This article addresses the genesis and reception of three engravings representing peasants made by Albrecht Dürer between the years 1514 and 1519. These images have been interpreted as social commentary or low-brow farce; I argue their importance is art theoretical. In my view, they are the result of Dürer’s 1505–6 visit to Venice, where Italian artists derided his ability to work in a classical idiom. In response, I argue, Dürer developed a method of imitation that I call “inverse citation,” which veils a famous antique model in the guise of a boorish peasant. Following Luther’s rebellion against the Church, northern artists took up this technique with more polemical aims.

Dürer’s Peasant Pictures as a New Beginning

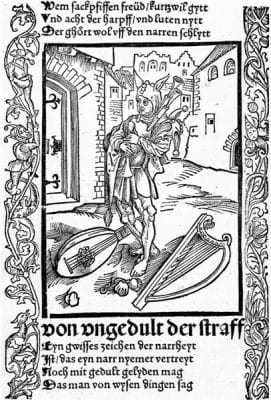

In 1514, Albrecht Dürer created two copperplate engravings that must be conceived as counterparts. One presents a bagpiper playing his pipe (fig. 1), while the other shows a peasant couple dancing (fig. 2). The corresponding subjects and similar compositions of the engravings, with the placement of the figures on a dark, narrow strip in the foreground, render them a pair. The background of both prints is blank, emphasizing the artist’s monogram and giving the figures a sculptural quality.

These are by no means the first engravings portraying peasants in the Nuremberg artist’s oeuvre, but never before have peasants appeared so monumental. This is achieved through intelligent compositional structure; because Dürer refrains from portraying the surroundings, the figures dominate the pictorial space. In comparison to his 1497 representation of rustic figures, which depicts three market-goers casually engaged in conversation, the poses of the figures in the 1514 engravings appear studied.1 The bagpiper, for instance, strikes up his tune with his limbs arranged in a rather deliberate configuration that gives him a melancholy air; he leans against a tree with his feet crossed and his head tilted in concentration.

Another striking aspect of the images is the artist’s meticulous observation of detail. The contour of the bagpiper’s smooth leather shoe clearly shows the toes of the right foot, a detail repeated in the foot of the dancer. The flowing lines of the creases in the woman’s apron seem to echo the direction of her spinning movement. The high-flying, wild hair of the male dancer, with his open mouth represented in profile, expresses unbounded merriment. Everything is depicted with the utmost precision and awareness of composition; in this scrupulous attention, we can perceive the ambition of the artist, who in the same year was to produce his most mysterious work, Melancolia I.

Art historians have interpreted these works in a number of ways. There has been the attempt by Marxist art historians to detect the artist’s sympathy for the peasant class in the engravings, an interpretation which can be justified to some extent by the monumental impression made by the figures.2 In Bauernsatiren, his comprehensive description of peasant images, Hans-Joachim Raupp undermines this reading, however, by convincingly outlining what he sees as a set of tropes characterize of the peasant genre.3 For the most part, Raupp’s discussion does not take into account the artistic ambitions of individual works like Dürer’s. Keith Moxey and Alison Stewart have also investigated peasant images as a genre in sixteenth-century German prints.4 Whereas Moxey sees the primary theme of such works as being mockery in the service of social differentiation (city-dwellers laughing at peasants), and Stewart argues that prints representing peasants partook in a humanist as well as a low-brow, humorous discourse, both scholars interpret the images in terms of their social context. My own approach stays close to Dürer’s images and reads them as an element of his larger art theoretical program. It is important to note that two peasant pictures were created at the same time as the Meisterstiche, the master engravings; this was a period of exploration in which Dürer used the medium of print to meditate on what art was capable of. As Erwin Panofsky makes clear in his studies on the artist, Dürer’s contact with Italian art and Italian art theory played a large role in these meditations.5 However, in contrast to Panofksy, I do not see Dürer’s relationship to Italian art as affirmative. In the following, I will argue that the two compositions were the result of Dürer’s second journey to Italy in the years 1505–6 and contain a critical comment on his experiences there.6

Dürer’s Rivalry with Italy

We have long been accustomed to citing Albrecht Dürer as the first northern European artist to devote his attention intensively to Italian and antique models.7 The journeys to Venice have been described many times, and their consequences neatly analysed.8 It is clear that the journeys to Italy brought a boost of innovation to the Nuremberg artist’s work, but the analysis of how he dealt with such influences has been far too indiscriminate, treating the artist as if he were a sort of vessel, empty at his arrival and full at his departure. We only have to read his letters of that period to perceive otherwise.

In a letter to his friend the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, from Venice, dated February 7, 1506, Dürer writes that he no longer likes those works that appealed to him during his first stay in Italy. More interestingly, for the first time he reports on the dislike his Italian colleagues felt for him; he feels well-nigh persecuted by them. In one passage, he accuses envious colleagues of theft: “I do have many enemies among them [i.e., the Italian painters] who copy my works in the churches or wherever they may get them; in order to criticise me afterwards and to claim that my work does not fully comply with classical art and therefore cannot please.”9

Some of Dürer’s Italian colleagues envied him because he had become a serious rival, evidence of his development since his first stay in Italy in 1495. Another letter to Pirckheimer, dated September 8, 1506, demonstrates that Dürer felt himself under pressure from his Italian critics. Triumphantly, he writes: “I also silenced all the painters who said that I was good at engraving, but in painting I didn’t know how to handle the colours. Now everyone says they have never before seen more beautiful colours.”10

Rivalry, as seen from the letters, does not have to be unconstructive. As Leonardo pointed out, one will envy artists who are more praised than oneself, but this can function as a positive goad to an artist to outstrip his competitors. Competition, in the sense of aemulatio, is one of the main driving forces of artistic progress.11 In my opinion, Dürer’s peasant pictures are his attempt to break the cycle of competition and rivalry that is described in his letters from Venice. Instead of a display of bravado, he responds with understatement – from the point of view of Italian artists, who valued antique models, there can hardly be a less spectacular topic than boorish peasants.

If we look closely, we can see that Dürer allows himself an ironic joke in his copperplate engravings. In examining the Bagpiper, we are struck at the peculiarity – anatomically speaking – of the foot set on the ground so that it allows a glimpse of the sole. The right leg seems strangely twisted. The skewed position of the head also appears awkward in view of the strenuous task of the bagpiper. However, we can understand the clumsiness of his posture if we detect the model the artist is alluding to. He cites no less a work than the piping Faun of Praxiteles (fig. 3), which has come down to us in various copies and variants. A sculpture by Antico from around 1500 (fig. 4) portraying the young Hercules reading shows how highly valued this particular image was and how much critical attention it received from contemporary artists.12 The Italian artist reproduces the static motif identically but replaces the pipe with a book.

Unlike his Italian predecessor, Dürer made a noticeable effort to hide the model, a fact that clearly shows his ironic intention.13 Praxiteles’s work is the very epitome of artistic grace, an equal to the Boy Extracting a Thorn. The motif of the crossed feet is particularly striking, but the boy’s elegant posture is also eye-catching. The faun is completely lost in his music. He seems to be making music and at the same time sent into raptures by his own music – a touching picture of self-forgetfulness. In Dürer’s boorish musician figure, this beauty is veiled by a kind of a Socratean mask. In the Symposium, Socrates is compared to a hollow statue of Silenus, which is ugly on the outside but contains beautiful, golden statues of the gods on the inside.14 Likewise, Dürer’s citation is only revealed to those who know how to look “inside” it.15

In light of the criticism that Dürer faced in Venice, his intention becomes clear. He chooses a typically German, i.e., inelegant, topic that invites the criticism of beholders versed in the Italo-antique tradition. Yet, the critic who assumes that the crudeness and simplicity of the subject equates to crude execution reveals his own ignorance. The way Dürer deliberately botches the detail of the elegantly crossed foot seems almost coquettish. This artist, after all, was the creator of the Adam and Eve (1504); he was certainly capable of portraying the ideal human form according to the antique canon. In the Bagpiper, the artist pulls back. It is as if Dürer gives us a glimpse of the peasant’s broken sole because he could not cope with the sight of so much gracefulness.

Inverse Citation

In his peasant engravings, Dürer invents nothing less than a new iconographic mode of art: the inverse citation. This mode aims first of all to unmask the “ideological” critics who esteem national considerations more highly than artistic ones. In doing so, he follows the advice of Quintilian in The Orator’s Education. The latter recommends the practice of dissimulatio in the sense of passive irony, according to which the speaker pretends to be ignorant but uses this feigned naïvete to tempt the opponent into feeling superior.16 This applies to the copperplate engraving in that the motif of the rustic musicians is negatively connoted. The contemporary viewer may have been reminded of the fifty-fourth chapter of Sebastian Brandt’s Ship of Fools (fig. 5), which presents the bagpiper as a symbol of foolishness and obstinacy. The instrument resembles the male sexual organ and signals man’s animal instincts, which seem to have become the bagpiper’s one and only concern. The lute and the harp, which lie on the ground, stand for the intellectual-spiritual dimension of music, as we are informed by the doggerel verses in the Ship of Fools: “Eyn sackpfiff ist des narren spil / Deer harppfen achtet er nit vil / Keyn gu(o)t dem narren in der welt / Baß dann syn kolb/, und pfiff gefelt.”17

The Peasant Dance has a similarly ironic pictorial structure. Dürer quite evidently concentrates on the boorish character of the dancers, who, although completely lacking in grace, are in very high spirits; the woman’s stocky build and the wild gestures are exploited as a source of comedy. A more critical examination reveals another level of wit. Dürer has included an optical irritation in his rendering: the peasants’ feet and calves are depicted in such a way that it is difficult at first sight to attribute each leg to its proper owner. The artist’s visual humour consists in creating the impression that the peasant woman has no right leg – according to the laws of physics, she should actually fall over. The artist intensifies this notion by staging the pictorial narrative along an ascending diagonal that starts with the foot of the peasant woman and continues toward her outstretched arm.

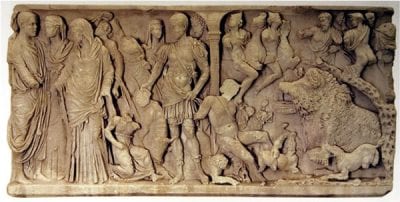

In this engraving, the cited work is nothing less than the Laocoön group (fig. 6), deployed once again with an ironic intention.18 The inversion of the model is comic and must be seen yet again in the context of an insinuated ignorance of antique culture. The peasant woman is literally and figuratively a mirror image of the statue. With her diagonally outstretched arms, bent legs and plump, womanly body, she both echoes and inverts the heroic figure of the priest of Poseidon. Note as well the male dancer with wildly flying locks who has opened his mouth wide to shout, reproducing another view of the famous sculpture. It is clear that Dürer studied the Laocoön group thoroughly, not only in order to paraphrase its form but also to reproduce it in a conventional way. This latter manner of quotation is demonstrated in his sketches for the Fugger Epitaph (fig. 7) from 1510, which similarly quotes the iconic, diagonally outstretched arms of the priest in the original.19 Recognizing in the form of the dancing peasant woman a distortion of the priest figure from the Laocoön group requires an eye that is as trained as it is erudite. Dürer exercises great skill in concealing his “citation,” while at the same time cleverly pointing to it. In the inverse citation, showing and concealing overlap.20

The more subtly an artist uses an allusion, the more he is required to give indirect hints that confirm the recipient in recognizing the citation – thus Dürer’s invention of the yelling dancer with his arm swung upwards, who reproduces another view of the central figure. A double movement is taking place in Dürer’s inverse-ironic citation. The cited subject is transformed beyond recognition and must therefore be evoked through the adoption of significant motifs like the shout and the open mouth, high-flying hair and the lifted arm – all centrally connected with the figure of the priest. But like any ironic statement that deserves the designation, it is easier to overlook than recognize. The difficulty of such a procedure is obvious: if the artist hides the model too much, the reference cannot be detected, and if the model is too easily recognized, the reference runs the risk of being perceived as a parody.

The fact, however, that Dürer developed this ironic mode of art following the confrontation with his Italian critics must not lead us to think that he did so only out of wounded vanity. On the contrary, a serious art-theoretical context needs to be considered here. Dürer’s peasant pictures mark the beginning of a new aesthetic potential in the visual arts – the potential for subversion. And as the Latin root of this word reminds us (sub means under), artistic standards and the degree to which they can be enforced are inseparable from each other. Culture has always been determined by questions of hegemony; in other words, the canon of antique works that includes the Laocoön owes its existence not to any objective criteria but rather to ability of the dominant civilization, that of Italy (or even of Rome), to impose its authority. Italian art theory followed the classical theory of types and – with regard to painting – is hierarchically structured. According to the hierarchy, the depiction of Christian or mythological historical subjects is the noblest task of the painter, who achieves a certain status with his choice of topic.21

Dürer made some critical remarks on this matter, writing in his theory of proportions: “But it must be noted that a gifted and trained artist is better able to show his genius and his skill by depicting a peasant figure and other simple motifs rather than executing important works of art.”22 As the passage makes clear, artistic quality is not bound to themes and motifs but follows purely aesthetic criteria. This must also be taken into consideration in Dürer’s choice of a small format and the less-valued print medium. For Dürer, medium could not, in and of itself, guarantee artistic pre-eminence.

Dürer, Vellert, Holbein

In July 1520, Dürer set out for the Low Countries, a journey thoroughly described for us in his travel diary. It is known for example that Dürer regularly met the Antwerp artist Dirck Vellert, whom he calls a glass painter and who in those years was dean of the Antwerp guild.23 He met the Fleming for the first time in the autumn of 1520, when the latter provided Dürer with red pigment derived from bricks. On May 12of the following year, Vellert arranged a banquet for Dürer, to which many artists and prominent persons were invited, as Dürer briefly reports – at least he mentions a delicious meal and that he was treated with “great honour.”24

Dürer produced his third copper engraving (fig. 8) dedicated to a peasant subject shortly before his journey to the Low Countries. The same size and format as the Dancing Peasants and the Bagpiper (all roughly 116 x 73 mm), the engraving of 1519 seems to have served on the journey as a gift for his hosts; he often mentions giving the “new peasant” as a gift.25 This time, however, the couple is not freestanding, but is positioned in front of a crumbling wall. The artist has painted the year between the heads of the couple and his monogram on a stone at their feet. The man, whose chubby cheeks and muscular build indicate that he is still young, stretches out his right arm; his purse is in his left hand, and he is about to say something. The meaning of the engraving is controversial, but it seems to me to allude to a sexual joke. The old woman holding two dead cocks in her left hand has made a sexual offer to the young man, who now anxiously holds his “money bag.” Further, the jug and the egg basket have sexual connotations. The subtext of Dürer’s picture is the theme of the unequal lovers; the brash old woman is juxtaposed in lewd contrast to a timid young man, who makes a gesture of rejection.26 A copper engraving with the monogram “bxg”, dated 1480, demonstrates that such an erotic level was not unexpected in the peasant genre (fig. 9). It shows an old woman opening her beau’s shirt while he touches her breast.27 This erotic behaviour is accompanied by a financial transaction, as the old woman hands over her purse to pay for the received caresses.28

Five years had passed between the first two peasant pictures and the making of Peasants at the Market, but it is apparent that the artist has endowed the third copper engraving with a cryptic ironic dimension as well. Dürer uses his technique of dissimulatio to analogize his peasant to a Roman soldier, for instance, those found on sarcophagi (fig. 10). Dürer evidently saw his peasant pictures as a series, all following the same ironic laws. The allusions made in these works are so tremendously complicated that they require the reciprocal interconnection of all three works of art.

Who was then able to understand such sophistication? Dürer’s anecdotes indicate that he was addressing his artist colleagues, but even without the art theoretical subtext, the copper engravings offer the beholder an aesthetically satisfying experience. The important point here is that solemn antique motifs are re-molded into humorous, genre-type scenes; gravity is concealed behind flippancy. Artists, particularly in the north, who had experienced the arrogance and condescension of their Italian colleagues as a thorn in their sides, must have appreciated such humour.

Unfortunately, we do not know the topic of conversation at the banquet arranged in Antwerp for Dürer by Dirk Vellert. Perhaps the Flemish artists asked him to talk about his journeys to Italy. Maybe they even asked him to tell them about the important works of art that he studied on the other side of the Alps. In any case, we can see how Dürer’s ironic treatment of ancient models was received by his northern colleagues in the works of Vellert, who was active in Antwerp from 1511 to 1544.29

Beginning in the early 1520s, immediately after Dürer’s arrival in Antwerp, Vellert began to produce ironic images of the Laocoön. It is impossible to say if Vellert learned the technique from Dürer during his stay in the southern Low Countries, or if he discovered the visual humour of the Nuremberg artist on his own. Whatever the case may have been, we can judge the effect of Dürer’s visit in two etchings by Vellert that take the Laocoön as their model. A portrayal of Bacchus (fig. 11) dates from 1522 and that of a bellowing drinker (fig. 12) from 1525. Once more, the etchings transpose the main motif of the antique sculptural group into a genre-type scene. The drunken Bacchus has to prop himself up so as not to lose his balance, while the drinker has already lost his composure. Intoxicated as he is, he calls out for more beer, his gaping mouth perverting the impression of noble suffering made by the open-mouthed priest. This image perverts the impression of noble suffering made by the open mouth of the priest into an image of vulgarity.

Like Dürer before him, Vellert engaged in serious study of the sculptural group. This is proven by an undated drawing (fig. 13) showing Bileam and the she-ass. To the right and left of the falling prophet, his arms extended in the iconic Laocoön diagonal, we recognize two servants, an allusion to Laocoön’s sons. The Antwerp artist demonstrates two things with his adaptations from antiquity. First, he manages to deploy the classical model within the context of the Bileam narrative while more or less upholding the iconographic meaning.30 The blinded ancient priest is changed into a (figuratively) blind prophet. Second, the artist reveals an ironic intention by turning the tragic (Laocoön’s demise) into the ridiculous (Bileam’s dispute with the donkey), filling an elevated form with comic content. Vellert’s treatment of the Laocoön demonstrates that the inverse citation is an artistic exercise. The ability to so invert a model was apparently seen as proof of consummate artistic skill.31 Hans Holbein allows himself a similar jest in the “Imagines mortis” graphic series, where he constantly paraphrases motifs from the Laocoön group.32

Such a subversion of the Laocoön would not have been possible if its role as an aesthetic norm had not already been established, as it was in the Italian High Renaissance, whose artists relied on antiquity as a source.33 Subversion as an artistic practice is parasitical in that it cannot exist without a host. For the works of antiquity to have achieved the status of an aesthetic norm they had to be accessible, which became increasingly true during the pontificate of Julius II, who assembled an extraordinary collection of ancient works of art, began the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica, and employed the two most prominent artists of the sixteenth century, Raphael and Michelangelo. Besides St. Peter’s, emblems of this grandiose art policy include the adornment of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo, Raphael’s stanze, and the rediscovery of the Laocoön group in 1506 and its incorporation into the papal collections.34 In fact, the Laocoön became a sort of papal trade mark; Julius II exploited the rediscovery of the Hellenistic figural group, using it to confirm his predestination as pope.35

All of this was too much for northern European theologians of the time. Already resentful of his martial church policy, they felt Julius II’s patronage was too pagan and ambitious for a pope. The pope’s self-fashioning as a successor of the Roman emperors can be perceived in his enthusiasm for classical antiquity in literature and the visual arts, which he deployed as discernibly imperial gestures.36 The polemical dialogue of Erasmus, Julius Excluded from Heaven is a good illustration of this context. The tract, which first appeared in 1515 in Leiden, offers a damning portrait of the head of the Catholic Church. In Julius’s conversation with Saint Peter, he reveals himself as an unchristian despot who cannot be helped and is therefore refused access to heaven.

Ulrich von Hutten was once thought to be the author of this papal satire, but stylistic comparisons add credence to the argument that Erasmus is its author. The tone of the dialogue is already evident at the beginning, when Peter is called to heaven’s gate. Peter thinks that the Renaissance pope who asks for admittance is Caesar and calls him the “wicked pagan Julius,” to which Julius replies “Ma di si!”37 When the apostle then refuses to open heaven’s gate, Julius threatens him with excommunication. One farce follows another. It is easy to understand why the text appealed to Luther; according to the testimony of Bonifacius Amerbach, it was still being closely read in 1528.38

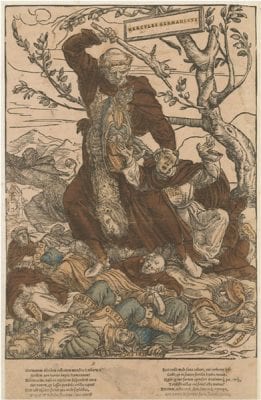

On a practical level, the papal claim for cultural hegemony coincided with the circulation of printed graphic versions of the aforementioned works of art. The fame of these masterpieces spread rapidly in the north, and they were no less rapidly taken up and adapted by artists. As mentioned above, by 1510 Dürer had already used the central motif of the Laocoön group for his sketches of the Fugger Epitaph, four years after the rediscovery of the antique sculpture. In 1522, Hans Holbein made polemical use of this model for his portrayal of Luther as “Hercules germanicus” (fig. 14).39 Luther kills the Catholic Hydra while the pygmy-like pope is hanging on his nose.40

Inverse Citations in the Art of the Reformation

For Dürer, the issue was restricted to an artistic competition with Italy, but for following generations of northern European artists this conflict was exacerbated by the Reformation.41 From the early 1520s onward, what mattered was the emancipation of German art, the fight for equality with ancient and Italian models. In the year 1520, Luther published To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation Concerning the Reform of the Christian Estate. With this text he makes a definitive break with the Catholic Church by identifying the pope with the Antichrist. After having criticized letters of indulgence, bulls, confessional letters, “butter-letters,” and other confessionalia, Luther wrote the following passage in his treatise: “I shall also say nothing at present of how this indulgence money has been applied. Another time I shall inquire about that, for Campoflore and Belvedere and certain other places are very much aware of it.”42 The mention of the Cortile del Belvedere is a metonymic allusion to the sculptures erected there. The message is clear: the money of the German Christian finances the expensive art collecting and building policies of the pope. The fact that the Laocoön was politically exploited in order to show the cultural superiority of the papacy did not escape attention in the north und provoked strong objection.43 Seen from a reformist point of view, the Laocoön was a Catholic showpiece that virtually asked for mockery.

Finally, I wish to underline the modernity of the sixteenth century, which is revealed in the potential of nonequivalent aesthetics.44 Beginning with pagan antiquity, the aesthetic experience is understood to be based on a harmony between inside and outside. Outer beauty and inner virtue refer to each other. But this changes within the framework of Christian-reformist poetics. When inside and the outside diverge, when their relation is perceived as a conflict, nonequivalence determines the aesthetic experience. In such an aesthetics, the visible is in a way denounced, the actual step of perception leads beyond the visible and must be performed mentally. It is the special achievement of ironic art to allow form and content to diverge. Form is not imagined as a vessel of a fixed content, but the reversal that occurs with its recognition sets free a particular semantic potential.