This second installment of D. C. Meijer Jr.’s article on Amsterdam civic guard portraits, “De Amsterdamsche Schutters-stukken in en buiten het nieuwe Rijksmuseum,” focuses on the painting known as the Nightwatch: Rembrandt’s Company of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch, 1642, in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.The article was originally published in Oud Holland 2, no. 4 (1886): 198–21, the second of five installments.

Part II1

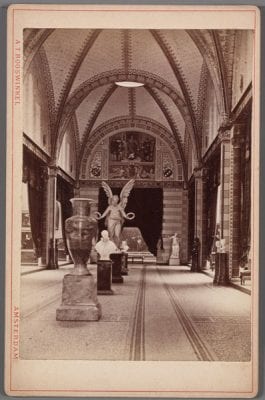

As soon as we enter the front hall of the museum and turn our backs toward the English stained glass, we perceive, through the visitors who flock to the Hall of Honor, a figure in a bright yellow garment. Coming closer, we recognize the lieutenant of Rembrandt’s civic guard portrait. It is Mr. Willem van Ruytenburg, lord of Vlaerdingen en Vlaerdinger-ambacht. Do not be alarmed, esteemed reader! Despite the high-sounding title, this is simply an Amsterdam burgher whose father Pieter, married to Aeltje Pieters from a branch of the Bicker-family, bought the peerage property Vlaardingen from the Prince of Aremberg in 1611. The family probably stemmed from the grocer Jan Michielsz, who lived in the house called Ruitenburch, on the corner of the Warmoesstraat and the present Vijgendam2 in 1571; but the family soon rose to an honorable role among the eminent Amsterdam families. Pieter became a board member of the Orphan Chamber (College van Weesmeesteren) in 1617. His son became a member of the city council from 1639 and an alderman starting in 1641. Perhaps through his wife, Alida Jonckheyn, but definitely through his sisters, he was an in-law to the Pauw family, because Anna was the second wife of the grand pensionary3 and Christina’s second marriage was to the latter’s brother Reinier, and his daughter married one of Willem Ruytenburg’s sons. Another son, who had dedicated himself to the soldier’s life, married a sister of no less a person than the Lord of Nassau-Ouwerkerck.4

The lieutenant carries his partisan in one of those daring foreshortenings with which Rembrandt sharpened his skills. Next to him walks the captain, holding his cane as a sign of dignity, and clad stylishly in black, with a heavy dark-red sash draped around the neck. It is Frans Banning Cocq. When still a boy, his father Jan Cocq might have come to Amsterdam from Bremen, poor and needy, but his family ties to the Hooft family and his marriage to the rich heiress of Frans Banning5 guaranteed his fortune and gave his eldest son the right to compete for the hand of one of the daughters of the proud Burgomaster Volkert Overlander. Overlander was raised to the nobility by King James I of England in 1620 and became Lord of Purmerland and Ilpendam (through acquisition). The marriage was consecrated by Otto Badius (Vondel’s “Otter in ‘t Bolwerck“)6 and, the harmony between both families was so good that when the old burgomaster passed away on October 18, 1630, he was buried from Jan Cocq’s house. The latter soon followed him to his grave. This meant that Frans Banning Cocq had the task of guarding the honor of both families, because his only brother Jan Cocq (who drowned in the IJ in 1658) was deaf and remained unmarried and his only brother-in-law worshipped Bacchus over Hymen. Frans, however, remained a genteel patrician, who usually sided in political matters with Cornelis de Graeff, who for only a few weeks (Nov. 1633 until Jan. 1634) was husband to his [Frans Banning Cocq’s] wife’s sister. In 1634, Frans became a member of the city council. His dignity as a burgomaster and his knighthood were then still in the future, but he ensured the immortality of his name by connecting it to one of the greatest masterpieces that was ever created by the brush. As it has become clear to me from his family documents, Frans Banning Cocq was an art lover,7 but his greatest service to the arts came when, as captain of the civic guard squad of district 1, he voted to commission the portrait for that district. This would serve as decoration of the newly built Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall [Kloveniersdoelen], to be assigned to Rembrandt van Rijn.

Rembrandt van Rijn

And still, maybe there was a more prosaic reason for this commission than Cocq’s appreciation of Rembrandt’s artistic genius. Perhaps Rembrandt’s eccentricity and willfulness could have caused the civic guards to look for less highly gifted but more pliable natures among the many painters of Amsterdam. But after all, Rembrandt in 1639, and maybe still several years later, lived “op de binnen-Emster in die suijckerbackerij” [on the Inner Amstel in the confectionary].8 And from there, district 1 stretched along the city walls (currently the Herengracht) and along the Singel on toward the Warmoesgracht. Maybe we have to thank Rembrandt’s temporary domicile just as much as his mastery. That mastery was by then already fully radiant even though the artist was not yet esteemed by everyone. As a result, perhaps he was offered the opportunity to deliver proof of his abilities in the area of the civic guard portrait. How wonderfully successful was that proof!

How [marvelously] the master showed his superiority, not only, as he did everywhere, in conjuring with light and dark, with glow and color, but also with composition! How masterful was the solution to let both officers walk in front some distance, with Cocq deliberating weightily and Ruytenburgh listening attentively! As a result, their dignity was not impaired, so that the troops move behind them on a stage full of life and movement, full of nature and truth, enhanced by the banging of muskets, the drumbeats, the waving of banners, and rattling of spears!

And where the feeling of nature and truth, obeyed in naive simplicity, prescribed that with such a street scene neither children nor dogs could be omitted (in contrast to Van der Helst, who included the portrait of the little son or the beloved spaniel of one of the officers), there appeared a delicate taste that kept, on both sides, the dog barking at the drummer and the little rogue with helmet and powder horn in shadow. He elevated these details into high poetry by letting the full light fall onto the idealized, richly dressed child-figure, a quick lass with golden blond tresses who skips between the civic guards. She was not a daughter of the captain: Frans Banning Cocq did not have children. But I do see a witty allusion to his name in the white cock.9 Italian painters would perhaps have substituted an angel flying through the air with his family escutcheon.

What is the subject of our painting? The name Nightwatch can be rejected totally; nor can we accept Sortie des arquebusiers [Departure of the Arquebusiers].10 In this painting, just as in the other civic guard portraits, pikes are depicted, not just arquebuses.

According to the caption of the contemporary drawing, reproduced with this article (to which we will return later), the captain orders the lieutenant to let his company march forward. There is no word of target shooting. Furthermore, I don’t think it was still the custom then to march out with all the company fully armed in order to shoot targets. When this happened civic guards and non-civic guards did it as amateurs, at the target range.

The civic guard portraits are in the end, with some exceptions, neither history portraits nor depictions of facts, although now and then, perhaps even often, certain historical facts – such as an entry – were introduced to give civic guards ideas of how to remember themselves. Basically, though, they are simply groups of portraits to which the painter sometimes attached, from his imagination, one or another action to enliven the scene.

Neither is it right to speak of a Korporaalschap.11 The fact that the number of depicted figures in the civic guard-portraits usually corresponded approximately to the strength of a “korporaalschap” will have been the reason for that word. But after all, we always see the complete staff [officers] of a company present. Let us therefore follow the example of the notary Spithof, who in making an inventory of the goods owned by the Longbow Archers Civic Guard Hall, wrote: “Two large painted portraits, being corporaelschappen,” and then crossed out this last word, substituting “companies” instead.12 This is also wrong, because the complete company is never depicted. The only correct designation (if one does not want to use the term civic guard portrait) is Schuttergezelschap, which can be followed by “from district 1 or 2” or “with captain A. or B.” etc.13

The civic guards are departing from a gate. Asking which one is unnecessary, for the Regulierspoort, is the only one that would qualify for this civic guard district and it is not that gate. But Rembrandt needed a bridge with steps for compositional reasons, in order to make the groups in the back rise above the ones in the front in a natural way. Since no bridge in Amsterdam qualified,14 he chose fantasy architecture.15 Nevertheless, he surely meant a city gate. He even constructed a piece of the adjacent city wall with an arch under which water flows into the city moat. On the wall, he placed three more figures (two men and a child). Yet because this section of the painting is cut off, the bridge railing, ending in a knob near the figure of the small boy, has disappeared. The other side of the painting also lacks a section, but in this case only a small strip containing the neck of the drummer. Likewise a strip has been cut from the top and the bottom.

Why and when did this vandalism occur? To answer this we have to follow the life of the painting. Parenthetically, I will add that foreigners have named it “the Nightwatch” in the last century, a rather stupid title that Dutchmen irritatingly have adopted.

Rembrandt’s civic guard portrait was painted for the Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall (Kloveniersdoelen). The catalogue of the Trippenhuis and Vosmaer’s work include the label Crossbow (!) Archers Civic Guard Hall (Voetboogsdoelen) (a small spot on that thoroughly gigantic work).16 Perhaps this error originated from reading the name of Banning Cocq in Commelin’s Beschrijving van Amsterdam (fol. 664), where he mentions the names of the governors in Van der Helst’s chimneypiece for the Longbow Archers- (erroneously Commelin wrote Crossbow-) Civic Guard Hall (Van der Helst’s portrait used to hang in the Trippenhuis (no. 119 in the catalogue).17 It is quite clear that Rembrandt’s painting could hardly have served as a chimney piece. I do not have to bore the reader with any discussion that the Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall (Kloveniersdoelen) was the original place of Rembrandt’s masterpiece, since Schaep’s list18 has established the fact beyond doubt, and it is also mentioned in the second edition of the catalogue of the new [Rijks]museum.19] The great hall of the Arquebusiers civic guard headquarters was a long rectangle. On one of the short sides hung the large portrait by Van der Helst, which has now been transferred from city hall to the new [Rijks]museum (Rembrandt Hall, no. 37 of the new city numbering).20 Opposite was the chimney with the governors’ portrait by Govert Flinck (no. 31, as above) [fig. 10 in the translation of G. Schaep’s notes].21 The civic guard portraits by Flinck and Joachim von Sandrart, which are nowadays in the Rembrandt Hall flanking the entrance to the Hall of Honor, used to hang on both sides of the chimneypiece [the governor’s portrait by Flinck] [fig. 11 and fig. 12 in the translation of G. Schaep’s notes]. Three large portraits hung (opposite the windows) on one of the long sides: two of these paintings are nowadays still present in the city hall in the council hall.22 The third, the Rembrandt, was closest to the fireplace.

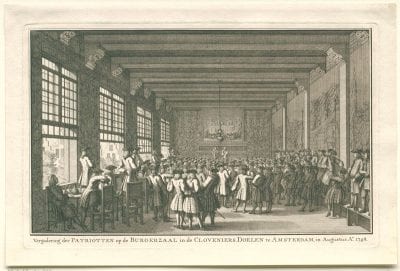

Did the smoke that blazed from the large peat fires in these chimneys damage the paintings, with Rembrandt’s suffering the most? But in other ways, too, the hall (or the way it used to be) was not favorable for the conservation of the artistic treasures. Civic guard halls had slowly become inns, and it was usual to go to the halls to drink a pint of wine and see the paintings at the same time. Along with wine came tobacco pipes and, worst of all, meetings were held there, the kind we nowadays call political meetings, in 1672 and 1748. It is therefore no surprise that when the city government finally took over the care of the paintings and brought them to city hall, it was thought that the portrait had become “overteert” [literally: tarred over], according to the notes of the restorer Jan van Dyk.23 He also added that he cleaned the portrait of the many “cooked oils and varnishes that from time to time had been brushed over it”; with this cleaning the shield with the names appeared, which had previously been invisible. Van Dyk was rightly proud of his dévernissage, and, moreover, it was only since that time that the portrait, which he highly praised, started to draw the attention it deserved. He also mentioned the important detail of the mutilation with the following words: “It is a pity that this portrait has been cut so much to fit between two doors (!!),24 because on the right hand there used to be two more figures and on the left the drummer was depicted in full, as is visible in the true preparatory sketch now in the possession of Mr. Boendermaker.”25

One has to be a very distrustful critic to doubt the truth of the statement which Van Dyk wrote in 1758. In 1748, the portraits of the long wall were still in the civic guard hall, according to a rendering of the meeting held there, engraved by S. Fokke.26 How can one believe that Van Dyk would erroneously have mentioned that cutting as a fact, while it was only ten years previous that he and his readers could have seen the painting for themselves in the civic guard hall? The cutting could not have happened before that time, because in the civic guard hall the Rembrandt, according to this print, was not hung between two doors. It must therefore have happened when the portrait was moved to the Small War Council Room in the city hall, where it hung, according to Van Dyk, opposite the chimney. That Small War Council Room was located on the upper floor of the building, in the southern-facing part of the west facade. The doors are still present; the space between both door frames is nowadays 405 cm. The western door, however, is partly “blind”; if one measures the width between the doors as it appears to have been in the last century, then one gets 452 cm, the present width of Rembrandt’s civic guard portrait is 435.27 These sizes do not contradict my conviction that the two doors that Van Dyk mentions are indeed the doors of the “kleine krijgsraadkamer.”

But there is more. As I said, three paintings hung next to each other in the Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall (Kloveniersdoelen). The others are, according to the city catalogue, 525 and 497 cm wide, though the Rembrandt is only 435 cm [fig. 9 and fig. 10 in part on the this translation of Meijer].

Schaep’s list indicates that it did not hang in the middle. Thus such an asymmetrical arrangement would be impossible to explain. The portraits were probably all intended for the decoration of the hall (circa 19 meters long and 11 meters wide) and from the arrangement of the other portraits it appears that the hall formed a well-ordered entirety. Even the beams correspond with the size of the paintings on the print mentioned earlier, although I do not wish to attach too much weight to that, because, Fokke, usually accurate, even depicts the floral wallpaper next to the chimney that replaced the portraits by Flinck and Sandrart (which were earlier removed); he shows four portraits on the long wall, instead of the three that were present according to Schaep’s list.

I am not sure if A. D. de Vries had thought of the argument about the measurement of the paintings, but other arguments were not unknown to him.

The heraldry exhibition held some years ago in The Hague28 showed a very important album: two volumes in oblong format (19 x 15 cm), containing the “genealogy of the lords and ladies of Purmerlant and Ilpendam, by blood and affinity.” With those lords and ladies one should not think of a noble family whose lineage goes back to the Crusades, but simply of Frans Banning Cocq and his father-in-law Volkert Overlander. The album contains genealogical and historical notes relevant to the family. One of the notes mentions a “sketch of the painting on the large hall of the civic guard hall, depicting the young Lord of Purmerlant, as captain, giving orders to his lieutenant the Lord of Vlaerdingen to let his company of burghers march.” It is our “Nightwatch,”29 indicating the cut-off parts that I described above; it is impossible that this drawing that Mr. Banning Cocq had made for his family album would have included an addition that did not appear on the original portrait in the civic guard hall!

The happy owner of the album, D. De Graeff van Polsbroek Esq., a descendant of the heirs of Cocq, was friendly enough to grant us permission to take a photograph of this important drawing; therefore we can offer it to our readers.

Probably readers will ask: how is it possible that, in spite of all this, A. D. de Vries doubted so long that a part of the painting had really been cut?

I suspect he [De Vries] feared that Van Dyk had put too much emphasis on the “true model now in the possession of Mr. Boendermaker.” If this, as Van Dyk apparently thought, was the original preparatory sketch, or at least an accurate reproduction, then there should be no difference in those parts that were not lost. And this difference does exist; the portrait of what Van Dyk called the “true model” is in the National Gallery in London, nowadays generally considered to be a work by Gerrit Lundens.30

This Gerrit Lundens, whose copy plays such a large role in the history of the Nightwatch, was a painter of peasant scenes, etc., according to the notes by A. D. de Vries.31 His mother was probably a daughter of the famous wood-engraver Christoffel van Sichem. He was born in Amsterdam around 162032 and married Agnietje Mathijs in 1643; in 1667 he was still alive.33 He never painted for the civic guard halls. His depiction of the company of Banning Cocq, which sold for f 263 in the sale of Van der Lip, 1712,34 was no civic guard portrait, but rather, a copy. De Vries’s hypothesis was probably correct. The copy was given to the National Gallery London in 1857 as a work by Rembrandt himself, having come from the cabinet of the counts of Orsay and Hohenzollern,35 on whose sale in 1810 it was withheld, after having been described in the catalogue as “l’esquisse très fine de la Ronde de nuit de Rembrandt, provenant de la vente Randon de Boisset” [the very fine sketch of the Nightwatch by Rembrandt, coming from the sale of Randon de Boisset]. The latter auction took place in 1777; the portrait was then attributed to Gerard Dou. The Boendermaker collection had been sold in 1768, and it is very likely that the painting that Randon de Boisset owned was the “model with Boendermaker” that Van Dyk mentioned.36 But even if one wants to adhere to the judgment of the eighteenth-century connoisseurs that the portrait with Boendermaker was by Rembrandt, then the argument grates even more; because then two paintings would have existed, which, regardless of whether one was an original sketch and the other a contemporary copy, proved by their concordance with the drawing in the album that the mutilation had indeed occurred.

Lundens’s picture was also noticed by the French connoisseur Durand Gréville, who had a photograph taken and, after comparison with the original, published something about the mutilation of the Nightwatch in the Revuepolitique et littéraire of November 3, 1883.37 In November 1885, after Abraham Bredius had also presented the mutilation as a fact in the catalogue of the new [Rijks]museum,38 he returned to the matter. In the Gazette des Beaux-Arts he even published a sketch showing how the Nightwatch had looked and how it is now.39 This sketch to me seems to have been made, rather, after the engraving by Claessens, and not after the photograph of the Lundens picture, because two men appear on the wall and not the child. According to his calculation the measurements (now 4.35 x 3.59 m) used to be 5.02 x 3.87, which fits well with the measurements of the other portraits in the Arquebusiers Civic Guard Hall. He expressed the hope that we would retrieve the cut strips. That hope is probably in vain; if they had not been too damaged to keep or sell, they would have reappeared by now. It was likewise an illusion to expect a “document d’archives” [archival document] “qui concerne Lundens“[that concerns Lundens]. This however is superfluous, because the case can be considered sufficiently proven.

But now [I report here] the differences observed by De Vries between the Lundens and the remaining piece of the large painting:

On the London copy the drum has more labels. One notices the shadow of Ruytenburgh’s spear; the man who averts his gun has four straps on his garment; one can make out the masonry joints in the building’s wall and the window frames; the girl in the back is more clearly visible, and the nameplate is omitted. All of this, however, does not seem weighty enough to suppose that Lundens in making his copy would have permitted himself to add two portraits and a piece of wall and bridge (which totally shifts the center point of the painting), if this had not also been present in the original. Added to that one has to suppose that the drawing in Banning Cocq’s album would show the same deviation (while in other aspects it appears not to have been drawn after the small painting; the drum has, for example, four labels on it, just as on the large portrait) and that Van Dyk in 1758 did not remember what Rembrandt’s painting had looked like in the civic guard hall.

The question has been confused somewhat by the appearance of the engraving by L. A. Claessens in 1797, which displays the painting in an unmutilated state, and thus could prompt the opinion that the cutting had only taken place later.40 This is out of the question, however; from precise comparisons it became clear to A. D. de Vries that Claessens had used the copy by Lundens or a similar one, and in such a way that the first state looks much more like it than the second, he probably worked first from that for the sake of convenience and afterward, comparing his work to the large painting, made some changes, keeping the cut-off part.41

The answer to the question, how Claessens could know the old copy in 1797, while it was in foreign possession, is probably given through a drawing by J. Cats [fig. 10], which was found by De Vries and which was published in the Handelsblad of Jan. 12, 1884, through an impertinence that was very unpleasant to him.42 This drawing was, except for some small things, completely similar to the painting by Lundens, and it was probably the one that was used by Claessens.

The last that De Vries wrote on the question were the words: “It is clear that no piece has been cut from the Nightwatch after 1758, but before [that year]…?” On my own behalf, based on the above arguments, I leave the question mark with peace of mind and [I will] now commence with the discussion of other points calling for attention, when comparing the older copies with the present state of this world-famous portrait.

It is an exaggeration what Durand-Gréville writes in his article in Revuepolitique et littéraire43 and repeats in the Gazette des Beaux Arts, 1885.44 Neither in the London painting nor in the large portrait are the garments of the young girl or the doublet of the lieutenant white, as De Vries asserted.45 But considering the hair of the girl, he [Durand-Greville] is rather correct, the general tone has become somewhat darker and reddish brown.

“Worthy of wonderment as regards the strong sunlight” is written in the Catalogue Boendermaker and from that Mr. Durand-Gréville (p. 412) concluded that the Nightwatch itself might originally also have been painted in a clear fashion. Although everybody will agree that the thick impenetrable, shaded parts are not what Rembrandt originally wanted, and that the effects of time, smoke, and varnishes give the painting presently a different effect than it originally had. One would, in my opinion, go too far to assume that Lundens’s copy precisely reproduces the original tone and color. There cannot be undeniable proof that the civic guard portrait — having slowly transformed into a “Nightwatch” — was originally painted in full and clear daylight. Everyone will agree that the painting in London gives an entirely different impression — to the extent that the Amsterdam painting appears as if one saw the London painting through a brown window. But who will assume that Lundens in his copy has expressed all the mastery of Rembrandt over light and tone or that he has displayed everything that Rembrandt conjured on the canvas? Is one allowed to say, while there is only a copy of that tone, that the civic guard portrait by Rembrandt was “une peinture jadis très claire et très sage” [a painting once very clear and very wise]?; and discard and hold untenable the remarks by Charles Blanc and Vosmaer so well summarized by Victor Hugo’s beautiful expression “Rembrandt travaillait avec une palette, toute barbouillée de rayons de soleil” [Rembrandt worked with a palette all daubed with sunbeams]. It appears to me that this will not go! It is truer, I think, that the smoke stains and the yellowed varnish have not impaired the enchanting impression and the mysterious poetry of Rembrandt’s masterpiece but rather have augmented it.

One can probably agree with Durand-Gréville, however, that the trimming has harmed the painting. Originally, the composition was less compact, he justly writes; there was more air in it. Had Fromentin known the painting in its original form his reproaches might have remained in his pen.46

Now that we know that Rembrandt depicted his civic guards on a bridge near a wall, with a gate as the background, the last grounds for the assumption that the scene plays in a large hall, in which the light falls through high windows, has disappeared. One will have to imagine that the shadow in the foreground, into which the small lad disappears, was caused by a thick group of trees before and to the left of the bridge.

The third point that draws attention when comparing our civic guard piece with the old copies is that there are a couple of details that feed the assumption that the present part has not survived completely unharmed either. In the painting by Lundens, as well as in the drawing by Cats, the smoke coming from the shot fired behind the officers is clearly visible along the sash and the collar of the captain. It seems to me,47after precise studying of the portrait as we know it now, that smoke used to be there as well. Also the physiognomy of the civic guardsman right above the captain, which gives no one any pleasure, is in Lundens’s copy and in Cats’s drawing and in the album of Banning Cocq another person [altogether] and his hat is less high. It is also curious that the flag in all three copies has five rather than four bands (fesses). The upper fess is nowadays orange. On top of that is another fess in the old copies [but not in the actual Nightwatch]; that [top fess] is, just like the bottom fess of the color that became green in the Lundens and shows as blue in the album drawing. (The white that Mr. Vosmaer mentions among the colors is not present.) The knob on the flagpole is somewhat different and, as we already mentioned, the plate with the names is missing.

That last detail sheds new light on the wonderful discovery, mentioned on page 91 of the third year of this journal,48 that for at least one of the persons portrayed in the Nightwatch — who paid for his inclusion — the name is missing on the plate. In the present state of the Nightwatch there are at least seventeen [portraits] and before the mutilation [of the painting] there were nineteen. The list of names [on the painted plate] numbers only sixteen.49

The most probable solution is that when Van Dyk rejoiced that he had found the shield with names during his cleaning, he surrendered himself to the illusion that the shield had been painted “by Rembrandt himself.”50

Such name shields never occur in civic guard portraits,51 although we are dealing here with a painter who allowed himself exceptions, and it was his right to do so. But that prosaic nameplate, in spite of its inventiveness, is architectonically unmotivated, given its placement on the arch of a gate; this is an eccentricity not of the kind that we can deem possible in a Rembrandt painting.

The nameplate will have been added later and a few civic guardsmen, whose names were forgotten (or… who could or would not pay for it) are missing.52 Whatever the case, we now know that when the names that have been applied to the frame in the new [Rijks]museum must be renovated again (which I hope not!!), given the glare that they experienced with the opening of the building, it [the frame] will have to be supplemented with the name of Nicolaes van Cruysbergen, provost.53 One should also correct the first name of Bronkhorst: his father did not have the impossible name of Metes or Meter, but was simply called Pieter. The other variations are less important. There is also a list of names on the drawing by Cats and another pasted on the back of the painting by Lundens. Both are written in eighteenth-century handwriting,54 more or less sloppily copied after Van Dyk, although they [both] leave out Cornelissen after the name of the ensign.

The ensign is one of the few sitters about whom we know a bit more than the name. Almost surely, he is the “Mr.Jan de Visscher, ensign of the civic guard in Amsterdam,” Jan Vos’s epitaph for him when he died during the attack on Amsterdam by Prince William II:

Dus ziet men Visscher, die het vaandel heeft gezweit:

Maar toen het woeste heir de Stadt aan ‘t Y deed vreezen,

Heeft hy van spyt zyn vaan en leven afgeleit.

Zoo toont de jongling zich van Bikkers bloedt te weezen:

Dien Bikker, die zijn staat, tot heil van ‘t volk, verliet.

Een vrye ziel gedoogt niet dan een vry gebiedt.55

The expression “Bikker’s blood” needs to be taken figuratively. In the genealogy of Bicker, I do not find the name of the ensign.

Labeled a drunk in later ages,56 the poor drummer paid dearly for the honor of inclusion by Rembrandt. But he did not survive for long: only a couple of years later someone else took his honorable place in the company of Banning Cocq.

We have followed Rembrandt’s civic guard portrait into the Small War Council Room in the former city hall. Now at last more words [can be said] about its further fate.

When, during the transformation of the city hall into a palace, most of the city’s paintings were brought to the Prinsenhof; it stayed there with a few other portraits, first becoming part of an exhibition, and then in 1815 it was brought to the collection of the Trippenhuis [forerunner of the Rijksmuseum]. It was there that The Nightwatch underwent the dangerous operation of relining. Mr. Hopman reaped the thanks of all art-loving Europe for that.

In light of the rising fame of the Dutch school of painting, the desire became intense to found a worthy museum. The desire was satisfied in the following way. In the early morning of July 6, 1885, Rembrandt’s masterpiece was silently brought from the Trippenhuis to its new home. That transfer should have been a triumphal procession, joined by everyone in the Netherlands who is or should be interested in the arts. And it could have become that, because truthfully, nothing had been withheld in the new room as regards making it a temple for the sovereign of our school of painting. Unfortunately, those good intentions did not assure a good result, at least not in the eyes of many. So long as the Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp does not flank one side of the civic guard portrait [The Nightwatch], [with] the Syndics of the Cloth Guild on the other side, until then the size of the room would seem to be intended to display our poverty rather than our riches. The biography on the frieze around the whole room is inappropriate, as the room needs to be filled with paintings by other masters. Moreover visitors are indifferent to the gilded statues on the stone columns; they come only for Rembrandt’s art and they just ask for a dignified placement [of his paintings] in a surrounding that least distracts the eye, and in light that best brings forward their beauty. Considering the first [problem], that demand has been satisfied by placing the decorations high enough. The painting has also been lowered and thus hung like a tableau de chevalet [easel painting]. That continues the effect that had become so dear to every admirer of Rembrandt in the Trippenhuis. Considering the lighting: with Rembrandt we have the special fortune — something that cannot be said of every master to his progeny — to have his own instruction on how he wished his works to be exhibited. “”Hangt dit stuck op een starck licht” [Hang this piece in a strong light] he wrote about one of his paintings to Huygens on Jan. 27, 1639.57 But at a time when museum rooms with sky lighting were not yet known, he did not mean by “Hang in a strong light”: “pour a stream of strong cold light over the smooth barren floor between the spectator and my piece!” After all the study conducted lately to arrive at solid data for the appropriate lighting of paintings, one would have expected something different in the [Rijks]museum than what the Rembrandt Hall now has to show.58

But Rembrandt is elevated above that! Whatever the lighting, his genius will conjure sunshine on his canvas that will beam out! No artificial means is needed to help him! In either the cool, solemn surroundings of the museum hall or in an atmosphere of comfortable [gezellig] bustle, [Rembrandt’s picture] knows how to captivate the spectator, to enchant him, and to move him into another world, sparkling with warmth and life, of glow and color!