The history of research on the Miraflores Altarpiece is a most peculiar one. For more than a century, it was judged to be a copy after Rogier van der Weyden, while a second version, the Granada–New York Altarpiece, was regarded as the original. Both connoisseurship and technical investigation seemed to corroborate this until the contrary was proved in 1981. In the history of technical research on the altarpiece, Johannes Taubert played an instructive role, particularly concerning the relationship of connoisseurship to technical research and the conclusions drawn from it. This article examines that role and offers some thoughts about its implications for future research.

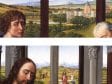

The tripartite panel painting that is today known as the Miraflores Altarpiece (fig. 1), one of the highlights of the Berlin Gemäldegalerie, was introduced into art history as a work by Hans Memling by Gustav Friedrich Waagen in 1838.1 Yet just five years later, Chrétien Jean Nieuwenhuys was able to attribute it to Rogier van der Weyden on the strength of the entry in a chronicle of the Charterhouse of Miraflores in Spain, where the work had been kept until the early nineteenth century.2 This well-known entry gives a short description of the scenes and mentions that the work was painted by “Magistro Rogel, magno et famoso flandresco.”3

In the same year, 1843, Johann David Passavant described the Miraflores Altarpiece and praised it as an exquisite work of Rogier van der Weyden, surpassing in its nobility and expression the majority of early Netherlandish paintings.4 Ten years later, however, Passavant had changed his mind, by then considering the very same work to be an old copy from the beginning of the sixteenth century, a judgment based on the supposedly “stiff” outlines and the manner in which the landscape is painted.5 Thus we might say that Passavant’s comment of 1853 marked the birth of the extremely successful and long-lived opinion that the Miraflores Altarpiece is a slightly inferior copy of an original by Rogier van der Weyden. This assessment is all the more astonishing as the twin of the Miraflores Altarpiece, the so-called Granada–New York Altarpiece (fig. 2), was completely unknown at the time. This latter work, or, rather, its Granada portion, was only published in 1908 by Manuel Gómez-Moreno, who declared it to be the original by Rogier van der Weyden, and the Berlin panels to be copies of it.6 This view was to be shared by scholars almost unanimously for the next 70 seventy years, including leading figures in the field such as Max J. Friedländer, Friedrich Winkler, Erwin Panofsky, Martin Davies, and many others.

In the mid-1950s, the restorer Johannes Taubert turned to the Granada–New York and Miraflores altarpieces in the context of his pioneering PhD dissertation on the use of technical investigations for art history.7 His starting point seems to have been Erwin Panofsky’s remark on the two works in his magnum opus Early Netherlandish Painting, for Taubert quotes the three possible explanations that Panofsky offers for the existence of the twin altarpieces: Either both paintings were made in Rogier’s workshop, or the Granada–New York Altarpiece is a later copy, or the Miraflores Altarpiece is a later copy. Panofsky strictly excluded the idea that the Granada–New York version was the copy; instead he preferred the first alternative with the proviso “that the Berlin triptych is the second rather than the first edition” (fig. 3).8

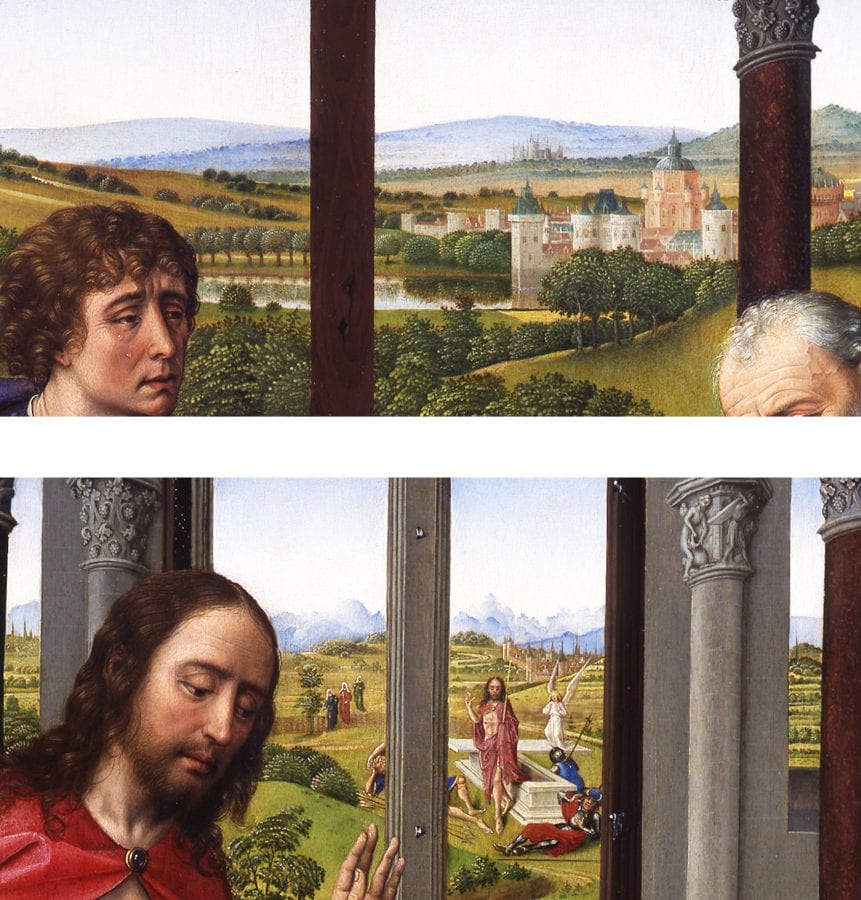

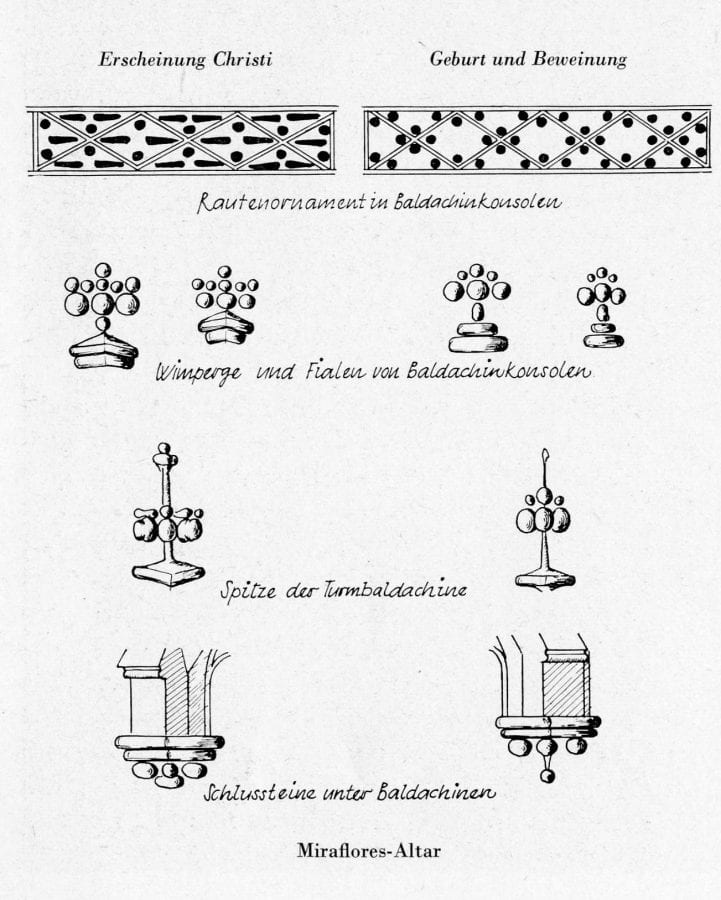

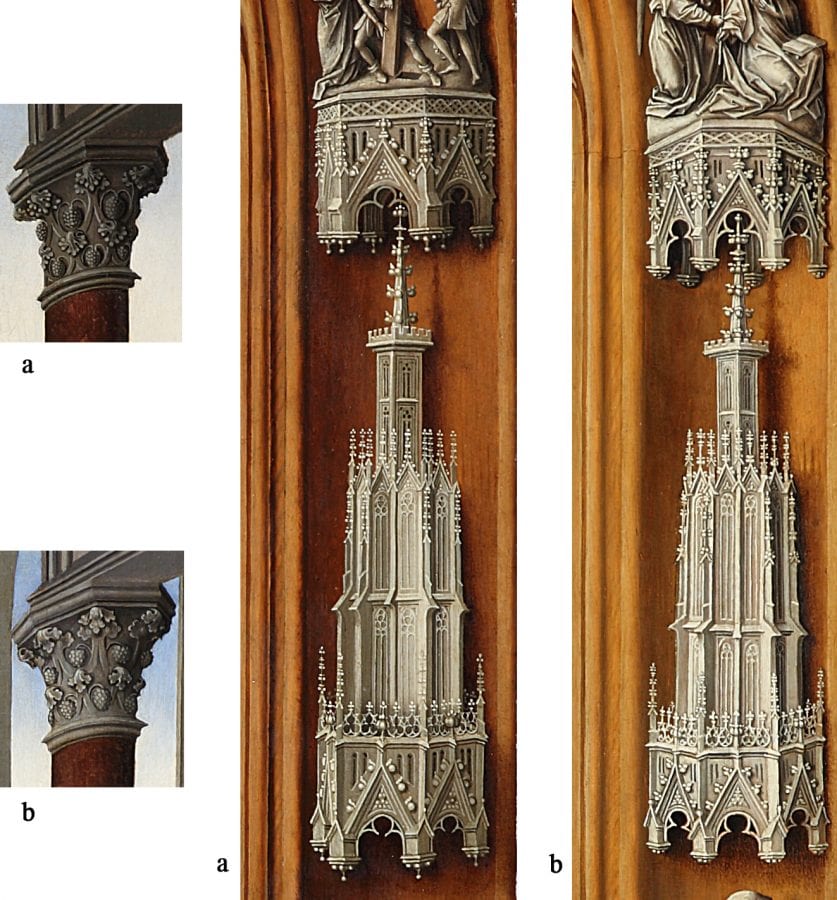

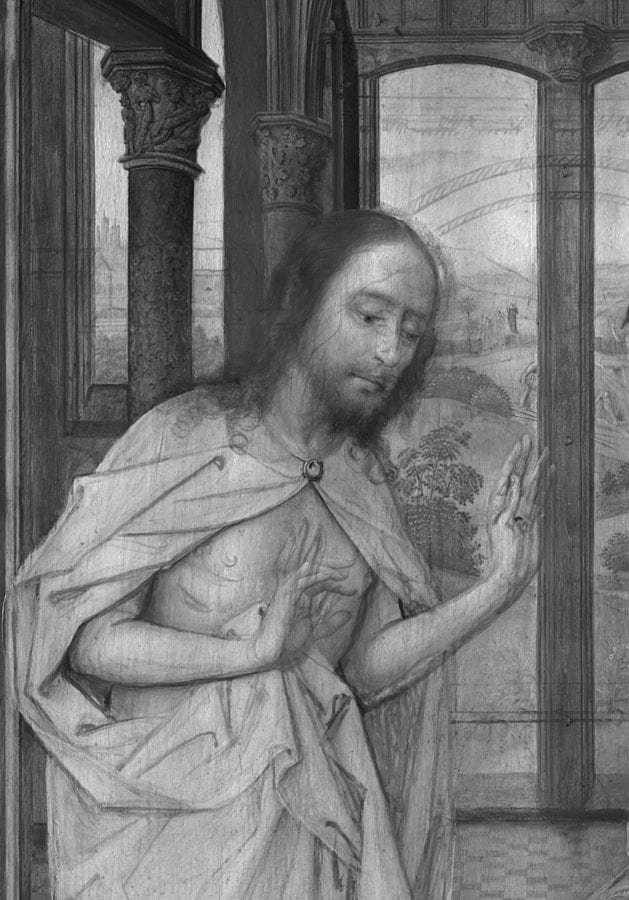

Taubert mostly worked on the Berlin altarpiece, using the microscope and photographic macro-images—new technical devices in the study of early Netherlandish painting at the time. What he found are very small but consistent differences between the right panel and the rest of the work: capitals, canopies, minute architectural ornaments, and the landscape differ in Christ Appearing to His Mother from the other two panels. For instance, the canopies and capitals are shown frontally in the former, whereas in the other two panels they are foreshortened; details like the grapes on the capitals are different in the Christ Appearing to His Mother and the Lamentation. Taubert visualized his observations in a schematic drawing of some small details of the architecture (fig. 4). Thus, in the end his “technical” approach was nothing other than a variant of the good old Morellian method, that is, to describe and compare details in two or more paintings in order to distinguish different hands. The new aspect, however, was the application of this method to very small details with the help of magnifying optical devices.

All of Taubert’s observations on the individual panels of the Miraflores Altarpiece are indeed accurate and can be successfully checked by reference to the original (fig. 5). However, his conclusions are rather astonishing: in a way, he split the work, attributing only the right panel, Christ Appearing to His Mother, to Rogier himself, while the other two were judged to be copies executed in the second half of the fifteenth century in Spain. In the other triptych, the Granada–New York Altarpiece, Taubert recognized a later copy, a copy that was already based—in his opinion—on the heterogeneous Miraflores Altarpiece and was characterized by the thin pastel-colored paint typical for the time around 1500.9 With this latter observation, he was, no doubt, right.

But why did Taubert come to his conclusions about the Berlin work, conclusions that eventually resulted in the positing of three, instead of only two, versions of the Miraflores-compositions? Undoubtedly, it was because he had accepted the prevailing scholarly opinion that something must be wrong with the Berlin altarpiece. This was such a firm belief that he could not accept the whole of the Miraflores Altarpiece as the original, despite the fact that he himself had recognized the other version as a later copy.

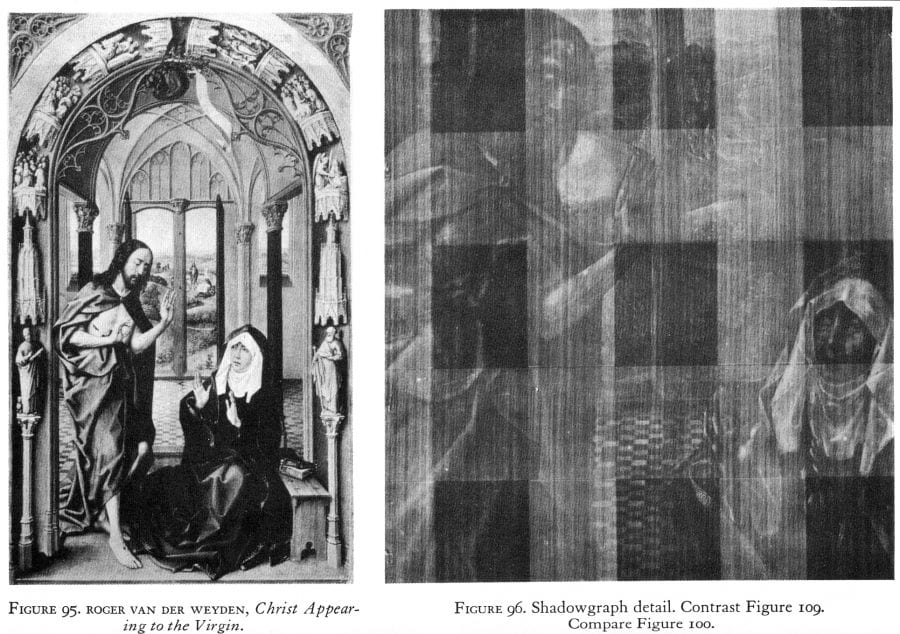

More or less the same basic assumptions as Taubert’s can be observed in other early technical investigations of the paintings in question. When Alan Burroughs conducted x-radiography of a number of paintings attributed to Rogier van der Weyden in the late 1930s, he claimed this to be a new and objective means for attribution, one based on the comparison of different painting techniques as revealed in the radiographs. What he detected in the New York panel of Christ Appearing to His Mother (fig. 6) was the typical brushwork of Rogier.10 Likewise, Roger van Schoute, in the Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas volume of 1963, found the painterly execution of the Granada panels to speak in favor of Rogier’s authorship.11 Using infrared photos, he also recognized some small alterations in the underdrawing of those panels and judged them to be a further proof of the originality of the work.

Yet Van Schoute’s technical means with respect to underdrawing were limited, and there was no such material on the Berlin panels available at the time. Indeed, it was technical progress that finally solved the riddle of the two altarpieces. Infrared reflectography, even in its early stages, provided much better images of the underdrawing, and with its help, Rainald Grosshans in 1981 was able to reveal substantial changes in the panels of the Miraflores Altarpiece, especially in the Christ Appearing to His Mother, where the background was at first planned as a closed interior and only later changed into the landscape we see today (fig. 7).12 Thus it became clear that the Berlin version was the model whose ultimate state of execution was copied in the Granada–New York version. Dendrochronology provided final proof, showing that the Miraflores Altarpiece could have been painted as early as the 1430s, whereas the other version could not have been begun before the very end of the fifteenth century.13

Images generated by IRR were the decisive means for a new appraisal of the Miraflores Altarpiece, and the substantial changes that were thus made visible convinced more or less every scholar of the originality of the Berlin work. However, sometimes we are far away from distinguishing between original and copy just by finding pentimenti. This becomes clear in the case of the Portrait of Pope Julius II, acquired a couple of years ago by the Städel Museum.14 Another version of the pope’s likeness in London is generally believed to be the original by Raphael. The x-rays of both versions, in London and in Frankfurt, reveal changes in each: while the background of the Julius in London has been changed, in the Frankfurt piece the chair has been altered in the course of execution and its final form resembles that of the chair in London. This at first led to the consideration that the Frankfurt version might be the original, a possibility that was quickly abandoned, however.15 The London panel was and still is considered to be of higher artistic quality, showing all the hallmarks of Raphael’s authentic works. Yet it is not easy to explain why the London version adopted the position of the chair from the Frankfurt panel. Could one of these two be a creative copy that imitates the style of Raphael? Even Giulio Romano, pupil of Raphael, had been misled by a painting by Andrea del Sarto, which copied Raphael’s Portrait of Pope Leo X in the master’s style. When Giulio Romano was told that he was looking at a copy, he just answered: “I don’t consider it less than if it were by the hand of Raphael, because it is outstanding that a man is able to imitate another painter’s style that faithfully.”16

Today, we are probably less generous than Giulio Romano; we want to know whether a painting is by a certain master’s hand or not, and we judge its quality accordingly. Technical investigations of early Netherlandish paintings are intrinsically tied to these two aspects of attribution and quality. Different technical approaches were developed in the first place for attribution purposes, and often they are not independent of more or less preconceived opinions on quality, as we have seen in the case of the Miraflores Altarpiece.

The importance of these two aspects can be felt in most of the major technical studies on early Netherlandish painting, for example in the groundbreaking work in the field, the comprehensive investigation of underdrawings in the Rogier van der Weyden and Master of Flémalle groups, published by J. R. J van Asperen de Boer and his team in 1992.17 Their study claims to arrange the Rogerian works primarily on the basis of the style of underdrawing, and thus some works are clustered in a “core group” while others, for example the Abegg Triptych (Riggisberg, Switzerland, Abegg Foundation) are placed in a remote position. With respect to the latter, the team thus confirms an opinion that has prevailed since Panofsky, who saw the Abegg Triptych as a pastiche after Rogier.18

In the case of another work, the Columba Altarpiece (Munich, Alte Pinakothek), unanimously attributed to Rogier, the situation looks very different. Here, underdrawings are revealed that, according to the authors, are “totally at variance with what is observed in the core group [of Rogier van der Weyden], but are also not encountered anywhere else in the group.”19 However, the Columba Altarpiece is not removed from Rogier’s oeuvre in this study because its design and painterly execution are judged to be of such a high quality that the work must be by the master’s own hand. As an explanation, the researchers assumed that Rogier himself did both the design and most of the painterly execution but had his preparatory drawings transferred to the panels by an assistant. To be sure, this hypothesis could be correct. Nevertheless, it seems that a substantial problem of logic arises here: if works are attributed to a master according to their underdrawing style, but a certain work with an atypical underdrawing is kept in the core group with the help of an explanation like the one just cited, every reason to reject others is lost, for what is true for the Columba Altarpiece might well be true for every other painting with an underdrawing atypical for Rogier.

In both the instances of the Abegg and the Columba triptychs, the conclusions drawn from technical investigations confirmed the predominant assessments of the works at the time. And the same is true, as we have seen, for the judgments on the Granada–New York and Miraflores altarpieces prior to 1981. Even though these conclusions might be right in the first two examples, but are definitely wrong in the latter one, it seems that in the end all of them indeed depend on opinions that have been established by traditional stylistic approaches to the visible surface of the paintings in question. The Dutch research team’s reasoning about the status of the Columba Altarpiece implicitly acknowledges the predominance of old-school connoisseurship with the naked eye. This observation might be a bit at odds with the prestige that technical investigations, and especially IRR, are enjoying, at least on a rhetorical level.

All the approaches mentioned so far—the study of underdrawing, the conducting of x-radiography, and of course Taubert’s Morellian use of a magnifying glass—are working with images, no matter whether they are generated by technical means or not. If we use images to discuss attributions, we inevitably have to apply judgments of style—the team around Van Asperen de Boer was well aware of this in their study just cited, and they accordingly placed their stylistic interpretations of underdrawings under the headline “author’s personal opinion.” Technical investigations are not a substitute or a more objective replacement for connoisseurship; on the contrary, their interpretation is nothing but connoisseurship of images that are not visible to the naked eye, and ongoing technical developments will probably not change this situation. Yet there is no reason to lament the situation. Continuing attempts at attribution, even if it has been done many times before, are indispensable for understanding works of art. Understanding always has to be renewed, and thus attributions have to be renewed too.

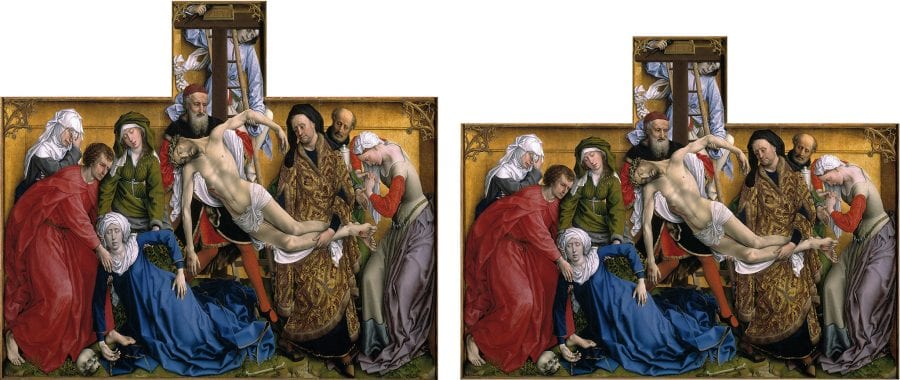

As everybody knows, stylistic judgments are more or less subjective. Nevertheless, to a certain degree they are also objective. For example, everybody with a sound knowledge of early Netherlandish painting will distinguish a work from around 1400 from one that was made thirty years later. The challenge starts when it comes to more sophisticated aspects of attribution, such as distinguishing an individual hand among a group of closely related paintings. Neither IRR nor XRF scans will solve such questions without stylistic judgment. And if it comes to other methods of investigation that do not create images, like dendrochronology or the analysis of pigments and binding media, their relevance with respect to attribution is probably very limited. If we may exaggerate a little, the interpretation of the results of such methods seems not less, but more subjective than straightforward stylistic judgments—we may think of the sometimes rather arbitrary interpretations of dendrochronological findings, which have no difficultly in assuming singular exceptions from the statistics for the sake of a date assumed a priori. A somewhat funny case demonstrates that long-standing assumptions can have priority even over real hard facts: the measurements of one of the most famous of all early Netherlandish paintings, Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross in the Prado Museum, are invariably given as ca. 220 x 262 cm, from Friedländer’s corpus volume of 1924 to the post-war Prado catalogues to all subsequent monographs on Rogier, such as those by Martin Davies and by Dirk de Vos, until the most recent exhibition catalogue.20 Yet a panel of those dimensions has different proportions than the one in the Prado (fig. 8), the actual size of which is 204.5 x 261.5 cm, more than 15 cm shorter in the vertical axis than usually indicated.21 The repeated repetition of (incorrect) measurements was obviously so commanding that for nearly a century neither an estimation of the panel’s proportions nor the application of a ruler was even considered.

Looking back at Taubert’s work on the Miraflores Altarpiece from sixty years ago, we can wonder about his conclusions regarding the authorship of the individual panels. Knowing what came to light in 1981, his admittedly original idea seems as strange to us as do other earlier appraisals of the twin altarpieces; the same idea applies to Max Friedländer’s judgment that the Christ Appearing to His Mother from the Miraflores Altarpiece proved to be inferior to the version today in New York when the two were placed next to each other in 1920 in Berlin (see fig. 3) and likewise to Burroughs’ or Van Schoute’s recognition of Rogier’s hand in the painting technique of the Granada–New York panels.

The riddle of the twin altarpieces has been solved with the help of advanced technical applications. Yet the Miraflores Altarpiece has gained its present status as an unquestionable original by Rogier van der Weyden not by an actual attribution, i.e., not on the basis of an assessment of personal style, of handwriting, or brushwork. It was the revelation of substantial changes made in the creation process plus dendrochronology. In terms of stylistic approaches, the history of the attribution of the twin altarpieces has indeed proved to be a spectacular failure of traditional connoisseurship, as someone has put it aptly—but it is a no less spectacular failure of attribution with the help of technical means.

Technical means have much evolved since Grosshans’s article of 1981, and of course we have made new digital IRRs of the panels of the Miraflores Altarpiece—especially as we are presently working on a scholarly catalogue of the fifteenth-century Netherlandish and French paintings at the Gemäldegalerie Berlin. It is not surprising that our new IRRs confirm the findings made more than thirty-five years ago (fig. 9). The images are clearer now, and they show some more details but in the end, this only adds up to a longer list of changes in the creation process of the work, not to fundamentally new insights. Thus, we cannot offer spectacular findings in our new infrared reflectograms or x-radiographs. Nevertheless, the results of the technical campaign of around 1980 can lead us to a different understanding of Taubert’s still-correct observations about the small differences between the right panel and the remainder of the work. Taubert was so deeply captured by the assumption that the Miraflores Altarpiece cannot be an uncompromised work by Rogier that an alternative and much less far-fetched explanation did not come into his mind: that the Miraflores Altarpiece is a genuine work by Rogier that was painted with the help of studio assistants. In our eyes, this is in the first place suggested by the landscapes on the middle and on the right panel, which are indeed very different in drawing and color scheme (fig. 10). However, it seems that it is not easy for the scholarly world to accept workshop collaboration in an important, even crucial work, which the Miraflores Altarpiece has become for the Rogier group. In former times, it was impossible to imagine that Rogier himself created this work. Today, after the fundamental change in the estimation of it that was brought about by advanced technologies, it seems unthinkable that anybody else but the master had touched it.