Saul and David was regarded as one of Rembrandt’s great masterpieces in the past, but its attribution has been questioned by experts. The painting, which is currently undergoing conservation treatment, has recently been the subject of intensive technical research. This “progress report” about ongoing research on Saul and David highlights current thinking about the painting’s original format; the use of new technologies to investigate the painting; and the challenges in deciding how to treat the painting. The subject offers a telling perspective on how research and treatment of paintings by Rembrandt has changed since Egbert Haverkamp Begemann was a young scholar.

Egbert Haverkamp Begemann was already a fully fledged art historian when he contributed to the catalogue that accompanied the 1969 Rembrandt exhibition organized at the Art Institute of Chicago on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the artist’s death. Characteristically for someone who was to become an important mentor to many of us, he wrote about Rembrandt as a teacher.1 In the same year, a conference was held in Chicago to coincide with a new approach to Rembrandt studies and connoisseurship.2 Horst Gerson’s monograph had just appeared, presenting a radically curtailed reassessment of the artist’s oeuvre, and the Rembrandt Research Project had been established a year earlier.3 At the 1969 conference, technical studies were recognized as a vital ingredient in the evaluation of paintings:

“there is hope that scientific investigations, not only of the paint and the background, but also of the support, will yield conclusive results. They will not answer all our questions, especially when these concern seventeenth-century copies or school pieces; but they will, I am sure, greatly enrich the limited supply of precise standards which connoisseurship has at its disposal.”4

More than forty years ago, it was clear that technical research would not resolve every uncertainty, but in retrospect the optimism in this statement is striking. Advanced scientific analyses have, indeed, changed our view of Rembrandt and have certainly enriched our understanding of the materials Rembrandt used and his working methods, but they have rarely led to “conclusive” results about attribution.

The current study and treatment of Saul and David at the Mauritshuis is an apt illustration of how the technical study of Rembrandt’s paintings has evolved since the 1969 conference. This painting, which was studied thoroughly in the 1970s, has remained one of the most controversial in the oeuvre attributed (or not) to Rembrandt.5 In 2007, the Mauritshuis initiated a new scientific examination of the Saul and David in order to understand the true condition of the work before embarking on treatment of the painting and to shed light on the question of attribution.6

Although the project has not yet been completed, this “progress report” will serve to highlight some of the new examination techniques that experts can now bring to bear and also to describe some of the issues that still dog the treatment of such a complex work of art.

Background to Saul and David

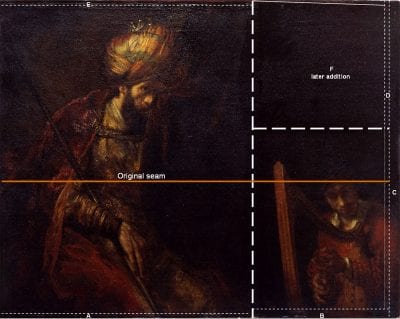

The painting shows two figures against a dark background. At left is Saul, seated holding a spear and wiping his eye on a curtain. David kneels before him at the right playing his harp. The subject of Saul and David is usually considered the moment before the frenzy of King Saul, which twice caused him to hurl his spear at David (I Samuel 18: 9–11) (fig. 1).

Although the authorship of Saul and David has been a bone of contention since before it entered the collection of the Mauritshuis, it became one of Rembrandt’s most admired works, thanks mainly to Abraham Bredius, former director of the Mauritshuis. Bredius bought the painting in 1898 and immediately placed it on loan to “his” Mauritshuis; he left it to the museum in 1946.7 Bredius had a personal stake in the picture — because of his great love of music he identified himself with the figure of Saul8 — and launched such a successful public relations campaign that the painting occupied a place of honor in the Mauritshuis.9 The bubble burst in 1969, when Horst Gerson de-attributed the work, with the devastating comment:

“Ever since this famous picture — which does not have an old history — was acquired by A. Bredius in 1898 for exhibition in the Mauritshuis, it has been hailed as one of Rembrandt’s greatest and most personal interpretations of Biblical history. . . . I fear that the enthusiasm has a lot to do with a taste for Biblical painting of a type that appealed specially to the Dutch public of the Jozef Isaraëls generation, rather than with the intrinsic quality of the picture itself.”10

To no small extent, this assessment is due to the painting’s condition. Although structurally sound, the painting certainly looks the worse for wear. As is well known, at some point in the past the figures of Saul and David were cut apart and rejoined, and a large piece of canvas was added above the head of David. In its present condition, the prominent vertical join and added insert are disfiguring. The two figures are relatively well preserved, although worn in places. The paint surface is heavily flattened throughout, and the old varnish is discolored and cracked. The painting was last restored in Berlin more than a hundred years ago by Alois Hauser, who gave the insert its present dark tone and partially overpainted the curtain.11

Original Format

Recent research into the format of the Saul and David reveals that the painting was originally wider and taller than it is now. Its provenance provides an important clue.12 When Saul and David first appeared in a Paris auction of 1830 as part of the collection of the duke of Caraman, the picture was recorded as measuring “h. 45 p. – 1. 67,” or approximately 121 x 181 cm. The painting was then some 20 cm wider and 5 cm shorter than it is now (126 x 158 cm). In 1869 it was listed in the Oudry sale catalogue with its current size. It is clear, then, that at some point between 1830 and 1869, as Saul and David passed through the hands of various collectors and dealers, it was fashioned into its current format. The faint vestiges of “cusping” (discussed below) at the bottom edge suggest that the painting may even have been cut down before 1830.

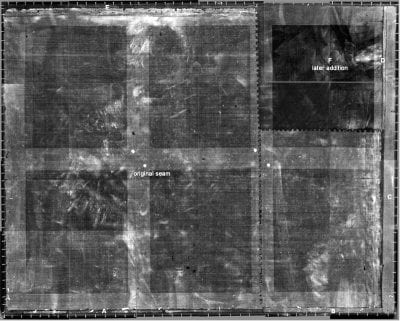

Re-examination of the X-ray taken in the 1970s of the Saul and David shows that the painting currently consists of no fewer than ten separate pieces of canvas (fig. 2). When the figures of Saul and David were rejoined, a large square of canvas measuring 53 x 52/51 cm was added above David’s head in order to replace the lost piece. This canvas, clearly cut from an old painting, has recently been identified as part of an early copy after Anthony van Dyck’s Portrait of Isabella Clara Eugenia, Infanta of Spain (shown dressed in the habit of the Poor Clares), turned upside down (fig. 3).13 The three pieces of the painting were assembled using a very unusual notched join that is, so far as we know, unique in the history of restoration. Narrow strips of canvas added to the upper, lower and right edges in order to enlarge the picture are held in place by the lining canvas.14 The height of the upper piece of canvas without added strip measures 71 cm, which corresponds to a standard loom width of one ell and the lower piece measures 55 cm.15 An original horizontal seam, clearly visible in the X-ray, runs through the figures of both Saul and David, indicating that the two parts of the painting were properly aligned when the pieces were assembled (fig. 4).

Thread counts of the various pieces of linen demonstrate that the linen supports on which the figures are painted are identical. Computer analyses of high resolution scans of the X-rays made it possible to carry out accurate thread counts of the narrow strips.16 From this we can conclude that strip B derives from the original painting, and that the linen of strips A and E is identical to that of the insert at top right, indicating that they were added at the same time. Both of the strips added on the right side — the vertical strip C and the narrow strip D — appear to have been added in a subsequent lining, at the same time that the right tacking edge of the David segment was flattened in order to widen the picture (see fig. 2 and fig. 4).

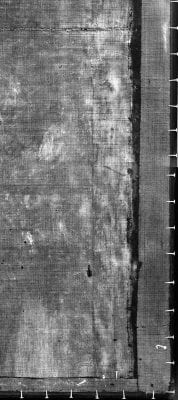

The X-ray also reveals substantial deformations known as “cusping,” caused by the initial stretching of the linen support on a frame, on three sides.17 Computer analysis indicates that at least 10 cm is missing from the lower edge — suggested by the faint tips of cusping just visible at the bottom of the weave angle map (fig. 5 Top). A comparison of the pitch of the cusping at the left and right edges suggests that about 5 cm has been lost at the left. It would appear that only a few centimeters have been trimmed from the top edge. The depth of cusping is vividly illustrated in so-called false-color “weave angle maps,” which graph the deviation of the angle of the warp and weft threads in the linen support respective to the true vertical and horizontal (fig. 5).18 This new computer technique demonstrates that the original right edge of the David segment is intact and that the bottom edge of the painting does not show the same degree of cusping as the other edges, indicating that the bottom of the picture has been cut down. That this edge has been reduced is also consistent with the truncated figures of Saul and David.

The original right tacking margin of the segment of canvas containing the figure of David provides important new evidence of the painting’s original format. This edge, which is visible in the X-ray, is obscured by thick overpaint on the paint surface. Different types of holes corresponding to preparation of the canvas and lacing holes corresponding to the primary cusping are also visible along this edge in the X-ray (fig. 6). If we assume that the width recorded in the Caraman sale catalogue of 1830 is correct (181 cm), approximately 18 cm must have been lost in the center of the picture along the vertical join when the figures were cut apart or put together, taking into account that only some 5 cm has been lost from the left edge. Close examination of the canvas weave on either side of the notched vertical join in the high resolution X-ray shows that the prominent weave faults at the left edge are not present at the right edge (fig. 7). This proves that canvas is missing along this join and, along with other information discussed above, suggests that the original format was ca. 145 x 181 cm, as compared to the present 126 x 158 cm of the original canvas (without present additions).19 The painting was probably originally composed of two strip-widths of one ell joined by a horizontal seam. The missing strip of canvas between the two figures helps to explain the spatial incoherence between the figures in the picture. Figure 8 shows a possible reconstruction of the Saul and David’s original format.

Authenticity of the Curtain

Horst Gerson criticized Saul and David particularly for the curtain between the two figures.20 Volker Manuth, who is part of the international advisory committee involved in the technical examination of Saul and David, also called the authenticity of the curtain into question during discussions about the painting.21 Re-examination of this area of the painting using both traditional and novel investigative techniques has been particularly fruitful in assessing this issue.

Microscopic Examination

Examination using the stereomicroscope has revealed that the majority of reddish brown brushstrokes used to depict the folds in the curtain are not original. The paint flows into old paint losses and covers many cracks and also extends on top of the added strip at the upper edge. The areas of the curtain close to the figure of Saul do appear authentic, although here a thin translucent glaze has been added, providing a transition to the more heavily restored areas closer to the join.

Infrared Reflectography

Infrared Reflectography (IRR) reveals the extent of the overpaint in the background (fig. 9).22 The overpaint, rich in black, appears dark in IRR due to its absorption of infrared. The overpaint has been freely extended in broad brushstrokes over the curtain/background between the two figures and around the head of David.

Paint Sample Analysis

A number of minuscule paint samples from carefully selected areas of the curtain and background were extracted to determine the materials and build-up of the original paint and the nature of the overpaint (fig. 10). The paint samples were embedded in polyester resin and polished to reveal a cross-section showing the paint layer build-up and allowing pigments to be identified with analytical methods. The ground, and curtain paint, which contain pigments such as smalt, red lake, and earths, were found to be characteristic of Rembrandt paintings.23

Elemental Mapping

Since traditional investigative techniques — X-ray and IRR — provided very little information about the original paint layers, a novel imaging technique was used to investigate the area of the curtain between the two figures. Scanning macro-X-ray fluorescence analysis (MA-XRF) using a mobile scanner developed by the universities of Antwerp and Delft provided elemental distribution maps of the curtain area. The so-called contrast images show the distribution of elements present in the pigments that make up the paint. Since only the curtain contains the pigment smalt and the overpaint does not, distribution maps of the elements cobalt, nickel, and arsenic present in smalt were particularly effective in providing an image of the curtain hidden below the overpaint and discolored varnish (fig. 11).24 The results succeeded all expectations, revealing that the curtain is part of the original design and moreover, that it is largely intact, except for a narrow strip along the vertical join and scattered losses at top and bottom.

![Fig. 11 Cobalt (Co-K) distribution map (XRF scanning) from the pigment smalt in the original curtain; associated nickel and arsenic maps not shown (from Noble et al., Technè 35 [2012]: fig. 3D)](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/GordenkerNoble5.2_fig11-400x318.jpg)

Authorship

The attribution of the picture is still not fully resolved. In 1969, many eminent scholars, including Jakob Rosenberg, criticized Gerson’s rejection of the painting.25 In 1978, De Vries, Tóth-Ubbens, and Froentjes argued that the stylistic inconsistencies in the picture could be explained by the fact that Rembrandt painted it in two phases, in the mid-1650s and the mid-1660s.26 Weaknesses in the painting convinced other scholars that it could not have been painted by Rembrandt. Henry Adams suggested an attribution to Karel van de Pluym (1625–1672) in 1984.27 Christian Tümpel proposed that an unidentified Rembrandt pupil had painted the picture.28 In 1993 Ben Broos tentatively gave the work to Willem Drost (ca. 1650–after 1680),29 but Jonathan Bikker subsequently rejected this attribution.30

It now seems certain that the picture was painted in Rembrandt’s workshop, given the similarities of the ground and composition of the paint to that in other pictures and the existence of related drawings (Benesch C.76, 947, 948). One possibility is that it was painted in the workshop by a pupil after Rembrandt’s design and that Rembrandt revised or helped to complete the composition.31 Many scholars have been reluctant to accept the idea that Rembrandt worked collaboratively with his students, except in rare instances (e.g., The Sacrifice of Isaac, ca. 1635; Alte Pinakothek, Munich; inscribed as being retouched by Rembrandt). However, several collaborative paintings or paintings retouched by the master are described in the 1656 inventory of Rembrandt’s possessions: six are listed as being “retouched by Rembrandt” and two as being “painted over again by Rembrandt.”32 Ernst van de Wetering, who is also part of the international advisory committee for the Saul and David, has stated publicly that he believes the painting to be by Rembrandt himself, executed around 1646 and 1652.33 The further study and treatment of the painting, which is now underway, might well help to confirm this new opinion.

Treatment

The condition of Saul and David and the recent findings present the Mauritshuis with something of a dilemma, as there is no easy way forward. We have decided on a careful and gradual removal of the varnish and the overpaint, informed by the new research and the attempt to improve the current appearance, but only time and continued examination will determine the final extent of the treatment. The results of recent research have told us much about the painting’s material history, but in some ways they make the challenge of restoring it more complex than ever. An exhibition in 2015 will present the painting’s intriguing material history.

Conclusion

Much has changed since the Rembrandt symposium of 1969. For the Saul and David, new investigative techniques have made it possible to answer a number of outstanding questions regarding the picture’s condition, questions that were left unanswered in earlier investigative campaigns. We now know its original format and have a good idea of the condition of the curtain in the background. The optimistic predictions that scientific investigations would lead to “conclusive results” about the authorship of the many paintings attributed to Rembrandt have, unfortunately, not been fulfilled, but such research certainly has had an impact. As the example of Saul and David shows, technical studies have opened up new avenues of scholarship through which we not only evaluate authorship but also make more informed choices as to treatment and display. We can no longer make judgments about attribution based solely on traditional connoisseurship but must consider various kinds of information, including scientific analyses. One question will, however, remain unanswered: What would Rembrandt have thought of all of this?

![Fig. 11 Cobalt (Co-K) distribution map (XRF scanning) from the pigment smalt in the original curtain; associated nickel and arsenic maps not shown (from Noble et al., Technè 35 [2012]: fig. 3D)](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/GordenkerNoble5.2_fig11-112x84.jpg)