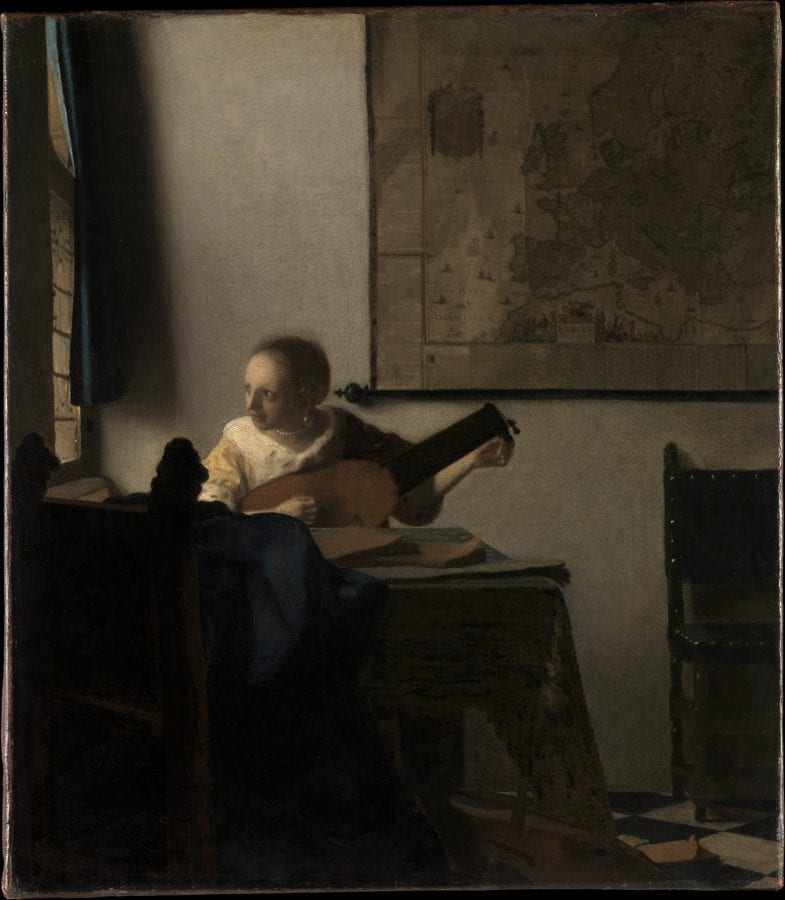

This essay explores Vermeer’s painting known as A Woman with a Lute from the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a visual poem on amorous and artistic longing. A closer look at its key elements—from the musical instrument being tuned by the lady to the map on the wall behind her—shows that this seemingly unmediated view into a private world is as engaged with ideas as Vermeer’s more overtly allegorical compositions. Most notable among these ideas are the relationship between the microcosm and the macrocosm, the notion that every record of the present is a form of “history,” and that the art of painting is no less eloquent in its silence than its sister arts of music or poetry. Ultimately, as in many other images of solitary females, with A Woman with a Lute the artist pulls us into a circle of desire, effectively turning us from beholders to coparticipants in a “composition,” whereby the absent comes back into presence.

There is something in art that can really make me happy: that part that lays its hand on the treadmill of time and that puts my grandfather’s grandfather in front of my eyes, as though he were a person from today or yesterday.

This art will pass on my face, which will die and decay with me, to the children of my children’s children. Is not art more masterful than time itself? It is a counterfeit in oil of what has to decay.1

When Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687) wrote these lines in 1656, he was echoing a long-standing discourse on the power of portraiture to transcend the boundaries of time. Furthermore, like earlier theorists, including Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), he was evoking a topos immortalized in an ancient story about the birth of painting from the outline drawn by a young woman around the shadow of her departing lover.2

Though we may never know if Vermeer read Huygens, no one who has ever looked at his paintings can deny his singular fascination with temporality. That fascination is the subject of this essay, which focuses on A Woman with a Lute from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig.1), a work that exemplifies the artist’s inimitable capacity to create small worlds which feel both exquisitely inviting and taciturn in their refinement. Through this seemingly contradictory message to his beholders, Vermeer secures his presence as a mediator of their experience—similarly to those dead writers and painters that Huygens considers among his most cherished friends: “Those [who are to blame for keeping me awake] are dead people . . . They are artists whom I don’t need to excuse. I command them to speak to me and they explain what is essential to their knowledge.”3

Any approach to that “essential knowledge” in A Woman with a Lute depends on close looking at what Vermeer chose to include, and what he left out of this painting. As always, there is very little to go on aside from visual evidence. Yet as I hope to demonstrate, this seductively real interior is as finely calibrated a construct as many of his allegories: A Woman with a Lute is not merely a view into an intimate moment but a visual poem thoroughly in line with Petrarchan conventions about love melancholy and self-consciously concerned with the act of composing—or the art of painting.4

To begin, one needs to go to the very center of this poem—the elegant lady tuning her lute for a musical performance. The scene’s air of seclusion is enhanced by the soft, cool light of a single window, as well as by the large table that shelters her from our gaze. The sparse furnishings of her room direct our attention toward the map of Europe behind her, which reinforces the contrast between her private space and the limitless world beyond.

Gazing absentmindedly toward that other world, our musician seems oblivious to everything except her delicate task—to bring her lute into perfect tune. Present yet unapproachable, she calls to mind Renaissance poems about ladies who desire to play their music in solitude so as not to betray the depth of their passions.5 Yet the longer we look, the more we feel that this moment is intended to be shared with someone: someone who will take pleasure in her beautiful form, someone without whom she cannot or will not begin to play. As Walter Liedtke noted with his characteristic astuteness and appreciation for irony, while Vermeer may be using this “tuning” to allude to the theme of temperance, he has also fashioned a “modern Venus in search of an Adonis or Mars.”6

That Mars or Adonis is the bewitched beholder, who is now taking the place of the painter who left this image as a testimony of her power. This circle of desire is familiar from Vermeer’s many images of music making and their Petrarchan conceits about a lady and her “supplicant.”7 Here it feels especially strong, given our proximity to her room, a closeness that only a lover or a painter can imagine sharing with his muse.

An empty chair leaning against the back wall creates a subtle message, as if to reproach us for our reluctance to come in. At the same time, a second one, placed at the very threshold of this image and half-obscured by a dark, billowing fabric—possibly a man’s cloak—hints that we are not the person she is expecting. This suggestion of absence is heightened by another vaguely visible element: a viola da gamba lying idly under the table. This instrument is also a familiar motif in Vermeer’s paintings on the subject of music—or rather, his Petrarchan inventions about the search for musical and amorous harmony.8 Both the lute and the viola da gamba were often used as metonyms for the human body in early modern literature.9 Thus, the French poetess Louise Labé (ca. 1520s–1566) would address her lute as a fellow sufferer in love who could give voice to her feelings. In her Sonnet XII, she calls this instrument her “companion in adversity” and “moderator” of her emotional turmoil, caused by the absence of her lover.10 In a similar vein, the English poet Thomas Campion (1567–1620) would speak of his beloved’s music making as the source of sympathetic responses within his soul.11

Labé’s plaintive verse also relates to the idea that to play the lute only for oneself is against its nature as a symbol of harmony and perfect unison.12 Love songs by composers such as John Dowland (1563–1626), who enjoyed great popularity in seventeenth-century Holland, were generally intended to be played in duets with lute and viola da gamba, the female and male instrument par excellence.13

This gendering of musical instruments could also be quite fluid. Shakespeare (1564–1616) likens a female character in one of his plays to a “fair viol,” whose senses are the “strings” that create heavenly joy in the man who can “finger” them as he makes his “lawful music.”14 In the same time period, in a poem titled The Lady and her Viol attributed to John Donne (1572–1631), the poet/lover pines for his beloved while she lavishes her attention on her lute as his alter ego:

Thou’lt kindly set him on thy lap, embrace

And almost kiss, while I must void the place.

Thou’lt string him truly, tune him sweetly, when

Thou’t wrest me out of tune and crack me then. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dear, as the instrument would I were thine,

That thou mightst play on me or thou wert mine.15

In Woman with a Lute, that dejected poet/lover is the beholder who enjoys privileged access to a private moment while remaining forever outside. This tension between visual possession and the elusiveness of our object of desire is a source of aesthetic pleasure throughout Vermeer’s oeuvre. Consider, for instance, A Lady Writing (ca. 1665–66), another of his portraits of a young woman engaged in a “composition” (fig. 2). Instead of playing music, she is appealing to her absent paramour through her letter. This idea is reinforced by the painting behind her, which depicts an assortment of musical instruments, as if to remind us that the words of the beloved are music for the lover’s ears.

While this letter writer is also readying herself for her “performance,” unlike the lute player, she acknowledges our presence. At the same time, her writing creates a suggestive parallel to the painter’s paean to her beauty, recalling that other Petrarchan standby which identifies painting and poetry as the body and the soul of the beloved, respectively.16 Though her lover may be someone other than us, that distinction is collapsed through the meeting of our gazes, an encounter that makes us a “captive” awaiting a token of her affection—the words we will never receive.

The intimation of her “voice” is just as tantalizing as the tune we await gazing at the lute player. Moreover, in both of these compositions, that admiring gaze inevitably takes us back to the painter, whose own desire led to the works we behold (and desire in turn). In A Lady Writing, this conflation between the painter and the beholder centers on the analogy between the pen with which she inscribes her words and the brush he used to create her counterfeit presence.17 In A Woman with a Lute, this conflation is enacted by the musical instruments—the one that is being tuned and the other that awaits a second player: the absent companion, the painter, and the beholder.

This meditation on amorous and artistic desire is amplified by the map. Though Vermeer is known for his fondness for cartographic motifs, his maps and globes are never merely compositional devices. Like the musical instruments and the chairs, they are invariably repositories of metaphoric meanings.18

In A Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (fig. 3), the map performs a similar function to that in A Woman with a Lute—to draw our attention to someone’s absence. In The Art of Painting or the pendant pieces known as The Geographer and The Astronomer , the cartographic motifs exemplify Vermeer’s erudition and artistic ambition. And in A Woman with a Pearl Necklace (Berlin), the artist painted a map, and then covered it up, as if to lessen the association between his sitter and the common female personification of worldliness, typically known as Vrouw Wereld (Lady World).19

For all of the specificity of Vermeer’s maps and globes, his attention to detail can sometimes have a counter-effect—it heightens their subtly allegorical quality. The map on the wall in The Art of Painting feels so real that one can almost imagine touching its slightly weathered, creased surface. And yet, as one tries to reconcile the designation of this map as a “new description” with the fact that it shows the political reality of a century earlier, when the seventeen Netherlandish provinces were still united, one becomes only more aware that every other visual “fact” in this artist’s studio may be a carefully crafted fiction.20

The map in A Woman with a Lute operates in the similar boundary zone between the real and the metaphorical. Unlike most of Vermeer’s maps, which show portions of the Low Countries, this one represents all of Europe. While this difference may not appear crucial, it helps bring into greater focus the age-old analogy between the microcosm and the macrocosm, central to so many of his pictorial conceits.21

Maps and mapmaking were commonly used as metaphors among poets like Donne, translated into Dutch by Huygens by about 1630 and praised for the “wealth of his unequalled wit.”22 One of Donne’s best-known invocations of maps as metaphors for the microcosm and the macrocosm occurs in his meditation on mortality known as the Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness. In the first stanza, he compares his preparation for death to a tuning of his body for God’s divine melody, evoking the Boethian distinction between heavenly music (musica mundana) and the music of the body (musica humana). In the second one, he envisions his doctors as cosmographers who will lovingly draw his features and interpret their signs—as if they were studying a map.

Even more famous is Donne’s comparison of himself to a “little world made cunningly,” which reflects a line of thinking going back to antiquity, with all of the attendant analogies between our blood and rivers, or our passions and sea storms.23 His analogy between the mapping of the world and the study of the human body also finds a correlative in anatomical treatises of the period, including one by Andreas Vesalius, who often depicts skeletons and flayed bodies against landscape backgrounds—as if to suggest that just as a land becomes knowable through a painting or a map so does the interior of the body through anatomy.24

The related parallel between maps and image making is no less important. Already in antiquity, Ptolemy compared mapmakers to chorographers (draftsmen), with the former focusing on the world (the body of the earth) and the latter on its parts (the human body).25 Vermeer’s fascination with maps cannot be seen outside this context, especially in view of Ptolemy’s placement of geography and mapmaking among “the loftiest and loveliest of intellectual pursuits” which “exhibit to human understanding through mathematics both the heavens themselves in their physical nature . . . and the nature of the earth through a portrait since the real earth, being enormous and not surrounding us, cannot be inspected by any one person either as a whole or part by part.”26

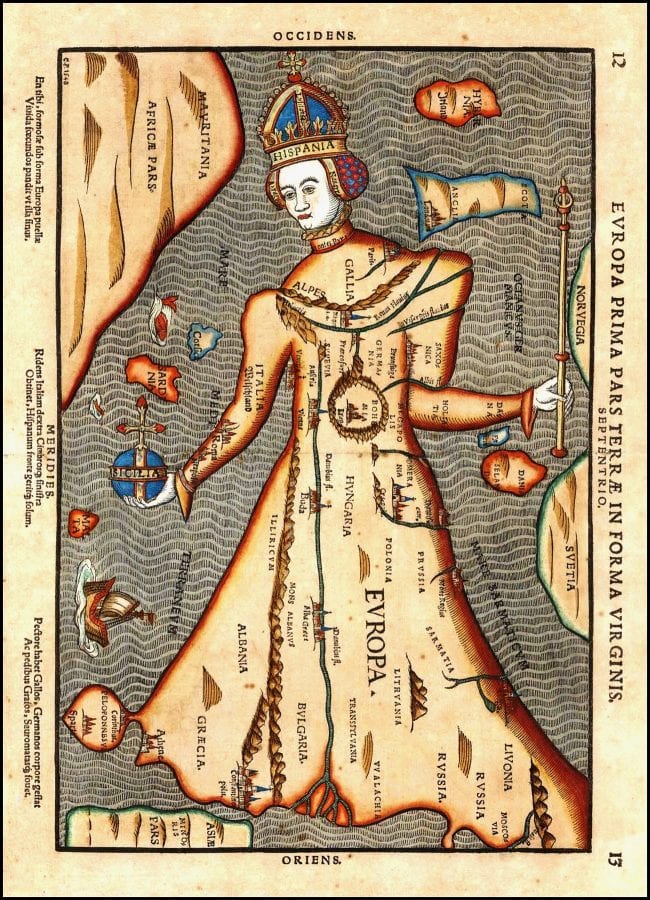

Ptolemy’s ideas continued to live in the anthropomorphic maps of the Renaissance, such as “Queen” Europe in Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia (fig. 4).27 Similarly, Mercator and Ortelius continued to use personifications of continents, with Europe and Asia often shown as elegantly dressed ladies, while Africa and America appear as nude virgins, as if to allude to “unpossessed sites of colonial desire.”28 In view of this anthropomorphic cartography, the proximity between the female figure and the map in A Woman with a Lute can also be seen as an emblem for the relationship between the “little world” of the lady and the all-encompassing world she exists within.

This is similar to Donne’s poetic concetti, where even the smallest of interiors, when occupied by him and his beloved, becomes a self-sufficient empire. In one of his poems, he compares his beloved to a treasure greater than all the riches of India—she is a universe of “all states” governed by a single prince (himself) for whom “nothing else is.”29 In another one, she is his newfound America, a kingdom “safest when with one man manned.”30 And in “Love’s Progress,” he details his erotic conquest from his lady’s nose as the meridian between her two suns, to the hemispheres of her cheeks and the treasure islands of her lips, with every kiss as another step into virgin territories he desires to know—and possess.31

Vermeer’s bewitching lute player is another treasure to be looked at, explored, and possessed by a single emperor: that absent lover for whom she is tuning her instrument. Yet, as noted earlier, by pulling us into her realm, the artist reminds us that he, too, enjoyed the pleasure of looking (and painting) this lady as she gently turned the nob on the neck of her lute; and that he, like ourselves, waited for her tune.

This parallel recalls another idea—that geography is a form of history, or a means through which the past can be reactivated into “presence.” This view was shared by numerous mapmakers, including Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598), who extolled atlases as the ideal means of grasping history, since they allowed beholders to locate and envision specific distant events.32 As he would add, as we contemplate a map, its places and associated events become “imprinted” upon our memory, as if we were there, experiencing them ourselves.33

If all painters are, per Ptolemy, geographers of sorts, the map on the wall of this darkly lit interior gains an even higher resonance as a metaphor for the lady, that “little world made cunningly,” and the degree to which we can or cannot know and possess her. At the same time, as an abstraction of the visible world, it reminds us that the room we behold is another kind of map for a past reality that Vermeer once observed and recorded. Though not strictly an Albertian istoria, this painting is a record of history: a view into a temporally distant, yet instantly recognizable human experience, as transitory as the sound we imagine while we continue our silent admiration.34

Again, the crucial point here is that the sound we await will never be heard.35 Renaissance composers of love songs appealed to their ladies to sing, lest their “mute rest” turn them into “mere pictures.”36 As a master of the “mute” art of painting, Vermeer is proposing something else—that his “modern-day Venus” can express her complex feelings just as eloquently in silence. In our desire to hear her, we continue to look and imagine that sound—and it is within this contemplation that we finally grasp the “essential knowledge” he wishes to convey—the desire to bring the “treadmill of time” to stillness. For, as the English composer John Dowland observes in one of his best-known songs for lute:

Time stands still with gazing on her face,

stand still and gaze for minutes, houres and yeares, to her give place:

All other things shall change, but shee remaines the same,

till heavens changed have their course & time hath lost his name.37