A hitherto unknown coconut cup from Dutch Brazil with carved representations sheds new light on the furthering of knowledge through pictorial representation that Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen promoted in the mid-seventeenth century to add luster to his official image. Featuring representations of cannibals and “civilized” aboriginals, the cup suggests that “savage” Brazil was “civilized” under the peaceful leadership of the Protestant count. The same political message recurs on several other Brazilian artifacts once owned by Johan Maurits, who deliberately deployed his exotic Kunstkammer objects as diplomatic gifts to enhance his reputation as governor-general of Brazil. But when objects are integrated into a different collection context, they undergo a connotational paradigm shift. This process is easy to see in the provenance of the carved coconut cup. By the time Alexander von Humboldt owned the cup (ca. 1800), its political message had long since been obscured. Rather than an object attesting to political power, the carved coconut cup, like other “Brasiliana” from Johan Maurits’s collection, had come to be regarded as an objective illustration of Brazilian natural history.

Beginning with the Renaissance, Kunst- and Wunderkammers confronted visitors with objects that were not only curious, rare, and precious but also informative about their owners: how they viewed themselves and what their aspirations were. This was especially true of collections owned by reigning princes, in which the exhibits were intended to attest both to the powers of divine creation and humans’ artistic potential and to the role played by the prince in shaping the society he ruled. Whereas portraits on the wall illustrated the integration of the ruling dynasty into the spheres of politics and scholarship, scientific instruments and other precious artifacts positioned the prince closer to divine wisdom. Concomitantly, they demonstrated that the ruler was in a position to define his territory by opening it up through science, to keep it under control, and to promote it.1 For example, turned art objects were charged with symbolism in the Kunst- and Wunderkammer context: they indicated the reigning prince’s ability to shape society, like raw material on a lathe, into a well-proportioned configuration.2 Exotic products, by contrast, usually alluded to a prince’s colonial achievements or ambition, referring vaguely to unsophisticated, remote lands as opposed to “civilized” Europe. Only rarely did such exotica depict the actual activities of colonizers in a non-European sphere.3

All the more remarkable, therefore, is a hitherto unknown coconut cup with reliefs (fig. 1, fig. 2, fig. 6, and fig. 9) illustrating the concepts of “savagery” and “civilization” in Dutch Brazil in the mid-seventeenth century. Although typical of Kunstkammer objects in many ways, the cup is exceptional, if not unique, because of its political iconography. As early as the Middle Ages, coconuts were prized as valuable natural commodities possessing therapeutic and apotropaic powers; hence they were usually worked into drinking vessels with costly mounts.4 Carvings on the bowls of such vessels occasionally evoked biblical stories such as “The Drunkenness of Noah” and “Lot and His Daughters,” warning drinkers of the consequences of excessive consumption of wine.5 On the other hand, there are representations, albeit rare ones, reflecting the exotic qualities of the material itself. As far as I know, only six carved coconut cups survive with depictions of indigenous peoples of South America and allusions to the activities of Dutch colonists in the Americas: the most famous of the six came from the Kunstkammer established by the Electors of Saxony and is now in the Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vault) in Dresden (inv. no. IV 325). Then, in addition to the cup under discussion here, there is a cup once owned by Ferdinand Albrecht I of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, which is now in the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Braunschweig (inv. no. Hol 99). The others are in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich (inv. no. R 5338), the Historisk Museum (inv. no. B 513) in Bergen, Norway, and a private collection.6

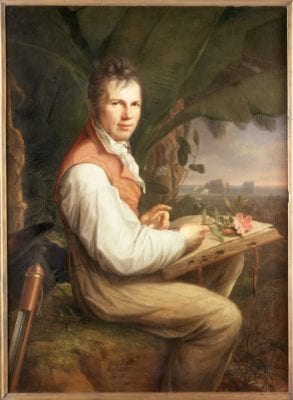

The present work of art adds a crucial study object to this small group of coconut cups with Brazilian representations. Moreover, the provenance of this vessel provides insights into later responses to mid-seventeenth-century representations of Brazil. The cup was owned by Alexander von Humboldt, the Berlin naturalist and explorer who made such a vital contribution to the scientific exploration of South America in the early nineteenth century. In the following essay, the iconography of Humboldt’s covered cup will be examined with respect to the cup’s function in Johan Maurits’s Kunst- and Wunderkammer so that its history can be used to reconstruct the changing interplay of power, art, and science in the context of the early modern world and modern ideas about collecting.

“Savagery” and “Civilization” in Dutch Brazil: The Iconography of the Humboldt Cup

The Humboldt coconut cup (fig. 1) consists of a carved nut mounted on a tall foot and held in place by three silver braces. Although the silver mount is fairly simple in appearance and bears no marks, the bowl of the cup is elaborately decorated with three relief fields.

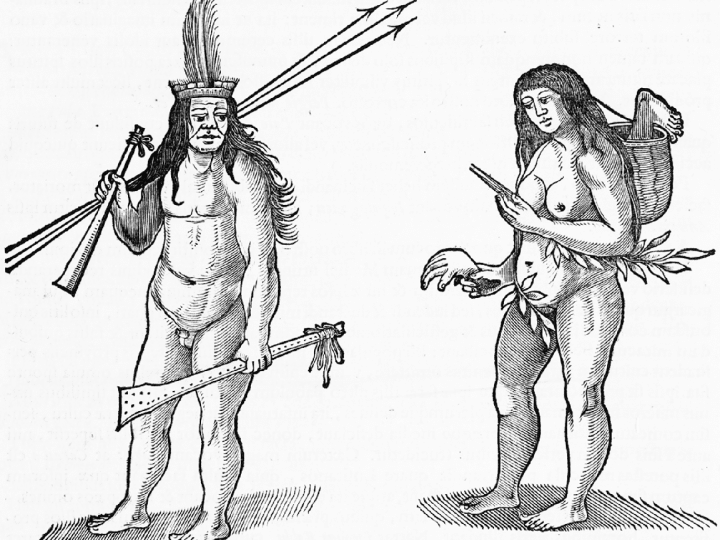

The first scene (fig. 2) features “savage” indigenous peoples: a woman with a basket bound to her forehead and a naked warrior. The warrior carries a club in his hand and two spears over his shoulder. He is unmistakably characterized as an Indian by his feather headdress, which was worn by the Tupinambá and other peoples of the Amazon Basin and from the sixteenth century on was regarded as an identifying attribute of American Indians in general.7 The Tupinambá lived on the coast of Brazil and were notorious in Europe for their practice of cannibalism. The Frankfurt publisher Theodor de Bry contributed decisively to the reputation of these indigenous peoples as cannibals. The third volume of his widely circulated Grands Voyages (1592) contains eyewitness accounts furnished by Hans Staden and Jean de Léry of French attempts at establishing a colony in Brazil (1548–58).8 From then on the Brazilian Indians were regarded as prime examples of the “savage native.” Confirming the prejudices of post-Renaissance Europeans, the woman accompanying the warrior on the Humboldt cup is characterized as a cannibal: in her left hand she holds a severed hand and a human foot protrudes out of the basket bound to her forehead (fig. 2).

Indeed, the female cannibal with a severed foot in her basket became a popular motif in the latter half of the seventeenth century. The motif was introduced by the Dutch painter Albert Eckhout, who stayed in what is now Brazilian territory from 1637 to 1644 to document, along with other artists and scholars, the achievements of Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen in Dutch Brazil. Eckhout based his figures on members of the Tapuya (actually Tarairiu) tribe,9 who inhabited the coastal hinterland of eastern Brazil. Upon returning to Europe, Eckhout painted from oil sketches (now lost) the large-format pictures, with life-size figures, presented by Johan Maurits in 1654 to King Frederick III of Denmark to decorate the Copenhagen Kunstkammer (fig. 3).10 The paintings might seem to view the indigenous peoples of Brazil objectively. However, the painter exploited stereotypes that had become commonplace in European painting. Since the sixteenth century, the severed limbs of victims had figured as principal attributes of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.11 The woman carrying a severed foot undoubtedly represents a nod to the previously mentioned series of engravings published by De Bry, who had stigmatized the Tupinambá, the tribe whose territory adjoined that of the Tapuya, as cannibals. It was, in fact, the unlikely combination of studied allegory and empirical observation that made Eckhout’s paintings so successful.

Eckhout’s representations of ethnographic types were especially interesting to the artists and naturalists who had accompanied Johan Maurits to Brazil. The young Dresden painter Zacharias Wagener copied Eckhout’s oil sketches in his Thierbuch, in which he wrote an account of his travels.12 Of paramount importance for viewer response to Eckhout’s pictures, however, were the woodcuts included in Historia rerum naturalium Brasiliae by the German naturalist Georg Markgraf, another member of Johan Maurits’s entourage in Brazil. The woman carrying a severed foot and her companion recur as an illustration to Johannes de Laet’s epilogue for the Historia (fig. 4)13 in a woodcut also copied from Eckhout’s oil sketches. In the years that followed, this woodcut served several naturalists and artists in turn as the prototype for illustrations accompanying accounts of their own travels. Among these was the traveler Caspar Schmalkalden, who had encountered Georg Markgraf in Brazil and would later plagiarize the naturalist’s studies of Brazilian natural history. In 1652, after he had returned from a decade of travels through Asia, Africa, and South America in the service of the Dutch East and West India Companies, Schmalkalden was hired as chancellery clerk at the Gotha court because of his experiences and knowledge. There he acquired precious exotica for the Kunstkammer owned by Prince Ernst and wrote a compendious account of his travels. In his treatment of the indigenous peoples of Brazil, he not only took over De Laet’s text verbatim but also copied the illustrations from Markgraf’s Historia.14

Jan van Kessel the Elder’s 1666 painting America (fig. 5) indicates the popularity of Eckhout’s cannibal woman with artists. Whereas van Kessel depicted in the foreground various peoples, artifacts, and animals as representative of the New World, in the background he chose to include the savage woman (complete with severed limb protruding from her basket) and her warrior companion as statues standing under arcades. No wonder, then, that the same cannibal woman recurs, only slightly altered, on one of the six coconut cups mentioned above.15 While Albert Eckhout’s painting was the ultimate source for that formulaic representation, the woodcut published in 1648 in the Markgraf work on Brazil was the prototype for all the above-mentioned writings, paintings, and the cup presented here. Eckhout had depicted the woman with short hair; on the Humboldt cup and in the other representations, including van Kessel’s, she has long hair – just as she has in the woodcut.

The second scene carved on the Humboldt cup (fig. 6) was also inspired by Eckhout’s paintings, although it does not quote them directly. An Indian with a bow and arrows is accompanied by a woman carrying a basket full of fruit and flowers on her head. The two figures on the cup are dressed – a clear indication that they are no longer regarded as cannibals but rather as “civilized” natives working on a plantation. In his painting cycle, Eckhout had depicted various inhabitants of Brazil to illustrate European influence on the indigenous peoples of South America and the various ethnic groups living in the Dutch colony. He also made a point of using clothing to show each figure’s degree of civilization.16 A Mamelucos woman wearing a long cotton dress (though she is barefoot)17 was, for instance, among the most “Europeanized” natives. Eckhout’s dressing of his Mamelucos is echoed on the coconut cup by the figure of the woman, who is also depicted on the cup in the Dresden Green Vault (fig. 7).18 Here, too, the representation derives from a woodcut after Eckhout: the man with a bow and arrows is a slightly altered version of the corresponding figure in Markgraf’s natural history (fig. 8).

The third relief on the Humboldt cup (fig. 9) depicts a scene by the sea: a sumptuously dressed European lady hands a fish to a native. A paddle and fishing line unmistakably characterize the Indian as a fisherman. He appears in a slightly different pose on the carved coconut in the Historisk Museum in Bergen (fig. 10).19 An inscription on the cup identifies the figure as a fisherman from the Tapuya tribe. A small round fortified tower is discernible behind the fisherman on the cup in Bergen and the Humboldt cup discussed here. A similar fort is depicted on the fragmentary carved coconut cup in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum. On this piece, a ship sailing into a harbor is depicted.20 An inscription identifies the harbor as Recife de Pernambucco, one of the most important Dutch outposts on the Brazilian coast. The small port city was fortified in the 1630s when the Dutch had to fight the Portuguese for supremacy in Brazil. Hence the fortified tower in the sea stands as pars pro toto for the place where the two cultures met: it was at Pernambucco that the Dutch first came into contact with the indigenous peoples of Brazil. The Humboldt cup depicts that encounter and the consequences it had for the New World: the lady, recognizable from her dress as a European, can be interpreted as a personification of Europe and the fish she hands the Indian as the symbol of Christ. The scene can, therefore, be read as follows: the savage has been converted to Christianity through the intercession of Europe. He becomes a fisherman who, like the Apostle Peter, contributes to the spread of Christianity among his fellows. No longer a cannibal like the natives in the first relief panel, he has been changed into a “good savage,” like the scantily clad plantation workers in the second relief panel, above whom, moreover, a dove hovers! One might wonder, however, which Christian doctrine is meant here. The sun rising full of promise over the land of these pagans first touches the little fort in the sea, possibly an allusion to the Lutheran hymn A Mighty Fortress Is Our God. More generally, the representation might be intended to portray Protestant doctrine as the true faith, a likelihood reinforced by the historical context for the Humboldt cup.

By the 1630s and ’40s, Brazil had become a battle ground fought over by two colonial powers: the Dutch and the Portuguese. The Dutch West India Company, with the support of Johan Maurits, was attempting to drive the Catholic Portuguese from Brazil and thus increase the Dutch share in the sugar trade. Indigenous peoples were involved in the struggle on both sides: although numerous Tupinambá worked on Dutch plantations, Jesuit influence had made the tribe well-disposed toward the Portuguese and ensured their allegiance as allies. For military purposes, Johan Maurits, governor-general of Dutch Brazil since 1637, relied mainly on the Tapuya tribe, which had been trying to shake off the Portuguese yoke.21 Nevertheless, despite their alliance with the Dutch, the Tapuya were, like the Tupinambá before them, regarded as savages of evil character and uncouth habits. In his eulogy honoring Johan Maurits, Caspar Barlaeus described the “Tapuyer” as barbarians feared by the other Indian tribes and the Portuguese alike.22 The reliefs on the Humboldt cup, on the other hand, suggest that the Dutch were capable of transforming aboriginals into harmless Christian plantation hands. This points to the political character of the carvings on the cup: they illustrate the supremacy of the Protestant powers (the Dutch States General in the first instance) in achieving the acculturation of the “savages” and “civilizing” the New World.

Power, Art, and Science: Johan Maurits’s “Brasiliana” Collection

The unique iconography of the reliefs on the bowl of the Humboldt cup indicates they were created by an artist working in the sphere of influence of Johan Maurits. Artists (Albert Eckhout and Frans Post) and scientists (Willem Piso and Georg Markgraf) had accompanied the governor-general to Brazil to investigate the character of the country and its inhabitants and describe the Brazilian flora and fauna, thus underpinning and legitimizing the governor-general’s colonial ambitions.23 The artists in his retinue may have included carvers as well as painters.24 Building on this possibility, Rolf Fritz, an expert in coconut carvings, has concluded that the few known cups with Brazilian scenes were made on site in the Dutch colony. But this seems unlikely, because, as shown above, the reliefs (on the Humboldt cup as well as on the cups in Braunschweig, Dresden, and Bergen) were based on woodcuts that were not published in Holland until 1648, four years after Johan Maurits returned to Europe. The coconut cup from the Historisk Museum in Bergen (fig. 10) bears the date 1653, which definitely indicates its execution in Holland.25 Eckhout’s ethnographic type-portraits were also long believed to have been produced in Brazil,26 but, again, recent research has demonstrated that they were painted in Holland.27 Why then were the words fe[cit] bresil (made in Brazil) added at the bottom of Eckhout’s canvases? Johan Maurits never tired of emphasizing that all the exotic artifacts in his collection had been made in Brazil,28 apparently wishing to emphasize the scientific nature of his collection. The native origin of the objects verified the authenticity of what had been seen and depicted.29 Johan Maurits wanted his collection of artifacts to be viewed as an authentic microcosm of the overseas territory that had been explored, charted, and classified – in a word, governed – by Europeans, in this case by Johan Maurits himself.

It should be remembered, however, that Johan Maurits was not a sovereign ruler. As governor-general of Dutch Brazil and an employee of the Dutch West India Company (WIC), he was chiefly obliged to act in an economic and military capacity. He was expected to help drive the Portuguese from the territory in order to secure and increase the WIC’s share of the sugar and slave trade. Although he was merely a colonial administrator, Johan Maurits assumed in Brazil the posture of a European ruler. His residence at the courts of his brother-in-law, Moritz of Hesse-Kassel, and his uncle, Stadtholder Frederik Hendrik, prince of Nassau and count of Orange, had thoroughly familiarized Johan Maurits with princely representational strategies.30 Like his royal relatives, Johan Maurits defined “his” territory on the basis of surveying, cartography, astronomy, and natural history. He also flaunted his authority by building palaces, founding cities, and amassing collections in emulation of the European sovereigns. This territorial claim implied a court not actually present in Brazil. Apart from a modest retinue in Mauritsstad,31 the only “subjects” Johan Maurits could command were Portuguese colonists, Dutch employees of the WIC, Jewish merchants, slaves, and indigenous peoples. Hence he was forced from the outset to construct his self-display around portable artifacts that were scientific in nature. Because these were regarded in Europe as coveted objects for transmitting and demonstrating knowledge, he felt justified in introducing them into the exchange of diplomatic gifts between courts. While most of these gifts were treatises, such as Markgraf’s Historia rerum naturalium Brasiliae, paintings, tapestries, and other art works, such as the Humboldt cup, played a considerable role in Johan Maurits’s cultivation of his identity as “ruler of Brazil.” They transmitted the idealized image of a multicultural society governed by a liberal Protestant overlord who had “civilized” it by peaceful means. The brutal reality of a tough mercantile plantation society rife with armed conflict and segregation was passed over in silence.32

In the light of history, the Dutch attempts at colonizing Brazil between 1630 and 1654 must be evaluated as a failure. Nonetheless, Johan Maurits did succeed in instilling in the collective memory of both Europe and South America the notion of his rule as instrumental in creating a flourishing society in Brazil. This success was not based on any actual military or economic achievements but rather on his deliberate dissemination of knowledge about the areas he had colonized. His passion for collecting played a crucial role here: his unique collection of Brazilian artifacts and natural history specimens was a vehicle suitable for burnishing his public image in that it publicly justified as “civilizing” his decidedly unpeaceful intervention in the New World.

According to Caspar Barlaeus, Johan Maurits had established a “museum” at Boa Vista, his summer residence. Unlike the traditional Kunst- and Wunderkammer, the Boa Vista museum comprised only naturalia and artificialia related to South America and Africa (that is, to the regions actively colonized by Johan Maurits). In addition, live animals and plants could be admired in the palace menagerie and gardens.33 On his return from South America, Johan Maurits at first displayed his “Brasiliana” in his residence in The Hague. According to Barlaeus’s Rerum per Octennium in Brasiliae…historia (1659), Johan Maurits soon afterward donated numerous taxidermy specimens to Leiden University, for the benefit of the anatomical theater there.34 This is one of the first instances of the clever exploitation of his collection’s claim to be scientifically important, a claim that soon became the basis for a self-aggrandizing propaganda strategy. In this regard, he gave choice items to Friedrich Wilhelm I of Brandenburg, Frederick III of Denmark, and Louis XIV of France. Such items, taxidermy specimens of rare fauna, paintings, weapons, and articles of indigenous apparel, were so highly prized that the recipients immediately added them to their collections. Once displayed, they would be discussed by an aristocratic and scholarly public while simultaneously promoting the image of Johan Maurits, “the Brazilian,” as a liberal colonial overlord. The extent of his largesse is evidenced by the fact that his bequest to Frederick III in 1654 consisted of twenty-six Eckhout paintings as well as Brazilian ethnographica.

The Eckhout group originally included a (lost) portrait of Johan Maurits characterizing him as a Brazilian ruler,35 while a gift he made to Friedrich Wilhelm I of Brandenburg in 1652 conveyed the same political message via its inclusion of art works devoted to scientific subjects. This is especially true of the 2,500 Eckhout drawings, watercolors, and oil studies of flora and fauna that would later be bound as the Theatri rerum naturalium Brasiliae.36

Scholars have often pointed out that Johan Maurits viewed such gifts mainly as pretexts for exacting favors.37 Indeed, he expected to receive financial advantages from such diplomatic gifts. In 1652, he received quite a large sum of money from Friedrich Wilhelm, which enabled him to purchase Freudenberg Castle near Cleve. When he dispatched Brazilian artifacts, paintings, and prepared fauna specimens to Louis XIV in 1679, Johan Maurits unabashedly outlined his expectations in a letter to Simon Arnauld, seigneur (later marquis) de Pomponne, the French secretary of state for foreign affairs: he asked for money instead of diamonds in exchange.38 It is equally clear that Johan Maurits secured the favor of important rulers with his diplomatic presents. In 1652, the Holy Roman Emperor raised him to the status of Prince of the Empire, probably with the intercession of the Elector of Brandenburg, Friedrich Wilhelm, to whom Johan Maurits had made gifts that same year. At the same time, he was made a member of the Order of St. John. His receipt of the Order of the Elephant in Denmark had little to do with presents to the Danish king, however, for he had been awarded that decoration several years before.39

The material gains that resulted from currying favor in high places were no doubt welcome, but such gains were not the paramount reason for Johan Maurits’s policy of giving diplomatic gifts. Participating in the exchange of gifts between courts was significant in itself for it allowed Johan Maurits to position himself as an influential member of the European company of princes.40 Even more important were the propagandistic aims he pursued, as evidenced not only in the iconography of the gifts themselves but also through their echo in tapestries. Even while Eckhout’s ethnographic type-portraits were being produced in oil, Johan Maurits intended that at least some of them be reproduced in this other medium. When Stadtholder Willem Frederik of Nassau-Dietz visited the painter at Jacob van Campen’s workshop in 1647, he saw “the paintings that Count Maurits had made of all sorts of things from the West Indies, to make tapestries from them.”41 Later, after Johan Maurits had given away most of those pictures, he continued to suggest that Eckhout’s paintings were eminently suitable for reproduction in tapestries. He also twice commissioned the Delft tapestry maker Maximiliaan van der Gucht to make a series (now lost) after the Eckhout paintings he had given to Friedrich Wilhelm, one set being for the Prussian ruler and the second for himself. When Johan Maurits sent gifts to Copenhagen in 1654, he urged Frederick III in a letter – albeit in vain – to “have [the pictures] copied into another medium.”42 He was more successful in convincing Louis XIV, who had tapestries woven after eight of the Eckhout paintings sent to him in 1679.43 It should be borne in mind that since the Middle Ages tapestries had been regarded as precious luxury articles, taken from royal residence to residence as portable media suitable for displaying princely grandeur. Johan Maurits was sufficiently versed in court culture to desire the wider circulation of his Brazilian pictures in the form of tapestries. Nonetheless, he failed to realize that Eckhout’s motifs underwent a semantic shift with the transposition to a different medium and change of owner. Louis XIV subsequently used the “Indian” tapestry series made after Eckhout’s cartoons as his own diplomatic gift, with the result that the tapestries no longer represented Johan Maurits’s “civilizing” achievements in Dutch Brazil but rather underpinned the Sun King’s personal claims to an overseas sphere of influence. He, too, possessed colonies in the New World and in this way he, like Johan Maurits, promoted an imaginary annexation of foreign territory.44

The items from his Brazilian collection that Johan Maurits sent to Copenhagen, Berlin, and Paris all underwent the same semantic shift: by virtue of their integration into different collection contexts, they lost their symbolic load as testimony to his “civilizing” activities in Brazil. This happened to the exotica in many Kunst- and Wunderkammers as they were dispersed: they were subjected to a process of defamiliarization and appropriation, and, once decontextualized, were given new meanings, ultimately transmitting a uniform and generalized image of faraway lands according to European notions.45 Thus as soon as Johan Maurits handed them on, Eckhout’s paintings, the coconuts carved with Brazilian scenes, and the other “Brasiliana” were downgraded to mere “Indian” curiosities of unspecified origin. In a collection belonging to anyone other than the original owner, the reference to Dutch Brazil and its governor-general got lost. A prime example of this process is the Braunschweig coconut cup, which came from the Kunstkammer of Duke Ferdinand Albrecht of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. A paper label bearing the following inscription is glued to the inside of the cup bowl: “Fruits called ‘cocus,’ worked / by savages / so-called / cannibals or cabus / in their language.”46 This label indicates that the steward in charge of the Kunstkammer and surely also its owner were primarily interested in the exotic fruit shell and the representation of savage cannibals traditionally associated with the Americas. In the case of the cup once in the collection of the Elector of Saxony and now in the Dresden Green Vault, the carvings were still known to refer to Brazil as late as 1732, when it was described in the inventory of Dresden Kunstkammer as “an Indian nut, with a silver foot and lid, with gilt decoration, Brazilian pictures, trees and other plants to be seen carved on the nut.”47 The precision of this statement may result from the fact that Eckhout was employed at the Dresden court as a painter for eleven years (he may even have brought with him the cup that later found its way into the Kunstkammer).48 Here, too, the iconographic reference to Johan Maurits’s “civilizing” achievements was rapidly obscured: soon the Dresden coconut cup merely reflected the general influence of Europe in the New World. Like that of all the collector’s items amassed by the former governor-general and dispatched to foreign courts: the cup’s iconography was neutralized, leaving nothing but an exoticism largely bereft of meaning. Scholars, of course, still regarded these objects as conveyors of knowledge that provided a truthful image of the remote lands in which they had (presumably) been made. This circumstance is exemplified by the batch of drawings Johan Maurits had dispatched to Berlin: this treasure trove was rearranged in the latter half of the seventeenth century, subjected to scholarly research, and integrated into the newly established electoral library with the aim of enabling scholars at the Berlin court to study the natural history of Brazil.49 Thus, though the relationship between Johan Maurits’s “Brasiliana” and his colonial power was blurred, the link between art and science continued to be upheld.

Alexander von Humboldt: Art and Science ca. 1800

The Humboldt cup was probably displayed in the seventeenth-century Kunst- and Wunderkammer of a distinguished owner. Perhaps it was numbered among the objects – “made with great artifice” (künstlich) – that went to Berlin as gifts to Friedrich Wilhelm I from Johan Maurits’s collection. If so, because it is not mentioned in the list of objects dispatched in 1652, the cup is likely to have been moved from Johan Maurits’s residence in Sonnenburg (Słońsk) to the Berlin Kunstkammer as part of a later gift in 1676.50 This conjecture cannot be verified. It is certain, however, that the mounted nut was in the possession of the Berlin scholar and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt by about 1800 (fig. 11). He later gave it to his friend Reinhardt von Haeften (1772–1803), in whose family the art object remained for over two centuries.

Humboldt and von Haeften became acquainted in Bayreuth, when von Haeften was stationed there as a Prussian lieutenant of infantry and Humboldt was a Prussian surveyor-general of mines.51 From the winter of 1793 on, Humboldt and von Haeften shared lodgings and traveled together several times, once on a study trip of four months to the Tyrol as well as to northern Italy in the summer and autumn of 1795.52 The two men are said to have been ill-fated lovers.53 At any rate, Humboldt was still living with von Haeften and his wife in 1797.54 Humboldt had originally planned to take von Haeften with him to America.55 In 1799 he set out for five years of travel in South America – but without his dear friend, who by this time was suffering from ill health (von Haeften would die in 1803). Before von Haeften died, Humboldt gave him several articles of silver and two coconut cups as souvenirs, including the object discussed here.56 The cup remained in the possession of the von Haeften family for centuries, greatly treasured, often discussed as a gift from the great Prussian naturalist, and proudly displayed. Family tradition has it that the silver objects Humboldt gave to von Haeften came from overseas. This was not true of the coconut cup, of course, which, as pointed out above, was executed in the Netherlands in the mid-seventeenth century. Humboldt must have acquired it in Europe, perhaps in Berlin, and given it to von Haeften before 1799. Even before he left for South America, Humboldt is known to have been interested in several art works of an exotic nature.

During his scientific career, Humboldt often turned to works of art to study natural phenomena more closely. He viewed painting, for instance, as a suitable instrument for scientific studies because painters were able to omit nonessentials in order to concentrate on the characteristics of a landscape. And that is exactly what mattered to Humboldt in his natural history studies: objectively examining natural phenomena and the laws governing them.57 Before 1799 all that Humboldt knew of Brazil was what he had seen in greenhouses or in paintings. The representations of indigenous South Americans on the carved nut would have attracted his attention, particularly before he had traveled to South America.

In Humboldt’s Kosmos, we read about his interest in pictures representing the indigenous peoples of South America. There he reports that he had seen Eckhout’s “most excellent large oil pictures” (including the ethnographic type-portraits, which indirectly inspired the reliefs on the coconut cup) at Frederiksborg Palace in Copenhagen in 1847.58 It is not entirely surprising that Humboldt should have studied the paintings, which had by then been entirely forgotten, in Copenhagen or that he should have rediscovered their scientific value for posterity. He was, after all, familiar with Eckhout’s ethnic typology from the carved coconut cup he had owned as a young man. Humboldt, of course, evaluated the Eckhout paintings and the coconut cup carvings without any reservations about their being truthful representations, seeing them indeed as good “examples of physiognomic representation from Nature.”59 This observation makes Humboldt the first to view Eckhout’s pictures as accurate ethnographic portraits. By the time the paintings were incorporated in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer in 1654, the propagandistic message they originally conveyed had receded into the background, and by the early nineteenth century, it had disappeared altogether from public awareness. Both the paintings and the coconut cup had become, in Humboldt’s eyes, verifiably objective testimonials to what had been witnessed in Brazil. No longer representing colonial power, they were now solely objects of interest to art and science.

Translated by Joan Clough