Specialists in the study of gender and sexuality in early modern northern art are clarifying—and resolving—problems of evidence and method to transform the field. This essay assesses contributions that bear on visual culture in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, primarily in the Netherlands, with attention to gender, intersectionality, queering, and trans theory. Of particular importance is the concept of “female agency,” which assesses the exercise and limits of women’s power under patriarchy. I break from convention by proposing a more flexible and inclusive model, termed “situational agency,” which allows for greater variety and change in human experience and for variability in gender and power. Importantly, it resolves problems of context and periodization that have limited our understanding of early modern northern art.

Gender and sexuality are so fundamental to Netherlandish art that it is easy to miss their impact. Let us take a familiar work, Descent from the Cross painted by Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464) (fig. 1). Most readers will know Otto von Simson’s famous discussion of the rhymed poses that the Virgin Mary and Christ strike in the painting.1 Von Simson argued that this entwinement established Mary’s “theological dignity as co-redemptrix,” by which her compassio “helped to achieve the work of salvation.”2 She remained of secondary importance to Christ, of course, in a hierarchical approach that aligns with the theology of salvation.

If, however, we approach this painting with the recognition that power is fundamentally gendered, we can begin to see ways in which Rogier’s work reveals this hierarchy in more complex ways, and with broader relevance, than Von Simson described. For example, Mary’s torso is framed by floral green brocade and her lower body by grass, visual effects of her collapse toward the turf (fig. 2). These choices on Rogier’s part, previously unrecognized for their importance, modify the traditional iconography of the enclosed garden of the Canticum canticorum (the biblical Song of Songs): “a garden enclosed, sister my bride/a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed” (4:12). Christian moralists interpreted these verses as references to Mary’s virginity, a premise that was readily accessible to the artist and to viewers of the altarpiece in the fifteenth century.3 Writers advanced Mary’s purity as an archetypal state for contemporaneous women—an aim that informed not only Rogier’s image but also many others, which in turn enforced gender norms. The theme of the enclosed garden thus was both sexualized, by defining Mary as virginal, and gendered, by advancing expectations for sexual restraint primarily for women through a figure defined as female in both textual and visual terms. Accentuating the importance of the Virgin’s exemplarity for women, however, did not exclude men from appreciating Mary as a model. Gender categories and responses were far from fixed, with some men finding value in Mary’s sexual exemplarity regardless of its gendered framework.4 This situation might defy the initial expectations of researchers unfamiliar with methodologies that have arisen from feminism and gender studies.

This brief analysis of Rogier’s Descent is but one example of how new work on gender and sexuality can revise our understanding of visual culture, even for works that seem intimately familiar. The present essay briefly takes stock of selected scholarship that bears on the study of early modern northern Europe between about 1400 and 1600. My aim is to assess where this work stands and where we might take it. Although the Low Countries are the primary focus, I have added selected material on adjacent regions to demonstrate analytical variety, even as many other excellent contributions could not be cited. Some readers will be well versed in the essay’s nomenclature and methods. For those who are not, I have unpacked key concepts and cited selected resources for consultation.5 Concepts for discussion include female agency, visuality, intersectionality, queering, and trans theory. These and other developments in the humanities are fueling an exciting wave of innovative and challenging art-historical scholarship.

The concept of female agency merits particular attention, for this longstanding, transformational approach to the study of cultural production is currently in flux for the early modern period. Traditionally, investigations of the kind have sought to understand the actions women took despite and against the limitations imposed on them by patriarchal forces, to demonstrate women’s ability to tangibly improve their situations.6 The concept therefore invites us to consider who held power in gendered terms as well as why, when, under what conditions, and to what extent. Scholars of the humanities have been asking and answering these questions about early modern women for decades, such that historian Merry Wiesner Hanks described female agency as a “venerable concept” in her 2021 anthology on the subject.7 Art historians have been instrumental in building this new knowledge. They continue to explore women’s contributions to production—the study of female artists is once again a priority—patronage, collecting and display, and reception. They also are building on earlier analyses of female agency as understood through depictions of women. Thanks to this continuing work, we now know much more about these topics than we did even a decade ago.

Over time, however, and responding to revelatory research that is complicating the field, I have come to find the standard premises of female agency too limiting for the historical period addressed here. This essay therefore offers a new and more flexible model that I term “situational agency,” which accounts for contextual differences, challenges of periodization, and interpretive variety. In its broadest sense, I define situational agency as a form of power exercised by or on behalf of ostensibly disadvantaged persons, regardless of demonstration of improvement to any person’s situation. This approach, presented in detail below, dovetails with other innovative methods, including those named above, that help us to recognize obscured populations and create more space for marginalized perspectives. It does not, however, elide women as a central subject of study, a concern raised recently by some specialists. Rather, situational agency makes common cause with other new methods by redressing the exclusionary scholarly narratives that inspired the earliest investigations of gender and sexuality in history.8

Gendered Artists and Artmaking

Our understanding of gender in early modern visual culture has deepened considerably since 1971, when Linda Nochlin rightly insisted that we confront the question “Why have there been no great women artists?”9 This query is omnipresent fifty years later in the spheres of research, teaching, and publicly minded cultural studies, where it finds reference in writings ranging from scholarship to syllabi to blogs. Certainly, Nochlin was right to conclude that it was an “erroneous intellectual substructure,” not a lesser capacity or capability, that had impeded the professionalization of historical female artists.10 By this she meant, simply stated, that biases embedded into society disadvantaged women. Today, writers might use terms like “systemic” or “structural” to describe these embedded biases. In practice, structural biases shaped early modern life experiences and opportunities, from the long-term and far-reaching to the everyday. Among the limiting effects of gender bias in visual culture was the exclusion of women from the apprenticeship system and most, later, from the formal instruction of European academies. Furthermore, regulations barred women from observing the nude human form, out of a concern that it would contribute to their moral laxity. Life drawing enabled artists to become skilled in rendering anatomy, a primary benchmark of the evaluation of ability in Western art through the nineteenth century. Exclusion from it thus not only blocked access to a key technique but also provided a circular argument for the inferiority of women artists: women could not study the nude form because of their presumed moral weakness and, having not studied that form, they produced work that was deemed inherently weak and, thus, unworthy of cultivation. It also led to little coverage for female artists in the rising body of literature on artists’ lives. Such was the case with Karel Van Mander (1548–1606), who discussed only a handful of women in the 1604 Schilder-boeck and then only within sections on male artists rather than in dedicated entries. For instance, the artist Margaret van Eyck made only a brief appearance within the section on her brothers, Jan and Hubert van Eyck.11

The problem is not simply historical, however; it is also disciplinary. Nochlin rightly argued that these conditions shaped the practice of art history, where a “white Western male viewpoint” continued to drive inquiry away from questions of social injustice. Against that backdrop, Nochlin’s invitation to question foundational disciplinary premises, along with others that have come in its wake, encouraged a new body of scholarship on women’s contributions to early modern visual culture, including investigations of agency among female artists. Now, five decades later, we know much more, not only about many of these artists but also about women as patrons, collectors, viewers, and subjects of pictorial representation.12

Yet many new ways of thinking about artists and gender have arisen in the interim, some quite recently. For example, only in 2019 were Mayken Verhulst (1518–1599), a successful miniaturist, and Volcxken Diericx (1525–1600) credited in detail for advancing their spouses’ posthumous reputations: Verhulst married the Brussels artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502–1550), and Diericx’s husband was Hieronymus Cock (1518–1570) of Aux Quatre Vents in Antwerp. A recent essay by Arthur J. DiFuria demonstrates that these two figures played central roles in advancing their husbands’ work in difficult market circumstances, an argument that sheds light on contributions to visual culture that previously had gone unrecognized.13 Indeed, DiFuria notes that the literature on Coecke van Aelst and Cock rarely identifies Diericx and Verhulst by name.14 The historical gendering of artistic quality has been instrumental in establishing the centrality of these and other male artists, whose professional reputations, accessible records pertaining to them, attributable works, and supposedly deeper intellect made them more highly valued as subjects of research. These perceived qualities also made them safer choices for aspiring scholars and, in turn, perpetuated the myth of male genius.

There are, of course, limits to how much we can push back against the historical factors that have obliviated women’s efforts. The invisible nature of the labor women performed in workshops, markets, and other sites of visual culture means that many of these figures will never be known to us. This is true despite the growing number of images of women’s labor produced throughout the sixteenth century, such as Spinning, Warping, and Weaving (fig. 3) by the Leiden painter Isaac Claesz. van Swanenburg (1537‒1614), analyzed by Susan Broomhall and Jennifer Spinks.15 One wonders if these images, made and commissioned largely by men, primarily offered views of women’s work that upheld male rather than female viewpoints. Likewise, new research will never reveal the full extent of women’s artistic production, regardless of qualitative judgment. The materials and forms more readily available to women (e.g., the fiber arts) are difficult to preserve and historically have been undervalued; some art historians use the term “makers” rather than “artists” in recognition that cultures did not value some material forms in which women worked as “art.”16 Even those objects that survive are often kept out of sight, and thus out of mind. The fragility of these works often precludes travel as loans to exhibitions and even their display as part of a museum’s permanent collection. These situations create inequities that elevate works by men over women in cultural institutions, as Andaleeb Banta of the Baltimore Museum of Art reiterated recently.17 Fortunately, progress is still possible, as in “Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800,” a new exhibition co-curated by Banta and Alexa Greist of the Art Gallery of Ontario.18

Even with the limitations noted above, it is clear that early modern women sometimes resisted restrictive gender ideologies (resistance is a form of agency in and of itself, as I argued long ago).19 Acts of resistance were most often subtle, but they could also be visible and publicly consequential. In some cases, these efforts and their outcomes were reflected in visual culture. Such was the case at the Augustinian Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis (Hospital of Our Lady) in Mechelen, best known today for its famous besloten hofjes (enclosed gardens) produced in the early decades of the sixteenth century: objects formed of handwork installed in upright cabinets, to which painted wings were usually attached. In the era of the hofjes, clerics charged with oversight of the hospital were attempting to tighten their control by levying accusations of negligence against the nuns, pertaining to conventual vows and care of the infirm. Reforms, they argued, would resolve these problems. Unwilling to relinquish their relative independence, the nuns rebuffed clerical intervention for over a decade. Their resistance ultimately failed, however, when Jacob de Croÿ (1478–1516), Bishop of Cambrai, forcibly imposed reforms in 1509. He assigned two sisters, Cornelia Andries (d. 1528) and Jozijne van Coolene (d. 1557), of the reformed Augustinian hospital of Saint John near Brussels, to the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis as “mother” and “first sister,” charging them to instruct the nuns and to ensure enforcement. A besloten hofje commissioned fifteen years later (fig. 4), probably by Cornelia and/or Jozijne in particular, commemorated the success of the reforms and, by extension, reinforced the failure of resistance. Portrait wings to either side of the central garden depict the reform’s leading figures, their roles conveyed by inscriptions. Cornelia appears on an interior wing opposite the rentmeester (financial administrator) assigned to the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis, Peeter van Steenwinckele (d. 1525), an Augustinian canon of Notre-Dame d’Hanswijk in Mechelen. Jozijne’s portrait is on the exterior, opposite one of Marten Avonts (d. 1533) of Hanswijk, Peeter’s successor as rentmeester (fig. 5). This work, completed in 1528, just after Peeter’s death, suggests that Marten, too, would contribute to sustaining the hospital’s ideals. Probably accessible to visitators and the public, and certainly so to the sisters of the hospital, the hofje asserted the durability of reforms in a community with a locally known history of resistance. Importantly, it also demonstrates that some early modern women did not tolerate acts of resistance by other women, such that women might work against each other’s efforts.20 Some scholars have considered such acts to collude with patriarchal hegemony, a point to which we will return.

Certainly, however, the pressures women placed against constraints were often subtly expressed, executed out of the public eye, or absent from the historical record. Such situations can plague researchers who seek evidence today, for correspondingly few direct archival sources documenting these activities by marginalized people are available. Yet reasonable conclusions can be reached. For example, young women excluded from the apprenticeship system could nonetheless negotiate access to materials and informal training, primarily in the workshops of male relatives (who in some cases may have initiated the idea or provided other sorts of encouragement). Instances of this practice correlate strongly with elevated wealth and social status, factors that excluded other women—and some men, too—from such pursuits. A successful painter who ostensibly studied in this way was Catharina van Hemessen of Antwerp (1525–after 1583), whose father, Jan Sanders van Hemessen (active by ca. 1524–ca. 1564), apparently trained her. It was not only access to apprenticeships that held women back, however. The unavailability of life drawing to Van Hemessen is reflected in anatomical peculiarities that to my eye characterize aspects of her figure in her Self-Portrait (fig. 6), understood to be the first representation of what quickly became a key iconographical type in early modernity and beyond: the painter at an easel, brushes and palette in hand, at work on a composition. However, it may have been that Van Hemessen and other female artists found ways to capitalize on the stylistic differences that resulted from these constraints, much as some specialists on fifteenth-century prints now accept that viewers considered the print media of the period (woodcut, engraving) to elicit distinct aesthetics that beholders appreciated on their own merits rather than hierarchically.21

Indeed, Van Hemessen’s self-portrait demonstrates significant intellectual and social ambition, shaped through a complex constellation of associations that complement the painting’s novel iconography. Among the possible points of reference is the painter Marcia, known to early modern intellectuals from Pliny’s Historia naturalis, who purportedly used a mirror to render her own features in portraiture.22 Van Hemessen omitted a mirror from her painting, however, which marks a telling departure from most images of Marcia. It therefore seems likely that she intended to give greater emphasis to a different strand of self-portraiture: the theme of Saint Luke painting or drawing the Virgin. Male artists such as Rogier van der Weyden had made powerful claims to divine inspiration through this iconography, in which they represented themselves in the guise of their patron saint, to whom legend had assigned the privilege of generating images of the divine.23 Of particular historical importance are images made or displayed in Antwerp, where Van Hemessen could have seen them, including a triptych from the workshop of Quentin Massys (1465/6–1530) (fig. 7). An image of Saint Luke on the right-hand wing is close enough to Van Hemessen’s self-portrait in general composition, figural pose, and representation of the tools of painting that it seems a likely source of inspiration.24 The motif of Saint Luke matters precisely because it had been a means for gendering the practice of painting. By appropriating that gendered motif, Van Hemessen grafted onto herself a set of intellectual significations and claims to divine inspiration that male artists traditionally had held as their own. Furthermore, Céline Talon has argued that Van Hemessen used her portrait to assert expertise with color theory and paint application. In so doing, she implied skill with miniature painting (a medium known at the time for its difficulty) as well as the ability to render flesh tones, which was becoming more highly valued.25 Both Talon and Jennifer Courts, in a separate essay, have each described the painting as an example of ingenium, the ability of an artist to invent. It therefore seems that Van Hemessen wished to claim a capacity for ingenium that rivaled her male contemporaries.26

Even as Van Hemessen’s self-portrait was carefully strategized for self-positioning and advancement, a cautionary note is in order. Jennifer Courts has proposed that Van Hemessen may have pursued painting not as a means by which to achieve professional success but rather to elevate her social and economic status.27 Courts framed the pursuit of panel painting as a strategy that eventually resulted in Van Hemessen’s appointment to the prestigious position of lady-in-waiting for the Netherlandish regent Mary of Hungary (1505–1558) at the court in Madrid, a position occupied by very few non-noble women and one in which Van Hemessen did not paint, at least not to our knowledge. Even so, the entanglement of gender and art is instructive. Van Hemessen’s professional trajectory demonstrates that women’s strategies, and the outcomes of their acts, might not align with the initial expectations of researchers. One might, for instance, pursue painting not for its own sake, but rather because this traditionally male-dominated practice could offer a woman rare opportunity to increase her visibility, demonstrate a cluster of valuable skills, and thereby create special kinds of social and economic mobility. This is but one example of the importance of questioning the enduring assumptions of art-historical gender studies.

Problems of Evidence and Method

Catharina van Hemessen (fig. 6a) is one of a few northern European woman artists working between 1400 and 1550 about whom we have substantial evidence, including a good selection of signed and/or reasonably attributable works. Yet, on the whole, much less is known about female artists of this period than of the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Works firmly ascribed to these women are, furthermore, few. In some cases, evidence of a female artist can be found in the archives, although no extant works can be inarguably attributed to her. Such conditions render these figures and their contributions to visual culture elusive and correspondingly difficult to analyze.28 They also explain the shortage of volumes covering this era in an otherwise robust book series called Illuminating Women Artists, published by Lund Humphries in partnership with Getty Publications, for which Italianist Marilyn Dunn and I are coeditors for the Renaissance and Baroque periods.29 The situation is different for the seventeenth century and beyond, when more female artists were documented and from whom a greater number of securely attributed works are known. A special issue of the Netherlands Yearbook for the History of Art on women artists and patrons, edited by Elizabeth Honig, Judith Noorman, and Thijs Weststeijn and expected in 2024, may bring additional women artists from the earlier period to the fore.

In answer to Nochlin’s observation that female artists are rarely the subjects of monographs such as those in Illuminating Women Artists, books in the series perform an important service by intervening in a format that appropriates the male-centric model of the solitary artist-genius inherent in these types of studies, which were typically dedicated to men. Yet specialists are also using other approaches for deepening our understanding of women artists, and they are ascribing different merits to these methods. Virginia Treanor has argued that grouping female artists for investigation holds value of a different and potentially more important sort than monographs about individuals, for such studies “dispel the myth of exceptionalism” that traditionally served patriarchal ends. This approach also takes its subjects on terms congruent with their historical circumstances: women artists were not singular, isolated figures in the economies of the visual arts, Treanor points out, but rather contributory and influential actors within them, even as they often produced individualized, self-referential images such as Van Hemessen’s self-portrait.30 Male artists were not singular in this way either, but the uneven application of a monographic approach has sustained a gendered hierarchy embedded in the patriarchal structures of history.

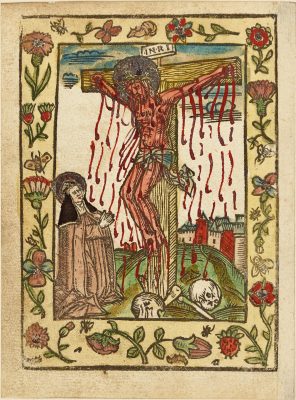

Grouping artists for study has other benefits, as well. It can inform us of social networks and collaborations among artists and their contemporaries, and it can reveal unanticipated continuity and variety across a range of topics, from technique and iconography to market dynamics and the circulation of objects. Certain south-Netherlandish nuns, for example, made and commissioned prints. These works arose from various and complex motives, and they were strategic in iconography as well as circulation. Ursula Weekes examines this historical richness, arguing that nuns sent prints they made or commissioned to other religious communities, where these objects may have fostered reciprocal kinship (fig. 8).31 Tracing the mobility of objects among women and their communities has thus helped to reveal women’s engagement with cultivating social networks as well as the advantages they found in doing so. Furthermore, these networks crossed boundaries that were themselves fluid: among families, between the sexes, and among lay and conventual communities. What we know of networking will grow with emerging technologies. The digital project “Global Makers: Women Artists in the Early Modern Courts,” by Tanja L. Jones and Doris Sung, is an example of the usefulness of visualization models in forming new knowledge.32

With limited historical evidence about certain issues of gender and sexuality at our disposal for the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, including women artists and works made by them, scholars are hard-pressed to understand or even identify historical examples. The situation lends a specific kind of difficulty to this type of study. Archival evidence on which one can rely to tackle certain types of questions, including account books, inventories, and wills, can help. So can textual evidence within images, such as the inscriptions in the besloten hofje from Mechelen (see figs. 4 and 5), which identify the people represented by the four portraits. Texts cannot, however, support inquiries of gender and sexuality in isolation from other evidence, including—perhaps especially—visual evidence. Such study therefore demands methodological flexibility, as well as the implementation of research practices that move past strict archival research to embrace informed hypotheses, an approach to the field that I have practiced for many years. This mode of analysis is analogous to the concept of “critical fabulation” advanced by historian Saidiya Hartman in answer to the archival omissions of the lives of the enslaved.33 As a form of scholarly empathy, this work constitutes its own special rigor in the identification and exploration of historical possibilities that certain practices of the past obfuscated, including the writing and preservation of records. Jennifer L. Morgan, a specialist in the history of the Atlantic slave trade, has challenged scholars to explore more deeply than they have before the factors that caused these omissions and erasures, which created a “pantheon of silence” that “produces damage across the board.”34 Indeed, limiting the evidence to archival or literary sources alone can obscure women’s activities by eliding other means we have at our disposal to understand them, a problem we will return to below, in regard to agency.

The Power and Problems of Binaries

A body of scholarship on northern art produced in the last decade maintains that it is not enough simply to recognize that the binary categories of “male” and “female” are cultural constructs with which societies govern the bodies of their constituents. Scholars are exploring the fault lines in the regulatory mechanisms that arise from those binaries, the moments in which the economic and political realities of lived experience render crisp distinctions suddenly porous or even untenable. It is likely that new studies will reveal more—perhaps many—instances of symbolic gender appropriation and fluidity of the sort we find in Van Hemessen’s self-portrait, with its references to Saint Luke. Years ago, I termed such acts “regendering,” the aspirational adaptation of a generally opposing yet advantageous gendered type or feature with the aim of advancing one’s status, situation, or power.35 An aim of that research was to consider how Joan Wallach Scott’s concept of gender as a “primary way of signifying relationships of power” between women and men, and Judith Butler’s premise of gender performativity, might help us to clarify and resolve latent problems in the study of early Netherlandish art.36 One focus of that work was the devotional portrait diptych, for which I argued that the few women known to have commissioned this male-dominated type did so either to gain ground or to align themselves with characteristics of masculinity for politicized advancement. One example is a diptych representing and presumably commissioned by the Netherlandish regent Margaret of Austria (1480–1530) (fig. 9), who sought to align herself with her Valois male forbears by appropriating an artistic format and visual language that were inextricable from ideals of courtly manhood and men’s political power.37

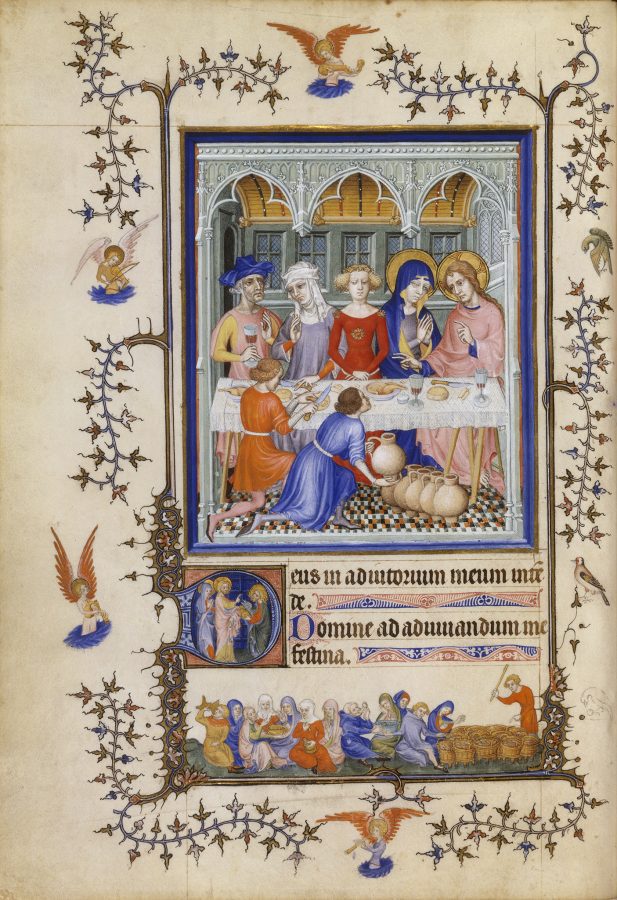

In the years since, writers have interrogated power relationships in contexts of inequity to complicate the gendered landscape. Consider, for instance, Diane Wolfthal’s invaluable demonstration that early fifteenth-century artists depicted male servants as effeminized to convey their lesser status in relation to the elite men whom they served.38 In the context of class, these effeminized men served other men and also women who were above their station. Such is the case in Wedding Feast at Cana (fig. 10) from the Très Belles Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry (d. 1416), where male servants kneel before a bride who stands over them in a position of privilege. This arrangement forms and reflects a hierarchy in which class distinction overrode gender difference: men of lesser station were subject to hierarchical subordination not only to men but also to women, even as women were subordinated to men of their own class. Wolfthal’s essay exemplifies the value of thinking through the visualized relationships of gender alongside other social constructs that artists endeavored to represent. It also points to variations in the pictorial repertoires developed to comment across categories (such as gender and class; gender and race; gender and sexuality; etc.), an area about which we need to know more. Similarly, in the sixteenth century, members of the German Marian confraternity of the Scuola dei Tedeschi in Venice who commissioned Albrecht Dürer (1471‒1528) to paint the Feast of the Rose Garlands (fig. 11) did so in a context of gender hierarchies that John R. Decker has helped us to understand. Decker notes that municipal authorities in the city limited the mobility and visibility of men in the German community through regulations similar to those by which they controlled Venetian women. The painting’s imagery countered this gendered Othering though a pictorial language of ideal Christian brotherly unity aimed to advance the group’s standing.39 One wonders, though, if this pro-German messaging by a German artist was successful in Venice: the portraits of the sparring leaders Pope Julius II and Emperor Maximilian that are included in the work portray the two as equally authoritative, a message Venetians might have rejected. We need to know more about the application of gender strategies across geographies. The studies by Wolfthal and Decker, one focused on the north and the other on Italy, suggest that certain approaches held transcultural appeal.

Also of considerable value are publications that explore the unstable nature of gender in relation to other types of identity. Sherry C. M. Lindquist has rightly observed that “ambiguities and reversals” in gender and sexuality mean that we must “juggle multiple binaries” that do not revolve exclusively around these issues (and may not even involve them at all).40 Lindquist’s essay opens a volume on gender and Otherness edited by Carlee A. Bradbury and Michelle Moseley-Christian, the essays of which demonstrate the complexity of the matter within specific historical contexts. For instance, Marian Bleeke argues that a transi (cadaver) tomb sculpture of Duchess Jeanne de Bourbon-Vendôme (1465–1521) (fig. 12), with its protruding entrails and allusions to pregnancy, negotiated the binaries of purity and procreation, life and death, even Other and self. The result communicates “the everyday monstrosity of motherhood” and the maternal experiences of Jeanne, including the death of her and her first husband’s son and heir.41 These binaries were consequential insofar as they marked moments of profound change in the human lifecycle. The first experience of childbirth thrusts a person into parenthood, demonstrating how quickly changes in status could happen, whether expected or not. Assessing such complexities is difficult, as Lindquist noted, for the resulting multiplicities and the ways they challenge our sense of the past raise seemingly unending interpretive possibilities for identity re-formation. I would add that specialists might tease apart these binaries further by approaching gender protocols as if they reside on malleable spectra, with intersecting gradations that can complicate our understanding of gender in visual and historical terms.

The great seals of Duchess Mary of Burgundy (1457–1482) are a case in point, for they illustrate intersections between visual culture and the playing out of gendered tensions between intention and reception during a moment of profound change, with immediate consequence.42 At the unexpected death of her father, Duke Charles the Bold, and her sudden elevation as lord of the Burgundian polity in 1477, Mary commissioned from metalsmith Jan van Lombeke a new seal-die for the authentication of legal documents. The resulting wax seals (fig. 13) depict her as a hunter, riding a steed and surrounded by dogs. The imagery resonated variously: with tropes of the hunt, including the seemingly conflicting states of purity and procreation described in medieval literature; with the ducal seals of Mary’s male political forbears, who appeared as mounted knights charging into battle; and with representations of female warriors such as the virgin Amazon queen Penthesilea, with whom Mary’s supporters compared her favorably. These associations may have advanced Mary’s claims to leadership among some viewers. Yet, at the same time, artists and writers were reshaping the personas of Penthesilea and other women like her to emphasize defeat rather than heroism. This situation likewise grafted qualities of political vulnerability onto Mary by association, which probably worked against her in rivalrous interpretive communities with exposure to this new version of Penthesilea’s narrative. One such community was the French court, where Louis XI (1423‒1483) had invoked Salic law in an attempt to annex the Burgundian territories, and where Penthesilea was notably disempowered in contemporaneous texts and images. This perspective on Mary’s seals illustrates the importance of considering not only how the duchess and her advisors wished to shape her persona at a critical moment but also how the reception of gender ideologies, and the reception of gendered images, impacted the complicated landscape of early modern cultural production.

Aspects of the publications addressed above were inspired ultimately by situational intersectionality, a form of analysis developed by the critical race and gender theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in the late 1980s. This work arose from the dissatisfaction of Black women with exclusionary structures inherent in white-space feminism,43 and the critical framework that emerged from it has been profoundly important for scholars throughout the humanities and social sciences. Intersectionality as currently practiced understands identity as culturally constructed, pluralistic, and in flux. Among the categories to which it attends are race, gender, class, disability, religion, and age, any and all of which can come to bear on a historical situation in various and seemingly unlimited combinations.44 Penny Howell Jolly’s study of the Othering of Black Africans and Jews by conventions of jewelry in Christian-themed Flemish paintings exemplifies this approach.45 Jolly demonstrates that earrings worn by the Black and Jewish figures in the Adoration of the Magi in the central panel of Rogier van der Weyden’s Columba Altarpiece reinforced the “power of being a Christian insider” by “heightening the otherness of the earringed outsider.”46 In pairing these two figures with the Adoration theme, Jolly continued, Rogier implied their imminent conversion to advance Christianity’s “universal appeal.”47 However, evidence for intersectionality in the Low Countries in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is often hard to find or subtle enough that we have yet to recognize it. To see those topics and practices requires new modes of attention, modes that arise from our willingness to read the work of people, like Crenshaw, who help make legible historical phenomena that other methods have been unequipped to detect. The strongest demonstrations of intersectionality in early modern art weave together perceptive observations and innovative ways of interpreting available evidence. We need more work that attends to history in this way.

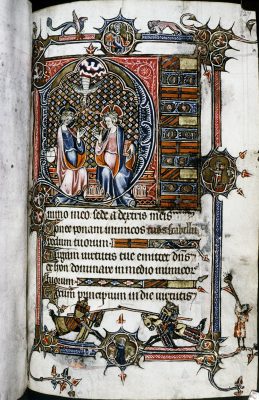

A new and promising way to understand the complexities of art in the early modern Low Countries is through the interdisciplinary lens of transgender theory, which likewise challenges binary constructions. Historians have recently begun developing this area of study, and things will continue to change quickly as the field evolves. Hagiography, for instance, is a rich evidentiary proving ground for theoretical application, as demonstrated in a 2021 anthology edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt.48 The volume challenges scholars to investigate the “full ideological existence” of transgenderism, which the editors define as “a rubric for discussing ways of being that disrupt normative notions of binary gender/sex.”49 Medievalists are ahead of early modernists in this area, in part because they have done more to explore gender fluidity in hagiography. A recent essay by art historian Maeve K. Doyle has extended the discussion to specific images in a secular context, an important scholarly move, as the depicted individuals analyzed were members of the laity rather than saints. In particular, Doyle defines conceptual spaces implied by manuscript owner portraits in late medieval France, portraits in which “gender identity and devotional performance are interconnected in intimate, non-linear, and inextricable ways, and their fabric is constantly in transition.”50 Those spaces, Doyle argues, exist outside traditional gender constructs; they are, therefore, “transgender,” and they invited “transgender reception” on the part of historical viewers. Illustrating this approach is a folio in a prayer book with representations of a married couple in the borders: husband Joffroy d’Aspremont dressed as a knight on the right and wife Isabelle de Kievraing kneeling in prayer at the bottom (fig. 14). Doyle contends that Joffroy could have seen himself in the representation of Isabelle in the course of devotional exercises involving the book and that Isabelle could have seen herself in a knightly role drawn out of the bas-de-page jousting scene, since medieval prayer books advanced the tournament for all potential readers and viewers as a metaphor for spiritual struggle. Doyle’s approach does not claim a transgender identity in the contemporary sense for any late medieval person associated with this book. Rather, it deploys the concept to release gender from the rigid binaries implied by the depiction of female and male bodies, a scholarly strategy that allows Doyle to account for variability and interpretive multivalences that we might otherwise fail to recognize, let alone comprehend.

Doyle’s application of transgender theory to issues of viewer experience and reception deepens our understanding of medieval and early modern art while avoiding ahistorical impositions of the present on the past, a practice that specialists are taking care to avoid. Consider, for instance, Robert Mills’s cautionary note in his analysis of the Triptych of Saint Wilgefortis (fig. 15) painted by Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450–1516), where a bearded female saint is crucified.51 Saint Wilgefortis therefore becomes Christlike in defining if limiting ways. Mills rightly observes that Wilgefortis’s sexual transformation was partial and temporary rather than complete and permanent, concluding that it is decidedly different from modern transgenderism. Still, as recent work like Doyle’s demonstrates, there is plenty of room to acknowledge the complexities of sex and gender in early modern visual culture, so long as we take care to recognize the important differences between early modern and contemporary ways of thinking about these matters. We need more work that provides historicized possibilities—multiplicities, multivalences, and spaces for transgression. The accent of these analyses on scholarly reconstruction may make some readers uncomfortable. Yet a fragmentary archive made misrepresentative by patriarchal practices requires attention to lacunae, and new ways of contending with them, if we are to avoid recreating its preferences and reinforcing its strategic omissions. These interventions perform two important functions. First, they shed light on people and practices that have long been overlooked. And second, they speak to new scholarly possibilities, new ways of seeing not only the objects that seem intimately familiar but unfamiliar ones as well.

Sexual Desire

Specialists are sharpening our understanding of visual evidence about sexuality in early modern northern art—which can be difficult to identify, as we will see—and they are experimenting with new methods as well. Some writers have explored the boundaries of sexual normativity and transgression in imagery to suggest how images could have been interpreted to uphold or challenge conventional practices—or both at the same time. Others are thinking about images as directly or indirectly accepting or even celebratory of sex, including same-sex interactions. Although sexuality and gender are addressed separately for the purposes of this essay, this choice arises from analytical necessity rather than from facts on the ground. The two issues often were entwined in the minds of early modern people, and both categories can be operative in a single work. With this in mind, I offer some thoughts on the study of sexuality as an isolated subject, noting that most of the images discussed also have something to tell us about gender.

Unsurprisingly, scholars have found that most early modern images pertaining to sexual desire affirmed the regulatory mechanisms of heteronormativity available at the time. Such was the case with Neptune and Amphitrite (fig. 16) commissioned by Philip of Burgundy (1464–1524) from Jan Gossart (ca. 1478–1532), even as the imagery challenges other contemporaneous norms. Stephanie Schrader has proposed that this painting invited the patron to identify with Neptune, presented as the quintessential sensualized male. Philip was fifty-one years old at this time, yet Gossart depicted Neptune youthfully, at the height of his virility.52 Certainly, this approach was intended to flatter Philip. However, as Schrader demonstrates, the painting also legitimized Philip’s attraction to young women, represented in the painting by the youthful Amphitrite. Philip may have considered his status first as Admiral of the Netherlands and then as Bishop of Utrecht to provide latitude for making this claim, for the occupation of elite positions afforded opportunities to push the bounds of normativity and decorum without much social risk. These roles, alluded to by Gossart, also reinscribed Philip’s power through assertions of a heteronormativity that sanctioned, or at least did not abate, his pursuit of dalliances with youthful paramours.

At the same time, prohibitionist discourses of moral theology that made bodily desire sinful were ubiquitous in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries—in literature, scripture, exegesis, sermons, and the visual arts. Indeed, Jutta Sperling has surmised that some viewers would have found images of the Virgin Mary in which Mary offers her bared breast and erect nipple to the viewer rather than the Christ Child to be erotically intoned (fig. 17).53 This iconography may have forcibly reinscribed expectations for sexual control, since their source was the immaculate flesh of the Virgin Mary. Moralist writing mostly for women mobilized the Virgin to comment on sexual behavior in ways intended to model the avoidance of sex acts other than procreation.54 I suggest that these works express a type of virtue ethics akin to that found in other contemporaneous images. Consider, for instance, the adulterous lovers Mars and Venus mocked by members of the Roman pantheon when caught in a sexual tryst by Venus’s husband Vulcan, a story that reaches back to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Tianna Helena Uchacz concludes that paintings on this theme, including one by Maerten van Heemskerck (1498–1574) (fig. 18), invited viewers to ponder the shame endured by the depicted couple and to adjust their own behavior accordingly.55

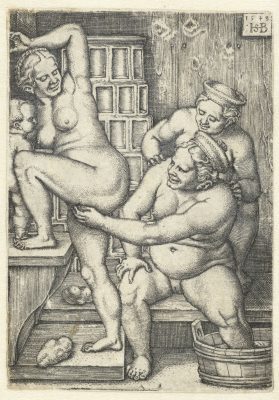

Unlike van Heemskerck’s representation of an illicit encounter in which Mars locks Venus in a sensual embrace, certain sexual subjects were beyond the bounds of decorum for explicit visual representation. Portrayals of sensual and sexual acts between men, and between women, are rare during this period. We can, however, make significant strides toward mapping the contours of attitudes about this subject through the few works that critique same-sex desire in explicit terms. A handful of examples are available from sixteenth-century Germany, in the form of prints and drawings by artists such as Hans Sebald Beham (1500–1550) and Hans Baldung (1484/85–1545). Linda C. Hults has demonstrated that some of the images Baldung produced for male viewers advance some of the strongest contemporaneous negative stereotypes about women, including images of same-sex female desire.56 An engraving by Beham, Three Women in a Bath (fig. 19), illustrates this perspective. The print offers a voyeuristic view of three nude women bathing, with one of the trio caressing the shoulders of another. The latter reaches up in turn to the genitalia of the figure at left, who turns back to yield to—one might say invite—her touch. Of course, the sponges strewn on the floor suggest a practical purpose, and hatching between the primary figure’s thumb and forefinger, as well as the curve of her hand, suggest that she perhaps holds a sponge. Lecherous expressions, however, and Beham’s unabashed exposure of erogenous zones, lend these interactions a pronounced lasciviousness. And yet more complicated conditions were likely with this example, beyond simply upholding heteronormative, and thus primarily homophobic, perspectives, for despite the production of these images for a male audience, it is likely that at least some female viewers would have had access to them as well, at least on occasion. One wonders about the reception of these works by women, which undoubtedly would have been varied and complex. Furthermore, it may be that explicit images like this were an exception because they presented risks to reputation that most entrepreneurial artists would not have wished to shoulder, nor would patrons be likely to commission images of this kind for similar reasons. In this context, reputation derived from and reinforced heteronormative patriarchy, such that what one does with one’s body, or how one thinks of what others do with theirs, are matters of social regulation.

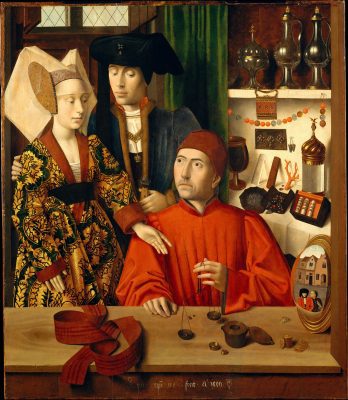

We now know that artists inventively critiqued same-sex practices by subtle means, through intonations, codings, and veilings, even as an especially challenging aspect of this research is understanding precisely when and how (the same may be said of gender as well: not all representations are as direct in upending the traditional signposts of the sexed body as Bosch’s Triptych of Saint Wilgefortis, and even then, the cues can be subtle). Subversive or resistant codes were important mechanisms for navigating heteronormative regulations, and thinking through them offers an alternative to the archives, which for this issue are fragmentary, exclusionary, and misleading. Take, for example, Diane Wolfthal’s insightful analysis of visual evidence and contemporaneous sexualized literary tropes that identify same-sex attraction in Couple in a Goldsmith’s Shop by Petrus Christus (1410–1475) (fig. 20). The falcon depicted with the two male figures at the lower right is an enduring symbol of love that conjoins the two sexually. Yet the couple’s image is reflected in a cracked mirror, a choice that at the time defined their relationship as illicit. Christus’s image thus may have provided a counterexample to sexual normativity, represented by the female-male coupling that resides at the fulcrum of the image, in particular regarding their marriage, implied by the wedding belt resting on the table in the foreground.57 Think, too, of the person extracting a bouquet from the anus of another in the central interior panel of Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (fig. 21), which likely alludes to sodomy.58 Along with the other autotelic activities in which the figures engage, and which the painting condemns, this motif deploys an indirect account to mark an activity as illicit. Bosch thereby advanced the desirability of heteronormativity through the application of visual coding.

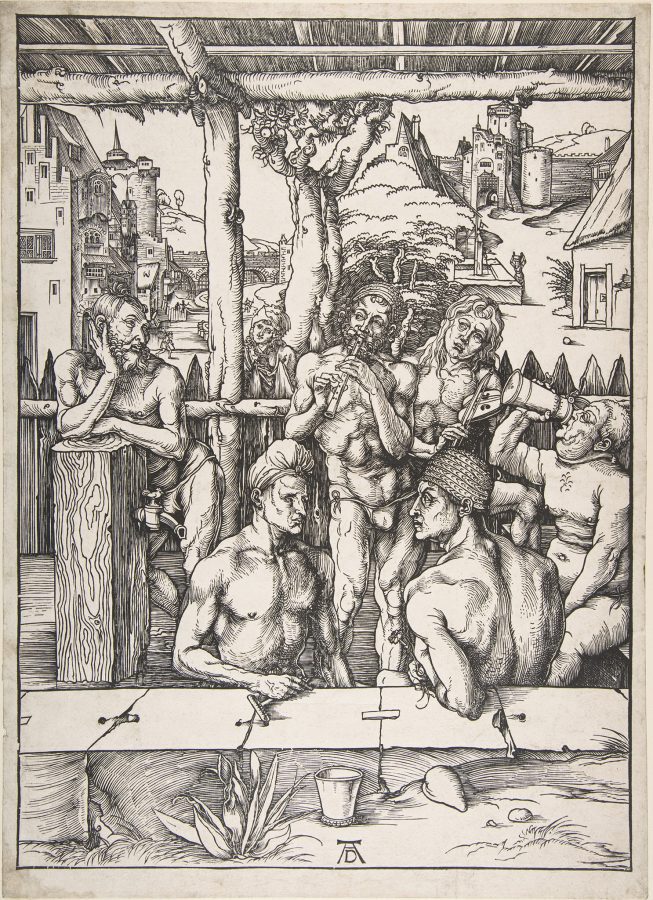

Not all images that we can surmise offered coded or intoned commentary on same-sex desire were decisively condemnatory, however, a situation that opens possibilities of sympathetic or subversive engagement. Scholars seem to agree that Albrecht Dürer covertly supported the idea of male-male attraction in The Men’s Bath (fig. 22). With a strategy of coding not unlike Bosch’s, he portrayed a phallically shaped spigot, topped by a cock and bowed to suggest an erection on the part of the leftmost figure, the direction of which implicates the two seated men in the foreground as objects of his desire. The bodily associations and proximities of this motif evoke the idea of sexual arousal among those present in this homosocial space.59 He also approached the representation of the scantily clad male bathers to emphasize their reliance on classical ideals, as Bradley J. Cavallo usefully argues. This strategy “imbricates homoeroticism with classicism” to suggest erotic desire while, at the same time, opening the option of “plausible deniability.”60 Equally void of condemnation, but deploying a very different set of visual strategies than Dürer, is a monumental brass representing Elizabeth Etchingham (d. 1452) and Agnes Oxenbridge (d. 1480) of East Sussex (fig. 23).61 This work offered Judith M. Bennett an opportunity to explore “lesbian-like” qualities in this unusual representation of two women together on a burial marker. Visual evidence supporting this line of thought includes the figures’ inward turns, unusual for commemorative images like this, and the incised folds in their hemlines that imply movement toward one another. These features suggest a coded commemoration of a deeper, intimate pair bond. A reading such as this, Bennett argues, resolves otherwise vexing problems of composition, figural representation, and dating of the monument. It also points to the potential of images to suggest a positive reception of this type of desire, even if they do so subtly.

The publications discussed thus far argue that early modern artists developed innovative compositions and cleverly adapted iconographical traditions to comment variously on same-sex desire. By contrast, I have taken up the subject differently, through visuality, an approach that understands interpretation as experiential, individualized, and fluid. Authors such as Sherry Lindquist and Alexa Sand are among those who consider visuality to recognize the cultural contingency of visual interpretation and, importantly, to historicize that experience in regard to subjective viewing practices and strategies.62 The value of visuality lies in its recognition of both the regulatory power of images and the possibility that individual interpretations can differ widely on the bases of geography, gender, class, sexuality, education, and so forth. In this, I consider it to emphasize more deeply than “reception” the specific nature of cultural dependency and the individualized formations of interpretation that result, even as the two approaches relate by foregrounding the viewer.63 Elizabeth L’Estrange usefully describes this interpretive latitude as “the situational eye,” a term that highlights the ability of viewers to form meaning through experientially acquired modes of understanding, which, as I suggest now, can lead to the exercise of certain kinds of interiorized agency about which we can productively speculate.64 Variations in experiences, skills, and strategies grounded in these bases can even result in interpretations that artists and patrons did not intend. This possibility extends the premises demonstrated in the discussion of the seals of Mary of Burgundy described above—the potential of making different types of meaning from the same visual cues—into the realms of gender and sex.

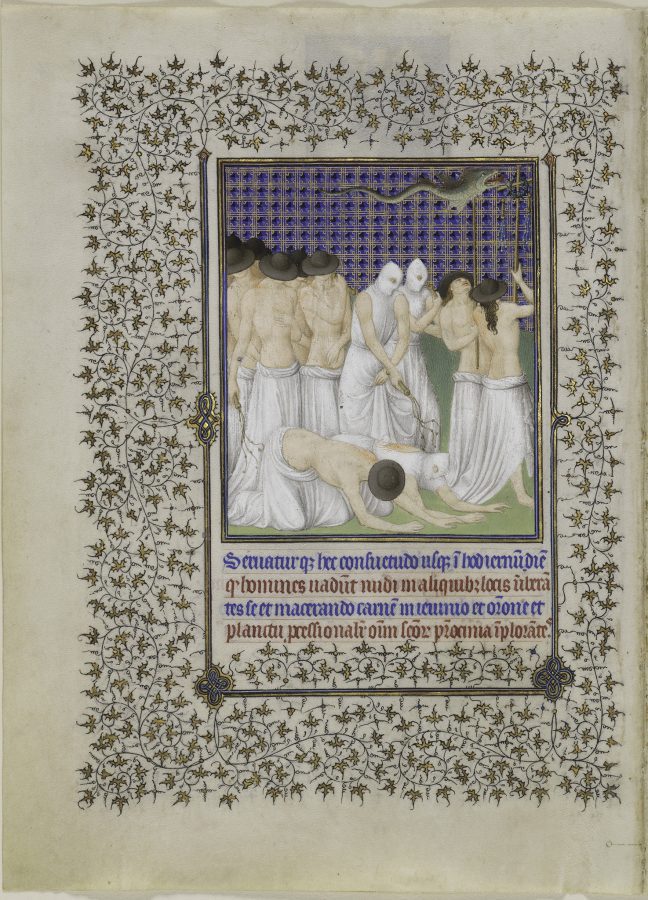

Visuality heralds new and imaginative ways to study subjects like same-sex desire for which we have oblique evidence, and in this it has much to offer. However, opening the scholarship to interpretive variety requires setting aside absolutes and embracing the possibilities of the full gamut of evidence at a scholar’s disposal, including evidence that seems indirect to us today. I made this point in analyzing early sixteenth-century representations by Antwerp artists of the infants Christ and Saint John embracing and kissing (fig. 24) during a Historians of Netherlandish Art workshop I led in 2014, as well as in publications that followed. My aim has been to suggest that the motif’s erotic valences could outstrip decorum to implicate same-sex desire for certain viewers, and that the multivalences of the theme offer space for both condemnation and tolerance.65 Since then, on a similar note, Sherry Lindquist built on earlier work by Michael Camille to conclude that sensualized nude male figures in miniatures in the Belles Heures commissioned by Jean de Berry from Herman, Jean, and Pol de Limbourg (d. 1416) (fig. 25) encouraged Jean to contemplate transgressive same-sex practices without necessarily condemning them.66

The studies I have referenced in this section are examples of “queering” the visual arts. This term has its origins in homophobia. However, in the 1980s, people identifying as LGBT—the acronym used at the time for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people—reclaimed it as a countermeasure to social bias (now, LGBTQ+ or LGBTQIA+ often are used to recognize those identifying as queer, intersex, asexual, and more). In the decades that followed, art historians and other humanists took up queer theory as a means to broaden the field.67 As things stand now, queer studies might investigate a range of evidence—direct, intoned, coded, veiled—as with the publications addressed above. Medievalist Karl Whittington notes in a 2022 essay that these directions mark a “return to the ‘open mesh of possibilities’ outlined by Eve Sedgwick’s famous definition of queer studies [of 1993], charting the wide range of meanings and interpretations embodied by objects rather than seeking to pin down or label particular historical identities.”68 Thus, current questions pertaining to medieval and early modern art do not often address whether particular artists identified as queer, or if artists coded images to suggest their own queer identities, a type of investigation that visuality, for example, reaches past. Most scholars maintain that queer identity did not exist in early modernity anyway, unlike in contemporary culture, but rather that people were simply engaging in a set of physical practices they found appealing (which could involve feelings of romantic love, too, of course), even as doing so opened different types of negotiations that historians are exploring.

We are in fact moving toward a model of profound fluidity, in which the historical process of negotiation is of central concern, both historically and methodologically. Whittington, for example, finds it productive to explore something adjacent to most current scholarship—the “physical interaction between artist and material” in creating sculptures of the nude form (assuming a male artist representing male figures)—to argue that “acts of making are sites that can themselves be read in sexual terms.” Once again, medievalists are leading the way by forging new paths with this work, although the prospect of broadening how we might queer early modern visual culture is gaining traction. The dialogue will accelerate with opportunities like that provided by Nicole Elizabeth Cook and Jun Nakamura, who organized a session on the subject for the 2023 conference of the Renaissance Society of America.69 We need more studies that fill out the unexplored implications of the existing work to push it in new directions.

Revising Agency

I have been inspired by the implications of visuality addressed above to revisit the concept of female agency discussed at the outset of this essay. “Situational agency,” the approach I offer, differs in certain ways from other recent critiques and revisions, which necessitate brief review in order to clarify the distinctions I have in mind. Two analyses of images that follow this discussion will demonstrate the value of situational agency for our understanding of visual culture in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

In a controversial essay of 2019, historian Martha Howell argued that female agency held consequence in history only if women were able to dismantle patriarchy.70 That has not happened, however: “Even the most aggressive challenges to patriarchal norms do not necessarily weaken, much less bring an end to, gender hierarchy.”71 Therefore, she concludes that the concept of female agency is fundamentally flawed. I see two main problems with Howell’s argument: methodological anachronism and an incomplete grasp of the state of the field. First, most early modern women had no intention of toppling the gender order with any act they attempted. Rather, they operated within the constraints of their time and place, even if sometimes with open resistance and without positive result, as discussed above. Second, specialists in early modern gender studies have been careful to do exactly what Howell asserts they have not: they have closely historized their subjects to demonstrate how women navigated limiting patriarchal systems even as they worked from within them. Scholarship of this sort is providing an increasingly rich and revealing account of the gendered landscape in visual culture. To name but one example, Dagmar Eichberger and Lisa Beaven have demonstrated that Margaret of Austria deployed her portrait collection strategically, at least partly to advance her political aims even as she answered to her father, Maximilian I, as regent of his Netherlandish territories.72 Close studies such as this can also make anomalies evident, enriching our understanding of historical situations and challenging the sweeping conclusions that wider-ranging projects can elide or misrepresent, especially where women and other understudied populations are at issue.73 Examples include the besloten hofjes of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwegasthuis in Mechelen discussed above (see figs. 4 and 5). Thanks to recent research, the hofjes are now understood to have resonated with specific and often conflicting historical pressures, such as the resistance to the reforms I outlined.74 This is quite different from the earlier, essentializing terms under which the works were evaluated by specialists. It is also precisely the kind of research for which Howell calls. Indeed, to insist that agency is present only when women have dismantled a discriminatory structure is to deny their agency—as artists, as subjects, as viewers, and as patrons.

Other recent critiques of agency are more productive. Theresa Earenfight, a specialist on queenship, has challenged binarism in agency studies. The problem with that approach, she argues, is that attending to which political players either had power or did not is doomed to conclude, simplistically, that men possessed it and women did not.75 Agency and other terms interchanged with it, including “influence” and “soft power,” therefore mark “the gendered gradations of power that subtly signal that an actor [a woman] is subordinate [to a man],” which “traps us into thinking about power in terms of masculine and feminine forms.”76 In a related development, historian Allyson M. Poska argues that early modern society encouraged certain “agentic gender norms” for women—ways in which women could act without undue risk—and from which women drew variously in navigating their situations and influencing others.77 This approach can help mitigate the archival silence regarding many women. It does so by presuming agency for all, recognizing that said agency must be defined not in some absolute sense, but relative to women’s circumstances in a given time and place. Of course, every facet of society in early modern Europe was dedicated to the regulation of gender and sexuality, and Poska rightly argues that women could choose to avoid agentic norms if they wished. Yet both men and women could reinforce patriarchal constraints. As Poska reminds us, “some women’s agency existed because of their ability to constrain the agency of other women.”78 In a related vein, Theresa Kemp, Catherine Powell, and Beth Link argue that female agency in early modernity can be identified only with a woman’s awareness: “Female agency refers to the actions of a woman who is aware of purposefully making decisions to act or speak on behalf of herself or a collective of which she considers herself to be a member.”79 The authors assert that accounting for awareness can counter claims that this research imposes the present on the past. The focus on awareness resolves this problem, they maintain, for it “enables us to apply the concept [of female agency] in a non-anachronistic manner.”80 This is a decidedly different formulation from critical fabulation, discussed above, for it relies on explicit evidence to document awareness.

My view of agency acknowledges the value of these studies while proposing a more flexible model that accounts for contextual differences, challenges of periodization, and agentic variety. To reiterate, I define agency as a situational form of power claimed by or for the socially restricted or disadvantaged, even if visible change was not, or is not, apparent. This approach has several merits. First, it softens binaries of agency, including those that bother Earenfight. I agree that the question should not be whether someone had power or not, for this framework suppresses its gradations and variabilities: even the politically powerful were comparatively bereft in certain circumstances. Rather, power was mobile, oscillatory, and persuasive—a “constellation of power” as Michel Foucault described it, even as he masculinized and ignored implications of coercion by focusing on the political, as Earenfight points out.81 Power in early modernity took different forms that were socially embedded. People exercised it to various degrees across time and space; and, for our purposes here, they deployed it in response to—or because of—perceptions of identity, categories of which were simultaneous, variable, and sometimes different from modern conceptions. Indeed, agentic power could be structural or personal, normative or non-normative as in Poska’s model, or some combination of both. Understanding such variability requires close attention to specific situations, especially when we analyze art making, patronage, interpretation, and display. Thinking more carefully and subtly about categories may help to break down “notions of binary gender/sex” as discussed by Spencer-Hall and Gutt. Understanding the intersections of gender/sex identification in visual culture for this period will continue to present a different set of challenges, however, in part because, with a few exceptions, artists were clear about defining bodies as female or male, for example through approaches to figural representation and sartorial accessories.

Situational agency has another advantage: it elevates marginalized people by naming their agency as power. Doing so not only exposes historical bias by acknowledging the underrepresented, but it also helps to correct a scholarly narrative that has tended to elide them. Its spotlight on inequity can expose and address bias and account for disadvantaged positions and conditions, thereby acknowledging that power can arise within constraints—constraints can in fact produce countervailing forms of power. Situational agency also allows for explorations in which artists presented imagined rather than historical figures. In a recent article, for example, I discuss matters of agency from four perspectives implied in images of fictitious women by the Housebook Master (active ca. 1470–1500): spectatorial, compromised, interventionist, and comparative, all of which could be considered iterations of situational agency.82 Investigations of this type are particularly challenging, for direct evidence that could be brought to bear on imagined characters is usually scarce or even absent. As I have argued throughout this essay, however, an aggregation of indirect primary evidence and/or the deployment of newer theoretical models are taking us past these methodological problems or at least giving us opportunities for critique. The alternative—ignoring images and populations for whom we have little or no traditional traces—cannot be sustained.

Finally, reframing agency as I propose resolves problems with periodization. Approaches to agency have traditionally identified intentionality and change as defining features, as if a person has agency when they act in ways meant to change—meaning improve—a situation. Earenfight defines agency as “the ability to take action that has the potential to affect one’s own destiny,” while Kemp, Powell, and Link emphasize awareness.83 Women were generally deprioritized in the early modern patriarchal value system, however, and therefore their activities, like the consequences of their efforts, often were not recorded. Even when they were, the records were less likely to be detailed or preserved for posterity, as discussed above, and certainly the information preserved could have been opportunistic, advancing the needs of the privileged. Furthermore, change often happened slowly and subtly, in increments or after a gap of activity that obfuscates the original source, making it difficult to attribute it to anyone. Neither can we document awareness in most cases of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, although more opportunities for doing so present themselves near the end of the sixteenth and into the seventeenth centuries, the focus for Kemp, Powell, and Link. Certainly, more information on acts and their outcomes is available for elite than non-elite women, especially women of political power such as those studied by Earenfight, and others perceived as influential by their contemporaries. Additional evidence about these individuals will emerge as research continues. Yet an exhaustive search across the archives would fail to uncover evidence for many instances in which we know or strongly suspect that women participated in visual culture: for the invisible labor they performed in artmaking, markets, and workshops; for their patronage and display strategies; and perhaps especially for their responses to images—for, in other words, their agentic interiority. Certainly, more archival information is available for later periods, and a 2022 call for a return to the archives to study European and American women artists from the eighteenth century and beyond, by Paris A. Spies-Gans, might make sense to specialists in these subfields.84 However, especially for earlier periods, predicating the agency of any restricted or disadvantaged person strictly on documented, and therefore visible, outcomes perpetuates the very systemic biases that suppressed them in history.

Two brief examples specific to the fifteenth century demonstrate the value of situational agency for the study of early modern northern art. Both come from my publications, where I have been exploring versions of this model for quite a while, even as this essay denominates and defines it explicitly for the first time. The examples involve portraits, which represent a particular type of problem for agency studies since they necessarily imply a certain agency for their sitters, especially when those sitters were also the patrons of the images. However, in some cases the depicted parties did not necessarily enjoy the same degree of control over the resulting image as Catharina van Hemessen did for her self-portrait (see fig. 6).85 Rather, a correspondingly broad range of possible motives were at work.

My first example illustrates precisely this situation. It derives from two essays in which I reinterpret illuminated manuscripts commissioned by the Burgundian duchess Margaret of York (1446–1503), who married Duke Charles the Bold (1433–1477) in 1468.86 Margaret ordered the volumes shortly after her marriage, a period in which, as part of her move to the Low Countries, she sought to understand the court’s expectations for her. The manuscripts guided her on expectations for her execution of the vita activa and the vita contemplativa (active and contemplative life) in accordance with her station as duchess. The one on the vita activa, the Benois seront les miséricordieux (Blessed are the Merciful, KBR Brussels, Ms. 9296), includes two miniatures, one depicting Margaret enacting the Seven Works of Mercy (fol. 1r) and the other of her praying before the Church of Saint Gudule in Brussels, in the company of the church fathers (fol. 17r). The volume on the vita contemplativa, titled Le Dyalogue de la duchesse de Bourgogne à Jésus Christ (The Dialogue of the Duchess of Burgundy with Jesus Christ), is embellished with a miniature of Margaret represented in a secluded chamber, kneeling before the resurrected Christ (fig. 26). It might seem logical to conclude that Margaret, as the patron, described how she wished to be conceptualized, and the illuminators complied. If so, she made powerful claims for herself as a representative of the realm to the people in religion and in her personal devotion to Christ, who has chosen to appear to her.

As my essays demonstrate, however, it was not Margaret but rather her advisors and artists who designed the miniatures. These individuals were invested in the success of the duchess specifically as a representative of her husband for the Burgundian polity, and they consequently imposed a regulatory program on her, one intended to achieve the court’s expectations. This new conception of the volumes’ origins might seem to leave Margaret bereft of agency, for it excludes her from a role in determining the contents of the manuscripts. We can identify and understand her agency in other ways, however, such as in her acts of gifting: she presented Le Dyalogue to her confidante Jeanne de Hallewin, and she later bequeathed the Benois to her step-granddaughter Margaret of Austria. Far from being incidental historical details, these acts should be understood within the context of women-focused reading communities. Such communities were thoroughly knit into the fabric of European courts at this time, and as a result they empowered participants. No less important is the context of women’s intellectual networks, as touched on above, in which the giving of a book was an act of empowerment. Viewed through the lens of situational agency, such contexts help us understand Margaret’s gifts and bequests as more than the simple transfer of material goods, even as they likely did not result in tangible improvements to her life or anyone else’s. Furthermore, if Margaret turned inward to activate her agentic interiority as a situational viewer, she certainly could have interpreted her portraits in ways the designers did not intend, ways that could have been self-actualizing and empowering for her. Those ways might be unknowable and unmeasurable for us, but we can, and should, nonetheless contemplate the possibilities.

The second example illustrating the usefulness of situational agency involves the Diptych of Marten van Nieuwenhove (fig. 27) by the Bruges painter Hans Memling (1430/1440–1494).87 An inscription on the frames that identifies the sitter has led specialists to conclude that Van Nieuwenhove commissioned the work and that he did so at age twenty-three. At this time, Van Nieuwenhove had yet to reach the standard for male maturity (age twenty-eight), and his age marginalized him situationally as the youngest in a family of older men who enjoyed records of considerable civic achievement.88 The iconography of this painting counters Van Nieuwenhove’s comparatively disadvantaged status by advancing a masculinity defined by sexual abstinence or even virginity, the contemporaneous ideal for unmarried men. This archetype ran parallel with one of several available to married couples, namely, chastity, or sexual abstinence in wedlock except for acts dedicated to procreation. Therefore, once Van Nieuwenhove had married, and as he and Margaret Haultains produced children, aspects of the lifecycle values advanced by the imagery may have pertained in retrospect, if this time in marriage rather than prior to it. Furthermore, the image functioned differently within the household once viewers like Hultains and their children became part of the viewing audience (assuming the diptych was either displayed or available in the home or elsewhere). This case underscores the importance of acknowledging interpretive variability over time and in response to changing conditions, without making change itself a defining feature of agency.

The example of the Diptych of Marten van Nieuwenhove also demonstrates that men as well as women might have operated from positions of relative advantage or disadvantage, an aspect of agency about which we need to know more. Asking such questions in no way jeopardizes a focus on women. This concern was expressed informally around a proposal to rename the Society for the Study of Early Modern Women to include gender, a move that some feared might jeopardize the focus on women by adding men to the mix.89 After several meetings and roundtables that invited debate, members of the society voted in favor of a change in 2018. Since then, the SSEMW has been the SSEMWG—“Society for the Study of Early Modern Women and Gender” (emphasis mine). To date, this revision has not shifted the focus away from women, narrowly defined, in any measurable way. If we hold in mind Joan Wallach Scott’s definition of gender as a “primary way of signifying relationships of power,” early modern patriarchy will return our attention to women again and again, even as we acknowledge instances in which women held power over men and as we explore the relationships between power and masculinity.

I close with a tantalizing possibility of a woman critiquing a man’s sexual proclivities through a commissioned image, an example that calls us to reconsider modern assumptions about the exercise and force of agency. This case involves Cimburga of Baden (1450–1501) and Hieronymus Bosch’s condemnatory The Garden of Earthly Delights (fig. 28). Paul Vandenbroeck has proposed that it was Cimburga, and not her husband, Engelbert II of Nassau (1451–1504), as traditionally maintained, who commissioned the triptych for their residence in Brussels.90 According to Vandenbroeck, Cimburga’s aim was to admonish her philandering husband and encourage self-regulation. Her putative patronage of a sexually charged image intended to rein in a husband breached contemporaneous—and contemporary—expectations for the motivations of patronage and iconography suitable for a woman. This is a far cry from assertions that advance the power of wives over their husbands through fictive persons depicted by male artists (I have in mind the “woman on top” topos exemplified by images of Phyllis and Aristotle). Works such as these may have seemed comedic to some, but for others they reversed traditional gender/power roles in ways that reinscribed male supremacy by presenting women as threatening. In the case of Cimburga, we have a historical rather than a fictive figure who exercised agency to admonish her husband, agency that she likely perceived as potentially beneficial for herself, whether or not the outcome was what she desired. This revisionist position on a canonical work reminds us to question preconceived notions about women as patrons and viewers and to consider recalibrating certain fundamental conclusions about early modern art through a gendered lens. The possibilities will make for an exciting future, one in which current assumptions about history, and the methods of analysis we might use, will be challenged and revised. Studies of that kind may soon render aspects of this essay obsolete. We will be all the better for it.