The Donne Hours (Louvain-la-Neuve, Archives de l’Université, Ms A2) manuscript is well known to art historians under the name of the Louthe Hours. Produced by Simon Marmion of Valenciennes in collaboration with the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook working in Bruges, this manuscript lies at the center of a group of books of hours produced by artists of different provenances. This paper looks more closely at how this wonderful book of hours was produced.

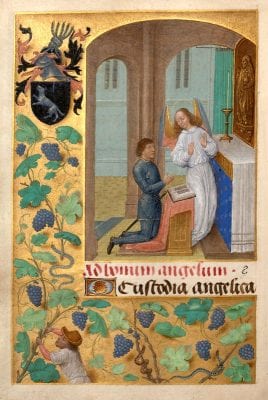

A book of hours conserved in the archives of the University of Louvain-la-Neuve (Ms A2)1 is well known to art historians as the Louthe Hours. The owner and his coat of arms appear twice in the volume (fols. 13 and 100v) (fig. 1). In 1921, he was identified as Thomas Louthe, on the basis of the calendar, which includes saints of English origin (Edward the Confessor, Edmund, Richard, Dunstan, Kenelm, Oswald).2 This identification was accepted for a long time. However, in 1998, Lorne Campbell pointed out that the Louthe family coat of arms was “Sable, a wolf salient argent” accompanied by a “crescent argent” and that the latter item is missing on the shields painted in the book of hours.3 It also turned out that the sable field of the shield was painted over a blue (azure) layer. The original coats of arms — “Azure, a wolf salient argent” — are in fact those of Sir John Donne, as they appear on a triptych painted for him by Hans Memling (National Gallery, London, inv. NG 6275).4 Sir John was, like his father Griffith, in the service of Richard, Duke of York. Thereafter, he was a faithful follower of Edward IV until the latter’s death. In 1461 he was appointed Usher of the Chamber. Around 1465 he married Elizabeth Hastings. Between 1465 and 1469, he was an Esquire of the Body and received offices in the city of Calais, where he appears in the archives from 1468 until 1483. Donne also accompanied Margaret of York to Bruges in 1468 on the occasion of her marriage to Charles the Bold. Later, in 1470–71, he probably followed Edward IV into temporary exile in Bruges.5 He also took part in numerous diplomatic missions. John Donne died in 1503. While not having the reputation of a bibliophile, he possessed a number of manuscripts.6 The contents of his book of hours, which was made for Sarum use, are quite simple. After the calendar (fols. 1–12v) come the Hours of the Virgin (fols. 13–88), an antiphon to the Trinity (fols. 89–90), a section devoted to the five joys of the Virgin (fols. 90v–95), suffrages or intercessory prayers to saints (fols. 95v–118), the seven penitential psalms and litanies of the saints (fols. 119–145), incipits of the Psalms (fols. 146–149), and finally the prayer Obsecro te (fols. 150–154). On fol. 154v, a prayer has been added in sixteenth-century script. Fol. 156 carries indications on the beginnings of the seasons, in Latin and French,7 again later additions.

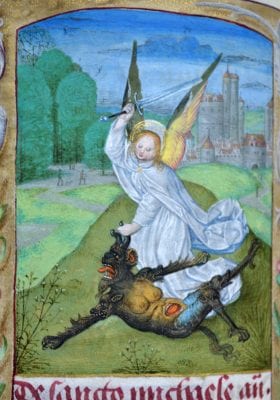

Two illuminators produced the illustrations for this volume. The majority of the miniatures were attributed in 1923 to Simon Marmion.8 Features characteristic of the works attributed to this artist, particularly two leaves that may have belonged to a breviary for Philip the Good, the only illuminated work by Marmion to be documented,9 can be found in them. The faces of the figures, with forms characteristic for Marmion, are modeled on top of a middle shade base tone using light-colored highlights placed essentially on the forehead, the nose, and the cheekbones, and reddish brown hatchings in the lower face (fig. 2). The highlights modeling the garments, applied with great freedom and considerable mastery, demonstrate the genuine virtuosity of an artist who also practiced easel painting (fig. 3). The scenes are placed in large landscapes with low skies, seen from high vantage points (fig. 4).

The collaboration of a second artist in the calendar and in ten miniatures of the Donne Hours was observed only in 1959 by Leon Delaissé,10 who placed this artist in the circle of the Master of Mary of Burgundy. Later, this ascription was narrowed down by Antoine De Schryver, who identified him as the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook,11 an attribution that has remained unchallenged ever since.12 One finds indeed the hand of the Dresden Prayerbook Master in these miniatures’ rather squat figures with their well-rounded faces, their garments modeled with large amounts of very precisely applied hatchings (fig. 5). Saint Sebastian’s half-naked body on fol. 103v also displays this master’s use of gray hatching to model the flesh tones (fig. 6).

The Louthe Hours, here renamed the Donne Hours, are central to a key issue with regard to the work of Simon Marmion.13 Despite their long attribution to this artist, the miniatures were disassociated from his production by Antoine De Schryver in 1969.14 This scholar observed that some books of hours attributed to Marmion and dating mainly from the end of his career had been produced in collaboration with artists working in Bruges, Ghent, or Antwerp. As Marmion does not appear to have left Valenciennes after settling in this city around 1457, De Schryver concluded that these books had been produced by another artist working in Marmion’s style but active in Ghent. He regrouped six books of hours around a miniaturist whom he named the Louthe Master, after the Louvain-la-Neuve manuscript,15 later adding a seventh book of hours to this corpus.16 he splitting of the group that De Schryver had initiated was carried much further by Edith Hoffman,17 who attributed Marmion’s production to three different hands: the Master of the Altarpiece of Saint Bertin, the Tondal Master, and, for the last period, the Louthe Master. This thesis was strongly criticized by Otto Pächt18 and Charles Sterling,19 leading most recent scholars to demonstrate the consistency of the production grouped around the figure of Marmion. In 1983, Thomas Kren,20 while adding further books of hours to De Schryver’s list,21 attributed their authorship back to Simon Marmion himself. Through careful stylistic and iconographic comparison, Kren demonstrated the homogeneity of the group, explaining that the apparent heterogeneity was to be blamed on the participation of a workshop. In 1990, at a symposium dedicated to a manuscript of the Tondal Visions attributed to Marmion (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms 30), this idea was amplified by numerous authors, who reaffirmed the unity of the Marmion group and the identity of the Louthe Master,22 with the exception of De Schryver, who remained attached to his thesis.23

Since then, other books of hours have been added to the group of manuscripts on which Marmion worked together with Ghent or Bruges artists.24 Further advances have also recently been made in this area. The two most recently added manuscripts of the group (La Flora Hours, Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, IB.51; and a book of hours for Rome use, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 28345) had been dated prior to Marmion’s death in 1489, due to his participation in their implementation. However, the Master of the First Prayerbook of Maximilian and the Master of the Prayerbooks of around 1500, who also took part in their illustration, were active only from the 1490s onward. Closer examination of the Marmion miniatures revealed that they had been glued onto pages cut out in a passe-partout system.25 This was probably done after the illuminator’s death, which matches better with the periods of activity of the Ghent artists who contributed to the production of these books of hours.

An initial remark is called for following the presentation of the problem of the books of hours produced by Marmion that were inserted into the corpus of the Louthe Master. In this group of works, two very distinct categories can be detected.26 On the one hand a series of manuscripts on which Marmion worked alone were intended for northern France, as indicated by their calendars and the localized forms of their liturgies These are a book of hours in Tournai (Bibliothèque de la Ville, Cod. 15), the Gros Hours (Chantilly, Musée Condé, Ms 85), another book of hours (Turin, Palazzo Madama, Museo Civico, 0446/M), the Hours of Jean Rolin II (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, Res. 149) and the Berlaymont Hours (San Marino, Calif., The Huntington Library, HM 1173).27 In the second and larger group, Marmion worked in collaboration with artists from Bruges or Ghent. It is this specific problem that, I believe, needs to be investigated closely by a thorough study of the manuscripts. A comprehensive examination of the Donne Hours was performed using scientific methods (microscopy, ultraviolet light analysis, infrared reflectography, X-ray fluorescence), which provided numerous indications with respect to this manuscript and its authors.28 In this article, however, I will use the results of microscopy and X-ray fluorescence to concentrate on the issue of the production of the manuscript: how it was put together and what are the links between the two illuminators who painted it. In particular, careful observation under the microscope and codicological analysis of the volume have enabled me to arrive at most of the findings that are discussed below.

In 1992, Bodo Brinkmann29 located a single leaf painted by Marmion that represents Saint Anne and the Virgin and Child, with a short prayer to them on the reverse. Its layout and dimensions match those of the Donne Hours. Then in a private collection, this leaf has since been sold (London, Christie’s, June 2, 2004, lot 7). Brinkmann suggested placing it between fol. 88 and 89 of the Donne Hours, in the preamble of the section containing the Five Joys of the Virgin. He also posited that this leaf formed part of a bifolium with fol. 96, which is currently a single leaf. This hypothesis is plausible, but if a leaf is added at the beginning of this quire, this gives an odd number of leaves, as fol. 89 is also a single leaf.30 On the other hand this miniature cannot be part of the suffrages following the text of the Five Joys of the Virgin, as a representation of Saint Anne appears there already (fol. 97v); furthermore in this part of the book the scenes are on the reverse of the leaves. These are the only two places where this short prayer to Saint Anne and the Virgin and Child could have been placed. The stylistic and dimensional similarities tend to place this leaf in the Donne Hours, unless another similar book of hours existed. It is difficult, however, to answer the question of its original placement in the manuscript.

The Donne Hours represent a quite complex task of analysis. The majority of the miniatures can be attributed to Simon Marmion, who was active at that time in Valenciennes. However, ten of them, along with the decorations of the calendar, were clearly produced by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook, active in Bruges. The issue of the place of production is therefore an important one: where were the Donne Hours produced and how did the two artists divide up the work? If the illuminators did not themselves travel, what solutions were adopted in order to create these mixed hours?

The parts of the Donne Hours painted by Marmion and those painted by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook differ stylistically but also codicologically. The first difference lies in the layout of the illustrations. The scenes painted by Marmion are surrounded on three sides by decorated borders, with the binding margin free of any ornamentation (fig. 1), while the miniatures painted by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook have decoration in all four sides (fig. 7). The margins have a gold background on top of which are painted white acanthus leaves and flowers, except for the calendar, where gray and gilded (or ochre) backgrounds alternate. Upon examination of the painting technique, however, significant differences become noticeable. The margins around Marmion’s miniatures are painted on a very thin layer of shell gold,31 with the acanthus leaves and flowers then painted on top. A light brown shading was brushed in to give the impression that these decorative elements stand out from the background. Gold stippling was added to give greater relief to the background gold layer (fig. 8). The margins painted around the miniatures of the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook were produced on the same principle, but they lack the fineness of execution of the decorations that accompany Marmion’s illustrations (fig. 9). The shading is much less subtle and heightens the contrast between the decorative elements and the gold layer. The gold stippling that delicately models the background in Marmion’s work becomes here systematic and unrefined. The margin contours are also different. Marmion defined their area, on both the inside and the outside, by a gold line applied when the marginal decoration was substantially or fully completed (fig. 8). This same technique was applied to the gilded, ochre, or gray margins of the calendar illustrated by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook (fig. 10). By contrast, in the body of the manuscript, the margins around the miniatures by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook are delimited by a purple line that was applied ahead of the production of the border decoration (fig. 9). On some of these leaves, the line forming the lower part is doubled, as if it were a correction. Thus the layout, the painting of the margins, and the way they are delimited serve to distinguish three distinct parts in the volume: the calendar, the body of the book illustrated by Marmion, and the leaves attributed to the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook in the suffrages.

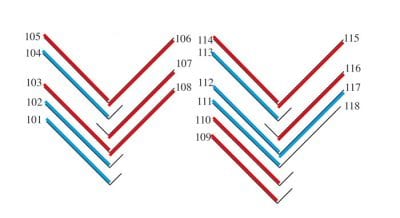

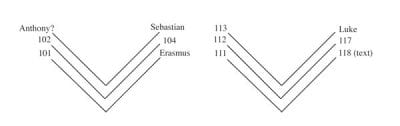

Closer examination of the quires shows that the hand of the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook appears in only two places: the calendar and in quires 15 and 16.32 The structure of the two quires in the suffrages is heterogeneous. These are composed of bifolia and single leaves (fig. 11). None of the bifolia contains simultaneously miniatures by Marmion (in blue on the diagram) and by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook (in red). Bodo Brinkmann had already noted that the miniatures and their borders had been produced by two workshops, each operating separately.33 But he also assumed that the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook had retouched some faces in Marmion’s compositions and had even completed some miniatures barely sketched out by the latter artist. He saw in the highlights on Saint Leonard’s forehead (fol. 112v) a retouching by the Bruges master. However, examination under the microscope shows this retouching to have been applied to a large loss in the paint layer (fig. 12). The filling of this loss, no doubt formed well after the completion of the miniatures, must have taken place much later and in all likelihood has nothing to do with the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook. It could be a retouching done when the azure field of the coat of arms and of the lambrequin was overpainted in black.

As for the hypothesis of miniatures barely sketched out by Marmion and completed by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook, Brinkmann based this on the observation that the trees in the background of Saint Michael (fol. 108v) (fig. 13) differ from those, bulbous and nearly spherical in form, painted by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook. From this he concluded that Marmion left the book of hours unfinished and that it was completed by the Bruges master. However, the trees, in the shape of elongated balls, do not correspond either to those painted by Marmion.34 The delineation of the decorated margins is also different in the leaves produced by Marmion and those by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook, suggesting that they could not have passed through Marmion’s hands. The heterogeneous structure of quires 15 and 16 also shows that they have been fundamentally reworked. The work by the two hands is clearly separate, and it is likely that the miniatures by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook were added later. These miniatures must have been produced in a short space of time, which could explain the presence of trees that do not reflect the style of the two masters involved. Indeed, the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook could have asked one or more illuminators, from his own workshop or not, to paint part of the landscapes while he himself did the figures, making it possible to work on two leaves simultaneously and so shorten the time taken to prepare the miniatures.

If one assumes that the miniatures by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook were produced during a second phase of the making of the manuscript, a reconstruction of the original two quires painted by Simon Marmion can be attempted (fig. 14). For this the miniatures painted on the reverses by Marmion (Anthony, Eligius, Fabian, Barbara, Leonard, Thomas of Hereford, and Mary Magdalene) and the texts that accompany them need to be taken into account. In order to have the painted scenes match the texts facing them, it seems that the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook was forced to replace some images produced by Marmion (Saints Sebastian, Erasmus, and Luke, plus another unidentified saint, who could be Saint Christopher).35 The saints who were probably added in this way to the series produced by Marmion are Thomas Becket, Quiricus and Julitta,36 Michael, Gabriel, Nicolas, and Margaret. This reconstruction is, however, not without problems. For a start, the mixing of male and female saints does not usually appear in suffrages. In addition, the easiest way to introduce several saints into this part would have been to insert an additional quire between quires 15 and 16, which would have involved the replacement of only one miniature in order to match images and text. Could the solution adopted in the Donne Hours reflect the desire, perhaps by the owner, to present the saints in a specific order?

What then were the different stages of the production of the manuscript and can it be determined where these steps were taken, at Valenciennes, where Marmion was living, or in Bruges, where the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook was working? As in any manuscript, the text was written first, as shown by the way many letter stems are covered by the gold background layer of the margins. The ink on the leaves painted by Marmion and by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook has been analysed by X-ray fluorescence (XRF).37 In both cases it contains iron, copper, and zinc, with traces of potassium and manganese. It is therefore a metallo-tannic ink,38 produced from the same recipe. However, this should not be read as indicating that both parts were written simultaneously, as this was a widely used recipe. This finding does not contradict the hypothesis of saints being added in the suffrages, as the text could have been copied in the same scribe’s workshop, using the same ink recipe, with a shorter or longer time gap.

Another codicological element confirms that the text on the leaves painted by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook was produced at a different time. On the leaves painted by Marmion, the ruling pattern is made with diluted red ink, with the limit lines extending to the edges of the sheet. This is not the case for the leaves painted by the other illuminator, where the ruling pattern is scarcely visible, having probably been made with a metalpoint, and with the limit lines not extending to the edges of the leaves. In addition, the prick holes, which are visible at times, are much more pronounced and elongated in the part painted by the Bruges master.

The particular layout of the pages with the illuminations produced by Simon Marmion, with marginal decoration on three sides only, appears to occur only in the north of France. Marmion himself used this layout in at least two of his books of hours: one of which, dating to the 1470s, is conserved in only a single leaf (Paris, École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Mn. Mas. 130), and a second one that once belonged to Jean Gros (Chantilly, Musée Condé, Ms 85), which is probably contemporary with the Donne Hours. Other manuscripts from northern France also have this layout; for example, the Hours of Marguerite Blondel (London, British Library, Add. 19738),39 painted by the Rambures Master, or again a series of manuscripts attributed by Dominique Vanwijnsberghe to the Master of the Claremont Hours, whose activity he places in Lille.40 This is therefore an initial indication that the miniatures by Marmion and the margins surrounding them were done at Valenciennes. Careful examination of fols. 13 and 100v, where human figures appear to be made in reserves left in the background of the border decoration, shows that they were produced by the same hand that painted the main miniature (fig. 15). The shell gold background and its decoration were painted first, after which Marmion painted the miniature and the human figures in the margins. After this the border decoration was completed, as shown by the fact that the acanthus leaves close to the figure of the owner on fol. 13 run slightly over into it. This interpenetration of the margins and the figures shows that the border decoration was undertaken simultaneously with the miniatures, and therefore in one place: Valenciennes. Margins of a similar style and handling are found in the work of Simon Marmion. The Hours of Jean Gros conserved in Chantilly (Musée Condé, Ms 85) show borders that are probably from the hand of one of the two artists who seem to have produced the margins of the Donne Hours. The Gros Hours were produced in northern France, as indicated by the saints in the calendar. On examining the manuscript, I was able to determine that the emblems and coat of arms of Jean Gros, from a well-established Bruges family, were added in a second phase, indicating that originally the book of hours was probably not intended for this Bruges owner. Other examples of similar margins are present in works by Simon Marmion’s entourage: three leaves from a book of hours (Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Ms 482.123) and four leaves from a book of hours, one representing a Descent from the Cross (London, Sotheby’s, December 4, 2007, lot 28). However, it is an isolated folio belonging to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles (Ms 45) that confirms the location of these margin decorators in northern France (fig. 16). This leaf contains the beginning of the Terce of the Hours of the Cross from a book of hours for Cambrai use.41 The marginal decoration on it is by one of the hands that decorated the margins of Marmion’s miniatures in the Donne Hours, including in particular the same dragonfly as on fol. 104v of the Louvain-la-Neuve manuscript. Its position, even as far as its legs, indicates that it comes from a model book used in the same workshop. Many pieces of evidence point to the fact that the margins and the miniatures were produced in northern France. Their link with Marmion probably locates this production at Valenciennes.

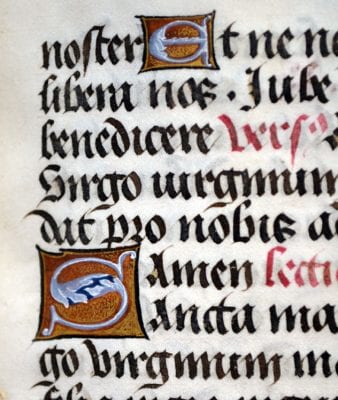

The calendar of the Louvain-la-Neuve manuscript was illustrated by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook (fig. 10), placing its painting in Bruges. This artist, whose production consists mostly of books of hours, seems to have specialized in this exercise. His hand appears in the calendars of no less than twelve books of hours, in which he sometimes also executed miniatures.42 The scenes depicting the labors of the months in the Donne Hours often appear in these calendars in a more or less developed fashion. They are also used in full-page miniatures illustrating the calendar of the book of hours from which the artist takes his name (Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Ms A.311).43 In the calendar of the Donne Hours, the text was written first, as the stems of some of the letters are covered by the border decoration and initials. This was followed by the initials and then the borders were painted, as shown by the edges of the initial at the bottom of fol. 1, which is under the gilt background of the margin (fig. 10).

So far, the division of labor seems clear: the calendar was decorated in Bruges by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook; the rest of the volume was illustrated in Valenciennes in Simon Marmion’s workshop. In a second stage, a modification of the suffrages was carried out in Bruges by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook. However, study of the initials raises a problem. The majority of these are done on a brown background with shell gold stippling (fig. 17). The letters are painted in gray highlighted with white, sometimes with a few strokes of blue. All are in the same style and were probably painted by the same workshop, both in the part produced by Marmion and that by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook. In addition, with the exception of the calendar, they were done after the miniatures and borders (fig. 8), whereas this type of secondary decoration was generally painted before the miniatures. Where were the initials produced? Very similar ones, probably by the same artists, appear in some manuscripts produced in collaboration by Marmion and illuminators from Ghent or Bruges, as in the Emerson-White Hours (Cambridge, Mass., Houghton Library, Ms. Typ. 343),44 making it impossible to determine with certainty where they were produced. On the other hand, these initials are found in manuscripts produced in Bruges on which Marmion did not collaborate, such as the Hours of Philip the Fair (London, British Library, Add. 17280), illustrated by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook,45 or the Gros-Carondelet Hours, recently sold at Jörn Günther Rare Books (Brochure no. 13, 2013, no. 22).46 The Bruges origin of these manuscripts allows one to envisage these initials having been added by a Bruges workshop.

All this means that the Donne Hours were probably put together in more phases than might seem at first sight. After writing the text, the volume was separated into two parts: on one hand the calendar, produced in Bruges, on the other the body of the text, with the margins and miniatures painted in Valenciennes. Once this part had been completed, the text returned to Bruges where the initials were added. Both parts were then combined and possibly shown to John Donne, who requested additional miniatures. The margins and miniatures for these were produced in the workshop of the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook in Bruges. It is, however, possible that this last step took place before the completion of the initials, since they were also painted last of all in the part added by the Bruges master.

The presence of miniatures by Simon Marmion and the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook in the same manuscript is difficult to explain, knowing that Marmion remained continuously at Valenciennes from 1457 until his death and that his name does not appear in the archives of the Confraternity of Saint John the Evangelist in Bruges. This led De Schryver to postulate that it was impossible for these two artists to have worked together and to imagine the involvement of a Ghent illuminator working in a style very similar to that of the Valenciennes master. If the Louthe Master is indeed Marmion, we must admit that the book was completed in two places. It should also be noted that the trade and sale of illuminated leaves produced outside Bruges had been forbidden in this city since 1457, unless bound in complete books.47

To explain the participation of artists from different places, Bodo Brinkmann took as his basis his codicological analysis of the Salting Hours (London, Victoria and Albert Museum, L2384-1910) to determine that Simon Marmion’s workshop could have produced miniatures without marginal decoration on separate folios, which were then inserted into the book produced in Bruges or Ghent without the need for the illuminator to travel there in person.48 If this scenario is possible in the case of the Salting Hours, where the miniatures by Marmion are painted on single leaves inserted at the front of the quires and surrounded with borders with figures painted by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook, it is not the case in the Donne Hours. We have seen that in this latter manuscript the marginal decoration was done in Valenciennes and the leaves containing the miniatures by the Bruges artist were added during a change in the suffrages. It is therefore not individual leaves that were imported but the main part of the text, consisting of the Hours of the Virgin, prayers to the Trinity, the Five Joys of the Virgin, the suffrages, and the penitential psalms, which traveled from Bruges to Valenciennes and back and was then finalized in Bruges. The calendar never left Bruges, where it was decorated in its entirety. It can then be argued that books or parts of books could travel between workshops, which were sometimes very distant one from another. One can even assume that, to avoid accidents and texts getting mixed up during the journey, and especially for their protection, these could be placed in temporary bindings. Moreover, in this way there was no infringement of the prohibition imposed by the Bruges Confraternity.

Marmion’s collaboration with Bruges or Ghent illuminators could thus have taken several forms. The first, as shown by the Donne Hours, was to transport a portion of the manuscript to Marmion’s workshop. Such a journey could have been made along with other manuscripts than books of hours. Indeed, Marmion illustrated texts written for Margaret of York by David Aubert: a volume containing three texts, the Vision de l’ame de Guy de Thurno, the Visions du chevalier Tondal (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Mss 30 and 31),49 and Listoire de madame sainte Katherine by Jean Miélot (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF 28650).50 In the colophon, David Aubert mentions that the text was transcribed in Ghent in 1474. In this case, too, the manuscript probably traveled in order to be illustrated. The second form of collaboration would have been the sending from Valenciennes of single leaves, which would subsequently have been inserted into the manuscript, as in the Salting Hours (London, Victoria and Albert Museum, L2384-1910).51

The solutions adopted to produce these manuscripts were thus probably not uniform. Among these different procedures, a common point nonetheless remains: their production was very carefully planned. This planning must have been done by a coordinator who took the customer’s order, assembled the materials and the various craftsmen involved in producing the manuscript, and then distributed the work among them. This person must have had a close relationship with the artists working on the books. In addition, in the case before us, this planning needed to be all the more precise as it required prior agreements with artists from geographically separated production centers, adapting to the availability of the different intervening workers, contact with them, and time to transmit information between two more or less distant cities, as well as the planning and implementation of the journeys of the manuscripts. This person could be one of the links in the production of manuscripts whose names can rarely be linked with any specific production: the bookseller (libraire).52 The insertion of miniatures in a passe-partout system in the two books of hours most recently added to the group in which Marmion collaborated, as already noted above, could also indicate the activity of a bookseller who maintained commercial links with him or even his heirs. Marmion’s manuscripts are not the only example of books produced in two geographically distant locations and possibly under the baton of a bookseller. In 2002, Thomas Kren pointed to a series of books of hours written by Jacques Dubreuil, who was resident in Paris.53 While some show a close collaboration between Parisian craftsmen such as Maître François, others were illustrated by artists from Tours. Notwithstanding this, the secondary decoration of all the books in the series was undertaken by the same Parisian workshop. Such collaborations between craftsmen living in different cities, even if not the norm, are thus not unique.

Were the Donne Hours and the other books of hours on which Marmion worked in collaboration with artists operating in other cities than Valenciennes produced under the direction of a single bookseller? Or of two booksellers, one the successor of the other? It is difficult to answer this question, especially in our present state of knowledge. The place where these one or more booksellers were active is also difficult to determine. We have seen that in the Donne Hours the work was shared between Valenciennes and Bruges, with final modifications made in Bruges. These changes could possibly indicate that the bookseller turned for the latter to the artist who was the most accessible and probably physically closest to him, this being the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook. But the bookseller might also have worked out of Ghent or Antwerp, given that in the group of books of hours in which Marmion collaborated there are also artists from both these cities. The case of Antwerp is, however, more complicated because only one artist from this group lived and worked there: Lievin van Lathem. A native of Ghent, Van Lathem moved to Antwerp but also spent time in Bruges. It is therefore possible that he maintained strong commercial ties with both cities. Considering that Marmion illustrated texts written by David Aubert for Margaret of York in Ghent, this city is also a possible location for a bookseller employing Marmion. The Scheldt axis has often been highlighted in the dissemination of art in the southern Netherlands,54 and Tournai, midway between Ghent and Valenciennes, is another possible location. The fact that in 1468 Marmion joined the Tournai painters’ guild, without residing there, suggests that he attached importance to maintaining commercial links with this city.55 In addition, his brother Mille, who had lived and worked in Tournai from 1466, and was still living there in 1473, was accepted there as a master in 1469. Should these links with the city of Tournai be seen in this context? It is difficult to give a definite answer, but this possibility cannot be excluded.

The study of the Donne Hours demonstrates that the use of codicological and stylistic examination as well as careful observation of the different stages of production of a book can make a huge contribution to our understanding of certain issues such as that of the “Louthe group.” Their application to a number of manuscripts has already permitted the re-evaluation of certain methodologies and conclusions. The contribution of scientific methods is particularly important, and their use, in parallel with more traditional codicological and stylistic studies, needs to be extended in order to arrive at a broader vision of the way illuminated manuscripts were created.