Rembrandt’s representation of his own features in Beggar seated on a Bank (etching, 1630) gains resonance in the context of a visual and literary tradition depicting “art impoverished” and reflects the artist’s struggle for recognition from patrons such as Stadholder Frederick Hendrik at a pivotal moment in his early career.

Two figural motifs recur frequently in Rembrandt’s etchings of the 1630s: ragged peasants and the artist’s own startlingly expressive face. On a copperplate that he treated like a page from a sketchbook, these disparate subjects are juxtaposed.1 And in an etching of 1630, they merge, as Rembrandt himself takes on the role of a hunched figure seated on a rocky hillock (fig. 1). Early cataloguers such as Edmé-François Gersaint (1751) and Adam Bartsch (1797) failed to notice the resemblance and classified the print with other studies of beggars rather than with self-portraits.2 Ignace-Joseph de Claussin (1824) was apparently the first to observe that “the physiognomy has a great deal of resemblance to Rembrandt.”3 This discovery was overlooked by later cataloguers more concerned with distinguishing states of the print and separating it from deceptive copies.4 It was taken up again by Arthur Hind (1912), who drew a convincing connection to Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait Open-Mouthed as if Shouting, also dated 1630 (fig. 2).5 Nevertheless, in most modern sources it has retained the title Beggar Seated on a Bank.6 Gersaint described the beggar’s frizzled hair and ruined garments, but Daniel Daulby (1796) was the first to remark on the emotional intensity of this figure “asking alms with a countenance full of distress.” Bartsch described him as groaning in misery.7

It has gone unremarked that of all the wretched characters in Rembrandt’s prints of the 1630s, Beggar Seated on a Bank is the only one who is a beggar in the literal sense, extending his palm in a direct appeal to the viewer. The fact that Rembrandt chose to combine this singular gesture with a self-portrait hardly seems accidental. Modern scholars accept that the beggar’s face is Rembrandt’s but differ in their speculations about why he cast himself in such a role. Some assume that his physiognomic studies simply provided a convenient model.8 Others infer an expression of Christian empathy with human misfortune and poverty. The conflicted attitudes of Rembrandt’s contemporaries toward indigence have been widely explored: while Protestant doctrine encouraged charity for the deserving poor, disreputable idlers were met with scorn. For the present study, this complex topic remains in the background.9 Instead, I take a cue from Clifford Ackley, who remarked in the exhibition catalogue Rembrandt’s Journey that “this extraordinary bit of role-playing . . . should perhaps be viewed . . . as a good, if inside, joke. The twenty-four-year-old artist was not yet fully established and could use some financial assistance!”10 Ackley’s observation is perceptive, but in my view, there is more at stake here than money. I propose to read this print as a wry response to Rembrandt’s struggle for recognition at a pivotal moment in his early career. My contextual analysis places it within a tradition of self-referential imagery that comments on the status of the artist at the mercy of market forces.

In 1630, Rembrandt was becoming well-established in his home city of Leiden, but he was also angling for more prestigious patronage from the Court of Stadhouder Frederik Hendrik in The Hague. This ambition was matched by his colleague Jan Lievens (1607–1674), whose proximity offered both a creative stimulus and a competitive challenge. The two worked closely together in Leiden; their drawing and painting styles were so similar that even contemporaries sometimes had trouble telling them apart.11 Lievens had recently convinced the Stadhouder’s secretary, Constantijn Huygens, to pose for a portrait, earning praise for both his initiative and the fidelity of the result.12 Such assertive self-confidence later helped Lievens to secure prestigious commissions in England, Flanders, and Brandenburg as well as the Dutch Republic.13

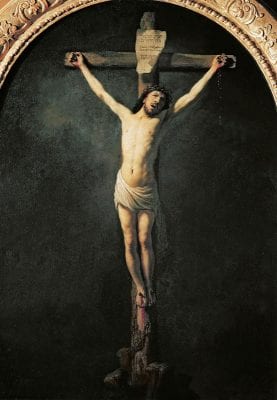

It was probably Huygens who placed both artists in the running for an important commission from Frederik Hendrik: a series of paintings depicting the Passion of Christ. As trial pieces, both submitted stark, emotional images of Christ on the Cross. Rembrandt turned again to his studies of his own face for the agonized expression of Jesus (fig. 2, fig. 3).14 He won the commission, but he did not manage, as Lievens did, to build a sustained record of aristocratic patronage. Rembrandt’s only court portrait depicts Frederik Hendrik’s aristocratic wife, Amalia von Solms, as a sober Dutch matron; it was quickly replaced with a more glamorous portrait by Gerrit van Honthorst (1590–1656).15 While Lievens eventually modulated his style toward classical finesse, Rembrandt resolutely maintained his independence from this growing trend. Yet, the difference in their success with patrons must have been due as much to personality as to style or talent. Later documents reveal that Rembrandt was reluctant to ingratiate himself with clients and even willfully disregarded their wishes. This is evident, for instance, in his dispute in 1654 with Diego D’Andrada over changes to the portrait likeness of a young girl, and in the rejection of several of his etchings commissioned as book illustrations.16 I suggest that this reluctance already manifests itself in Beggar Seated on a Bank. For a personality to whom diplomacy did not come naturally, the need to curry favor at court must have been both difficult and distasteful.

This context may shed light on a cheeky response to Rembrandt’s etching that has gained scant attention (fig. 4). This rare print, a “large, rough copy in reverse” (in Hind’s words), is unsigned but was attributed to Lievens by Dmitri Rovinski. The sketchy style and definition of form with long, sinuous strokes are consistent with Lievens’ early etchings.17 This is not a deceptive copy, but rather an interpretation or even a critique of Rembrandt’s small, ragged figure. The modeling of the costume is simplified, and the gesture of the begging hand is enhanced by deeper shading in the palm. Rembrandt’s curly hair and broad nose remain unmistakable, but the size of the head is exaggerated, and the expression gains a touch of madness with a wild glint in the right eye and a roguish squint in the left. Significantly, this plate is much larger than Rembrandt’s (320 x 200 mm vs. 115 x 69 mm), another factor that heightens its visual impact and its satirical potential. While Rembrandt’s beggar is not overtly humorous, Lievens makes it more so. This suggests that at least one close contemporary understood Rembrandt’s motive to be self-referential wit rather than Christian empathy.

The analysis of humor in Rembrandt’s work remains to be written; commentators have focused instead on his ability to render complex, often tragic states of emotion. Constantijn Huygens was one of the first to recognize this talent with his vivid description of the central figure in Rembrandt’s Judas Repentant (private collection, England), painted in 1629. (Perhaps not coincidentally, that figure is also a supplicant.) In the same text, Huygens comments that Rembrandt prefers to work on a small scale while Lievens “does not just accurately duplicate the size of figures, but makes them larger.”18 Thus, when Lievens enlarges Rembrandt’s beggar, he may also be asserting his own superiority–as if to show Rembrandt what this satirical figure could look like if treated with the ambition and audacity for which he, Lievens, was already becoming known.

At the same time, by retaining the likeness of his friend, Lievens joins in Rembrandt’s acerbic commentary on the artist’s need to beg not just for financial support but also for appreciation from connoisseurs. And in this competitive environment, sometimes a provocative statement was the best way to attract notice. For instance, according to Karel van Mander (1604), Hans von Aachen secured a position as court painter to the Hapsburg emperor Rudolf II by crafting a self-portrait that depicted the artist as a rogue. This maneuver became a hallmark of Von Aachen’s genre imagery (one version may later have inspired Rembrandt’s depiction of himself as the prodigal son), and other young artists across Europe developed unconventional self-portraits as a means of showcasing their ambition and creativity. Several of Rembrandt’s early paintings and prints, including Beggar Seated on a Bank, may be seen as contributing to this trend.19

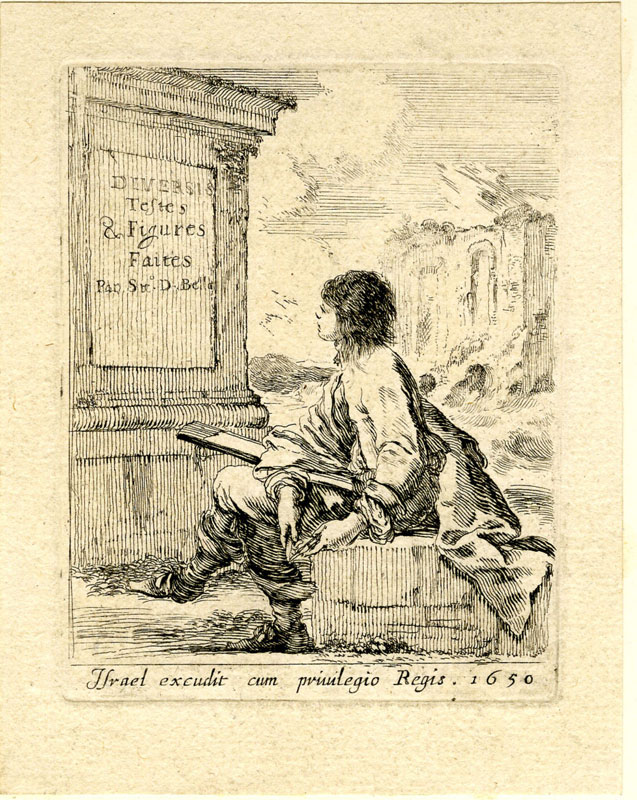

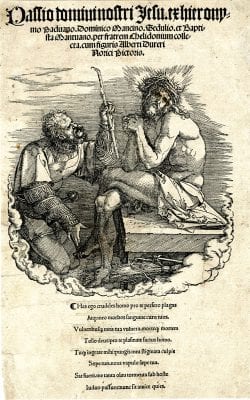

Rembrandt derived his images of beggars, including this one, not only from direct observation but also from close study of other printmakers. One mendicant figure from Jacques Callot’s series of twenty-five gueux (1622–23) is frequently cited as a precedent (fig. 5). Significantly, the title page to Callot’s series casts a roving troupe of vagabonds as baroni, or scoundrels: untrustworthy deceivers who live by their wits.20 This suggests an association between these colorful characters (and the printmaker’s clever rendering of them) and the perception of artists as tricksters who deceive their viewers through the lifelikeness of their imagery. Robert Baldwin and other scholars have associated Rembrandt’s apparent empathy for the poor with the Christian view that all of us are dependent upon the benevolence of God.21 Baldwin interprets Rembrandt’s beggars as a secular version of the Man of Sorrows, but he stops short of applying this connotation to the artist’s depiction of himself as a beggar. Yet, this suggests another visual tradition that might have prompted Rembrandt’s role play. As he pondered his own Passion series, he may well have consulted Albrecht Dürer’s treatments of the theme. In the frontispiece to the Large Passion, Christ as the Man of Sorrows sits hunched on a rough stone block (fig. 6). His features bear a striking resemblance to those of Dürer himself.22

While Christ as the Man of Sorrows bears the burden of sinful humankind, the sorrowing artist may have more practical concerns. In referencing such prototypes, Rembrandt did more than build on iconographic tradition: he approached his etchings of beggars, and of himself, as performances crafted in a medium designed for circulation and for comparison with the works of other artists (one of the perennial delights of print collecting). Self-identification in this case might suggest devotion or empathy, but, like the dozens of other self-portraits Rembrandt produced, it also constitutes an assertive foregrounding of artistic agency. This context facilitates the shift in perspective from begging for alms to begging for attention.

Together with representations of the studio and allegories of Art, early modern self-portraiture has been widely understood to comment metonymically on the status and practice of the artist’s profession. Within this imbricated tradition, a principal goal was to promote painting as a noble liberal art by depicting the artist as a person of genteel bearing and/or intellectual accomplishment.23 The young Rembrandt both contributed to this initiative, beginning with his etched Self-Portrait in Soft Cap and Embroidered Cloak (1631, fig. 7),24 and stood apart from it–nowhere more so, it would seem, than in Beggar Seated on a Bank. I suggest that the connotations of the etching are enriched if we imagine the figure in toto–not just Rembrandt’s face added to it–as a representation of the artist. In this context, the long, loose coat could be the tattered remnants of a painter’s smock.25 In happier circumstances, the seated, outdoor pose might reflect depictions of artists sketching en plein air (for example, fig. 8).26 The tragedy of Rembrandt’s poor artist is that he is alone and powerless, bereft of the tools of his trade. Perry Chapman notes that artistic melancholy was associated with creativity but also with idleness, poverty, and ostracism from society.27 The key point here, however, is that Rembrandt’s depiction of himself as indigent and unkempt directly contravenes the ideal of the gentleman-painter. Crafted in full awareness of this ideal–which the artist himself took up only a year later (fig. 7)–it becomes a parodic inversion of the suave social-climbing in which contemporaries such as Honthorst and Lievens actively engaged. As such, it contributes to an alternative literary and visual tradition: the depiction of Art impoverished.

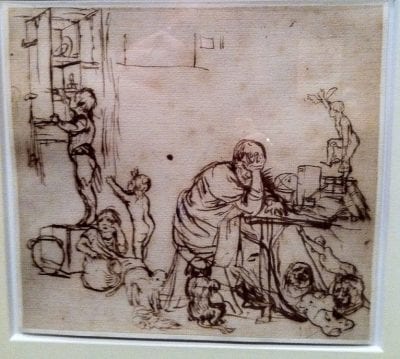

Constantijn Huygens, in a poem published in his anthology, Koren-Bloemen (1658), satirizes a painter he calls “Jan Klad,” who has been forced to sell all his possessions and drowns his sorrows in drink. In the literary tradition to which this poem belongs, the connoisseur blames the artist for his own troubles. Financial poverty results from indolence and lack of skill–the painter is “poor” in more ways than one.28 In contrast, allegories composed from an artist’s perspective express the challenges of earning a living from one’s art. In a drawing by Adam Elsheimer (1578–1610) (fig. 9), the destitute artist is distracted by the demands of a hungry family. A statuette on his drawing table depicts genius tied down by earthly care.29 A similar scenario is repeated in several prints after a composition by Andries Both (1611/12–1641).30 In Beggar Seated on a Bank, the young Rembrandt takes this lament out of the home and into the street. With the figure’s direct appeal to the viewer, he addresses the root cause of the painter’s travails: the necessity of soliciting attention from patrons and the marketplace.

The theme of Art impoverished was familiar in Italy as well. In his poem Lamento della pitture sul l’onde venete (Mantua, 1605), Federico Zuccaro (ca. 1541–1609) dressed the character of Painting in rags to signify a state of degradation brought on by the replacement of the refined style of Titian (ca. 1488–1576) and Veronese (1528–1588) with the sketchy (and more efficient) technique of Tintoretto (1519–1594).31 In Florence in the late 1640s, Salvator Rosa (1615–1673) drew an allegory of “Painting as a Beggar” (fig. 10).32 Like Rembrandt’s Beggar Seated on a Bank, Rosa’s Pittura is an isolated figure, seated outdoors on a rock and appealing for aid to the spectator. Her maulstick, palette, and brushes lie discarded on the ground. In her outstretched hand, she carries a begging bowl, but rather than confront the viewer, she bows her head despondently, while a winged cherub solicits sympathy with a banner that reads “Gentlemen, give alms to poor Painting.” Related themes feature in several other works by Rosa and in his poetic satire, La Pittura (ca. 1651).33 Interestingly, Rosa was an admirer of both Rembrandt and Lievens and a fractious personality who shared Rembrandt’s ambivalence toward dealing with patrons. Wendy Wassyng Roworth associates his satires on art with “Rosa’s frustrations during the period when he left behind the ‘golden chains’ of [the Medici] court for riskier, more rewarding opportunities in Rome.”34 It is easy to see a parallel with Rembrandt’s circumstances in 1630, as he debated between the struggle for court patronage from the House of Orange and the lure of Amsterdam.

As the open market for art developed in the Dutch Republic, Rembrandt and his contemporaries were less dependent on commissions than their predecessors had been, but they still had to find buyers for their work. Indeed, the decline of sinecures such as court appointments created a greater requirement that the artist operate as both craftsman and salesman, producing art as a commodity in search of a market. Among theorists, this condition occasioned a running debate over artistic motivations and their merits: as described by Rembrandt’s former pupil Samuel van Hoogstraten (1678), love, honor, and profit were the key factors driving artistic creativity.35 One Dutch author, Philips Angel, argued in 1642 that the marketability of works of art as tangible commodities was a factor that did not dishonor painting but, rather, rendered it superior to literature.36 In 1634, Rembrandt inscribed Burchard Grossmann’s album amicorum with the motto “A pious soul values honor above profit,”37 but this sentiment would have been impractical for many–including himself. The Passion series dragged on for over a decade, occasioning a set of documents that constitute the most significant literary artifact remaining to us from Rembrandt’s career: the seven letters he wrote to Constantijn Huygens concerning two paintings in the series. In two letters of 1639, he is truly compelled to assume the role of beggar, soliciting Huygens’s assistance in obtaining long overdue payment for his work.38

In this context, Beggar Seated on a Bank is revealed as a deceptively simple image with profound implications–a statement on the plight of the artist reliant upon the buyer’s goodwill. In offering this reading of Rembrandt’s print, I suggest that the principal issue at stake is not poverty, but dependency. Like all who make their living providing a commodity or service, an artist perpetually stands beholden to his clientele. For a fiercely independent creative spirit, the irritations of this condition are clear. Just as “people skills” are valued in business today, artists in Rembrandt’s milieu who gracefully negotiated their relationships with patrons and the marketplace found a smoother path to success than those (like Rembrandt) who did not. In Rembrandt’s self-portrait as a beggar, we glimpse a witty and artful response to these challenges.