This fourth installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits focuses on works by Thomas de Keyser and Joachim von Sandrart (Oud Holland 6 [1888]: 225–240). Meijer’s article was originally published in five installments in the first few issues of the journal Oud Holland.For translations (also by Tom van der Molen) of the first two installments, see JHNA 5, no. 1 (Winter 2013). For the third installment, see JHNA 6, no. 1 (Winter 2014).

Thomas de Keyser

Among the artist-families that flourished in Amsterdam in the Golden Age of the first half of the seventeenth century, the De Keyser family deserves first place.1 The head of the family was Hendrik de Keyser, the architect and sculptor, who was born in Utrecht. After having moved with his teacher Cornelis Bloemaert from Utrecht to Amsterdam, he married Beyken Pietersdochter van Wilder there in 1591.2 In his new residence he soon acquired the esteem and trust of the government and notable burghers and received many commissions, of which Pieter Cornelisz Hooft, when still a student, predicted — what became so literally true — “the nation will use your works as the main witnesses to its descendants of its present happiness.”3

When he died, on May 15, 1621, Hendrik de Keyser left four sons. The youngest inherited his father’s first name, but the three oldest became the heirs of his artistic nature. The oldest, Pieter, finished the tomb of Prince William I in Delft, started by his father. Since he was a city stonemason in Amsterdam, it was probably he who delivered the designs for the city’s buildings erected in the time of Prince Frederik Hendrik: the Heiligewegs-, Antonies- and Nieuwe Regulierspoort, the Staalhof,4 the Arquebusier civic guard hall, etc. Kramm5 mentions that he was the teacher and father-in-law of the sculptor Nicholas Stone, who is famous in England.6

Willem de Keyser, the third son, worked primarily in England, where he probably died. We find, however, from 1642 to 1652 mentions of a Willem de Keyser as a stonemason in Amsterdam. In 1647, he was appointed city stonemason after that office had been vacant for some time.7 Pieter de Keyser had therefore not held the office until his death, as he was still alive in 1654.8 Willem died perhaps in 1653.9 In any case, in that year Simon Bosboom10 took his place. Bosboom is known because he collaborated on the Town Hall and published architectural books.11

Hendrik de Keyser’s second son, Thomas, who according to De Bray was also very skilled as an architect,12 chose the art of painting, and his portraits aroused the ever-increasing admiration of the generations after him. Even still, in a curious way his name had almost lost its immortality. At a certain point his usual signature Th. was read as Theodorus and after that the mistake was repeatedly copied, up until recently when the correct first name was done justice to again.

Of the works by Thomas De Keyser that we are able to date, the earliest is the one that was commissioned to him in 1619 [fig.1],13 when the upper floor of the St. Anthonispoort — which had been rebuilt as a weighing house — was furnished as a “Snijburg” (dissection room). The prelector Dr. Sebastiaan Egbertsz (afterwards burgomaster) had himself depicted, with four [sic]14 of his students, while demonstrating a skeleton. It was commissioned to adorn the chimney. This anatomy lesson is nowadays on display in the Rijksmuseum, formerly no. 185d, now no. 766.15 Two years later De Keyser made the portrait of his famous father that was engraved by Jonas Suyderhoeff and honored with an epigram by [Joost van den]Vondel [fig. 2].16

The same poet dedicated some lines to a portrait of the former Governor-General Laurens Reael by De Keyser.17 Until now, it has been assumed that this portrait was the life-size, full-length depiction that is presently in the collection of Johanna E. Backer, née de Wildt, together with the matching portrait of Reael’s wife, Susanna de Moor. They were considered to be among the greatest gems of the Historical Exhibition [Historische Tentoonstelling van Amsterdam] in 1876.

Now that the notes by Arent van Buchel have been published, however,18 we can conclude with some confidence that it was Van der Voort who painted the portrait of Reael “tot de voeten” [down to the feet, meaning full-length]. In fact, I have my doubts that the portrait that De Keyser made — the subject of the poem by Vondel — is the one that [scholars] have considered it to be. On the contrary, as Mr. Six mentioned to me,19 we must consider the work presently owned by Mrs. Backer to be the one painted by Van der Voort that Buchel mentioned.20 Mr. Six has also denied authorship to De Keyser of the Portrait of Marten Rey, ao 1627, in the Rijksmuseum,21 and rightfully so as this connoisseur states that among the paintings attributed to De Keyser, particularly those in foreign museums, there is need for further sorting.

How happy we are to own two works by Thomas, works that are really by him beyond a doubt, from 1632 and 1633. They are the civic guard portraits that currently adorn the Museum’s Hall of Honor (to the right): nos. 767 and 768 (formerly 185 e and f) [figs. 3 and 4].22 The first of them is the older and immediately appeals to us through a general tone that is so much warmer than in civic guard portraits by other masters produced only a few years previously. Here the eye is regaled not so much by the richness of colors that shine in the paintings by Van der Helst and Flinck as by their silent harmony. Also it cannot be denied that the grouping aims for naturalness and ease. De Keyser placed his main characters on a slight rise: the upper step of the entrance to a building. The spectator can imagine himself in the front door of that building. Because the officers remain on the highest step and other civic guardsmen have already placed their feet on the lower steps of the entrance, one receives the impression that in the next moment a collision will take place in that small space, because the space could never contain all these persons.

To the right and to the left, other civic guards stand in the background. Here perspective has been applied more strongly than usual in civic guard works, causing the portrayed to appear smaller than those in the foreground, even somewhat smaller than needed for the distance where they stand, when we compare it with the perspective of the background.

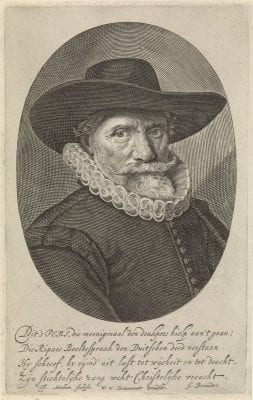

For one of those persons on the second plane I want to give some extra attention: the oldest of the two civic guards stands on a higher level at the left. From the list of sitters that is still visible on the painting, it appears that Dirk Pietersz. Pers is depicted. And it is thanks to an etching by Dirk Matham after this head [fig. 5], that we can identify in the top left corner, the serious, pensive face of this poet-bookseller, born in Emden and named after the “white press [witte pers],” the sign of his shop, which he had started in the first years of the century on the Damrak, opposite the grain market.

It was there that Vondel’s Gulden Winckel and Warande der Dieren were published. And it was there that songbooks were sold: Nieuwe Lusthof, Bruylofts-Bancket, Bloemhof van de Nederlandse Jeught, Bloeiende Mey-waghen, Apollo of ghesangh der Musen, in which Hooft and Brederoo, Coster, and Heinsius offered their first writings. Nowadays these are viewed as precious relics for the study of our literature. Later Blaeu became the favorite publisher of the poets. According to a verse on Pers, Vondel seems to have blamed Pers for being more self-interested than other writers.23 It was perhaps to avenge himself or because his business now gave him more time to play the lyre himself, that he first put Historien van Lucretia en Scipio (1624) into rhyme.24 Afterwards he fought the abuse of wine [het misbruycks des Wijns] (1628),25 published a poetic extension to the book of Jonah (1635),26 and finally his Bellerophon.27 The Bellerophon (1614) was praised by Cats, who was Pers’s model. With that work he made a name for himself as a moral poet and lyricist for the first time (the work had two sequels). He shows his considerable literacy in writings that are often ornamented with important prints (Jonas de straf-prediker,for example, has a title page after Hans Bol). As an insignia, he printed a Christian knight on the title pages of his works, with the words “Ick strii op sno eerde” [I battle a wicked world], an anagram of Dirck Pieterssoone.28

It is not possible to introduce more civic guards by their names to the reader. Even if we know their names, thanks to the list that has been painted as a note, torn in two and partly inserted behind the frame, we cannot connect these names to the different [depicted] persons, because we lack any further hints. The exceptions are the ones that we can point out because of the signs of their rank as officers. The captain, in his strikingly simple, brown clothing, is the alderman Allard Cloeck. The lieutenant, in greenish gray is Lucas Jacobsz. Rotgans. The latter owed his rank to a small coup d’etat, that Schaep recounts in his notes: “30 June 1620 the burgomasters Pauw, Hoyng and Frederik de Vrij” (the counter-remonstrants) “overruling” (the fourth burgomaster) “Gerrit Jacobsz Witsen, had the war council meet at an unusual time, being 8 o’clock in the morning, and, on top of that, had [not] summoned all Captains and Lieutenants, but only some of them and some of them an hour later. And they have then deposed the 2 Lieutenants Nanningh Florisz Cloeck of the third regiment and Jan Claesz Vlooswijck of the fourth regiment, because of some frivolous addresses and particular objections to Burgomaster Pauw and immediately they have chosen two others instead of them, being no. 4 Arent Pietersz Verburgh and no. 3 Lucas Jacobsz Rotgans.”29

Those days are long past in this painting, however. After the reaction had taken place, a subject on which Mr. Gebhard has published in the first volume of this journal,30 the old disputes in the city district three, it seems, were forgotten, because [in the painting] Rotgans has kept his position, but he now has the son of the man he displaced on his side as the captain.31

Later they could even act as brothers-in-arms, because, on the occasion of the siege of Maastricht, two burgher-captains, Willem Backer of the 17th regiment and our Captain Cloeck of the third [the regiments were not entirely composed of their own company, but assembled with civic guards from various companies] went to Nijmegen to occupy that city. They departed on August 27, 1632 and stayed until October 6.

It would hardly be strange to conclude that the (bloodless) expedition was the occasion for commissioning this painting, dated 1632. This was, however, not the case after all.

This became clear to me from the discovery that A. D. de Vries made in the Albertina in Vienna, where he found a pen drawing (attributed to Van der Helst) that appeared to be the original sketch for De Keyser’s painting.32 It is dated “1630, 27 NOVEB,” from which it can be concluded that by then the painting had been commissioned from De Keyser (Cloeck was appointed captain in that year). The sketch is peculiar from another point of view as well, because it shows an important variation. The central group of six persons standing on the steps or mount are the same as in the painting, but both the five civic guards on the right-hand side and those on the left-hand side are grouped in a different way. The grouping of the sketch is much looser and more successful, the figures are much less compressed in space. The painter has probably been ordered to make a painting of specific measurements. After that he could not execute his original composition but was forced to find refuge by placing a number of persons in the second row, somewhat higher than those in front, to let their heads rise above the others.33

De Keyser was apparently compositionally unimpeded when he painted his other civic guard portrait a year later: the civic guards of district eighteen.34 The militia depicted in that portrait, no less than twenty-three of them, are placed in different positions, some sitting, some standing, so that, although they are all in one line, monotony has been avoided. The splendid distribution of colors also contributes to this [liveliness], as it shows a harmonic interchange of light and dark costumes.

Moreover, the artist had the fortunate idea of breaking the line of heads by providing a glimpse of a backroom. The door that gives entrance to this room is in the rear wall, which contains the bases of giant columns. We are again looking at fantasy architecture (in contrast to other civic guard portraits, however, it is rather modest, again stressing the good judgment of De Keyser). The backroom, with its beamed ceiling, resembles a room in the civic guard halls. Two civic guards appear there playing cards on a drum.

This painting has been ranked above De Keyser’s other civic guard painting by connoisseurs. Nevertheless, it contains a peculiar weakness of which I cannot keep silent: the majority of the persons depicted show a strange facial feature. It is apparent especially when one is on the same level as the painting (as used to be the case when it was in the third-class wedding hall [of the town hall], and in the first months after the opening of the new museum, when it was in the Rembrandt room). Because of that feature the portrait has been dubbed the “Jodencompagnie” (Company of Jews). Knowing that the civic guard companies are all inhabitants of a particular neighborhood, one would likely be inclined to search the eighteenth district on that side of the Sint Antoniesluis. Nothing however is less true: Captain Jacob Simonsz de Vries lived on Nieuwezijds Achterburgwal35near the Stilsteeg36 and his district included the Pijpemarkt and the Deventer Houtmarkt (the later Bloemmarkt),37 the Kalverstraat, and the Rokin, from Dam square to the St. Luciensteeg, and also the Beurssteeg etc.

Therefore no other conclusion is possible than a general design that the master involuntarily embedded into so many of the physiognomies. This, however, does not correspond well with the care that might be demanded of a portrait painter for a good likeness, and that might indeed testify to a rushed and careless finish. The brushstrokes too are different than on the civic guard portrait described above. The manner is masterful, but not exactly smooth. In many works by De Keyser one finds the broad strokes reminiscent of Frans Hals. In this civic guard portrait that is certainly the case. The following circumstance is very remarkable in that respect. De Keyser painted this work for the Crossbow Archers Civic Guard Hall (Voetboogsdoelen), and, according to Schaep, it was hung there in the “new hall,” together with works by Hals and Codde. The latter painting is dated 1637. However, while the painting may have been finished by Codde at that time, it could well have been started by Hals some years earlier (the officers depicted had already served together since 1632),38 and it is not unlikely that Hals received the commission in order to adorn the “new hall” at the same time that De Keyser received the commission for that same room. Might the contemporary work, maybe even hanging in the same place, have influenced the Amsterdam master, consciously or not? The genius from Haarlem was then at the pinnacle of his talent.

More expert people than I may decide this. The work by Hals, whether because it took too long to complete or did not please the Amsterdammers, was given to Codde to finish. As for De Keyser, after having delivered a civic guard portrait two years in a row, he was never asked to perform such a task again.

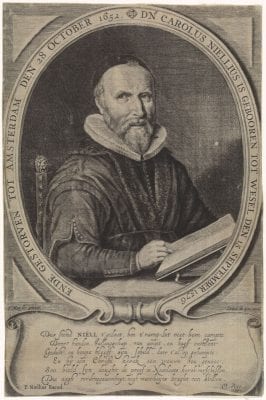

Yet this did not result from a deterioration of talent. Not according to our present-day judgment at least. In the next years, he still delivered portraits that inspire everyone’s admiration nowadays. And he remained in the favor of the best families in Amsterdam, particularly those of the liberal faction to which he himself belonged. De Keyser had joined the newly founded Remonstrant church. He “publicly” had his children baptized there, according to the baptismal register.39 In 1634 he painted the first minister of that congregation, Carolus Niellius [fig 6].40 From the same period come the life-size portraits of the later burgomaster Cornelis de Graeff and his second wife Catharina Hooft that are now gems of the museum in Berlin, after having long been in Huis Ilpendam, the manor of the De Graeff family.41 They are attributed to Thomas de Keyser, but his monogram (the interlaced letters T.D.K.) appears to be missing.42 They are also undated, but, since the second marriage of De Graeff occurred in 1635, they will not have been produced prior to that year. Since he had himself depicted with the old Town Hall in the background, they will not have been made earlier than 1636, because only in that year did De Graeff join the city magistrate. It was probably not so much his lack of talent that had kept him [from the city government], but the long lives of those family members that preceded him, with whom he could not serve simultaneously. One of Cornelis’s brothers had been depicted by De Keyser at an earlier stage. The lieutenant in civic guard portrait no. 768 (185f) is Dirk de Graeff, who passed away in the bloom of his years, in 1637, leaving behind a childless widow, Eva Bicker. She was the sister of Roelof and Hendrik Bicker. She was later remarried (in 1640) to Frederik Alewijn. I have recently exhibited her portrait (a masterpiece by Santvoort) in the exhibition of the Rembrandt Society in the rooms of the Antiquarian Society.43

In 1638, for the visit of the queen-widow of France Marie de Medici, who was received in Amsterdam with so much pomp and circumstance, Thomas de Keyser was granted the honor of painting the four burgomasters who received her. The portrait also included — entering the room and lifting his hat — the lawyer Davelaer, who was the commander of the guard of honor that escorted the queen [fig. 7]. This painting, currently in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague,44 has become widely known from the fine engraving that Jonas Suyderhoeff made after it [fig. 8]45 and also from the animated text that W. Burger (Thoré) dedicated to it, when he introduced De Keyser (then still called Theodoor) to the art-loving public of Europe in his Musées d’Amsterdam et de la Haye (1858) and thus placed him in the ranks to which he belongs.46 “The painterly touch is ample and firm, precisely where it has to be and only where it has to be. Simplicity, power, harmony, [all this one finds in this painting that is less than a foot high].” The characteristic conception and the breadth of execution particularly struck the French art lover, especially considering the small size of this work by the “unknown genius.”

The Four Burgomasters by De Keyser not only ignited the enthusiasm of the art connoisseur but also that of the historian, who sees immortalized another four physiognomies of men who were honored in Amsterdam during its heyday. It is a pity that confusion has arisen in the naming of the four depicted men.

The caption of Suyderhoeff’s etching naturally starts with the name of the presiding burgomaster, and, because the names are all on the same line, it is the one on the left. The painter, however, had placed this burgomaster to the viewer’s right and the others according to rank. The names therefore are the reverse of what has been assumed up until now. The portrait that was engraved by [Jacob] Houbraken (with the caption H. (sic) de Keyser pinxit) as representing Anthony Oetgens van Waveren, and that apparently represents the same person who in the painting is depicted sitting on the left of the person entering the room, therefore does not represent this burgomaster [Oetgens van Waveren], but his colleague Abraham Boom [fig. 9].47 The similarities to the likeness of the captain on the civic guard portrait no. 125 (former no. 74, now no. 826 in the Rijksmuseum) by Lastman and Van Nieulandt (that was described in volume 3, p. 120 of this magazine) cannot be denied, taking into account the sixteen years of age that Boom has gained by this time [of the portrait by De Keyser][fig. 10].48 The burgomaster behind the table is Pieter Hasselaer and not Albert Coenraedsz [Burgh], brewer in De Burgh on the Oudezijds Achterburgwal and former envoy to Moscovia and Denmark. The latter is depicted here en profil. One recognizes the witty head (showing off the optimism of the man who urged Vondel to continue his Palamedes), as he was engraved by Jacob Houbraken (this time with better luck!) after the civic guard painting by Van den Valckert. This was, at the time, attributed to Moreelse (the City’s no. 108, the Museum’s no. 1459), to which we will return later [fig. 11].

On drawings made after the painting or the engraving in the eighteenth century, the burgomaster seated in the right corner, signaling Mr. Davelaer to come closer, was thought to be Boom up till now.49

A seventeenth-century drawing in India ink in my collection, however, identifies the correct person: “D(octor) Anthony Outgens van Waveren, knight, Lord of Waveren, Botshol and Ruyge Wilnis,50 mayor and council, died 25 August 1658.” This drawing had brought A. D. de Vries and myself onto the right trail before; a notice in Schaep’s manuscript gave us the right placement of the persons depicted and although this painting is not a civic guard painting, I thought that noting it here would be of service to most of my readers.

As is known, the museum in The Hague can take pride in another masterpiece by De Keyser: the sitting man, who, with no reason known by me, has been catalogued as “magistrate.”51

After 1640, paintings by Thomas de Keyser became scarcer. Had he retired from the arts? Perhaps illness caused the decline? Or had he found a more profitable activity? Did he set too high a price for his talent? Behold some questions that until now have not been answered, not even by conjecture. The answers came from the notes that were made by Mr. de Roever in the city archives and put at my disposable with his usual friendliness. The year 1640 brought a great change in the life of Thomas. He apparently changed the brush for the chisel and the palette for office books, because, after having bought a plot of land with wooden sheds on the corner of Lindengracht and Brouwersgracht on April 16,52 he had himself registered as a stonecutter in the masonry guild on May 14, 1640, sufficiently satisfying “guild and moneybox”.53 Afterward he exchanged marriage vows with Aeltje Heymerichs, a woman from Deventer, with no parents nor money (apparent from the prenuptial agreement54) and living on Lindengracht as well, not unlikely a domestic servant. The marriage took place before a sheriff and alderman of Sloterdijk on September 9.55 The interests of Thomas’s son from his first marriage were taken care of well. His father’s testament in 1646 appoints as guardians, if necessary, Pieter de Keyser and the goldsmith Simon Valckenaer.

Thomas’s possessions extended along the Brouwersgracht until shortly before the Goudbloemstraat, therefore putting at his disposal a large terrain for his stonemasonry and trade in bluestone. In 1654, he was called a former bluestone-trader in a notarial document for a servant, and in the same year he sold his brother Pieter the plot of land with wooden sheds on the corner of Lindengracht for 8,000 guilders.

A rest in this business activity therefore probably allowed him to take up the brush again. That his talent had not weakened became apparent in the Portrait of Pieter Schout [fig. 12], later bailiff and dike warden (not lord therefore) of Hagestein, painted in the most impeccable color harmony, in 1660. In that year, the young jurist participated in the cavalcade that accompanied the entrance of the young Willem III and his mother. The monogram, as well as the handling of the brush, contributes to a secure attribution of this painting (engraved by A. Blooteling) to Thomas de Keyser.56

Because this work (along with the rest of the collection of the Van der Poll family) has been bequeathed to the nation, Amsterdam’s museum [the Rijksmuseum] now has the privilege of showing both one of the last paintings,57 and one of the first works of the master, the anatomical lesson. De Keyser died in the summer of 1667, aged seventy years old.

That is in any case how De Vries and Bredius noted it in their catalogue for the Utrecht museum Kunstliefde, based on the note in the burial registers of the Zuiderkerk of the burial of Thomas de Keyser on June 7, 1667. That Thomas de Keyser was a city stonemason, according to a resolution of the treasurers dated August 10, 1667, where his widow was granted a gratification. He had been appointed to that office by the burgomasters in April 1662 after the death of Simon Bosboom.

Is this city stonemason our painter — in his old days holding the office that had in the past been appointed to both his brothers successively? Or should we think of a younger member of the family here? — Thomas de Keyser had a son from his second marriage bearing his name who was engaged in this business, but he cannot have been this Thomas, because he died in 1679, after having baptized a son (Hendrik) in the Zuiderkerk in 1678 together with his wife Cornelia van der Kiste. This Thomas the younger, being born after 1640, is also too young for us think of him in relationship to a document, communicated to me by Mr. de Roever, in which a stonemason Thomas de Keyser transfers to his brother Hendrik half of the work taken upon themselves together from the treasury, to do the stonemasonry of the Oostindische huis (East India House), which was enlarged that year with a wing running from the Hoogstraat up to the gate of the Walloon church.

The Thomas mentioned in this document is probably the same as the later city stonemason; but again we are confronted with the question: is he identical with the painter of the civic guard portraits? It is not impossible, because this one, too, had a brother named Hendrik of whom we otherwise know little to nothing. The signature on said document is not the same as that of the painter on a document four years earlier, but does not differ so much as to necessarily put one in mind of another person.

The question could be answered soon if the name of the city stonemason could be encountered somewhere with his father or wife, but I haven’t succeeded yet.

The personal grave in the Zuiderkerk, in which the city stonemason was buried, brings us back to the painter’s younger years, when he lived on the Breestraat near the Anthoniesluis, in 1626, when he first married, and in 1629, when he bought a lined coat at an auction in the neighborhood for 20 guilders. Four days later he became the owner of a house on the south side of the Leliegracht for 5,600 guilders. When he later started his business on the Lindegracht, he seems to have cashed in his part of the family belongings on the east side of town. On February 10, 1642, Jacob Barrasa bought a house on the Houtgracht outside the Sint Anthoniespoort for 3,200 guilders from him (Thomas) and his cousin, the wood merchant Dirk de Keyser, the son of Aert de Keyser, who as uncle had been a witness at Thomas’s first marriage.

In any case, Thomas died before June 7, 1680. His widow survived him until April 1691. In addition to the son Thomas, who died before her, she bore another son, Pieter, born in 1646, who married Catrina Kliver in 1677. This Pieter was probably the city stonemason of that name, who had to exchange his office with that of overseer of the city masonry in 1683, after the city stonemasonry was abolished following a cutback.

Joachim Sandrart

When, in 1638 Marie de Medici, the queen-widow of France, was received so festively by the Amsterdammers,58 the hall of the Arquebusiers civic guard was new, and not yet decorated with paintings. No wonder that one of the companies, wanting to take charge of that decoration, thought to connect the memory of the widow of Henry IV to the portrait. She had been celebrated so magnificently and had so deeply impressed the citizens. The full civic guard had been present and there had even been a lot of quarrel among the captains over who would be first or last at the festivities and also over which location any of them would be present at and where or when they would march.59 In the end it was decided by a draw and Jacob Bicker with his seventh district was the lucky one who received the best place. That was on Dam Square, where the carriage had to halt for a moment to show the queen a depiction of her own marriage on a stage above the magnificent triumphal arch. On its top could be seen the Amsterdam cog ship, with a red silk flag on the mast. This company, therefore, would have had good reason to remember the festivities, where fate had been so favorable to them. But maybe Schaep was mistaken with the first name and the happy one was not Jacob Bicker but the other Bicker, Cornelis. However it may be, the painting expressing the civic guards’ enthusiasm for Marie de Medici [fig. 13] had been commissioned by Cornelis Bicker, the later burgomaster, whose name was so often mentioned in 1650 at the time of the attack by Willem II.60 At this point in time he was still captain of the nineteenth district, which extended from the Damrak between the Dam and the Zoutsteeg, running west to the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.61

The civic guards number around nineteen. I do not see the lieutenant Frederik van Banchem in the painting. May we assume that he, with gallant civic pride, refused to take part in the toadyism that greeted the foreign sovereign who would be the subject of this painting?62

The painter is Joachim von Sandrart, born in Frankfurt in 1606, pupil of the “court painter” Honthorst, who was so beloved in The Hague and a great admirer of Rubens whom he accompanied back to the border after he had visited Utrecht in 1626. Although he was Dutch by descent (his parents had emigrated from Bergen [Mons] in Hainault) and he fully followed the Dutch school artistically, Sandrart was a foreigner in the end, and one may justifiably wonder why the civic guards chose a foreigner at a time when the greatest masters were up for grabs in Amsterdam. They ignored Rembrandt and Van der Helst, Thomas de Keyser and Claes Eliasz, Backer and Flinck, and chose a stranger who was only temporarily in Amsterdam. The cause probably lies in the circumstance that Sandrart was a man of a certain class and education, eloquent enough to be pleasant to anyone, courteous enough to avoid bringing artistic whims to the foreground, and affluent enough to let the art lovers pay enough, but not to ask for money in advance. Using the pen as easily as the brush, speaking half a dozen languages, later sporting a noble title, he acted more like an aristocrat. Art was honored by his willingness to practice it. The Amsterdam patricians, who were beginning to detach themselves from the people and assume a certain nobility, felt attracted to him more than to their fellow townsmen whom they considered either honorable family men of narrow development or as genius rakes or scatterbrains. In short: gentility, in the sense we use it nowadays, was on the rise, and Sandrart was a genteel man.

He also had a good introduction here [in Amsterdam], because he was a cousin and a good friend of his fellow townsman Michiel le Blon, with whom he had traveled through Italy. This art lover, connoisseur, and “agent” of Sweden was held in the highest esteem in Amsterdam, whether in the merchant world, or, without a doubt, in the best scientific and literary circles. His recommendation will certainly have caused a welcome reception in the city. Before long Sandrart received the honor of portraying the professors of the recently opened Atheneum.63 Vondel [sat for him] taken from the tragedies that he was just studying (as he himself wrote in his caption beneath his portrait).64 During the pleasant conversation with this civilized and traveled artist,65 the bailiff Hooft forgot the boredom that had tormented him when he sat for Mierevelt [fig. 14].66 Even Doctor Samuel Coster, who had recently been more occupied with his practice in the hospital [Binnengasthuis] than with the theater, was, on the occasion of his thirty years of service as the city physician, talked into having his portrait painted by Sandrart and donating it to the hospital.67 All these portraits were etched by Matham and Persijn, and most of them were published by Danckerts and provided with poetic captions by Barlaeus.

The portraits that were commissioned of Sandrart by the aristocracy are, because of the bequest of H. J. Bicker, nowadays present in the great portrait hall of the museum (nos. 1275–1278, formerly 524 a–d): the burgomaster Jacob Bicker and his brother Hendrik, with their wives, Alida Bicker and Eva Geelvinck [figs. 15–18]. Since these gentlemen Bicker were full cousins of Cornelis Bicker van Swieten, the captain in the civic guard portrait, it seems that the Bicker family were particularly charmed by Sandrart. We may therefore be twice as thankful to Roelof Bicker, the brother of Hendrik and Jacob that he, by choosing Van der Helst, remained loyal to Dutch art.68

That Sandrart had great merits is proven by his civic guard portrait, which is held to be one of his best pieces. Coloring and composition deserve praise and some of the portraits are excellent. To fulfill the assignment that the portrait should refer to the entrance of Marie de Medici, without making the queen the main protagonist, the painter conceived of the idea, not a bad one, to depict the civic guards as having come together to view a bust of the esteemed guest. That bust is placed in the middle of a low tripod table that is covered with a green carpet with a golden fringe. The bust is of white marble, the robe, draped over the shoulders of a dark yellow stone. The ugly, not very flattering portrait, with little that appears royal , and a low placement, give this main motive of the painting an unpleasant impression. One does not share the admiration that the civic guards show, especially those grouped on the right of the little table. Cornelis Bicker … forgive me — the Lord van Swieten (he bought this lordship eight years before) — is in a chair, holding a baton in his extended right hand in the pose of an emperor on his triumphal chariot. It was a nice decision by Sandrart that he does not let this magistrate aim his gaze at the bust. Between the figure of the captain and the table with the statue, the ensign can be seen, more to the back with a blue sash over the short yellow tunic, carrying an orange standard. To the left are a gray sergeant and ten civic guards, all clearly visible in an unforced manner. The background is not very evocative, but somewhat stiff and the architecture cold, while a drapery with cords finishes the unnatural and not very local surroundings.

On the little table, except for the bust, a golden lily crown is visible as well as a paper, hanging down, on which is written with elegant letters a poem that Vondel wrote for this painting “in an unguarded moment,” in the words of Huet.69 According to the spelling on the painting, it reads as follows:

THE COMPANY OF THE LORD VAN SWIETEN

Painted by Sandrart

Van Swieten’s standard waits, to welcome Medicis

But for such a great soul a square is too little

And the eyes of the burghers, too weak for such rays

That sun of the Christian world, is flesh, nor skin, nor bone

Then forgive Sandrart, that he painted her in stone.

HET CORPORAALSCHAP DES HEEREN VAN SWIETEN

Geschildert door Sandrart.

De vaan van SWIETEN wacht, om MEDICIS te onthaalen,

Maar voor zo groot een ziel is dan70 een Markt te kleen

En ’t oog der Burgerij, te zwak voor zulke straalen;

Die zon van ’t Christenrijk, is vleesch, nog vel, nog been,

Vergeef het dan SANDRART, dat hij haar maalt van steen.

Thanks to Vondel’s precaution, the burghers, without their damaging their eyes, were able to view the flesh- and boneless sun, for more than a century in the Arquebusier civic guard hall, then in the burgomaster’s room in the Town Hall, finally in the Chamber of Rarities in the City Archives, until it finally received a place of honor in the Rembrandt room in the new Rijksmuseum.

Sandrart did not remain in Amsterdam for long. When the Stockau estate, in the Pfalz-Neuburg, near Ingolstad was inherited by his wife, Johanna van Milkau, whom he had married in 1635, he sold his art collection, raising 16,000 guilders, and moved to Germany, for which departure Vondel wrote him farewell poems. He concentrated on improving the estate, which had suffered much from the war and was destroyed again in 1647 by the French. After peace was restored, a period of wealth and fame dawned for the Lord of Stockau. He decorated the churches and palaces of the South German sovereigns with his brush, works that were often praised by Vondel in verse. At the peace conference in Nuremberg everybody wanted to be portrayed by him. In the end, he produced up to two portraits in one day (!). His painting of the large peace banquet (1649), still present in the city hall of Nuremberg, was a Swedish gift to that city.

In the meantime, he moved to Augsburg. After his wife passed away in 1672, he moved to Nuremberg in 1674. From that town, he chose a second wife, the twenty-two-year-old Ester Blommart. He was already sixty-seven-years old, but received much pleasure from his marriage, because he did not die until 1688. Ester, who made a name for herself because of her strong memory and her love of collecting, lived until 1733. Sandrart never had children. But the son of his brother Jacob — whom he had invited to Amsterdam in those days and who was the pupil of Danckertsz for four years there and later with Hondius in Dantzig — and next to him his children Joan, Jacob, Susanna, and Joachim Jr., all engravers, held the family name in high esteem.

In his later years, he was occupied with writing, and he worked the theory and history of architecture, sculpture, and painting into a pair of lavishly illustrated folios that he entitled Teutsche Academie(Nuremberg, 1675).71 A national German spirit is not to be expected here, though. He only chose that title because it is to his compatriots that he is pointing out the examples of the ancients and the Italians. A new edition of this work was published by Dr. J. J. Volckmann in1768–73.