Among the earliest visual responses to Rembrandt’s master print is Jan Steen’s Village Wedding of 1653. In it, Steen transformed somber and ill figures from the Hundred Guilder Print into raucously playful, joking, or drunk participants in the farce of a marriage ritual. In transforming the serious biblical subject into a comic village wedding, Steen departed from the general reverential regard for the print and demonstrated his respectful rivalry with Rembrandt.

During the early 1650s, Jan Steen (1626–1679) appropriated aspects of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print, creating one of the earliest visual responses to this masterwork (fig. 1). Well known to collectors as soon as it was made, the Hundred Guilder Print seems to have been rarely adapted by artists. In its invention and execution, it was inimitable, and its very fame meant that obvious references would be easily recognized. The work circulated among print collectors and at auction, presumably in a select and controlled way; as such, it may not have been easily accessible to an artist without connections to Rembrandt or to one of the privileged owners of the print. Steen may have viewed paper art and paintings in the commercial venues of The Hague, Leiden, and Amsterdam, and in the houses of private collectors. Given his enrollment at the University of Leiden in November 1646, he would have attended at least the last years of Latin school and belonged to the educated milieu of connoisseurs and collectors.1

The development of Steen’s paintings, in subject and technique, can be charted loosely according to his domiciles and contacts in Leiden, Delft, and Haarlem, and is indicative of his ambition as a universal artist. His training gave him experience in history painting, genre, and landscape, as he probably studied in Utrecht with Nicolaes Knüpfer, in Haarlem with Adriaen van Ostade, and finally with Jan van Goyen in The Hague. His earliest paintings are of village scenes that combine humor and keen observation in the vein of van Ostade, as in his Village Fair with Visitors from the City (fig. 2). In The Hague, where he lived until 1654, he sharpened his witty approach to village life, as in The Quack (fig. 3) and Village Wedding (fig. 4). While he was receptive to the various trends of portraiture, histories, and fijnschilder interiors, Steen consistently achieved his own formulation, in a comic mode, of these conventions. This is particularly apparent in the Dissolute Household, a domestic scene that might be considered a kind of sequel to the Village Wedding (see fig. 7).

H. Perry Chapman and Mariët Westermann have identified comic inversion as the guiding principle of Jan Steen’s art and placed his art in relation to the visual and iconographic traditions established by Isaack van Ostade, Thomas Wyck, David Vinckboons, and particularly Pieter Bruegel. They have also discussed Steen’s role-playing self-portraits as having an immediate precedent in Rembrandt and surveyed Steen’s interest in Rembrandt’s prints, notably the Hundred Guilder Print, which offered chiaroscuro and various figures to be exploited in The Village Fair, The Quack and Village Wedding.2 Steen found the Hundred Guilder Print useful for its complex design of light and shade, figure groupings on different levels with architectural elements, and the variety of physiognomic types. I suggest here that Steen’s Village Wedding may be considered as commentary on the Hundred Guilder Print, with a shared interest in marriage customs.

Steen’s regard for the Hundred Guilder Print may be considered pivotal for the compositional development of his art, even as it also opened up possibilities for subverting a serious image for comic purpose. In his earliest paintings, such as the Village Fair, the figures are arranged across the open middle area, in this case a seated man and woman with baby, as beggars, in the shaded center foreground. Tents at the left, a substantial thatched building, and a stage at the right form the backdrop for the small figures within an expansive vista. This painting is among those indebted to van Goyen and van Ostade and indicates Steen’s interests in theatrical production and the portrayal of an audience.3 The Quack differs from the Village Fair in its dramatic lighting, central activity elevated above a crowd, and anecdotal figures. These aspects appear to be the direct result of Steen’s study of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print.

In The Quack, Steen transformed Rembrandt’s Christ into the farcical healer, holding forth on a wooden stage, with an audience of two falsely pious monks, a boy riding a donkey, a fat burgher, and assorted other folk. Also on the stage is a seated man being poked and prodded by two “healers,” who are removing the stone of folly from his head. Most pointedly, the drunken lout in a wheelbarrow pushed by a boorish woman may devolve from Rembrandt’s ill figure lying on a mattress on a wheelbarrow, accompanied by a humble woman wearing an elaborate hood.4 By placing the main figures at the center, Steen departed from his earlier method of composing a village event, as in the Village Fair; such a central organization is reminiscent of the Hundred Guilder Print.

Just as pointedly, Steen regarded the Hundred Guilder Print as material for formal and thematic exploitation in his Village Wedding, signed and dated 1653.5 Steen substituted the solemn subject of Christ preaching, healing, and blessing for a humorous meeting of groom and bride for celebration after their marriage. He located the scene in a courtyard, surrounded by an inn, a ramshackle shed, and a wall with an arch; a massive round tower looms above. Beyond the arch are small houses and some trees, and in the distance, a church spire. The paved courtyard is a counterpart to Rembrandt’s setting of a massive yet vague wall and a barrel-vaulted archway with an earthen floor. Vines and grape clusters trailing over the inn and its portico are healthy variants of the sketchy foliage sprouting from the wall of the Hundred Guilder Print. Plants sprouting from the masonry of the tower above the uneven wall indicate a certain lack of maintenance but add rustic touches of greenery against the sky. Steen rendered the walls meticulously, articulating many of the stones and bricks, as well as the leaves of the overhanging plants. In fact, his very precision seems to correct Rembrandt’s indistinct wall and shadowy spaces in the Hundred Guilder Print.

As the bride, wearing white and blue satin, arrives with her two attendants, the groom leaps down the steps to meet her. Musicians, hanging out of the windows above, play various instruments. A man carries a basket of poultry over his shoulder and a chicken under his arm. In the foreground are a seated woman stretching her arm out toward a bawling toddler being grabbed by a girl, a young woman scattering flowers, and a boy kneeling to pick up petals. A motley and restless procession substitutes for Rembrandt’s quiet crowd and includes a man waving a stick at two fleeing boys, a woman holding a child by the hand, and a man carrying a child. Men clustered around the low brick wall at the left are jolly variations of Rembrandt’s Pharisees, who lean their elbows on the ledge. Where Rembrandt’s patient and sick audience awaits the solemnity of Christ’s healing power and wise words, Steen’s rowdy assemblage celebrates the union of a couple who appear mismatched in their enthusiasm for one another even as they enact gender-based roles.

Steen also followed Rembrandt’s example in his use of chiaroscuro. Sunlight hits the portico and the grapevines above it and picks out the sunflower in the terra-cotta pot placed precariously near the roof’s edge; light falls on the dog standing in the courtyard, the boy drinking at the fountain, and the musicians and onlookers at the left. Most intensely, the light hits the demure bride and her escorts, the paving stones in front of her, and the leaping groom; it reflects on the flower-girl and the nearby children. In contrast to the illumination in the Hundred Guilder Print that ennobles Christ and those closest to him, Steen’s pool of light gives only a unity of space to the newlyweds.

Steen’s howling and squirming toddler reverses the little boy holding his pancake away from a hungry dog in another Rembrandt etching, the Pancake Woman of 1635 (fig. 5).6 Steen’s child resists the clutches of the girl who tries to catch him. Such a vignette of distressed babyhood portends the vicissitudes of domestic life in the couple’s future.

Within the popular theme of the village wedding, Steen enhanced the rustic setting with symbolism; the grapes, which occasionally appeared in Dutch family portraits as a symbol for fertility, here might serve in that capacity, even as the vines are suitable greenery for the inn.7 The sunflower, turning toward the sun and away from the newlyweds, suggests an unpromising beginning and perhaps indicates their mismatch or forced union. Steen included a bunch of sunflowers when he painted another marriage episode, that of Tobias and Sarah; there they hang as happy decoration over the couple, whose prospects looked gloomy at the start but would be reversed with divine help.8

Other motifs in the Village Wedding suggest Steen recognized that Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print portrayed episodes from Matthew 19, generally acknowledged as the main text for the depiction of the three activities of Christ blessing the children, healing the sick, and debating with the Pharisees. The dominating narrative of Matthew 19 is the debate between the Pharisees and Christ over the Mosaic laws of marriage and divorce. With the men leaning on the ledge mimicking the postures and expressions of the Pharisees, Steen acknowledged the debate of Matthew 19, permissible divorce according to Mosaic law and the prohibition of divorce according to Christ’s law. By adapting the Pharisees into wedding guests, Steen repurposed the divorce advocators as marriage celebrants.

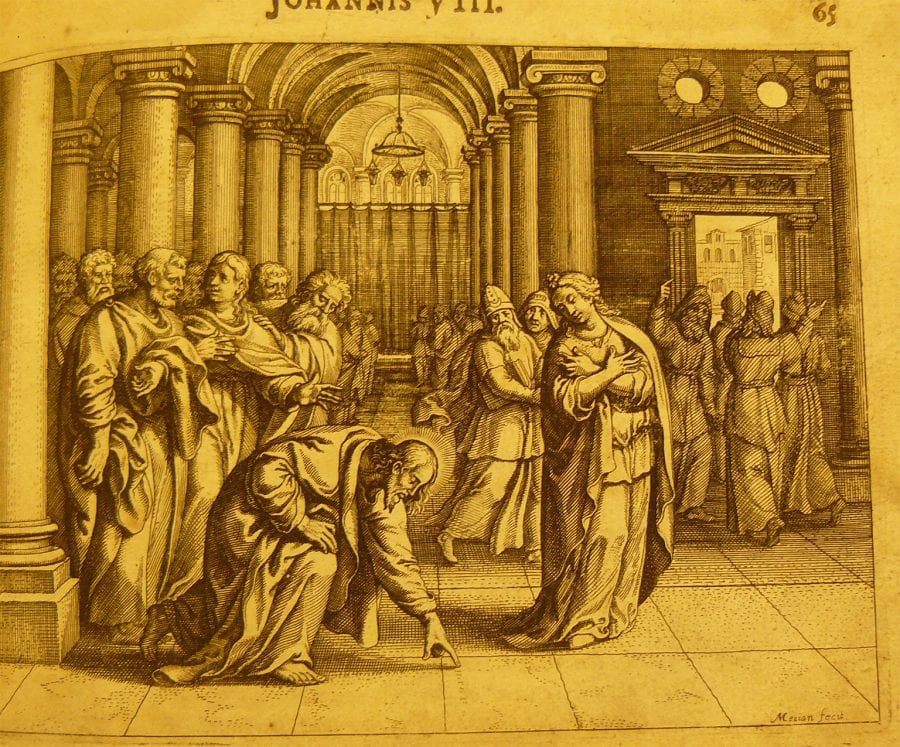

Another figure further suggests that Steen recognized the marriage and divorce text behind Rembrandt’s print. Steen’s boy, kneeling to pick up a petal, is here in a curiously associative posture: he echoes the pose of Christ as he inscribes on the temple pavement the words that spare the woman accused of adultery in many versions of this subject.9 One particularly close example is the engraving by Matthäus Merian in his picture Bible of 1625, a series reprinted several times (fig. 6). Both the boy and this kneeling Christ rest their right hand or arm on their knee. Although kinship of pose does not necessarily indicate a similarity of interpretation, the boy’s interest in the detritus from the bride’s entry implies an ambivalence about the ceremony. By placing an ignorant boy in the kneeling and pardoning posture of the wise Christ, who forgives the adulteress and her accusers in John 8, Steen hinted at the discussion about divorce and adultery in Matthew 19.10

Love and marriage are additionally mocked by the relief on the fountain of a man on horseback abducting a woman who protests. A sly insertion into the village scene, this relief is in the lower right corner, clearly discernible but not obvious at first. It is ambiguous whether Steen intended this as an allusion to specific characters in myth or history, perhaps Pluto and Proserpina or the Romans and Sabines. More likely, it is a generic reference to a woman carried off against her will symbolizing the lack of mutual consent.

Finally, even Steen’s pavement might be construed to have a symbolic value. The irregular paving stones become even more jagged at the center foreground, and several have deep cracks. The permanence of stone is in doubt, as fissures appear, and a few stones are missing at the edge. The general shape of this gap is reminiscent of the depression, which resembles a newly dug grave, in the center foreground of the Hundred Guilder Print. Cracks in stone might indicate transience and make the viewer wonder: how firm is the newlyweds’ union?

The Village Wedding is among the 40 paintings out of about 350 by Steen that is signed and dated, an indication of its importance within his oeuvre. According to Lyckle de Vries, the painting is a “leap forward” from his earliest works.11 It also hints at some of the future directions of Steen’s art: a crowd within an architecturally complex space, symbolism, and domestic life as an arena for morally ambiguous behavior. Steen’s study of the Hundred Guilder Print was formative in his development, and the Village Wedding presages his later interest in the aftermath of the marriage ceremony, which he frequently depicted as domestic disorder.

Life at Home

One exemplary vision of such a chaotic domicile, the Dissolute Household, belongs to the Metropolitan Museum (see fig. 7). Supremely at ease, the artist-as-patriarch flirts with a maidservant as she pours wine for the drunken lady of the house. Walter Liedtke has noted that this painting is a “catalogue of Holland’s favorite faults.” To paraphrase his choice words, these are Sloth, represented by the sleeping old woman; Lust, by the father; Gluttony, by food and tobacco; sacrilege, by the trampled Bible; gambling, by the backgammon board; along with personal vanity and poor parenting skills. Symbols of discord and disaster are the snapped lute strings and the overhanging basket full of items associated with poverty, ill-fortune, and illness. The cat prepares to pounce on the meat and a broken bottle lies on the floor. There is both luxury, in the well-furnished household, and warning, in the pocket watch on the floor. As the boy turns away the beggar at the window, “the encounter recalls the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31), in which a beggar is turned away from the banquet of a wealthy man. The latter eventually roasts in hell while the beggar goes to heaven.” The delight in portraying disorderly behavior is countered by caution.12

Even as Steen’s chaotic households include the artist as a merry and disheveled patriarch, they do not necessarily portray the reality of his own domicile, which, with six and then eight children and shaky finances, would not necessarily have been calm and orderly; rather, Steen crafted his image in these paintings to be consistently theatrically comic.13 Mocking social behavior within the family continues the mocking of wedding rituals.

Steen’s Regard for Rembrandt Anticipates His References to Italian Art

In several later paintings, Steen consulted compositions by Rembrandt, effectively to pay homage to them as he shifted placement and poses of figures, emphasis on characters, or moment depicted, so that his result is thoroughly original. Examples include The Dismissal of Hagar of ca. 1655–57 (Dresden, Gemäldegalerie);14 The Supper at Emmaus, ca. 1655–58 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum);15 and The Prodigal Son, ca. 1668–70 (private collection).16 Although Steen lifted the pose of the beggar woman in The Burgher of Delft and His Daughter, 1655 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum), from Rembrandt, he altered her clothing and expression.17 These examples of emulation indicate Steen’s sustained interest in Rembrandt’s art as a point of inspiration from which he could craft his own compositions.

Steen’s knowledge of and references to Italian art have generally been minimized. However, his familiarity with canonical Italian art is evident in some of his most elaborate paintings, in which he appropriated elements of works by Raphael, Veronese, and Bassano. For his Village School (Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland), Steen transformed the grand architecture and erudite philosophers of Raphael’s School of Athens into a jumbled schoolroom, with bored and raucous pupils and mediocre, uninspired teachers.18 For his Marriage at Cana (Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland), Steen constructed an Italianate loggia, reminiscent of Raphael’s Athens, and filled it with elegantly dressed couples, drunkards, and musicians. Both this Cana of 1665–70 and another version of 1676 (Pasadena, The Norton Simon Museum) adapt elements of Veronese’s grand canvas of the same subject (Paris, Louvre), which circulated in a 1637 etching by G. B. Vanni.19 Steen so varied and embellished his sources that only the cognoscenti would recognize how he played with the Raphael and Veronese exemplars. The Village School and the Cana paintings also adapt spatial arrangements and some figures from the grand prints after Jacopo Bassano’s “kitchen scenes.”20 These afforded strategies for organizing manifold activities within spatial constructions at dramatic angles, in contrast to the planarity of Raphael’s Athens.

Steen’s prominent placement of a plaster cast of Alessandro Vittoria’s Saint Sebastian in his painting The Drawing Lesson of ca. 1665 (Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum) can be understood on various levels.21 As a dynamic male nude, it is suggestively placed opposite the well-dressed young lady who is the rather dim pupil of the lesson. The Saint. Sebastian is a famed Venetian sculpture commissioned in 1563 for the church of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice. The sculptor himself regarded it highly, having several small bronze casts made of it, and included it in his own portrait by Veronese (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art). In The Drawing Lesson, the Saint Sebastian would have indicated the importance of Italian models for erotic teasing as well as didactic purpose.

With his references to illustrious precedents, Steen followed the prevailing concepts of appropriation that allowed, and even encouraged, borrowing from others’ work, as this demonstrated skill and erudition. However, it was understood that recognizably lifted motifs were only for the most excellent artists, whose own paintings would be judged superior to their precedents; less skilled artists were expected to disguise their borrowings.22 Referring to another’s composition but employing a different subject helped disguise the source and also could offer commentary on it. In the Village Wedding, Steen did both. He borrowed the crying toddler directly from Rembrandt’s Pancake Woman but he substituted the biblical gravity and authority on adultery, marriage, and the blessings of children in the Hundred Guilder Print with the frivolous celebration of a just-married couple. Confident in his abilities, Steen probably expected the toddler to be recognized as his besting of a Rembrandt motif. Whether viewers recognized figural elements of the Hundred Guilder Print in the Village Fair and Village Wedding is less certain. Steen’s approach to Rembrandt’s print in these two scenes of village life anticipates his later points of departure in the works of Raphael, Veronese, and Bassano.23

In his appropriation of thematic and compositional material from the Hundred Guilder Print in the Quackand Village Wedding, Steen also shifted from his earliest panoramic village scenes toward narrative with expressive figures. Steen’s references to the most expensive print of the century by the renowned Amsterdam artist Rembrandt brings out his sense of competition, as around 1650 Rembrandt was regarded with admiration. Apart from his works themselves, Rembrandt’s own sense of superiority in his art and in his personality made him a measure of achievement, to which the younger Steen could aspire in quality, fame, and success.

A young and ambitious Leidenaar, Steen understood that Rembrandt’s works were there to be mined for his own inventions, as Rembrandt’s pupils themselves did. In the Village Wedding, Steen created comic drama from a solemn and complex precedent. His approach to depicting the marriage ritual provides a humorous counterpart to the Hundred Guilder Print, itself centered on a discussion of marriage and divorce law.