A little-known Germanic Passion diptych from the late fifteenth century—comprised of the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross and the Chicago Crucifixion—was recently reunited, foregrounding a complex interchange of compassionate co-suffering between the two panels. The figures of Christ and the Virgin turn and twist their eyes and faces, balancing their attention between different points of empathetic contemplation within and without the frames. As they engage with the beholder and with one another, they encourage meditation on the Holy Face of Jesus by manipulating mental images in a repetitive cycle of foresight, hindsight, and exegetical reflection.

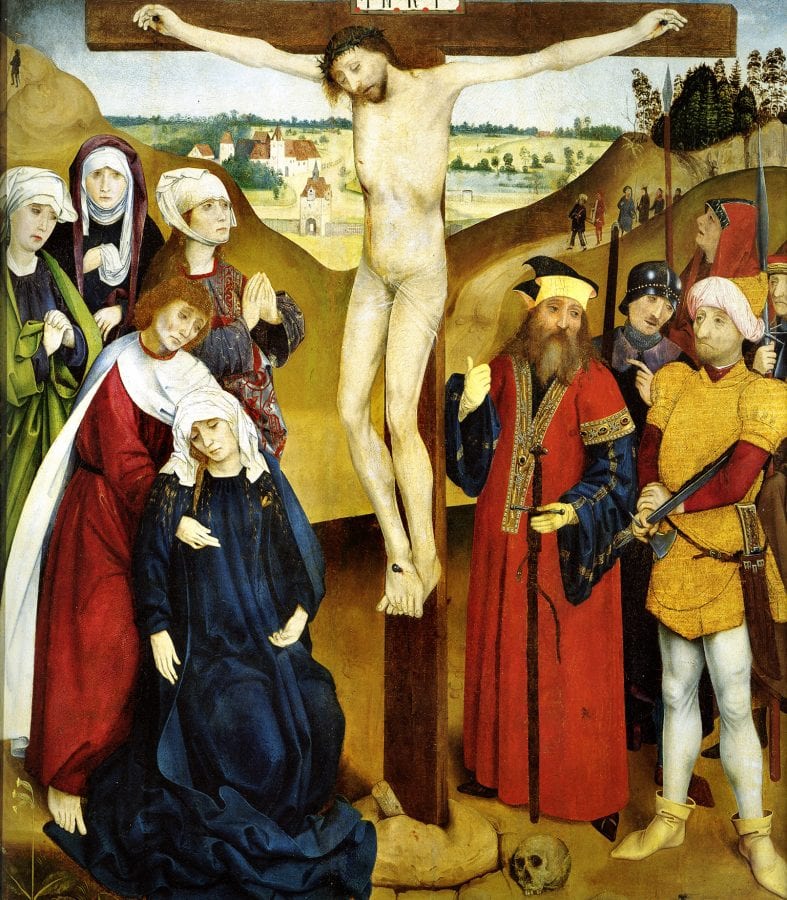

In 1944, a small, Germanic panel depicting Christ’s agonizing march to Calvary entered the collection of the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (fig. 1). The scene takes place outside the crenellated walls of Jerusalem where Christ has fallen beneath his cross on the rocky Via dolorosa, the “sorrowful way” leading to the place of execution. On the left, the Virgin and Saint John lead a group of mourners from beneath the ominous, pronglike grating of the city gate. In the center, Christ turns imploringly toward the viewer, his brow streaked in blood and his eyes squinted in pain, while brightly dressed tormentors brandish a hammer and a halberd, soon to be employed in nailing their victim to the cross and piercing his side. The Atlanta painting was originally hinged in a diptych with a Crucifixion now in the Art Institute of Chicago, the two panels likely coming from the same spruce tree, with nearly identical dimensions and frames, faux marble backings, and compositions executed in the same style (fig. 2).1 In the Crucifixion, the dead Christ hangs from the cross, eyes closed and mouth ajar, while blood from his pierced feet runs down the wood and drips onto the skull of Adam. He is surrounded by witnesses, some mourning, some hostile, with the city of Jerusalem in the distance. On Christ’s right, the distraught Virgin has collapsed to the ground as Saint John gazes grimly at the gaping wound in his side. Standing just over a foot in height, the paintings were likely the focus of private household devotion. Their intimate size and emotional quality would have facilitated meditative prayer and other practices of early modern affective piety aimed at reforming the soul.

Before arriving in the United States, the diptych formed part of the art collection of Count Johann Nepomuk Wilczek (d. 1922) at Kreuzenstein Castle, outside Vienna. Meticulously painted, the panels are both in remarkably good condition, and the frames seem contemporary with the year 1494, which the artist inscribed in red at the base of the cross in the Chicago panel.2 The E. and A. Silberman Gallery in New York City acquired the diptych by 1934, dismantled it, and sold Christ Carrying the Cross to Otto Karl Bach of Grand Rapids, Michigan, and the Crucifixion to Charles H. Worcester in Chicago. The works have received little more than passing acknowledgment in the scholarly literature. In his catalogue of Germanic panels in America, published in 1936, Charles L. Kuhn dismisses the Chicago Crucifixion as being of “slight interest” “aside from the fact that it is definitely dated.”3 The Art Institute’s medieval and Renaissance catalogue from 2008 evaluates the Crucifixion in more detail but stops short of investigating the diptych’s iconography beyond noting a “conventional” quality that often characterizes market production.4

In 2014, the panels were reunited for the first time and exhibited in Atlanta for a year and then in Chicago as part of the inauguration of the Art Institute’s new medieval galleries. With the diptych temporarily reunited, it is possible to observe a remarkable interaction between the suffering Christ and the co-suffering Virgin that not only plays out within the individual panels but, more importantly, extends across the frames dividing them. Far from being an arbitrary, marketplace pairing, the pendant images closely cooperate to construct a poignant devotional argument. In a circuitous cycle of anguish and empathy, the mother imitates the son, who in turn imitates the mother. They incline and gaze toward one another within and without their frames, but significantly, their apprehension of each other’s suffering is not based solely on corporeal vision. As they engage across the frame, Mary and Jesus also regard each other through their imaginations, prophetically looking ahead and mentally looking behind. Moving well beyond the formulaic and conventional, they model a dichotomy of physical and spiritual seeing that votaries meditating in front of the diptych could have imitated. The pictorial images, fastidiously rendered in paint and gold, would have prompted viewers to simultaneously consider mental images created in their hearts as they prayerfully interacted with the bleeding Christ and the Mater dolorosa.

Questions of Attribution and Iconography

The Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross and the Chicago Crucifixion have never been securely attributed to a particular artist or even a particular school, and theories for the provenance have volleyed back and forth between Bavaria and Austria. The name of the southern German painter and engraver Mair von Landshut appears penciled on the back of the Atlanta panel, but suggestions have also included the circle of the Master of the Karlsruhe Passion, the Tyrolean painter Urban Görtschacher, and the Austrian Hapsburg Master.5 Ultimately, none of these possibilities is altogether convincing. In fact, the panels’ feathery landscapes, fading into blue and green hills toward the horizon, combined with their gold grounds and expressive, agitated style, have much in common with many circles of painting in southern Germany and Austria. Of particular interest is an association made by Martha Wolff connecting the Chicago Crucifixion to the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Munich workshop of Jan Polack.6 The Bayerisches Nationalmuseum houses many of Polack’s monumental altarpieces, which recall the Atlanta and Chicago panels in their use of landscape, modeling, and emotional intensity. Wolff is quick to note, however, that disparities in scale and function make any connection between Polack and the Atlanta-Chicago diptych tenuous. She concludes by suggesting that manuscript miniatures may be a more relevant source for tracking the authorship of the panels.7

In addition to its rich collection of Polack altarpieces, the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum possesses a small-scale devotional diptych markedly similar to the Atlanta-Chicago ensemble (fig. 3). Painted around 1470 in southern Germany, it pairs Saint George’s battle against the dragon with a depiction of his martyrdom.8 Like the Atlanta and Chicago paintings, the Saint George panels feature a gold ground with engaged frames. The landscape is more generalized, and the figures betray some awkwardness in their positions and proportions, but the diptych renders metal armor, piles of heavy drapery, and highlights in a way analogous to the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross and the Chicago Crucifixion. Most importantly, the facial types parallel one another in their simplified features and elongated dark eyes. Although less painstaking in its details, the Saint George landscape makes use of the same kinds of castle structures and loosely painted foliage with golden highlights. Moreover, the executioner’s stance at Saint George’s martyrdom is strikingly reminiscent of the position of the halberd-bearer in the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross, and both figures wear nearly identical red costumes and hats. The color palettes are comparable, and both diptychs contain dusty paths dotted with similarly rendered stones. While these traits do not provide sufficient evidence to assign the works to the same creator, they point to a common artistic milieu, most likely in southern Germany.

In terms of subject matter, paired Passion narratives occupy a prominent place in both the private and public art of the late Middle Ages and early modern era. The Wiener Schottenaltar, a monumental polyptych painted around 1469 for the high altar of the Benedictine Abbey of Our Lady of the Scots in Vienna, contains an extensive cycle of Christ’s suffering and death on the exterior of its shutters. When the altarpiece is closed, an image of Christ carrying the cross appears side by side with a Crucifixion scene (figs. 4 and 5). The Atlanta-Chicago diptych and these pendant scenes from the Wiener Schottenaltar are notably similar in iconography, for both adhere to venerable conventions for representing the Passion in northern European painting.

Particularly close to the composition of the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross is a painting by the Lower Rhenish artist, Derick Baegert of Wesel (fig. 6).9 In both works, the Virgin and Saint John huddle outside a city gate enclosing elegant towers and steeply pitched roofs, while Simon of Cyrene and the three main soldiers are positioned in much the same way. The threatening figure in red behind Christ is especially important in this regard. The placement of his hands is analogous in the two works, although in the Atlanta panel he strikes the Lord with a long halberd, while in Baegert’s image his grip on the spear morphs into a raised fist in one hand and a tightly held club in the other. The position of Baegert’s Christ, stooped beneath the cross, conforms to the stance of Jesus in the Atlanta painting. Both figures extend their right hands to offset the weight of their collapsed bodies, but while the Atlanta Christ’s hand is firmly planted on the ground, Baegert’s hovers, somewhat illogically, over the folds of his robe and the foot of one of the tormentors. Both images seem to have relied on workshop drawings, but Baegert’s floating hand indicates a more disjointed assembly of these standardized types. Moreover, key figures in the Chicago Crucifixion align with the composition of a Crucifixion from Freising, dated to circa 1490 and now in Munich (fig. 7).10 The crucified Christ and Saint John are distinctly similar, as are the gesturing Jewish official and the soldier holding a shield decorated with a fearsome head.

Returning again to the Wiener Schottenaltar, it is noteworthy that, like the Atlanta-Chicago diptych, the juxtaposition of scenes invites the viewer to follow the winding Via dolorosa from the heated narrative of the left panel to a more static and somber moment before the crucified God in the right-hand image.11 In the Vienna paintings, the march to Golgotha climbs steeply up the rocky hillside in the right background so that the vantage point in the adjoining panel is much loftier, with a broader sweep of sky on the horizon. In the left panel of the Atlanta-Chicago diptych, the forward movement of the soldier in the yellow doublet propels the viewer’s eye along the rocky road before twisting the gaze back along the face of the mountain to reach the aqueduct in the distance. The Crucifixion, hinged on the right as the end point of the meditative journey, also stands on elevated ground, with the cityscape distant and diminished in size.

As worshipers imaginatively plodded along the Via dolorosa with Christ, visual cues embedded in the diptych would have prompted reflection on a series of well-known typological musings.12 For instance, in the Atlanta panel Christ is jerked along the path like an animal, with a cord tied around his waist, fulfilling Isaiah’s prophecy that he shall be “brought as a lamb to the slaughter.”13 The unrelenting tugging of the rope and the weight of the cross have brought him tumbling to the ground. On his hands and knees in the dirt, his humiliation not only appeals to the viewer’s compassion but also vividly recalls imagery from the Psalms: “But I am a worm, and no man; a reproach of men, and despised of the people.”14

As with many depictions of the journey to Calvary, there is a great disparity between the pained but stolidly beatific faces of Christ and his mourners and the leering expressions and agitated postures of the tormentors.15 Good and evil have been segregated to the left and right halves of the composition, respectively, with the righteous forming a compact block just outside the gate. They emit a palpable quietude as the diminutive Simon of Cyrene humbly helps Christ lift the heavy cross, while a calmly composed Virgin prays wordlessly and Saint John carries a small book to remind viewers of his account of the Passion, written in mute letters.16 Christ himself pauses in the path, his silent and patient agony embodying Isaiah’s prophecy that the Messianic victim would be “as a sheep before her shearers is dumb.”17 The soldiers, by contrast, twist and strike around him in a violent frenzy, emblematizing the dangerous and predatory animals described in the Psalms: “Many bulls have compassed me . . . They gaped upon me with their mouths, as a ravening and a roaring lion,” “they make a noise like a dog . . . Behold, they belch out with their mouth: swords are in their lips”; “save me from the lion’s mouth: for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns.”18 The open, jeering mouths of Christ’s accusers counter the stillness of his mourners, and the artist calls attention to their darting glances by highlighting the flickering eyes of the soldier in red with bright flecks of white and accenting his armor-clad companion’s gaze with a startling splash of aquamarine. This pronounced contrast between raucous violence and quiet endurance has a corollary in the topography of the landscape, as the verdant hillsides and light blue river are cut through by a desiccated road to Calvary, littered with stones, like the “rough valley, which is neither eared nor sown,” where the Israelites killed the sacrificial heifer.19

The devotional center of the Atlanta panel is the Holy Face of Jesus. Looking up from his fall, Christ has angled his head to align with the front of the picture plane, while the intersecting beams of the cross operate like a wooden frame, riveting the viewer’s attention on his countenance. The plaited band of green thorns further delineates his brow and gives rise to a secondary “crown” in complementary red that drips down his forehead in a carefully articulated wreath of blood. As with most representations of the Holy Face, the votary’s confrontation with this image elicits a spiritual experience that trades on artistic tropes, inextricably connected to the process of image making, miraculous artifice, and replication.20

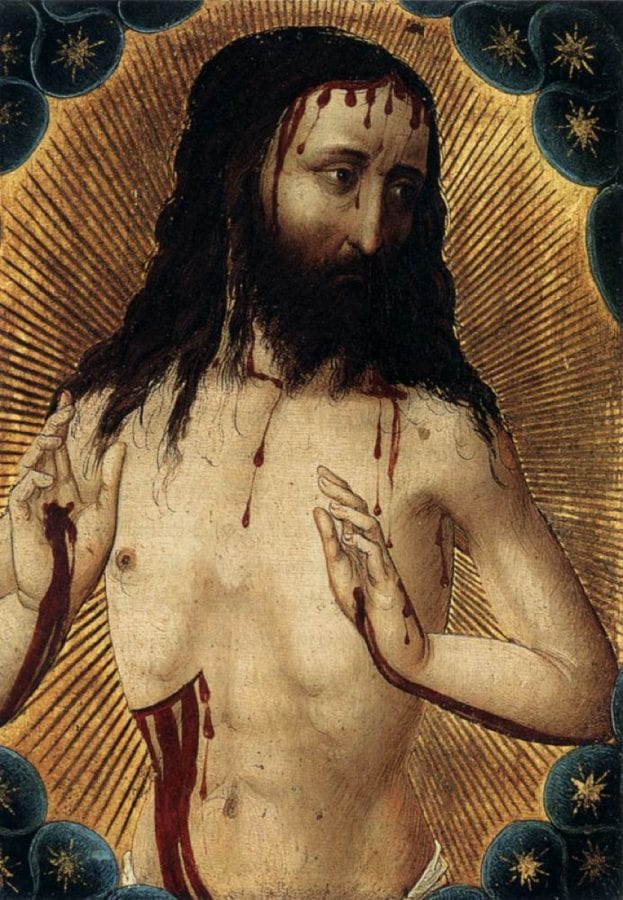

The archetypal likeness of Christ was created supernaturally as he traversed the Via dolorosa. According to legend, a woman named Veronica offered him a clean towel on which to wipe his face. From the tears and bloody sweat that stained the cloth, a perfect portrait of Christ took shape—a vera icona, or “true image” of the face of Jesus. Created “without hands,” this trace of Christ’s countenance on white fabric echoed the mystery of the Incarnation, whereby God was made representable in the pure body of the Virgin Mary. Artists replicated this most prized relic of Christianity countless times, particularly in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance when depictions of Saint Veronica’s towel—known as the sudarium—were richly indulgenced. Even when the sudarium is not explicitly depicted, however, the affective and theological associations of its legend accrue to many close-up portraits of Christ. For instance, pairings of panels by Albrecht Bouts and his workshop stage poignant interactions between the Virgo doloris and her son, who is represented in the Aachen ensemble as Ecce Homo (fig. 8).21 Chronologically, the event from which the Ecce Homo image arises occurs before Christ meets Saint Veronica, and yet his countenance, deeply pierced with thorns and streaming in blood and tears, inspires fervent compassion from the viewer akin to the pity that prompted Saint Veronica to extend her towel. Moreover, by fracturing the Ecce Homo narrative into a dramatically cropped view of Christ’s head, Bouts evokes the disembodied Holy Face that would soon be impressed on the cloth of the sudarium and that is already replicated with equal authenticity on the heart of the Lord’s co-suffering mother in the right panel.22

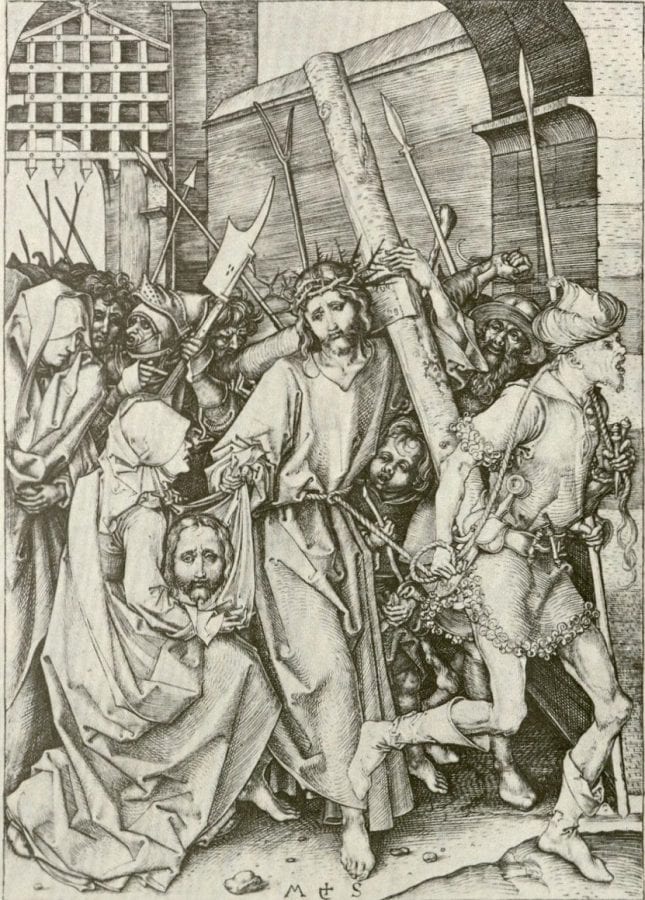

Naturally, the sudarium has special relevance to representations of Christ carrying the cross. Many of these images contain a flurry of narrative detail, in contrast to Bouts’s telescoped diptych, and yet they often belie the potential to be “frozen” and distilled by the votary into a personalized encounter with the Holy Face.23 Sometimes Saint Veronica appears in the jostle of mourners and mockers crowded around Christ, the face on her sudarium bearing an express likeness to the face of its prototype beside her. At times, the acheiropoietic head (“made without hands”) exhibits a tactile, three-dimensional quality, as in an engraving by Martin Schongauer, in which the Holy Face floats above the folds of the cloth and stares at the viewer with an intensity and directness that takes preeminence over the gaze of the living Christ (fig. 9). In other instances, Saint Veronica offers the Lord a blank towel, encouraging the viewer to imaginatively complete the miracle that transferred Christ’s features to the cloth.

Still other images, like the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross, eliminate Saint Veronica entirely, and only the frontal, anguished head of Christ prompts an implicit meditation on the sudarium. In another Schongauer engraving of the same subject, it is difficult at first to locate the demure Saint Veronica, standing at the edge of the procession and expectantly cradling a length of cloth in her arms (fig. 10). In the midst of the violent commotion around him, Christ has briefly paused to fix his eyes on the viewer. A soldier roughly jerks him forward by the top of his robe, and in a fraction of a second the guard behind him will snap a sharp lash across his back. Yet Christ arrests this fierce narrative and turns, angling his head so that his large face seems disembodied against the precisely rendered beams of the cross.24 In fact, Schongauer’s Holy Face hovers above the fine waves of woodgrain in much the way that the miraculous replica tends to hover over the folds of the sudarium, impervious to distortions from the cloth. Christ’s gaze calls forth the empathetic ministry of his viewers, inviting them to step forward from the edge of the crowd and emulate Saint Veronica by engraving the features of the Holy Face into the fabric of their willing hearts, in much the way that Schongauer’s print was itself engraved into a copper plate and pressed onto paper.25

As mentioned above, the Atlanta panel facilitates a similarly timeless devotional exchange between the votary and the Holy Face of Jesus through the frontal position of Christ’s head, framed by cross beams and wreathed in thorns and blood.26 To draw further affective and theological attention to Christ’s countenance, the artist engages viewers in a visual “puzzle.” Oddly, the figure leading Jesus with a rope and the soldier brandishing a hammer have exchanged headgear.27 The dark, metal helmet clearly belongs to the henchman dressed in armor, while the soft hat, made from scarlet cloth with iridescent, yellow-green lining, completes the costume of the figure in the yellow doublet and red stockings. On the one hand, these mixed-up hats reinforce the sense of barbaric foolishness that frequently characterizes the soldiers who taunt Christ, but at the same time, their exchange spotlights a much more sinister misplacement of headgear: rather than his rightful crown, the King of Heaven wears a circlet of thorns as the ridiculed “King of the Jews.” This pitiable taunt carries exegetical weight, for the exchange of a heavenly crown for a thorny one is willfully enacted by Christ himself through the Incarnation, whereby the immortal God “made himself of no reputation and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men.”28 The circlet of blood springing up from where the spines dig into Christ’s flesh points to the loving conclusion of his condescension: “And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross.”29

The visualization of the Incarnation propounded in Saint Paul’s epistle to the Philippians is echoed in the retelling of Christ’s torments from the fourteenth-century Meditationes vitae Christi. This well-known Franciscan text notes that in humble acceptance of the Passion, Jesus “bowed his head for the crown of thorns.” The reader’s attention is then drawn to the wounded visage of the Lord with the same vivid detail that characterizes paintings of the Holy Face: “In the bitterness of your heart, contemplate him now, and especially that head of his, full of thorns, as it is struck with the reed, heavily and often . . . Obviously, those thorns penetrate most painfully, and cause blood to flow over his entire sacred head.” The author concludes with a pointed allusion to Philippians and the grim irony of this mockery against the “King of the Jews”: “And so he submitted to it all, as if he were a slave.”30

When questioned by Pontius Pilate about his kingship, Jesus replied, “ My kingdom is not of this world.”31 The headgear exchange in the Atlanta panel epitomizes this subversion of divine monarchy and even becomes a twisted form of imitatio Christi as the two soldiers mimic in jest the willful debasement that their victim enacts in love. Their cruel parody stands in marked contrast to the imitative suffering of Christ’s disciples. A pertinent corollary image comes from the Lamentation panel of Hugo van der Goes’s Vienna diptych (fig. 11). Here, the wealthy Nicodemus, identified in Saint John’s gospel as “a ruler of the Jews,” humbles himself in emulation of the dead servant-king as he genuflects beside the body of Christ.32 Significantly, his hat, which he has deferentially removed and left in the right foreground, manifests his internalization of Christ’s pain, for it bears the Lord’s crown of thorns twined above its brim.33 It has been noted that the thorns appear to be taking the place of the ornamental tiaras that sometimes encircle royal hats, as if Nicodemus had himself exchanged his rightful headdress for the fearsome crown of Christ.34

In the Atlanta painting, Simon of Cyrene demonstrates similar empathy. At the other end of the spectrum from the jeering soldiers—and literally standing at the other end of the cross—he willingly hefts Christ’s burden, modeling devout imitation by “tak[ing] up his cross, and follow[ing]” the Lord.35 An informative drawing of Christ carrying the cross by Hans Holbein the Elder connects the Christological imitation of Simon of Cyrene with the perfect likeness of the Lord imprinted on Saint Veronica’s towel (fig. 12).36 In the image, Simon lifts the end of the cross, precisely as he does in the Atlanta panel, but here he also leans forward and bows his head to physically conform to the pained posture of Christ’s body. That Simon has been “imprinted” with the Lord’s likeness is made self-evident by Saint Veronica, who complements and explicates his piety as she and Christ together hold the sudarium. Itself an “imitation” and simulacrum of Jesus, her precious towel becomes an ensign for Christ’s heavenly kingdom, calling the humble to take up their crosses like Simon, in contrast to the Roman standard directly above, which musters the ranks of a worldly empire with an abbreviation of Senatus popolusque romanus.

Circles of Compassion and Holy Face Devotion

The Virgin Mary is the preeminent imitator of Christ, and in the Atlanta-Chicago diptych the conformities between mother and son cycle within and between the two panels in complex exempla of devotional empathy. In the Chicago Crucifixion, the Virgin has fallen to her knees, her soul pierced with compassion for the dead Jesus, her own deathlike collapse broken by the supporting arms of Saint John. It is critical to note that her crumpled position on the ground resembles the stance of Christ, sprawled in the dust of the Via dolorosa in the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross. That the Mother of God more blatantly imitates the Atlanta Christ than she does the crucified Jesus beside her is bolstered by an intriguing departure from the underdrawing of the Chicago panel (fig. 13). The Virgin’s right hand was initially intended to be turned upward so that it resembled the pierced hands of Christ on the cross, as if she had suffered a sympathetic wound in her palm. In the finished panel, however, the artist turned the Virgin’s hand downward, causing it to conform to the right hand of Christ in the Atlanta painting. The Chicago Virgin’s raised left hand also mirrors the left hand of her son as he holds onto the cross.

The Chicago panel thus embeds Mary’s memory of Jesus’s fall into her swoon on Calvary. This compelling compositional idea is not unique to the diptych, however. Indeed, the corresponding scenes from the Wiener Schottenaltar achieve a similar effect (see figs. 4 and 5). Crushed by the weight of his cross, the Vienna Christ looks purposefully toward his unconscious mother in the adjoining panel. As Simon of Cyrene helps heft the burdensome cross, so Saint John sustains the Virgin’s dead weight, a trope that is repeated in the Atlanta and Chicago panels.

The shared agony between the Mater dolorosa and Christus patiens was a central component of late medieval piety. The scriptural account of the Crucifixion provides the basis for their empathetic encounter at Calvary, when Christ looks down from the cross at his mother and lovingly commends her to the care of Saint John:

Now there stood by the cross of Jesus his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus therefore saw his mother, and the disciple standing by, whom he loved, he saith unto his mother, Woman, behold thy son! Then saith he to the disciple, Behold thy mother! And from that hour that disciple took her unto his own home.37

The Meditationes adds a circular component to the pain of mother and son. The Virgin co-suffers so acutely that her heart is crucified alongside the Lord, and at the same time, Christ’s compassion for his mother’s suffering adds a new level of anguish to his own torment:

And all these things are said and done in the presence of his most sorrowful mother, whose own suffering greatly increased her son’s suffering, as his did hers. Virtually she was hanging on the cross with her son; and she would have chosen rather to die with him than live on.

His mother stood by the cross of her son . . . She did not take her eyes off her son; she was devastated as she poured her heart out in prayer for him to the Father: “Father and God eternal, You willed that my son be crucified; I cannot ask You to give him back to me now. But You see the great distress in his soul now. Please, lighten his suffering. Father, I commend my son to You.” In turn, her son prayed silently to the Father for her: “My Father, You see how afflicted my mother is. It is right for me to be crucified, but not her. But she is here on the cross with me! It is enough for me to be crucified: I bear the sins of all people. She deserves no such thing. You see her desolate, afflicted with deep sorrow all the day long. I entrust her to You, to make her sorrows bearable.”38

Fittingly, the dead body of Christ in the Chicago Crucifixion is still oriented toward his mother, memorializing the finals words and last affections of his heart that were directed to her. In the Atlanta Christ Carrying the Cross, the Virgin stands near the city gate, prayerfully watching her son from a distance, “commending” him to God. Their interaction aligns closely with the narrative of Christ’s trek to Golgotha in the Meditationes:

Because his grief-stricken mother could not get close to see him on account of the crowd of people, she went quickly with John and her companions by another shorter route, to try to meet him by getting there before the others. She intercepted him at a crossroad outside the city gate, picking him out, weighed down by the huge wooden cross which she had not seen before. She was stricken half-dead in her anguish, and was incapable of speaking a word to him, nor the Lord to her, hurried along as he was by those who were leading him to be crucified.39

The intertwined suffering of the Virgin and Christ also takes center stage in the mystery plays that proliferated in Germany and the Low Countries from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries. Performed for large crowds as part of the liturgy, processions, and festivals, these highly visual spectacles offer an important framework for understanding devotional art.40 The fourteenth-century Sankt Galler Passionsspiel makes the following injunction:

Behold, good ladies,

how Mary felt,

when she heard and saw

the suffering of her beloved son.

She suffered with him, he suffered with her.

This you must believe:

that her sorrow grieved him more

than his own agony.41

Passion plays frequently place the Virgin’s pain at the heart of the drama, using her grief as the pivotal hinge for accessing the pitiable humanity of Christ.42 To this end, Mary’s tumultuous monologue—the Planctus Mariae, or Marienklage in its German versions—functions as a devotional instrument for spectators. It invites them, first, to empathize with the mourning of a relatable mother:

Mourn, faithful souls,

mourn, good sisters . . .

Let mothers’ hearts mourn for

the wounds of mother Mary.43

Having established an identification with the Virgin’s human grief, the Marienklage then transforms the audience’s empathy into Christological conformitas, as “the wounds of mother Mary” are revealed to be one with the wounds of her son:

This sad spectacle

of the cross and lance

deeply wounds

the sign enclosed

within the virgin mother …

While I humbly look up at his

down-turned head and see

the thorns on his head

and the holes in his hands

with their bloody fingers;

while the wound in his side

continues to pour forth . . . 44

The fifteenth-century Erlauer Marienklage underscores the identification between mother and son with especially violent imagery:

Your blood reddens me,

his death kills me,

his pain anguishes me . . . 45

Not surprisingly, the reciprocal anguish of the Marienklagen derives from the same affective tradition of Franciscan spirituality that produced the Meditationes.46 The staging of the Passion in the Atlanta and Chicago panels operates similarly to these texts, with the cycles of empathy between Christ and Mary playing out like a painted Marienklage.

The diptych’s circles of compassionate sight and memory ultimately depend on and give rise to a stirring iteration of Holy Face devotion. Saint Veronica and her sudarium appear consistently in German Passion plays, in which the miraculous image of Christ’s countenance is likened to a salve for the sorrowing spirit, a salvific sign, and the fulfillment of the saint’s wish to have the Lord’s “great torture” “plant[ed] in [her] heart.”47 In the Meditationes, spoken words fail the Virgin and her son at their meeting “outside the city gate,” and it is “face-to-face” gazing that constitutes their only communication.

Unlike most images of the sudarium or Schongauer’s cultic presentation of Christ’s head, the Holy Face of Jesus in the Atlanta panel is not completely frontal, nor does Christ make direct, piercing eye contact with the votary. Rather, the Lord’s attention slips back and forth between three points. On the one hand, he emphatically faces viewers meditating before the diptych, his squinted eyes and open mouth appealing to their mercy. At the same time, he tilts his head back slightly, as if acknowledging his mother behind him and responding to her silent prayer with a prayer of his own. Most importantly, though, his face turns marginally to the right, and his pupils veer beyond the painting’s frame toward the Virgin in the Crucifixion panel. For her part, the Chicago Virgo doloris turns blatantly to the left, appearing to meet the gaze of her son looking up from the dusty road in the Atlanta image. Close inspection of Mary’s face, however, reveals that she stops short of fixing her eyes on the fallen Christ. Instead, her gaze shifts back to the right, toward the dead Jesus suspended from the cross.

In this way, the communion of Christ and his mother vacillates between different registers of perception. The slight inclination of Christ’s head in the Atlanta panel responds in historical time to the fixed gaze of the Virgin standing behind him. Since her “suffering greatly increased her son’s suffering, as his did hers,” Christ’s apprehension of his grieving mother becomes a catalyst for prophetic foresight as he looks ahead to behold the culmination of Mary’s sorrows in the adjoining panel when she collapses with exhaustion on Calvary. The painting thus construes Christ’s own collapse beneath the cross as an empathetic anticipation of the Virgin’s swoon. With the position of his head and eyes delicately balanced between present and future manifestations of his mother’s pain, Jesus configures his own suffering as a filial act of imitatio Mariae, as Passion becomes Compassion.

The Chicago panel situates the kneeling Virgin between two similar poles of perception. Although she turns her eyes to the dead Christ beside her, her vision is partially obscured by the white veil draped over her uplifted hand. The forcible twist of Mary’s head in the opposite direction of her eyes only underscores the visceral reaction of a stricken mother who cannot bear to see her son’s broken body and yet also cannot bear not to look at him. As in the Marienklagen, relatable, maternal pain leads to conformitas, as the Virgin’s suppression of corporeal vision gives precedence to a different mode of perception: her memory of Christ on the path to Golgotha, articulated in the eyes of her mind as clearly as it is rendered in paint on the facing panel. It is significant, in this regard, that in the Atlanta painting, Christ’s recognition of his mother standing behind him is also obscured, unseen, and only acknowledged by a subtle tilt of his head. The riveting revelation that transforms his body into the likeness of the Virgin’s future suffering is transmitted through the noncorporeal register of prophecy and foresight. In the Chicago panel, it is hindsight, rather than foresight, that draws the Virgin’s attention away from the somber aftermath of the Crucifixion and back to a vivid memory of the Via dolorosa. Having now witnessed the entirety of her son’s Passion, it is fitting that Mary “looks back” on the Atlanta panel from a higher vantage point, literally positioned on the elevated hill of Golgotha with the cityscape in the distance behind her. The panoramic spectacle from this lofty lookout analogizes the razor-sharp register of sight in the Virgin’s memory. As if unwilling to cease rehearsing the suffering of her son, the swooning dénouement of Mary’s Compassion recapitulates the pitiable fall at the commencement of his path to execution.

These circles of foresight, hindsight, and external and internal vision intersect constantly. The diptych presents the cycle of empathetic perception through the configuration of mother and son, who not only adopt similar postures but also turn and tilt their heads and eyes, as if pulled backwards and forwards by the circular trajectory of their Passion and Compassion. This pictorial strategy, which ultimately inscribes memory and spiritual apprehension in the “empty space” between the two panels as the rationale “hinging” the scenes together, is one of the most compelling aspects of the diptych. It bears witness to a finesse of devotional argument, too easily obscured by deceptively routine iconography. In fact, a similar logic “hinges” together the Saint George paintings, discussed previously (see fig. 3). As the executioner swings his sword toward St. George’s neck, the kneeling martyr gazes calmly toward the other half of the diptych, remembering the blade he wielded against the demonic dragon and contrasting it with the death blow that will shortly admit his soul into paradise.

When the Atlanta and Chicago panels were propped open at an angle, Christ and the Virgin would have faced each other from across the frames. This “sight line,” which contradicts the constraints of time and place, is common in northern devotional art from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Bouts Ecce Homo and Mater Dolorosa, cited earlier, provide a good example, with mother and son pivoting toward one another yet not communicating by corporeal sight. The Lord’s blood-shot eyes stare thoughtfully into space, while his mother’s gaze—already blurred with profuse tears—is lowered. In short, their meditative vision of one another is internal, imaged in the heart rather than in the eye.

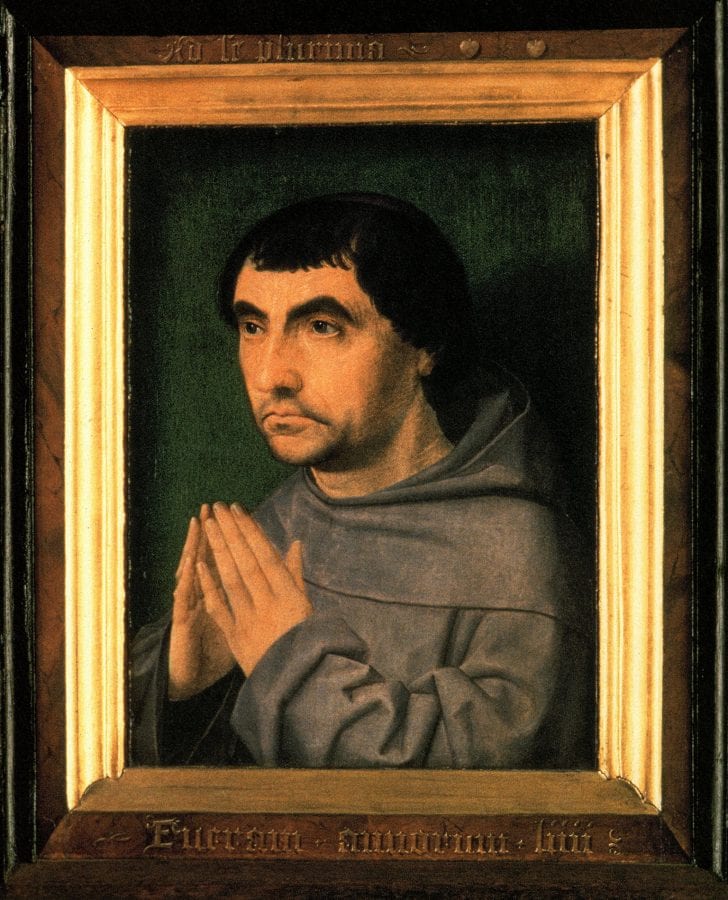

A related scenario occurs in Jan Provoost’s diptych of Christ Carrying the Cross from 1522 (fig. 14). The Franciscan patron in the left panel looks straight ahead, with the intent, albeit unfocused, gaze typical of visionary sight in Netherlandish painting.48 Christ, by contrast, looks purposefully at the votary portrait, his eyes angled downward, as if peering into the friar’s heart. That this diptych most fundamentally engages internal vision—“heart-to-heart” seeing—is made explicit by the two miniature hearts depicted along the upper edge of the donor panel. Together with a representation of a Franciscan cord on the top of the Christ panel, the hearts function as pictographs, accompanying painted words in an inscription reading, “Franciscan cords carry [or draw] the most hearts” (Francisci chorda traxit ad se plurima corda).49 Making a clever word play on the Latin chorda/corda,50 the painting implies an analogy between the knotted cord that recalls the Franciscan vows and the spiritual cord that binds the heart of Jesus to the heart of the friar. That emblematic rope is as steadfast as the lash that ties Christ’s hands and as unwavering as the intense gazes of the two figures.

Spiritual sight also operates as an organizing principle in the diptych of the Man of Sorrows and Georg, Count von Löwenstein, by the Bavarian artist Hans Pleydenwurff, circa 1456 (figs. 15 and 16). Here, the bleeding Christ turns dramatically to gaze down from his gilded and star-spangled aureole at the count in the adjoining panel. Like the Franciscan in Provoost’s diptych, Georg looks back toward Christ, but his blank stare, creased brow, and parted mouth indicate that the image before him is the vivid but noncorporeal product of his earnest prayers.51

Although the Atlanta-Chicago diptych exhibits similar internal seeing, it differs from the Pleydenwurff, Provoost, and Bouts panels in that it puts two narrative compositions in conversation with one another rather than two half-length, close-up figures already excised from the distractions of plot and setting. As a result, the introspective, “heart-to-heart” exchange between Christ and Mary across the frames is, at first, less apparent. Opening the diptych at an angle discloses the unexpected engagement between the Atlanta Christ and the Chicago Virgin and invites the viewer to use their interaction as a guide for pondering the images. In other words, votaries are to employ the same cycles of foresight, hindsight, memory, and emotional empathy used by Jesus and Mary as tools for discerning exegetical and devotional meaning in the Passion narrative.

The diptych provides specific examples of these cognitive processes. For instance, Christ interprets his own suffering typologically as he uses his fall to picture Mary’s collapse and his own expiration on Calvary. Suspended from the rood in the Chicago painting, the dead Jesus faces back toward the Atlanta panel, as if he had been recalling that dusty fall at the moment of its antitypical fulfillment, when he “gave up the ghost.”52 The Chicago Virgin’s memory of her son, huddled in the dirt like “a worm and no man,” layers an exegetical reading of the Psalms onto her eyewitness of his ignominious death. This memory—visualized by the Atlanta painting—also contains a recollection of herself prayerfully watching Christ along the Via dolorosa. The exacting nature of her observation is apparent by her fixed gaze, stoic face, and neatly positioned hands. Such rigorous, self-conscious gazing is afforded a special place in the Chicago Virgin’s memory because the images she sees become raw material for her to ponder, manipulate, and reassemble as she refashions herself in emulation of Christ. Her swoon beneath the cross, then, is not only a culminating expression of emotion but also an indicator of incisive cognitive exercise as she conforms her body to the mental image of her collapsed son.

In like manner, the diptych calls on viewers to look intently and self-consciously at the pendant images with heightened awareness that their methodical gazing could secure a devotional experience which circles back and forth in time and space, marshaling memory, exegetical interpretation, and imagination to achieve empathetic, “heart-to-heart” communion with the Lord and his sorrowful mother. Indeed, the votary’s multipart endeavor of looking ahead and behind, ascertaining type and antitype, and plumbing the affective depths of memory is itself an imitation of Christ and the Virgin. Having fallen to the ground in the depths of abject emotion, mother and son twist their minds forward and backward in conjunction with the shifting positions of their eyes, faces, and bodies. They join the viewer in looking up and ahead from the dirt of the Via dolorosa and down from Mount Calvary with panoramic hindsight.

A comparable exchange of typology and exegesis plays out between the narrative panels of another German Passion diptych (fig. 17). Dating to circa 1410 and conserved in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, the paintings depict a scene of Christ’s agony in the garden on the left and a Crucifixion on the right.53 Drops of blood streak the white garments of Christ as he kneels before a chalice, pleading with the Father to “let this cup pass.”54 Saints Peter, James, and John slumber beside him, despite the Lord’s exhortation to “watch and pray.”55 The left panel instigates the Passion, and the right panel concludes it, as the ominous cup of Gethsemane becomes two Eucharistic chalices held by angels attending at the cross. The Crucifixion, however, functions equally well as a rendering of Christ’s foresight, pictured in his mind’s eye as he meditates in the garden. As the Lord “in an agony . . . pray[s] more earnestly,” the triumph of his Passion takes shape in the adjoining panel, like a prophetic vision.56 He anticipates the completion of his suffering, when he would “bo[w] his head” and claim the relief of deathly sleep, analogous to the slumber of his three fatigued apostles.57 Conversely, the exhaustion of Saint John in the left panel—where he “sleep[s] for sorrow”—anticipates his acute and restless grief in the right-hand painting.58 There, he and Christ exchange roles as the evangelist atones for his careless dozing in Gethsemane by throwing back his hands and face to rivet his wakeful attention on the now-unconscious Jesus. Significantly, the stance of the swooning Virgin on Golgotha echoes the positions of the sleeping disciples in the left panel in order to contrast her Compassion with their sloth.

In the Atlanta-Chicago diptych, Mary’s manipulation of mental images inspires specific devotion to the face of Christ. As noted earlier, the Chicago Virgin turns away from the cross and lifts a segment of her veil with her left hand, perhaps to block the specter of her son’s corpse or to blot her eyes. The gesture draws attention to her face and, by extension, to the Holy Face of Jesus across from her, awash with tears and tactile streaks of blood. Raising the cloth to her cheek, Mary makes a sympathetic gesture to wipe the wounded head of her son, deeply emblazoned in her mind’s eye. The anguish of her memory has not only inspired her to emulate the compassionate ministration of Saint Veronica but to absorb the visage of Christ into her own countenance. Her pale face and the stark white of her immaculate veil contrast with the flushed and bloodied head of Christ, and yet the tears that brim from her watery blue eyes and collect in pools of bright highlights on her cheeks are consonant with the dripping face of her son. Significantly, tears no longer flow from the eyes of the crucified Christ, making the Virgin’s imitative weeping a function of her memory of the Via dolorosa, rather than of the present moment on Calvary. So pristine is the white fabric enveloping her fair skin that it prompts a phantom presence of bloody stains, implicit through the intensity of her empathy.59 This is especially so, given the red clothing worn by the figures on either side of Mary, which makes a dichotomous backdrop to her veil.

Images of the Mater dolorosa and other mourners with heads and hands veiled in white occur elsewhere in German art. The Mother of Sorrows from the Cummer Museum of Art, attributed to the Nuremberg-based Master of the Stötteritz Altarpeice and dated circa 1470, depicts a similarly dressed Virgin, the white material held in her hands and draped over her brow jarring dramatically with her bloodshot eyes and swollen face (fig. 18). As in the Chicago Crucifixion, it is not difficult to project blotches of red onto the white cloth. In fact, there is a well-known tradition of portraying the Virgin’s veil dotted with Christ’s blood, and in Germanic Pietà scenes Mary sometimes uses her mantle to dab at the wounds on her son’s broken body.60 In the Cummer Mother of Sorrows the Virgin’s tears, tinted pink from her reddened face, seem just as likely to stain her pure veil. David Areford further notes that the convention of cloth held in or wrapped around the Virgin’s hand implies a touching gesture and speaks to the Germanic fascination with Marian cloth relics during the fifteenth century.61 This association only bolsters the Chicago panel’s allusion to the most precious cloth relic in Christendom, as the Virgin’s imagination transforms the veil covering her head into the sudarium that wiped the Holy Face of her son.

Behind and to the right of the Chicago Virgin, Saint Mary Magdalene holds a handkerchief. Whereas Saint Veronica wiped the Lord’s face, the Magdalen anointed his feet, washed them with her tears, and dried them with her hair.62 Her hand, swathed in fabric, is imitative of the Virgin and is positioned directly below the side wound of the dead Christ, as if to stanch the blood flowing from his pierced heart down into the cloth wrapped about his waist. Unlike the other mourners, she has turned herself so completely toward Jesus that her face appears in strict profile. Her cloak overlaps the cross, and her handkerchief elides with the material worn by Christ. Poised between wiping away tears and wiping away blood, the Magdalen accentuates the Chicago Virgin’s exhortation for viewers to look upon the Lord’s countenance with such tearful, compassionate intensity that they could imaginatively extend their own hearts to the bleeding Christ and receive the image of the Holy Face imprinted on the fabric of their minds. In this way, they would share in Saint Veronica’s plea from the Passion play to receive Christ’s “great torture” “plant[ed] in [her] heart.”

This two-part, meditative endeavor in reaching out to the Lord’s wounded countenance and then taking a simulacrum of that countenance back in return is an extrapolation from the sequence of gestures made by these cloth-bearing women. The Magdalen extends her handkerchief away from her weeping eyes and toward the river of Christ’s blood. The Virgin, on the other hand, lifts her veil to her eyes, as if transferring the vera icona to her own face, as she relives her memory of the fallen Christ. Her movement reiterates the reality made explicit by the diptych’s circular interchanges of turning and gazing: that Christ’s image is already indelibly etched in the mind of his mother, as her image is in his.

Ultimately, the Atlanta and Chicago panels construe Holy Face devotion as an encounter in several different media: running with blood and tears, printed on the towel of Saint Veronica, reconfigured in the imagination, and rendered in pigments and gold on spruce planks covered in canvas and chalk ground. There exists yet another object in the diptych that, through its position, form, and medium, prompts meditation on the sudarium, albeit by counterfeit. On the right edge of the Chicago panel an armor-clad centurion stands among the group of officials endorsing Christ’s execution. His profile stance mimics the position of the Magdalen, but his helmet is pulled down over his eyes, and rather than holding a handkerchief, he balances a fanciful kite shield, probably made from brass and steel, and bearing a large, solar face.63 Such shields appear regularly in Passion scenes, their grimacing expressions parroting the cruelty of the soldiers and the barbarism of paganism. Within the devotional interchange of the Atlanta-Chicago diptych, however, this shield acquires a unique function. The disembodied head, with a ring in its mouth and surrounded by a mane of pointed, metal rays, evokes images of Christ, crowned with thorns and floating mystically above the folds of cloth on Saint Veronica’s veil. Although not shackled with a ring through his lip, the Atlanta Christ is led to his death by a rope, and the sharp tip at the bottom of the shield is reminiscent of the halberd prodding him along the road and the nails that would be driven through his hands and feet. The centurion’s grip on the shield even approximates the hand of the tormentor dragging Christ by the hair in the opposing panel, and they wear the same dark armor.64 Were it not for the gray mustache of the Atlanta figure, they could be mistaken for the same man, the Chicago soldier having traded back his fabric hat for his rightful helmet.

Likely alluding to a Roman deity, the molten effigy on the shield counterfeits the Christian God, whose cross and blood-stained body were envisioned as a protective shield in late medieval literature.65 Unlike the sudarium, the pagan shield is the product of human artifice, its metal contours as hard and unresponsive as the features of an idol. On the other hand, the constitution of the Holy Face is delicate and supple—the cloth, flesh, sweat, blood, wood, and paint bodying forth the incarnate God who substituted “fleshy tables of the heart” for the Mosaic tablets of stone.66 Given the fundamental role of spiritual and corporeal sight in apprehending the Holy Face, it is significant that the soldier holding the shield is blinded by the impenetrable visor of his helmet.67 The eyes of the solar head are themselves turned emphatically to the right, as if straining not to see the true “shield” for all Christians, hanging from the cross. Like an echo of the heathen idols that plummeted from their altars at the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt, the head anticipates the fall of paganism as another antitype of Christ’s fall on the Via dolorosa. Its refusal to look is made particularly blatant by the Jewish elder just to the left who points to Christ. As the antithesis of the weeping Virgin, the impassive face pivots away from the hinged threshold between the two panels, across which the diptych’s interchange of empathy, memory, and prophecy occurs.

It is that liminal border between the Atlanta and Chicago paintings where viewers could join Christ and the Virgin in their circular exchange of compassion. The diptych calls for attentive looking, whether set up on a table or held close to the face, like an open book. The meditative images votaries would transfer from the canvas-covered panels to the “fabric” of their minds would constitute a kind of internal sudarium. Like their historical prototype, these memories would take shape “without hands,” from the tears and sweat of personal compunction, propelled by the violence of the Atlanta panel’s tormentors and the sharpness of the Lord’s thorny crown. Having printed his countenance in their minds, viewers could then look away from the diptych like the Chicago Virgin, who shields her eyes from her crucified son, and yet never lose eye contact with the anguished face of Christ staring out of their hearts.