In the late Middle Ages, the rugged terrain of the Ardennes, characterized by deep valleys, dense forests, and dramatic rock formations, gave rise to myths and legends that explained its striking natural features. This article incorporates these geomyths into interpretations of landscape paintings by Joachim Patinir and Herri met de Bles. Legendary landmarks from the region’s most prominent saga, the Four Sons of Aymon, appear in their landscapes, including the Rocher Bayard (Bayard Rock) and the Chérau de Charlemagne (Cart path of Charlemagne), recalling the mythologized terrain of the Meuse Valley. As an art historical approach, geomythology offers an interpretive framework that is as attentive to environmental history and local, material knowledge of nature as it is to immaterial and ephemeral traditions once embedded in the terrain.

The low mountain range of the Ardennes Massif extends across northern France, southern Belgium, northern Luxembourg, and western Germany.1 Densely forested, riddled with caves, and carved into valleys and cliffs by the tributaries of the Sambre and Meuse, the Ardennes inspired a rich body of lore in the late Middle Ages to account for its extraordinary—if not forbidding—terrain (fig. 1). Drawing together regional literature such as monastic histories and hagiographies, oral traditions ranging from sung epics to local tales, and practical knowledge of nature, these myths and legends attributed anomalous features of the landscape to a remarkable cast of characters. Quasi-historic figures such as Charlemagne and Saint Hubert mingled with magical beings, including giants, fairies, and dwarfish creatures called nutons.

Landmarks mythologized in the Meuse Valley of the Ardennes, many of which still bear their medieval, if not ancient names, became essential points of reference for travelers and pilgrims crossing the region. Despite its formidable topography, the Meuse Valley was a vital thoroughfare for early modern travelers, and cities such as Dinant, Namur, and Liège flourished as centers of commerce.2 Even as they originated in a local context, legends contributed to impressions of the Ardennes articulated by travelers, historians, and humanists of the sixteenth century.

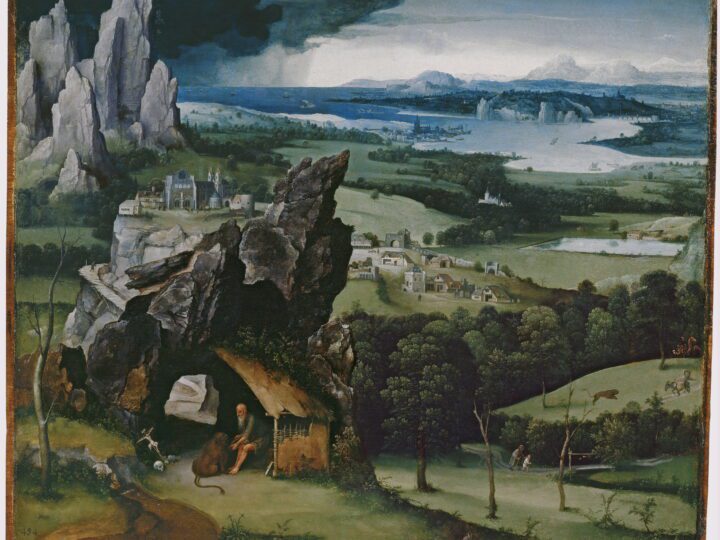

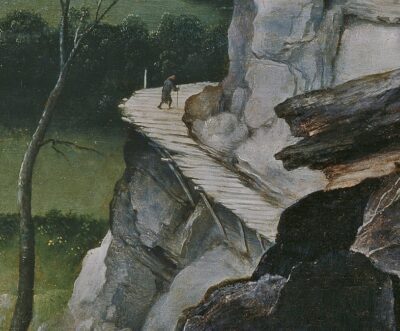

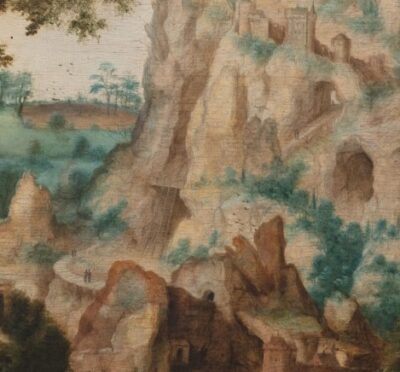

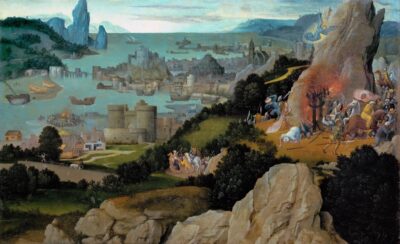

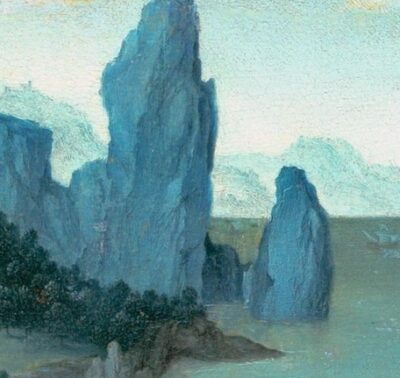

Several legendary landmarks appear in paintings attributed to two painters from the Meuse Valley: Joachim Patinir (ca. 1480–1524) and Herri met de Bles (active ca. 1530–1560). Their landscapes contain numerous references to the region’s most prominent legend, The Four Sons of Aymon (Les quatre fils Aymon in French, De Vier Heemskinderen in Dutch). The distinctive peaks in Patinir’s Landscape with Saint Jerome (fig. 2) recall the flaked limestone and spindly form of the Rocher Bayard (Bayard Rock), a landmark known since at least the fourteenth century (fig. 3).3 The wooden pathway winding through the background evokes the Chérau de Charlemagne (cart path of Charlemagne), a historic passage near Dinant (fig. 4).4 Bles incorporated these motifs as well. Wooden pathways thread through crags in Landscape with the Parable of the Good Samaritan (figs. 5 and 6), while the Bayard Rock appears prominently in Landscape with the Meeting on the Road to Emmaus (fig. 7). Both features were linked to Charlemagne’s pursuit of the Aymon brothers and their enchanted horse, Bayard, a popular subject of medieval poetry that permeated sixteenth-century visual culture.

This essay argues that these motifs enriched paintings for patrons and collectors familiar with the Meuse Valley, activating historical, mythological, and spiritual associations with the landscape. The Four Sons of Aymon addresses moral dilemmas––choices between loyalty and rebellion, exile and redemption––that resonated with religious themes in the works of Patinir and Bles. Invoking the Meuse Valley through landmarks that recalled the legend, these landscapes encouraged viewers to read sacred narratives through a localized frame of reference. The presence of these motifs in painting testifies to a shared conception of landscape that informed the environmental imagination of the painters and their audiences.

The identification of natural landmarks and the geomyths they summoned casts light on a critical moment in Netherlandish art: the rise of the so-called Weltlandschaft (world landscape).5 While representations of landscape appear in fifteenth-century manuscript illuminations and, to a lesser extent, painting, the compositions of Patinir and his stylistic successor Bles marked a turning point for the genre’s development.6 Recent scholarly assessments of the Weltlandschaft have focused largely on the devotional tradition or artistic conventions from which these pictures emerged. While these two approaches offer insight into the anagogical potential of the landscape, as well as the workshop practices and economic pressures of Antwerp’s art market, they have constrained our understanding of the cultural and material worlds these paintings reflect. The prevailing assumption that Patinir and Bles painted wholly imaginary landscapes comprised of generic stock motifs has overshadowed the complex relationship between their art and the environment they inhabited.

I propose a geomythological approach by which to recover this overlooked dimension of meaning. In 1968, geologist Dorothy Vitaliano coined the term to designate myths that account for memorable natural phenomena, particularly geological features. Whether slow processes such as the erosion of cliffs or sudden catastrophes like earthquakes, these events shaped the landscape and inspired myths to explain their origins.7 I use the term here both to identify geomyths as a body of lore that was particularly rich in the Ardennes and to propose a geomythological framework that arises from this material but has applications for other eras of art history. Geomythology offers entry into an authentic historical perspective obscured by current methods of analysis. Contemporaries of Patinir and Bles recognized this tradition of storytelling and prized the painters’ landscapes for their perceived faithful evocations of nature. Patrons and collectors, including the Augsburg merchant Lucas Rem, likely had direct familiarity with the Meuse Valley’s legendary landmarks, increasing their recognizability in painted landscapes.8 These sites were located on major routes, where they served as points of reference and sources of entertainment for merchants and pilgrims.

This essay offers a new strategy for interpreting landscape painting, and with it new insights into how premodern audiences perceived and interacted with the natural world. I begin by clarifying and situating geomythology within the historiography of Netherlandish landscape painting, addressing its challenges and refinements as an experimental approach. I then examine the Meuse Valley as a cultural landscape, tracing the origins and significance of its most formative legend, the Four Sons. In the second half, I connect geomyths of the Ardennes to the landscapes of Patinir and Bles. Demonstrating the ways natural motifs in their pictures relate to landmarks associated with the Four Sons, and comparing their treatment across each master’s oeuvre, I show how invocations of the Ardennes prompted viewers to ponder the interrelation of localized narrative and biblical subject.

Geomythology and the Historiography of Netherlandish Landscape Painting

Little is known about the lives of Patinir and Bles, save for their shared origins and stylistic similarities. Both painters emigrated from Dinant-Bouvignes, neighboring cities on opposite sides of the Meuse in the Ardennes, to Antwerp. Patinir enrolled in the city’s Guild of Saint Luke in 1515 and maintained a successful workshop until his death in 1524. Bles is probably the “Herry de Patinier” who enrolled in the same guild in 1535; he may have studied under Patinir or even been related to him, but there is no textual evidence to confirm either claim.9

The historiography of Patinir’s innovative compositions has oscillated between material and topographical readings and metaphorical interpretations. While both perspectives contribute to our understanding of these pictures, they have produced a conceptual divide that was likely foreign to premodern sensibilities, in which symbolic meaning converged with geographic specificity. We need an integrative framework: one that accounts for the ways early modern viewers understood these landscapes as simultaneously allegorically and literally grounded.

During the painters’ lifetimes and in the following decades, collectors across Europe valued Patinir and Bles for their depictions of natural scenery. Spanish humanist and art theorist Felipe de Guevara, who owned several paintings by Patinir, praised him in 1556 for immortalizing a shipwreck he had witnessed.10 In his painters’ biographies of 1572, the Flemish poet Dominicus Lampsonius credited Patinir’s heightened appreciation for nature to his upbringing in Dinant.11 Italian collectors also admired the masters for their attention to natural detail; Karel van Mander wrote in Het Schilder-Boeck (The painter’s book) of 1604 that Bles’s works were commonly found in Italy, where he was nicknamed civetta for his hidden owl motif.12 Writing in 1548, the Venetian painter Paolo Pino was referring to Patinir and his successors when he credited northern landscape painters for their ability to capture the wild scenery of their homeland, in contrast to the “tame garden” of Italy.13

Well into the twentieth century, art historians treated these landscapes primarily as depictions of the Meuse Valley, even identifying some of the same landmarks explored in this essay. In 1863, Alfred Bequet noted the affinity between the Bayard Rock and formations in Bles’s Landscape with a Peddler Robbed by Apes, observing that the horizon line resembled the bluffs around Dinant (fig. 8).14 At least three scholars recognized the wooden pathway of the Chérau de Charlemagne in the backgrounds of both painters, citing the motif as evidence of local inspiration.15 Their observations were largely descriptive, however, and did not prompt deeper inquiry into the role of topographic specificity in early modern interactions with these works.

Scholarship has since shifted toward anagogic interpretations of Patinir’s compositions, the outcome of a broader trend toward iconographic interpretation in late-twentieth century scholarship. Reindert Falkenburg traced his style to the Andachstbild, devotional imagery intended to facilitate prayer, and argued that Patinir’s landscapes guided viewers’ spiritual reflection. Their natural contrasts—rugged mountains and verdant plains, stormy skies and calm clearings—functioned as metaphors for the spiritual journey of the Christian pilgrim, visualizing the moral choice between virtue and vice.16 Michel Weemans has examined the landscapes of Bles as inflections of the Christian concept of the metaphorical Book of Nature, suggesting that the anthropomorphic qualities of his compositions encouraged a type of visual exegesis in which viewers discerned divine meaning in the natural world, a reading influenced by the metaphor’s popularity during the Protestant Reformation.17 Scholars have also examined the ways Antwerp’s competitive art market influenced Patinir’s style.18

These symbolic and market-driven interpretations have enriched our understanding of how landscapes functioned as sites of spiritual contemplation and as reflections of economic forces that shaped painters’ practices. Earlier references to local topography, however, have been sidelined in the process. Walter Gibson, for instance, acknowledged the striking resemblance between Patinir’s peaks and the Bayard Rock but ultimately ascribed them to a broader vogue for exoticizing geological formations, already evident in works by Quentin Massys and other Antwerp masters, particularly the natural arch motif in Massys’s Sorrows of the Virgin altarpiece (1509–1511; Museu Nacional De Arte Antiga, Lisbon).19 Simon Schama similarly characterized Patinir’s landscapes as signifiers of the otherworldly, describing them as expressions of the “transformation from a domestic to an exotic spirituality,” a perspective reiterated in later studies.20 Patinir undoubtedly drew inspiration from the inventive perspectives and topographies of contemporaries like Massys and predecessors such as Hieronymus Bosch. However, there is a tendency to group realistic geological motifs such as the Bayard Rock with obviously fantastical ones such as the rock arch, under the umbrella of artistic formulae, thereby overlooking legitimate references to real-world environments.21

The resulting presumption in the current scholarship is that symbolic intent and topographical accuracy could not coexist within these early landscapes. Earlier identifications of Ardennes landmarks have been dismissed as the regionalist nostalgia of nineteenth-century Belgian historians, while scholars characterize early modern admiration for Patinir’s landscapes as naïve, suggesting that foreign audiences mistakenly saw stylized compositions as literal topographical views.22 But early viewers were acquainted with the Ardennes through historical-geographies, pilgrimage itineraries, and literary epics, all of which contributed to a complex environmental imagination––material that will be addressed in the next section.

This essay builds on recent efforts to incorporate site-specificity and materiality into the study of premodern culture. Art historians have explored the ways individuals and painters responded to their physical environments, with a particular focus on the mediating role of sacred landmarks and pilgrimages.23 On the side of environmental history, research dedicated to the Ardennes, such as Ellen Arnold’s work on monastic topography, brings new light to the relationship between ecological practices and identity formation in the late Middle Ages.24 These interventions are the basis for my proposed framework, which bridges the conceptual and experiential dimensions of the Ardennes.25

Geomythology is useful first because it names a practice, rather than a specific narrative structure: that is, creative explanations for unusual terrain features or natural events.26 Constituted by such varied sources as regional hagiographies, courtly poetry, and natural knowledge, the lore of the Ardennes defies modern distinctions between myth, legend, and folktale.27 Moreover, these traditions did not emerge from strictly vernacular or learned contexts. In fact, the lore that emerged in the sixteenth century was mutually informed by “official” sources, such as monastic histories, and by local adaptations that creatively riffed on those sources. In turn, these local legends crossed into erudite and humanist circles as chroniclers, travelers, and antiquarians recorded regional beliefs. Rather than presuming an elite understanding of scholarly symbols, this method relies on legends and landmarks that transcended social divisions and were familiar to both rural and urban viewers.28 Finally, geomythology is especially well suited to the Ardennes. In “Legends of the Ardennes Massif” (2021), one of a handful of geologic studies to make rigorous use of geomythology, the authors surveyed various legends attached to natural curiosities in the Meuse Valley.29 This systematic presentation of lore lays the groundwork for our reassessment of landscapes by Patinir and Bles.

While geomythology refocuses attention on a neglected cultural landscape, it requires some refinements to accommodate the peculiarities of late medieval lore.30 Vitaliano’s definition was concerned primarily with major geological processes, but many Ardennes legends explain smaller-scale features, such as irregular striations or rock depressions. The scope of the term could be narrowed to account for these less drastic natural phenomena. Second, geomyths are generally associated with natural sites exclusively. In premodern lore, however, natural and human-made sites were not sharply differentiated. Megaliths, ancient roads, and ruined fortresses could function in the same way as natural sites, anchoring the terrain to a distant, mythic past.31 In this essay, two such landmarks, the Chérau de Charlemagne and the ruins of the settlement of Poilvache, exemplify this hybrid category, alongside natural features such as the Bayard Rock.

This mingling of natural and constructed landmarks is apparent in early modern sources. In 1549, Spanish humanist Juan Cristobal Calvete de Estrella (ca. 1510–1593) documented his journey through the Meuse Valley while touring the Netherlands as tutor to the future King Philip II (r. 1556–1598). Detailing the origins of Namur and Dinant, Calvete de Estrella attributed their locations to a topography molded by ancient pagan forces, linking Dinant to the goddess Diana.32 The Italian merchant Lodovico Guicciardini (1521–1589), who settled in Antwerp in 1541 and may have known Bles, recorded a similar explanation, specifying that the city was once the site of a former temple dedicated to Diana in his Descrittione di tutti i Paesi-Bassi (1567).33 Such sources shed first light on how early modern audiences perceived the Ardennes as a layered cultural landscape that did not always distinguish natural and human artifacts within historical narratives. We now turn to that landscape.

The Meuse Valley as a Cultural Landscape

As they descend toward the Meuse, numerous tributaries from the forested highlands have etched their mark, carving networks of caves, sinkholes, and gorges over millennia.34 This dramatic landscape inspired a long tradition of storytelling that sought to explain the challenging territory and, conversely, sought to situate human history on a broader cosmological timeline. Legends that emerged from the Ardennes’ landscape in the Middle Ages persisted in the imaginative geographies of both painters and their audiences. The most enduring tales cast the Ardennes as both a place of refuge and a site of danger, an interplay later reflected in the paintings of Patinir and Bles.

Stories about the Ardennes’ rugged topography drew from multiple strands of lore rooted in the Merovingian and Carolingian eras. One of the earliest recorded impressions, already articulating themes that would persist into the sixteenth century, appears in Julius Caesar’s first-century BCE Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), in which he describes the Arduennam Silvam (Ardennes forest) as a wilderness “full of defiles and hidden ways” that sheltered his enemies and obstructed his troops.35 The first monasteries established in the region, particularly Stavelot-Malmedy (founded in 648 CE) and later Saint Hubert (in 825 CE), cultivated the forest’s reputation as a forbidding and impenetrable space, even a haven of pagan idolatry.36 When the Benedictine abbot Remacle (d. 673 CE) arrived at the forest designated for Stavelot-Malmedy’s foundation, he found signs of idolatry in the nearby springs, the so-called lapides Dianae (stones of Diana).37 Remacle exorcised the demonic spirits polluting the springs with the sign of the Holy Cross, establishing the fons Remacli (Spring of Remacle) that enabled the monks to build their monasteries.38 Saint Hubert (ca. 656–727 CE), the other so-called “Apostle of the Ardennes,” who underwent his own conversion in the forest, went on to convert the region’s remaining pagans, as told by the Counter-Reformation theologian Joannes Molanus in his Natales sanctorum Belgii (Native saints of Belgium) of 1595.39 For Remacle and Hubert, the Ardennes was at once a pastoral antidote to the temptations of civilization and a dangerous pagan wilderness that tested Christian faith.40 Monastic histories and hagiographies codified an early perception of the Ardennes as a paradoxical space: both a refuge and an ordeal, the forest offered asylum from society while threatening to strip away the very conditions that foster reason and humanity.

Even as the official hagiographies of Remacle and Hubert were modified according to local customs, they preserved this enigmatic impression of the Ardennes. In 1575, the renowned cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598), while traveling from Antwerp to Trier, recorded an unofficial explanation for Stavelot’s name: the devil, disguised as a wolf, tried to sabotage Remacle’s construction of the abbey by killing his donkey, only for the saint to compel the wolf to take its place. This miraculous triumph, Ortelius wrote, accounted for the name “Stablo,” derived from stabulum luporum (stable of wolves).41 Tales like this one perpetuated a vision of the Ardennes as a wilderness that was both hostile and redemptive; the same conditions that permit demonic forces to undermine order hold the promise of divine intervention. For visitors like Ortelius, landmarks offered literal testimony to this vision; travelers observed the remnants of the lapides dianae in springs and saw impressions of pas Remacle (Remacle’s footsteps) in stones that commemorated the saint’s banishment of cult worship.42

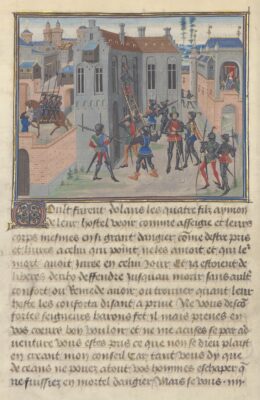

While the monastic lore contributed one layer to the cultural landscape of the Ardennes, it was inseparable from another: the chanson de geste (song of heroic deeds), the lyrical poetry of French troubadours. These sung epics originated in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, but their afterlife was long; they were transcribed and condensed into prose in the late Middle Ages. One of the oldest and most popular epics, the Chanson de Renaut de Montauban, follows the rebellion of the knight Renaut (Renault, Renaud) and his three brothers against the Emperor Charlemagne (748–814). In the fifteenth century, the Chanson de Renaut de Montauban was converted into a chivalric romance that quickly circulated around Europe in print: Les quatre fils Aymon (The Four Sons of Aymon).43

Certain details of the lengthy saga vary between the French Quatre fils Aymon and the Dutch and German versions. The following summary is limited to plot points relevant to the Ardennes episode of Les quatre fils Aymon, which formed the basis for most sixteenth-century translations: the tale begins with the visit of Aymon, duke of Dordogne, to Charlemagne’s palace in Paris with his four sons—Renaut, Alard, Guichard, and Richard—for the Pentecostal feast.44 At first, the sons are well received; when Renaut wins a royal tournament, Charlemagne gives him a horse called Bayard.45 But the emperor’s favor sours when Renaut kills his nephew in a dispute that arises from a game of chess, and the brothers flee the palace in haste, taking Bayard with them. No ordinary horse, the enchanted Bayard is capable of carrying all four brothers on his back. His supernatural origins are connected to a sorcerer named Maugis, a cousin of the four brothers who lives in the Ardennes.46

The four fugitives flee to the Ardennes, and with their cousin’s help they build a fortress along the Meuse called Montessor. The vengeful Charlemagne discovers their hideout, however, forcing the brothers to abandon Montessor and take shelter in the forest. Astride Bayard, whose gigantic size enables him to clear the peaks and valleys of the Ardennes in a single leap, the brothers constantly evade Charlemagne’s grasp. The emperor and his soldiers are always a step behind as they travel by foot through the challenging terrain. The brothers are eventually driven from the Ardennes, and the confrontation between Charlemagne and Renaut takes more twists and turns before culminating in a truce. In exchange for the brothers’ pardon, Renaut must participate in a crusade in the Holy Land and surrender Bayard to Charlemagne. The emperor condemns Bayard to drowning in the Meuse with a millstone around his neck as punishment for abetting the fugitives. Cast off the bridge in Liège, Bayard breaks the millstone, escapes from the river, and flees into the forest. After returning from Jerusalem, Renaut helps build Cologne’s Cathedral of Saint Peter, but his superhuman strength and refusal of wages provoke jealous masons to kill him. His miraculously recovered body is later enshrined in Saint Reinold’s Church in Dortmund.

While the Ardennes harbors the brothers from Charlemagne, it is a cruel refuge, exacting a dehumanizing toll through its harsh conditions.47 The Aymon brothers suffer from bad food and poor water, rain, wind, hail, and a constant dampness that causes the men’s clothes to deteriorate and every shelter they build to fall apart. In exchange for protection, the brothers forsake civilizing comforts for a period of seven years, described in the epic as one long winter. It is spring when the brothers leave the forest in despair, seeking their mother in Dordogne. When they arrive at their mother’s home, the sons are unrecognizable, resembling hermits or beggars.48 The Ardennes emerges once more as a space of contradiction, offering both sanctuary and suffering. Survival demands resilience, and hardship fosters transformation. These tensions were inscribed in the landscape itself, as natural features acquired legendary status testifying to the brothers’ plight.

Legendary Landmarks: The Four Sons of Aymon in the Ardennes and the Painted Landscape

Although the setting of the Four Sons shifts from Dordogne to the Ardennes and Cologne, no region bears its imprint more strongly than the Ardennes. Many of the landmarks that commemorate Charlemagne’s pursuit of Bayard and the Aymon brothers are still visible today. Millstones, megaliths, and flat stones believed to be the giant horse’s hoofprints are called pas Bayard (Bayard’s hoofprints). In the early twentieth century, these pas Bayard were still known in Berthem, Buzenol, Chiny, Couillet, Dolembroux, Oppagne, Pepinster, Remouchamps, and Wéris.49 Three sites in and around Dinant-Bouvignes—the Bayard Rock, the Chérau de Charlemagne, and the ruins of Poilvache—bear associations with the Four Sons, and all three appear in the landscapes of Patinir and Bles. Connecting these landmarks to their painted counterparts establishes a basis for deeper inquiry into how viewers enlisted these motifs to construct meaning.

Travelers approaching the cities via the Meuse would encounter the Bayard Rock south of Dinant, pulling away from the cliffs like a rocky forefinger (see fig. 3). Named in the archives of Liège as early as 1355 as a reference point for a nearby wood, the Bayard Rock was said to be split by the powerful hoof of the horse as he ferried the brothers across the river.50 This may be the same rock mentioned in a fifteenth-century edition of Les quatre fils Aymon, which describes a large crag on the Meuse as Bayard’s resting place, called the Rocher Bayard by local merchants and pilgrims.51 Such elongated crags are among the most notable features of Patinir’s landscapes, where they consistently quote the size, shape, and setting of the Bayard Rock. The sharp rupture of one shorter peak from a larger bluff appears repeatedly among rocks painted close to the water’s edge, as in Patinir’s Landscape with Saint John the Baptist Preaching, purchased by Rem when he visited Antwerp between 1516 and 1517 (figs. 9 and 10). In the same artist’s The Wheel Miracle of Saint Catherine, the rocky protuberance pulls away completely from the riverbank, still approximating the peak as it splits from riverbank cliffs (figs. 11 and 12). Sometimes this form appears inland, as in the Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (ca. 1550; National Gallery, Washington, DC) after Patinir, a composition apparently adapted by Bles for his Landscape with the Meeting on the Road to Emmaus (see fig. 7). In every case, the flaked texture and streaked coloring of the rocks match the limestone crag on the Meuse.

A second landmark attributed to the Four Sons was once located in the valley of Leffe near Dinant (fig. 13). Here traces remain of the Chérau de Charlemagne, an ancient wooden pathway built to navigate horses and carts through the steep ravine. This history is reflected in the modern name of the road that runs parallel to the valley floor into Dinant: the Charreau de Leffe, derived from the Walloon word for cart (chèrète).52 Archaeological studies of the markings visible in Leffe’s rocky escarpment at the beginning of the twentieth century indicated the medieval pathway was constructed from flat wooden planks that projected horizontally from the cliff face to create a smooth gradient; these were supported from below by beams inserted vertically into the rock.53 Over time, the chéreau and a nearby spring at the ravine’s summit acquired geomythical significance. According to local lore, without the aid of Bayard to ferry them over Leffe’s ravine, Charlemagne’s soldiers and their horses were forced to descend into the valley and erect a path to climb the opposing slope, where Charlemagne struck a rock to produce water for his troops.54 Uniquely adapted to the Ardennes’ rugged landscape, the Chérau de Charlemagne, so named since at least the fourteenth century, is one of several examples of wooden cart paths between Dinant and Namur commonly called chéraux.55

Once identified, the wooden pathway emerges as a recurring motif in the backgrounds of paintings by Patinir and Bles, rendered with striking uniformity. The walkway’s distinctive construction is clearly visible in Patinir’s Landscape with Saint Jerome: the path that circles the mountain behind Jerome’s shelter is made of wooden planks, upheld by beams inserted into the stone at regular intervals (see figs. 2 and 4). A figure, presumably a pilgrim with a walking stick, follows the path around the corner, where it curves out of sight. In The Temptations of Saint Anthony (fig. 14), a solitary figure navigates the elevated wooden platform that hugs a crag in the left background (fig. 15). Rarely does the motif appear without people, either single figures or pairs, making use of it; it is often the sole means by which figures––and the viewer tracing their progress visually––can traverse the rocky passages of the background. Bles’s Landscape with the Parable of the Good Samaritan (see fig. 5), for example, takes the wandering eye on a winding journey through a path that begins in the foreground, following the priest and Levite who have passed and forsaken the robbed traveler. The path continues at the foot of a rocky mass in a series of chéraux, circling around a bend, passing beneath a stone arch, and ending at the summit (see fig. 6).

In addition to these examples, the chérau motif appears in at least seven other pictures attributed to Patinir, and another six to the master and his workshop.56 Once Patinir introduced the motif into his paintings in Antwerp, it occasionally wound its way into the landscapes of masters familiar with his compositions.57 It appears with the greatest consistency and the least modification in the works of Bles, in at least eight attributed pictures, including two versions of the Landscape with Saint Jerome in Namur (figs. 16 and 17). In 2023, conservation treatment of Bles’s Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes (ca. 1535–1550), also in Namur, revealed, beneath overpaint added at an unknown time after its creation, a wooden pathway that resembles the previous examples.58

A third site near Dinant is also connected to the Four Sons: the ruins of the medieval fortress of Poilvache, which overlooks the Meuse a few kilometers north of the Bayard Rock in Houx. Perched atop a rocky promontory, the fortress was dismantled in 1430 and mythologized as the remnants of the brothers’ Montessor retreat (fig. 18).59 Round towers and high-walled fortresses or monasteries crown numerous peaks in the mountainous backgrounds of Patinir and Bles, evoking the fortress ruins identified as Montessor not only in Dinant but in several other towns along the Meuse. Aywaille, Awirs, Dhuy, and Remouchamps claimed the title for their abandoned hilltop castles, a practice that must have familiarized travelers with the regional moniker.60 This motif often crops up alongside the Bayard Rock or chéraux (or both), as in The Penitence of Saint Jerome triptych at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 19). In the background of the triptych’s center panel, a fortress is set in a cluster of rocks that come close to the distinct form of the Bayard Rock (fig. 20).

Each landmark—the Bayard Rock, the Chérau de Charlemagne, and the ruins of Montessor—commemorated the clash between Charlemagne and the Aymon brothers in different ways, but all three affirmed the legend’s central themes of refuge and resistance to imperial authority. The Bayard Rock signified the supernatural power that protected the four brothers, while the chérau preserved the emperor’s interventions in the landscape to suppress rebellion. The ruins of Montessor testified to the brothers’ retreat and self-defense. The painted landscape reflects this dynamic: these motifs do not appear in isolation but in tandem, unfolding across the composition much like they were encountered in the physical terrain.

Just as travelers moving through the Ardennes met these landmarks in sequence, each marking a stage in the story’s contested geography, their arrangement in painting conjured an embodied experience of place. In Bles’s Landscape with the Meeting on the Road to Emmaus, an elevated wooden walkway rises from the valley floor to meet the monastery or castle in the middle ground (see fig. 7). This pairing of motifs, namely the chérau and Montessor, leads the viewer’s eye through the terrain, following the disciples in their journey to revelation. In the foreground, the disciples converse with Christ along a path that winds between two spindly rocks, recalling the distinctive form of the split Bayard Rock.

The same configuration occurs in Patinir’s Landscape with Saint John the Baptist Preaching purchased by Rem, the merchant-patron from Augsburg (see fig. 9): to the right of the Bayard Rock on the water’s edge, a stone structure overlooks the winding river in the background (fig. 21), replicating the position of Dinant’s fortress above the Meuse. Notably, technical study of this picture found that several details were painted over at a later date, including a rectangular, balcony-like formation beneath the hilltop structure that must have resembled the chéreau.61 The occurrence of these motifs in a painting owned by the Augsburg merchant puts them in direct dialogue with a viewer who had intimate knowledge of the Ardennes.

Rem, one of the only known patrons of Patinir, frequently traveled through the Meuse Valley on his journeys between his home city of Augsburg and Antwerp. His Tagebuch, the diary in which he chronicled his movements and business dealings from 1494 until his death in 1541, offers a rare glimpse into the lives of the traveling merchant class. Rem recorded three stays in Namur between 1512 and 1518, the years he likely purchased four paintings from Patinir that bear his coat of arms.62 Given Dinant’s position just upstream along the Meuse, less than 20 kilometers from Namur and directly connected by river and road, it is highly likely that he either passed through or was well acquainted with the city. By the sixteenth century, the Meuse Valley was an economic and industrial corridor, particularly for iron refining and copperware objects (called dinanderies) produced by manufactories at Dinant-Bouvignes.63 Rem’s Tagebuch is unusual as a surviving firsthand account, but his travels were representative of the wealthy, well-traveled collectors that fueled the Antwerp art market.

Landmarks tied to the Four Sons served as key points of orientation for itinerant merchants and pilgrims to the monasteries of the Ardennes. Travelers navigating the Meuse toward Namur encountered the Bayard Rock and Montessor’s ruins overlooking the river, while overland visitors made use of the chéraux. While these specific examples evince local inspiration for Patinir and Bles, they are but a few among a vast network of geomythic sites that characterized the topography of the Ardennes for both inhabitants and visitors. There was little chance of avoiding the region for anyone traveling from western Germany or eastern France to major cities such as Brussels, Ghent, or Antwerp. Moreover, a limited number of ancient routes directed trade and pilgrimage through Dinant, Namur, and Liège, thereby familiarizing travelers with topography through repeat encounters. For merchants such as Rem, these sites were not inanimate signposts. As sources of speculation and storytelling, these landmarks transformed the Four Sons from a literary tradition into a lived topography, which activated cultural references, moral dilemmas, and political and historical mythologies associated with the legend.

The Four Sons of Aymon in the Netherlandish Imagination

The legend of the Four Sons left an extraordinary, if underrecognized, imprint on European visual and literary culture. Essentially a legend of rebellion centered on Charlemagne’s struggle to assert imperial authority over the Aymon brothers, its themes were appreciated far beyond the Ardennes. The Four Sons permeated nearly every facet of late medieval life, from city streets and devotional imagery to festive processions and children’s games. Beyond the Netherlands, it left its mark on urban landscapes, religious traditions, and artistic production throughout Europe. Most important, impressions of the Ardennes conveyed by the Four Sons contributed enormously to perceptions of the region as an enigmatic wilderness.64

Although they took different forms than the landmarks of the Meuse Valley, references to the Four Sons were commonplace in the urban centers of Europe. Houses, taverns, and breweries in cities such as Paris, Brussels, and Mons bore signs of the brothers riding Bayard. Streets named after the Four Sons are documented in 1428 in Namur and 1442 in Liège, appearing later in Spa, Huy, and Dinant.65 In Antwerp, not far from Patinir’s studio, a house on Steenhouwersvest called De Vier Heemskinderen (The Four Sons of Aymon) housed the printers Symon Cock and Gerhardus Nicolaus in 1523, overlapping with the painter’s active period.66

The tale was not confined to static place names or tavern signs; Bayard and the brothers were among the most celebrated figures in Flemish ommegangen (processions) and feast days. Immense horse-shaped floats appear as early as 1416 in Mechelen, and were regularly featured between 1430 and 1530 in Oudenaarde, Eindhoven, Dendermonde, Ath, Bréda, Bruges, Namur, and Brussels.67 In Namur, a 1528 city record notes a payment to a master painter for decorating its Bayard float.68 These processions drew a wide cross-section of society––nobles, merchants, clergymen, artisans, and laborers––with painters and craftsmen collaborating on elaborate designs. Descriptions and images of the floats resemble depictions of the Aymon brothers astride Bayard in fifteenth-century manuscripts such as Renaut de Montauban (mid-15th century, Bibliothèque nationale de France) and the Conquestes et croniques de Charlemaine (fig. 22), suggesting an artistic dialogue between painting and procession iconography.69 The float enjoyed lasting popularity; When Archduke Albert of Austria and his wife Isabella visited Brussels in 1615, multiday festivities included a Bayard float whose size and iconographic details correspond to those described in earlier processions across Flanders (fig. 23).70 Often accompanied by short plays and verses, these displays were observed by local and touring spectators.71

Beyond public performance, the legend’s circulation in print extended its reach across Europe. A prose rendition of Les quatre fils Aymon published in Lyon in 1483 was translated into multiple languages, including an English version in 1490 and a German edition in 1493.72 In Germany, the epic had already circulated by 1450 as Reinolt von Montelban oder die Heimonskinder, a Middle High German verse adaptation, as well as a shorter prose version, Histôrie van Sent Reinolt (ca. 1450).73 In Holland, where chivalric romances were rarely published, editions appeared in Gouda in 1489 and Leiden in 1508, drawing from a Middle Dutch version dating to the thirteenth century.74 Italian adaptations of the epic (Rinaldo de Monte Albano) were available in Venice and Naples before 1500, with further editions throughout the sixteenth century.75 The legend also inspired Italian and Spanish dramatists, including Spanish playwright Lope de Vega.76 The breadth of its transmission demonstrates how early modern viewers across Europe, whether Dutch, French, German, or Italian, became familiar with its themes of defiance, exile, and transformation. When Venetian artists such as Pino credited northern landscape painters for their excellence in rendering wild, untamed scenery, their appreciation was perhaps not misguided at all, but rather admiring of the masters’ ability to depict a specific region imbued with narratives that championed those very characteristics.

For all its expressions in everyday life, some secular and some quotidian, the story of the Four Sons remained a vehicle for profound religious and political debates. As a spiritual allegory, the legend availed itself to multiple interpretations touching on themes of forced conversion and religious persecution. In one reading, the confrontation between Bayard and Charlemagne reflects a central feature of monastic lore from Stavelot-Malmedy and Saint Hubert: the enduring tension between Christian order and pagan defiance. It is, for example, a Christian pilgrim from Stavelot who alerts Charlemagne to the whereabouts of Bayard and the Aymon brothers after spotting them in the forest.77 Bayard’s association with the sorcerer Maugis, moreover, imbued the legend with themes of witchcraft and dark magic.78 Historians have associated Bayard’s escape with anxieties over the persistence of pagan traditions in the Ardennes and compared Maugis to the forest’s forgotten Druids, memories of which lingered in the hagiographies of Remacle and Hubert.79 It is no coincidence that the final lines of a chanson closely related to the Four Sons, “Maugis d’Aigremont,” claim that Bayard’s neigh still resounds through the Ardennes on the feast of Saint John, which falls on the sacred Celtic summer solstice.80

Not all religious interpretations cast Bayard and the brothers as adversaries to Christian order. Jean-Baptiste Gramaye, writing in 1607, recorded that the town of Bertem near Louvain honored Saint Adelard, believed to be one of the Four Sons.81 The town bore his coat of arms and displayed his crib, and the nearby forest of Meerdael (once contiguous with the Ardennes) preserved one of Bayard’s hoofprints. Adding to these observations, the theologian Molanus also mentioned an altarpiece in Bertem depicting the brothers kneeling with Bayard.82 A remarkable testament to a visual tradition in devotional painting, the altarpiece presented the brothers not as rebels but as pious figures worthy of imitation. From this perspective the brothers occupy the moral center of the legend, as Christian martyrs subject to Charlemagne’s vengeful authority.

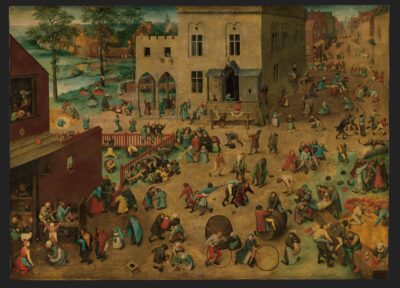

Disputes around the virtue of the Four Sons extended into children’s literature and devotional discourse. Despite its adult themes, the legend was evidently popular among children: the group riding a hobby horse in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Children’s Games has been identified as a reference to the tale (figs. 24 and 25).83 These playful encounters were occasionally at odds with moral concerns. In his primer on manners, Erasmus discouraged children from reading the Heemskinderen in favor of religious texts.84 However, some clerics may have valued the legend for its illustration of moral relativity. Marginal annotations and underlined passages in a surviving copy of the Historie vanden vier Heemskinderen (Leiden, 1508) indicate the book belonged to a minister who mined the text for his sermons.85 The charming children’s graffiti depicting the brothers astride Bayard in paintings of church interiors, including Pieter Saenredam’s Interior of the Buurkerk at Utrecht (fig. 26) and Emanuel de Witte’s (1617–1692) Interior of the Oude Kerk in Delft with the Tomb of Piet Hein (mid-17th century; Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium), could allude to the persistence of these debates in the seventeenth century, perhaps acquiring new resonance in the wake of the Reformation as an emblem of resistance to Catholic authority.

The dilemmas posed by the Four Sons—loyalty and insubordination, duty and disobedience—did not exist in abstraction but were embedded in the physical landscapes in which the story took place, where rebellion was a political reality. In the Ardennes, resistance took the form of dissent and opposition to ecclesiastical authority, as rulers sought to consolidate control over autonomous cities and religious principalities. Charlemagne is repeatedly undermined in the Ardennes, an inversion of power that finds parallels in later mythic outlaws of the forest, such as Robin Hood, who rebelled against King Edward I of England (r. 1272–1307).86 The contested status of rebels has something in common with the mythical Wild Man, the antithesis of the courtly ideal who ostensibly once populated the forested fringes of society throughout Europe and was most elaborately mythologized in the Harz mountains.87 But the inhabitants of Dinant and Liège were uniquely sympathetic to the antihero status of Bayard and the four fugitives. The brothers’ evasion of Charlemagne and Bayard’s final escape in Liège anticipated the city’s resistance to Philip the Good (r. 1419–1467), who sought to absorb the Prince-Bishopric of Liège into the Burgundian Netherlands in 1465. The largest city in the Ardennes, Liège revolted three times––twice suffering near-total destruction by Philip’s troops––before regaining independence in 1477. Likewise, in response to an uprising in Dinant in 1466, Philip and his son Charles the Bold (r. 1467–1477) punished the city’s burghers by casting them into the Meuse and sacking the city on a scale that required decades to repair.88 The legacy of these devastating rebellions persisted in both the urban landscape and the social memory of these cities in the sixteenth century.89

The popularity of the Four Sons beyond the Low Countries implicates the legend in a broadly shared conception of the Ardennes as a wilderness steeped in history, conflict, and legend. Traditions of the Ardennes, from the hagiographies of Remacle and Hubert to the Four Sons, cast the forest as a space of contrasts: an escape from moral temptation and oppressive rule as well as a site of hardship and transformation. The distinctive terrain of the Ardennes played a constitutive role in this impression; the legend was not only an intellectual or allegorical tradition but a deeply embodied one. Civic traditions, processions, and urban topography across the Netherlands continuously renewed themes of refuge, revolt, and resilience. More than a source of entertainment, the Four Sons resonated with current concerns, from religious devotion and children’s instruction to anxieties about tyranny and rebellion.

For patrons and collectors familiar with the Ardennes, mythologized landmarks added an experiential element to what must have been a rich and complex conception of the Four Sons. Beholders brought this knowledge to bear on their interpretations of landscape paintings by Patinir and Bles. In the same way that passing through the Meuse Valley activated its legendary significance, recognizing prominent landmarks as motifs in landscape paintings evoked a repertoire of personal associations and collective memories. Having identified landmarks associated with the Four Sons in the painted landscape and traced the legend’s reach across time, place, and social strata, we shift now to its significance in the paintings of Patinir and Bles.

Interpreting the Geomythic Landscape: Trials, Exile, and Transformation

Motifs associated with the Four Sons in painted landscapes availed themselves to viewers as a local framework for constructing meaning through references to the Ardennes. While their recurrence across multiple compositions owes something to the conventions of artistic workshops, the fact of their presence across these landscapes, and the consistency with which they appear in the works of two painters from Dinant-Bouvignes, demands closer scrutiny. How did these landscapes convey themes embedded in the cultural landscape of the Meuse Valley to contemporary viewers?

We know little about the way liefhebbers (art lovers) apprehended these landscapes and the kinds of meaning they inferred from them; this uncertainty makes them sites of rich interpretive inquiry. But one contemporary insight into the way audiences approached paintings comes from Van Mander’s Het Schilder-Boeck, in which the author describes viewers placing bets on how long it would take them to spot the “kakker,” a squatting, defecating figure hidden in Patinir’s landscapes.90 Van Mander’s anecdote brings to mind a lighthearted, collaborative viewing experience.91 As a whole, the landscapes of Patinir and Bles may have served a Christological narrative, but their constituent parts availed themselves to an open-ended form of storytelling that drew on deeply familiar associations, local histories, and wit. In the same way that viewers spotted hidden figures and speculated on their meanings, the identification of motifs such as the Bayard Rock or the Chérau de Charlemagne would have prompted viewers to reflect on their contributions to the main narrative.

The prominence of the Four Sons in civic pageantry, manuscript illuminations, and festival traditions suggests painters engaged frequently with the legend and its iconography. In addition to participating in the festivities themselves, artists were enlisted by cities to visit neighboring towns, observe their processions, and design and decorate floats accordingly. Likewise, manuscript illuminations depicting the legend circulated in noble collections, serving as artistic inspiration. Because Patinir and Bles hailed from the region most closely associated with the Four Sons, they were likely aware of Dinant-Bouvignes’s most recognizable landmarks and their associations, if not also the visual and performative dimensions of the legend.

Even where motifs do not represent exact one-to-one correspondences with the physical landmarks, their significance lies in the interplay of multiple references and the recognizability of essential forms; together, they summoned the Ardennes. If late medieval pilgrims mapped sacred histories onto real-world terrain, these pictures encourage a similar exercise in reverse: viewers mapped firsthand experience, natural knowledge, and social memory onto the painted landscape to create meaning. While the associations that emerged from this process were numerous and unique to the individual, I propose three interrelated interpretive categories activated by allusions of the Ardennes: the wilderness as a site of spiritual transformation, a space of journey and exile, and a domain of inversion and disorder.

The first category encompasses one the most frequently depicted subjects of Patinir and Bles: the hermit saints Jerome, Anthony, and John the Baptist, who sought trial and spiritual renewal in the wilderness. Their tribulations correspond to longstanding hagiographic traditions in the Ardennes, particularly the lives of Remacle and Hubert, who ventured into the “untamed” forest to establish their monasteries. The Ardennes of the Aymon brothers has the same qualities: the brothers find sanctuary in the forest but undergo a transformation, emerging after seven years in the wilderness resembling haggard hermits more than knights.

In the landscapes of Patinir and Bles, these tests of faith materialize in the isolated retreats and rocky abodes of the hermit saints. In Patinir’s Landscape with Saint Jerome, the saint, clothed in rags, tends to his injured lion beneath a rock formation and a shelter of wood (see fig. 2). The structure shows signs of decay; a crumbling wall exposes a wattle fence, and the roof bears cracks, recalling the destructive effects of the Ardennes climate, which brought down every shelter the Aymon brothers built after they fled Montessor. In the background, the previously identified wooden chérau reappears, alongside a cluster of peaks to the left that evoke the Bayard Rock. To the right, similar rock formations stand at the water’s edge.

The same configuration of motifs in Patinir’s The Temptations of Saint Anthony highlight the physical deprivation and inner turmoil brought about by the wilderness (see fig. 14). Saint Anthony suffers alone in the desert, beset by grotesque visions that challenge his resolve. The concept of the desert is abstracted here to resemble the wilderness of the Ardennes, signified by landmarks that recall similar deprivations experienced by the Four Sons. In the left background, behind a ruinous monastery atop a rocky promontory, jagged mountains and twisting pathways pose a daunting journey to the solitary figure traversing the wooden chérau circling one of the peaks. Dark clouds gather over the distant mountains and a riverside settlement, reminiscent of Dinant or another city on the Meuse. The lone pilgrim who traverses the wooden walkway is entering into a contest that is as much about mental as physical endurance, not unlike the saint in the foreground. For their part, the Aymon brothers are constantly pursued and betrayed in the isolation of the forest. Their trials, like Anthony’s, are not exclusively physical; they experience self-doubt and despair as they confront forces that threaten their autonomy.

At the same time, the wilderness in each case is a crucible for spiritual reckoning and, ultimately, redemption. Anthony’s solitude distances him from the temptations of the world, and the Aymon brothers’ flight removes them from the court, a space of power and prestige but also of volatility and temptation. Renaut, overcome by emotion, struck down Charlemagne’s nephew at Charlemagne’s palace, thus setting their exile into motion. In effect, the landscapes of Jerome and Anthony stage the paradoxical impression of the Ardennes that was codified in monastic lore and The Four Sons of Aymon: the forest as a necessary but trying antidote to society’s ills. Such allusions were not purely symbolic. Viewers who understood the real perils of crossing the Ardennes—where steep ravines, dense woodlands, and ancient roads made travel an arduous and often hazardous undertaking—recognized the extremities presented in these pictures.

References to the challenging climate held additional significance for merchant-patrons like Lucas Rem. Rem’s 1516–1518 trips to Antwerp, the visits linked to his purchase of paintings such as the Landscape with the Preaching of Saint John the Baptist (see fig. 9), brought him through the Ardennes days before he would have visited Patinir’s studio.92 It is worth noting that in addition to the Preaching of Saint John landscape, Rem purchased another featuring the penitent Jerome in the wilderness. In this picture, the hermit shelters beneath a crag overlooking a valley below, where a river winds through boulders and disappears between hills topped with the silhouettes of distant structures (fig. 27). Travelers along the Meuse, such as Rem, encountered these very sites: the Bayard Rock, the ruins of Montessor, and the overland chéraux, each instilled with mythic and historic significance.93 Not simply elements of local lore, the landmarks were points of orientation in a region that could just as easily offer refuge as it could spell disaster.

A second interpretive category emerges from these considerations: the Ardennes as a space of journey and exile. Patinir and Bles favored subjects that present figures at a remove from civilization, navigating uncertain terrain in a moment of transition or revelation. Bles’s Landscape with the Meeting on the Road to Emmaus, where all three landmarks of the Four Sons appear, portrays the scene from the Gospel of Luke in which two disciples encounter Christ but fail to recognize him (see fig. 7). The composition invites viewers to visually traverse the path toward the distant monastery, much as they might envision the legendary journey of the Aymon brothers. The brothers’ forest refuge obscured their identity while distancing them from the clarifying context of civilization, the same condition in which the disciples find themselves before recognizing Christ. For premodern travelers, invocations of the Ardennes here might recall personal experiences of disorientation, where political and religious conflict could imperil and delay journeys.

This category pairs especially well with established interpretations of Patinir’s landscapes as spaces of spiritual pilgrimage, where the Christian charts a path through the wilderness toward condemnation or redemption. The natural contrasts that Reindert Falkenburg observed in Patinir’s works gain real immediacy if we treat them as visualizations of the environmental imaginary of the Meuse Valley. While the landmarks commemorating the hardships of the Aymon brothers were fixed, the climate surrounding them was not; storms and squalls rehearsed the conditions of the brothers’ exile for unlucky travelers. The journeys in these paintings were not merely allegorical but rooted in lived experience.

We might put this interplay between allegory and experience into practice in Patinir’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt (fig. 28). The Holy Family rests in the foreground, overlooking a vast landscape where a rounded stone monastery, often associated with Jerusalem, sits among rolling hills. Pre-Christian idols topple from the structure, and a pedestal is all that remains of one above a spring behind the Virgin. Viewers might animate the Holy Family’s escape and exile through references to the Ardennes, recognizing Montessor in the small stone structure embedded in the cliffs, or the Meuse in the winding river and jagged crags of the background. These landmarks simultaneously evoke real journeys through the Meuse Valley and the legendary evasions of the Aymon brothers. Further, the rounded temple and fallen idols could have reminded some viewers of Renaut’s final journey to Jerusalem in the Four Sons, or called forth the Ardennes’ pre-Christian past, particularly the etymological ties between Dinant and Diana, as noted by Guicciardini and Calvete de Estrella.

Such interpretations were readily available to early modern viewers familiar with humanist commentaries on the Ardennes’ mythic past. Dinant was associated with pagan divinities as early as the twelfth century, when monastic chroniclers saw in ancient spellings of Dinant (Deonant, Deonam, Dionant) a contraction of Deo-nam, presumably a pagan idol named Nant or Nam.94 By the sixteenth century, the etymology shifted: the Latin Dionantum was interpreted as an elision of Dianae and antrum, the grotto of the goddess.95 Speculative etymologies testify to a resurgent interest in Netherlandish antiquity in the sixteenth century. They also speak to a persistent impression of the Ardennes as a space haunted by the remnants of a pagan past. If the Ardennes was a setting for Christian conquests, it was due in part to its character as a realm of lawlessness and supernatural upheaval.

The final category, inversion and disorder, presents the Ardennes as a site of moral ambiguity where travelers were vulnerable to trickery. Bles’s The Parable of the Good Samaritan and Landscape with a Peddler Robbed by Apes play on this theme to different ends. In The Parable of the Good Samaritan, the twisting trunk of an aged tree rises from the left side of the picture; its dark leaves cast their shadow over the figures who have forsaken the robbed victim (see fig. 5). Patches of woodland surround the formidable crags in the background. Two paths are available to the beholder: on the left, the priest and Levite follow a road that winds through the split trunk of the tallest tree and snakes into the forest, continuing up the crag through a series of wooden chéraux––a difficult ascent for the sinful passersby. On the right, a straight, open road offers easy descent into a hamlet with houses and a church. The Good Samaritan, bearing the wounded traveler, takes the latter path, modeling a course of clarity and compassion. The river that flows between the two paths reappears in the distant background, echoing the Meuse as it disappears behind steep cliffs. To the premodern viewer, such striking rock formations and wooden pathways animated the parable in a physical landscape that conjured the moral quandaries of the Four Sons. The Aymon brothers’ defiance of Charlemagne, which could exemplify either noble resistance or rebellious insubordination, invited reflection on the relativity of duty and the consequences of moral inaction presented in the parable.

The moral instability of the forest takes on a different yet equally unsettling dimension in Bles’s Landscape with a Peddler Robbed by Apes, where deception and disorder reign in a wilderness that denies travelers agency and upends social hierarchies (see fig. 8). Leafy trees frame either side of the foreground, and the forest stretches from the riverbanks to the distant mountains. In this secluded setting, a band of monkeys ransacks the wares of a sleeping traveler. With gleeful abandon they drape his beads over high branches, pull trinkets from his clothes, and dance around the clearing. Their behavior, amusing to us but distressing to the hapless victim, recalls the subversive, untamed energy of Bayard, another animal antihero whose associations border on the dark side of the supernatural realm. Michel Weemans has traced the long iconographic tradition of the traveling merchant as a cautionary figure, whose extravagance serves as a moral lesson against overindulgence and sloth.96 We might build on this reading by observing how Bayard and the brothers make something of a fool of Charlemagne by constantly evading his grasp. The wilderness is not just a backdrop for the peddler’s––or Charlemagne’s––folly, but it actively fosters misfortune, bringing about a chaotic inversion of human order. Unlike The Parable of the Good Samaritan, where a clear moral path emerges, Landscape with a Peddler Robbed by Apes offers no redemption, only an unnerving reminder of nature’s capacity for deceit.

As sites of refuge, stages for exile, or domains of disorder, the landscapes of Patinir and Bles encouraged viewers to negotiate interrelated layers of meaning, much like they might navigate the wilderness itself. More than a simple tale of adventure, the Four Sons invoked political clashes, ancient histories, and ethical predicaments. The painter who invited associations with the setting of their trials enhanced the interpretive possibilities of the landscape, ranging from devotional meditations and historical reflections to cautionary tales. These are the kinds of ambiguities that appealed to viewers; the landscapes of Patinir and Bles might avail themselves equally to playful repartee or serious contemplation.

The incorporation of regional landmarks further exposes a practical reality of the painters’ surroundings: while they presented the Ardennes as a historic, mythic space, they also reflected a region in the first throes of industrial transformation. Over the course of the sixteenth century, metallurgy and charcoal production became increasingly organized endeavors, particularly in the riverside cities of Liège, Huy, Namur, and Dinant-Bouvignes. Patrons who purchased these paintings, such as Rem, and who passed regularly passed through the region, were themselves involved in ventures that contributed to these changes. The environmental imagination transcribed by Patinir and Bles may reflect a relationship to the land already in the process of historicization.

Patinir and his successor introduced stylized natural landmarks into their landscapes, but they were not the last masters to deploy them. At first the presence of these themes must have captivated viewers’ attention by engaging them in a cognitive exercise comparable to parsing an original literary metaphor.97 The beholder weighed multiple meanings to discern underlying connections that made the metaphor intelligible. Over time, however, the motifs evolved into widely known conventions, as elongated crags, hilltop fortresses, and wooden walkways proliferated across Netherlandish landscapes. As their geographic specificity diminished, so too did their cognitive demands on the beholder. When these elements entered the visual lexicon of masters who imitated and adapted Patinir’s style, they required less active interpretation, eventually functioning as idiomatic signifiers of wilderness. Their precise meanings faded, but the geomythic origins of these motifs were embedded in the very foundations of the landscape genre. This persistence raises broader questions: To what extent did viewers continue to recognize legendary topographies in the visual rhetoric of Northern European art? And what other overlooked allusions might be made visible through a geomythical framework?

Geomythology’s Value

As a method, geomythology resolves the persistent tension between literal and allegorical readings of the Netherlandish Weltlandschaft by incorporating each discipline engaged by the study of landscape. It is as attentive to environmental history and local, material knowledge of nature as it is to immaterial and ephemeral traditions once embedded in the terrain. Once this aspect of the premodern experience is recovered, it is difficult to conceive of a contemporary approach to these paintings divorced from those same circumstances. Beholders played an active role in constructing meaning, drawing from their lived familiarity with the Ardennes as well as lore such as the Four Sons.

Attending to geomyths in the landscapes of Patinir and Bles prompts renewed appreciation for their ambitions: the painters effectively expanded the expressive possibilities of their medium by invoking an embodied sense of place. Through firsthand experience, literary tradition, or legendary association, viewers encountered these pictures as animated geographies. As an art historical approach, geomythology has broader applications; it holds potential for reevaluating other aspects of Netherlandish painting, particularly adjacent genres like urban scenes and maritime subjects. Moreover, geomythology could be adapted to other eras and regions in art history that, like the premodern Netherlands, have storytelling traditions and belief systems that resist modern categories of definition. Here, it demonstrates what we stand to recover if we revisit these paintings with an eye to the environmental and cultural circumstances surrounding their production. The paintings of Patinir and Bles preserve a historical relationship to the natural world long overlooked by the conceits of modern art history. The recovery of this relationship not only expands the interpretive possibilities of these two sixteenth-century contemporaries but may well reinstate some mystery into our own environmental imaginary.