The aim of this essay is to survey debates about early Netherlandish paintings as devotional objects from roughly the late 1980s to about 2020. During this period, an important shift in the study of this topic occurred: religious images were increasingly considered as devotional objects by virtue of how they were thought to have been used rather than how they appeared. In the last decades, questions about the functions of devotional imagery, about pictorial rhetoric, and about the responses that rhetoric might provoke in viewers, as well as its relationship to contemporaneous spiritual literature, have become core questions for subsequent scholarship dedicated to early Netherlandish painting. The essay concludes with a section devoted to research perspectives.

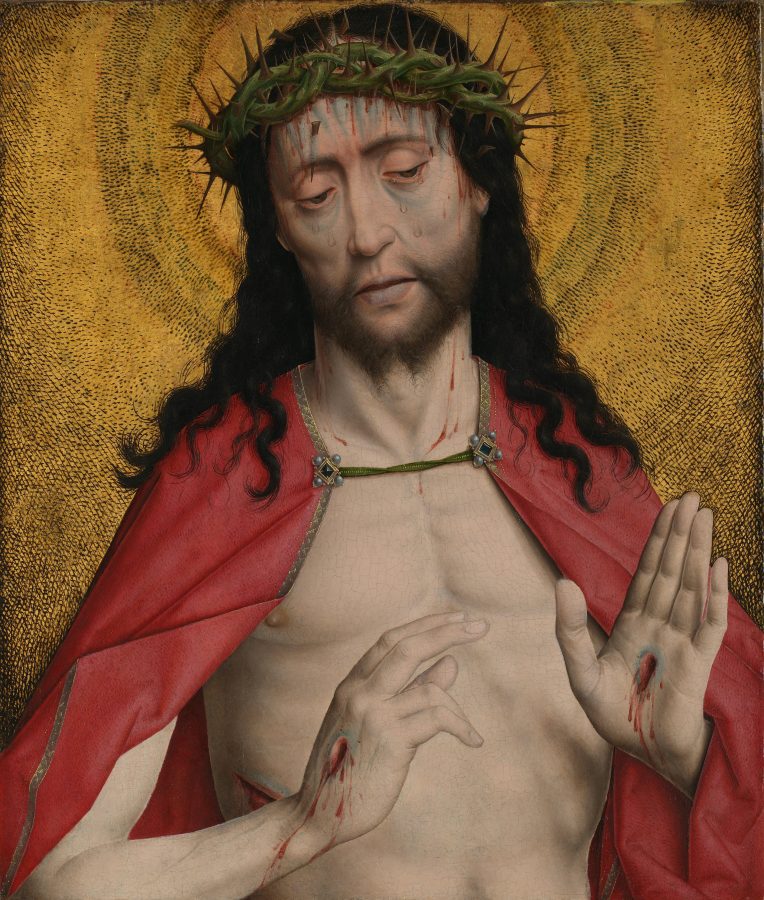

Netherlandish pictorial production of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries is most often thought of in terms of religious paintings, especially those commonly called “devotional images” or Andachtsbilder. The painting Christ Crowned with Thorns by Dirk Bouts (1415–1475) is representative of this phenomenon (fig. 1). Measuring a scant forty centimeters in height, it presents Jesus in bust length against a golden background. Crowned with thorns and wearing a red mantle that alludes to his Passion, Christ raises his left hand to show his stigmata, while initiating a gesture of blessing with his right hand. Although the gold background isolates the figure from its narrative context, the crown of thorns as well as the wounds on his side and hands all indicate that we see him after the Crucifixion. As did books of hours, such (usually small) pictures painted on wood or canvas became increasingly popular, especially among the laity, over the course of the fifteenth century. Produced first on commission and then in series by a growing number of Netherlandish painters, they were intended to serve various religious functions outside of the liturgical practices performed in church. Importantly, though, other kinds of religious paintings could also serve such non-liturgical purposes, as recent research that will be at the core of this essay has shown.

The aim of this essay is to survey scholarly debates about early Netherlandish devotional paintings from roughly the late 1980s to about 2020. During this period, publications on the topic demonstrated an important widening of perspectives and approaches, enabling scholars to more accurately situate images in their original visual and spiritual environments. Along the way, scholars also significantly broadened their definition of what constitutes a “devotional image.” And yet, recent literature simultaneously also maintains a certain dependence on ideas that have become classic, even conventional, having initially been formulated by groundbreaking art historians such as Erwin Panofsky and Sixten Ringbom. In the following pages, I will present an overview of the major recent trends in this subfield of Netherlandish art history and will identify research questions for the coming years. But before entering into the heart of the matter, a return to origins—namely Panofsky’s essay “Imago pietatis” and a reflection on the terminology initiated by it—are necessary.1

Published in 1927, “Imago pietatis” must be considered the founding impetus for the study of late medieval devotional art. As Daniel Arasse put it in the foreword to the French translation of the essay, Panofsky built “a ‘genetic’ approach of iconographical types” (une approche ‘génétique’ des types iconographiques) of the Man of Sorrows and the Mater dolorosa depicted in half-length, his aim being to retrace the genealogy of this type of imagery.2 In the first pages of the essay, Panofsky also attempted to define what he called the Andachtsbild, a term generally translated as “devotional image” in English. Such an image, he observed, represented Christ and/or the Virgin in close-up. From the standpoint of genre, this format is, according to him, neither a historical or narrative image (szenisches “Historienbild”) nor a hieratic or cultic image (hieratisches oder kultisches “Repräsentationsbild”). Panofsky’s “definition by opposition” concerns both the form of the image and its function or effect on viewers: narrative and cultic images establish an unbridgeable psychological distance, while the Andachstbild “makes possible a contemplative immersion (contemplative Versenkung) in the viewed content, that is to say, [it] permits the subject’s soul to meld with the object.”3 The Andachtsbild abolishes the distancing that we observe in the historical or cult image thanks to a modification of its content—in other words, by removing narrative elements from the historical image or establishing more proximity with the viewer than in the cultic one.4

As we will see, the Panofskian definition of the “devotional image” has profoundly shaped art historical studies on this topic. And yet, while his definition had a strong influence, the current state of research is that there is no consensus about what constitutes a devotional painting. Panofsky’s definition concerns both the function and the iconography of Andachstbilder. In later scholarship, however, the tacit but vague adoption of that definition has been questioned. So before focusing on recent scholarly publications, it is worth asking what “devotional painting” has meant for art historians over time.

What is a “Devotional Painting”? Scope, Terminology and Methodology

The basis for this article is a reading list I have compiled of publications (articles and monographs) devoted to “devotional paintings” produced in the Low Countries between about 1400 and 1550—in other words, publications that address in one way or the other issues about the functions, uses, and meanings of these objects in the spiritual contexts of their time.5 The very constitution of this reading list revealed that the definition of the topic of inquiry is problematic in itself. What is a devotional painting, according to scholars? Is the Panofskian term Andachtsbild still used, and if so how is it currently defined and applied? Is there a specific visual or material form that a devotional painting must take, or does the definition primarily concern functionality? How do art historians define devotional practices involving imagery? When dealing with paintings used in these practices, do they consider both personal/private and communal/public devotion? Should the present essay consider publications on altarpieces or epitaphs that have been studied in devotional or spiritual contexts—Jan van Eyck’s (1390–1441) Van der Paele Madonna and Rogier van der Weyden’s (ca. 1399–1464) Descent from the Cross being two particularly famous examples (figs. 2 and 3)? And so on.

In the course of my reading, a conclusion quickly arose: there is currently no real consensus (and perhaps not even an attempt at consensus) among art historians about what a devotional painting is and about what exactly might constitute devotional practices involving images. For a long time, the Panofskian definition prevailed, and art historians tended to organize a genre around a number of specific iconographic and formal elements that matched that definition (i.e., the small scale of the painting, close-up format, and non-narrative scenes with Christ or the Virgin). However, there is a growing sense that the devotional quality of an image depends more on its function and uses. And yet, a review of the secondary literature dedicated to early Netherlandish painting rapidly leads to the conclusion that when scholars cite “devotional images,” they most often refer to religious images (narrative or hieratic) used in the context of personal devotion (often called “private devotion,” although the term is not appropriate for the early Netherlandish context)6 and not collective or public practices such as those of, say, religious brotherhoods.7 In recent scholarly publications, devotional practices are usually understood as individual exercises, such as the recitation of prayers, meditational exercises, and pious readings aimed at nourishing the spiritual or inner life of the devout and their personal relationship with God. This is, in fact, a quite restrictive approach to devotional imagery, one that neglects other possible modes of inquiry, not least those regarding collective dimensions of devotion. In any case, it must be stressed here that in the field of early Netherlandish painting, when art historians speak of devotional imagery, they are almost always dealing with images intended for personal (individual) and not group use. Therefore, in the following pages, I will push back against that tendency in the hope that future research will address more vigorously the collective dimension of image-based devotional practices.

As for the issue of defining what is a devotional image, my aim is not to provide a precise definition—if that is relevant or even possible8—but rather to draw attention to the difficulty of such an undertaking as well as outline its implications for the present essay. Indeed, recent studies dedicated to “devotional painting” tend to show that trying to define devotional imagery tends to impoverish that imagery and does not reflect the actual uses of imagery in spiritual practices of the time. Beth Williamson’s study of Robert Campin’s (ca. 1375–1444) Madonna of the Firescreen (fig. 4) makes a good argument on this point. Williamson states that there is actually no difference between devotional and liturgical images, which instead operated on a continuum:

There can be a tendency to categorize images in relation to their intended functions. This means that, on the one hand, paintings designed for placement on altars are defined as institutional, public, and liturgical. On the other hand, images designed for private devotion are often defined as being free from institutional constraints or conventions and as being private and non-liturgical, or para-liturgical. In other words, devotional images are defined functionally, in opposition to liturgical images. In fact, this functional opposition is problematic for a number of reasons and is not quite as well defined as has sometimes been suggested. . . . It is likely that there was a much stronger continuum between some aspects of public worship and private devotion than Ringbom’s analysis of the material accoutrements of each variant of prayer might have suggested.9

For these reasons, the present essay will focus on early Netherlandish paintings as devotional objects, that is to say it will focus on the uses of paintings across a range of devotional practices. This implies that the paintings under scrutiny do not need to be “devotional images” as usually understood by scholars (i.e., as defined on strictly formal bases) but could be altarpieces or memorial pieces eliciting specific sorts of devotional responses.10 I agree that the concept of a devotional painting refers to questions of function and viewer response and not to narrow formal or iconographical parameters. I also consider publications dealing with the uses and functions of early Netherlandish paintings in a devotional (or spiritual) perspective and that explore the deployment of these images in the spiritual context of the fifteenth century. The publications under scrutiny move away from treating devotional images as autonomous entities that lend themselves to “internal analysis” (i.e., history of forms and iconography). In place of that analysis, such publications consider these objects in the plurality of their relationships to viewers. All of these publications envision, in one way or another and from various angles, the relationships between paintings as devotional objects and the religious contexts in which they were produced and used by their owners or viewers.11 Thus, I deliberately set aside scholarship dealing with primarily iconographic and stylistic questions, as well as those studying workshop practices related to the production of devotional imagery and to the primarily social or ostentatious use of devotional objects.12

In this respect, my choice to focus on early Netherlandish paintings as devotional objects builds on a turning point our field reached in the study of early Netherlandish religious painting. Julien Chapuis noted that during the second half of the twentieth century, “unravelling disguised symbolism in early Netherlandish painting became the focus of two generations of scholars” who were pursuing a kind of flattened Panofskian method.13 There then emerged criticisms of this approach—in varying degrees of development—that were subsequently followed by works that focused more on how an object functioned and was experienced rather than on what it depicted or “symbolized.”14 Thus, from the late 1980s onward, we find in the literature a greater attention to the contexts for which devotional paintings were produced and in which they were used.

Milestones: From Panofsky to Marrow and Harbison

Panofsky’s “Imago pietatis” is considered a founding text by the scholarly community, as attested to by its frequent citations in later literature. More precisely, this essay has been influential with regard to its focus on the history of motifs and their historical transformations, as well as to its characterization of late medieval devotional images. Like any foundational text, it has also been criticized and revised. Most of these criticisms concern Panofsky’s definition and understanding of the relationship between form and function in the Andachtsbild.15 Notably, Rudolf Berliner argued in 1956 that there is no reason to distinguish the narrative scene from the Andachtsbild. In his opinion, either can function as an object of devotion and an incentive to prayer.16 Hans Aurenhammer similarly pointed out that Panofsky’s definition limits the historical study of devotional images by classifying them primarily on the criteria of specific visual form.17 The debate was then extended by Sixten Ringbom and Hans Belting in works that became touchstones on this issue.18 In his classic Icon to Narrative, Ringbom followed Berliner in asserting that images meeting the iconographic criteria of an Andachtsbild could serve functions that extend beyond supporting devotional engagement. With that in mind, he introduced a slight distinction in terminology: the notion of “devotional image” referred, for him, to the function of the image, while the word “Andachtsbild” concerned the pictorial form (a close-up image of Christ or the Virgin) (see, for instance, fig. 1).19 This nuance was later challenged by Belting, who argued that this distinction is not appropriate, because the interaction between form and function in religious images was not only complex but also reciprocal.20 If Ringbom and Belting criticized some of Panofsky’s arguments regarding the Andachtsbild, they also developed new avenues of research that, in turn, became crucial for the field.21

Panofsky’s argument about viewers’ affective response to the Andachstbild has had a greater and more lasting impact than his observations about form and function. Indeed, Panofsky’s remarks on contemplative immersion have paved the way for a long-lasting and still-frequent appraisal of devotional images as emotional and affective objects aimed at evoking an empathic response in devotees. The success of this appraisal has not been without consequences for our understanding of the uses of devotional images in spiritual practices. As Reindert Falkenburg noted a few years ago:

This subjective and emotional definition of the viewer’s response to the Andachtsbild, while not hostile to the idea that the viewer might contemplate “symbolic” connotations inherent in certain details . . . has consistently pushed not only the discursive (iconographical) content but also the hermeneutic act of recalling and contemplating this content, as well as other concepts of image/viewer response, to the margins of art historical analysis.22

This affective and emotional paradigm has limited our understanding of the uses of devotional images. Nonetheless, as we will see later on, subsequent work opened new avenues of research related to these issues.

James Marrow’s Passion Iconography in Northern European Art, published in 1979, also has been an important touchstone in recent scholarship, despite the fact that it does not offer an analysis of the devotional functions of the images under consideration (contrary to Ringbom and Belting, mentioned above).23 Noting that Christ’s Passion occupies a key position in the religious culture of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, Marrow analyzed the phenomenon of narrative elaboration of Passion imagery in the Low Countries. More precisely, he studied how visual and textual sources transformed Old Testament metaphors into narrative Passion imagery. The major contribution of this study is that it brings together a new textual corpus for the investigation of Passion imagery in the visual arts, namely Middle Dutch treatises. The approach is primarily iconographical but nonetheless also engages with iconology. It does the latter by analyzing text-image relationships and by using textual analysis and literary history to address general questions about the spiritual context of the period.24 Passion Iconography is also clearly situated in the tradition of Panofsky’s emotional and affective approach to late medieval imagery. Marrow stated that even if the late medieval narrative treatment of the Passion follows an older tradition of biblical interpretation, it also attests to the changing spirituality of the period, a spirituality characterized by a more humanized and emotional approach to the divine.

A few years later, Marrow adopted a similar position in his article, “Symbol and Meaning,” in which he criticized scholarly preoccupation with the symbolic dimension of Northern European art of the late Middle Ages, especially in studies that rely heavily on the concept of “disguised symbolism.”25 Offering an alternative, Marrow focused instead on the affective utility of artworks. Building on Panofsky’s notion of contemplative immersion, he argued that Andachtsbilder are “images whose subjects were fashioned to stimulate appropriate emotional responses in viewers” and that many early Netherlandish paintings, such as Van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross (see fig. 3), were fashioned to visualize the type of emotional response that devotees could imitate and cultivate in their personal pious exercises.26 Marrow’s essay is thus particularly representative of its time. On the one hand, it continued the Panofskian tradition of exploring the capacity of images to evoke compassion in the viewers. On the other hand, it also highlighted a shift in perspective that was then taking place. Specifically, Marrow invited his fellow art historians to focus on how art signifies rather than on what it signifies.

In 1985, Craig Harbison published an article that also distanced itself from the iconographical mode of scholarship on early Netherlandish painting. His article became another important resource for later scholars.27 Focusing on the significance of visionary and meditative experiences for the laity in the late Middle Ages, the article explored the role and functions of images in “private devotion.” The result is an important milestone because of Harbison’s willingness to get to the root of “personal and practical piety” as it involved images.28 Thus, the notion of self-identification with saints and visionaries was brought to the fore. Harbison also linked fifteenth-century pictorial production in the Low Countries with late medieval devotional texts, such as Ludolph of Saxony’s Vita Christi (1374) and Pseudo-Bonaventure’s Meditationes vitae Christi (13th century), rather than with scholastic and liturgical sources, as had often been the case in the tradition of decoding “disguised symbolism.” According to Harbison, “the important point was that natural piety and imagination were far more efficacious than learned diatribes.” This is why he stressed “the crucial importance of visions and meditations for Flemish religious life and art,” adding that, in this context, we are dealing with a “methodical meditative process which . . . could produce a kind of visionary experience. If the kind of visions we find in Flemish art are less high-pitched than others, they do still represent a kind of personal mysticism which transcends traditional liturgical piety.”29

It thus appears that by the end of the 1980s, an important shift in the study of early Netherlandish painting had occurred: religious images were increasingly considered devotional objects by virtue of how they were thought to have been used rather than how they appeared. Questions about the functions of devotional imagery, about pictorial rhetoric, and about the responses that rhetoric might provoke in viewers, as well as its relationship to contemporaneous spiritual literature, became core questions for subsequent scholarship dedicated to early Netherlandish painting.

Early Netherlandish Devotional Painting in its Spiritual Context (1990–2020)

By the start of the 1990s, early Netherlandish pictorial production was increasingly being considered with respect to its spiritual contexts. This new era of art historical inquiry was marked by the deployment of a wide variety of research directions and historical methods.30 The resulting scholarship shares two common characteristics: a strong focus on the viewer’s responses and a willingness to consider artworks in terms of reception and use. As a result, visual and devotional experiences now stand at the core of scholarship on devotional images in the medieval and early modern Low Countries.31

In line with Harbison and Marrow, many art historians started to pay close attention to the functions of devotional paintings.32 It was also during this period that investigations of the links between Passion narratives—Hans Memling’s (1430–1494) Simultanbilder, in particular—and spiritual or imaginative pilgrimages started to flourish.33 Similarly, the contextualization of devotional painting has led many scholars to explore how the movement of the Devotio moderna may have influenced, directly or indirectly, early Netherlandish pictorial production and its use in devotional practices.34

The period of 1990–2020 is marked, in my opinion, by two major methodological and theoretical developments. The first concerns text-image relationships, and the second involves increased attention to pictorial rhetoric. The impact of these developments has resulted, over the last thirty years, in a better understanding of the role devotional paintings played in the spiritual life of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. In addition to (or alongside) these methodological developments, it is possible to distinguish two major and intertwined trends in the way early Netherlandish painting has been approached: the first concerns the study of paintings as devotional instruments or tools meant to be used (as opposed to relatively static vehicles for iconographical content), and the second concerns the understanding of images as representations or visualizations of spiritual ideals.

Text-Image Relationships

It is not an exaggeration to state that the broadening of the textual corpora used to analyze early Netherlandish painting, along with the new ways of linking texts and images, was one of the major innovations in the field in the 1990s. This new way of linking devotional texts and images had a strong impact on the research questions addressed by scholars. Published in 1994, Reindert Falkenburg’s The Fruit of Devotion plays a crucial role in this regard, not only for the new type of textual sources it assembles but also because it demonstrates a new way of understanding the relationship between devotional texts and images, one that goes well beyond the traditional iconographical approach.35 Falkenburg had two goals. The first was to study the cultural significance of imagery of fruit and flower consumption in early Netherlandish paintings of the Virgin and Child and associated themes like the Holy Family (fig. 5). Second, he sought to shed light on the devotional functions of these images. To do so, he brought forth a corpus of contemporary devotional treatises written in the vernacular and largely distributed in manuscripts and small printed editions, which he discusses in close connection with his chosen paintings.36 Crucially, Falkenburg is interested less in tracing iconographical details than in demonstrating the spiritual utility of activating the senses by appealing to sight.

Since Falkenburg’s approach strongly shaped further scholarship in the field, it is worth paying close attention to his methodological statements. Falkenburg does not consider contemporaneous texts as “immediate key[s] to the meaning of the consumption motif” in the paintings of the Virgin and Child.

I do not think that the meaning of pictorial metaphors in late medieval Andachtsbilder can be revealed by simply pointing to a certain text. What I do wish to show is that the consumption motif in late medieval devotional painting has certain semantic value which ultimately derives from the love imagery of the Song of Songs, but are part of a polysemic devotional imagery that was widespread in the late Middle Ages and took variety of expressions.37

At the end of his study, Falkenburg clarifies his view:

One should be careful not to stretch the parallels between the genres too far. . . . The literary garden allegories cannot be considered to be the direct inspiration for the paintings. . . . [They] seem to diverge on a number of essential points. . . . This is what appears to be the case from a purely iconographic study of these paintings. Yet when one takes into account the religious function these paintings had and analyzes the form and impact of the devotional image on its invisible counterpart—the viewer—it is possible to identify a convergence between Andachtsbilder and devotional texts.38

Building critically on the works of Ringbom and Panofsky, Falkenburg renewed the study of the functions of devotional imagery by proposing an innovative and culturally informed approach to the relationship between devotional texts and images.39 Also important is his focus on the notion of the inner self and the reformation of the soul, as we will see later.

A few years after the publication of Falkenburg’s The Fruit of Devotion, Bret Rothstein published an article on Jan van Eyck’s Van der Paele Madonna (see fig. 2), followed by a book titled Sight and Spirituality in Early Netherlandish Painting (1999 and 2005, respectively).40 These publications further advanced the study of devotional imagery in dialogue with spiritual literature.41 Defining the act of seeing as a culturally grounded practice, Rothstein examines the relationship between late medieval images and devotion, not so much from the perspective of function but rather from the point of view of visual culture and the role of vision in devotional experience.42 To my knowledge, his works are the first attempt to study early Netherlandish paintings in light of contemporary mystical literature—more precisely, the works of Jan van Ruusbroec (1293–1381), Jean Gerson (1363–1429), and Geert Grote (1340–1384). Rothstein carefully justifies his choices: he examines these texts less because of their status as mystical literature than because they address the spiritual ramifications of vision, which occupies a key position in late medieval thinking. More specifically, Rothstein chooses to focus on texts written in the vernacular because they have a higher probability of representing “the sort of knowledge available to . . . painters, patrons and viewers.”43 In addition, and like Falkenburg, Rothstein treats “primary texts as counterparts or analogs rather than sources.” He explains: “While they and the paintings at hand evince a number of common interests, the pictures necessarily articulate those interests in fundamentally different ways and viewers apprehend them in correspondingly different fashion.”44

In the spirit of Falkenburg and Rothstein, art historians from the 2000s onward have more frequently utilized spiritual literature to illuminate the functions and/or meanings of early Netherlandish devotional paintings. John Decker, for instance, explores how Geertgen tot Sint Jans’s (1465–1495) paintings, such as his Man of Sorrows now at the Catharijneconvent in Utrecht (fig. 6), constitute a “technology of salvation” by referencing religious texts that were “well known or had fairly broad distribution in the fifteenth century,”45 such as the writings of the fathers and doctors of the church or authors like Ludolph of Saxony and Gerard Zerbolt van Zutphen (1367–1398).46 Similarly, I have analyzed the visual strategies of devotional portrait paintings in close relationship with concepts and metaphors derived from contemporary Dutch and Latin spiritual literature (such as treatises by Zerbolt, Ruusbroec, Florent Radewijns (1350–1400), and Grote).47

It is worth noting here that art historians bring different perspectives to the same texts. If the aforementioned scholarly works use mystical and devotional literature as a distinct but complementary way to understand the place of imagery in spiritual practices, other publications invoke these same texts to grasp the meaning and symbolic significance of paintings. This trend of visual exegesis is notably illustrated in several essays published by Elliott Wise, as well as by “non-art historians” like Edward Bekaert and Geert Warnar, who also convoked writings by Ruusbroec, or Inigo Bocken, Harald Schwaetzer, and Wolfgang Christian Schneider, who draw on the work of Nicolaus Cusanus (1401–1464).48

Finally, although it has been predominant, spiritual literature has not been the only textual source used in recent work on devotional paintings. Other studies have relied on theater, liturgical dramas, and rederijkers’ literary productions in their analyses.49 Still, it is striking that art historians have rarely studied texts of prayers in an extensive way in dialogue with early Netherlandish painting. This makes for a stark contrast with manuscript studies, discussed below. One notable exception is an article by Bernadette Kramer on the Virgin and Child with a Woman in Prayer by the Master of the View of Sainte-Gudule (fig. 7), which analyzes rosary prayers to argue that this painting evinces the success of fifteenth-century Flemish rosary devotion.50 Another is Miyako Sugiyama’s book on the relationships between indulgences and early Netherlandish paintings.51

Pictorial Rhetoric

The richness and complexity of visual strategies developed by painters to produce meaning or prompt viewer responses are also at the core of recent scholarship. From the 1990s onward, art historians have been increasingly eager to depart from the traditional iconographical approach and theories of disguised symbolism. These scholars started to pay increasingly close attention to the languages of images, especially the pictorial rhetoric of paintings, by producing studies jointly analyzing iconographic motifs as well as formal and compositional elements.

The result has been a growing research focus on visual strategies—such as pictorial devices and spaces, boundaries, thresholds, and visual complexity (or even difficulties)—as means to convey meaning and to shape the spiritual experience of their beholders. Indeed, several publications have focused on early Netherlandish painters’ visual strategies to shape viewers’ responses and interpretations.52 In a 1998 article on pictorial time in the Saint Columba Altarpiece (fig. 8), Alfred Acres states that Rogier van der Weyden’s work is “a matter less of symbolism than of representational rhetoric—in the sense of depiction that is carefully calculated to explain and persuade” and that it is “distinctive for articulating thematically loaded relationships both among certain contextual elements within the image and between these elements and the viewer.”53 He then compares this “structure of thought” to exegesis before analyzing a whole series of visual devices in the work. A similar approach to visual exegesis can also be found more recently in publications by Elliott Wise, which are also largely devoted to Van der Weyden’s oeuvre.54 How devotional paintings, through their pictorial devices and strategies, shape and influence the beholder’s spiritual experience is also a focal point of publications by Vida J. Hull (on Memling’s Passion narratives), Peter Parshall (on Hieronymous Bosch’s Mocking of Christ) and Lynn Jacobs (on the format of the triptych).55

Likewise, in the last decade or so, several studies have explored how early Netherlandish paintings visualize important issues related to spiritual and perceptual experiences: in the introductory part of Die Erfindung des Gemäldes, co-written with Christiane Kruse, Hans Belting explores how, in the fifteenth century, the Netherlandish tableau contributed to a “painted anthropology of the gaze” (eine gemalte Anthropologie des Blicks)—in other words, how vision and the gaze are thematized in early Netherlandish painting.56 Bret Rothstein analyzes in his publications mentioned above how the Van der Paele Madonna conveys an ideal of aniconic meditation, as embodied and visualized in the figure of Canon Van der Paele.57 Martin Büchsel shows how Van Eyck’s Madonna in a Church formulates penitence and redemption through the use of iconographic motifs and compositional strategies such as the double viewpoint (fig. 9).58 And, by confronting the representational rhetoric of Van Eyck’s Rolin Madonna and Van der Weyden’s Saint Luke painting the Virgin (fig. 10), Alfred Acres argued that both images thematize the act of seeing and its implications.59

In the study of later medieval and early modern art, the beginning of the 2000s was characterized by a new interest in questions relating to pictorial space, its representation, and its construction. As Jean-Claude Schmitt notes in his influential book Le corps des images: Essais sur la culture visuelle au Moyen Âge (The Body of Images: Essays on the Visual Culture of the Middle Ages), “the spatial construction of the image and the arrangement of the figures are never neutral: they simultaneously express and generate a categorization of values, hierarchies and ideological choices.”60 This trend of research can be observed in our field. With respect to paintings that include devotional portraits, I have explored the structuring and the nature of the pictorial space, which frequently implies a subtle interplay of differentiation, gradation, or fusion between the secular and sacred zones of the composition.61 Alfred Acres analyzes the charged articulation of foreground and background of painting; he pays particular attention to “distant figures”; that is, “figures placed in the background that attest to a little-noted tendency among certain early Netherlandish painters to insinuate things and places to which the viewer’s access is radically and often tantalizingly limited.”62 Thresholds and boundaries between the different parts of the work, particularly the shutters and the central panels of triptychs, have been studied to powerful effect by Lynn Jacobs, who has argued for the “construction of meaning” of the triptych format.63

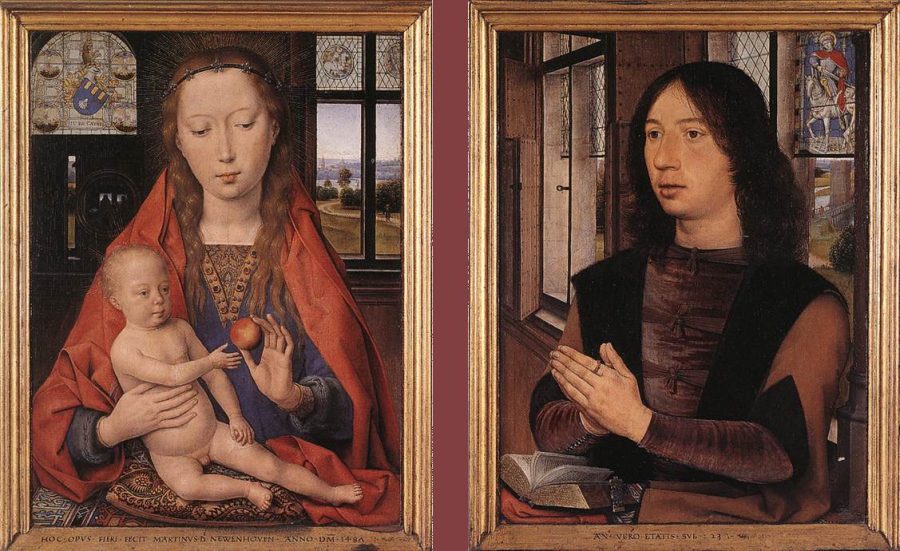

Finally, several recent works highlight the visual complexity of early Netherlandish devotional imagery and how it engages beholders in a viewing and meditating process. According to Falkenburg, visual ambivalences are a “structural (structural also in the sense of positive, constructive) component of the late medieval Andachtsbild,”64 while Acres argues that many paintings seem to be “designed more to solicit reflection than simply to affirm fixed tenets.”65Among the pictorial devices of these images, spatial and compositional ambiguities play an important role. In this respect, Memling’s works—notably the Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove (fig. 11)—have loomed especially large in the scholarship because of the painter’s facility with and taste for reflections, visual ambiguities, and other compositional complexities.66 Similarly, in his essay on Hieronymus Bosch’s (ca. 1450–1516) Mocking of Christ (fig. 12), Peter Parshall shows that the depicted actions and ambiguous attitudes of Christ’s antagonists derive “from a conscious decision on Bosch’s part to lay a trap” and that the complex deployment of motifs “alerts us that he [Bosch] is playing a sophisticated game of contradiction.”

These works attest to continuing scholarly reflection on the concept of “indeterminacy” (defined by Dario Gamboni as “the character of something undefined, unestablished, not precisely outlined”67) and its variants, “ambiguity” (the quality of being open to several interpretations) and “ambivalence” (having two or more opposing interpretive possibilities), in all registers of late medieval and early modern Netherlandish visual culture.68 This line of scholarly inquiry still has its best days ahead.

Paintings as Devotional Instruments

The dominant approach in recent decades has undoubtedly been to consider devotional paintings as supports for the spiritual praxis of their owners or viewers. In the early 1990s, there was an emphasis on the exemplary dimension of these images—that is, their capacity to model an ideal practice or behavior. As is now well known, in late medieval devotional culture, devotees were constantly invited to empathize and identify with the sacred personae, and art historians have demonstrated that religious images were used in the process of imitation, with saintly figures providing examples of behaviors that viewers could adopt.69

One early example of this approach is Falkenburg’s article “The Household of the Soul,” dedicated to Robert Campin’s Mérode Triptych (fig. 13). Falkenburg argues that a “technology of inwardness” characterizes fifteenth-century devotional culture, in which “both text and image serve as instruments of spiritual self-constitution through meditation and inner visualization.”70 In this essay, Falkenburg introduces a conceptual model that has had a tremendous impact on later scholarship: the devotional image as an tool for the reformation of the soul. According to Falkenburg, the center panel of the Mérode Triptych alludes to the metaphor of the “house of the soul,” an analogy popular in contemporaneous devotional texts inviting devotees to imagine their souls as a house to furnish with objects corresponding to virtues.71 The center panel can be understood as a visualization of this metaphor: the Virgin welcomes Christ in her heart at the Annunciation and therefore serves as a frame of reference for devotees, who must imitate her in order to fashion the house of their souls and welcome God as well. To describe this process, Falkenburg draws on the notion of “conformity” (conformitas; medevormigheit), which consists of the repeated use of the same metaphor (e.g., the soul as house), first applied to the Virgin and then to the devotee. In Falkenburg’s argument, that repetition helps the postlapsarian soul reform itself by recognizing commonalities between the mundane and the heavenly. Devotees must conform themselves to the Virgin, who is presented as an exemplary model. According to Falkenburg, the triptych therefore suggests that the devotees’ prayers will enable them to penetrate spiritually into the room of the Annunciation, to consider the space as their own, and finally to reform their souls.

The idea of paintings as tools for self-reform has since been utilized by several other scholars in recent decades. This is notable in the case of John Decker and Henry Luttikhuizen, who, respectively, interpret devotional paintings by Geertgen tot Sint Jans and the Master of the Spes Nostra as instruments for structuring viewers’ meditation and, thereby, reforming their souls.72 This latter concept is key in late medieval and early modern meditative theory and practice. As Walter Melion has explained, meditation was conceived of “as the spiritual process whereby pictures are taken in by the eyes and then taken up by the soul, wherein they are imprinted and transformed. This exercise is itself transformative, for it aims to effect a turning of the soul toward God, or better, a restoration of the soul as imago Dei, made in the true image and likeness of its Creator.”73 Such a definition could also be briefly summarized by saying, as Jeffrey Hamburger does, that meditation is “a process of internalization, of conforming oneself to Christ.”74

The notions of “meditation” and “reformation of the soul” have transformed how we conceptualize and discuss the use of images as spiritual instruments. In 2007, the authors of a volume edited by Melion, Falkenburg, and Todd Richardson interrogated the relationship between images and meditation by means of case studies that extend well beyond fifteenth-century Netherlandish painting. The introduction to the volume states that their goal is to explore “how and why pious men and women manipulated, or better, cultivated their souls by means of religious images.”75 Following subsequent colloquia, two further edited volumes came out, as did several related essays and monographs.76 These works consider devotional paintings in their capacity to serve as “instruments,” “tools,” and “devices,” and it is interesting to note that the adoption of these terms has replaced a previously recurrent phrase, “support for prayer.”

As this scholarly trend shows, meditation implies prolonged work by the devotee, work in which the image structures and guides spiritual practices. A case in point would be Mitchell Merback’s essay on the Man of Sorrows (see fig. 6), which proposes approaching these images as Meditationsbilder rather than Andachtsbilder:

Under the Andachstbild paradigm, the image of Christ in Repose functions as a vehicle for compassionate identification, contemplation of the Passion’s mysteries, and eventually a catharsis of the religious ego—steps along the mystic’s vertical path toward the visio dei, toward the soul’s union with the divine. Under what I am calling the Meditationsbild model, the image of Christ’s melancholy distress appears by contrast as a speculative reflection of the soul’s inner strife and an instrument for its restoration and repair.77

Paintings as Visualizations of Spiritual Ideals and of the Contemplative Process

In parallel to the exploration of early Netherlandish paintings as instruments of devotion and/or meditation, scholars have also been concerned with showing how these images were invested with a capacity to visualize and thematize the spiritual experience of their viewers. While this line of research may be somewhat less extensive than the one discussed above, it nevertheless testifies to a stimulating and generative line of inquiry that has developed in the last several years. This line expands on the investigation of images as tools; it also relies on other trends of research in visual studies, notably research into the performativity and agency of images.78 The issue of what a painting can do for viewers, or how it can act on them, is at the core of this scholarship.

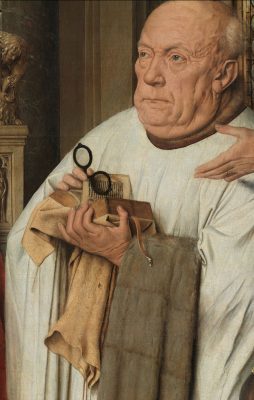

The first attempt at understanding how a devotional painting can visualize a state of spiritual perfection was Harbison’s aforementioned article on vision and meditation in fifteenth-century Flemish paintings. As Harbison explains, his goal is to “show how artists found the means to visualize, subtly and fully, the chief religious ideal of the time, lay visions and meditations.”79 He argues that the canon in Van Eyck’s Van der Paele Madonna is depicted immersed in his own meditation, having a mental vision of the Virgin (fig. 14). Interestingly, this painting has prompted several art historians to query how a painting can visually express a spiritual ideal. Indeed, twenty years after Harbison’s article, Büchsel and Rothstein extrapolated on his argument in order to deliver their own interpretations of this landmark painting alongside other objects. According to Büchsel, the depiction of the canon, holding an open book and his glasses in his hands (Fig. 14), “is surprising for its precise definition of the act of devotion. . . . He moves from lectio to meditatio and thereby to visio. This widespread basic scheme of devotion opens up the transformation of instruments of devotion into the image of their fulfilment.”80 Likewise, he argues that, due to several pictorial strategies in the Madonna in a Church, Van Eyck transforms the traditional subject of the Virgin and Child into an image of the meditational process (see fig. 9).81 Utilizing another methodological approach, Rothstein claims that the Van der Paele Madonna thematizes the ideal aniconic state of meditation and thus invites the viewers to cultivate this state of spiritual perfection.82

Details and background elements of paintings have also been studied as ways to thematize spiritual vision. This approach is notable in Inigo Bocken’s research on the paintings of Jan van Eyck, specifically the depiction of background viewers, such as those in Van Eyck’s Rollin Madonna (figs. 15 and 16), whom he links to Cusanus’s work on the visio Dei as a form of visual thinking.83 Research dedicated to Simultanbilder and imaginative pilgrimages also approaches images as visualizations in devotional practices.84 For instance, Sally Whitman Coleman, building on Umberto Eco and Paul Ricoeur’s models of narratology, has argued that the complexity of Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ (fig. 17) helped worshippers experience the revelations of Christ in conjunction with the liturgy of the four major Church festivals.85 Finally, in my own research I hypothesize that numerous early Netherlandish paintings with devotional portraits can be considered as mises en image of the spiritual progression of sitters or, in some cases, even as the complex outcome of that progression.

Research Perspectives

In assembling and reviewing this panorama of research on early Netherlandish paintings as devotional objects from the last thirty years, one thing is clear: whatever the focus of research, the place of the viewer, or their interactions with the image, what they project onto the image and what they derive from the image all lie at the center of art historians’ attention. Viewers’ engagements—hermeneutic, sensory, emotional, etc.—with this imagery is a frequent avenue of inquiry.86 The results are among the major scholarly contributions of the last thirty years: (re)thinking the relationship between viewer and image by developing new approaches; rethinking how we use (religious) texts to recover the more elusive historical uses and meanings of these paintings; and using new sources, both visual and textual, to sharpen our perception of what uses, and thus meanings, might have been possible in the first place. The last three decades have been especially fruitful in this respect, having largely renewed the field.

This does not mean, however, that all is known and understood. On the contrary, early Netherlandish devotional paintings’ complexity and richness (both semantic and formal), in connection with other aspects of the spiritual culture of the time, including the diversity of viewers’ gazes, invite us to continually renew our approaches and ask new questions. As a way to conclude this essay, I therefore propose a few lines for further inquiry.

Recent research has shown that devotional paintings were integral to a broader cultural phenomenon, namely lived spiritual experience. Consequently, it is important to recognize that image-based meditation and devotion were thoroughly entangled with other cultural practices and, thus, other objects, as well as senses beyond just sight. This entanglement needs to be more fully addressed by scholars who study devotional images and are willing to reconstruct (or, rather, better understand) the fuller experience of using devotional images. We need to pursue intermediality and consider the material culture of spiritual practices. The “material turn” observed in the humanities in recent years allows us to approach devotional practices as embodied, in the fullest sense of that term.87 We also would do well to engage with another recent development in medieval studies, namely the study of the sensorium (both physical, or external, and spiritual, or inward) in devotional experience.88 Likewise, the link between liturgy and devotional images could benefit from further exploration, as suggested by Beth Williamson.89 As mentioned above, the relationship between paintings and prayers also deserves special attention, not only with respect to the phenomenon of indulgences but also with attention to the texts of specific prayers that could be associated with paintings. In several cases, this dialogue with recited prayers is made obvious in the artwork itself. Two notable examples include the Triptych of the Virgin and Child, a painting by a late fifteenth-century anonymous master that includes the Salve regina prayer on its wings (fig. 18),90 and a privately held Triptych with the Holy Face that is inscribed with the Salve sancta facies indulgence prayer on the wings.91 But many other early Netherlandish paintings without such inscriptions could be explored in relation to prayer practices. Indeed, if the notions of “devotion” and “meditation” are now well associated with early Netherlandish paintings, it is striking that the concept of “prayer” has been largely untouched by art historians, in contrast to what is observed in manuscript studies. In this respect, Kathryn Rudy’s work, especially her study of prayer books and indulgences, reveals stimulating research opportunities to renew our approach to early Netherlandish devotional paintings. As she observes, “prescriptions in prayer books reveal aspects of the function and reception of devotional images in the fifteenth century.”

Late medieval devotional imagery has been almost exclusively considered from the perspective of affective piety and emotional response since Panofsky’s foundational work. While it is true that later works focusing on the notion of spiritual vision and meditation have moved the field toward a somewhat more complex and subtle approach regarding the role of images in spiritual experience, the fact remains that this “affective paradigm” is still predominant. Likewise, and perhaps more important, we still have a narrow understanding of affect as it was understood in the late Middle Ages.92 Yet textual sources, if read carefully and subtly, indicate that images served far more complex functions than simply stimulating devotion and eliciting emotional responses. Texts such as those by Suso (1295–1366) or Cusanus point toward the capacity of images to produce knowledge and trigger intellectual processes in the spiritual realm. A few years ago, Rothstein questioned the ways art historians usually understand the relationship between empathic and intellectual responses to the image: “The affective image, it would . . . seem, is little more than a shoddy conduit through which faith may travel, because its viewer is concerned only with the state of her or his soul.” He goes on:

The preconceptions governing this model haunt much of the literature, both historical and contemporary, on the subject of emotional responses to devotional art. At the heart of the matter lies a distinction between pictures governed by and supposedly appealing to reason, on the one hand, and those supposedly governed by affect and dedicated to provoking the copious flow of lachrymal fluid, on the other hand. It is as if empathic and intellectual responses to the image are mutually exclusive, as if depth of feeling equals shallowness of thought.93

Recent scholarship thus tends to acknowledge the cognitive power of devotional images and attests to the need to better explore the full scope of the emotional response they inspire.

Finally, art historians should give more consideration to the terminology we use when addressing religious imagery and the practices with which it entangled. What are—or, more precisely, what were—fifteenth-century Netherlandish devotion, prayer, meditation, and contemplation? And, based on those questions, how might art historians define a pious, devotional, or meditative image? Can we distinguish one type of image from another one with any real confidence? Reading this vast scholarship and working on primary sources leads to the observation that our categories of analysis are probably too strict or rigid and that they therefore flatten a late medieval spiritual landscape that is more complex than we might otherwise realize. We need to carefully reconsider and redefine these concepts and terms while also acknowledging that, although helpful, such concepts and terms actually restrict our understanding of how these images were used. In this regard, I wonder if it might be better to think and speak about types of uses and responses to imagery rather than types of images, because the latter are categories determined by art historians and thus, by definition, anachronistic. One single image could be used in various contexts and by people with different levels of intellectual sophistication and affective capability. In other words, terminological work is still necessary, but this should perhaps concern cultural practices rather than pictorial genres.

One last word. In the past few decades, scholars have proposed new ways of interpreting devotional imagery. As Andrea Pearson writes, “this is risky business in the study of early Netherlandish painting, where arguments supported by direct evidence, preferably textual, technical, or material, are traditionally favored and in which only a handful of dedicated studies on the subjectivities of looking and seeing have appearing.”94 If interpreting the uses and meanings of these images is indeed a risky business, it is also a necessary and stimulating one. By freeing ourselves from the too-strict categories that helped found our field, we can free ourselves to sense more finely the cultural and visual environment of the fifteenth-century Low Countries. In recent years, we have witnessed the development of more complex and nuanced approaches to paintings (and, more generally, images) that shaped spiritual experiences, structured them, and made them visible. These approaches might sometimes seem “speculative,” but they offer a fuller consideration of the diversity of viewers’ gazes and the functions of imagery while enabling us to get at the core of early Netherlandish spirituality. What we, as art historians, need to do now is to think across media and across practices by acknowledging the various levels of sophistication of spiritual experiences in the fifteenth-century Low Countries.