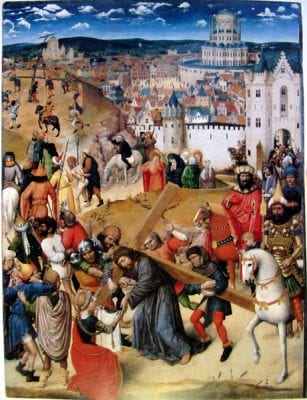

A fifteenth-century Christ Bearing the Cross has been attributed to the Utrecht painter known as the Master of Evert Zoudenbalch. However, scholars have noted details that link the panel to the city of Bruges and its Procession of the Holy Blood. This essay provides new evidence in support of these Bruges connections and links the painting to Passion plays staged in Bruges’s Procession. Known as the “City of Jerusalem,” and seen alongside the relic of the Holy Blood, these plays would have served as a focus for devotions, helping explain why an Utrecht painter might make such allusions to Bruges.

An early Netherlandish Christ Bearing the Cross from around 1470 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art) depicts Christ, front and center, stumbling as he makes his way toward Calvary (fig. 1). He is surrounded by a greater parade, which includes two other thieves, military officials, the many who mock and abuse him, and, of course, the faithful, most obviously Saint Veronica, who kneels ready to receive the imprint of the holy face, and the Virgin Mary with Saint John and other holy women. This noisy crowd spills forth from the gates of a prominent walled city in the right middle distance and circles round toward the mount of Calvary in the left background, where others prepare and raise the three crosses. The city looks quite similar to any contemporary Netherlandish city, with overhanging timbered houses and step-gabled facades, but for one obvious detail: in its center is a massive and archaic round temple, enclosed by a circular wall, with a ground level encrusted by half-round chapels, and its upper reaches narrowing to a low dome, supported by flying buttresses. Certainly intended to be Herod’s third Temple of Solomon, though loosely and anachronistically based upon the Dome of the Rock (albeit updated with Gothic flying buttresses), this structure helps transform an otherwise anonymous Netherlandish city into Jerusalem itself, an appropriate setting for the Way to Calvary.1

Based on the figural style of Christ Bearing the Cross, the Metropolitan Museum of Art supports the attribution of the work to the circle of an Utrecht illuminator, the so-called Master of Evert Zoudenbalch.2 However, in the museum’s fine catalogue of the 1998 exhibition of its early Netherlandish paintings, Maryan Ainsworth suggests a number of small but important iconographic details that might link this panel to the city of Bruges.3 This essay will pick up where earlier discussions have left off, providing new evidence in support of some prior conclusions and analyzing further the connections between this painting and cultural practices in Bruges, in particular the annual Procession of the Holy Blood, which itself included a fantastic cityscape of Jerusalem as a setting for a sequence of Passion dramas.

The current attribution of the panel to the Master of Evert van Zoudenbalch rests on stylistic and iconographic similarities to works by that master and his circle, who were most likely active in Utrecht.4 At the same time, Ainsworth notes that Christ Bearing the Cross, like other Zoudenbalch Master works, recalls paintings, drawings, and manuscripts from the circle and followers of Jan van Eyck. For example, figures along the left frame of the New York panel, in particular the two horsemen wearing violet and pink who ride away from the viewer, reappear in an Eyckian drawing in Vienna, which has transposed one horseman’s pointy hat to a pedestrian nearby (fig. 2). Many more figures from the right of the panel repeat in another Eyckian drawing from Braunschweig, including the group around the figure in the pink gown with fur lining–in particular his horse, the figure behind the animal’s muzzle and the youth clutching at its reins (fig. 3). The cuirassed centurion and the group around him also reappear in this drawing, including the frontal face to his left, and the man in profile behind, wearing a purple chaperon, whom some have tried to identify as the panel’s original owner.5 The New York panel conforms most closely to a later variant in Budapest, dated to circa 1530 (fig. 4), and to a much later (seventeenth-century?) copy of that work in the chateau at Gaasbeek, Belgium. Many of these same figures reappear in the Budapest panel, as do the tormentor behind the cross, raising his arm as if to strike, and the mocking figure in the left foreground, pulling at his ear. The Budapest panel also shares details with the Braunschweig drawing that are missing from the New York panel, in particular the second mounted authority figure on the right, other figures from that throng, including the two conversing figures in the background, and the two figures approaching from the lower right corner, which are also found in the Vienna drawing. Diane Scillia has further noted the similarity of details in the Metropolitan Museum’s panel to an early Crucifixion by Gerard David (fig. 5), where the same temple appears as a more distant backdrop, and where the two horsemen from the left frame also reappear as tiny details behind the cross, wearing similar costumes.6

Those same horsemen can also be found on the right side of the Way to Calvary that once appeared as folio 31 recto in the lost half of the Turin-Milan Hours (fig. 6). This folio has been attributed to the often-disparaged artist known as Hand K, who was part of the larger, less closely associated circle of Jan van Eyck working in Bruges in the 1440s or 1450s, and whose works are now associated with the Master of the Llangattock Hours7 The New York panel shares similarities with still other miniatures from the Turin-Milan Hours, most notably that massive and distinctive temple. A building with a very similar structure also appears in the background of the Arrest of Christ, folio 24 recto from the destroyed portion of the manuscript, attributed to Hand G (fig. 7), which some believe was Jan van Eyck himself8 Like the temple in the New York Christ Bearing the Cross, it also narrows from ambulatory to central nave and is crowned by a low dome supported by flying buttresses.

The Turin-Milan Hours eventually came to reside in Bruges sometime in the 1440s-50s, and the temple from the Arrest of Christ, or a variant of it, reappears often in images by artists in Bruges, in particular in manuscript illuminations, such as the buttressed temple in the Arrest of Christ from the Hours of Anne of Bretagne, from around 14609 As noted by Ainsworth, however, a similar structure also appears in Utrecht-school works, and in particular in works by the Master of Evert van Zoudenbalch, such as in two illuminations from the Van Amerongen-Van Vronensteyn Hours, also from circa 1460.10 This second manuscript suggests that other painted versions of this cityscape provide no particular proof for the genesis of the Metropolitan Museum’s Christ Bearing the Cross. Such iconographic motifs traveled freely from center to center, aided by drawings, such as those now in Vienna and Braunschweig, and by the movements of artists between different centers. Indeed Maurits Smeyers and Bert Cardon have discussed the numerous artistic connections between Utrecht and Bruges in the fifteenth century, noting that it was quite common to find Eyckian and/or Bruges-oriented motifs in Utrecht compositions.11

Other details in the New York panel, however, link it far more closely to Bruges and its traditions. Following Susan Urbach, Ainsworth noted a semi-legible vernacular inscription woven into the pink tunic worn by the horseman along the left frame, appearing on each hem of the draped sleeves and around the shoulders (fig. 8)12 Clearly visible in the inscription along the right hem of the right sleeve is the word bloet (blood), while the shoulder of the left sleeve reads omagame, a variant of the word for procession, ommegang, which Ainsworth rightly linked to Bruges’s renowned Procession of the Holy Blood.13 Furthermore, the cuirassed centurion along the right frame carries a gilded staff surmounted by a bird (fig. 9), which Ainsworth suggests “perhaps represents one of the many processional reliquaries made to house the Holy Blood.”14

That relic was under the care of the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, an elite group of twenty-six members, expanded to thirty-one in 1471, which was founded–or at least formally reorganized–in 1405, the first year the confraternity appears in official civic documents.15 Comparison of the figure of the centurion with an image in the sixteenth-century Parure Boeck, a book of the confraternity’s ornaments kept in its archives, confirms that the design of the pelican on the staff coincides to some degree with the organization’s coat of arms, as seen in a pattern for carved wooden decorations on torches carried in the procession by members of the Confraternity of the Holy Blood (fig. 10).16 Unpublished documents also confirm that the group indeed owned “a staff with a pelican,” having paid a goldsmith to make a new version of it in 1517.17 Other documents refer to “ons roedragher” (our staff-bearer). This was the clerk of the confraternity; he was a salaried assistant, named in many of the confraternity’s payments but never listed among its members. In some documents he is said to be “from Saint Basil,” the home of the relic, and he carried the staff during masses performed there for departed members;18 he presumably carried it in the Holy Blood procession as well.

The roedragher in Christ Bearing the Cross has an inscription on his armor, which Ainsworth called “indecipherable” (fig. 11).19 It can, however, be partly transcribed; its series of upper and perhaps lowercase letters reading:

[II] V I D [or n] A G A S P [r or I’] D E II [or N] C [or E] C [or E] L [ ]

But Ainsworth is correct: while partly legible, this inscription seems to make little or no sense in Latin or Flemish. And though the middle section might be understood to read “Gasp[a]r Den Cel – -,” no one with a name similar to that was associated with the Confraternity of the Holy Blood in later fifteenth-century Bruges.20

Behind the roedragher, and closer to the city gate, another armored horseman, part of a group of armed figures, carries a crossbow (fig. 12). He wears a red chaperon on his head and a brown woolen cloak; on the latter, over his right shoulder, is a white design with green highlights. While difficult to decipher exactly, some of the white embroidery suggests birds’ wings, or perhaps leafy branches. Either design would bring this garment close to the tabard worn by the provost of the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, which was also embroidered over the right shoulder, as illustrated in the confraternity’s Parure Boeck (fig. 13).21 Furthermore, the account books of the confraternity allot payments for the red hood to be worn by each year’s provost.22

While a new red hood was worn each year, the design of the robe would change, with each new provost wearing a tabard with a different combination of colored fabric and embroidery patterns.23 Unfortunately, the embroidery on the robe of the little man by the gate does not reflect any particular provost’s robe from the fifteenth century. A brown tabard like his was first worn only in 1480, while the way the figure’s robe opens below the collar, showing only the embroidery on his right shoulder, suggests a diagonal embroidery. Some tabards, but never a brown one, did sport a diagonal embroidery.24 It seems, therefore, that the panel’s robe is not a “portrait” of a unique costume but rather an amalgam of designs that might be seen in the Procession of the Holy Blood.

For the attentive fifteenth-century viewer, a Passion scene with these allusions to Bruges’s procession would also have recalled an important aspect of that annual celebration, namely the biblical dramas that accompanied the display of the relic on the city streets. The annual Procession of the Holy Blood can be traced back to at least 1256, but it only came to be dramatized in the late fourteenth century, with the first costumed actors appearing in 1396.25 Evidence confirms that a scene of Christ Bearing the Cross appeared among the plays that came to be staged in Bruges in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Joos de Damhouder described the entire Holy Blood procession in the mid-sixteenth century and listed the “plays of olden times,” still being enacted. There he recorded a fourteen-scene Passion sequence, including “the image of Christ, carrying the cross to the Mount of Calvary, followed by a crowd of Jews, women, and so forth. From the Evangelist Luke, in chapter 23.”26

Damhouder’s “plays of olden times” were recorded in Bruges’s municipal accounts throughout the fifteenth century. Individual subjects were sometimes named in the documents, but after the mid-1440s the municipal registrar listed all the plays under a single rubric, as “The Hovekin and the other plays,” or more often as simply “the Hovekin.”27 This Hovekin, the diminutive of hof (garden), was an enactment of Christ’s Agony in the Garden, usually staged in the Low Countries as a sequence that included the Arrest of Christ.28 There is no doubt that Bruges’s documents after 1445, listing only the Hovekin, indicated more than the words specify: in 1478, for example, the city itemized funds for only the Hovekin, yet an eyewitness writing in the Excellente Cronike van Vlaenderen recorded having seen “the Hovekin, the Last Supper, and many other pieces from the Passion of our Lord.”29 Similarly, in 1479 the municipal accounts again specified only the Hovekin, whereas the same chronicle writer described seeing “the Tree of Jesse, and the Last Supper, and the Hovekin, the capture, the scourging, and Annas, Caiaphas, Herod, and others very ornamentally made with paintings.”30 These Passion scenes were probably part of a dramatic sequence recorded elsewhere in Bruges’s civic documents as the “stede van Jherusalem” (city of Jerusalem). This production first entered the Procession of the Holy Blood in 1399, and continued to be recorded annually until 1434.31 It then became one of the many plays funded by the city under the rubric of the Hovekin during the second half of the fifteenth century. The best known document citing Bruges’s “City of Jerusalem” came in 1463, when the city paid the painters Petrus Christus and Pieter Nachtegale to renovate the massive production. This payment gives initial insights into the appearance of Bruges’s annual production, detailing the need for wood, iron, and canvas, the labor of a carpenter, and allotting money “for the food costs for LXXXIJ [72] persons, all busy on the day of the procession.”32 This huge payment, 40 pounds 8 schillings groten, was around five times what was normally being allocated for all the processional plays combined. And while the item does not separate the cost of materials versus those for labor, the total sum equaled more than three years’ salary for many master craftsmen.33 This spectacular construction, with scores of people required to operate and enact its dramas, suggests a multiscenic panorama of Jerusalem, probably not unlike the scene painted around 1470 by Hans Memling (fig. 14).34

Documents from the East Flemish city of Aalst provide further clues as to how that production might have looked. In 1432 Aalst sent representatives to Bruges for the canvas needed to make its own version of the “City of Jerusalem,” and that city’s more detailed description provides some idea of the scope and scale of the Bruges version that probably inspired it. Aalst paid for 150 yards of canvas; five oak trees for the wagon and support structures; twenty-two three-meter pieces of wood for the buildings; forty oak slats for curtain rings; hinged doors that opened at four joints; and “two sheets of white tin, from which were cut ëmen’ to stand up on the towers of the City of Jerusalem”; towers which were capped by eight decorative flourishes. Miraculously, the structure rested on four iron-plated wheels and was pulled through the streets with the assistance of at least nine people. The Aalst document also specifies that one of the scenes which appeared in its “City of Jerusalem” was a Last Supper, suggesting that both its version and Bruges’s indeed included Passion scenes.35

The “City of Jerusalem” listed in the Bruges municipal documents, then, seems to have been the suite of Passion scenes recorded by the witness to the 1478 and 1479 Holy Blood processions, and indeed his description of characters “very ornamentally made with paintings,” recalls the painted tin men in Aalst’s “City of Jerusalem.” Bruges’s municipal accounts confirm the continued performance of a Passion sequence in the Procession of the Holy Blood, paying for “the Hovekin and a suite of the Passion of our Lord” in 1508,36 for “certain performances from the Passion of our beloved Lord” in 1510,37 “various personages concerning the Passion of our Lord and other subjects” in 1511,”38 and “the Passion of our Lord, and many more [plays]” in 1512.”39 These are the legacy of the fifteenth-century “City of Jerusalem” and most certainly became the plays listed in Damhouder’s account of the “various representations of the Passion of Christ.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Christ Bearing the Cross, with its prominent Jerusalem cityscape and details evoking the Holy Blood procession, seems intended to recall this production. Like the Way to Calvary that comprised the Passion sequence described by Damhouder, the scene depicted in the Metropolitan Museum’s panel also seems to have come from Luke 23: Luke describes Simon of Cyrene, designated to help carry the cross, and the women of Jerusalem, whom Christ instructed to “weep not for me, but for yourselves and for your children.” Christ in the panel is indeed “followed by a crowd of Jews, women, and so forth,” including figures in the lower left corner corresponding to those weeping women.

The Eyckian elements of the Metropolitan Museum’s panel might further have functioned, in this case at least, as a reference to the plays that adorned Bruges’s Procession of the Holy Blood. A full examination of Bruges’s municipal archives has revealed the extensive role played by its painters in producing the annual Holy Blood plays. By the time Christ Bearing the Cross was painted, the principal responsibility for Bruges’s Holy Blood dramas had fallen entirely to its painters’ guild, and this group directed and supervised all other craftsmen working on the plays. Indeed, the city of Bruges paid only the painters’ guild, and no other group, for the Holy Blood dramas between 1445 and the early sixteenth century, and even after that the painters remained the principal caretakers of the annual dramatizations. The painters had begun by producing a single play in the entire sequence, the Hovekin, first introduced in 1397;40 when the city isolated its payments for the processional plays to the painters’ guild, the Hovekin became the rubric under which all other dramas were named, testament to how much the city had come to entrust its painters with the entire suite of Holy Blood plays.41 Christ Bearing the Cross seems to conform with a scene that appeared in the suite of dramas that rolled through Bruges each year as the “City of Jerusalem,” and the history of Bruges’s plays, especially the primary role played by its painters in producing those dramas, indicates why artists might have been susceptible to its motifs.

Social customs and practices in Bruges may shed further light on the other inscriptions from the figure in the pink tunic. Because of the natural folds of the drapery, certain words remain legible while others do not. Furthermore the mélange of upper and lowercase letters has led to earlier mistaken transcriptions.42 On the figure’s right sleeve the phrase, DAER SAT hI BLOET, translates as “there he sat [bleeding or naked],” while a word on the opposite hem of that sleeve, BELOV, seems to be a fragment of beloven, (a solemn promise or vow or a belief or trust).43 There is too little of the word before BELOV to hazard a guess as to its meaning; it appears to read NNEN or H HEN.

The right shoulder contains a word fragment, GHE [or C] OR [or P or n] PM, which I have not yet been able to translate, while the left shoulder bears the word OMAGAME, for procession. The left sleeve’s right hem contains another phrase, AL hAT EEN SCA, which seems certainly to read “already has a treasure” (scat), while the last words, BEEf GHELOVTE, come from beven (trembling in reverence of God) and gheloven (trust or belief in God’s word).44

These syntactical snippets begin to make fuller sense within the context of the panel’s iconography, which illustrates different events on the Way to Calvary. I have already noted Simon of Cyrene and the weeping daughters of Jerusalem from Luke 23, as well as Saint Veronica receiving the icon of the holy face. By tradition Simon and Veronica met Christ inside the walls of Jerusalem, behind the so-called Judicial Gate that appears on the right of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s panel. There Christ also met his mother, who then took a separate route to Calvary; she also appears outside the gates in the panel, behind a hillock with Saint John and four other women.

According to pilgrimage guidebooks, Christ fell under the weight of the cross, just as he does in the New York panel, on seven different occasions: when he first took up the cross; again when he met the Virgin inside the city gate, before she took her separate path; again with Simon of Cyrene; twice when he encountered Saint Veronica; a sixth time when he met the weeping women of Jerusalem; and finally at the foot of Calvary, looking up to where the crosses would be erected. Christ Bearing the Cross includes details that refer to each of these events in the crowd that surrounds Christ. Indeed the figure in the pink tunic seems to occupy the spot where that last fall would take place, while the inscription on his hem, DAER SAT hI BLOET, points still further forward, to the top of the mount, where, according to pilgrimage guidebooks, Christ would sit, naked and bleeding, while his cross was being prepared.45 These guidebooks listed indulgences available at each site, as well as the prayers that must be said in order to receive them.46 Most locations on the Way to Calvary promised an indulgence of seven years and seven forty-day periods, called carenen, while sites atop Golgotha offered a full plenary indulgence.47

Many Bruges citizens had made the pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the fifteenth century, most famously Anselm and Jan Adornes, who went to Jerusalem in 1470-71, following the example of others from their family, and used the experience to found the family’s Jeruzalemkapel, based on the design of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. This church became a focus for the city’s Jerusalem pilgrims, even before the founding of its Jerusalem Brotherhood in 1517.48 Others in Bruges and elsewhere in the Low Countries were encouraged to imagine a pilgrimage using special guidebooks developed specifically for that purpose. Each guidebook attempts to inspire a creative imagining of the events at the different holy sites and contains prayers for receiving the indulgences promised at each location.49

One such guide, written in the third quarter of the fifteenth century by an author in the guise of a priest called Heer Bethlem, recommends that readers imagine following Christ on the Way to Calvary, crawling on their own bloody knees and reciting a Pater Noster and an Ave Maria at every step. “If you want to go to Mount Calvary,” he writes, “you should ruminate devoutly in your heart on the disheveled Christ, covered with blood, as if you saw him before you, carrying the heavy beam of the cross.” Heer Bethlem later tells his pilgrim to imagine Christ sitting atop Calvary and to kneel and read five Pater Nosters and five Ave Marias, “in honor of his five bloody, glistening wounds,” in order to “participate in the all the indulgences and mercies that are given in this city.”50

Another early sixteenth-century guidebook by Jan Pascha has the mental pilgrim pray at the site of Simon of Cyrene that s/he too might be allowed to help carry the cross, in order to receive the indulgence.51 The guidebook published around 1500 by Hendrick Lettersnider in Antwerp breaks the Way to Calvary into thirteen points, most of which are alluded to by details in Christ Bearing the Cross. Lettersnider’s text lists the sites where Christ met the Virgin, Simon of Cyrene, Veronica, and the women of Jerusalem, the site where “Jesus, walking through the last portal of Jerusalem, was ridiculed and mocked,” and the place where Christ fell at the foot of Golgotha. This last site is the location for three of Lettersnider’s thirteen points: “Christ, seeing the place where the cross was to be, fell from exhaustion;” “Christ sat on a stone on that place called carcer Christi;” and “Christ was stripped, so that his wounds reopened.”52 This last site, where Christ sat on the stone naked and bleeding, is where the man in pink stands in the New York panel. Like these empathic prayers from mental pilgrimage guides, the inscriptions woven into the hems of his robe refer to Christ sitting and bleeding, to “solemn beliefs,” to storing up a treasure, and to “trembling in reverence” with “belief in God’s word.” Indeed, one inscription from the Metropolitan Museum’s panel seems especially close to a prayer written for the nuns in Maaseik, to be recited upon “ascending” Calvary, which reads “There he sat, beloved lord, depressed and breathlessly crying, while they prepared the cross,” and which gives the nun full forgiveness of all sins at the time of her death, and a guarantee of everlasting life.53

Unfortunately, none of these inscriptions directly quote any spiritual or temporal pilgrimage guidebook I have consulted thus far. However, I am not so sure that this is a problem; indeed it may have been intentional. I think that these inscriptions are best seen as semi-sensical, something I would like to call meaningful gibberish. The words are oriented in the same direction–all read vertically from the top–which not only facilitates reading but also implies that the words indeed have something to say. But the folds of the fabric deny, or at the very least complicate, specific identifications of many words and phrases. Rather than denying all comprehension, however, this skillful obfuscation instead allows the viewer to draw numerous connections to fifteenth-century texts and practices.

Returning to Bruges, its dramatized “City of Jerusalem” appeared in a context dominated by the relic of the Holy Blood, which had been delivered from Jerusalem during the Second Crusade in the mid-twelfth century.54 Like the sites visited by real and mental pilgrims, the viewing of this relic promised indulgences: Pope Innocent IV had granted the first in 1249 and 1254, followed by another from Pope Alexander IV in 1260. In 1310 Pope Clement V conferred a fourth indulgence, promising one hundred days to viewers of the relic on Fridays, plus five years and five carenen for viewers of the annual Procession, provided that they maintain a proper attitude of devotion. These would be followed by additional indulgences from Pope Clement VI in 1347, and from Bishop Ian of Armagh, the primate of Ireland, in 1472.55

With this relic and its indulgences, part of Jerusalem had indeed been transposed to Bruges. Pieter and Jacob Adornes, the father and uncle of Anselm, had also attempted such a transposition when they founded their Jeruzalemkapel in 1427. By then the city magistrate had already enhanced an association between the Holy Land and Bruges by introducing the annual drama of the “City of Jerusalem” into the procession, populated with events from indulgenced sites in the Holy Land. The plays appeared alongside the relic of the Holy Blood every year after 1399 and would have functioned very much like the illustrations in some mental pilgrims’ guidebooks, as inspirations for indulgenced imaginings. Mental pilgrimages were certainly practiced in Bruges: a text for a mental pilgrimage to Rome was presented to Margaret of York at her 1468 wedding in Bruges to Duke Charles the Bold, and a mental guide to Jerusalem, today in Stockholm, probably came from a Bruges workshop around 1510.56 The citizens of Bruges were even given papal permission in 1477 to use seven of their own churches as sites for an imagined pilgrimage, in lieu of the principal churches in Rome.57

Bruges’s relic from the Holy Land and the dramatized “City of Jerusalem” that accompanied it each year seem to have provided a locus for similar devotions, promising similar indulgences. The New York Christ Bearing the Cross seems to tap into that tradition, and its visual and verbal allusions to Bruges’s dramatized procession and to mental pilgrimages were probably intended to help its viewers transpose Jerusalem, and its indulgences, to their own city and to recall the prayers necessary for garnering those promised blessings.

In conclusion, I would like to return briefly to the genesis of Christ Bearing the Cross. If the panel is indeed by an Utrecht painter, either the Master of Evert Zoudenbalch or another artist from his circle, he seems to have been at least somewhat familiar with Bruges’s Procession of the Holy Blood, its plays and other trappings. It seems likely, then, that the painting would have been made for a patron with similar knowledge of that annual production. Unfortunately this does little to narrow the field of possible candidates for either painter or patron. It seems most likely that the original owner was either a Bruges citizen, someone who would have understood the votive nature of the “City of Jerusalem” and who would have responded to the details that evoked the Confraternity of the Holy Blood, or perhaps one of the many dignitaries who visited the city each year to witness the spectacular productions.

Many scholars have sought to recognize portraits in the figures in the cortège along the right edge of the composition, suggesting that they might be members of the Confraternity of the Holy Blood. Given what appears to be a provost’s costume, as well as the roedragher leading that group, this does remain a distinct possibility. However, comparing the painting with what is known about the costumes and customs of the confraternity, it seems less likely that this was intended as a group portrait. Indeed the level of specificity that members of the confraternity might have required seems to be lacking from this painting, whether it be a particular provost’s tabard, or an identifying inscription on the roedragher‘s cuirass. Rather I think these details were intended to function like the semi-legible inscriptions on the figure in pink, that is, to evoke rather than to specify, to guide the viewer toward a particular devotional context inspired by the Procession of the Holy Blood.

This panel’s owner must have been familiar with Bruges’s procession, whether as citizen or visitor. With this in mind, it is worth mentioning that after 1460 the Passion plays only appeared intermittently in the procession, which continued to be mounted every year. Plays were performed only ten times between 1460 and 1486, after which came a hiatus of over twenty years, certainly owing to fallout from Bruges’s rebellion against Maximilian, while the undramatized procession continued each year. Most of these later performances coincided with a joyous entry of the ruler in the spring, whether Philip the Good in 1463 and 1467, or Charles the Bold in 1468 and 1472, or Princess Mary of Burgundy in the company of Maximilian in 1478 and 1479, or Prince Philip the Fair in 1484, or Maximilian again in 1486. This means that during the 1460s-1480s a painting like Christ Bearing the Cross would have been as attractive for a guest as it would have been for a local. In 1468, for example, the annual procession fell between Charles the Bold’s first entry as duke of Burgundy on April 9 and his wedding on July 3; it also came just two days before Charles opened his first Order of the Golden Fleece, which brought a great number of foreign dignitaries to the city. Charles also entertained the ambassador of Calabria on the day of the procession, along with others from England, Normandy, Brittany, and Rome, and was joined by another ambassador from Aragon on May 6. Numerous foreign dignitaries accompanied Charles to the procession of 1472: ambassadors from France, Guyenne, Brittany, England, Naples, and Venice were in Bruges on May 1 and were joined by the ambassador of Cologne the next day. This listing begins to give some idea of the range of possible patrons for the New York panel: any one of them might well have desired a commemoration of the Procession of the Holy Blood. Each would have recognized the allusions to the procession in Christ Bearing the Cross. Like the dramas seen in Bruges, the panel’s Passion imagery would have helped viewers transpose Jerusalem and its indulgences to the Low Countries, and recall the prayers necessary for garnering those promised blessings.