This fifth and last installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits focuses on works by Govert Flinck (Oud Holland 7 1889]: 45–60). Meijer’s article was originally published in five installments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland. For translations (also by Tom van der Molen) of the first two installments on Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy (among others) and Rembrandt’s Nightwatch, respectively, see JHNA 5, no. 1 (Winter 2013); for the third, on Bartholomeus van der Helst, see JHNA 6, no. 1 (Winter 2014); and for the fourth, on Thomas de Keyser, see JHNA 6, no. 2 (Summer 2014).

The founding of the new building of the Arquebusier Civic Guard Hall has proved of such great consequence for Dutch painting, that it would have been truly a pity if we could not know the gentlemen who made possible the building of the hall for which Rembrandt and Van der Helst delivered their most splendid paintings.

We are therefore inclined to forgive the vanity of the four governors, who, after the building was finished in 1642, had their portraits painted for placement on the chimney on the west side of the hall [fig. 1].1 Those governors were: Burgomaster Albert Coenraedsz Burgh, Alderman Pieter Reael, and the council members Jan van Vlooswijck and Jacob Willekens. The latter was the commander who, while still retaining his rank in the Amsterdam Civic Guards, had conquered the Allerheiligen-Baai [Baia de Todos Santos, near Salvador] in Brazil for the West India Company.

The gentlemen did not choose Rembrandt but one of his former pupils who was in the process of emancipating himself from his teacher’s influence, being

Govert Flinck

As a matter of fact, Flinck was [earlier] a pupil of Lambert Jacobsz, the artist and Mennonite teacher. His coreligionist Vondel had bade farewell to him in 1620 in a wedding poem when Jacobsz left for Leeuwarden where he had found his [bride] Aecht.2 Ten or twelve years later when he visited the city of Cleves, Jacobsz was addressed there by an honorable citizen who had heard his edifying sermon and had learned so much of his [Jacobsz’s] modest way of life that he asked if he could entrust him with his son. The son had an unquenchable inclination for the art of painting.3 Lambert Jacobsz took the boy to Leeuwarden and taught him, together with his own son Abraham (later in Leiden called van de Tempel)4and Jacob Backer. A couple of years later he sent Backer and Flinck to Amsterdam5 to stay for some time in the workshop of Rembrandt, which was so frequently visited.6 Flinck took part there in the exercise Rembrandt set his pupils on the subject of the blessing of Jacob by Isaac [fig. 2], the depiction of which he would repeat a number of times later on.7 But he soon left that invaluable school and became independent.8 Already at the age of twenty-one (he had been born on January 25, 1615) he painted a shepherdess that is presently in the museum in Braunschweig9 and the portrait of Jacob Dircksz Leeuw, which has been discovered in the Rijpenhofje in 1876 by A. D. de Vries.10 After that, various distinctive portraits focused attention on his talent — the young soldier now in the Hermitage,11 the gray man now in Dresden (1639),12 the shepherdess from the Louvre (1641),13 and the portrait of a woman (1641), which has gone into the collections of the Berlin Museum from the Suermondt gallery.14 This resulted in the confident commission of the group portrait that shows the governors of the Arquebusiers Civic Guard. He fulfilled the task commendably, as we can still judge nowadays (although it seems to me that the painting has not been spared overpainting) in the third section of the Gallery of Honor to the right [in the Rijksmuseum], where it received a rather high place on the wall. The composition is the usual: four gentlemen in black, wearing hats, seated on chairs with red-leather backs on four sides of a table covered with a Smyrna rug. The man sitting on the side of the table towards the spectator is turning his head. Two others give the impression, from their hand gestures, of being in quite a lively conversation. The stage is enlivened a bit by the figure of an old man (a well-painted head), who — bareheaded — arrives to place the guild drinking horn on the table — the sixteenth-century buffalo horn with a silver foot in the shape of a tree trunk flanked by a lion and a dragon [fig. 3].15 In the top right corner, the dark background of the painting is broken by a shield in a heavily ornamented gilt frame. On the shield, a golden bird’s claw is visible, the old symbol of the Arquebusiers.16

The work seems to have been executed to the satisfaction of the civic guards; at least, a couple of years later (1645) Flinck was honored with the commission of another civic guard painting [fig. 4] for adorning the same room [in the Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall], later in the burgomasters room in the town hall on Dam square, from which it was brought to the Rarities, or Weapon, room of the present town hall.17 Nowadays it has a deserving place in the Rembrandt Room of the [Rijks]museum, where it acts as a pendant to the Sandrarts18 on the other side of the doorway, just as those paintings used to hang, on both sides of the fireplace in the Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall. It is without a doubt Flinck’s masterpiece and one of the finest products of the Dutch school of painting, warm of tone and rich in color, full of beautiful figures, well modeled and ordered with great judgment. Rembrandt’s influence is not traceable in the painting. It rather seems that Flinck wanted to surpass that of Van der Helst from 1639, and if his talent needed a greater master to inspire him it was rather Van Dyck than Rembrandt.19

Because the painter was subject to the measurements of the wall space where the painting was destined to be placed, it is, contrary to most civic guard paintings, higher than it is wide. The attention is drawn first to the powerful features of the lieutenant in a yellow tunic with a blue-green sash, who bending forward with drawn partisan addresses two officers, seated on chairs lined in red and with curled legs, such as we have already encountered on the Four Burgomasters by De Keyser.20 One of the gentlemen, whose lush, gray strands of hair come from under a black, plumed hat, is dressed stylishly in black velvet. The other one is dressed in a silvery satin, with a heavy orange sash. The latter wears yellow shoes and a white hat. Both gentlemen wear their rapiers on the side and hold canes in their hands, which inclines us to conclude that we see two captains in this painting, although Schaep only names Captain Bas and Lieutenant Conijn. Maybe the work was painted on the occasion of a change of captains. Schaep’s notes (probably from the proceedings of the war council) on the changes in the officers of the civic guard21 however lack these years. We do know, however, that in 1638 Jacob Simonsz de Vries was still the captain in district eighteen; but we cannot recognize this old man (whom we know from the painting by Thomas de Keyser) in one of the captains painted by Flinck. It is likely therefore that another person served as captain in between.

Above the officers a large orange flag is visible, decorated with a representation hidden in the folds. The ensign is dressed in gold brocade, with heavily split sleeves, white sash and a white hat. To his left, with his left hand on his chest, is a musketeer in a light yellow-gray tunic, the fork for his gun hangs by an orange rope from his left wrist; on his white hat is a blue plume. Obviously there is no lack of marvelous colors, although both pikemen to the right of the ensign are dressed in black. In the background, four more persons are descending a staircase with a richly decorated balustrade under an arcade of gray stone.

These are the civic guardsmen of district eighteen (the same company that De Keyser painted when De Vries was captain and Dirck de Graeff lieutenant). They lived on the Pijpenmarkt [pipe market], for example, Lieutenant Conijn, or opposite on the Deventer Houtmarkt [wood market], later the Bloemmarkt [flower market, both markets are presently part of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal], or on the first part of Kalverstraat or Rokin, such as Captain Bas, who in fact lived just outside the district on the southern corner of the Duifjessteeg. In the district itself there certainly was no better person then this patrician, who, a couple of years after Flinck painted him, became burgomaster and whose father had also held that office a couple of times between 1610 and 1637, the year of his death. That father was Dirck Bas, who was knighted in 1616 by Gustav Adolf as a reward for his mediation in the peace between Russia and Sweden, allowing him to move the white lapwing in his coat of arms to the left and adorn the right half with a white eagle holding a green olive branch in his beak, signifying peace.

If the art-loving citizens of district eighteen had given Flinck the occasion to show if he could improve on Thomas de Keyser, some years later his talent was even more tested when he was commissioned to paint the civic guards of the district that had recently been painted by none other than Rembrandt: district one. The men in that district had, however, changed completely in those six years; none of the names of the civic guards painted by Rembrandt appears on the list of names in Flinck’s work[fig. 5].22

In another way, too, Flinck had a competitor with this painting, someone with whom it was a great honor to be competing. His work that I am now going to describe was destined for the Old Hall of the Crossbow Archers Civic Guard Hall, as a pendant to the Meal of Civic Guards by Van der Helst23 and, just like this one, it not only had to be a portrait group but also had to have value as a history piece, for it had to express the joy of the Amsterdam citizens over the recent Peace of Munster. It was probably solved by friendly agreement that Van der Helst chose an interior for the depiction of the feast, and Flinck depicted the happy atmosphere in the street.

With a lot of tact, Flinck divided his civic guards into two groups. To the left, eight persons descend the low steps of a building which one can consider the civic guard hall itself; the captain is at the front, the ensign, following him, is still on the stairs, other civic guards are behind him in the door, while the sergeant, Appelman, is placed next to the steps with a couple of others, awaiting the captain, who, while facing right, turns his head to the left in greeting. This greeting is meant for the lieutenant, who, at the front of another troop of civic guards walks through the street and, when both have gone a couple of steps more, will join the captain on his left flank and march with him at the head of the troop.

The background of the group on the left side is formed by the dark mass of the building from which the civic guards appear. The right group is set off against a cloud of smoke formed by the shots of joy fired by the musketeers accompanying the lieutenant and by the burning tar barrels, which stand in line behind them on the far right of the painting..

The connection between both main groups is formed in a fortunate (or unfortunate) way by a civic guard from the group led by the lieutenant. This lieutenant makes use of the moment of standing still to pull up a stocking that had sagged, placing his left foot on one of the steps. I said in a fortunate or unfortunate way because, however fortunate the idea is to obtain an elegant wave in the line of heads by the stooping posture of this person, and however drawn from life this episode might be, this unabashedly prosaic act clashes with the genteel and graceful postures of the other figures. They pose so impeccably that their postures have been denounced as mannered in the past. Some have even asked in joking exaggeration about which professeur de maintien [professor of poise] taught our old Amsterdammers such elegant steps. Do not forget though, before blaming the painter, that in the seventeenth century, a civilized education valued much the effort put into dancing and fencing. Assuming a calculatingly elegant pose cannot have been so unnatural and forced as it seems to us nowadays.

Anyway, Flinck has succeeded in really giving space to his figures and breathing air into his painting. And although the tone is less warm then in his painting of 1645, and although his works do not pluck the strings of our hearts as they do when we stand in front of Rembrandt’s civic guard painting, nevertheless Flinck’s work holds its own well opposite [Van der Helst’s] Meal of Civic Guards and every individual portrait is treated outstandingly.

We therefore can best look at them one at a time. We do this with all the more attention because this is the only civic guard portrait in Amsterdam that identifies each person with a tiny number on the painting, corresponding to a list of names that has been preserved.24

This is how we know that the man with the jackboots, pulling up his stocking, is Pieter Meffert,25 and that the fat little man who has taken a seat and removed his hat — warm and tired as he already is from the march — is the portrait of Mr. Albert ten Brink (the innkeeper of the Oudezijds Heerenlogement). It [the list] also identifies the musketeer with the plumed helmet, who loads his gun behind the lieutenant and whose figure seems a bit badly drawn (rare with Flinck!), as Johan van der Hoog, or Van der Haag.

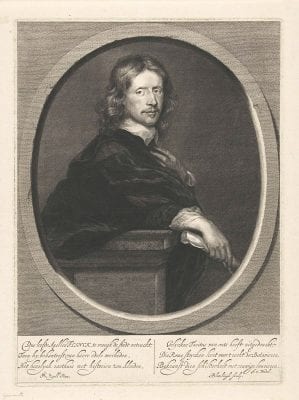

It is more important that the painter himself also appears in the painting, among the men coming through the door. Not as a civic guardsman, though, because Flinck not only lived in another city district (on the Lauriergracht) but he was not yet a citizen of Amsterdam (he registered as such only in 1652). His weak and pale appearance betrays the constitution that only affords health on the condition of “taking care of oneself.” The features correspond with the portrait painted by Gerard van Zijll, whom Blooteling and Vaillant brought into print [fig. 6].

The sergeant in the group on this side, on the far left of the painting, is Jan Appelman.26 This plain name would not suggest that he is the head of one of Amsterdam’s oldest families, whose forefathers already occupied city offices before the Reformation, when they lived at the entrance of Nieuwendijk, next to the old town hall. Nor does the portrait that we see before us here — of the relatively soberly dressed young sergeant with his long hair and cheerful features — answer in our imagination to the fearsome Amsterdam burgomaster, who, although brought into the council in 1672 by Prince William III himself, later became one of the staunchest adversaries of that prince and his servants. Even the preparations of the assault on England in 1688 had to be kept a secret from him, at the time when they were being drawn up by his fellow burgomasters. Later he became the “black sheep” of the Orange party, to such an extent that he was depicted in cartoons as “barsse Jan” [Surly Jan] who “started to stir in the drunk company at the Arquebusier civic guard hall” courting and being bribed by the French king [fig. 7].27 It is a shame that [Jacob] Houbraken, instead of Flinck’s civic guard sergeant,28 did not know or choose the portrait presently adorning the museum in Haarlem, when he engraved the portrait of Burgomaster Appelman, for the illustration of Wagenaars Vaderlandsche Historie [fig. 8]. The latter painting gives such a favorable testimony of the abilities of our Amsterdammer Jan Victors as a portrait painter.29

The other sergeant, in the opposite corner of the painting, is Jacob van Campen,30 not the architect of the Amsterdam town hall as was believed in the previous century, to the dismay of Van Dijk,31 but his cousin, the brother of the graceful Machteld van Campen who enchanted Huygens on Tesselschade’s wedding, but who in May 1626 was plucked from the stem like a flower withering too early.32

Van Campen has taken his plumed hat off, like the other officers who salute each other courteously, while the other civic guards keep their hats on. His dark attire accentuates the dashing robes adorning Lieutenant Frans van Waveren standing in front of him, whose clothing competes with that worn by his brother, the ensign Nicolaas, who descends the steps with the white standard. Both brothers are sons of the dignified burgomaster Anthony Oetgens van Waveren. Claes later married Burgomaster Willem Backer’s daughter and became an alderman in 1665;33 the lieutenant [Frans van Waveren] died unmarried and without occupying an office. Their older brother Johan (the later burgomaster) is the lieutenant in the Meal of Civic Guards by Van der Helst.34

Let us finally focus our attention on the main character: the captain. Flinck paid much attention to his beautiful head. His heavy-set stature gives the impression that he is acting like one of those self-conscious, energetic burghers, never daunted by even the heaviest burdens of government worries, someone whose determination did not bend even under the most overwhelming torrents of problems. He appears to have been one of those burgomasters who did not work hard to enrich themselves but did it for their citizens, and on whose watch one could safely sleep at night. That sort of personage raised Amsterdam to a city admired by the whole world. Those regents, while disdaining comfort and splendor for themselves, belittling their own pleasures, were not indifferent to literature and art. They were plain and frugal by nature, but loved grandeur, aware of what their rank asked of them. Thus appears before us, both in history and in Flinck’s painting, the image of Johan Huydecoper van Maarseveen, the main character and the principal protagonist in the depiction. He is identified as such by the lines of Jan Vos’s poem, which were originally legible on a painted piece of paper that seemed to have been inserted between the frame and the painting (they have now been mostly erased by time):

Hier trekt VAN MAARSSEVEEN de eerst’ in d’eeuwige vreede.

Zoo trok zyn vaader d’eerst’ in t’oorlog voor de Staat.

Vernuft en Dapperheidt, de kracht der vrye steede’,

Verwerpen d’oude wrok, in plaats van ’t krijgsgewaadt.

Zoo waakt men aan het Y na moorden en verwoesten.

De wyzen laaten ’t zwaard wel rusten, maar niet roesten.

[Here VAN MAARSEVEEN leads in eternal peace.

As did his father lead in the war for the sake of the State.Wit and bravery, the strength of free cities,

Reject the old resentment, instead of the armor.

This is how they keep watch at the IJ [river] after murder and ruin.

The wise let the sword rest, but not rust.]35

That father was Jan Jacobsz Bal van Wieringen36 with the nickname Huydecoper (probably deriving from his profession, a reference which appears in the three ox heads on his coat of arms as well).

That he was a man in whom one could trust is proved by a particularity noted in the family chronicles of the De Graeff family: Dirck Janszoon de Graeff, when he fled to Emden, sent ahead two iron cases with 60,000 guilders to Jan Jacobsz Huydecoper, who had earlier fled the Spanish violence.

That he, too, had fought the Spanish appears from another poem by Vos,37 and also from one other fact. During the Alteration of 1578, he headed the company that was the first to keep watch under the slogan “Oranje” — he was soon promoted to the rank of colonel of the civic guards. He also helped to govern the city as councilor, alderman, and treasurer and died on April 20, 1624. His marriage to Elisabeth van Gemen seems only to have taken place when he had reached an advanced age. As someone who fled the country in 1567, he must have been at least sixty in 1601 when the son was born that we now see before us.38This helps explain the peculiar fact, mentioned by the poet in the verse on the painting that the father helped start the eighty-year war and the son helped end it. In all likelihood, the grandsons of those men of 1567 were now governing the city, while the sons had already passed away. Huydecoper, however, still had a glorious career ahead of him, although in the year in which we meet him, he had already gained multiple honors. After his short-lived first marriage to Elisabeth Pietersdochter Biscchop (1621), in 1624 he married Maria, a daughter from the rich merchants family Coeymans or Coymans.39 In 1629, he was first appointed alderman and in 1630 he joined the council. Around 1638 he was knighted by Christina of Sweden and also bought the manors of Blokland and Thamen. He traded that title a couple of years later for that of lord of Maarsseveen and Neerdijk. In 1640, he bought Maarsseveen, opposite the village of Maarsssen [on the river Vecht], a region that had already become charming to rich Amsterdammers, who gladly built their country houses there. After the period when Huydecoper lived there in his country seat Goudesteyn (still existing today), it flourished even more. Therefore, the delighted inhabitants of Maarsseveen festively welcomed their new lord on August 13, 1641, and honored him with a beautiful cup. An etching by the little known artist Hendrik Winter recalls that occasion [fig. 9]. From that year onward, Huydecoper proudly adorned the heart of his coat of arms with the black pig of Maarsseveen. But these noble titles did not incline him to neglect trade and shipping, neither in his own business, nor in that of the East India Company, where he served as a governor. Just as energetically, he continued to attend to justice in the college of aldermen. But also the civic guards demanded his service and when Banninck Cocq became colonel, “Amsterdam, full of rivers and gold” seemed “drowned up to the stars in a sea of smoke and fire,” from all the shots of joy that were fired when Huydecooper served as the captain in district one.40 He lived there, in the house on the Singel near the Vijzelstraat,41 one of the more beautiful buildings by Philips Vingboons, which nowadays is still a gem in our town, with its system of pilasters and its neatly cut hardstone gable and which we see depicted in the background of the painting by Flinck [fig. 10, fig. 11].42

Shortly after the peace celebrations of 1648 the pikes and muskets of the civic guards nearly had to be put to use. The martial qualities would have been tested had the militia sent by Prince Willem II advanced and surprised rebellious Amsterdam. But the diplomatic skills of Huydecoper proved even better than his martial qualities. After having helped Burgomaster Bicker in bringing the city quickly into a state of defense, he participated in negotiations held at the manor Welna, convincing the commander of the stadhouder’s troops to refrain from violence. Grateful Amsterdam entrusted Huydecoper with the honor of becoming burgomaster and in 1654 he became a member of the Council of the Admiralty in Amsterdam. The most glorious year in his life was 1655, however, when he was delegated to represent the city in Berlin at a solemn embassy for the baptism of the son of Louise Henriette, Frederik Hendrik’s daughter. For political and financial reasons, the city took great interest in its friendship with the Brandenburger and accepted the godfathership over the newborn. Huycedoper brought the christening gift, a letter of interest worth 1,000 guilders per year in a gold box. The ivory head, made by the elector himself, that Huydecoper received, served as a proof of the prince’s particular satisfaction. Moreover, the prince had an especially friendly relationship with Huydecoper. He had dined at his home and Huydecoper’s daughters were honored with gifts by the prince’s wife (when she visited Amsterdam officially in 1659).43 But the Amsterdam citizenry was also pleased with the embassy. A gold coin,44 presently kept in the collection of the Royal Antiquarian Society, was engraved. And one of Huydecoper’s former officers in district one led the horse guard of honor when the burgomaster was welcomed upon his return from Berlin with an almost regal triumphal entrance.45

No less happy a day came for our Huydecoper some months later when, on July 29, he and his fellow burgomaster took their seats in the finished town hall. This was the monument that displayed the glory of Amsterdam to the whole world. He had contributed a great deal himself. As appears at a certain point in Vondel’s Inwijding van het Stadhuis he had been a member of a commission, drawn from the council at the time, that prepared the work and chose the best design.46

In that commission, did Huydecoper choose the design by Vingboons, who built his house on the Singel, the rival design of the one by van Campen? We do not know, but there is no reason to suppose so, because Huydecoper was not a man whose love of the arts was characterized by one-sided preferences. Did he receive Vos’s poems in his honor with the same affable smile as those by Vondel? We have seen that he sat for his portrait to Flinck and Van der Helst, yet he also let Jonson van Ceulen portray him.47 Jan Lievens portrayed his son.48 And many different artists were allowed to decorate the rooms of Goudesteyn and the house on the Singel. The subjects of those paintings, mostly derived from antiquity, are somewhat too academic for our [current] taste. From this [academic taste], it is possible to determine the directions needed to please patrons of that time. Flinck was present in the gallery at Goudesteyn with his representation of Lucretia. Our burgomaster was also interested in sculpture, judging from the fountains and statues that adorned the gardens and vestibules, both in his country house and in his home in Amsterdam. Quellinus also sculpted in marble a life-size bust of the burgomaster in 1654 [fig. 12], for which Vondel wrote muscular verses. Nowadays it can be found with Huydecoper’s descendants at Goudesteyn,49 where Huygens admired it in 1656:

De lieffelijke locht in allerhande weer

De klaerheit van den stroom en ’t blanck hert van den Heer50

[The gentle air in weather of all sorts

The clarity of the stream and the fair heart of the Lord]

What deserves special mention is that the lord of Maarsseveen not only showed himself a Maecenas in the sense of buyer and connoisseur of art, but he also demonstrated a humane and friendly way of dealing with artists. We know this from the fact that despite his position as a dignified and powerful burgomaster, he did not deem it below his rank to join the well-known feast of the guild brothers of St. Luke in the Crossbow Civic Guard Hall in 1654. This was where Vondel celebrated the art of painting in his poetry, in thankfulness for the honor bestowed upon him the year before, when he was crowned by Apollo with laurels as the “head of the poets,” in the name of the assembled painters.51

Govert Flinck was probably present at those festivities, though he did not play a big role there. The first, as well as the latter, appears from a rhyme that father Vondel wrote when the noisy artists were making too much of a bustle for his taste and the wine from the cellars of the civic guard hall went to the guests’ head all too much. He shoved it over the table to a certain Govert, without doubt our painter, who produced more than one portrait of the poet in these years.52 They probably left together, because Flinck seems to have been a quiet and homely man, even if he did not, as is usually supposed, belonged to the reserved Mennonites.53 All that we know of him shows that he was committed to a quiet and comfortable domestic life. He was not a man to spoil the esteem that high-ranking persons had of him by an irregular lifestyle,54 not only with the regents in the city he lived in but also the sovereigns that ruled his native city in succession: first the elector of Brandenburg, later Prince Johan Maurits of Nassau. His visits to Cleves and the circumstance that he left behind there after his death strengthen the argument of his attachment to the place where he spent his childhood and to his family remaining in that region.55 In Amsterdam, however, he made his money; he was well paid and used his fortune like an honorable citizen but also as a civilized man.

He had bought two houses on the Lauriergracht (north side), with a shed and garden, running to the Laurierstraat, and he showed off carpets there that were given to him by the elector of Brandenburg and the sculpture by Quellinus that he had collected.56 Twice he led a wife into that house, both times a woman from the south of Holland from a good family.

On June 3, 1645, he signed his vows in the presence of his father, Teunis Govertsz Flinck, with the twenty-five-year old Ingitta Thovelingh from Rotterdam. Her mother, Maria Dircksz Bos, acted as a witness to the bride, probably the widow of Claes Martensz Thoveling, who was governor of the East India Company in Rotterdam and whose portrait can be seen in the [Rijks]museum in the courtyard with the maritime collection. The widow lived on the Singel at the time, yet six years later we find her on the Lauriergracht next to the Walenweeshuis so perhaps in the house of her son-in-law. This is not certain because her own son, Marten, was unmarried and could also have lived on the Lauriergracht.57

Already in the next year Ingetje gave Flinck a son, who received the names Claes Anthony. Flinck’s marital happiness soon came to a sad end, however, by a miserable disease that his wife had already contracted before they married, although she was not very burdened by it and remained cheerful and strong. In the end it worsened so much that death was the final result. She had a swelling (an ovarian cyst) of such dimensions, that her case has been described in medical science as a curiosity, among others by the famous Tulp in his Medicynsche Aenmerkingen. The city doctor Job van Meekeren described the process of the autopsy58 that occurred on January 5, 1651, and for which the patient had given her consent. The water drawn from her monstrously swollen abdomen weighed more than 100 pounds!

Havard, who translated Van Meekeren’s report, concluded that Ingetje had already suffered from the disease before the marriage.59 He added that she belonged to the upper class and that, since Flinck had mortgages on his houses in 1644, it is doubtful whether Flinck’s first marriage was motivated by love. It is a pleasure for me — as a result of of Mr. Abraham Bredius’s kindness — to offer proof that Flinck did not need to marry a sickly wife for her fortune. This appears from Flinck’s testament, made before the Amsterdam notary J. van Loosdrecht, together with the prenuptial agreement, signed June 2, 1645. From this agreement it becomes clear that Govert Flinck brought f16.000 into the marriage, represented by the houses on the Lauriergracht and by paintings, prints, and many other things that belong to the art of painting, while the bride brought in f6.000 guilders in cash and interest letters [documents indicating the right to an annual income of interest from a sum of money]. If the man had died childless, his bride would pay his heirs f10.000; if the opposite, Flinck would be held to pay f4000, to the Thoveling family. It is clear: this is not a case of a poor painter marrying a rich girl after all!

On April 19, 1646, the prenuptial agreement was replaced by a testament of the married couple, not because of the sad health conditions of Ingetje after the child’s birth, as Havard thought, but because of her pregnancy. In the will, the child or children were proclaimed heirs, excluding usufruct, guaranteed to the surviving parent. In addition, it specified a payment of f5000 to the testate’s family, if he [Flinck] died first, and f2000 to be paid by the widower to the family of the wife, if she should die first.60 Flinck adhered to this testament when on May 23, 1656, he secured f10.000 for his ten-year-old son (who would be given a stepmother), for his mother’s share, as Havard published from the archive of the orphan chamber.61

Maerten Claesz Thovelingh, the brother of the child’s mother, acted as guardian. He himself had declared the child to be his universal heir in 1652, except for a bequest of f1500 to the children of Govert Crabeth in Gouda.62 From the latter, it appears that the Thovelingh family also had relations in Gouda and therefore it is not improbable that we may see a relative of Flinck’s first wife in the woman from Gouda, Sofia van der Houve, whom Flinck took as his second wife on May 30, 1656.63 If we are to believe Vondel,64 who recited a poem at the wedding, many a Diana or Magdalen who left Flinck’s workshop at that time involuntarily revealed features if his beloved Sofia.

How happy must the artist have felt that, precisely in that year,65 he could paint the allegorical figure after which his chosen had been named: the heavenly Sophia, divine wisdom. The Amsterdam regents, who were not ashamed to demonstrate that they did not hold human intelligence for the highest in the universe, wished to see painted in the council room in the new town hall, the daily example of Solomon’s prayer for wisdom [fig. 13]. Flinck also depicted Wisdom descending from higher spheres because of Solomon’s prayers. But his work was not happily inspired. His Wisdom is anything but an ethereal figure: nothing more than a woman seated on clouds, illuminated by a cold and soulless light. The kneeling Solomon is more successful, and the groups of surprised priests and Levites are brought into the painting expeditiously as filler, without distracting too much. But regardless, the painting leaves us indifferent; it is languid and without exaltation. No trace left of the deep feelings, nor the ingenious originality of the artist who had once been Flinck’s teacher — no trace of his firm grip nor the fantastic light with which he [Rembrandt] would have painted such a subject. In the last century, Van Dijk praised the work as Flinck’s masterpiece, especially because the artist had given Solomon a golden robe and none of the three colors that, on God’s order were consecrated: purple, scarlet, and heavenly blue. He understood well that these three colors were not fit to adorn persons other than the high priest.66 We admire the painter’s good understanding, but we also understand something else: when the artist limits himself by such eloquent pettiness, Dutch art rushes towards speedy decadence.

Flinck’s patrons, however, were very satisfied and paid him 1,000 guilders as a reward. We do not begrudge him the wage, but where we see him carry the heavy purse with gold to his well-furnished house on the Lauriergracht, we cannot suppress a sense of melancholy if we think how such a sum might have benefited the bankrupt genius who in that very year had to sell his house and art treasures at a public auction resulting from his financial troubles for which, as a nation, we feel still ashamed.67

Flinck painted yet another large canvas for the town hall: one of the chimneypieces in the burgomaster’s room. It was probably painted before the Solomon, because the friezes in the burgomaster room had already been made in 1655 by Quellinus. In this painting, for which he received f1500,68 Flinck depicted how Marcus Curius declined the offered gold and his contentment with a meal of turnips [fig. 14]. In this painting, too, we admire the rich and judicious composition, a meticulously good line and a correct division of colors, in addition to a well thought-out expression of the contrast between the proud simplicity of the solemn Roman and the luxuriant appearance of the envoy, who wants to enable him to enjoy all the goods of the earth. There is much in the painting reminiscent of Rubens, but it lacks the glow and strength that inspired the great Antwerper.

Similar work by Flinck would have been visible in the town hall had death not surprised him. In November 1659, he received a commission for twelve scenes, for f1000 apiece, to fill the lunettes in the vaults of the high galleries, or corridors, which, adjacent to the large central hall, run around both courtyards of the building and that nowadays are fragmented and separated from the central hall by wooden walls. Each year he was to deliver two of them. But before even one was finished, a short but fierce illness brought the painter to the grave (February 2, 1660) at the age of only forty-five years. This was without doubt too early for his family, but not too early for his fame — although it is exaggerated to characterize him as “in the end deteriorating into an Italian fake [style].”69 A beautiful burial-coin was made in his honor [fig. 15], one that has served as an example of such coins into our own century. It is depicted in Havard70 and in Van Lennep’s Vondel,71and it is present in the royal numismatic cabinet in The Hague.72 Although the inscriptions are engraved, the careful workmanship and its unusual type indicate that we are not dealing here (as usual) with a coin that a goldsmith had in stock and could engrave as required. This is a piece that was made especially for the occasion.

Like Rembrandt and Van der Helst, Flinck left one son.73 This was Nicolaas Anthonie Flinck, whose birth I mentioned above. And just like Titus van Rijn and Lodewijk van der Helst, Nicolaas Flinck was skilled in the arts. This is apparent from an etching, in the Rijksprentenkabinet, which owns one of the rare impressions: a portrait of a young man with long hair, signed “N. Flinck fecit (de N and F ligated)” [fig. 16]. It is considered to be his own portrait and the family resemblance makes this very likely. Little evidence indicates that the young Flinck had dedicated himself to the arts other than as a collector.74

After his father’s death he seems to have moved with his stepmother to the south of Holland, to join her family and that of his own mother. In the beginning of the next century, we find him back in Rotterdam en grand seigneur, in a beautiful house (presently the Hotel des Pays-Bas, in the Korte Hoogstraat, near the Passage),75 serving as a governor of the East India Company and married to the burgomaster Van Berckel’s daughter. He gave Arnold Houbraken (not always correct) information regarding the biographical facts of his famous father. He owned a fairly good cabinet of paintings, partly left by Govert, which after the death of his only daughter was auctioned in Rotterdam on November 4, 1754.76

Flinck’s protector, Huydecoper, soon followed him to the grave (October 26, 1661). He had lived through some happy years: in 1658 he had been treasurer and in 1659 and again in 1660 burgomaster. His only son Jan, who was born in 1625 and studied in Leiden in 1645, became an ensign (later lieutenant) in the twenty-eighth company, where his father was captain.77 He accompanied his father to Berlin in 1655, married Sophia Coymans, his niece, after his return, became an alderman in 1656, and burgomaster in 1666. Regarding his sisters, the two eldest, Maria and Leonora, both married members of the Hinlopen family in 1642 and in 1657. The four others were still unmarried at their father’s death and the house-poet Jan Vos, as an affably received guest, could sing of the beauty of Geertui,78 the homely care of Constantia,79 the erudition of Elisabeth,80 and the youth of Jacoba Sophia,81 until he too paid the toll of nature in July 1667.