This state-of-the-field article surveys the economic histories of Netherlandish art. Tracing major contributions by scholars following in the footsteps of Michael Montias, we present the developments of art historical econometrics and consider the evolving ways in which economic analyses address topics such as supply, demand, price, labor, and form. We show the various applications of economic methods and pay particular attention to the interrelations between quantitative research and other modes of inquiry: archival, technical, biographical, stylistic, digital, regional, global, and so forth.

Preface

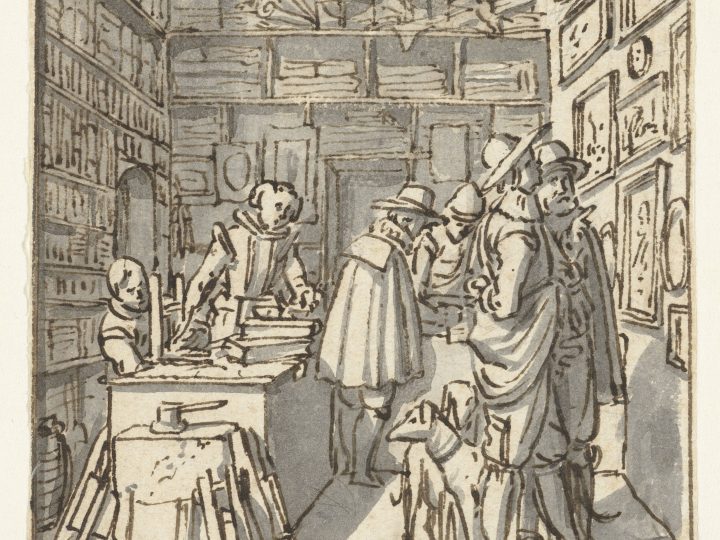

At the turn of the twentieth century, socioeconomic study was at the heart of the field of Netherlandish art history. In 1901, Wilhelm Martin defended the first Dutch dissertation on a purely art historical subject: “Het leven en de werken van Gerrit Dou beschouwd in verband met het schildersleven van zijn tijd.” In the same year, but working under a professor of economics, Hanns Floerke defended in Switzerland a dissertation on the Netherlandish art market, published as Studien zur niederländischen Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte: Die Formen des Kunsthandels das Atelier und die Sammler in den Niederlanden vom 15.–18. Jahrhundert in 1905.1 Beginning in the same year, Martin published a series of articles in The Burlington Magazine that included essays on the training of artists, the painter’s studio, the process of painting, and how works were marketed. And then it ended, almost as suddenly as it had begun: Martin became director of the Mauritshuis and turned to writing a different kind of art history, and Floerke did not pursue further work in this area. In 1947, art historian G. J. Hoogewerff published his important work on the Dutch guilds; it too generated little further research.2 It was not until the publications of Michael Montias, first his “Painters in Delft, 1613–1680” in Simiolus and then his remarkable Artists and Artisans In Delft: A Socio-Economic Study of the Seventeenth Century of 1982, that interest in this type of research ignited enduringly.3 Montias was a very different scholar than Floerke or Martin: trained as an economist of the Soviet bloc, he came to art history late in his career via a fascination with archives (fig. 1). Thus, although many of the questions he asked over the next several decades were familiar ones, from the older writers, he used different methods to answer them. He also ventured, importantly although delicately, into questions of how studio and market conditions impacted the appearance and even the style of paintings.

It is not the purpose of this article to delve deeper into these foundational works of the field, however, nor even to provide an overview of contributions to this field made in the previous century. For that, we direct the reader’s attention to the excellent article by Marten Jan Bok from 1999.4 Just before that date, in December 1998, a colloquium was held in Middelburg on “Art for the Market,” followed by the publication of a selection of those papers and several added texts as a special issue of the Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek.5 We have taken this event as marking a watershed moment, when not only economic historians but also many art historians—and teams comprised of both types of researcher—developed new questions about the socioeconomic shapes, processes, and pressures of the early modern Netherlandish art world. Our article therefore focuses on contributions from 1999 and after.

Introduction

The emergence of open art markets in the Netherlands revolutionized the business of buying and selling art across Europe. Having evolved from medieval trade infrastructures, these markets and their sustained success depended in turn on numerous interrelated social and economic transformations. More diverse classes of consumers, wielding increasing purchasing power, began acquiring paintings and other luxury goods to decorate their homes. This burgher demand, characterized by tastes and interests that diverged from ecclesiastical and noble patronage, created the conditions for a highly segmented market. To attract this more heterogeneous clientele, artists diversified their products, invented novel subjects, and experimented with new materials and formats. Competition for market share promoted specialization, collaboration, and creative partnerships. At the same time, the expansion of export markets within and beyond Europe encouraged artists to reorganize their workshops and streamline production, not only to satisfy growing demand but also to minimize costs and maximize profits. A new class of professional art dealers emerged to help facilitate sales, mediating between producers and consumers. These agents coordinated domestic supply with foreign demand, brokering both high-end deals and wholesale agreements and influencing tastes and trends in the process. The spaces where art was marketed changed, too. Retail venues, and the trade infrastructure they supported, became more specialized in displaying, handling, storing, and shipping particular types of products. Adapting to these transformed market conditions as both regulatory bodies and social corporations, artists’ guilds bent rules and instituted new measures to protect their members and control quality. Although shaped by international commerce and colonial expansion, early modern markets, like the art industries that sustained them, were situated phenomena, registering both the particularism of their urban circumstances and the political and economic dynamics that governed the overland and maritime networks in which they were embedded. Economic historians of art have produced important studies of all these different facets of the Netherlandish art market.

A primary task of economic art history has been to reconstruct the historical dimensions of the art trade through empirically driven research. Drawing on archival sources that had been compiled, published, and synthesized in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the first studies to use economic methods to discern measurable patterns in the historical record were published in the 1970s.6 Given this archival orientation, studies of the art market, since the foundational works of Michael Montias, have been defined by micro-historical analysis focused on specific Netherlandish towns and their trading networks.7 Although hardly inevitable, two peculiarities in this literature persist. First, rather than pursuing multinational inquiry, even comparative research in the field has tended to focus either on the rise and decline of art markets within the Netherlands or the transmission of Dutch and Flemish business models via emigration.8 Second, economic historians of art have rarely reconciled their data with period concepts or intellectual history, privileging the analysis of market functions over and above the social significance of art markets historically.9 Nevertheless, scholarship in the field has, within the past twenty years, significantly revised our understanding of how local developments and regional production evolved in relation to the expansion of international trade. This essay begins by charting recent studies of Netherlandish art markets, broadly conceived, and situates these studies within several trends that connect research in the field. Our focus is on art historical contributions that use economic methods, which treat objects and their makers as socially engaged actors with quantifiable traits related to mechanisms of production, consumption, and the distribution of wealth.

Growing Economic Data

In recent years, data analysis in the economic history of art has evolved in important ways. A few major datasets, compiled over a period of years, have generated interpretive studies that are ongoing. Foremost among these are ECARTICO, based at the University of Amsterdam and initiated within a project led by Eric Jan Sluijter and Marten Jan Bok; and Project Cornelia, based at the University of Leuven and initiated by Koenraad Brosens.10 Each began as part of a relatively limited project, the former in 2007 to gather data on Amsterdam history painting and the latter in 2012 for work on networks of tapestry production (fig. 2). Project Cornelia now describes itself as a project for “slow” digital art history. By this they mean that all their data is gathered from archival sources, so that the oldest kind of research joins the newest. Incorporating into its dataset all “actors” in a documented “event,” however peripheral, Project Cornelia visualizes and analyzes data as networks to uncover interesting trends, such as the crucial role of women in the formation of tapestry networks.11 ECARTICO now contains data on fifty-five thousand persons connected to the cultural industries of the Low Countries in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a vast dataset that allows for a range of investigation. These two databases have opened the way for more data-intensive economic inquiry, resulting in a series of publications highlighted below.

Marketing Mechanisms

Galleries, Auctions, and Lotteries

Among economic historians of art, there is broad consensus that the initial phases of the commercial revolution took place in the Southern Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, first in Bruges and then in Antwerp, where the medieval fair cycle and staple markets laid the commercial foundations for robust international trade. Regional migration was also a crucial force in the development of the art market. While the growth of Antwerp’s art industries in the sixteenth century depended on the influx of regional artisans and merchants, who introduced new products and strengthened commercial ties to other urban centers, the waves of emigration that followed the Fall of Antwerp helped shift the entrepreneurial center of the art market northward, principally to Amsterdam. Although the interconnected rise-and-decline of Netherlandish art markets, evidenced partly through demographic transformations, remains one of the dominant narratives in the field, recent scholarship continues to offer complicating evidence that gives greater texture to the longer durée of artistic production and consumption in the Netherlands. Scholars have come to treat northern and southern art markets very differently. Whereas studies of art markets in the Dutch Republic have focused on the market for paintings and, to a lesser extent, prints, studies of Flemish and Brabantine cities have observed the enmeshment of the market for painting within other luxury industries—furniture, tapestries, sculpture, decorative arts, books, prints, and even exotic collectibles.

Throughout the sixteenth century, retail outlets in Antwerp became increasingly specialized and better adapted to coordinate local and regional supply with foreign demand.12 Following the pioneering work of Neil de Marchi and Hans Van Miegroet, who first used economic methods to demonstrate the vitality of seventeenth-century Antwerp export markets for painting, Filip Vermeylen has produced numerous archivally rigorous studies of the Antwerp art market in its earlier phases of development.13 Vermeylen’s Painting for the Market (2003) provided the first major account of the commercialization of the Antwerp art market, examining the evolution of retail infrastructure that supported the international art trade from the fifteenth-century panden (galleries) to the establishment of the schilderspand (painters’ galleries) sales gallery in the Nieuwe Beurs (New Exchange) in 1540.14 De Marchi and Van Miegroet’s work on the Mechelen-Antwerp export complex established how this retail infrastructure sustained intricate regional relationships that impacted production and distribution in discernable ways.15 More recently, Aleksandra Lipińska’s study of alabaster sculpture produced in Mechelen for the Antwerp market explores the highly specialized and serialized production that supported the sale of luxury crafts on the open market.16 Koenraad Brosens’s research on the capital-intensive tapestry industry has similarly described the increasingly specialized sales facilities of the panden as institutions that helped manage regional ties between Brussels and Antwerp while offering the necessary credit to tapestry makers to facilitate speculative production.17 Brosens and his collaborators have also used data from the Brussels register in Project Cornelia to visualize patterns of economic behaviors and professional trajectories, which has in turn produced innovative thinking on guild regulation and engendered greater reflection on the challenges posed by current methods for gathering and interpreting data.18

The rise of art markets in the Northern Netherlands, and the collapse of the Antwerp art market, is typically ascribed to the mass emigration of Flemish artists and dealers after the Fall of Antwerp and the reassertion of Spanish Catholic rule. In a recent comparative study using the ECARTICO database, Nijboer, Brouwer, and Bok have offered a data-driven demographic analysis of the number of artists and craftspeople active in Antwerp and Amsterdam between 1500 and 1700, which indicates that the migration of artists did not significantly impact production capacity.19 Filip Vermeylen has also drawn on ECARTICO data for roughly one hundred artists who moved away from Antwerp; he has described the complexity of “regional” (e.g., Antwerp to Amsterdam) and “international” (e.g., Antwerp to London, Paris, Prague) migration patterns, positing that the emigration of artists was not solely driven by religious or political sentiment but by an array of factors, including familial and professional connections.20 Bruno Blondé has meanwhile demonstrated that the Antwerp art industries did not simply collapse due to emigration; they continued to flourish and evolve during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly alongside domestic craft industries.21

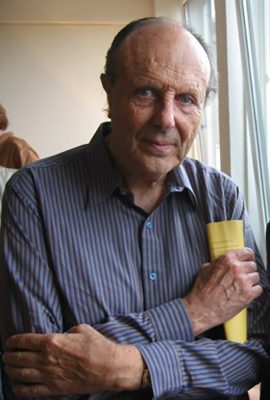

The market for paintings in the Northern Netherlands developed rather differently, having emerged without either the retail infrastructure provided by the regional fair cycle or a centralized sales venue akin to Antwerp’s painters’ pand.22 Dutch artists first sold wares directly from their workshops and adapted gradually to on-spec production by creating stock paintings for buyers to choose from. Through an analysis of documented sales records and other civic archival sources, Martin Jan Bok has argued that more specialized, dealer-run galleries gradually came to supplant artists’ workshops as primary sales venues for buying and selling art (fig. 3).23 As a result, art dealers and more sporadic marketing mechanisms—auctions, lotteries, games, and competitions—assumed greater significance in the Dutch Republic than in the Southern Netherlands. In her recent study of Amsterdam’s publishing and painting industries, Claartje Rasterhoff provides a lucid diachronic account of myriad local factors that shaped the rise of markets, fueled artistic innovations, and fostered the confluence of supply and demand during the seventeenth century. Taking into account the impact of mass immigration, she demonstrates the importance of spatial clustering for these creative industries, demonstrating that painters set up shop in close proximity to each other and their customers.24

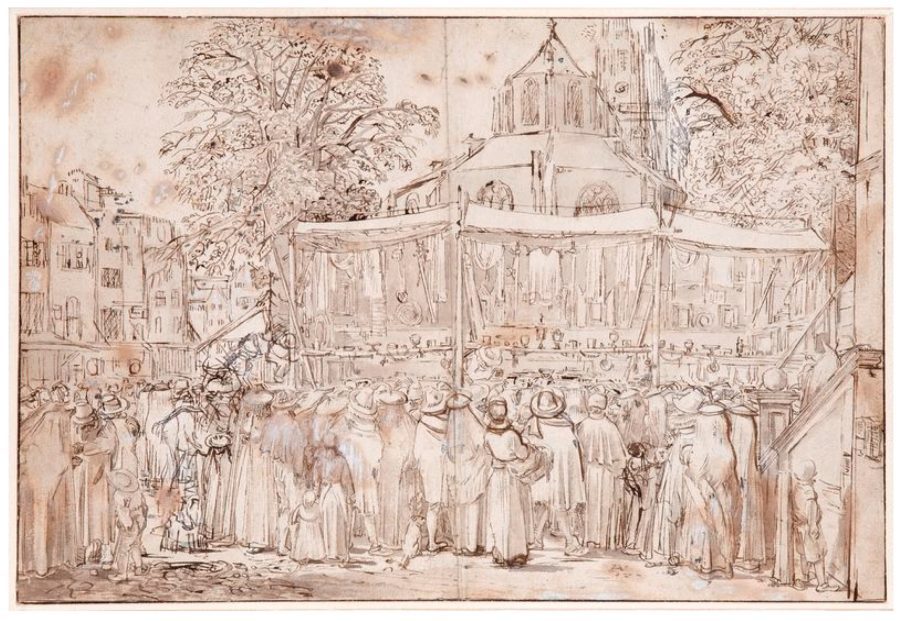

While the emergence of these different occasional marketing mechanisms suggests a climate of entrepreneurship fostered in the Dutch Republic, only lotteries and auctions have attracted sustained attention from economic historians of art (fig. 4). Most recently, Sophie Raux has excavated from relative obscurity the social history of the lottery as an institution invented to make profits and raise funds.25 For a nominal entrance fee, lotteries enticed contestants with the chance to win artworks and luxury objects. Raux reveals the entanglements of lotteries with dealers, guilds, and civic regulations, offering an analysis of the various objects that were offered as prizes. While the relative profitability of lotteries for their organizers remains difficult to quantify, since the amount of money generated by ticket sales was not always recorded, auction sales and auction-related inventories have become a key source for assessing the dynamism of the Dutch art market and its pricing mechanisms. Montias’s landmark study of auctions in seventeenth-century Amsterdam established the importance of the secondary art market as a barometer for gauging demand.26 Montias was also the first to use prosopographic data—that is, biographical information pertaining to the social, familial, and professional connections of a particular population—as an analytic tool for Netherlandish art history. In his quantitative and qualitative assessments of auction inventories, Montias inferred not only the wealth signified by the buyer’s purchasing power and the scale of the collectors’ liquidated estates but also the valuation of specific genres and artists’ work.27 Following Montias’s prosopographical methods, Rasterhoff utilizes datasets drawn from ECARTICO and the RKD (Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie), among other sources, to assess how patterns of spatial clustering impacted market organization, reconciling the numbers of active artists and their distribution across urban centers with artistic prominence and product specialization.28

Taken as a whole, these marketing mechanisms constituted the retail infrastructure that shaped transactions between buyers and sellers. The porousness and heterogeneity of this infrastructure as it evolved in both the north and south encouraged experimentation, risk-taking, competition, and adaptation. While such entrepreneurialism incentivized innovations, impacting both the organization of labor and product differentiation within artist workshops, the new modes of doing business also elicited increased guild scrutiny and protectionist measures.

Workshop Organization, Guilds, and the Labor Market

Netherlandish workshops were stratified enterprises where many specialized laborers were busy at work—apprentices, assistants, journeymen, and masters. While the business of the studio often extended through family lines, labor was organized hierarchically, and professional mobility was constrained.29 Guilds oversaw not only the training of apprentices but also the employment of assistants and journeymen as well as their professional advancement to master status. By setting general rules that limited the number of apprentices in each master’s shop, guilds prevented “free” labor from becoming a competitive advantage for popular masters while also securing employment opportunities for waged laborers.30 Guilds thus served a crucial role in the evolution of the art market by setting policy, managing membership, and controlling quality. As both trade organizations and administrative bodies, they regulated local industries while protecting them from external competition. In other words, guilds mediated the macroeconomic and microeconomic aspects of the labor market, playing an intervening role in both the organization of individual workshops and their production for the market.

Jean-Pierre Sosson and Michael Montias were among the first to assess guilds in economic terms.31 Describing the guild as a prototypical trade union, Montias introduced statistical methods that led the transition from data collection to analysis, thereby laying the groundwork for subsequent scholarship.32 Peter Stabel has examined guild statutes in Bruges and argued that those regulations protected artists from outside competition while fostering entrepreneurial experimentation and speculation; he has also studied guild laws in relation to the centralized marketing infrastructure of the fair.33 Meanwhile, Maximiliaan Martens has analyzed Bruges guild statutes and court records that regulated where artists were allowed to sell their work, illuminating some of the constraints that governed production for the open market.34

As labor organizations, craft guilds also registered the specializations of their constituents and worked to advance the economic interests of their members by influencing trade policy. Piet Bakker has highlighted the distinctions between the kunstschilder (artist painter) and the grofschilder (or kladschilder; coarse painter) in the formation of the Saint Luke’s Guild in seventeenth-century Leiden. By relating archival documents to changing conditions of the local market, Bakker shows how specialization and proto-unionization responded to demand and influenced the guild’s internal structure.35 Recentering the role of guilds in the efflorescence of art markets in Holland, Maarten Prak has argued that the structural reorganization of craft guilds was essential to artists’ collective ability to dominate local trade, innovate products, improve training, exchange information, reduce transaction costs, and better penetrate regional markets.36 Prak has also correlated guilds’ economic activities with their political agendas to show the impact that Dutch guilds had on both marketing and sales.37 Stressing the importance of spatial clustering in the cultural production industries of Holland—that is, how the colocation of artists within the city impacted innovation—Claartje Rasterhoff has studied the geographic distribution of painters and printers in relation to both guild regulation and market conditions.38

The economic history of craft guilds has also inspired research on workshop organization (fig. 5). Drawing data from guild registers, Maximiliaan Martens has charted the expansion of artistic production in Antwerp between 1490 and 1530, theorizing that the market was a “bottom-up complex self-organizing adaptive system” through which the guild maintained the balance between supply and demand by restricting apprentices’ access to the master’s status.39 Natasja Peeters has shown that while most apprentices worked as journeymen before becoming masters, many remained journeymen throughout their careers, never advancing to master status. As skilled wage laborers, journeymen provided a flexible workforce that contributed to the expansion of the art industry, but they often lacked the means to establish their own studios.40 Scholars have also examined the apprenticeship system in relation to guild regulations.41 Bert De Munck has challenged the common narrative that apprentices were part of the master’s household, a familial and domestic mechanism for professionalizing apprentices and assimilating them into the industry’s internal hierarchy. Reading guild regulations in relation to apprentices’ contracts, he asserts that apprenticeships remained largely contractual and that the increasingly businesslike nature of the guild might explain its transformed institutional identity, from that of a “brotherhood” to a juridical unit and industry organization.42

To make marketable products, workshops needed to acquire raw materials in ways that could cut costs and achieve a certain quality. Economic discussions of materials began in conservation studies that examined pigments’ costs and have now moved directly into economic work.43 Particular sources, costs, and values are often treated by specialists who focus on distinct materials, such as panels or glass.44 Koenraad Brosens has produced several publications that relate tapestry materials and processes to local markets.45 Filip Vermeylen has drawn on studies of the Antwerp art market to account for local workshops’ demand for pigments, colorants, dyestuffs, canvases, panels, and brushes; he suggests that Antwerp, as a net exporter of those materials, dominated the trade in both pigments and finished artworks.46 Bert De Munck has argued that, as dealers worked directly with journeymen to circumvent expensive masters, the added value of skill fell secondary to that of precious materials, which then led to the decline of artists’ guilds.47 Market preference, material costs, workshop practice, guild regulations, and human capital thus all took part in the art industry’s complex dynamics, as we are beginning to understand.

Supply

Producing for the Open Market

In addition to being a site of labor, the artist’s workshop was also an engine of entrepreneurship connected to the changing market. Although they practiced their craftsmanship within the confines of traditions, artists also reimagined and reinvented their businesses, responding to two main impetuses. On the one hand, artists experimented and took risks to identify subjects and invent products that were salable. On the other hand, they sought to produce work in new ways and with greater efficiency. Montias was the first to apply the ideas of “product” and “process” innovations as lenses to understand the ways that Netherlandish artists altered production for the open market, and his conceptualization has continued to inform art historians’ analyses of local market conditions, such as Vermeylen with Antwerp, and Sluijter and Jager with Holland.48 Process innovations entailed the adoption of various cost-cutting and labor-saving techniques that had been developed since the rise of oil painting. To produce more rapidly and reduce labor costs, artists used standardized patterns and stock figures that could be easily copied. Techniques of tracing and pouncing, widespread in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, allowed artists to recreate compositions many times over. Within the workshop, tasks were routinized so that different members of the workshop could focus on a discrete set of duties, which optimized efficiency. Vermeylen has described these process innovations as a “semi-industrial” workflow—a form of intra-workshop collaboration that entailed serialized methods of production.49

Workshop production mediated economic concerns and the manual practices of artists and artisans; consequently, conversations between technical and economic art historians have offered insights into mechanisms of supply.50 Open to both monetary and critical evaluations, style pertains to both the “process” and “product” of innovation, so that any external market pressure must also be contextualized with other facts and factors of an artist’s operation. The extraordinarily prolific Dutch painter Jan van Goyen (1596–1656), for example, has been the subject of analyses to do with both technique and profit (fig. 6). Looking at his applications of preparatory materials and paint pigments, Melanie Gifford focuses on Van Goyen’s famously “efficient” manner and argues that there must have been more than just economic motivations at stake, since his rapid strokes and limited palettes were “singularly well-suited to characterizing the local scene.”51 Informed by these technical assessments, Eric Jan Sluijter engages the rich data from inventories and sales to study further Van Goyen’s popular and critical success. As he argues, the profitability of van Goyen’s loosely executed Dutch landscapes was not merely a result of an inexpensive production method; the method itself was carefully chosen by the artist to continue a local tradition while quickly meeting the unparalleled demand for his autograph works in that famous style.52

Beginning with Lynn Jacobs’s work on Brabantine carved altarpieces, studies of the mass market for low-end artworks have explored both the aesthetics of multiplicity and the optimized production methods that allowed for market saturation. The production of compound altarpieces, as Jacobs demonstrated, entailed extensive collaboration between sculptors, painters, and joiners, each of whom employed various labor-saving strategies to produce work at the scale of demand. Configuring stock figures into particular sequences of biblical narrative scenes, the modular designs of these altarpieces entailed standardized modes of production, but they also enabled product customization and a novel interplay of media.53 Similar observations recur in the literature on the Antwerp Mannerists, who cranked out fashionable religious histories for the export market and for compound altarpieces; these largely anonymous masters painted with terrific economy, capturing in a few layers of oil the verisimilitude associated with the Flemish Primitives and Quentin Massys (1466–1530) (fig. 7).54 Subject to guild control, which regulated both the quality of materials and craftmanship, Brabantine altarpieces allowed buyers at the lower end of the market to “get the look for less.”

Streamlined production created the conditions for a mass market for paintings in both the Southern and Northern Netherlands. In his study of the mass market, Eric Jan Sluijter notes the ubiquity of paintings in Dutch burgher households; these domestic collections sometimes contained upwards of 150–250 paintings. He describes Dutch painters’ complaints against recent Flemish immigrants who were selling vast quantities of cheap paintings at city auctions around 1610.55 In their grievances, the painters leveraged accusations about surreptitious sales that were corrupting the market and asserted that copies were being passed off as originals. While these complaints became a driving force for the establishment of guilds in several Dutch cities, Sluijter posits that the competition ultimately encouraged Dutch painters to adopt various process innovations to lower production costs, demonstrating through comparative research into the prices of works sold that the Flemish paintings were comparably less expensive. Angela Jager’s recent book, The Mass Market for History Paintings in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam, picks up where Sluijter’s essay left off, recovering the understudied production of inexpensive history painting in Holland and offering a rich quantitative analysis of archival materials that also draws demographic data from the ECARTICO database and technical examination of paintings. Pointing to the explosive growth of the market for painting between 1580 and 1660, Jager studies the inventories of dealers who specialized in selling to the low end of the market as well as the serial methods for creating “dime-a-dozen” paintings, including standardized sizes and set iconographic variations of particular subjects.56

Demand

Collecting and Consumption

The rise of an art market was predicated on the increased demand for art and the increased purchasing power of a range of new consumers. Although sometimes described as “bourgeois,” the social classes captured by this term were far more diverse, encompassing not just members of the urban patriciate and lower nobles but also professionals and tradespeople as well as landowners and affluent burghers from various backgrounds.57 These collectors, who willingly spent their disposable income on artworks and luxury objects, complemented established, commissions-based patronage, which had traditionally sustained the most prominent artists. Studies on the demand side have considered a wide range of issues, including the quantity and quality of artworks in middle-class households; changing models of consumption and consumer behavior; the impact of trend, novelty, and fashion on interior decorating; and the emergence of cultures of connoisseurship and collecting. Though deeply informed by economic thinking, exploration of these topics, relying in some instances on scant documentation, has not always permitted systematic economic analysis.

Various types of inventories allow historians to assess the collections of sixteenth-century Antwerp households and observe the diversity of subjects represented, the copresence of paintings with other types of objects, the placement of artworks in different rooms, and overall shifts in consumption patterns over time. In his study of how elite patrons impacted the art market in seventeenth-century Antwerp, for example, Bert Timmermans explores not only the motives behind powerful families’ artistic investments but also the larger roles that members of these families played in the art world, particularly as intermediaries and central figures in networks.58 Bruno Blondé and his collaborators have studied consumer preference in Antwerp in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, focusing especially on material culture, changing constructs of value, and the multiplicity and coexistence of luxury markets.59 For the Dutch Republic, Marten Jan Bok has shown that rising incomes were a decisive factor in the emergence of a mass market for paintings, indicating that the secularization of demand, coincident with confessionalization, influenced spending habits and trends in interior decoration.60 In her important, newly translated study of household inventories in Leiden, Willemijn Fock provides an account of the professional classes that purchased art, how household wealth impacted the locations where paintings were displayed within the home, and shifting preferences for particular genres and artists.61

Although cultures of connoisseurship and collecting were inextricably linked to the rise of bourgeois consumption, quantifying their influence on the market has proven elusive. Sluijter has indicated that connoisseurial interests in buying autograph works by the master, rather than studio works, played a determining role in shaping pricing—and that artists’ reputations were an important factor.62 He also indicates that the patronage of art lovers (liefhebbers), who emerged as early adopters of novel Dutch genres, allowed artists to charge more for their work. Bok has similarly noted how patronage registered cultural transformations and reconstruction after iconoclasm in the Southern and Northern Netherlands: in Flanders, the redecoration of churches was the most significant driver of demand, but in Holland liefhebbers supported the creation of novel genres of artworks.63 Treating the liefhebbers as both a commercial clientele and a social class, Angela Ho has considered the ownership of high-quality paintings as a form of cultural capital, so that the interaction between some successful genre painters and their buyers can be understood in terms of consumer behaviors that preferred novelty and in turn encouraged artistic innovation.64

Increasing attention has gone to the Dutch household as both the consumer and subject of art. Economic historian Jan de Vries coined the term “Industrious Revolution” to explain how households’ economic behaviors might account for European (especially British and Dutch) economies’ steady expansion even before the Industrial Revolution. According to De Vries, British and Dutch families were already buying large amounts of commodities in the mid-seventeenth century, so much so that more family members had to work more, earn more, and finally buy more.65 De Vries’s theory has informed art historians who see the Dutch art market as part of a larger consumer culture. Julie Berger Hochstrasser has particularly adopted this demand-centric model and compared paintings to other commodities that made up Dutch material culture. By relating pictorial genres to patterns in domestic consumption, Hochstrasser shows how ideas of prosperity and material control appear in paintings’ subject matters and interior locations.66 Regarding the same consumerist phenomenon, Wayne Franits has studied domestic themes in the seventeenth century, when ideas of affluence, stability, and global expansion allowed an aristocratic class consciousness to be seen in genre paintings by artists such as Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) and Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684).67 Taste, hard to quantify in economic terms, has thus been posited by many art historians as a mechanism by which consumers (especially Dutch households) and suppliers (artists) communicated with each other to generate product innovation.

Art Dealers, Export Markets, and Artists’ Mobility

The expansion of export markets and the development of more specialized retail infrastructures created the need for intermediaries who focused on multiple aspects of the art business. Yet the art dealer’s profession in its earliest iterations was inchoate, protean, experimental, and speculative. Like other merchants of the era, dealers behaved like vertically integrated, multinational companies, and their portfolios were diversified—they specialized not just in one type of art but offered a wide range of products for sale. More than simply facilitating sales between producers and consumers, dealers influenced supply and demand in salient ways, serving as distributive agents who helped integrate regional and international networks.

Montias laid the groundwork for economic analysis of early modern brokerage, theorizing that a need for art dealers in the Dutch Republic emerged from the growing chasm that separated artists, who had more specialized products, from buyers, who had become more discerning and developed particular interests.68 While Montias focused on domestic markets, Neil de Marchi and Hans Van Miegroet have situated the buying and selling of Netherlandish art in a global context, providing a comparative study of two vertically integrated Flemish dealers who were active in the transatlantic trade and the booming markets for devotional paintings after the Counter-Reformation.69 In addition to quantifying both the volume and relative value of shipments, De Marchi and Van Miegroet describe the different business strategies that these family firms used to gain a competitive foothold in the market—how the dealers developed tactics for dealing with uncertain demand and investment risks. While Antwerp artists adjusted their production in response to what the dealers were buying locally, the dealers’ export businesses depended on knowledge of trends and buyer preferences in Spain and the New World, sometimes relying on foreign agents and other times splitting their time between cities.

By using both a quantitative analysis of export markets for Netherlandish art, based on archival analysis of Antwerp tax records of shipments from the 1540s and 1550s, and a qualitative account that situates these international commercial developments within political and religious circumstances, Vermeylen has shown that the international traffic depended on both local art dealers and foreign merchants. In a comparative analysis of the countries of destination, he demonstrates that the largest importers of Flemish luxuries were Spain, Portugal, and Germany, followed by England and Italy.70 He also studies the types of artworks exported to these different markets, noting the significance of Antwerp as a distribution point for both locally and regionally produced luxuries, including paintings, tapestries, sculptures, books, prints, and musical instruments. Charting the emergence of art dealers in archival documentation (certificatieboeken and liggeren), Vermeylen distinguished between high-end dealers, who financed and brokered luxury commissions for nobles and royalty, and low-end dealers, who developed less capital-intensive businesses by reselling locally acquired works—paintings, prints, sculptures, and miscellaneous pictures—for the open market, especially for the schilderspand. Although guilds were slow to distinguish between dealers specializing in different products and did not distinguish at all between dealers who traded locally or internationally, Vermeylen notes that many of the known dealers had strong family and personal connections to arts trades, and that other family members—wives, widows, sons, brothers—played roles in the distributing and marketing. These networks favored collaboration over competition, not only between artists or artists and dealers but also between dealers themselves.

As many art-dealing businesses were organized through familial connections, profuse archival records have enriched our knowledge of commercial endeavors that spanned generations. The Forchondt family ranks high among the most prominent Netherlandish art dealers of the seventeenth century, and Sandra van Ginhoven has undertaken a comprehensive analysis of the firm’s correspondence and business records, visiting archives in Belgium, Spain, Mexico, and Peru.71 Like other art dealers, the Forchondts maintained careful control of the chains of production and distribution: their portfolio included not just paintings but also furniture, textiles, jewels, and other luxury goods. Van Ginhoven offers a systematic microeconomic study of the Forchondts’ business strategy, noting not only the scale and scope of their activities in Antwerp and Mechelen, their reliance on an extensive intra-European and transatlantic network, and their strategies for minimizing costs and risk but also how the sheer volume of exports illuminates the transmission of Flemish imagery to New Spain. Regarding the Dutch art trade of the seventeenth century, Friso Lammertse and Jaap van der Veen provide a thorough account of the Uylenburgh family, whose business stretched from Poland to Amsterdam and London. With microscopic detail, they trace the Uylenburghs’ biographies over time to examine the evolving interactions among several aspects of the art trade, from artists, buyers, and suppliers to creditors, clients, and business partners.72

The movement of artists is another significant factor in the development of Netherlandish art industries.73 In the 1970s, Montias was already interested in the demographic composition of the Delft guild, whose members came from many regions in the Netherlands.74 Filip Vermeylen has linked the success of the Antwerp retail infrastructure to the demographic boom caused by regional migration to the city.75 In recent years, scholars have paid increasing attention to itinerant artists and their economic identities. Several publications show how artists of all ranks and qualities achieved commercial success in cities with high demands for labor.76 Many have studied England as a popular destination for Netherlandish artists.77 In recent years, more global perspectives have been introduced to Netherlandish artists’ movement. Marten Jan Bok has used the overseas activities of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) as a context for artists’ movement to Asia, their incorporation into local art production, and their relation to international trade.78 Deborah Hutton and Rebecca Tucker study the extremely mobile career of Cornelis Claesz. Heda (1566–1619/24), who lived and worked in South Asia as both an agent and artist; while they introduce the factor of economic motivation into transnational movements, they also complicate current methods of global art history.79

Pricing and Paradigms of Value

With the emergence of open markets came new paradigms of value. As an index of economic value, pricing provides economic historians of art with a concrete mechanism to correlate supply with demand—to gauge competition, labor value, material value, utility value, production costs, profit margins, market behaviors, and relative value. On the higher end of the market, collectors discerned the “hand,” or autograph work, of the master artist, but the lower prices commanded by studio pieces, copies, and knockoffs contributed to the vitality of the market, spurring artists to innovate, streamline, and take risks.

To assess pricing strategies, economic historians have used artists’ ledgers and studio notebooks, sometimes in dialogue with guild records and other sources, to draw data about artists’ productivity and pricing, which in turn provide a baseline for understanding marketplace valuation of artworks. In an influential essay, Martin Jan Bok posited that prices were an adjustable gauge of clients’ willingness to spend over and above the cost of production.80 Federico Etro and Elena Stepanova have built on this research to produce an econometric analysis of real pricing in the Dutch Republic over the course of the seventeenth century, which accounts for inflation. Their regression models demonstrate that prices peaked in the early seventeenth century, that phases of growth coincided with important periods of product innovations, and that the intense competition of the mass market and process innovations led to reduced prices and an overall decrease in the number of producers.81

Eric Jan Sluijter has meanwhile challenged the notion, prevalent in economic art history, that “art is a commodity like any other.”82 Elizabeth Honig has characterized this transitory state of the early modern art market as a conflict between two disparate systems of value: the honor system and the market system.83 Filip Vermeylen and Claartje Rasterhoff have, within a broader inquiry into the business strategies of seventeenth century Antwerp art dealers, described how discrepancies between subjective and objective valuation, or “quality uncertainty,” particularly as it related to questions of authenticity, created a source of friction between buyers and sellers.84 Altogether, these scholars paint a picture of a new but complex art market where value was created and measured in multivalent ways.

Copies, Variants, and Derivatives

Art history has always valued originals and originality. In the early modern Netherlands, identifying an object being sold on the art market as an original was central to its value, while in the twentieth century, the great narratives of art history comprised sequences of works that each evidenced originality. The stature of individual artists was determined by their inventiveness; copies and variants were of interest only insofar as they pointed back to a possibly lost original. But an economic angle can alter the degree of interest and importance accorded to copies and derivatives; it can, indeed, make them of unique interest in and of themselves. Not only do copies extend researchers’ base of art objects circulating on the market, but they can also tell us new things about old questions. A key move toward taking copies seriously was made by Neil de Marchi and Hans Van Miegroet, whose article “Pricing Invention,” a touchstone for scholars working on copies, calculated how much more an original was worth than a copy.85 What was the real value of originality in the seventeenth century? A more recent and very helpful study by Jaap van der Veen focuses attention on archival documents, from debates around authenticity to the terminology of inventories, to provide a framework in which the authenticity of Rembrandt’s work was evaluated in the Dutch Republic.86

The study of copies in Netherlandish art has extended to earlier periods. Replication has become a major focus of scholarship on sixteenth-century Antwerp. While Antwerp’s demand for novelty generated innovation and contributed to the rise of new genres, its production circuits had also developed a “replicative culture” quite early on.87 Recent work on Joachim Patinir (ca. 1480–1524) and Joos van Cleve (1485–1540/41) has positioned them as innovators—not just in style or subject matter but in understanding how best to navigate increasingly market-based demands. Two essays on Patinir’s workshop have taken different stances on how well he accomplished this. Arianne Faber Kolb sees him as a savvy manager who was able to differentiate between market segments and create replicas for some and derivatives for others; Dan Ewing argues, however, that Patinir failed to maximize the advantage of his innovative product and was only moderately successful as an entrepreneur.88 Ewing judges this based in part on Patinir’s relatively low output of copies compared to other artists, which suggests that Patinir had an innovative product but failed to create a marketable supply. Meanwhile, as Micha Leeflang has shown, Patinir’s contemporary Joos van Cleve was undoubtedly an expert in catering to the lively market for copies. After a downturn in the Antwerp economy, he turned from making expensive, multi-panel pieces to producing cheaper works for a broader public, and some of these compositions exist in an extraordinary number of versions—more than thirty in one of the cases Leeflang discusses.89

The artists whose replicative practices have received the most sustained attention are surely the members of the Brueg(h)el family. Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1638), long written off as a hack copyist of his father, has become interesting, but not because anybody has discovered hidden originality in his work.90 Indeed, Peter van den Brink is at pains to make clear that Pieter the Younger was not a “creative interpreter” of his father’s work; that sort of copying, as done by Pieter’s brother Jan (1568–1625), or by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), has long earned respect outside of the economic realm.91 But as Van den Brink’s groundbreaking 2001 exhibition Brueghel Enterprises showed, the goal of Pieter the Younger’s business was to supply an eager market with many copies of his famous father’s compositions from a generation earlier, at the height of the city’s cultural glory (fig. 8).92

In his focus on copying, Van den Brink emphasizes that Pieter the Younger was participating in a by-then longstanding tradition of efficient, serial production in Antwerp studios. Early in the sixteenth century, copies had achieved a high status as virtuoso replications of valued works, but in the mid-to-late sixteenth century they came to be seen as degraded, secondary objects on the market, and their value declined.93 Pieter the Younger was thus emphatically working for the low and middle sections of the market. Van den Brink’s conclusions are extended in the monumental, three-volume study by Christina Currie and Dominique Allart, The Brueg[H]el Phenomenon.94 They show that Pieter the Younger’s workshop was organized to respond to a market that was both intense and broad, so that good as well as mediocre copies were produced.95 Such a range of quality meant that the value of copies could also vary greatly: De Marchi and Van Miegroet’s calculations might need to be reassessed based on these data.

The nostalgic demand for more versions of the masterpieces of Antwerp’s Golden Age was not a unique phenomenon. Something comparable happened in the aftermath of the “Golden Age” of the Northern Netherlands as well.96 This later period was very little studied until recently—Bob Haak’s massive survey of seventeenth-century Dutch art ends in around 1680—and the economic turn has made post-Golden-Age art more interesting to scholars. Markets in this period took on a rather different shape, to which artists had to respond, and part of that response involved turning to copies, variants, and perhaps homages to works universally recognized as belonging to a marvelous but bygone cultural moment. The essays in Ekkehard Mai’s Holland nach Rembrandt were important for raising issues about this period, particularly (in the present context) an essay by Koenraad Jonckheere on the influence of the art trade and collecting on painting in Rotterdam around 1700.97 Jonckheere’s work on this period has focused principally on the auction of King William III’s paintings in 1713, and thus on the higher level of the art trade, but his research draws on source types not available for earlier periods, from Gerard Hoet’s 1752 catalogues of paintings sold at public sales to newspaper advertisements. He was able to document the exchange of more than ten thousand artworks, data that enabled him to cover the broader market and investigate auctions, agents, prices, dealers, collectors, experts, diplomats, and what we might call “value circuits” in this period.98

On the early eighteenth-century art market, copies and variants played an increasingly large role. This phenomenon has recently been treated in two books by Junko Aono and Angela Ho.99 Aono’s approach is more economic, as she sets the stage with a careful examination of market conditions between 1680 and 1750, a time of economic stagnation, growing wealth inequality, and a decline in the art market, caused in part by rather long-standing issues of over-supply. The number of buyers decreased radically and belonged to a small, elite segment of society; they had particular tastes (no more peasant scenes!), and artists cultivated a personal relationship with their “Maecenas.”100 Nevertheless, making copies was a huge business. In her chapter “Reproducing the Golden Age,” Aono notes that compositions by Frans van Mieris (1635–1681) were copied up to thirty-eight times, sometimes in his studio and sometimes long after his death (fig. 9).101 These copies were often not cheap, unlike those by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, and the better type had returned to the copy’s long-ago status as a substitute for hard-to-get works. Some were even made on commission, but most were market items. Willem van Mieris (1662–1747) was an energetic copyist, yet he was also an emulator, making new and very valuable paintings that satisfied a taste for Gerrit Dou’s rare works.102

Thus, paintings that largely or entirely lacked originality may have had little interest in the narratives of art history but were of great interest to many buyers—and hence many artists at various moments in our period. Print publishers, too, were invested in the possibilities of long-term replication, making new editions of prints from old plates long after the first printing.103 Plates are, as Alexandra Onuf puts it, “a publisher’s capital,” and even over generations a workshop could continue to produce as many editions as the market would absorb, with only the smallest updates in nods to current fashion. This is another type of artistic repetition that has only become of interest as scholars examine printing as a business enterprise.104 A final group who found predictable, derivative works attractive were the art dealers who liked a known quantity that they were sure would be salable.105 Artists who supplied dealers thus tried to make their works less innovative and more like something familiar. Perhaps, in fact, they worked to imitate a particular brand.

Brand Creation and Other Career Strategies

No single Netherlandish artist’s work spawned as many derivatives as that of Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450–1516). For generations after his death, Boschian works were a staple production area for painters—the anonymous and talentless but also the rather capable. Most famous is Pieter Bruegel (1526/30–1569), who designed pseudo-Bosch prints early in his career (fig. 10), but there are large quantities of prints and paintings that point to Bosch by their recognizable manner of invention and subject. Hans Van Miegroet coined the term “phantom copies” to describe works that, though actually originals, gain more value and better meet market demands by feigning a replicative relationship to nonexistent works by a famous master.106

Boschian prints and especially paintings are extremely interesting evidence for what we might call the market success of a particular brand. This is how Larry Silver framed them in his 1999 article on the “Second Bosch,” and since then other authors have also seen Bosch’s creation of a product that was simultaneously distinctive and imitable as a crucial aspect of his legacy.107 But Bosch is far from the only artist whose work is now thought of in terms of branding. As art historians increasingly look at artists in terms of their career strategies, market situations, productivity, and other economic metrics, the creation and control of a brand or a trademark product has been noted as one possible avenue that could be followed by a savvy artist in search of success.108 So, for example, Frans Hals (1582/83–1666) developed his famous loose, sketchy manner of painting early in his career in genre paintings made for the market, in part because it was economical and also because it allowed him to establish an identity in the crowded Haarlem art market.109 But Hals’s sophisticated clientele recognized in that bravura style a kind of virtuosity that was associated with the great painters of Venice and Antwerp, so his identity became that of a gifted and fashionable portraitist.110 At the same time, Hals trained his assistants to paint in this manner, establishing a quirky corporate brand that was, ironically, identified with his studio as much as with his individual hand.

In this Hals was not unlike Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), another artist whose success as a brand maker is a central part of his character in recent writings.111 The exhibition catalogue Rembrandt in Amsterdam from 2021 includes an essay on “Rembrandt as a Brand,” and several other catalogue essays have sections like “Building a Brand” and “The Rembrandt Brand.”112 Rembrandt’s personal career has often been analyzed in terms of economic decisions, an approach that his extravagant home expenditure and subsequent bankruptcy have invited. But only in 2006 did Paul Crenshaw publish the first extensive study of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy, in which he thoroughly situates the artist’s personal financial problems in the context of his particular behaviors.113 Other contemporary Dutch artists, Crenshaw notes, also had serious financial difficulties, but Rembrandt made different strategic decisions: his works appealed to a limited public; he chose to stop painting portraits (a sure income provider) for extended periods; and he failed to adapt during an economic downturn. In 2021, Crenshaw’s study was supplemented by a scholar from yet another field: legal studies. Bob Wessels, emeritus professor of international insolvency law, takes on Rembrandt’s entire forty-year career and examines all the artist’s legal and financial actions, problems, and conflicts, of which there were many.114 Dealing often with well-known facts or familiar documents, he reinterprets them based on his legal and financial expertise.

Colleagues, competitors, and former pupils of Rembrandt’s were better at reading the market and steadily producing items that would bring them incomes.115 Their career strategies were the subject of a project led by Eric Jan Sluijter and Marten Jan Bok at the University of Amsterdam, “Artistic and Economic Competition on the Amsterdam Art Market ca. 1630–1690: History Painting in Rembrandt’s Time,” funded in 2007.116 In his major book that lies at the heart of the project, Rembrandt’s Rivals, Sluijter gives a narrative in which ideas like “influence,” or even “inspiration,” are replaced with “competition,” which involves an artist’s conscious and deliberate self-positioning within the crowded world of the market.117 Quality, productivity, and innovation, he notes, all grow when there is such a clustering—what Montias had called a “critical mass”—in the cultural industries.

Choices in terms of style, subject, technique, and target audience may all be viewed as motivated by economic competition. As artists created work for various segments of the market, they found individual ways to distinguish themselves from the rest. Some tried to be as different as possible; some adapted to changing fashions; and some updated the styles of formerly popular painters to appeal to more conservative buyers.118 Others, as Erna Kok shows, became expert networkers who drew on an economy of “service and return” that networks foster.119

Competitive artists also used different strategies to establish a high monetary value for their work while keeping it distinct from that of Rembrandt, who, despite his financial problems, commanded by far the highest prices with the most discerning audiences.120 Part of the value of Sluijter’s work on this aspect of Rembrandt’s business lies in its use of concepts from the social sciences to explain why individual artists’ works look the way they do. This was a potential explored by Michael Montias largely from the side of production (cost of labor and materials); to this, Sluijter adds the side of consumption, showing how changes in the display and functions of artworks in different segments of the market were catered to by artists working in different styles.121 His article contrasting Govert Flinck (1615–1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680), and Rembrandt as history painters is a fine example of how this can work in a concrete instance.122 Several of Sluijter’s students have explored how a single painter might simultaneously work in several styles to appeal to different market segments: Judith Noorman demonstrates this in the work of Jacob van Loo (1614–1670), while Marion Boers shows that even so unlikely a candidate as landscape painter Pieter de Molijn (1595–1661) followed the same strategy.123

While competition contributed to product innovations, collaboration between workshops was not merely a process innovation, for it also engendered creative partnerships that boosted artists’ brands and advanced their careers. This was a particular habit of artists in Antwerp, and it is best known from the long-term collaboration between Rubens and Jan Brueghel.124 Natasja Peeters’s work on the Francken dynasty suggests that the mechanics of workshop production entailed extensive collaboration within and between family workshops and that stylistic variations between assistants and masters were not always suppressed.125 Less able painters collaborated for straightforwardly economic reasons—two specialists could make better livings by combining their minor talents—but the same motivations also held for independently successful masters. Enough data exist for a sustained economic exploration of this phenomenon, like the record books of Jan Brueghel the Younger, but no systematic study of collaboration from this perspective has been undertaken.

A project covering many artists’ career decisions is that of historian David van der Linden.126 He developed a database of 221 artists active in Antwerp in the 1580s, a number that enables him to analyze larger patterns rather than the decisions of individuals. His question is what artists did in a time of crisis: stay put and adapt, or emigrate? If the former, what did adaptation entail? And if the latter, to where? How did age, religion, and artistic specialty (painting, print, sculpture) matter to their choices? His study can engage in this sort of questioning because Van der Linden has created and utilized what is called “big data” by those in the digital humanities.

Digital Art History

Digital art history has, in the past few years, come to have its own corner in the economics of Netherlandish art. Mirroring Montias’s methodological innovations, scholars have used digital platforms to build, refine, visualize, and interpret large datasets related to historical art markets, as economists have long done in studying other forms of market formations and behaviors. From the production side, datasets have been useful in analyzing networks of makers: print designers, cutters, and publishers; tapestry designers and weavers; painters; and dealers. Often the accumulation of very large datasets has meant the inclusion of more peripheral members of the artistic community—apprentices who never became masters, wives and sisters who created crucial network connections, and so on. Big data can complicate historical narratives that were based on research on the most famous figures, forcing us to recontextualize those very figures and their roles in markets and networks.127 Two recent examples appeared in the 2019 special issue of Arts on “Art Markets and Digital Histories.”128 Each article uses, and questions, economic and social theory in interpreting art historical data. Harm Nijboer, Judith Brouwer, and Marten Jan Bok compare the painting industries of Amsterdam and Antwerp during times of crisis and, using social capital theory, show that the tightness of networks in Antwerp helped its industry recover quickly from the events of 1585, while the looser Amsterdam industry was better able to adjust to changing market conditions in the city after 1640.129 Meanwhile, in her innovative contribution to the volume, Weixuan Li combines ECARTICO’s data with the metadata from paintings catalogued at the RKD to study the number of painters active at different points in the seventeenth century, and the volume of works they were producing, asking why these numbers failed to decline at a point when, according to neoclassical economic theory, they should have done so, since the market was already glutted.130 Li argues that our mistake has been to expect economic rationality in the art industry when many other factors were at play, both for painters and for their publics. Painters took irrational risks because of what she terms a “social bubble” of overenthusiasm, misjudging their actual chances for success—but this was also a driver of innovation.

A fascinating project unconnected to these two datasets is that of Matthew Lincoln, who has set out to study networks in the world of printmakers using as his source the online catalogues of the Rijksmuseum and the British Museum.131 A single print neatly connects a designer, a printmaker, and a publisher: in network analysis terms, it creates the edges between these three nodes. Lincoln uses his data to analyze network centralization, one of the things that network visualization most clearly reveals and that has also been an issue in print studies. He shows that print networks could undergo rapid structural shifts and that the force of individual star players (Goltzius, Rubens) could effectively recentralize a network. Like other big data studies, Lincoln’s work reveals that some artists of much lesser renown were quite important in print networks.

All these projects using big data help redraw our sense of the larger picture of production and networks over time, and they bring out the roles of figures or groups who have been overlooked in traditional art history.132 Extended opportunities for this kind of research are being prepared by the project Golden Agents, funded by the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (NWO) under project leader Charles van den Heuvel. Golden Agents has gathered and structured enormous amounts of data pertaining to producers and consumers of the Dutch cultural industries.133 The resources they now unite as linked open data include ECARTICO, the Rijksmuseum, and the RKD, all mentioned above, but also much more: materials from the notarial archives of Amsterdam; the project ONSTAGE, which hosts data about the Amsterdam theater; the Bredius archival notes; and various sections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague. Hopefully the infrastructure that Golden Agents is building will support new research by art historians and historians for years to come.

Economics Now

The intersection between art history and economics allows us to address questions about Netherlandish art that neither the humanities nor the social sciences can answer alone. With the aid of data analysis, art historians can assess art objectively and interpret numbers subjectively, both avenues of inquiry that present exciting insights. While the economic method has refreshed the field of Netherlandish art history, the discipline of economics has also expanded since Montias first introduced it in the late 1970s. For decades, economists and economic historians have developed ways to reliably describe human interaction, psychological motivation, and social change, which are aspects of life that are keenly felt yet rarely put through quantifiable analysis, at least not until now.134 These are in fact topics that art historians have often tried to address with econometric considerations: How do people develop a sense of self and perceive its economic consequences?135 How do they evaluate their worth in a commercial world?136 How do artistic economies relate to wider trends of social change? How should scholars measure complex exchanges of goods, skills, and other capitals?137 How do creative agents form interpersonal bonds of both intellectual and monetary varieties, and how might novel analytical models such as Social Network Analysis (SNA) elucidate those relationships?138 As economists continuously innovate ways to measure the complexity of human connections, there is no longer any singular “economic method” but a profusion of frameworks, models, tools, and principles.

In the two decades’ worth of scholarship that we survey in this article, art historians have largely continued to engage with economics as it was understood in Michael Montias’s time and before. Without the quantitative support of data analysis, the invocation of economic considerations can become merely rhetorical, so that a general sense of monetary motivation is used to explain artistic behaviors in the broadest sense. But Weixuan Li, in particular, has shown the cracks in the classical assumptions about economic rationality, and her inventive, macroeconomic treatment proves that new analytical paradigms are not only viable but also necessary.139 So, the question is: Will art historians continue to understand economics in its rudimentary sense, or should we incorporate its new methods—and in the latter case, who can command both fields as adeptly as Montias once did? For now, and for those who still peer curiously into the copious data that Netherlandish art has to offer, many possibilities are in store.