For a brief moment in the early sixteenth-century Low Countries, etching became a significant technique for elite commissions. I examine the two earliest etchings made in the Low Countries as a case study: the portrait of Maximilian I by Lucas van Leyden and the portrait of Charles V by Jan Gossart, both made for the Hapsburg-Burgundian court in 1520. The etching technique was integral to the success of the two portrait prints, for both artists as well as their patron. This is a localized instance of artistic emulation and competition within the emergence of a new technique and subject: the Netherlandish portrait print.

Introduction

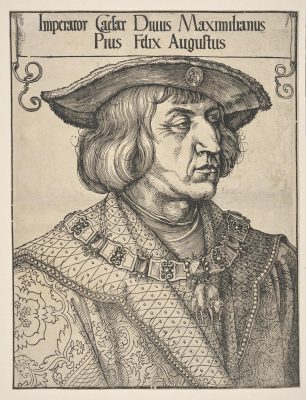

The earliest etchings from the Low Countries are imperial portraits: one a depiction of the recently deceased Maximilian I by Lucas van Leyden (ca. 1494–1533) and the other a depiction of his successor, Charles V, by Jan Gossart (ca. 1479–1532) (figs. 1 and 2). The two prints share approximate dimensions as well as the date of 1520, and each is signed with the artist’s monogram. They are also strikingly similar in their formats and in the treatments of their respective sitters. We know that Philip of Burgundy (1464–1524), the bastard son of Philip the Good, commissioned the portrait of Charles V (1500–1558) from Gossart, and circumstantial evidence suggests that he also commissioned Lucas’s portrait of Maximilian I (1459–1519). Philip of Burgundy was indebted to Maximilian I for advancing his political career, a fact that may have motivated him to commission the prints, insofar as paying tribute to the two emperors would allow Philip to assert his own political authority.

Lucas and Gossart created novel printed portraits suitable for an esteemed audience by simulating the visual properties of oil paintings. Both artists also emulated imperial woodcut portraits by German printmakers yet simultaneously transformed these sources to invent a new kind of portrait print, one more relevant to a local, elite milieu. In particular, the prints depict the Holy Roman emperors with a striking verisimilitude that recalls fifteenth-century Burgundian painted portraits. In this respect, the prints belong to a larger revival of the art of Jan van Eyck (1391–1441) in the early sixteenth-century Low Countries, partly meant to assert Hapsburg-Burgundian independence during an important transition of power.1

The imperial portraits are remarkable achievements, both technically and stylistically. In his 1604 biography of Lucas van Leyden, Karel van Mander praised Lucas’s Maximilian I as his finest print.2 For its part, Gossart’s Charles V is one of the most accomplished iron etchings of its time. Unlike contemporary German woodcut portraits, both of these etchings take visual likeness as an artistic aim; the sitters are articulated in space and engage with the beholder—and, as discussed below, perhaps even each other.

The two printed portraits point to a localized instance of artistic emulation and competition within the emergence of a new technique and subject: the Netherlandish portrait etching. This article argues that the newness of etching, in conjunction with each print’s interpictorial resonances, was integral to the success of the two portraits for both artists and patron. Specifically, it contends that the innovative technique and stylistic allusions of the prints would have enjoyed prestige in courtly circles. The motivation for this argument lies in a strange quirk of the secondary literature. The Hapsburg-Burgundian court was an important catalyst for the development of elite print projects in the first three decades of the sixteenth century, yet this context of the commission has not received due scholarly attention. In a partial effort to address that lack, this article concludes by examining the broader courtly impetus for supporting early etching.

Jan Gossart, an esteemed court artist known for his painted portraits of nobility and mythological subjects, created only four or five prints. This tally includes two etchings on iron: the portrait of Charles V, which survives in a unique impression with later hand-coloring in Braunschweig, and The Mocking of Christ of about 1525.3 Lucas van Leyden, by contrast, worked primarily for urban audiences in his hometown of Leiden, achieving international renown more for his engravings, which circulated across Europe, than for his paintings. He engaged with etching briefly in 1520, when he produced six copper plates, including the portrait of Maximilian I. Lucas did not work at a court, and his success with printmaking freed him from more traditional patterns of patronage. That his sole portrait print may have been a commission from a high-ranking member of the nobility is significant because it signals that Lucas nonetheless enjoyed contact with an important circle of patrons and court artists. Lucas was an established printmaker with an international reputation by 1520, and he may have been seeking a new audience in order to adapt and elevate his prints for elite audiences.4

The early history of etching in Europe is not well documented. No records survive of the invention and spread of the technique, and we have only fragmentary documentary evidence about its earliest practitioners. Consequently, only the early prints themselves offer clues about the early history of the medium. Lucas was apparently the first European artist to combine etching with engraving on a copper plate, a hybrid technique he seems to have first employed in 1520.5 Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and his contemporaries in the German-speaking lands were etching on iron plates around 1515–1518, and the first Italian artist to make etchings was Parmigianino (1503–1540) in the late 1520s.6 How these developments came about is a vexing question. Technical knowledge and access to materials would have been important factors.7 Copper plates require a different mordant (or corrosive solution) than iron plates: the solution for etching on iron is a product of salt diluted in strong vinegar (both relatively readily available in sixteenth-century northern Europe), whereas etching on copper required nitric acid, which was difficult to acquire at the time.8

It is logical that Lucas would have taken up etching on copper, since he used copper plates for his engravings, but there is no satisfactory explanation for how he learned of copper mordant. Van Mander wrote that Lucas had learned printmaking from an armorer who worked with etching.9 However, another avenue seems more likely. Since armor decoration was exclusively on iron, it is unlikely that Lucas would have arrived at etching on copper in that context.10 Lucas did travel throughout the Low Countries, though, and he was in contact with Dürer, Gossart, and others. These meetings are recorded as taking place only after 1520;11 nonetheless, by that date Lucas was something of a touchstone for high-profile artists, leading one to suspect that another, earlier visiting foreigner to Leiden may have played a role in sparking Lucas’s interest in etching.

The Portrait Prints

The posthumous portrait of Maximilian I was made shortly after the emperor’s death on January 12, 1519. Lucas based his design on Dürer’s woodcut portrait of Maximilian, which the etching follows in reverse. While Dürer’s portrait was the source of inspiration, Lucas made so many important changes and added so many embellishments that he effectively created a new type of portrait print. Through a complex technique that combines etching and engraving, he achieved a level of detail and a mimetic quality unprecedented in portrait prints at that time. In this respect, the detailed physiognomy and meticulous rendering of surface textures in Lucas’s portrait anticipate characteristics for which Dürer’s engraved portraits became renowned several years later. One thinks, for example, of the latter’s depictions of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenberg (1523) and of Philip Melanchthon (1526).

For his portrait of Maximilian, Dürer drew the emperor from life using black chalk or charcoal augmented with red and white chalk (fig. 3). The resulting image dates from when the emperor and the artist met at the Imperial Diet in Augsburg on June 28, 1518, as recorded in an accompanying inscription. His woodcut portrait as well as two painted versions were made shortly thereafter, deriving from the incised drawing. After Maximilian’s death, Dürer’s undated woodcut portrait (fig. 4) appeared in at least four editions by January 1519. It was disseminated widely across the Holy Roman Empire and quickly became the representative image of the emperor.12 In Dürer’s portraits, Maximilian’s profile is framed by a scroll with a commemorative inscription, against a white background. Lacking any suggestion of spatial or narrative context, the woodcut portrait takes on an iconic quality.

In his etching of the emperor, Lucas emulated Dürer, who by the time of the print’s execution had become renowned for imitating nature and who had drawn Maximilian from life. However, Lucas transformed his model by elaborating the sitter’s pose, adding self-consciously playful details, and updating the architectural background in line with regional trends in Netherlandish portraiture as well as a burgeoning interest in the antique style in northern Europe. In Lucas’s print, the emperor is shown on a balcony, resting his left hand on a balustrade, which is adorned with a tapestry bearing the Hapsburg double eagle, and holding a small scroll in his right hand. A landscape is visible in the distance, seen through one half of an arch, which is reminiscent of the background in Dürer’s engraving The Small Horse (1505).

In a departure from Dürer’s prototype, Maximilian’s arms and hands look somewhat awkward and are too small for his body. Far from being a stylistic or technical error, this departure was purposeful, allowing Lucas to make an important historical reference. The motif of one hand holding an attribute and the other hand resting on a ledge can be traced back to Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1400–1464), seen for example in his portrait of Charles the Bold (ca. 1461–1462; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie). This motif was enjoying a resurgence of popularity in early sixteenth-century portraiture; an important example by an unknown Netherlandish artist is the portrait of Henry VII of England from 1505, shown with his hands resting on a fictive parapet holding a rose and wearing the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece (fig. 5). Joos van Cleve (1485–1541) also employed this motif in his portraits of Maximilian (fig. 6).13 In the first quarter of the sixteenth century, he and artists such as Quinten Massys (1465/6–1530), Bernard van Orley (ca. 1491/2–1541), and Gossart created painted portraits that combined fifteenth-century naturalism with new dynamism and witty trompe l’oeil effects.14

In portraying Maximilian I, Lucas combined etching and engraving in an innovative and experimental way. For instance, he coordinated the two techniques to depict contrasting and meticulous surface textures. The clothing, hat, and background are etched; the hair and face of the sitter are engraved; and the hands are etched and reinforced with a burin. The surviving preparatory drawing (fig. 7) indicates that Lucas carefully planned this complex coordination, as first noted by Karel Boon: the lines that would be engraved (the face and hands of the emperor) are drawn precisely, whereas the etched areas of the print (the background, hat, and tapestry) are much more fluid in execution.15 The preparatory drawing for Lucas’s portrait of Maximilian gives significant insight into his working process and suggests that Lucas was keenly aware of the effects offered by these different intaglio techniques.16

Lucas’s combination of engraving with etching has traditionally been interpreted as evidence of unease with the new technique, and his reliance on engraving for areas of significance (e.g., the face) has been cited as further evidence of a lack of confidence.17 This interpretation, however, presupposes that “pure” etching was the goal, with that notion of purity driven by modern criteria. A similar attitude is evident in the changing reception of Rembrandt’s etchings.18 A. M. Hind considered only states of pure etching to be truly excellent, and this viewpoint remained influential in subsequent accounts of the artist’s prints.19 However, in 1520, the combination of etching with engraving brought a new technology into contact with an established practice, a development that would much more likely have been seen as innovative rather than corrupting at the time, especially given the elite context in which that combination came about. Such innovation brought distinct benefits, too, since it allowed artists to bring a painterly tone to linear depiction. Etched passages mimic fine strands of hair, fur, and threads, while tapered, engraved lines suggest a crisper modeling of light, seen prominently on the cheekbones and nose of Maximilian.

In his portrait of Maximilian, Lucas also combined older traditions of portraiture with a new, dynamic approach. He added playful elements to his portrait that wittily break the illusionism of the meticulously rendered scene: two half-naked fools grasp hands and attempt to scale or dance around the column to the right of the emperor, and a third fool holds up a plaque with the date and the artist’s monogram while standing atop a dead deer lying supine—which provides a striking visual parallel to the prominent Golden Fleece pendant around the emperor’s neck. Such architectural ornamentation features prominently in Dürer’s designs for the emperor—for example, the putti, harpies, vegetal ornament, and grotesques that adorn the structure of his Triumphal Arch (1515)—but in Lucas’s print, the figures appear to be playfully animated and break free from the architecture. By incorporating these motifs into his composition, Lucas recasts Dürer’s image of the emperor into the current Netherlandish artistic mode while also rivaling the verisimilitude of surface textures that characterized local artistic tradition.

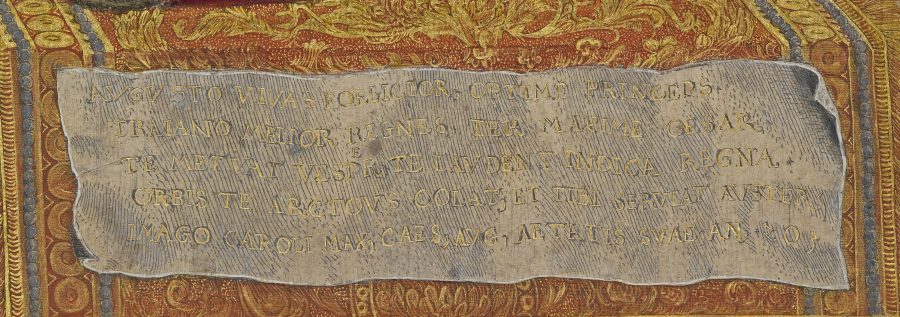

It is known that Philip of Burgundy commissioned Gossart’s print, but it is less clear how this portrait of Charles was produced: in contrast with Lucas’s portrait, there is no surviving preparatory drawing by Gossart. Gossart had access to Netherlandish nobility through his role as court painter. He had met Charles at the court of Adolph of Burgundy around 1517, and he could have met him again when Charles returned to the Netherlands between 1520 and 1522. However, we should not assume that the portrait was made from life, for Charles’s features are markedly similar to earlier German woodcut portraits. Indeed, Charles looks young in Gossart’s print, possibly younger than the age noted in the Latin inscription on the print, “ . . . IMAGO CAROLI MAX, CAES, AVG AETATIS SVAE. AN 20 3” (twenty years and three months).20 By the time of the print’s execution, Charles had already been elected (on June 28, 1519) but not yet crowned Holy Roman Emperor, which would take place later that year on October 23/24, 1520. As Nadine Orenstein has observed, Charles’s boyish features resemble the many woodcut portraits of him made between 1515 (when he came of age and assumed control of the Netherlands) and 1520 (when has was crowned Holy Roman Emperor).21 Several German woodcuts depict the young Charles with a physiognomy and costume similar to those in Gossart’s portrait. Two cases in point are the woodcut published in Augsburg by Jost de Negker and attributed to Hans Weiditz (ca. 1495–1537) (fig. 8) and Hans Baldung’s (1484/5–1545) illustration to Hieronymus Gebweiler’s Libertas Germinae, both from 1519.22 It seems likely that Gossart based his portrait on these earlier woodcuts.23 Gossart’s highly finished drawing of Christian II of Denmark (fig. 9), made from life and intended for another portrait print that the artist did not complete, gives a sense of how Gossart drew his sitters from life: through short, careful strokes, he modeled volume and rendered the physiognomy, costume, and ornament with precise detail.24

Gossart’s portrait of Charles V survives in only one impression today, in Braunschweig, as part of a collection of portrait prints of popes, emperors, and rulers kept together since at least the seventeenth century. This collection of prints was colored by hand in the second half of the seventeenth century by Dirck Jansz. van Santen (1637/8–1708), and this later alteration of the single surviving impression presents a challenge to the study of Gossart’s important portrait print.25 Nonetheless, we can arrive at a few tentative conclusions.

Gossart’s portrait print of Charles V is the first known etching on iron made outside German-speaking lands. Ad Stijnman compared the print to Lucas’s portrait of Maximilian and concluded the following: Gossart’s lines are coarser and more uneven than Lucas’s, and do not have any engraved lines; Gossart’s print lacks rust marks, the conclusive proof that an etching is made on iron, but it is nevertheless almost certainly (95 percent likely) etched on iron.26 Iron plates have several technical shortcomings when used for etching: it is not possible to add engraved lines, because iron is harder than copper, and iron rusts quickly, and plate rust typically leaves marks on the print.27 The lack of rust marks indicates that the Braunschweig print is an early impression and was printed before the plate rusted. If the plate was abandoned due to damage, this may explain why only a single impression survives today. It is plausible that Gossart, who traveled widely and was in contact with foreign artists through his engagements at courts from 1508 onward, learned to etch on iron plates from a German artist.

Iron plates became obsolete in favor of copper plates for etching, but—as discussed above—copper required a different mordant than iron. We know that Gossart was interested in etching on copper. A surviving letter to humanist Frans Cranevelt from historian Gerard Geldenhouwer, who was in the service of Philip of Burgundy, records that Gossart had not succeeded in his attempts to etch copper plates, compelling Geldenhouwer to request the recipe for copper mordant from Cranevelt.28 Cranevelt replied with the recipe for nitric acid. Whether Gossart ever received the recipe is not known; however, the letter shows he had the desire but lacked the requisite knowledge to etch on copper for works around this period. He only executed one further etching a few years later, The Mocking of Christ, which was etched on iron.29 Humanists at Philip’s court were important facilitators for Gossart’s forays into etching. Cranevelt had an active interest in experimentation and was knowledgeable in the technical properties of metals and minerals, as evidenced in a letter received by Cranevelt from the Bruges canon Johannes Fevynus that discusses the separation of gold and silver from other metals; Fevynus invited Cranevelt to join him on a visit to a goldsmith in Bruges for a demonstration of the process.30

In his portrait paintings, Gossart immortalized his sitters through careful attention to material markers of status. For example, in his portrait of a man painted around 1528–1530 (fig. 10), the damask silk fabric, slit sleeves, and embroidered collar are depicted with equal attention to the physiognomy of the sitter.31 Adornments and attributes such as the ring, weapons, and hat badge, which signal the status and ambitions of the sitter, are likewise painted with exquisite detail. At the same time, the sitter is cropped and set against a shallow dark green background, which draws attention to Gossart’s artifice, thereby simultaneously suggesting and denying the presence of the viewer before the sitter.32 Gossart brought this illusionism from his paintings into his portrait print of Charles V, seen in the elaborate sleeve, fur cloak, and tapestry.

Gossart modeled his representation of Charles V on German woodcuts and transformed these precedents into a novel visual language of power. The detailed rendering of overlaid fabrics, adjacent materials, contrasting textures, and careful attention to the architectural background are consistent with the character of his painted portraits. In the German woodcut attributed to Weiditz, ornament serves to assert Charles’s identity and status (see fig. 8). The costume and heraldic devices, enhanced with color and printed in gold in a luxury edition of the woodcut on vellum, stand in for the office of the emperor.33 The heraldic devices, architecture, and text are not presented in a visually coherent program but rather serve a symbolic function in alluding to the power and prestige of the sitter.

Gossart adopted this composition and rendered the ornament, costume, and architecture in lifelike terms, in line with his painted portraits. Charles’s hands draw attention to the text underneath his arm, leading the viewer’s gaze downward. The text breaks the illusionism of the portrait. Unfurling across the tapestry and lifting away at top right and bottom left, the text is rendered as an object, albeit one that does not cohere with the rest of the meticulously rendered perspectival construct. This self-aware detail is characteristic of Gossart’s painted oeuvre, as seen in, for example, the parchment on the outer wings of the Norfolk Triptych (1525–1530; Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels).34

The sophistication of Gossart’s illusionism was an important topic for early modern viewers. Van Mander wrote that on the occasion of an imperial assembly at the court of Adolph of Burgundy, Gossart wore painted paper to simulate white silk damask (having sold off the luxurious fabric) and, in doing so, fooled Charles V and his retinue.35 Upon learning the truth, members of the court were delighted by Gossart’s deception, and the emperor marveled at the artist’s ability to imitate costly materials through artifice. The anecdote betrays a familiar rhetorical trope that harks back to Apelles and Zeuxis, where Apelles surpasses nature through artifice and deceives even the most discerning eye with his superior skills. Such a historical reference was far from dry or abstract. Stephanie Schrader analyzed the reception of Gossart’s highly illusionistic painted portraits and concluded that with Gossart’s mimetic powers, the artist surpasses his models, and his skill becomes more valued than any raw material, a conceit that held particular currency at the Burgundian court. With etching, Gossart transferred his prized court aesthetic into a new, multipliable medium. Crucially, he also achieved verisimilitude and illusionism in monochrome. (Recall that the hand-coloring was added by Van Santen only in the seventeenth century.) In Gossart’s print, paper is once again transformed into a more luxurious material, and his etching subsumes the properties of a far richer painted counterpart. These deceptive tricks would have held special appeal in courtly circles, and just as Charles was delighted with Gossart’s faux damask, Philip must similarly have been enchanted by his replicable portrait that aspired to the illusionism of an oil painting.

Political Prints

The two portrait prints under consideration here can be considered political instruments as much as they can be considered artistic statements. Philip of Burgundy commissioned the portrait from Gossart in order to celebrate Charles as emperor-elect upon his return to the Low Countries from Spain on June 1, 1520, and it is probable that Philip also commissioned Lucas’s portrait of Maximilian at the same time.36 Conceived after Charles had been elected but a few months before his coronation as Holy Roman emperor, the two portraits celebrate the regional significance of the emperor-elect and his Burgundian heritage. To show the office of the Holy Roman Emperor in a localizing fashion would have been an important consideration following the election of Charles as Maximilian’s successor, when individual provinces were vying for more power, and the local nobility feared that Charles would continue his grandfather’s attempts at agglomeration.

Dagmar Eichberger has surveyed painted portraits of Maximilian and concluded that the image-savvy emperor changed his public profile in accordance with the prevailing interests of various regional and political contexts.37 Maximilian was unpopular in the Low Countries, and thus for images made in this region he emphasized first and foremost his connections to Burgundy through his position as regent of the Order of the Golden Fleece, which was founded there.38 Portraits of the emperor by Joos van Cleve, known through at least eleven workshop versions, exemplify this type of image, which omits any reference to his imperial status or Hapsburg genealogy (see fig. 6). This Burgundian identity is present in the portrait prints of both Maximilian and Charles.

Philip was an important art patron who had the two emperors to thank for his elevation through the ranks. Maximilian knighted him in 1486, appointed him admiral of the Netherlandish fleet in 1498, and legitimated him in 1505.39 Philip was instrumental in brokering greater independence for the Burgundian territories from Rome, which came about in 1515. Charles appointed Philip Bishop of Utrecht in 1517, after which Philip moved his court from West Soubourg, on the isle of Walcheren in Zeeland, to the episcopal residence, Wijk bij Duurstede, in the province of this cathedral city.40 Philip’s court became an important center of humanism and art in the Low Countries, with visitors including Erasmus and Paladanus, as described in Geldenhouwer’s chronicles.41 Philip was interested in emerging ideas of antiquity and Italian art, as he was in older Burgundian displays of power, and his artistic patronage centered on mediating the two traditions. Both at his previous residence in Zeeland and at Duurstede, Philip helped fund the latest artistic developments. The painter and printmaker Jacopo de’Barbari (ca. 1460/70–1516) and Gossart were both in his employ, engaged in decorating his palace with mythological paintings that featured the first monumental nudes in the Low Countries created in the antique style.42 Geldenhouwer recorded that Philip had an active interest in art and that he was trained in painting and sculpting in his youth, which was in line with contemporary humanist pursuits of artisanal cultures.43 It is worth considering whether the two portrait prints might be understood as an extension of his interest in materials and manufacture. Courtly impetus was critical to the diffusion of early etching, as nitric acid—the requisite mordant for copper etching—was expensive and difficult to access.44 Admittedly, without extant documentation, it is impossible to establish definitively whether a patron such as Philip would have specified that a print commission be etched rather than engraved or would even have distinguished between the two intaglio techniques. Nonetheless, the earliest etchings in the Low Countries are connected to the Burgundian-Hapsburg court, and Philip’s interest in materials makes this an appealing possibility.

Style takes on political significance in the context of the court. In each of the portrait prints, Maximilian and Charles are depicted against a wall and behind a balustrade, which speaks to a common visual language not found in Dürer’s woodcut of Maximilian. Were the two prints made as pendants, or in response to each other? Investigations regarding which portrait was made first remain inconclusive. Christian von Heusinger argues that the portraits were intended as pendants, noting that when they are viewed together, Charles’s gesture is directed at his predecessor and grandfather, signaling imperial lineage and the stable progression of authority. Nadine Orenstein proposes instead that Lucas’s print could have appeared first, and Gossart could have adapted the direction and hand gestures in his portrait accordingly.45

Both portraits have so many elements in common, including the cloth-covered ledge, the positioning of the hands, and architectural features, that it seems likely they were commissioned as pendants or at least were based on a similar model or description. The differing styles of the two portraits suit the respective subjects. As befits a posthumous portrait, the depiction of Maximilian in profile harks back to older models, although Lucas enlivens the sitter with updated references and illusionistic details. Gossart’s portrait of the emperor-elect, by contrast, is starkly modern: Charles boldly meets the viewer’s gaze, which was highly unusual in early sixteenth-century depictions of rulers. Which print came first must remain unresolved, but as Orenstein noted, they were not created together.46 And yet the two artists were doubtlessly aware of each other’s work, although they made their contributions independently.

In his biography of Lucas van Leyden, Van Mander recounts that Lucas and Gossart met when the former arrived in Middelburg, adding that they traveled together to Ghent, Mechelen, and Antwerp.47 This journey took place shortly after the two imperial portrait commissions, but Lucas’s prints would have been available to Gossart before their meeting.48 The two seem to have stood in competition from early on. According to Van Mander, Gossart outshone Lucas at a banquet by wearing more sumptuous cloth, and this encounter characterized the rivalry between the two artists:

Here Lucas van Leijden invited Mabuse [Gossart] and other painters to a banquet which cost him sixty guilders—he did the same in Ghent, Malines and Antwerp where in each case he laid out sixty guilders for the painters; everywhere he was in the company of the aforementioned Jan de Mabuse, who acted in a very stately manner, resplendent in a garment of gold cloth, while Lucas wore a jacket of yellow silk camlet which in the sunshine also had the lustre of gold. But because Mabuse outshone him with his clothing some believe that Lucas was in contempt or at least was less respected by the artists. Something that must be even more at odds with the nature of art and of practitioners of art is that it is believed that Lucas for ever after continually complained about that journey, always suspecting that someone envious of him had given him poison or other; for from that time he was never really in good health.49

This anecdote pertains to more than interpersonal relationships. It has also been used to explain the stylistic shift in Lucas’s prints around 1524 toward muscular limbs, contorted poses and drapery, and stark foreshortening.50 While Gossart’s influence on Lucas has been well established in recent scholarship, it is important to consider how Lucas’s activities as a printmaker might have been a source of interest and inspiration for Gossart, even if the latter did not continue to work in the medium.

Style and technique take on personal meaning in these ambitious imperial portraits. Lucas’s surviving preparatory drawing and Geldenhouwer’s letter about Gossart’s search for copper mordant reveal that these artists were keenly interested in technical experimentation and the stylistic possibilities that the new technique afforded them. The two portraits showcase the respective artistic strengths of Lucas and Gossart. Lucas’s focus on physiognomy is consistent with his accomplished portrait drawings, as is his interest in emotion and narrative, seen in his many religious and genre engravings. Lucas clearly drew on these strengths when faced with a new subject. Likewise, Gossart’s depiction of overlapping surface textures and fabrics, architecture, and bodies articulated in space is also seen in his paintings and his drawing of Christian II.

The two portrait prints include playful conceits and illusionistic details that evince an artistic wit aimed specifically at a Netherlandish courtly context. In Lucas’s print, fools leap off a framing column and into the pictorial field. The fool who holds up the tasseled plaque with Lucas’s monogram and the date (fig. 11) is an allusion to the putti or genii figures frequently found on tomb sculpture, which appear in Weiditz’s woodcut portrait of Charles. Traditionally these figures honor the memory of the sitter, but here the honorific figures are transformed into a playful artistic trope that celebrates Lucas as creator and breaks the illusionism of the sculpted relief. Gossart’s portrait of Charles includes several illusionistic details of varying material surfaces. For instance, the paper scroll of the poem curls away from the tapestry, which itself wrinkles under the ruler’s arm (fig. 12). Unlike Lucas’s hanging plaque, Gossart places his monogram and date on a dramatically foreshortened paper fastened to the background columns. These details and vignettes can be understood as keenly self-conscious artistic interventions. As with Gossart’s painted portraits of Burgundian nobility, the etchings played a role in the artistic self-fashioning of their creators.51

Innovative Prints

Courtly interest in printmaking spurred innovation and experimentation, with novel results that frequently approximated other media. From the first decade of the sixteenth century onward, Maximilian I commissioned grand woodcut projects in southern Germany. Dürer worked with a team of designers, cutters, and printers to produce prints befitting a courtly context: such prints were variously large in scale (his Triumphal Arch measures approximately 3 x 3 meters), printed on vellum, printed in color and gold, and/or hand-colored. Prints commissioned by or for the Netherlandish court, although more modest in scale, must be seen in a similar light. The portraits of Maximilian I and Charles V were luxury prints aimed at a small, elite audience. For a brief moment in the early sixteenth-century Low Countries, etching emerged as a significant technique for elite commissions.

Gossart and Lucas transformed earlier German woodcuts into ambitious portraits, incorporating the latest Netherlandish developments to suit their prints to a local audience. The surviving evidence—Lucas’s preparatory drawing and the letter from Geldenhouwer about Gossart’s search for copper mordant—indicates that the artists were keenly interested in the possibilities of etching. Lucas and Gossart were in good company. Leading artists, humanists, and poets located in and around courts collaborated on ambitious print projects in the service of Burgundian-Hapsburg rulers. Alongside the etched imperial portraits, Nicolas Hogenberg (ca. 1500–1539) produced two important series, the Death of Margaret of Austria (1531)52 and the Coronation of Charles V (ca. 1530–1535). Gossart’s short-lived but documented interest in etching, together with the preparatory study for his print of Christian II (see fig. 9), suggests he may have had further ambitions for portrait prints but was diverted to other projects by his noble patrons.

The courtly context of early etching reveals that the technique has a surprisingly rich history. In the catalogue for a recent exhibition dedicated to Renaissance etching, Nadine Orenstein characterizes early practitioners as a disparate group who approached the technique in widely varying ways.53 Etchings from the first half of the sixteenth century were produced in small numbers, and every printmaker approached the technique differently. The integration of etching into the broader development of northern printmaking has been characterized as a “brief flirtation” or a series of “false starts”; early engagements were fraught with technical problems and were taken up by artists only in short spurts in the first half of the sixteenth century.54As etching became the technique of choice for peintre-graveurs in the seventeenth century, these early examples of the technique were considered unsuccessful in garnering widespread interest and market demand.55

By focusing on a case study from the Hapsburg-Burgundian court, I have shown how etching represented a promising (albeit brief) project in the Low Countries, a project that held interest for courtly and urban audiences alike and provided points of contact between these two social realms. Courtly etchings from this early period were not made for a broad audience, and they consequently did not immediately stimulate widespread interest in the technique. Nonetheless, these early engagements represent a significant application of print technologies in the service of the court. Elite patrons such as Philip of Burgundy, who was said to have trained as a goldsmith, may indeed have been interested in the tools, processes, and production of printmaking as part of a broader humanistic interest in both manual and theoretical aspects of art production.56