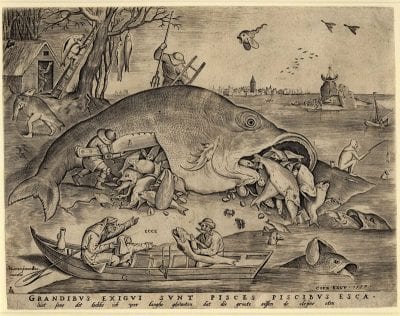

In 1557 the Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Cock published the print Big Fish Eat Little Fish. Although the print was designed by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, it was credited to the invention of Hieronymus Bosch. This essay argues that the style and subject matter of Cock’s “Bosch” prints changed around the time Big Fish Eat Little Fish was published. The “Bosch” prints shifted from featuring large-scale hellscapes readily associated with Bosch to smaller-scaled scenes of folly more often associated with Bruegel. It seems that the success Bruegel enjoyed in creating Boschian imagery under his own name effectively altered the imagery Cock published as by “Bosch”.

In 1557, the Antwerp publisher Hieronymus Cock produced the print Big Fish Eat Little Fish (fig. 1). Although the engraving was based on a drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569), Cock credited the design to Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450–1516), whose imagery was imitated by followers well into the sixteenth century.1 The rationale for replacing Bruegel’s name with that of Bosch at this particular moment remains a question. Between 1555 and 1557, Cock published thirteen engravings after Bruegel’s landscapes and the designs Patientia and the Ass at School, all of which bear Bruegel’s name as inventor. Hans Mielke has observed that since Bruegel was already an established artist in his own right, Big Fish Eat Little Fish was not necessarily an attempt to capitalize on the marketability of Bosch’s name. Perhaps, as proposed by Matthijs Ilsink, working in a Boschian mode was a means for Bruegel to emulate an artist he admired.2 Whatever the reason may be, Bruegel was able to successfully evoke Bosch and would continue to do so in numerous prints he designed for Cock under his own name. This contributed to the chronicler Ludovico Guicciardini’s declaration of Bruegel as the second Bosch.3

That moniker is of interest, particularly as Bruegel was not the only artist to have anonymously designed prints that Cock published under the name Bosch, nor was Bruegel the only artist to have incorporated Boschian motifs into works published under his own name. Yet it is Bruegel who was claimed as Bosch’s sole heir by Guicciardini. The reason for this proclamation may in part be found in Cock’s publication of “Bosch” prints. This essay will analyze the Bosch designs Cock produced, demonstrating that the compositions not only included motifs associated with Bosch but also that a number of the prints instead incorporated subjects more readily associated with Bruegel, namely comic depictions of peasants and fools. This change in subject matter and style of Cock’s “Bosch” prints arguably occurred around the time when Bruegel’s Big Fish Eat Little Fish was published. Shortly after its release, Cock’s “Bosch” prints shifted from featuring Boschian hellscapes to Bruegelian scenes of folly, effectively altering the tone and style of Boschian imagery.

Hieronymus Cock and the Early Production of Boschian Prints

Cock established his publishing house, Aux Quatre Vents (At the Sign of the Four Winds) around 1548.4 To develop a client base, Cock initially supplied a Flemish art market enthusiastic for Italian Renaissance images. In 1550 he engaged the services of the Italian engraver Giorgio Ghisi, who produced engravings after Raphael and Michelangelo, and eventually works after Flemish Romanists such as Lambert Lombard (1506–1566) and Frans Floris (ca. 1519–1570).5 By 1555 Cock began to shift away from publishing prints after Italian and Italianate paintings and instead began to offer engravings after distinctly northern subjects.6 This shift aligns with the start of Pieter Bruegel’s collaboration with Cock in 1555. Cock published sixty-four prints after Bruegel’s drawings, of which approximately one third feature subject matter that relates to that of Bosch. Cock also published forty-six prints designed by others but attributed to Bosch. Few of those prints, the earliest of which is the Ship of Fools of 1559 (fig. 3), are dated, Another print, Christ Led to the Crucifixion (fig. 4), can be shown to have been published even earlier. The drawing for this undated Bosch-attributed print is signed by Lambert Lombard and dated 1556, the same year Bruegel designed Big Fish Eat Little Fish.7 It therefore seems reasonable to assume that, as with the Bruegel prints, Cock’s initial publication of Boschian prints coincided with a developing interest in producing engravings after northern artists. The challenge in creating “Bosch” prints was that the designs needed to evoke the widely understood perception of Boschian compositions.

Almost immediately after Bosch’s death in 1516, painters began to appropriate his distinctive imagery.8 This was not only due to the widespread fascination with Boschian imagery but also because his memorable monsters and devils were easily imitated and therefore could be capitalized upon in painted and printed form.9 As the early chroniclers highlighted, it was those very monsters that were synonymous with the name Bosch. Felipe de Guevara in his Comentarios de la Pintura (ca. 1560–63) lamented the fact that imitators of Bosch, who often signed Bosch’s name to their paintings, merely painted monsters and devils, creating the impression that Bosch only painted diablerie.10 A survey of the most frequently copied images by Bosch followers substantiates Guevara’s claim. The Temptation of Saint Anthony and The Last Judgment, two compositional types that teem with devilish creatures, were the most commonly produced Boschian paintings, while only a handful of images replicate Bosch’s paintings of folly, such as the Stone Operation.11

This perception of Bosch in the sixteenth century directly relates to Cock’s production of Bosch prints and Bruegel’s Boschian prints. The 1557 Big Fish Eat Little Fish was not, in fact, Bruegel’s first Boschian design for Cock. In keeping with the representative “Bosch” compositions, Cock published the Temptation of Saint Anthony in 1556, which bears only Cock’s address. Although the print and the related drawing are not signed, the design is accepted as by Bruegel.12 The print was likely Bruegel’s first collaboration with the engraver Pieter van der Heyden, who would engrave most of Bruegel’s Bosch-inspired drawings as well as several designs attributed to “Bosch.”13 That neither Bruegel nor Bosch received credit for the design is intriguing. Perhaps the success of Saint Anthony prompted Cock to commission a second print from Bruegel, Big Fish Eat Little Fish, and add Bosch’s name. Since Bosch at that time had greater name recognition than Bruegel and was associated with the sort fantastic creatures included in the design, the print might have sold better if claimed for Bosch.

While the two prints certainly demonstrate that Bruegel effectively appropriated Boschian motifs, particularly the diabolic creatures and strange architectural forms, he seems to have done so in a different spirit. Bosch’s paintings tended to have a pessimistic view of the world, in which humanity is condemned to the tortures of hell.14 Bruegel, however, used these motifs to comment on human folly, and he did so within a less nightmarish context. The creatures in Bruegel’s Boschian prints appear more rounded and corpulent; they are playful rather than dangerous, making the images amusing rather than threatening.15 Karel van Mander, in his 1604 Schilderboeck, emphasized, more so than previous chroniclers, the humorous quality of Bruegel’s work, coining Bruegel’s nickname, “Pier den Drol.” Van Mander and other sixteenth-century chroniclers do not use the word “droll” to describe the works of Bosch. Thus, it appears that the imagery created by the two artists evoked different responses in their time.16

From Horror to Hilarity: Transforming the “Boschian” Image in Print

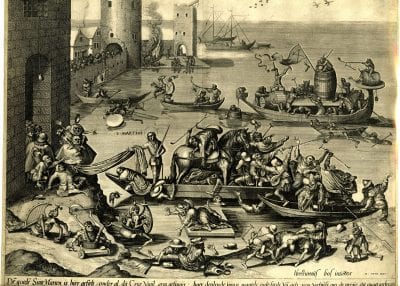

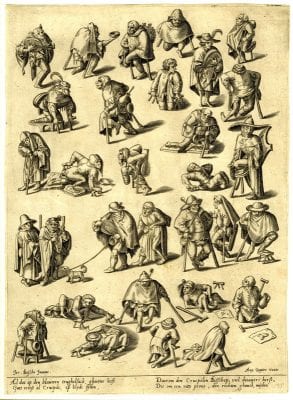

Such distinct perceptions of Bosch’s imagery as frightening and that of Bruegel as humorous would become conflated during the course of Cock’s production of Bosch-attributed prints. A visual analysis of all the “Bosch” prints that Cock issued allows them to be placed roughly into two groups which demonstrate a clear shift in Cock’s production of Boschian imagery from nightmarish to droll. The first group includes undated prints: the Last Judgment (fig. 2), the Besieged Elephant, Christ Led to the Crucifixion (fig. 4), and Saint Martin in a Boat with Cripples and Beggars (fig. 5). All are composed of large-scale, densely populated scenes filled with a multitude of diabolic monsters. The second group includes dated prints: the Ship of Fools (1559, fig. 3), the Blind Leading the Blind (1561), Musicians in a Mussel Shell (1562), and Shrove Tuesday (1567, fig. 6). The prints in this category are smaller-scale scenes of folly which feature several monumental figures that fill the image. While the prints in both categories can be linked to models connected to Bosch, those listed in the second group no longer portray nightmarish hellscapes filled with a myriad of tiny creatures and figures — compositions typically associated with Bosch. Moreover, the prints in the first group depict mostly religious subjects that allow for a more severe didactic tone, while those included in the second group are genre scenes that tend to be light hearted by nature of the subjects portrayed. A comparison of a print from each grouping illustrates these differences.

The Last Judgment revives the triptych format of Bosch’s paintings in Vienna and Bruges. Beyond that the composition is a jumble of Boschian motifs that do not derive from a single painted source.17 Possible models may include paintings by Bosch followers Jan Mandijn (ca. 1500–ca. 1559) and Pieter Huys (ca. 1520–ca. 1584), but a more likely source is an engraving of the Last Judgment by Allart du Hameel, a skilled engraver and intermediary for Boschian imagery, who resided in Bosch’s home city of ‘s Hertogenbosch from 1478 to 1495.18 Du Hameel’s engraving includes the name “Bosch” at the top left center of the print. This was most likely not an attempt to fool viewers into believing the engraving was by Bosch but rather a mark of the place of its conception, s’Hertogenbosch. Cock or his designer perhaps assumed “Bosch” meant the prints were after the painter, not a reference to location.19 Although the center panel of the “Bosch” Last Judgment no longer contains Christ seated on an arc, other compositional elements recall Du Hameel’s engraving such as (in reverse) the dilapidated tower to the left and the barren cliff climbed by the saved to the right. Both prints feature unwelcoming rocky landscapes densely populated with attenuated figures tortured by demons that lend to the overall threatening atmospheres that strongly recall the hellscapes for which Bosch was best known.20 The Ship of Fools (fig. 3), from the second group, contrasts with the Last Judgment in tone. It loosely recalls Bosch’s painting of the Ship of Fools from 1500.21 Both the painting and print feature a group of merrymakers in a boat piloted by a fool however, the figures appearing in the print are a parody of those in the painting. They are coarser, more corpulent, and have exaggerated features and expressions, which taken together add a comic note to the composition that is less prominent in Bosch’s moralizing painting.22 Indeed, the print version of the Ship of Fools no longer includes the monk and nun featured in Bosch’s painting, which alters possible interpretations of the image.23

Cock’s Last Judgment retains the more severe spirit of Bosch’s paintings, whereas the Ship of Fools stylistically and thematically moves away from a Boschian source.24 Instead, Cock’s Bosch-attributed prints of fools and peasants bring to mind the humorous designs Bruegel created for Cock. It seems logical to propose that Cock’s publications of “Bosch” prints did not fluctuate between devil-riddled landscapes and scenes populated with comical figures but rather were the result of an evolution in what was accepted as Boschian imagery. This suggestion directly links to the time when Cock published Bruegel’s Big Fish Eat Little Fish, which arguably was a tipping point in what could be considered a design by “Bosch”.

Of the undated large-scale prints from the first group, only Christ Led to the Crucifixion can be reliably dated to ca. 1556, based on signatures on the drawing for the print.25 The similarity in scale and compositional style of the Last Judgment, the Besieged Elephant, and Saint Martin in a Boat with Cripples and Beggars may indicate that they were also produced in the years surrounding 1556 as well.26 In 1557 Cock published Big Fish Eat Little Fish, which was distinct in terms of size and style from the large-scale prints that had been released up to that point as by “Bosch.” At the same time, Bruegel continued to design prints under his own name which included Boschian imagery, such as the Seven Deadly Sins (1558), and scenes of folly, such as Everyman (1558) and The Alchemist (1558?). Meanwhile, with the exception of the Temptation of Saint Christopher [Anthony?] (1561), Cock all but ceased to publish prints credited to Bosch that portrayed hellish scenes populated with devilish creatures.27 Instead, the prints that Cock published bearing Bosch’s name almost entirely focus on scenes of folly more readily associated with designs by Bruegel.28 It seems that Cock saw fit to bring out prints that looked more like the material Bruegel designed and published those designs under the name Bosch.

The Bosch-Bruegel Synthesis

The degree to which imagery attributed to Bosch became entangled with Bruegelian imagery is demonstrated by the Bosch-attributed print Shrove Tuesday (1567; fig. 6). The composition recalls Bruegel’s The Alchemist (1558) and the anonymous prints published by Aux Quatre Vents after 1570, Carefree Living and Dirty Sauce. Shrove Tuesday includes few references to Bosch and instead employs the setting of a dissolute household.29 In order to remind the viewer that Shrove Tuesday is in fact after “Bosch,” the designer cleverly inserted a print within a print. Pinned to the chimney flue is a print featuring a Boschian creature dressed as a pilgrim. The print is signed “Bosch” and thus serves the double function of referencing Bosch prints and crediting Bosch as the designer of Shrove Tuesday. That, along with the monster standing prominently in the foreground, is the only reference to typically Boschian imagery. It is Bruegel’s humorous scenes, instead, that come to mind. A drawing after Shrove Tuesday signed “Bruegel” underscores this point.30 The drawing is identical to the “Bosch” print of the subject except that the drawing omits the strategically placed “Bosch inventor” beneath the owl-pilgrim print. The fact that the drawing is oriented in the same direction as the print and is crudely executed suggests that the sketch was not a design by Bruegel for the engraving but rather a later copy after the print. Regardless, the signature shows that later audiences, despite Cock’s attribution of the print to “Bosch,” identified such humorous images as inventions of Bruegel.

Another drawing signed “Bruegel” further supports this theory. The Brussels drawing Cripples and Beggars, signed “Bruegel 1558,” resembles the unsigned sheet Cripples and Beggars in Vienna.31 The Vienna drawing has been attributed to Bosch based on its relationship to a print published by Cock’s widow, Volcxken Diericx, which names Bosch as its inventor (fig. 7). Although the Brussels drawing is no longer accepted as by Bruegel and the Vienna drawing as by Bosch, the respective signatures on the drawings and print indicate that the conception of Bosch and Bruegel imagery had become so blurred that designs attributed to Bosch’s invention could just as easily be considered as being by Bruegel, as made clear by the apocryphal signature on the Brussels drawing.32 Humorous images credited to Bosch or Bruegel seemingly became interchangeable.

Perhaps the best example of this conflation is one that brings us back to where we started, Big Fish Eat Little Fish. In 1619 Hendrick Hondius engraved a reverse copy of Big Fish Eat Little Fish, and, as in the original, he included Bosch’s name as the designer. However, when a third state of the print was issued by the publisher Claes Jansz. Visscher, Bosch’s name had been replaced with that of Bruegel.33 As Visscher is not known to have been in possession of the signed drawing, it might be assumed that he, in keeping with a common perception of Bosch prints at the time, had come to consider designs by Bosch interchangeable with those by Bruegel. Following that line of thought, it also might be assumed that Visscher judged Bruegel’s name as more saleable than that of Bosch. Bruegel no longer seems to be a second Bosch, but rather Bruegel’s popularity had eclipsed that of Bosch, turning Bosch into a second Bruegel.