Comparing cross-sections to treatises and recipe books, pictorial representations, and descriptions of unfinished paintings, this paper reassesses the early rise of colored grounds in central France from the Romanesque era, first in wall paintings and then in easel paintings. It examines their spread in relation to the availability of earth pigments and to style. The desire to achieve chiaroscuro effects may have fostered their development, and this practice was then adopted by some Netherlandish courtly painters active in France by the end of the fourteenth century, long before the arrival of Italian artists at Fontainebleau, who were previously considered responsible for the introduction of colored grounds.

The history of colored grounds in Netherlandish painting has long been told as a story that begins in northern Italy, from where the practice spread northward in the sixteenth century. The idea of a French connection for colored ground layers in the Netherlands, in particular the School of Fontainebleau as an early source, was first suggested in 1979 by Hessel Miedema and Bert Meijer, who noted the presence of colored grounds in pictures by Abraham Bloemaert, Cornelis Ketel, and Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem on their return from France in the early 1580s.1 The recent gathering of scientific analysis documenting the painting techniques of Old Masters active in France, however, reveals earlier and previously unrecognized examples, some dating back to the Romanesque period. This article reconsiders both the chronology and the mechanisms by which colored grounds were transmitted and the implications of these new findings from France for the study of Netherlandish painting.

This article’s main technical findings derive from pigment cross-sections, most taken during conservation treatment. By comparing the ground layers that are visible in cross-sections to discussions of grounds in treatises and recipe books—and to the visual evidence of grounds in pictorial representations and archival descriptions of unfinished paintings—this article reassesses the development of colored grounds in central France from their early rise in wall paintings in the eleventh century until their use in easel paintings, beginning at least in the late fourteenth century. It examines their spread throughout France until the beginning of the seventeenth century, in relation both to the availability of the earth pigments that were used to make colored ground and to stylistic developments that rely on colored grounds. The desire to achieve chiaroscuro effects may have encouraged the development of colored grounds. This approach was then adopted by some Netherlandish courtly painters working in France from the late fourteenth century, well before the arrival of Italian artists at Fontainebleau, who were long credited with introducing the practice.

The study builds on and expands earlier technical scholarship on French painting. Alain Duval’s pioneering work in 1992 analyzed 155 cases from the 1630s to the late eighteenth century.2 His colleague Élisabeth Martin extended his research in 2000 and identified a technical turn around 1615, marked by the adoption of red-brown grounds across multiple artistic centers.3 Examining a group of one hundred French, Italian, and Flemish paintings from French museum collections dating between about 1600 and 1640, she grouped the works into six categories based on the predominant color of the ground (including white) and its main component: chalk, earth pigments, or lead white.4 More recently, in her thorough study of preparatory layers in European oil paintings from 1550 to 1900 (2017), Maartje Stols-Witlox classified various ground layer recipes according to the painting support and included an important, recently rediscovered sixteenth-century French source, Ms. Fr. 640 from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.5 Following the suggestion of Miedema and Meijer, Laura Pichard focused on the influence of Italian artists at Fontainebleau in her master’s thesis (2020) about grounds in easel paintings made in France at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.6 She suggested that Nicolò dell’Abate, who worked at the French court from 1552 until his death in 1571, may have played a significant part in the introduction of colored grounds into French painting.

Indeed, until now, the use of colored grounds in European painting was thought to have originated in Northern Italy, in the work of Dosso Dossi and Correggio in the Po valley—and perhaps even as early as Carlo Crivelli’s 1470 Madonna, which is on a yellow ocher ground.7 However, the French evidence points to a more complex and earlier history. It appears that Romanesque and Gothic painters in France were already employing colored grounds centuries before the Italian examples that are traditionally cited as a point of origin. Their broader adoption was part of a complex process involving artists from various regions, including the Netherlands.

Until the 1630s, most French paintings were prepared with white grounds, usually made of chalk and glue (resembling Netherlandish panel grounds) or gypsum and glue in Provence (similar to Italian gesso).8 Yet at least forty-six paintings with colored grounds produced in France before 1610 have now been identified. Most have been studied in conservation laboratories and sometimes published as case studies.9 These examples challenge the traditional narrative of an exclusively Italian origin for colored grounds. This special issue, guest edited by Maartje Stols-Witlox and Elmer Kolfin from the Down to the Ground project, provides an opportunity to synthesize this evidence and to investigate how colored grounds emerged and spread in and beyond France, which painters employed them, and for what purposes. To establish the chronology of the spread, this article focuses on well-characterized cases supported by scientific analysis (Table 1). To explain the function of colored grounds and discuss questions of authorship, it also draws on recipes and documentary sources—including two manuscripts newly published since 2020—as well as the visual examination of artworks.10

A Chronology of the Spread

Colored grounds cannot be studied properly without taking both wall and easel paintings into account, since the same artists often practiced both techniques.11 Wall paintings also provide the geographical framework necessary to understand the dynamics of the spread of colored grounds and to put the scarce early panels in context. Judging from surviving artworks, the rise of colored grounds in French painting appears to have begun in the Loire valley as early as the twelfth century.

Colored Grounds: A Precocious French Specialty (ca. 1100–1400)

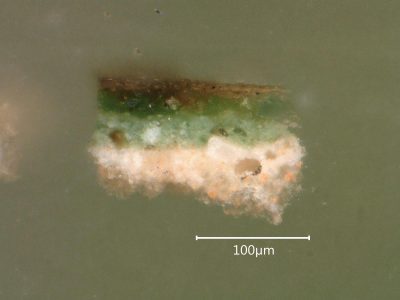

The earliest known red-brown grounds seem to have been experimental layers in frescoes. Red-brown underlayers have been found locally under ultramarine blue in the Miraculous Draught of Fishes, in the chapter room of Trinity Abbey in Vendôme (Loir-et-Cher) (figs. 1 and 2), and under entire painted surfaces in nearby churches at Lavardin and Saint-Jacques-des-Guérets, as well as further south at Nohant-Vic (Indre), all from the twelfth century.12 Around the same period in Brioude (Haute-Loire), a dark gray ground made of carbon black was applied to the Last Judgment fresco in the basilica of Saint-Julien.13

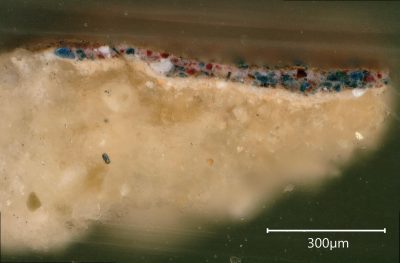

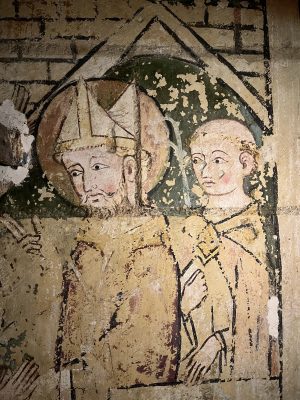

In Anjou, colored grounds were used almost continuously from the thirteenth century until the Renaissance, along with a new medium: oil. Around 1246–1250, a red-brown ground was used under the false-stone decoration of the Ronceray Abbey Church in Angers, one of the oldest preserved oil paintings in France.14 From the next generation (ca. 1270–1280), the Story of Saint Maurille, a thirty-meter-long wall painting in the apse of Angers Cathedral, now hidden behind eighteenth-century wood paneling, shows evidence of several painting techniques (fig. 3).15 One of the painters worked on a colored ground made of chalk, sand, and a little red lead (figs. 4 and 5).

Around the same time, the Saint George chapel in the Clermont-Ferrand Cathedral in Auvergne was adorned with scenes from the saint’s life in distemper on a light orange ground containing red lead.16 Nearby, a frieze of six canons and other clerks from the De Jeu family presented by an angel (ca. 1275–1302) was painted over a red-brown ground.17 The presence of multiple ground colors in both the Loire valley and Auvergne during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries suggests the practice was more widespread than previously assumed.18

Yellow ocher grounds seem to have appeared a little later and were common in fourteenth-century northwestern France, as the Liber de coloribus illuminorum sive pictorum, an Anglo-Norman treatise on painting (ca. 1300–1340), testifies.19 In the Crucifixion from the same period in the Bayeux Cathedral treasure room, a yellow ocher layer was applied over the standard white chalk and glue ground.20 Yellow grounds frequently accompanied vermilion backgrounds, particularly in the International Gothic style, as in the Angels Playing Instruments (ca. 1367–1385) on the vaults of the Virgin Mary chapel in Le Mans Cathedral, attributed to Jan Boudolf (act. 1368–1381) from Bruges.21 By the end of the fourteenth century, colored grounds had also reached Burgundy, as seen in the yellow ocher ground of the wall paintings at Germolles Castle in Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire), painted around 1389–1390 by Jean de Beaumetz (ca. 1335–1396).22

Spreading to Easel Painting and Most French Provinces (ca. 1400–ca. 1530)

Only after three centuries of use in wall painting do we find surviving examples of colored grounds on panels, although the third book of Heraclius’s De coloribus et artibus Romanorum confirms that they already existed in thirteenth-century France.23 Dating to about 1390 to 1400, two wings from an altarpiece showing saints on red backgrounds in the Angers Museum of Fine Arts reveal a brown preparatory layer (fig. 6 ).24 Around 1410, cantor Pierre de Wissant commissioned a triptych for his chapel in Laon Cathedral (Aisne). The left wing, depicting the Angel Gabriel with Mary Magdalen introducing the donor (fig. 7 inside and fig. 7 outside), was prepared with two layers containing yellow ocher (figs. 8 and 9).25 Recent analysis of the oldest known oil painting on canvas in France, the Virgin and Child with Butterflies, most likely painted in Burgundy around 1415 by Johan Maelwael (1370–1415) or Henri Bellechose (died 1440), revealed a yellow ground of chalk and yellow ocher.26

In Angers Cathedral, the tomb decoration for Louis II of Anjou (ca. 1425–1450) also used a yellow ground, but here the paint layers were bound with gum lac.27 The same binder and ground color appear in the chapel of Montreuil-Bellay Castle (Maine-et-Loire), around 1480–1485, whose wall paintings depict saints and angels surrounding the Crucifixion. They are usually attributed to Coppin Delf (1456–1482), a Netherlandish painter from Delft in the service of Duke René d’Anjou.28

Along with the new Eyckian style coming from the Low Countries in the 1430s, a taste for illusionism appeared in Western Europe, and painters strove for a more exact imitation of nature, human complexions, and the sheen of luxurious materials like fabric or gold. This approach relied on the use of a white ground combined with transparent layers of both oil and varnishes.29 While most French artists, including Jean Fouquet, followed this trend, the traditional Loire valley recipe for a yellow ocher ground persisted, as, for example, in the altarpiece for the Saint Hippolyte Priory in Vivoin, near Le Mans (figs. 10, 11, 12, and 13). Around 1480–1490, the Master of the Beaussant Altarpiece, perhaps Pierre Garnier, also used a yellow ground.30

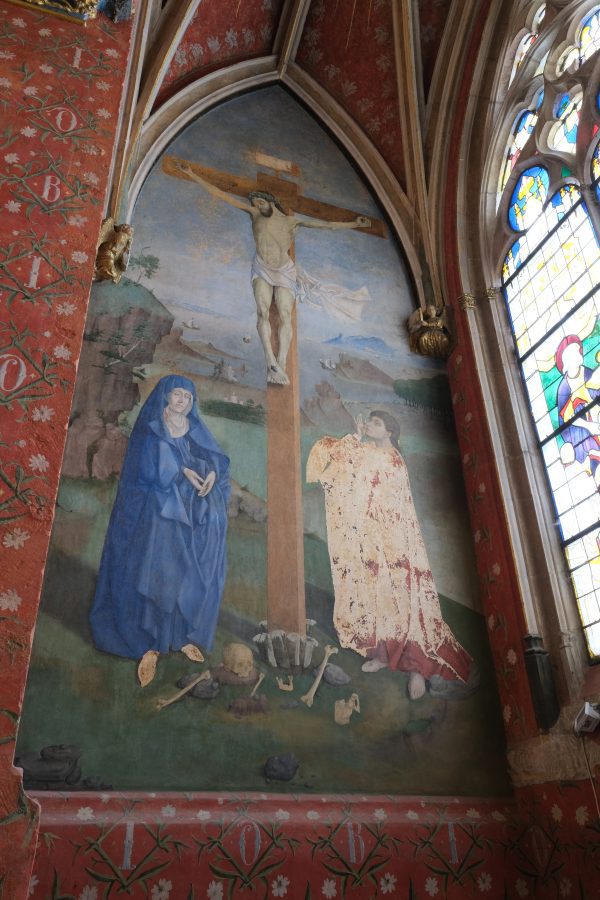

In the later fifteenth century, yellow grounds continued being used in Burgundian wall paintings. This can be seen in the Crucifixion in Notre-Dame Church, Dijon (after 1472); the Tree of Jesse at the Church of Saint-Bris-le-Vineux (1500); and the Passion of Christ in the Saint-Anne chapel, Saint-Fargeau cemetery, Yonne (ca. 1502).31 From the Loire valley, the technique was also in use further west; the Baptism of Christ in Saint-Mélaine, Rennes (ca. 1460–1470) is painted on a yellow ground.32 Conservator Geraldine Fray identified similar yellow grounds in several wall paintings commissioned by the Rohan family in southern Brittany around 1500.33

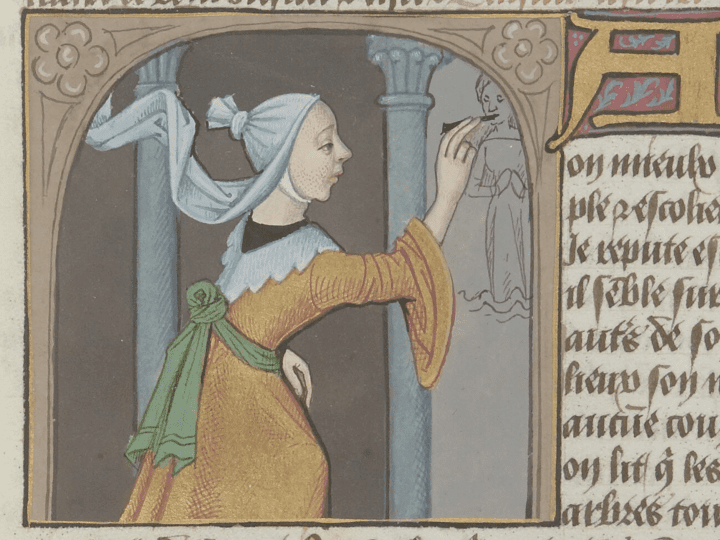

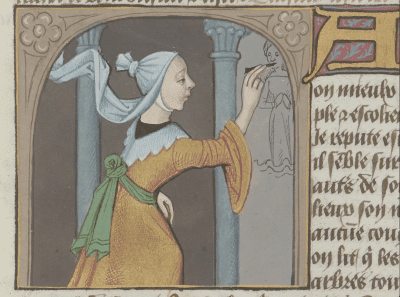

The mid-fifteenth century saw a revival of the gray grounds seen in twelfth- and thirteenth-century frescoes. The Netherlandish painter Barthélemy d’Eyck used this color in his Annunciation (fig. 14) while working in Aix-en-Provence under the patronage of Duke René of Anjou.34 A gray ground has also been found in the chapel at Hôtel Jacques Cœur in Bourges (ca. 1450), whose angels are attributed to Jacob de Litemont (d. ca. 1474), another Netherlandish artist, active at the court of King Charles VII.35 Around 1475, a dark gray ground was applied to the Seven Liberal Arts fresco in Le Puy-en-Velay Cathedral (Haute-Loire), recently attributed to the Spanish master Pedro Berruguete.36 And in his depiction of the ancient Greek painter Irene from Boccaccio’s On Famous Women, Robinet Testard depicted her making a black underdrawing over a gray ground (fig. 15). The manuscript must have been illuminated in Cognac (Charente) between 1488 and 1496.37

In 1506, the Master of Antoine Clabault, perhaps Riquier Haurroye, painted sibyls in a chapel of Amiens Cathedral with a double-colored ground: yellow ocher on top of white chalk and red lead.38 Thus, even before the arrival of Italian artists at Fontainebleau in 1530, the full range of colored grounds familiar to scholars of the seventeenth century—red-brown, orange, yellow, gray, and double-colored—had already been used in French paintings, on various supports, for generations.

Colored Grounds and the School of Fontainebleau (ca. 1530–ca. 1610)

When Rosso Fiorentino was invited to join the court of King Francis I in 1530, he designed frescoes for the main gallery of the Château de Fontainebleau and delivered a monumental depiction of Bacchus, Venus and Cupid. It was once an oval canvas, glued to panel and set among stucco ornamentation at the eastern end of the gallery. The painting has a white lead and oil ground beneath a dark gray second ground, now visible in the worn shadows of the gods’ naked bodies.39 Rosso’s Pietà for the Montmorency family (ca. 1530–1540) has a dark gray ground, used both to suggest the tomb in the background and to cover an earlier composition that the painter reworked.40 Its white first ground was partially lost when the paint layers were transferred from panel to canvas.41

Very few paintings with colored grounds survive from the 1530s to the 1550s, which may explain why researchers did not think to survey the previous centuries. Yellow ocher grounds continued in Burgundy into the sixteenth century, as, for instance, in the Church of Chambolle-Musigny, which has inscriptions dating from 1534 to 1539.42 By midcentury, the new Fontainebleau style often blended with traditional French techniques. Italian masters were often asked for designs, while the execution could be divided among Italian and French assistants, hence the label ‟School of Fontainebleau.”43 Three midcentury cases are especially relevant for their colored grounds and clear awareness of Fontainebleau stylistic innovations: the Story of Troy wall paintings at Château d’Oiron (Deux-Sèvres; ca. 1546–1549; fig. 16), the mantelpieces of Château d’Écouen (Val d’Oise; ca. 1550), and a panel from Amiens attributed to Geoffroy Dumonstier from Rouen, who came to Fontainebleau in the late 1530s. At Oiron, the wall was first covered with casein-based mortar, and then a red ocher ground was applied underneath the oil layers (fig. 17).44 At Écouen, the mantelpieces were painted with a mixture of oil and resin on a light orange ground of yellow ocher on limestone.45 Cross-sections from the Queen of Sheba mantelpiece (fig. 18) revealed a gray layer over the yellow ground (figs. 19 and 20). The Amiens panel, Exquisite Triumph of the Faithful Knight (1549), has a red lead and red earth ground that is visible at the limit of the painted surface in the curved upper part (fig. 21).46

When Nicolò dell’Abate from Modena arrived at the French court in 1552, his compatriot Dosso Dossi had already been using red-brown grounds in Ferrara for several years. Laura Pichard proposed that Nicolò introduced this practice into French painting, pointing to a landscape attributed to his circle, possibly by his son Giulio Camillo dell’Abate, with a red-brown ground (fig. 22 ).47 Yet pigment analysis shows that these red-brown grounds were not necessarily the norm for Italian painters at Fontainebleau. Certain paintings securely attributed to Nicolò’s French period, such as the Continence of Scipio and Pandora (Musée du Louvre), are painted on a white ground. The Death of Eurydice in the National Gallery of London has a white gesso first ground with a gray second ground.48 Another Italian artist, Ruggiero de Ruggieri from Bologna, did not use a red-brown ground for his 1569 copies of Primaticcio’s Story of Ulysses; his Ulysses Protected from Circe’s Charms, now in Fontainebleau, has white ground containing bits of red lead.49

While Jean and François Clouet employed white chalk grounds, their imitators started using colored grounds. The anonymous Lady at Her Toilette (Dijon Museum of Fine Arts), probably made in Paris or Tours around 1560, has a white chalk ground with particles of red and black pigments.50 A Lady at Her Bath, after François Clouet, has two gray ground layers, the first light gray and the second dark gray (fig. 23).51 Since this is a copy after the famous panel at the National Gallery in Washington, DC, it is hard to date precisely, but it was likely made between 1571 and 1610. Around 1580–1590, an unknown artist painted The Woman Between the Two Ages on a red-brown ground (fig. 24). The painter seems familiar with the art of François Clouet and was likely active in Paris; if not Nicolas Leblond himself, he must have worked in his circle.52 Another picture from this decade, the anonymous Ball on Occasion of the Duke of Joyeuse’s Wedding (ca. 1581), has a gray ground.53

From the end of the sixteenth century, there seems to have been a decline in yellow ocher grounds, though they do still appear, as in the Portrait of a Man (1593, Reims Museum of Fine Arts) attributed to Flemish artist Joris Boba.54 Gray grounds became common in the Second School of Fontainebleau, under the reign of Henry IV (1589–1610). In 1596, the probate inventory of Toussaint Dubreuil’s wife described an unfinished picture in his Paris workshop as “primed with gray.”55 His fellow painter Ambrosius Bosschaert (Ambroise Dubois) also used gray for his ground in Allegory of Painting, painted on canvas around 1600 for the Cabinet de la Volière at Fontainebleau.56

A notable variation, the double-colored ground—yellow ocher on top of white chalk and red lead—already seen at Amiens in 1506 and Écouen around 1550, appears in Vertumnus and Pomona, once attributed to Toussaint Dubreuil but perhaps a copy after Nicolò dell’Abate (ca. 1580–1600; Louvre).57 The anonymous Venus Mourning Adonis (ca. 1600–1610; Louvre),58 Ambrosius Bosschaert’s Chariclea Nursing the Wounded Theagenes (ca. 1600–1605; château de Fontainebleau),59 and the Last Judgment by Jacques Le Pileur (fig. 25) also have double-colored grounds (figs. 26 and 27).60

The evidence shows that colored grounds—especially yellow ocher and red grounds—have a very long history in French wall painting, and that from at least the fourteenth century they were also used in easel painting, on panel as well as canvas. The arrival of Italian artists at Fontainebleau in 1530 played only a limited role in disseminating the technique. Red-brown grounds were mainly used in court painting under Henry III (1574–1589), while double-colored grounds gained popularity in the Second School of Fontainebleau under Henry IV, though earlier examples are known from the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Ground Color Recipes, Pictorial Effects, and Authorship Issues

For each main ground color used around 1600 described by Élisabeth Martin, we now have examples in French paintings before 1500.61 Moreover, a survey of medieval and early modern French technical literature reveals recipes for all these grounds. While these sources often suggest specific ground recipes for specific painting supports, analysis shows that artists experimented with different combinations of binding media and supports, as trade regulations allowed. Most painters working in France had a versatile practice, including ephemeral decorations for celebrations; easel paintings in oil, glue, or tempera; book illumination; wall paintings; polychromy; and sometimes even stained glass or ceramics.62 Colored grounds could be a timesaving way to achieve pictorial effects, especially chiaroscuro.

Red-Brown Grounds

Red-brown grounds for paintings are as old as the Romanesque era. Although they may seem strange in frescoes, since lime-bound paint layers are not translucent, examples such as those in Vendôme show a red ocher ground under ultramarine, likely to create a purple tone from a distance (see fig. 1 and fig. 2). The painter clearly worked from dark to light: on a pink flesh tone, he painted the faces of his figures using red ocher for the main features, green earth in the shadows, and white highlights. At Saint-Jacques-des-Guérets, however, the purpose of the full red-brown ground under a white background remains unclear—though ocher could have served as a sealer for porous stones.

From the thirteenth century, red-brown grounds were used in oil wall paintings, as in Ronceray Abbey in Angers, and on panels, such as the Angers Museum altarpiece wings (ca. 1390), where the ground complements a vermilion background (see fig. 6). A recipe for such red grounds on wood was collected by Jean Lebègue in 1431: ‟If you wish to redden tables or other things. Take linseed, or hemp-seed, or nut-oil and mix it with minium or cinople on a stone without water; then with a pencil, illuminate what you wish to redden with this.”63 Here ‟Cynople” or ‟sinople” referred to red earth or hematite, originally coming from Sinop, Turkey. More famous under its Italian name, sinopia, the word, in French context, could also mean a red lake pigment.

After a gap of a century and a half, another red ocher ground appears at Château d’Oiron (see figs. 16 and 17). The attribution of the gallery of the Story of Troy has been much discussed. A now-lost notarial document recorded that a painter called Noël Jallier was paid for painting fourteen scenes at Oiron in 1550; however, the Louvre recently acquired a preparatory drawing for one of them, the Sacrifice of Iphigenia, and curators noted its many Italian influences.64 Conservation analysis shows that the wall was first covered with casein-based mortar and then a red ocher ground beneath the oil paint layers, evidence that supports its production by a French workshop, possibly following Italian designs.65 If Jallier is the author of the compositions, which indeed cite Roman and Florentine motifs, he may also have traveled to Italy himself.66 The Horse of Troy is in better condition than many of the other scenes and displays elaborate light effects in the naked bodies and in the soldier standing by the frame on the right-hand side, whose breastplate is highlighted with pure lead-tin yellow.

Red-brown grounds became widespread in France from the 1580s, with the growing taste for chiaroscuro. Even before Caravaggio, French aristocrats started collecting religious compositions and genre scenes with night effects made by Jacopo Bassano, and later his sons Francesco and Leandro. At the Saint-Germain-des-Prés fair around 1600, merchant painters such as Nicolas Baullery, Nicolas Leblond, and Moïse Bougault would sell serial copies in the manner of the Bassano family.67Another Frenchman, Jacob Bunel, a painter from Blois, also contributed to this trend.68 His Flute Player, now in the Louvre, bears a handwritten inscription at the back of the canvas that has been read ‟Giacomo Bunel F.[ecit] 1591 Venetia.” The same character also appears in larger concert scenes displaying an obvious Venetian inspiration.69 An anonymous Vision of Constantine (ca. 1600; Château d’Azay-le-Rideau) possibly from his circle associates a twill canvas—another Venetian trend of the time—with a red-brown ground.70 Caravaggio’s friend, painter and art dealer Lodewijk Finson, probably helped spread the technique during his stay in Provence (1613–1614) on his way back from Rome. During the first half of the seventeenth century, under the effects of a developing art market, painting techniques in France tended toward oil on canvas atop a colored ground.

Technical analysis mostly reveals the use of red ocher and hematite, sometimes umber and clay, for these red-brown grounds.71 Pierre Lebrun’s Recueuil des essay des merveilles de la peinture (1635) also mentions “potter’s earth” among possible ingredients for red-brown grounds: “The canvases are covered with parchment glue or flour paste before they are primed with potter’s earth, yellow earth or ocher ground with linseed or nut oil. The priming is laid on the canvas with the knife or amassette to render it smoother, and this is the work of the boy.”72

Orange Grounds

In the Middle Ages, the color that we call orange had no specific name and was considered a red hue. In manuscripts, a title painted in red (rubrica) could be made either of vermilion or red lead. Two main groups of orange grounds are found in paintings as well as recipes: a light orange, made from a mixture of red lead and white, and a darker, stronger version based on red lead. In the thirteenth century, the third book of Heraclius provided a recipe for the first type on panels, advising a preparation of lead white, wax, and ground bricks.73 A similar light orange has been identified in late thirteenth-century oil paintings on walls at Angers Cathedral, where the brick was replaced with tiny bits of red lead mixed with chalk and sand. The result proved unsatisfactory, as flaking is evident in these areas (see fig. 3). Elsewhere, the same painter used a lead white ground, and the paintings remain in much better condition. As Marie Pasquine Subes-Picot noted, this type of white and red lead ground has been found in the wall paintings of Saint Stephen Chapel in Westminster Abbey (ca. 1300), now in the British Museum, London.74 Although their styles are quite different, a similar technique was being used on both sides of the English Channel, where the lands were ruled by the House of Plantagenet. Moreover, in 1301 the Earl of Artois’s accounts record the purchase of one hundred pounds each of red lead and white to prime the new addition to the chapel at Hesdin Castle.75 A seventeenth-century manuscript from Orléans also records this composition, recommending it as a double-colored ground for wall paintings.76 As noted earlier, this practice had been transferred to easel painting by at least the sixteenth century.

A darker shade of orange, mostly made of red lead, also seems to have been tried. As mentioned above, Jean Lebègue gave a recipe to ‟redden” panels with red lead and oil. An example of this red lead (with red earth) priming can be seen on a panel titled Exquisite Triumph of the Faithful Knight, commissioned to adorn Amiens Cathedral in 1549 (see fig. 21).77 Contrary to other “Puy d’Amiens” panels, this work retains its original support, with the barbe still visible at the paint edges. The recent attribution to Geoffroy Dumonstier remains debated.78 From a distance, the group portrait in the foreground resembles the art of Corneille de Lyon, yet the flesh tones of the characters are based on an opaque pink layer modeled with brown glazes, whereas Corneille preferred a white ground that allowed the light to shine through the complexion. Dumonstier employed such layering in some of his miniatures, including a portrait. The only other painting known so far with this red lead first layer was commissioned in 1604 from Jacques Le Pileur, who trained in Rouen like Dumonstier.79 Red lead was available either from lead mines in the Armorican Massif in northwestern France or imported from Britain, and its siccative properties in oil painting were well known to artists.80

Yellow Grounds

Yellow grounds were usually made of yellow ocher and used for wall paintings, as noted in Liber de coloribus illuminatorum sive pictorum from Sloane Ms. 1754, a treatise on illumination and painting from about 1300–1340: “But you must know that ocher is needed only by painters of mural-decorations, except that, when you wish to make a letter of gold, you lay it in first with fine ocher and gypsum.”81 According to the same source, yellow ocher was abundant in the Loire valley in the Middle Ages, and its quality was especially prized: “There is also another yellow from a different shade, called ocher, and it is found in many places; but that which is brought from the city of Tours is more desirable than the others.”82 Important yellow ocher quarries were located in Saint-Georges-sur-la-Prée (Cher); from there, pigment was shipped in barrels down the river Cher and stored in Tours.83 Red (or burnt) ocher found in other northwestern and Auvergne paintings may have the same origin. The Puisaye area, west of Auxerre in Burgundy, also contained yellow ocher deposits, though whether they were mined in this period remains uncertain. In 1390, when Jean de Beaumetz was decorating the castle of Germolles for the Duchess of Burgundy, he was supplied with “ocre de Berry,” not local ocher.84 Yellow ocher was sometimes combined with lead-based pigments, used both for their tone and drying properties. In the Baptism of Christ from the Church of Saint-Mélaine in Rennes (ca. 1460–1470), the oil painting is on a ground of yellow ocher and lead-tin yellow, determined both by cross-sections and laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS).85 The popularity of these yellow ocher grounds in French wall paintings is unexplained, though they provided a warm tone to build on and were often associated with vermilion backgrounds. In the Last Judgment from Ennezat (Puy-de-Dôme), dated 1405, the painter went a step further, working from dark to light in multiple layers and leaving parts of the yellow ocher layer visible (fig. 28).86

Four examples of wall paintings with yellow grounds have been attributed to Netherlandish court artists: Jan Boudolf in Le Mans Cathedral (ca. 1367–1385);87 Jacob de Litemont in the Hôtel Jacques Coeur’s chapel in Bourges (ca. 1450);88 an anonymous painter of the Crucifixion and Noli me tangere wall paintings in the Breuil Chapel in Bourges Cathedral (figs. 29 and 30);89 and Coppin Delf in the chapel of Montreuil-Bellay castle (Maine-et-Loire; ca. 1480–1485). The French court’s presence in these areas during the fourteenth, fifteenth, and early sixteenth centuries likely exposed these foreign artists to local users of colored grounds. In Bourges Cathedral, the painter may not have been familiar with yellow grounds, since his upper layers of drapery flaked away due to insufficient adhesion, revealing the ground underneath. The likeliest identity for this painter is Henri de Vulcop, from Vuijlcop in the Netherlands (now in the town of Houten near Utrecht), who was still active in Bourges in 1472 and died before 1479.90

Cross-cultural exchanges continued with the Italian Wars (1494–1559), this time with Italian artists. Around 1500, the chapel walls of the Hôtel de Cluny in Paris, once the Parisian home of the Abbots of Cluny in Burgundy, depicts Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome mourning the dead Christ in a carved Descent from the Cross, no longer in place. Timothy Verdon attributed the project to the Italian sculptor Guido Mazzoni da Modena, who is known to have worked for members of the Amboise family, here Jacques d’Amboise, Abbot of Cluny.91 The paint layers are applied on a pink ground, mostly made of yellow ocher.92 The attribution of the wall paintings to Mazzoni has been criticized by François Avril, who made interesting comparisons to contemporaneous manuscripts from Burgundy.93 Indeed, the motifs are Italianate (putti, garlands, shells, etc.) and the female saints look monumental, as Mazzoni’s carved characters did, but the technique may well support the idea of an Italian design executed by a French artist.

The traditional Loire valley yellow ground for wall paintings persisted into the seventeenth century. Sebastien de Saint-Aignan’s treatise on painting titled The Second Nature (Orléans, 1644) advises: “After the walls are prepared with lime and sand, you need to soak them with siccative oil, or common oil with a bit of ocher and red lead to dry it.”94 The author advised painting on walls as little as possible, as wall paintings would flake away and a white veil could appear with age—as seen, for instance, in Amiens Cathedral or Château d’Oiron. This veil might be related to the use of organic materials in the mortar, for which Saint-Aignan also provided a recipe made of chalk, sand, and lanolin rather than casein. Although he was not a professional painter, the fact that he combined old-fashioned, local knowledge with a more up-to-date recipe for canvas painting makes his testimony valuable.95

By the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, artists had begun using yellow preparations for easel paintings. Johan Maelwael (or Henri Bellechose?) may have adapted Jean de Beaumetz’s wall painting technique in the Berlin Virgin and Child with Butterflies (ca. 1415; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin).96 The Master of Vivoin mixed yellow ocher and red lead to prepare the panels of his Saint Hippolyte Triptych (ca. 1460; Tessé Museum, Le Mans), while the Laon panel painter (see figs. 7 (inside) and 7 (outside)) used yellow ocher and lead white.97 Colart de Laon, an artist mostly active in Paris in the service of King Charles VI and Duke Louis of Orleans, may have introduced this practice into Picardy.98 Although the Master of Vivoin shows a visual knowledge of Netherlandish art in his atmospheric perspective and rendering of fabric, using lead-tin yellow highlights for gold embroidery, he employed a red lead and yellow ocher ground that is fully covered with paint layers. Charles Sterling proposed to identify him as a local artist around 1460.99

A French recipe book from about 1580, claiming information from Parisian painter Jean Cousin the Younger, records a yellow-tinted ground using stil de grain yellow to prime panels.100 A few pages later, the author suggests lead white, yellow ocher, and a little lead-tin yellow: “It is good to do it with ceruse, yellow ocher, and a little massicot, and make it not very thick in order that it does not crack.”101 This source confirms that yellow grounds must have been more common than historians have long thought, even in easel painting. Pierre Lebrun’s later recipe for red-brown grounds also included yellow ocher, indicating a wide range of personal mixtures.

Gray Grounds

Gray grounds were usually made of carbon black and lead white or chalk, with hues ranging from light gray to nearly black. Apart from one Romanesque fresco in Brioude, they appear mainly in paintings from the fifteenth century on, as in a miniature by Robinet Testard (fig. 31).

Recipes for gray grounds were often more elaborate than just blending black and white pigments. Saint-Aignan (1644) describes a mixture of sheep bone black, charcoal, umber, and red lead.102 Several sources mention or couleur (color for gold), a gray mixture of old oil and pigments from the brush-cleaning pot that was commonly used as a size layer for oil gilding, hence its name. The recently published French manuscript from the sixteenth century, BnF Ms. Fr. 640, warns that one should avoid including corrosive pigments such as verdigris into this mixture.103 Pierre Lebrun does not include this warning: “The pinceliere is a vase in which the brushes are cleaned with oil, and of the mixture of oil and dirty colors is made a gray color, useful for certain purposes, such as to lay on the first coats, or to prime the canvas.”104 Saint-Aignan also refers to this practice.105

Ashes were another readily available material. The author of Ms. Français 640 recommends using them to make a light gray suitable for both panels and canvas. For panels, the author recommends common ashes with oil to eliminate irregularities in the wood.106 As for canvas: “In a painting in oil on canvas, one applies only one preparatory layer, and the same ashes can be used there.”107

While such grounds are difficult to identify through technical analysis, their pictorial effects are evident in the works of two Netherlandish painters active in France in the mid-fifteenth century: Barthélemy d’Eyck and Jacob de Litemont. In the Aix Annunciation (see fig. 14), cross-sections taken in 1993 by Johan Rudolf Justus Van Asperen de Boer revealed a gray ground.108 Barthélemy d’Eyck used it as a midtone in the faces and in the architectural background, harmonizing with the setting of a church nave with monochrome statues, and enhanced it with glazes to suggest light on stone and to heighten the trompe-l’œil effect. The Holy Family from Le Puy-en-Velay, attributed to this master by Nicole Reynaud, shows a similar approach on canvas (fig. 32 ).109 Worn passages in the faces reveal a gray layer beneath the paint, although without cross- sections it is uncertain whether it is the same gray ground as the Aix painting. This ambiguity also applies to the 1456 Portrait of a Man on parchment in the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein, again attributed to Barthélemy d’Eyck, which also has a dark gray layer under the sitter’s complexion. Manuscripts illuminated by the master in his maturity, such as the Livre du Cœur d’amour épris (ca. 1460–1469; Austrian National Library) display virtuoso use of gray brushwork for modeling, raising questions about where and how the artist learned this technique.110

Jacob de Litemont also used a gray preparation in the Hôtel Jacques Cœur chapel in Bourges (ca. 1450). While most of the vault in the chapel is painted on a yellow ground, areas with a blue background sit atop a gray one, according to the cross- sections analyzed by Bernard Callède.111 The artist may have worried that blue on top of a yellow ground might render a green tone. Without extant easel paintings by this master, it is impossible to know whether he employed this method more broadly.112

Gray grounds are mentioned frequently in late sixteenth-century sources such as Ms. Français 640. Around 1580, the Flemish artist Hieronymus I Francken used a gray layer in his self-portrait (fig. 33), barely covered with brown glazes and white lead highlights to suggest a doublet and ruffled-collar shirt, producing a sketchy, intimate look.113 But again, without a cross-section, it is uncertain whether this gray layer is the ground layer.

Double-Colored Grounds

The earliest known example of a double-colored ground appears in wall paintings from Amiens Cathedral in 1506, with yellow ocher applied over white chalk and red lead.114 No contemporaneous source mentions this layering, but a seventeenth-century recipe collection, probably made by a surgeon from Orleans around 1649, advises the same pigments in reverse order, using lead white instead of chalk: ‟To paint on walls, first you should soak the wall with oil two or three times and add yellow ocher and a little red lead to allow it to dry. The best primer is made of white lead and a little red lead or another suitable color.”115

At Écouen (ca. 1550), at least some of the twelve painted mantelpieces have a dark gray over yellow double-color ground (see figs. 18, 19, and 20).116 The compositions give the impression that the work was divided among several painters in order to complete the decoration faster. Just like in Anne de Montmorency’s Book of Hours of the same period (Chantilly, Musée Condé), the elaborate, rare biblical iconography corresponds to a variety of styles in the execution. For the mantelpieces, Sylvie Béguin suggested the names of artists involved in the royal entry of 1549 in Paris—Charles Dorigny and Jean Cousin (along with sculptor Jean Goujon)—and interpreted these paintings as a French response to the new Fontainebleau frescoes, which seems consistent with the painting technique observed.117 They were also compared to rare, archival evidence about the château itself.118 More recently, the Hunt of Esaü in Constable Anne of Montmorency’s bedroom has been attributed to the Master of the Diana Tapestry, probably Charles Carmoy.119 The profile of this painter from Orléans in the Loire Valley interestingly matches the painting technique described, but there are at least three other hands to be identified.

By the late sixteenth century, such layering was more common. A recent case study is the Last Judgment by Jacques Le Pileur (see fig. 25). Born in Rouen to a painters’ family, Le Pileur may have continued his training as a journeyman in the Low Countries, as his composition recalls Raphael Coxie’s Last Judgment (1588–1589; Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent). After settling in Paris, Le Pileur received this commission in 1604 but had to quit due to health issues. The second painter who completed the work in 1605 remains unknown.120 Scientific imagery was critical in distinguishing the two phases. Conservation analysis revealed a first layer of red lead and chalk, overlaid with white lead and some particles of carbon black.121 Here, the traditional red lead ground of northwestern France was topped with a fashionable gray color, enabling subtle half-tones in the flesh. This is the method that Bloemaert, Ketel, and Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem may have seen in France in the 1580s and imported to the Netherlands. By the time Pierre Lebrun wrote his manuscript treatise (1635), such grounds had become the norm. Although the author describes red-brown and gray in separate passages, he may have intended them to be used in combination.122

A few years later (1644), Saint-Aignan provided a three-layer recipe to prepare canvas paintings:

Once the canvas is prepared with glue, left to dry, then pounced, you can add 2 or 3 preparatory layers. The first one can be made with the old oil from the brush pot mixed with Spanish white, red lead and yellow ocher; the second one using good colors like yellow ocher, red-brown, umber, red lead and some parts of white lead; the third one: white lead, sheep feet bone black, charcoal black and a bit of umber and red lead in order to make a gray that is close to flesh tone. You should not use either Flanders black, id est soot black, or Spanish white, because they would make your colors die.123

This treatise is the earliest known French source to indicate why a colored ground might be advantageous.

In sum, colored grounds in French paintings before 1610 fall into four main families: red-brown, orange, yellow, and gray. All of these colors have been identified before 1500. They were therefore not introduced by Italian artists working at Fontainebleau, and the prevailing assumptions about their origins require revision.

Conclusion

This research shows that colored grounds were already known to painters of Romanesque wall paintings and were used in easel painting from at least the fourteenth century. Some recipes mention specific supports, but scientific analysis reveals that nearly every type of ground composition was tried on a wide variety of supports. Painters chose their ground color depending on their pictorial intent, rather than on the properties of the material they wished to cover. Binding media also varied: most often oil, valued for its transparency and suitability for layering, but also lime in frescoes, and gum lac for a more opaque effect. As seen in paintings attributed to Jacob de Litemont, the dell’Abate family, and Ambrosius Bosschaert, an artist might change ground colors depending on his project. Indeed, the absence of specialization in France during this time made it a crucible for technical innovation.

Comparable creativity is evident in other domains—for example, the colors of size layers for gold leaf in Gothic illuminated manuscripts—suggesting fruitful areas for further comparison. Colored grounds are a striking example of how, in the medieval and early modern periods, style often evolved more quickly than painting techniques. Layering methods used to achieve chiaroscuro effects persisted for centuries, meaning that seventeenth-century recipes can still help interpret cross- sections from thirteenth-century paintings.

Collaboration between foreign and local artists is a common thread throughout the present study. France welcomed numerous foreign painters in the Middle Ages and the early modern period—some during their training as journeymen and others who settled for a longer time. Netherlandish court artists, such as Jan Boudolf, Johan Maelwael (or Henri Bellechose), Barthélemy d’Eyck, Jacob de Litemont, Coppin Delf, and possibly Henri de Vulcop all engaged with colored grounds while in France, but there is no evidence that they ever went back home and shared that workshop practice, unlike Bloemaert and other Netherlandish painters active in the 1580s. The networks linking Netherlandish artists who traveled to France deserve further investigation to better understand their contribution to the use of colored grounds in paintings.

This article brings together, for the first time, evidence of the rise and spread of colored grounds in France, beginning with their use in wall painting and tracing their adoption in easel painting. Once the phenomenon has been mapped at a large scale, it will be necessary to focus more closely on individual artists and stylistic groups in order to interpret the evidence with greater precision. Considering preparatory layers alongside other stylistic and technical clues will not resolve authorship or date questions on its own, but it can illuminate the cultural contexts in which artists worked.

Table 1 – Cases of Colored Grounds in French Paintings before ca. 1610

| No. | Date | Artist | Title | Place (French Département) | Technique | Ground | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12th century | Unknown artist | Scenes from the Old Testament, the Life of Christ and some saints (Peter, Martin) | Église Saint Jacques, Saint-Jacques-des-Guérets (Loir-et-Cher) | fresco | red-brown (red ocher) ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 2 | 12th century | Unknown artist | Christ in glory and the Tetramorph; Saints | Église Saint-Genest, Lavardin (Loir-et-Cher) | fresco | red-brown (red ocher) ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 3 | 12th century | Unknown artist | Scenes from the Life of Christ | Église Saint Martin, Nohant-Vic, (Indre) | fresco | red-brown (red ocher) ground, some yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 4 | 12th century | Unknown artist | Last Judgment | Église Saint-Julien, Brioude (Haute-Loire) | ? on wall | dark grey ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 5 | ca. 1246-1250 | Unknown artist | False-stones, geometrical motifs and coats of arms | Abbaye du Ronceray, Angers (Maine-et-Loire) | oil on wall | red-brown (red ocher) ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH)+ LIBS (Strasbourg, Epitopos) |

| 6 | ca. 1270-1280 | Unknown artist | Scenes from the Story of Saint Maurille | Cathédrale Saint-Maurice, Angers (Maine-et-Loire) | oil on wall | light orange (chalk, sand, red lead) | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 7 | ca. 1270-1280? | Unknown artist | Scenes from the Life of saint Georges | Cathédrale Notre-Dame, Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dôme) | distemper on wall | light orange (chalk, red lead) | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 8 | ca. 1275-1302 | Unknown artist | Six clerks from the de Jeu Family and an angel | Cathédrale Notre-Dame, Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dôme) | distemper on wall | red-brown (red ocher) ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 9 | ca. 1367-1385 | Ascribed to Jan Boudolf from Bruges | Angels playing some music | Cathédrale Saint-Julien, Le Mans (Sarthe) | oil on wall (casein-binded mortar) | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 10 | ca. 1389-1390 | Jean de Beaumetz and workshop | M and P on a green background (initials of Margaret of Flanders and Philip the Bold) | Château de Germolles, Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire) | oil on wall | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections + LIBS (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 11 | ca. 1390 | Unknown artist | Altarpiece wings showing saints (St Bernard/St Denis and the Virgin Mary; St Eloi/St John, and St Christopher | Musée des beaux-arts, Angers, (Maine-et-Loire), inv. MBA 1143 | oil (?) on oak | red-brown ground | no analysis, seen under microscope by Élisabeth Martin from C2RMF, Paris |

| 12 | ca. 1410 | Anonymous, maybe Colart de Laon | Angel Gabriel from the Annunciation, St Mary Magdalen introducing donor Pierre de Wissant; back: Apostles and Prophets (right wing from an altarpiece) | Musée d’art et archéologie, Laon (Aisne), inv. 990.17.31. | oil on oak | double yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 13 | ca. 1415 | Johann Maelwael or Henri Bellechose? | Virgin and Child with butterflies | Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, inv. 87.1 | oil on canvas | yellow ocher ground | XRF+ seen under microscope (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie |

| 14 | ca. 1442-1450 | Unknown artist | Tomb decoration for Louis II d’Anjou and Yolande d’Aragon | Cathédrale Saint-Maurice, Angers | murals with oil and gum binders | orange ground with red ocher | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 15 | ca. 1443-1444 | Barthélemy d’Eyck | Annunciation | Église de la Madeleine, Aix-en-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône) | oil on poplar | grey ground | cross-sections (The Hague, RKD) |

| 16 | ca. 1450 | ascribed to Jacob de Litemont | Angels on the vault of the chapel | Hôtel Jacques Cœur, Bourges (Cher) | oil on wall | some with a yellow ocher ground, others (under blue tones) with a grey ground made of lime and carbon black | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 17 | ca. 1460 | Master of Vivoin | 2 wings from an altarpiece from St Hippolyte priory in Vivoin near Le Mans: Martyrdom of St Hippolytus, Adoration of the Magi, Descent from the Cross; Virgin and child with St Benedict | Musée de Tessé, Le Mans, (Sarthe), inv. 10 | oil on oak, both sides divided into 2 panels, one panel transferred on canvas (Martyrdom) | orange yellow ocher + red lead ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 18 | ca. 1460 | Unknown artist | The Baptism of Christ | Église Saint Mélaine (once an abbey), Rennes (Ille-et-Vilaine) | oil on wall | yellow ocher ground | LIBS (Strasbourg, Epitopos) |

| 19 | after 1472 | Unknown artist | Crucifixion | Église Notre-Dame, Dijon (Côte d’or) | oil on wall | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 20 | ca. 1475 | Unknown artist (Pedro Berruguete?) | The Seven Liberal arts | Cathédrale Notre Dame, Le Puy-en-Velay (Haute-Loire) | mixed media (?) on wall | black / dark grey ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 21 | ca. 1475 | Anonymous (Netherlandish artist?) | Crucifixion; Noli me tangere and donors from the Breuil family | Cathédrale Saint-Étienne, Bourges (Cher) | oil on wall (with casein-binded mortar) | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 22 | ca. 1480-1485 | ascribed to Coppin Delf and assistants | Crucifixion, saints and angels playing instruments | Chapel in Montreuil-Bellay castle (Maine-et-Loire) | pigments and gum lac on wall and vaults | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 23 | ca. 1480-1490 | Unknown artist, maybe Pierre Garnier | Crucifixion, Pietà, St Bernard and a Cistercian donor | Cathédrale Saint-Maurice, Angers, treasure room | mixed technique (oil and proteins) on oak | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections+ amido black (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 24 | 1500 | Unknown artist | Tree of Jesse | Église Saint-Prix et Saint-Cot, Saint-Bris-le-Vineux (Yonne) | oil on wall | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 25 | ca. 1500 | François Lheureux | Scenes from the Story of St Meriadec | Église Saint-Meriadec in Stival, Pontivy (Morbihan) | oil on wall | yellow ocher ground | LIBS (Strasbourg, Epitopos) |

| 26 | ca. 1500 | Unknown artist | Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome mourning the dead Christ | Hôtel de Cluny, Paris (now the Musée national du Moyen Âge) | oil on wall | light pink yellow ocher-based ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 27 | ca. 1500-1510 | Unknown artist, maybe Jacques Thomas | Scenes from the Passion of Christ and Family of St Anne | Chapelle Sainte- Anne, Saint-Fargeau (Yonne) | animal glue distemper on wall (with casein-binded mortar) | yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 28 | 1506 | ascribed to the Master of Antoine Clabault (Riquier Hauroye ?) | 8 Sibyls | Cathédrale Notre-Dame, Amiens, chapelle St Eloi (Somme) | oil on wall | white, sometimes with a little red lead + second, yellow ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 29 | ca. 1530-1540 | Rosso Fiorentino | Pietà | Musée du Louvre, Paris, INV 594. | oil on wood transferred on canvas | dark grey ground on the second composition | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 30 | 1534-1539 | Unknown artist | Prophets and saints | Église Sainte- Barbe, Chambolle-Musigny (Côte d’or) | oil on wall | yellow ocher ground | no analysis, but condition report |

| 31 | ca. 1547-1550 | Noël Jallier and workshop, maybe after an Italian artist? | Scenes from the Trojan War | Château d’Oiron (Deux-Sèvres) | oil on wall (with casein-binded mortar) | red ocher ground | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 32 | 1549 | ascribed to Geoffroy Dumonstier | Exquisite Triumph to the faithful knight (‘Puy d’Amiens’, poetical allegory dedicated to the Virgin Mary) | Musée de Picardie, Amiens, inv. M.P. 5436 | oil on oak | orange (red lead) ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 33 | ca. 1550 | Unknown artists, among which maybe Charles Carmoy | 12 chimney mantlepieces with mainly scenes from the Old Testament | Musée national de la Renaissance, château d’Écouen (Val d’Oise) | oil on wall | yellow ocher, with sometimes a bit of orange red lead grounds (some with a second, grey layer) | cross-sections (Champs-sur-Marne, LRMH) |

| 34 | ca. 1560 | Unknown artist | Lady at her toilette | Musée des beaux-arts, Dijon (Côte d’or), inv. CA 118. | oil on canvas | orange ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 35 | ca. 1560-70? | Circle of Nicolo dell’Abate, maybe his son Giulio Camillo dell’Abate | The Threshing of wheat | Château de Fontainebleau (Seine-et-Marne), inv. F2474C, now on loan at Écouen château | oil on canvas | red-brown ground | no analysis, but condition report at C2RMF |

| 36 | 1569 | Ruggiero de’ Ruggieri | Ulysses protected from Circe’s magic | Château de Fontainebleau (Seine-et-Marne), inv. F1995-9. | oil on twill canvas | light orange ground with some red lead | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 37 | ca. 1571-1610? | Unknown artist after François Clouet | Lady at her bath | Les Arts décoratifs, Paris, inv. 15821 | oil on canvas | double grey ground | Aubervilliers, INP lab |

| 38 | ca. 1580-1590 | Unknown artist (probably made in Paris) | The Lady between two ages | Musée des beaux-arts, Rennes, inv. 803.1.1 | oil on canvas | red-brown ground | no analysis, but condition report at C2RMF |

| 39 | ca. 1580-1600 | Second school of Fontainebleau, once ascribed to Toussaint Dubreuil | Vertumnus and Pomona | Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 2007 8 | oil on canvas | double red-brown + grey ground | no analysis, seen under microscope at C2RMF, Paris |

| 40 | ca. 1581 | Unknown artist | Bal on occasion of the duke of Joyeuse’s wedding | Château de Versailles (Yvelines), inv. MV 5636/RF 1574/V 358. | oil on canvas | grey ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 41 | ca. 1590-1600 | Unknown artist | The Vision of Constantine | Château d’Azay-le-Rideau (Indre-et-Loire) | oil on twill canvas | red-brown ground | no analysis, but condition report at C2RMF |

| 42 | ca. 1591-1599 | Ambroise Dubois (ascribed to Ambrosius Bosschaert, called) | Gabrielle d’Estrées as goddess Diana | Château de Fontainebleau (Seine-et-Marne), inv. 2002.2 | oil on canvas | red-brown ground (red ocher, chalk and red lead) | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 43 | 1593 | Joris Boba (ascribed to) | Portrait of a man aged 39 | Musée des beaux-arts, Reims (Marne), inv. 851.4 | oil on canvas | yellow ocher ground | no analysis, but condition report at C2RMF |

| 44 | ca. 1600-1610 | Unknown artist, second school of Fontainebleau? Flemish painter in France? | Venus mourning Adonis | Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. DL 1970 20 | oil on oak | double light pink ground with ocher and white lead+ grey ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 45 | ca. 1600-1605 | Ambroise Dubois (ascribed to Ambrosius Bosschaert, called) | Chariclea nursing the wounded Theagenes | Château de Fontainebleau (Seine-et-Marne), inv. INV 4153/B 85 | oil on canvas | double red-brown + grey ground | cross-sections (Paris, C2RMF) |

| 46 | 1604-1605 | Jacques Le Pileur (finished by an unknown painter) | Last Judgment | Église Saint-Étienne du Mont, Paris | oil on twill canvas | double orange (red lead) + grey ground | cross-sections (Pessac, CESAAR) |