This paper focuses on Painter with Pipe and Book (ca. 1650) by Gerrit Dou, a painter much admired by an exclusive circle of elite collectors in his own time. By incorporating a false frame and picture curtain, Dou transformed this work from a familiar “niche picture” into a depiction of a painting composed in his signature format. Drawing on anthropologist Alfred Gell’s concepts of enchantment and art nexus, I analyze how such a picture would have mediated the interactions between artist, owner, and viewer, enabling each agent to project his identity and shape one another’s response. I thus treat the painting as the center of a complex web of social relations formed in the specific setting of early modern collecting.

At first glance, Gerrit Dou’s Painter with Pipe and Book (fig. 1), now in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, is a typical example of the many “niche pictures” the artist produced between the 1640s and 1670s. Featuring a solitary figure framed by an arched stone window and surrounded by appropriate accoutrements, it follows a formula that Dou used for a variety of subjects, including doctors, maidservants, scholars, and musicians. In Dou’s time, contemporaries like Philips Angel praised the artist’s extraordinary ability to conjure a “semblance without being” (schijn zonder sijn) in his paintings.1 In the niche pictures, such as The Doctor (fig. 2) and The Trumpeter (fig. 3), Dou accentuated his mimetic skill by employing techniques we now associate with trompe l’oeil easel paintings: the book and musical instruments protruding over the ledge, the illusionistic stone reliefs, and the foreshortened objects at the pictorial threshold. The Painter with Pipe augments these features with the strategic addition of a fictive frame and curtain, transforming it from a lifelike genre painting into a depiction of a painting.

This paper examines how such a work as the Painter with Pipe elicited specific responses from its intended viewers and, in so doing, shaped the relations between the artist, owner, and visiting spectators. A feigned painting can produce an unsettling—but also delightful—viewing experience for the beholder by raising questions about pictorial representation and sensory perception. Identified in the literature as a rare “true” trompe l’oeil in Dou’s oeuvre, the Painter with Pipe plays a sophisticated game with beholders, inviting them to consider how the illusionistic devices complement but also contradict each other.2 Jean Baudrillard, Pierre Charpentrat, and Louis Marin have theorized about the psychological effects of trompe l’oeil imagery,3 while Celeste Brusati has demonstrated that the makers of such “pleasant and praiseworthy” deceptions earned the admiration of a sophisticated clientele among Europe’s elite in the early modern period.4 This paper builds on this recent scholarship by identifying and examining the stakes of Dou’s complex visual game. I propose that the anthropologist Alfred Gell’s concept of enchantment provides a useful framework for this investigation.5

Through the analysis of Dou’s painting, this paper also seeks to explore the utility of Gell’s theory to the study of high-value paintings destined for collectors’ cabinets in the seventeenth century. It may seem surprising to apply the ideas of Gell, who has argued for “an attitude of resolute indifference” towards aesthetics, to such examples of supreme craftsmanship as trompe l’oeil easel paintings. It is clear, however, from his essay “The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology,” that in calling for “methodological philistinism” Gell is far from urging anthropologists to ignore the formal qualities of art objects. On the contrary, he repeatedly states that the visual and material characteristics of the object are crucial to the way it acts upon the beholder. Indeed, enchantment happens when the viewer is startled by the technical expertise demonstrated in an art object. Yet the element of surprise can be triggered only if the viewer possesses knowledge of the technology of production and standards of evaluation. Gell’s scrutiny of the art object’s power thus takes into account the sense of wonderment associated with the viewing of trompe l’oeil described by Baudrillard but at the same time grounds the discussion in historically specific conditions of production and reception.

In addition to demanding greater attention to cultural and social contexts in which trompe l’oeil was viewed, Gell’s concept of enchantment offers a different explanation of the powerful impact of the image on the beholder. For Gell, the viewer’s sense of awe arises not just from observations of the visual properties of the work of art but from his or her recognition of the powers possessed by the people who made or control that object. Moreover, enchantment often unfolds in a web of social connections, with the work of art mediating the relations among the artist, the collector, and visiting spectators. Art historians have sourced Gell’s insights effectively to study the role of objects in ritual activities; for example, a cultic object possessing miraculous powers encourages devotees to venerate it, or an official portrait acts as a physical manifestation of a ruler in all parts of his empire.6 While Dou’s Painter with Pipe was not an object connected to formal rites, its viewing would have been choreographed in ways not unlike the organizing of a ritual. At issue is not only who had access to such an exquisitely crafted work but the lived conditions in which reception took place.

The Painter with Pipe serves as a thought-provoking case study, for it was not just a trompe l’oeil painting by a famous artist but also a “depiction” of a picture in his signature compositional format. What did it mean for Dou to declare his distinctive creation to be a mere image on a flat surface? As a work by an artist who was known for his skill at naturalistic rendering, how did this counterfeit niche picture enchant the informed viewer? How did such a piece help the owner impress his visitors, and how might the latter use the occasion to affirm their own cultural capital? This paper draws on Gell’s concepts of art and agency to address these questions. In the process, I seek to demonstrate that Gell’s anthropological theory can yield insights into the social role of paintings in the elite circles of early modern European collectors.

Gerrit Dou, “excellent painter of life in miniature”

Before his critical fortune started to fade in the late eighteenth century, Dou’s refined, painstakingly detailed genre paintings made him one of the most admired Dutch painters in his homeland and beyond. In 1641, he was included in Jan Jansz. Orlers’s Description of the City of Leiden as one of the “illustrious, learned and renowned men” of his hometown.7 Orlers calls the then twenty-eight-year-old Dou an “excellent master, especially as regards small, subtle and curious things,” and observes that his paintings were “highly valued by art lovers and dearly sold.” The painter-author Angel extolled Dou as an exemplary artist in the Lof der Schilder-konst (Praise of Painting), a lecture delivered in 1641 to Leiden artists and art-lovers.8 Recurring words and phrases such as “neat” (net), “curious” (curieus), and “true to life” (gelyk als eygen) in contemporary sources indicate that collectors esteemed Dou’s works for their polished finish and lifelike simulations of figures and objects.9 Yet the descriptions suggest something more than an appreciation of technical skill; indeed they convey a sense of wonder at the microscopic details—“refined minuteness” in Simon van Leeuwen’s words—that filled the small panels.10

The so-called niche picture, which Dou developed in the 1640s and would go on to use repeatedly for almost three decades, accentuates the artist’s ability to create images of convincing illusionism. The Doctor (1653), a characteristic example, is conceived as a view through an opening, with the simulated window closely following the physical contour of the painting. This correspondence between the depicted and actual boundaries encourages a conflation of the fictive masonry wall and the picture plane. Objects and figures that seem to project beyond the pictured wall thus also threaten to transgress the pictorial threshold. These include a luxuriously soft carpet draped over the windowsill, partially covering the grisaille stone relief; a copper basin positioned so that its wide rim extends beyond the window; and a large book on the right, a corner of which overlaps the edge of the wall.

Although the suggested breaching of the picture plane is a typical feature of trompe l’oeil images, the depicted objects in Dou’s niche pictures are too small to be literally confused with reality. There may have been a practical explanation for the diminutive sizes of Dou’s panels: his meticulous rendering of minute details made it almost impossible for him to work on a large scale. Yet, the very manner of painting produced such persuasive simulations of visual phenomena that the artist was designated an “excellent painter of life in miniature.” This combination of convincing surface descriptions and the tiny size of the painting creates a paradox between verisimilitude and artifice.

Scale is not the only indicator of the artificial nature of Dou’s paintings. The arched masonry window, the distinctive compositional device shared by Dou’s niche pictures, was not a common feature in Dutch domestic architecture in the seventeenth century. While there have been suggestions that the window’s function was to monumentalize the genre pictures,11 I agree with Eric Jan Sluijter that the repeated use of such a prominent but unusual motif extracts the framed scene from quotidian life.12 I would further argue that the framing device offers opportunities for Dou to manipulate the rules of perspective to create abrupt shifts in space.13 For example, The Trumpeter from the 1660s (fig. 3) consists of two distinct spatial zones. The central figure stands on the left side of a shallow foreground area, while a tapestry is pulled to the right to reveal a group of revelers in the interior. The difference in scale between the figures in these two zones is pronounced, but there are no transitional elements in the composition to create a gradual recession into the distance. Instead, the background scene is contained by the drapery on the right, the trumpet at the top, and the body of the trumpeter on the left. Different light sources—the foreground is lit by a strong raking light from the upper left, whereas the merry company is illuminated by light entering through a window deeper in pictorial space—heightens the sense of separation. The compositional idiosyncrasies combine to give the background the appearance of an image within an image.

Dou’s skill at rendering an array of materials is on full display in The Trumpeter. He uses short parallel strokes to simulate the weave of the carpet that drapes over the sill but produces stronger highlights on angular folds to suggest the reflective leather of the curtain on the right. Likewise, the artist’s depiction of the dish and the ewer constitutes a pictorial parallel to Angel’s assertion that painting should be capable of imitating various kinds of metal.14 The silver body of the ewer has softer highlights, which differ from the brighter reflections off the gilded decorations. Such finely wrought textural renderings are, however, juxtaposed with blatant spatial disjunction. The viewer is thus challenged to process the contrast between persuasive textural simulations and reminders of the illusory nature of mimetic artistry.

The central figural scene in the Painter with Pipe (fig. 1) looks similar enough to that in The Doctor and The Trumpeter. It shows a male figure at an arched window holding a pipe in his left hand and resting his right on an open book that sits on the windowsill. He looks up from the book and engages the viewer’s gaze, as if he has been distracted from his reading. Two more figures, one standing and the other seated, are barely visible next to an easel in the dark background. Dou again suggests the transgression of the pictorial threshold: the painter is pushed into the shallow space behind the window, with his left forearm and foreshortened pipe extending beyond the opening; the book, with its stiff parchment pages carefully differentiated, hangs over the ledge and casts a shadow over the wall surface beneath, to which a creased and curling cartellino is affixed. The effectiveness of these pictorial maneuvers depends, of course, on Dou’s celebrated ability to render the objects in a lifelike fashion.15

The Doctor and The Trumpeter provide clues—miniature size, improbable setting, spatial compression—that ground the paintings as crafted images on flat supports. Dou problematizes this distinction between representation and referent in Painter with Pipe by adding a few well-established trompe l’oeil devices to a niche picture. Surrounding the figural and architectural features is a depicted black frame with an illusionistic brass rod attached at the top. Hanging from this rod is a fictive green curtain, which has been drawn to the right to “reveal” the image of the smoking painter at a window. Curtains and draperies are standard features in Dou’s niche pictures, and he has in fact included brown swags of fabric behind the stone window. However, the green curtain is understood as an object not within the framed scene, but hanging “in front of” the panel. The false frame and curtain purport to belong to the “expositional accessories” of the painting,16 and their inclusion establishes two orders of simulated space. They negate the already complex spatial organization of the niche picture, emphatically declaring the central scene to be a mere illusion on a flat panel. Of course the viewer also recognizes that the curtain and frame are themselves no more than simulations. The artist thus establishes a tension between recession and protrusion, generating a push and pull effect between depth and surface. By alternately producing, then counteracting illusionistic effects, the Painter with Pipe puts the spotlight firmly on Dou’s artistic accomplishment. It claims to expose the artifice of the niche picture yet ultimately withholds the secret to how the artist achieved such dazzling effects.

“Anti-Painting” and the Failure of Perception

Dou’s Painter with Pipe, as a counterfeit painting, participates in the development of a specific kind of deceptive easel painting in the second half of the seventeenth century. Depicting feigned letter racks, cabinet doors, or framed pictures, these paintings are now considered examples of trompe l’oeil, even though the term did not come into use until around 1800. Academic theorists in the eighteenth century and later opined that, in attempting to deceive the viewers with heightened verisimilitude, the trompe l’oeil failed to express ideals and truths, which ought to be the highest goal of art.17 More recently, scholars such as Baudrillard, Marin, and Charpentrart have argued that trompe l’oeil paintings raise profound questions about perception and representation. Baudrillard highlights the radical nature of such pictorial creations by referring to them as “anti-painting.” What Baudrillard implicitly defines as “painting” seems to correspond to the istoria described by Leon Battista Alberti in his De Pictura.18 Against the narrative scenes staged in perspectival spaces, trompe l’oeil images—according to Baudrillard—offer painted surrogates of things in the “unreal reversion to the whole representative space elaborated by the Renaissance.”19 In other words, the quality of trompe l’oeil paintings that disturbed academic authors, i.e.,the collapse of the distinction between image and referent, is what intrigues modern commentators.

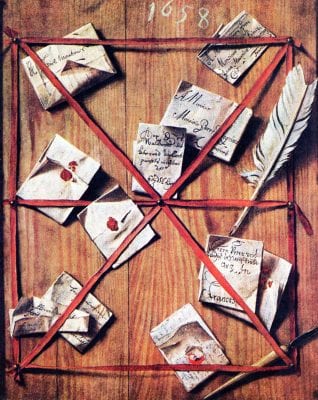

Consider, for example, Wallerant Vaillant’s Wooden Board with Letters and Writing Implements (fig. 4). The picture portrays an inherently flat object, namely, a letter board. Because the board is parallel to the picture plane, with its boundaries coinciding with the edges of the support, an identification between the board and the picture surface is implied. It thus presents the viewer with an opaque surface rather than a recessive view into a three-dimensional realm. In order to produce vivid simulations of the letters and writing instruments, Vaillant carefully modeled the forms and captured the quality of the reflections off different materials. The artist imagined a raking light from the upper left, which allowed him to heighten the sense of shallow relief by supplying the life-size motifs with dark cast shadows. Using only paint, Vaillant has transformed the paper support into two wooden planks, on which letters and writing implements are held in place by leather strips. The depicted objects appear to project into a zone of virtual space in front of the picture plane, rather than occupying perspectival space behind it.

Paintings such as Vaillant’s Wooden Board (fig. 4) thus challenge the understanding of a painting as a representation of figures and objects in three-dimensional space seen through a transparent screen. They conjure the presence of objects rather than offering images explicitly as representations of those objects. To Baudrillard and Charpentrart, such effects are unsettling. In psychoanalytic terms, linear perspective is an instrument of pleasure and power in that it purports to be constructed around the viewer’s vantage point, allowing him or her a mastering gaze over the representation. The trompe l’oeil, by inverting that scheme, threatens this relationship between viewer and picture. Invoking Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s argument that depth is invisible, Marin and Hanneke Grootenboer also remark that Albertian perspective, a geometric model for representing the third dimension in painting, leaves behind a blind spot. Marin explains that a viewing subject cannot actually see depth, for it is “the very axis of [his/her] vision.” To consider depth as “breadth in profile,” the subject would have to leave his/her original position, that is, the fixed point of view dictated by a perspectival composition. Trompe l’oeil, like anamorphosis and other distorted projections, exposes this blind spot and draws attention to the incompleteness of visual perception.20

These recent studies, which are informed by psychoanalysis and phenomenology, probe the impact of reversals of perspective on an individual viewer, but they appear to posit a universal response across periods to the visual effects.21 The question is whether that is a valid assumption. We do find similarly bemused responses in early modern sources. Samuel Pepys, the English diarist, recorded in his entry for March 15, 1668, that two friends brought to his home “several things painted upon a deal Board.” He claims to have been confused before discovering that the objects and the board were painted simulations. Pepys then praises the craftsmanship of the work: “even after I knew it was not board, but only the picture of a board, I could not remove my fancy.”22 In the eighteenth century, Denis Diderot would recall Oudry’s painted depiction in a similar way: “Our hand felt a flat surface and our eyes . . . perceived a relief: so that one could have asked the philosopher which of the two senses, whose indications contradicted each other, was the liar.”23 These commentaries register a sense of tangible, persisting doubt, with the viewer wavering between accepting the illusion of three-dimensionality and acknowledging the deception. While Baudrillard and others highlight the psychological effects trompe l’oeil images produce in viewers, the language in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sources suggests that the trompe l’oeil images were more sources of delight than “disturbing hallucinations.”

To shed light on how the trompe l’oeil participated in the contemporary discourse on representation in early modern Europe, the theoretical analysis of the images needs to be combined with a consideration of the prestige enjoyed by deceptive artistry in that culture.24 To that end, the studies of Brusati, Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, and Victor Stoichita, for example, focus on the appeal of mimetic artistry to an elite circle of art lovers. These scholars have also established that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, trompe l’oeil images would have been viewed in collectors’ cabinets.25 Moreover, the viewing process was not a private affair; instead the paintings were received in a social setting. How did trompe l’oeil paintings, by inspiring probing questions about perception, shape the power relations among different viewers in the environment of an elite collection? I propose that Gell’s concept of “enchantment” offers a productive model for considering this question.

The Enchanting Trompe l’Oeil

Gell uses the term “enchantment” to refer to an interaction in which a work of art impresses—or even intimidates—the viewer with its technical excellence.26 Gell’s designation of art as “a means of thought-control” may seem to agree with the disorientation described by modern theorists of trompe l’oeil, but he provides a different explanation of the source of that bewilderment. Following Gell’s concept, the power of a trompe l’oeil painting derives not only from its negation of the viewer’s confidence in his or her perception. Instead, its efficacy lies in the artist’s magical skills (and, by extension, the power of the owner who secured the artist’s services), which the viewer infers from his or her study of the object. Furthermore, even though he argues that human beings seem to be universally predisposed to be attracted to technical virtuosity, the artist’s manipulation of a medium to produce enchanting effects and the viewer’s propensity to be persuaded rest on both parties’ knowledge of that medium. Gell therefore also insists that artists and viewers are situated in particular societies, where the technology of enchantment is configured and produced in specific forms.27

Underpinning the concept of enchantment is Gell’s definition of art as “the outcome of technical process,” which sees the expertise embodied by the art object as central to its social function. In Gell’s analysis, virtuosity is the crucial quality that creates the mismatch between the artist’s perceived powers and the viewer’s own and is thus the key to an art object’s capacity to impress or seduce. Notice again how Pepys described his experience of viewing the painting brought to him by his friends by writing that even after he had ascertained that he was looking at a picture of a board, he could not “remove his fancy.” The sense of astonishment recorded in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century accounts suggests that the beholders of trompe l’oeil easel paintings recognized technical mastery that surpassed their expectations or even comprehension.

But what did Dou’s and Vaillant’s viewers understand as the “technical process” of oil painting? Dutch treatises and verbal testimonies in the seventeenth century offer some insights into their expectations. Angel, writing in mid-century, urges painters to capture the eye of the viewer with convincing renderings of optical effects.28 He argues that a most praiseworthy painting is one that is so close to nature that it does not reveal the manner of the artist who made it.29 Van Hoogstraten, a pioneer in developing the feigned letter rack, likens a perfect painting to “a mirror of nature which makes things which do not actually exist appear to exist, and thus deceives in a permissible, pleasurable, and praiseworthy manner.”30 Lifelikeness and deception are thus central to the Dutch discourse on painting in the seventeenth century.

Yet enchantment goes beyond the appreciation of well-crafted images; it presupposes a familiarity with painting techniques on the viewer’s part. The viewer holds knowledge and expectations with regards to the medium of oil painting, but he or she is unable to understand fully how makers of trompe l’oeil images could create such radical deceptiveness. Commentaries about Dou suggest a similar difficulty in imagining the genesis of his paintings. His pictures, which were called works of wonder and curiosity in his own time, inspired fanciful descriptions of his method. Joachim von Sandrart recounts that Dou “painted all his works wearing glasses, even when he was still young” and spent days on the most minute details in his paintings. He also claims that Dou waited for the dust to settle when he sat down to paint and was fastidious in protecting his pigments and brushes.31 In his biography of the artist, Arnold Houbraken speculates that Dou created his finely detailed pictures by painting “with the greatest care looking through a frame strung with [horizontal and vertical] strings.”32 The French author Roger de Piles meanwhile claims that Dou painted with the help of a convex mirror.33 Such speculations reflect the authors’ struggles to articulate their experience of viewing Dou’s work in the terms of conventional artistic discourse. By suggesting that Dou went to extraordinary measures to create his paintings, these authors imply that the artist’s achievement exceeded what was thought possible for the medium. In turn, the viewers’ ultimate failure to retrace and discover the procedure by which a painting like Painter with Pipe was generated made them keenly aware of the artist’s mastery of his craft.

Authors of the early modern period often discuss trompe l’oeil in terms of a contest between artist and viewer, echoing Gell’s characterization of enchantment as a tool in “psychological warfare.” Karel van Mander, for example, writes that Jan Gossaert impressed Emperor Charles V with a counterfeit silk tabard made out of white paper. Instead of being punished for his deceit, Gossaert won the admiration of his patron, the Marquis of Veere, and the emperor himself with his ingenuity.34 Houbraken tells a similar story about his teacher Van Hoogstraten. According to Houbraken, Emperor Ferdinand III admitted that Van Hoogstraten had deceived him with a vivid still life, for which the emperor honored him with a gold chain and medallion.35 By the seventeenth century, then, the social status of the deceived viewer was seen as the measure of the artist’s success. Whether the events were true or merely described in accordance with established literary tropes, the authors make a statement about the power of art by describing a reversal of the hierarchical relationship between the artist and the eminent patron. Dou, by making the central figure in this painting a painter who engages the viewer’s gaze, further emphasizes the power of artistry in a witty confrontation.

The Nexus of Agency

In the seventeenth century, a beholder might have been impressed by the virtuosity displayed in a painting, but the agency of the work extended beyond this enchanting effect in individual viewings. Gell’s “art nexus,” which maps the relations among the artist, viewers, and the owner of an art object, asks how cultural and social forces provided the impetus to create an art object, and how that object could then inspire certain behaviors in the viewers. It represents a productive approach for elucidating how a prestigious trompe l’oeil painting operated as a center of social networks forged in its historical environment.

Even though the provenance of Painter with Pipe can only be traced back to the eighteenth century, certain inferences can be made about its intended viewers—the “recipients” in Gell’s art nexus. Biographies of Dou marvel at the exorbitant prices of his paintings, some of which sold for sums equivalent to a master craftsman’s yearly income.36 Available sale records support their assertions, as works attributed to Dou are frequently among the most expensive listed in the inventories of substantial collections of the period.37 The prices he commanded would have limited his potential buyers to a small circle of wealthy collectors or prominent dealers, among whom he had an established reputation.38 As Brusati and Wheelock have demonstrated, trompe l’oeil paintings likewise circulated among similar groups, who appreciated the ironic critiques of representation and visual perception.

These knowledgeable consumers from the upper echelons of European society formed a group of individuals referred to as liefhebbers (translated loosely as “art-lovers”) by Netherlandish writers in the seventeenth century. In the Netherlands, some nonpractitioners registered as liefhebbers with the guild of St. Luke, seeking formal recognition of their roles as supporters of the visual arts.39 Van Mander uses the term in his Schilder-Boeck to refer to individuals who not only had the financial resources to amass substantial collections but also had an interest in promoting living artists.40 Analogous terms appear in seventeenth-century Italian and French writings—virtuosi and curieux respectively—where they are applied to individuals ranging from rulers and aristocrats to prominent burghers in the urban centers of Europe.41 The term liefhebber, then, was less a designation of social class than of cultural standing, for individuals could, through the practices of collecting and connoisseurship, claim membership in this elite circle.42

Art collecting provided the site for individuals to demonstrate their discerning eye and familiarity with current art criticism, allowing them to negotiate their cultural status. Travelers’ accounts and art treatises from the period indicate that collectors received visiting liefhebbers to their residences, creating an environment of communal viewing and discussion.43 In this setting, collectors strove to impress with paintings by canonical masters in their possession, while viewers were expected to demonstrate their visual acuity, familiarity with the personal manners of canonical artists, and an ability to deploy the language of criticism.44 Individuals made their taste visible in their purchases and their opinions in discussing art, as their agreement with accepted standards of excellence would confirm their taste. The term “taste” here refers to a set of shared preferences that enable a community to construct its group identity.45 In relation to the appreciation of trompe l’oeil paintings, those preferences were shaped by several factors that conditioned the viewer to react in a particular way. These include the predictable motifs, viewing conditions, and existing accounts of similar displays of consummate skill.

The settings in which fine examples of trompe l’oeil were viewed were thus far from neutral. Beholders encountered these paintings under specific conditions in collectors’ cabinets, where the dazzling visual effects conferred prestige not only on the artists but also on the owners and guests. For example, Pepys had to be granted access to the king’s cabinet to see the trompe l’oeil pictures in the royal collection, and, in a more informal manner, his friends revealed to him an illusionistic letter board on a visit to his residence.46 Enchantment took place within a specific social milieu, which shaped the interactions among the painting and various participants in the practice of art collecting. The paintings therefore not only captivated individual viewers but were also sites for painters and viewers to construct and project cultural and social identities.

For all their eye-fooling tricks, the works by Dou and Vaillant share familiar tropes with other trompe l’oeil easel paintings of the period. The artists draw on a restricted range of motifs—letters and pens attached to letter racks, personal items hanging from cabinet doors, curtains drawn aside to reveal depicted paintings—to generate the momentary illusion of objects projecting forward from a flat surface. At the same time, the presence of stock elements signals to the viewer that he or she is looking at a painting. No matter how lifelike their images, early modern European artists reference artistic precedents and conventions in creating their compositions. The Painter with Pipe draws not so much on actual smoking men, stone windows, or other objects represented, but on Dou’s niche pictures and the Netherlandish tradition of descriptive artistry. Dou’s prototype, to use Gell’s term, consists of the artistic solutions achieved by artists (including himself) engaged in similar pictorial experiments.

The verbal accounts of reactions to trompe l’oeil easel paintings, while vivid in the description of the viewers’ amazement and admiration, likewise follow a recognizable pattern: the authors claim to be temporarily confused by the painting before discovering that it is a clever deception; they may feel compelled to touch the surface of the picture to verify its flatness. The formulaic character of the compliments suggests that the writers were conforming to literary conventions and invoking famous topoi, which reminded the reader not to take the textual accounts at face value.47 At the same time, these descriptions both register the historical viewer’s appreciation of illusionistic artistry and play a part in shaping it. The ability of a trompe l’oeil painting to inspire wonder in its viewers is contingent upon visitors’ shared knowledge of artistic tradition, as well as the language and standards for evaluating descriptive artistry. This is not to suggest that the contemporary proclamations of the power of trompe l’oeil paintings were deliberately misleading, but that knowledgeable viewers came to these works in the seventeenth century with pre-existing expectations and conceptual tools.48

Collectors and artists alike ensured that viewers responded in the desired manner by carefully managing the encounters with these paintings. Anecdotes from the period indicate that trompe l’oeil images were often installed among the furnishings of a residence. The owner of the collection could then stage the visit to create fleeting confusion, recognition, and delight for the visitor.49 A record of a well-known example comes from Pepys, who saw Van Hoogstraten’s Perspective from a Threshold at the home of Thomas Povey. Van Hoogstraten’s life-size canvas, which offers a carefully constructed view into a deep interior, was installed behind a door. Povey was the one who could “activate” the illusion by opening the door to reveal the fictive view to his guests.50

Artists could also present their works in such a way as to control the circumstances of viewing more precisely and to draw attention to specific fictive devices. Dou was known to both place his small panels in cases and to attach painted doors to the frames.51 These devices invited the beholder to interact physically with the painted ensemble, while also situating him or her at the optimal viewing distance from the picture.52 The sense of revelation created in the act of opening the cases alludes to veiled or shuttered devotional images, enhancing the prestige and value of Dou’s artistry. The simulated black enclosure and curtain in Dou’s Painter with Pipe, I argue, thematize the drama created by the artist’s own strategies of presentation.

The references to pictorial precedents, the development of literary conventions in art criticism, and the staged display of trompe l’oeil paintings—all these factors ensured that the viewing experience was highly structured in the seventeenth century. It is in this context that some recent art historical studies have referred to the trompe l’oeil as a “ritualized form.”53 The reception of early modern trompe l’oeil paintings is analogous to certain aspects of what historians have called “ritual-like activities.”54 The adherence to a restricted set of motifs and the choreographed process of viewing mark the formalism of the genre, while the current discourses and pictorial conventions—components of what Gell calls the prototype—provided a framework for the reception of painted deceptions.55 The appreciation of these witty pieces was not a private or spontaneous process, but was instead shaped by the recipient’s prior knowledge of the prototype and the staged viewing experience.

In the production and reception of Dou’s Painter with Pipe, the artist, various beholders, the painting, and artistic precedents relate to one another variously as agents and patients.56 While Dou captivated the spectator through the visual qualities of the painting, the owner impressed other viewers with his or her discernment and wealth in securing a work by the celebrated master and properly staging its reception. The preferences and standards articulated in this environment would in turn form part of the evolving artistic tradition. In that sense the recipients were not simply passive enchanted spectators but instead played a significant role as agents in the generation of future works of art. Paintings such as Dou’s Painter with Pipe became examples of artistic repertoire from which subsequent artists could draw. Or, to borrow Gell’s terminology again, the indexes became part of the prototype. Gell’s art nexus highlights the fact that production and reception happen over time and in social spaces, so that the relations among artist, painting, and viewers are fluid and reciprocal.

Enchantment and Distinction

It is notable that Dou’s Painter with Pipe was more than an expertly crafted trompel’oeil piece; it was a variation of his trademark composition—the niche picture.57 Dou’s niche pictures were full of convincingly rendered details, but their small scale, unrealistic setting, and spatial manipulation declare them representations set behind a transparent picture plane. The Painter with Pipe, as a feigned niche picture, confronts the viewer with the opacity of a simulated presence. Yet it is through the lifelikeness of the counterfeit curtain and frame that such a presentation was made possible. In this case, the highlighting of the artist’s superlative artistry is effective only if the visible traces of his hand are downplayed. The technical means of achieving such beguiling effects thus remain hidden, preserving the enchanting spell over the beholder.

Dou’s Painter with Pipe, as a trompe l’oeil niche picture, is thus doubly reflexive. It also makes an additional demand on viewers, who have to draw on their knowledge of the artist’s oeuvre and the tradition of illusionistic artistry to appreciate the playful imagery. As Brusati has demonstrated, enterprising artists in the seventeenth century often employed meaningful motifs and learned allusions to appeal to their sophisticated viewers. Far from meaningless scraps, the objects featured in letter rack paintings often performed this function. Van Hoogstraten, for example, includes the medallion and gold chain conferred by Emperor Ferdinand among the carefully arranged gentleman’s accoutrements in his trompe l’oeil still lifes. Vaillant’s letter rack features inscribed sheets and envelopes that hint at his relationships with prominent collectors.58 In Painter with Pipe, Dou refers to himself in a slightly different manner. Instead of honors bestowed by aristocratic patrons or networks forged with connoisseurs, Dou’s identity is defined here through a distinctive format—the niche picture—and the technique for which he won renown.

If the niche picture format is associated specifically with Dou, the curtain signifies the power of eye-fooling images more broadly. Despite Gell’s apparent skepticism of the idea that art communicates meaning through a visual code or symbols, the semiotic approach to studying visual material is not necessarily at odds with his project of analyzing agency.59 Some trompe l’oeil devices not only produce effects of illusion but can ultimately be traced to classical tropes of artistic excellence. The painted fly that appears to have landed on the surface of a painting, for instance, alludes to a passage in Philostratus’s Imagines and Filarete’s anecdote about Giotto deceiving Cimabue with a painted fly.60 The combination of a simulated frame and feigned curtain is another familiar device. An examination of the illusionistic curtain, a multivalent motif, demonstrates that technical execution and iconographic communication are intimately linked in how a painting acts upon the viewer.

As has been frequently observed in the art historical literature, to an informed viewer in the seventeenth century, the curtain would have brought to mind the legendary contest between the ancient Greek painters Zeuxis and Parrhasios, a story that had become a topos for discussing illusionistic artistry by this time.61 Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers likened contemporary artists to those ancient masters, and the painters themselves inserted references into their pictures to encourage the comparison. The classical association carried by the curtain communicates the very idea of artistic virtuosity, and thus complements the trompe l’oeil effect created by the motif. The curtain would have been a particularly apt device for Dou, who was called the “Dutch Parrhasios” by the Leiden poet Dirk Traudenius.62 At the same time, by showing their understanding of the evocation of the classical story, as well as its purchase in contemporary criticism, viewers could confirm their knowledge and sophistication as liefhebbers.

The curtain further confers a sense of prestige and value on a painting by creating what Wolfgang Kemp calls a “veiling effect.” The veiling of images has been a common practice in Christian worship since the Middle Ages. Miracle-working images are kept from view to heighten their efficacy when they are displayed in times of need.63 The use of drapery was adopted in art collections in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the practice was documented in Italy, France, and the Netherlands. It has been traditionally assumed that collectors sought to protect their pieces from light, but, as Kemp points out, such concerns for the conservation of oil paintings arose at a later time.64 Instead, Kemp argues that the curtain might be seen primarily as a device that accentuated the aesthetic value of the picture it veiled. In an early modern collection, where paintings were hung in a dense, wallpaper-like pattern, picture curtains allowed the collector to control the display of select paintings.65 Nicolas Poussin, for example, explained that veiling the pictures would bring attention to the works one by one, so that the viewer did not become overwhelmed by too much visual material all at once.66

Just as the acts of concealment and revelation deepened the divine mystery in a religious setting, covering cabinet pictures with curtains generated a sense of anticipation and enhanced the paintings’ impact. Conversely, coverings could also be a means of controlling images that were thought to arouse problematic responses from viewers. Sources suggest that erotic images, for example, were intended to be shown in private settings to privileged beholders.67 The curtain thus not only conferred honor to a painting, but it could also connote affective power, whether its source was religious or erotic. The motif of the counterfeit curtain, by alluding to the actual picture curtain, appropriates this veiling effect. By inserting the false frame and curtain in the Painter with Pipe, Dou aligned his painting with images that possess spiritual or affective powers, allowing him to claim potency for his own work. As signifiers of visual deception, those stock trompe l’oeil motifs further intensify the painting’s enchanting effects, which drove awestruck commentators to speculate on Dou’s process for making such beguiling images. The artist’s demonstration of skill in replicating the shimmering fabric of a silk curtain is complemented by the motif’s associations with excellence and value. Viewers infer Dou’s agency by observing the virtuosic craftsmanship embodied in the pictures and by appreciating the iconographic significance of the pictorial elements. Form and content reinforce one another to underscore the painter’s mastery of his art.

The incorporation of a counterfeit curtain and frame thus transforms the Painter with Pipe into a representation of a collectible work of art.68 Like the allusion to Parrhasios, the reference to the practice of veiling paintings in a collection is directed at a viewer who was accustomed to seeing works displayed under such conditions. As Kemp argues, what these liefhebbers expected from objects in a cabinet were the qualities of “deception, subterfuge, optical illusion, and surprise.”69 Dou’s Painter with Pipe fulfills these requirements admirably. The participation in the social rituals of visiting collections and engaging in conversations about works of art was a means of performing one’s role as a member of the cultured elite. The owners, who were known to control access or the conditions under which the pictures were seen, acted as agents as they showed off ingenious creations in their collections.70 The viewers, meanwhile, proved their regular exposure to such works of art by articulating their appreciation of an art object in accepted terms—as expected of liefhebbers—thus also confirming their status.

Using Gell’s concepts of enchantment and art nexus, this paper has demonstrated how a work of art could act as a conduit for the complex and overlapping relationships between various human agents involved in the practice of collecting. The interaction between a painting like Dou’s Painter with Pipe and an individual viewer took place within a larger cultural framework, where to be enchanted was also to show his or her connoisseurial skill and taste, or, in other words, to make visible his or her social distinction.