During his approximately eight-year stay in Rome, the noted Utrecht Caravaggist, Dirck van Baburen, responded to the work of some of the Eternal City’s most influential painters. It has long been known, for example, that Van Baburen appropriated motifs and pictorial devices from such eminent Italian artists as Caravaggio and Bartolomeo Manfredi as well as the Spaniard, Jusepe de Ribera. The present essay argues that the art of the little-known Italian master, Angelo Caroselli, also exerted a formidable impact upon the Dutchman, particularly the latter’s portrayal of genre subjects produced after his return to his native Utrecht.

In the course of conducting research for my recent monograph on Dirck van Baburen (ca. 1592/93–1624), I became acquainted with the work of the somewhat obscure but ever-fascinating seventeenth-century Italian painter Angelo Caroselli (1585–1652). Better known today among specialists than the public, Caroselli was a native Roman who, according to his two biographers, Giovanni Battista Passeri and Filippo Baldinucci, was entirely self-taught.1 He apparently possessed sufficient talent to make flawless copies of the work of the most esteemed masters, among others, Poussin and Raphael.2 Such was his reputation in this arena that even Vincenzo Giustiniani, one of the eminent Maecenases of the era, owned a tiny painting of Saint Matthew by Caroselli that “imitated” a picture by Caravaggio.3

Caroselli initially enjoyed a rather peripatetic career; thanks to the work of several scholars, his once perplexing meanderings have been clarified.4 Although he enrolled in the Academy of St. Luke in Rome in 1604, Caroselli spent time in Florence, possibly in 1605–06 or 1610 and then returned to his native city. In 1611–12, he received a contract to paint two prophets and a Pietà (fig. 1) for the ceiling of the Vittrice Chapel in Santa Maria in Vallicella (Chiesa Nuova).5 The artist remained in Rome for several years, marrying there in 1615 and assisting Giovan Francesco Guerrieri (1589–1657) in the decoration of the then newly constructed Palazzo Borghese in the Campo Marzio.6 In November of 1616, Caroselli and his wife quit Rome, perhaps spending several months in Piedimonte Matese in the province of Caserta. The couple then continued on to Naples, where they remained (along with their three children who were born there) until 1625.Thereafter, Caroselli and his young family returned to Rome for good.

Turning now to Dirck van Baburen, the young Dutch master most likely arrived in Italy in the summer or fall of 1612, if not in early 1613.7 We will probably never know what specific Italian cities Van Baburen visited or whether he did so before or after he had settled in Rome, but one thing is certain: he spent most of his approximately eight-year stay in Italy in the Eternal City, where he established a solid reputation relatively quickly.8 Van Baburen’s years in Rome only partly overlapped with those of Caroselli. Like sizable numbers of their fellow artists, the two resided in parishes in the northern section of the city.9 Thanks to the Stati delle Anime (registers of persons), censuses conducted annually at Easter time by Rome’s parish churches, we know that until his departure in late 1616, Caroselli continued to live in the parish in which he had been born, that of Santa Maria in Lucina.10 The Stato delle Anime for the nearby parish of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte for 1619 records Van Baburen’s presence and that of a fellow artist, David de Haen, in a house on the Piazza della Trinità della Monte; they were living together with a certain Cornelio Brabrandia, who was probably a painter too.11 The following spring, in what would be Van Baburen’s last year in Italy, 1620, the Stato delle Anime for Sant’Andrea delle Fratte once again listed him and De Haen, who were now lodging with the French painter Nicolas Régnier (ca. 1588–1667), a servant, and an apprentice, “Giovan Antonio Piemontese.”12

Unfortunately, we lack documentation for Van Baburen’s living arrangements prior to 1619. All the same, given the proximity of their respective parishes, their shared profession, and the fairly tight networks of painters and patrons in early seventeenth-century Rome, it is plausible to hypothesize that Caroselli and Van Baburen knew one another. Regardless, Van Baburen was most certainly familiar with Caroselli’s work. Consider, for example, the Dutch painter’s famed altarpiece The Entombment (fig. 2), painted in 1617 as part of a group of canvases made for a Spanish patron to adorn the Pietà Chapel in the church of San Pietro in Montorio, perched high on the Janiculum Hill in western Rome.13 It is well known that The Entombment testifies to its maker’s knowledge of the chiaroscuro effects and volumetric forms of Caravaggio’s famous painting of the same subject (fig. 3), which hung at that time in the Vittrice Chapel in Santa Maria in Vallicella.

Van Baburen’s exposure to Caravaggio’s work must have impressed upon him the fact that strongly illuminated figures set against a dark background literally stand out forcefully within a dusky chapel. Van Baburen also deployed the same basic compositional structure as Caravaggio, with its wedgelike arrangement of figures set at a diagonal, cascading downward toward the body of the dead Christ. In Van Baburen’s Entombment, however, the stone of the tomb, which, like the Italian’s, also serves as the stone of unction (with its eucharistic implications), is more tablelike while the body of Christ has been rendered in an upright, almost seated position. It is likely that Van Baburen appropriated this unusual motif from Caroselli. As we noted above, Caroselli had adorned the ceiling of the chapel directly above Caravaggio’s work with paintings portraying two prophets and a Pietà. His Pietà shows Christ in a similar position (fig. 1).14

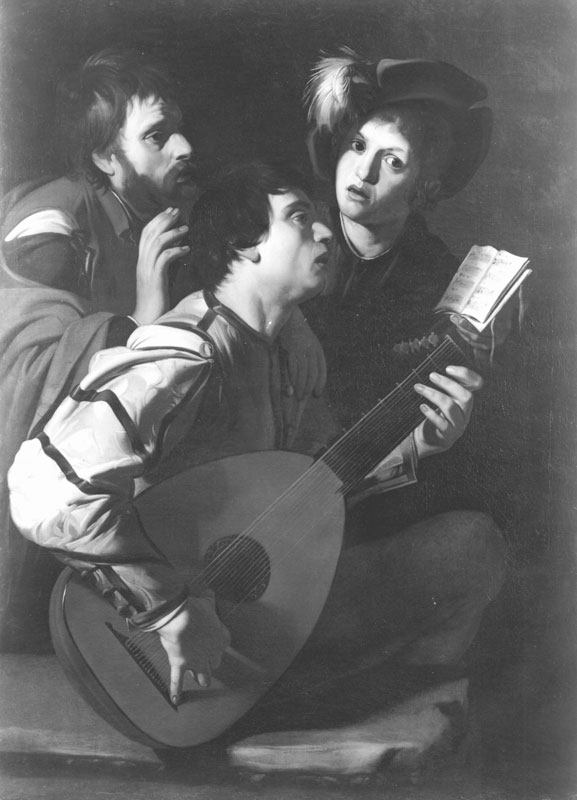

The poses of Van Baburen’s and Caroselli’s figures of the dead Christ exhibit distinct affinities that hardly seem coincidental. All the same, one finds even more striking parallels between the two artists’ genre paintings. Caroselli’s singular pictures of this sort, striking for their vivacity and, at times, their vulgarity, owe much to the work of the Ostianese painter Bartolomeo Manfredi (1582–1622), who resettled in Rome around 1600.15 Manfredi soon embarked upon a hugely successful career as an interpreter of Caravaggio’s idiom, especially for a younger generation of mostly foreign painters. In essence, Manfredi successfully adopted specific stylistic and thematic devices from Caravaggio’s art and, in the process, created new pictorial paradigms that proved highly influential.16 Consider, for example, Caroselli’s Man Singing (fig. 4).17 While singers and related musical performers can be found in the work of Caravaggio, Manfredi’s interpretation of this theme (fig. 5), employing half- to three-quarter-length figures in unarticulated, restrictive rectangular spaces, infused with rich coloration gently modulated by chiaroscuro, must have resonated resoundingly with Caroselli. As several scholars have noted, Caroselli’s Singing Man evidences similar qualities.18 Yet, the close-up, oblique view of the performer as well as his homely face distance him from the more elegant figures that routinely inhabit Manfredi’s prototypes.

It is precisely these earthy features of Caroselli’s work and the very subjects themselves that appear to have made an indelible impression upon Van Baburen, although one that would not manifest itself until the latter painter had returned to Utrecht. Van Baburen’s own Singing Man of 1622 (fig. 6) is, on some levels, unexplainable without Caroselli ’s prototype.19 Both artists portray performers in angled poses holding musical scores while gazing at the viewer. And in both, the costumes are fanciful; Van Baburen’s performer may be dressed in a more distinctly “antique” manner than is Caroselli’s, but the wonderful medallion pinned to the men’s hats appears in both, even if the former’s hat is topped with marvelous feathers.20 Much more significantly, the singer’s gesture of the raised open hand, so often credited to the Utrecht Caravaggists as a motif of their own devising (fig. 6-7), likely owes its origins to Caroselli’s picture.21 The few specialists who have noticed the correspondences between Caroselli’s and Van Baburen’s Singers find them puzzling. They assume that the better-known Dutchman must have influenced the Italian. This, in turn, has led to the awkward argument that Van Baburen’s painting possibly reflects lost pictures of the same subject that he supposedly made in Rome.22 It seems not to have occurred to anyone that perhaps the Dutch master (and his Utrecht colleagues) adopted the motif from the older Italian painter. And while there have been disagreements over the dating of Caroselli’s Singer and related genre paintings (see below), there is really no reason to doubt that they were painted during his first Roman period, when he was most strongly under the spell of Manfredi.23

Caroselli also produced some memorable images of audacious prostitutes that are virtually unparalleled within the broader context of early seventeenth-century Italian art. His Violinist and Courtesan (fig. 8), for example, a tondo on slate, depicts two boisterous figures whose assertive physicality in combination with their close proximity to the picture plane imparts to them an uncannily palpable presence.24 The coarse-featured buxom prostitute holds coins in one hand, while she simultaneously points to the brooch on her hat representing Danae, her Ovidian sister who was likewise seduced by money (both literally and figuratively).25 With mouth agape, her client, sporting a fantastic costume crowned by a plumage-sprouting cap, plays his violin. The forceful palpability and vulgarity of Caroselli’s spirited scene is matched by others he made of analogous subject matter (fig. 9).26 In essence, his approach in these indecorous works in pressing earthy figures into the immediate foreground and clothing them in outlandish and often suggestive attire anticipates Van Baburen’s own portrayals of prostitution such as his famed Procuress (fig. 10) and his lesser known Loose Company (fig. 11), painted in Utrecht in 1622 and 1623, respectively.

None of these observations are, of course, meant to imply that Van Baburen was captivated by Caroselli’s pictorial precedents to the exclusion of all else. After all, his familiarity with Northern European visual traditions, to cite just one example, is well known. Rather, within the greater ambit of Caravaggesque painting, Caroselli seems to have provided the younger painter with the most pertinent thematic and stylistic paradigms for certain subjects he would portray upon his return to his native country. Manfredi and for that matter, the Spaniard, Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652),27 in their capacity as innovative interpreters of Caravaggio’s idiom, were undeniably critical for Van Baburen’s development, but his ongoing dialogue with contemporary painting in Rome inevitably led him to appropriate motifs, stylistic devices, and so forth from the work of other more “minor” masters such as Caroselli.