather than attempt to identify a particular candidate. Just as positing an analogy to De Roovere’s poetry was a helpful way to address the interpretative context of the painting in the absence of a definitive textual source, making an analogy to Hugo’s other clients serves as a method of approaching the material context in which the painting was purchased in the absence of a contract. In fact, there is a relatively consistent profile for the identified buyers of Hugo’s surviving panel paintings: they were all strivers of one kind or another, and his works had earthly tasks to fulfill in addition to spiritual ones. The three men who are known to have commissioned his work, Tommaso Portinari, Hippolyte de Berthoz, and Edward Bonkil, had different nationalities and worked in different professions, but they were all ambitious men with pronounced worldly interests that were manifested in their strategic relationships to princely power and their participation in Bruges’s network of elite institutions.91 In particular their involvement in confraternities demonstrates a type of religious conviction practiced through engagement with, rather than withdrawal from, the material world and provides a more likely milieu for the Adoration than the poverty of the New Devotion.

Tommaso Portinari, donor of the Portinari Altarpiece (fig. 8), is the best known and best documented of these men. Portinari was the head of the Medici Bank in Bruges, and at the time that he commissioned his altarpiece the mid-1470s, he had been living in the city for three and half decades. He integrated himself into the Bruges community by taking a leading role in elite organizations such as Our Lady of the Dry Tree, a closed confraternity that brought together wealthy foreigners and their prominent Flemish counterparts. (Anselm Adornes, Giovanni Arnolfini, and the painter Petrus Christus were also active in the leadership of the confraternity, and Duke Philip the Good was a nominal member).92 A long-time supporter of the Franciscan Observants, Portinari ingratiated himself with the reigning Burgundian duchess, donating a piece of land to her project to build an Observant monastery outside the city walls.93 Portinari founded a family chapel in Bruges’s St. James church, for which he secured burial rights for his wife and himself.94 Although the altarpiece ended up in Florence on the high altar of the church of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, there is evidence that he intended to display his large triptych by Hugo in St. James, where it would have served as a memorial for himself and his family as well as a very visible statement of his prominence in his adopted city.95

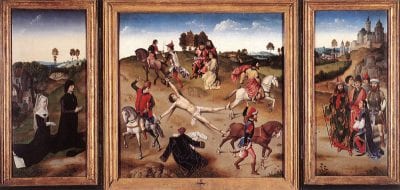

Hugo’s work made a similar kind of statement for the court functionary Hippolyte de Berthoz, whom he inherited as a client from Dirk Bouts. Berthoz commissioned theSaint Hippolyte Triptych (fig. 9) from Bouts, but the Leuven painter died in 1475 with only two of its panels finished; Hugo painted the left wing, featuring portraits of Berthoz and his wife. Berthoz was a high-ranking bureaucrat in the ducal chamber of accounts, which oversaw government finances.96 When the triptych was commissioned, he was serving as a clerk of the treasury at Charles the Bold’s court in Mechelen. Like many bureaucrats in the chamber of accounts, he hailed from Burgundy, but he married into a Bruges family and maintained a residence in the city.97Berthoz supported the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament, a group based in his parish church, St. Savior, the place where De Roovere’s Ode to Holy Sacrament was first posted.98 His triptych was installed in a chapel that he founded in the church, marking his status as an important parishioner of St. Savior and resident of the city.99

The biographies of these two patrons highlight not only the overlap between the people in Bruges’s literary and artistic communities but also the similar functions of literary and artistic compositions. As a signatory of the Confraternity of the Dry Tree, Portinari may have been involved with rederijkers, such as Anthonis de Roovere, in the planning of public events. Berthoz, on the other hand, was a benefactor of the literary arts; specifically, he was a patron of De Roovere’s French-language counterpart at the Burgundian court. In 1490, after assuming the very important position of maître de la Chambre aux deniers, he commissioned a poem from the Burgundian court chronicler and poet Jean Molinet, dedicated to his patron saint, Hippolytus, which also paid tribute to the Burgundians. Molinet embedded the motto of Berthoz and that of his wife in the poem as an acrostic in the shape of the cross of Saint Andrew. The words “vous seulement” and “dieu le scet” are situated in the text so as to form the Burgundian device and the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece.100 Here, a poem like Molinet’s could serve as a monument to social connections and spiritual belief just as well as a painting by Hugo.

Less is known about the Scotsman Edward Bonkil. He spent his adult life in Scotland, but recent research published by Lorne Campbell shows that he may have grown up in Bruges and certainly had strong Bruges connections. His father Robert Bonkil and his brother Alexander Bonkil were merchants who specialized in trade between Flanders and Scotland. Alexander was a citizen of both Edinburgh and Bruges, and Robert owned a house in Bruges, on the Bogaertstraat, where he may have raised his sons.101 Like Portinari and Berthoz, members of the Bonkil family attempted to integrate themselves into their adopted community via participation in the city’s network of institutions; Alexander and an Adam Bonkil (possibly his brother) belonged to the Confraternity of Our Lady of Snow, a large, inclusive organization which counted Duke Charles, artists, Bruges patricians, and wealthy merchants as well as the less privileged among its members.102

Like the altarpieces painted by Hugo for Berthoz and Portinari, the Holy Trinity Altarpiece staked a social and political claim as well as serving as testament of religious devotion. Bonkil was provost of the Collegiate Church of the Holy Trinity in Edinburgh and presumably donated the triptych to that church. Only the wings of the altarpiece survive (Edinburgh), representing Bonkil on the exterior and King James III, his son, and his queen, Margaret of Denmark, on the interior. Bonkil was the recipient of the patronage of James’s mother Mary of Guelders, who made him provost of her newly founded Trinity College church.103Edward, who is seemingly portrayed from life in his portrait by Hugo, probably ordered the altarpiece during a visit to Flanders.

Intersecting Social Circles, Overlapping Motivations: A Reassessment of Late-Medieval Patronage and Piety

Although it is unclear to what extent Bonkil considered the city of Bruges to be home, the patronage habits and affiliations of all three of these men and their families are typical of the social life of the elite in the urban Netherlands, with no fixed boundaries between members of the ducal court, Flemish patricians, foreign bankers, and well-to-do merchants.104 They asserted their presence in their adopted or native city through the foundation of chapels in parish churches (marked by works of art), and they also participated in organizations with explicitly religious aims such as the above-named confraternities as well as those without explicitly religious functions such as the tournament society of the White Bear or the rhetorical Chamber of the Holy Ghost.105 Members of a large confraternity like Our Lady of Snow may not have known each other personally, but they shared an allegiance and thus a commonality that could be exploited for other reasons.106 As a signatory of the smaller, restricted Confraternity of the Dry Tree, Tommaso Portinari was responsible for the organization and may have had closer contact with his fellow signatories Petrus Christus and Giovanni Arnolfini.107 Just as membership in the religious brotherhoods could have social advantages, involvement in organizations that were not explicitly religious always included an important religious element. The statutes of rhetorician groups like the Chamber of the Holy Ghost were modeled on religious confraternities, often celebrating a requiem mass for their deceased members in the manner of religious confraternities108 and even the participants in the joust of the White Bear retired to the Eeckhout Abbey for a vigil on the night before the event.109

Overall, there would have been no stark conceptual divisions between the political, religious, and aesthetic interests of Hugo’s patrons. If the donation of land to a monastery or the installation of a triptych contributed to the health of their careers and their social standing in addition to that of their souls, so much the better. It was not a coincidence that there was no house of the Common Life or Windesheim monastery within the walls of Bruges.110 In contrast to the renunciation of worldly goods advocated by the New Devotion, the key gesture for religious observance in places like the international commercial capital was gift-giving, a display and transfer of wealth that benefitted the giver as well as the recipient.111

In this context, art played an important role in mapping the political onto the spiritual; a triptych featuring family portraits by a prominent painter was a versatile instrument, shoring up its donors’ social prominence while honoring God, Mary, and/or the saints.112 The question, in this case, however, is how effectively a single panel without donor portraits like the Adoration of the Shepherds could participate in this economy of social prestige. There has been speculation that the Adoration and theDeath of the Virgin (also a single panel without donor portraits) were commissioned by ecclesiastical institutions rather than individuals, implying a certain disinterested remove from the ambition of profane life on the part of both the paintings and their patrons. It is evident from the large size of Hugo’s panels that they were destined for a public or a semipublic venue, such as the altar of a family or guild chapel, but the provenances of the paintings are murky, and it is difficult to pinpoint patronage solely on the basis of visual evidence.113 Briefly put, the absence of portraits does not point us toward a particular type of patron.

There do not seem to have been any hard and fast rules about how a painting commissioned for, or by, an ecclesiastical institution, a confraternity, or a lay individual was supposed to look in the fifteenth-century Netherlands. Some paintings like Rogier van der Weyden’s Crucifixion, donated by the painter to the Scheut Carthusian monastery, or his Miraflores Triptych, commissioned by King Juan II of Castile for the Miraflores Carthusian monastery, do not feature portraits. However, ecclesiastical or religious donors could be portrayed in the paintings they commissioned. For instance, Hans Memling’s Saint John Triptych painted for the St. John’s Hospital in Bruges represents the nuns and priests in the hospital management who donated the altarpiece. Dirk Bouts’s Holy Sacrament Altarpiece portrays members of the Leuven confraternity of the Holy Sacrament, but his Saint Erasmus Triptych commissioned by one member of the same confraternity does not.114

Hugo’s Adoration may have been commissioned by an individual who, like the patron of the Saint Erasmus Triptych, did not want to be portrayed. It could have been a gift to a monastic institution by a wealthy patron. Or, like Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross panel (Museo del Prado, Madrid), painted for the Crossbowman’s Guild in Leuven, Hugo’s Adoration may have also been commissioned by a group of laypeople, a guild, or a confraternity such as that of the Dry Tree or Our Lady of Snow.115 Rogier’s example is especially instructive in reference to the Adoration; although the image does not feature portraits or heraldic devices to point to its donors, it does incorporate the crossbow shape into the tracery of the image’s fictive frame and possibly even into the central compositional motif – the bodies of Christ and Mary, gracefully collapsed into mirroring bow-shapes.116 This crucial reference to the patrons is only legible with sufficient paratextual information, namely its position in the chapel of the Crossbowmen’s Guild in Our Lady Beyond the Walls in Leuven. Similarly, viewers of the Adoration would have been enlightened about that painting’s patronage through its original location. And although that information is unavailable to us now, judging from the size and aesthetic quality of the altarpiece, we can conclude that the Adoration would have reflected well, both religiously and socially, on the person or persons who paid for it.

Conclusion

As a status object, the Adoration would have represented the piety, wealth, and sophistication of the patron or patrons. At the same time, it certainly served a religious purpose as an altarpiece. I have argued that the overlap of personal status represented and religious function performed is characteristic of the elite, urban milieu for which the painting was probably made and that the visual complexity, large size, and vibrant coloring of the image run counter to the ethos of worldly and spiritual poverty espoused by the New Devotion movement. Its original audience must have been at once broader than the New Devotion, and yet narrower. The complexity of the work more closely connects to the kind of intricate vernacular poetry, exemplified by that of De Roovere, which was popular among social elites in the late fifteenth century. In Hugo’s painting, like De Roovere’s poetry, the process of taking apart layers of meaning requires a knowing, playful participation on the part of the audience – a presumably pleasurable engagement with these works’ riddlelike structures.117 This pleasure is not incidental to their meaning. Instead, it drives the process of reception. The effort to decode the compositions of Hugo and De Roovere may have provided a pretext for the sociable interaction of the confraternity members who were the painting’s likely original viewers, and the cleverness of the painting and poem would have gratified men like Tommaso Portinari and Hippolyte de Berthoz, whose artistic patronage was aimed at achieving the maximum effect in ducal, urban, and religious circles.

In a recent article, Jan Dumolyn argues that modern scholarship relies on anachronistic and misleading dichotomies to analyze early modern society: courtly vs. urban; civil vs. religious. He proposes, instead, that the lived values of a resident of Bruges would have been more of a bricolage of overlapping registers – consisting in large part of Christian morality but drawn also from judicial principles, feudal ideals, and economic practice.118 The multipurposed religious patronage of Hugo’s known clients and the religious function/social use of organizations such as the Holy Ghost and the Dry Tree confirm the easy comingling of the worldly and the spiritual, the particular and the abstract, in the daily life of a city like Bruges.

The assumptions that informed the foregoing analysis are first, that a painting is a product of the physical and economic circumstances of its making, and second, that viewers, then as now, bring a set of skills and a range of experiences to the viewing of a painting instead of a single programmatic idea of how paintings should work. And in fifteenth-century Bruges, the buyers of paintings had specific desires and needs for their purchases. Large paintings such as the Adoration of the Shepherds provided their owners with an opportunity to map the ambitions of the social and political spheres onto the spiritual domain. The formal strategy of the Adoration, like that of the Lof van Maria, works within this pattern of slipping registers, moving from the powerfully immediate and the everyday detail of an awkwardly twisted knee to the supra-historical level of the Incarnation. Rather than reading paintings through the ascetic ideal of aniconism, a paradoxical standard that they could have never reached by virtue of their very materiality, I suggest we look at how Early Netherlandish paintings actually functioned – and functioned very successfully – in the lives of the men who paid for them.