Early users of medieval books of hours and prayer books left signs of their reading in the form of fingerprints in the margins. The darkness of their fingerprints correlates to the intensity of their use and handling. A densitometer — a machine that measures the darkness of a reflecting surface — can reveal which texts a reader favored. This article introduces a new technique, densitometry, to measure a reader’s response to various texts in a prayer book.

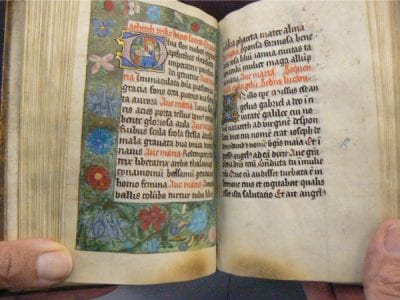

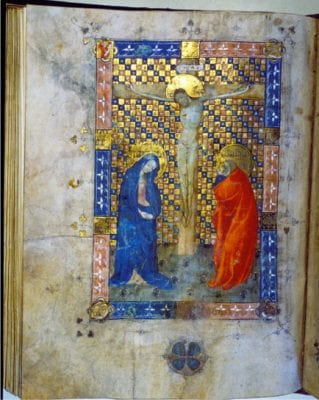

Although it is often difficult to study the habits, private rituals, and emotional states of people who lived in the medieval past, medieval manuscripts carry signs of use and wear on their very surfaces that provide records of some of these elusive phenomena. One of the most obvious ways in which a category of manuscripts—missals—carries signs of use is the damage often found in the opening of the canon of the mass. A priest would repeatedly kiss the canon page of his missal, depositing secretions from his lips, nose, and forehead onto the page. In the Missal of the Haarlem Linen Weavers’ Guild, made in Utrecht in the first decade of the fifteenth century, the illuminators provided an osculation plaque at the bottom of the full-page miniature depicting the Crucifixion. This plaque is designed to bear the wear and tear of the priest’s repeated kisses, for illuminators realized that priests would damage their paintings if they could not deflect the lips elsewhere (fig. 1). The priest in Haarlem who used this missal kissed the osculation plaque some of the time, but his lips also crept upward, onto the frame of the miniature, onto the ground below the cross, up the shaft of the cross, occasionally kissing the feet of Christ.

Taking as my premise the idea that missals reveal habits of wear and use, in this article I bring together other manuscripts—especially prayer books—that have been rubbed and handled. These examples reveal how medieval people interacted with their books and reveal something of their habits and expectations, and ultimately, an aspect of medieval readers’ emotional lives. I first consider how images were abraded through devotional kissing and rubbing that was directed at a particular image, or even a particular area of an image, or occasionally directed at a text. I then consider how material was often inadvertently added to manuscripts through handling. Users employed thread and glue to affix devotional objects to their books, and fingerprints and dirt darkened the page as the user ground it into the fibers of the vellum. The more intensely a reader used a given section of the book, the more intensely discolored those folios are. My contribution to this discussion of reader response is to quantify this wear using a densitometer, an apparatus that measures the darkness of a reflecting surface. The densitometer has allowed me to objectively measure the wear, which is positively correlated to the darkening of the vellum (or paper) manuscript support. The results reveal how a given reader handled his book, which sections of a book he handled, and which he ignored. These are discussed as a series of case studies below.

Quantifying Fingerprints

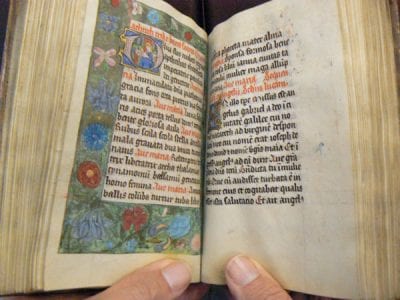

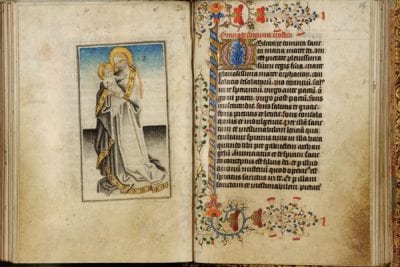

Discoloration due to wear is identifiable as such. A recto leaf from a prayer book made in the eastern Netherlands (Luik, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Ms. 2091B, fol. 14r) shows that, in this case at least, most of this user-deposited dirt appears in the lower outer corner of each folio (fig. 2). It is very easy to distinguish the discoloration of wear from the discoloration caused by water damage, which likewise causes darkening. Water damage appears, for example, in a manuscript made in Delft and preserved in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague (Ms. 135 E 12; fig. 3). Water damage always carries a high-water mark on its leading edge and can easily be identified. The discoloration of vellum caused by water damage is not relevant to the current study.

As far as I know, discoloration due to wear in manuscripts has never before been considered as a topic of inquiry, besides casual comments about a certain book being “worn” or “heavily handled.” Studying the dirt, smudges, and signs of wear in a manuscript constitutes a form of forensic analysis that can reconstruct readers’ habits. The fact that readers regularly picked up a book and read it, as occurred with devotional books, implies that the book was regularly held in the same way.1 This means that repeated handling resulted in a cumulative build-up of fingerprints over the same area of the vellum. Under magnification, the vellum looks like a rug that has trapped dirt and grime in its fibers (fig. 4 and fig. 5). As readers read the text and looked at the images, this normal but intensive handling left fingerprints on the page, and these marks, although made inadvertently, are nevertheless instructive. Significantly, the signs of wear are not usually distributed evenly throughout the book. The densitometer confirms what I had suspected: that readers often concentrated their reading on particular texts, thereby darkening the corresponding folios. The fact that the darkened folios often correspond to the text divisions confirms the validity of the technique.

We can add densitometrical analysis to the manuscript scholar’s toolbox of forensic techniques, which also includes the use of ultraviolet (UV) light or other techniques to help to disclose texts that have been scratched out. In the last two decades, infrared reflectography has been used to reveal the underdrawing beneath a painted surface. This technique has been used with great success on panel paintings and with mixed success on manuscripts. Simple, low-tech codicological analysis, including the creation of structural diagrams of the book’s construction and layout, also constitutes a forensic technique, which reveals certain workshop practices and can help to identify leaves that have been added or cut out. All of these techniques apply objective criteria to the physical book and can add to our understanding of aspects of the book’s history, production, ownership, and handling.

It is not unusual to encounter a manuscript that has one text which has received far more wear than the other texts. A Southern Netherlandish book of hours, probably made for the Augustinian canoness depicted kneeling at an altar on fol. 153r (fig. 6), shows that she used the manuscript unevenly.2 The manuscript, upon first inspection, appears quite clean and unhandled. But fol. 67r, containing a rubricated indulgence, has a small amount of discoloration in the lower margin fig. 7). The following opening (fig. 8) has more intensive discoloration, indicating the reader’s even longer engagement with this opening, which contains a prayer invoking the “Seventy-two Names of the Virgin.”3 The prayer, which was considered by some to be apotropaic (that is, it held the power to avert evil influences), finishes on the next opening (fig. 9), which is slightly discolored, indicating a proportionally smaller engagement with this part of the text. These are the only three discolored folios in the manuscript, strongly suggesting that the book’s user had a sustained relationship with them, through which she cumulatively deposited grime from her fingers.

It is clear that users did not read these kinds of books from beginning to end. Instead, they appear to have selected texts relevant to the time of day (the various canonical hours), the time of the liturgical year (say, Advent), or an important event, such as the anniversary of the death of a loved one. Sometimes evidence of the user’s handling appears on the outer edge, a few centimeters from the bottom, as in a book of hours made by the Sisters of St. Agnes in Delft (Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I, Ms. 21696, 116v-117r; fig. 10).4 It is possible that the sisters themselves especially esteemed the prayer Obsecro te, which is transcribed on fol. 117r and around which one of the sisters apparently wrote the inscription that identifies the book’s makers.5 Both the Obsecro te and the litany have darkened borders that index heavy wear. The other folios are not emphatically discolored along the outer edge, indicating that the reader handled the other pages less frequently. Unfortunately, most of the dirt on the other pages was probably trimmed off when the manuscript was rebound. In fact, manuscripts were often rebound because they were dirty, the process providing an opportunity to trim the soiled, handled edges away.

While most readers handled an area of the page near the outer corner, not everyone did. Apparently, the habit of reading a particular prayer book was also coupled with a habit of holding the manuscript in a particular way each time. The owner of the Brussels prayer book mentioned above did not hold the book at the outer corners, as most owners of octavo-sized manuscripts did; instead, she held it open near the gutter (fig. 11 and fig. 12).6

The patterns of wear in these examples show that their owners favored certain texts and images to the exclusion of others. As I was considering how to interpret this fact, I wondered whether it was possible to quantify such patterns of use. The rest of this article is dedicated to answering that question by using a densitometer.

The Densitometer: Case Studies

I. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 74 G 35

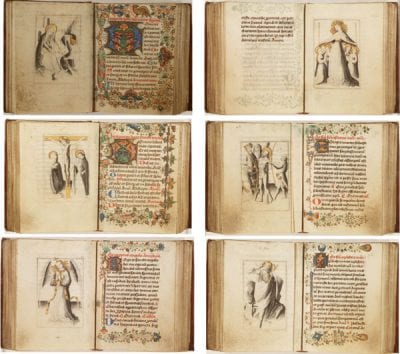

A book of hours made in Delft between ca. 1460 and ca. 1480 also reveals uneven patterns of wear across its various texts. Comparing six openings from the manuscript immediately reveals that some of the texts were more handled than others (fig. 13). The Hours of the Virgin, the Hours of the Cross, and the suffrage addressed to Saint Sebastian are quite worn. (A suffrage consists of a prayer, versicle, and response and usually implores a saint to intercede on the votary’s behalf.) The suffrage to the owner’s personal angel, prefaced by a full-page grisaille depicting an angel, and the one to Saint Christopher are slightly less worn, while the suffrage to Saint Ursula and the eleven thousand virgins is even less worn. I wanted to find a way to turn the terms “more than” and “less than” into quantifiable terms that would describe these varying degrees of use with more specificity. Ultimately, I wanted to find an objective way to encapsulate these reader’s marks.

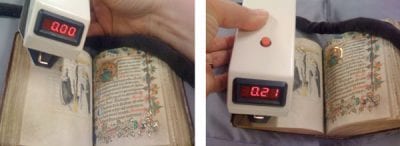

The densitometer is an instrument that measures the darkness of a reflecting surface in a noninvasive way.7 For this study I used two different densitometers, one (a Heiland electronic Wetzlar, model TRD 2) for the manuscripts in The Hague, the other (an X-Rite, model 418) for all other manuscripts. Both have nonabrasive contact surfaces. They work by shining a small light onto a localized patch (incident light), then measuring how much of that light is reflected back onto a photoelectric cell in the densitometer. What has not been reflected has been absorbed. The amount of light absorbed is an index of the darkness of the patch.

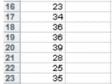

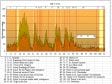

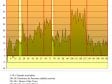

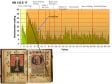

I also accounted for the varying darkness of the vellum. To use the Wetzlar, I zero the scale on a part of the vellum that has not been intensively handled, then take a reading from the same page, at the epicenter of the dirt, and record the result (fig. 14). The X-Rite, on the other hand, does not have a zeroing feature, and I therefore take a reading from the epicenter of the dirt and subtract a reading from a clean part of the same page, which in effect, achieves the same result as zeroing the scale (see fig. 15). In this way, I can account for the darkness of the vellum and subtract it from the value of the dirt.8 Experiments revealed that the darkness of the left and right sides of an opening have readings within five percent of one another; I therefore took only a reading from the recto side of each opening and plotted these numbers in a spreadsheet, where each row number corresponds to a folio number (fig. 16). Arrayed in this way, the data easily generated a graph of usage (fig. 17). The densitometry values show the relative degree of handling of the various folios and sections of each manuscript.9

The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 74 G 35—like all books of hours—comprises multiple texts. Readers did not read their books from cover to cover, but rather read individual texts. Books of hours were not foliated or paginated, and readers found their desired text with the help of the decoration, which marks the beginnings of new texts. In Ms. 74 G 35 full-page single-leaf grisaille images, inserted before the major textual incipits, helped the reader to find the texts. The densitometry graph for this manuscript reveals that the various texts in the book—the calendar, Hours of the Virgin, Hours of the Cross, the Seven Penitential Psalms, suffrages, and the Vigil for the Dead—received different amounts of wear and attention. The end of the manuscript, highlighted in the graph in yellow, was added later, and I will discuss that part below.

The graph reveals that the reader spent the most time with the Hours of the Virgin and considerably less time with the Hours of the Cross, where the total area under the curve is a fraction of that for the Hours of the Virgin. A closer look at the shape of the graph corresponding to the parts of the Hours of the Virgin reveals that the graph drops off considerably at the end, indicating perhaps that the owner often fell asleep before reaching compline, the seventh and last of the canonical hours.

The graph also reveals some sharp dips. The cleanest opening in the manuscript is fol. 58v-59r, not surprisingly, as the verso contains only 2 1/2 lines of text, and the recto is blank (fig. 18). This opening comes at the end of the Hours of the Cross, opposite the blank back of page that contains an image of the Last Judgment. Reading this brief snippet of text occupied hardly any of the votary’s time, and consequently, she left hardly any dirt at this opening.

The densitometer scale jumps back up at the next opening, revealing that the votary had a considerable engagement with the Seven Penitential Psalms (fig. 19). In this manuscript, as in all books of hours, the Penitential Psalms are followed by the litany of the saints. The densitometer spikes at the litany, suggesting that the votary regularly petitioned the saints. The votary reiterated this interest in the saints at the suffrages, which are all quite worn, although the spikes reveal the votary’s special interest in her personal angel and in Saint Sebastian (fig. 20). The darkness at the litany and the darkness at the suffrages help to build a consistent portrait of the reader, who desired personal protection.

Finally, the additions at the end of the manuscript reveal more about the reader’s habits and anxieties. The owner tacked several quires to the end of the book, so that folios 143 onward, shown in yellow on the graph, represent a different campaign of work. Both the miniatures and the style of border decoration differ in this added section, as is visible in the miniature and marginal decoration at the opening for the prayer to the Veronica (fig. 21). What is noteworthy about this added section is that it contains texts for which the reader would earn indulgences. These include the famously indulgenced prayer to the Face of Christ and a prayer beginning Adoro te incruce pendentem, which was said to have been written by Pope Gregory (fig. 22).10 The prayer carried a large indulgence as the rubricated text on fol. 143r advertises. This rubric is not heavily worn. Presumably, the owner read it a few times, knew that it stated that “anyone who reads the following prayer on bent knee will earn an indulgence of 20,014 years and 24 days, as ratified by Pope Calistus III.” At subsequent recitations, the reader just got on with the prayer itself, skipping the introduction. The short prayer is a petition to the arma Christi broken into sections, each section beginning with the syllable of lament, “O!” The following opening (fol. 144v-145r) contains the remaining verses. The version in this manuscript has seven verses headed by seven Os. There were shorter, five-verse versions in circulation that generally carried a smaller indulgence, and longer versions with additional verses that often carried immense indulgences.

The two openings that contain the Adoro te in cruce pendentem, from fol. 143v to fol. 145r, reveal the reader’s penchant for this text. This prayer is heavily worn, creating the largest densitometry spike in the manuscript. Originally there was an image facing the incipit—probably one depicting Pope Gregory having his vision of Christ while performing mass—but as the strong disparity between the amount of wear on the facing folios indicates, someone has cut this out; this missing folio has, quite incongruously, left a pristine fol. 143v facing a heavily thumbed fol. 144r.

What is clean is, of course, as telling as what is dirty. The graph also indicates that the user ignored the prayers that did not have indulgences attached to them.

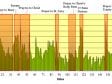

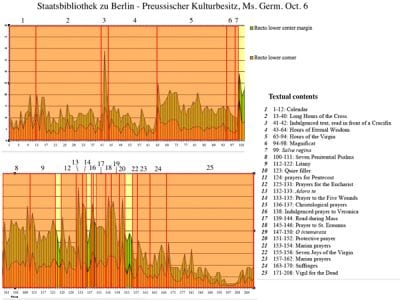

II. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Ms. Germ. Oct. 6

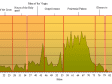

From this manuscript, a book of hours from Delft probably made in the 1470s, I took densitometry readings both from the recto corner and from the center of the lower recto margin, which correspond to the green and red graphs, respectively (fig. 23).11 I had perceived two different areas of grime on the pages and suspected that the darkness might have been caused by two separate readers; however, the two superimposed graphs simply reiterate each other, one at a higher amplitude. This probably indicates that the two areas of darkness emanated from a common source—thus a single reader.

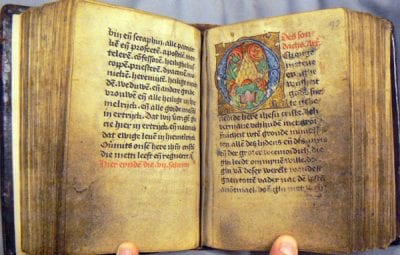

The early owner of this book of hours used many different texts in the manuscript, including the Seven Penitential Psalms and the litany of the saints. He or she was moderately interested in the Long Hours of the Cross (fig. 24) but read the text at the end of that section—an indulgenced prayer to be read in the presence of a crucifix—with much more frequency. The reader was also interested in other indulgenced texts in the manuscript: a prayer to be said in the presence of the Vera Icon, or Holy Face of Christ (fig. 25); the Adoro te in cruce pendentem in the presence of the arma Christi (fig. 26); and a prayer to Saint Erasmus, which was both apotropaic and indulgenced, according to its rubric:

Rubric: Anyone who reads this prayer every Sunday with devotion with contrition in his heart, God shall provision him with everything that is necessary, and he will not die a bad or sudden death, and he will receive the Holy Sacrament and extreme unction, and he will be released from all of his enemies, and he will receive an indulgence of 140 days. Incipit: O, holy and glorious martyr of Christ, St. Erasmus…12

It is difficult to say whether the owner of this book of hours was a layperson or a member of a religious order. The manuscript has a calendar and other features that suggest it may have been made at the Franciscan convent of St. Ursula in Delft. It is reasonable to assume that regardless of the exact identity of the owner, he read the book with the intent of achieving comfort about the state of his soul.

III. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 71 G 53

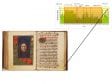

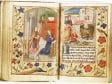

The owner of The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 71 G 53 was not obsessed with indulgences or saints but rather with penance. This manuscript is a prayer book that was probably made for the figure depicted at her prie-dieu (a piece of furniture designed to support someone in a kneeling position), in the garb of an urban woman from the Southern Netherlands around 1505 (fig. 27). She reappears on fol. 79v, wearing a black veil, kneeling in prayer at an altar, accompanied by her guardian angel (fig. 28). She may have been a woman in holy orders. Clues in the calendar and litany help to localize the manuscript and give it an institutional context. The manuscript opens with a calendar for Malines (Mechelen), with feasts in red, which include that of Saint Rombout (July 1), the patron of the largest church in Mechelen. Saint Augustine is listed first among the confessors in the litany, meaning that he has been singled out for special veneration. There is a large section of suffrages to individual saints, and Saint Augustine is among those represented by a small miniature; furthermore, Saint Anna and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary receive a full border, whereas the other saints do not (fig. 29). Given the garb of the woman in the border and the emphasis on saints Augustine and Elizabeth, it is possible that this manuscript was made for one of the sisters who worked at the hospital in Mechelen (gasthuiszusters Augustinessen), where the sisters took the vows of Saint Augustine. Like most late medieval hospitals in the Low Countries, this one was dedicated to Saint Elizabeth, who was said to have ministered to the sick. This same group of sisters created besloten hofjes, that is, reliquaries filled with silk flowers and small devotional objects, complete with wings commissioned from professional painters (fig. 30).13

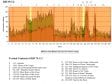

When I first examined this manuscript’s patterns of dirt, I thought I detected the fingerprints of two different users, one at the lower center of each page, the other at the outer edge. The two areas of darkness are especially apparent on some of the text-only folios with no border decoration, such as fol. 58v (fig. 31). Consequently, I took densitometry readings from both areas of darkness in each opening (measuring only the recto sides) and logged them into the spreadsheet (fig. 32). They revealed, however, exactly the same patterns of use, with the one graph reiterating the other but at a higher amplitude, and I concluded that the reader usually held the book at the center of the lower recto, and sometimes held it at the corners.

The text that received the reader’s most sustained attention was the Seven Penitential Psalms, which appears in a privileged place just after the calendar (fig. 33). In contradistinction to the previous example, here the graph drops off at the end of the text, the part that represents the litany of the saints. The owner was consistent in her negligence of the saints, as she similarly ignored the other main text dedicated to saints, the suffrages at the end of the book. Despite the fact that every saint was depicted in a miniature, probably at considerable cost to her, she read these texts infrequently, and they remained quite clean.

Like the owner of the Delft book of hours in the previous example (The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 74 G 35), she revealed a penchant for the prayer Adoro te in cruce pendentem (fig. 34). The edges of this text are strongly discolored. Reciting this prayer would have earned thousands of indulgences for the reader. The other heavily used text in this manuscript was a prayer to the Trinity (fig. 35), which corresponds to a spike in the graph, Late medieval votaries turned to the Trinity for personal protection, and several examples below will demonstrate the depth of this belief.

The graph begins to tell a story about this book owner: she was interested in earning indulgences, although her manuscript afforded her few opportunities to do so. She found comfort in addressing the God of King David but was not too terribly interested in saints or else found other outlets—such as the besloten hofjes—for venerating them.

IV. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 133 D 10

The owner of The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 133 D 10 was also smitten with the Trinity. This manuscript was made in the eastern Netherlands, possibly for a couple whose coats of arms appear on the borders of two of the full-page miniatures (fig. 36 and fig. 37). The coats of arms have not yet been identified. The densitometry data yielded a surprising graph, indicating that a prayer called the Fifteen Pater Nosters—which carried a large indulgence—was heavily handled (fig. 38). The densitometer also revealed a peak at the prayer to the Trinity. The owner’s interest in this theme is confirmed by the inscription, in a late fifteenth-century hand, below the miniature depicting the Trinity (fig. 39).14

One of the highest spikes comes at a text that the user added at the end of the calendar (fig. 40). This text, called the Colnish Pater Noster, asks the votary to read the phrases of the Pater Noster into the wounds of Christ’s body. As we saw above, owners showed a special interest in the texts they added, which makes sense, since they must have personally selected them and gone to some extra effort to include them.

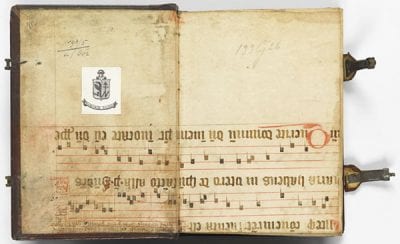

V. Utrecht, Catharijneconvent, BMH h 64

This manuscript is a Latin book of hours, written in Delft (based on stylistic grounds) and dated 1456, according to a text accompanying the calendrical tables for calculating Easter (fig. 41). It contains red and blue penwork of a style associated exclusively with Delft (fig. 42). The manuscript was written on exceedingly thin and fine parchment of a variety I have been able to connect to the two main Augustinian convents of Delft: one dedicated to Saint Anne, the other to Saint Agnes. An Augustinian canoness from one of these convents may have been the manuscript’s original owner. The convent of St. Agnes is known to have produced manuscripts; it produced Brussels, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 21696, discussed above, and may have also produced this one. The convent of St. Anne is a less likely candidate for the production of this manuscript, as Saint Anne is not even mentioned in the litany. Only the Augustinian convents produced and used manuscripts in Latin; the Franciscan sisters in Delft appear to have made manuscripts only in Dutch.

Each folio in this book of hours reveals a slight darkening from repeated handling, demonstrating that the book was indeed used as an instrument of prayer over a period of time (fig. 43). The densitometry graph for BMH 64 reveals that the first or early owner used many of the texts in the manuscript. He or she read the Hours of the Cross approximately as frequently as the Hours of the Virgin, consulted the Hours of the Sorrows of the Virgin less frequently, and spent the most time with the Vigil for the Dead. The Vigil, in other words, is the text corresponding to the greatest area under the curve, and the edges of the manuscript folios in this section are visibly worn (fig. 44). Augustinian canonesses were remunerated for reading the Vigil on behalf of the dead in Purgatory, and it is possible that a canoness wrote and decorated this manuscript then subsequently used it to perform her duties.

Another possibility is that the manuscript’s subsequent owner was responsible for the signs of wear. The final folio of the manuscript contains a cumulative list of the manuscript’s later owners (fig. 45).15 The manuscript, which was made in 1456, was in the hands of Jacop Oem Tielman zoen, who lived in Dordrecht until his death in 1485. Jacob was the son of Tielman Oem, the mayor of Dordrecht, and Jacob himself became a city official in that city. He was married to Lutgera de Jonge, and together they had twenty children. In the fifteenth century the Oem family had important functions in the church, and some went on pilgrimage to Rome and Jerusalem. Perhaps the person who made the manuscript was a member of the Oem family who lived as a canoness regular in the nearby city of Delft. When Jacob died in 1485, he left the manuscript to his son Daniel, and the manuscript continued in the Oem family for several generations, possibly valued more as an heirloom than as a prayer book. Perhaps one of the post-Reformation members of this family was responsible for scratching out the rubrics in the manuscript that detailed the indulgences readers could earn, such as one now scraped to oblivion on fol. 94r (fig. 46).16 It is difficult to say whether reading the Vigil for the Dead on behalf of their deceased family members would have formed part of the Oem family’s outward displays of religiosity after the Reformation.

In sum, the densitometrical evidence and other internal evidence within the manuscript suggest one of two likely scenarios: either an Augustinian canoness at the convent of St. Agnes in Delft read the Vigil for the Dead intensively, because doing so was part of her duties; or a member of the Oem family of Dordrecht incorporated the manuscript into their tradition of honoring their ancestors.

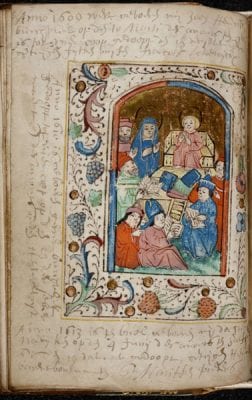

VI. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 135 G 19

The graph for The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 135 G 19 looks quite different from the others presented so far, as it has severe spikes interspersed with low valleys (fig. 47). The manuscript is a book of hours with a calendar for the county of Utrecht. It was consecrated in 1498 by Michael Hildebrand, the archbishop of Riga, and was probably produced a few years earlier in the 1490s. The manuscript is heavily illustrated with painted and penwork border decoration, historiated initials, and full-page miniatures. The painted decoration is difficult to localize but may have been executed in the Southern Netherlands. Correlating the graph with the respective openings reveals that the wear and activity in this manuscript are concentrated on the illuminated pages (fig. 48). In fact, every spike corresponds to an opening with a full-page miniature, which suggests that not only did the patron exercise an image-centered devotion, but that he preferred his images large. He mostly handled pages with full-page miniatures and was less interested in the historiated initials. Perhaps he had poor eyesight.

He was not, however, illiterate, as the densitometry graph also reveals significant areas under the curve at the gospel readings, which begin, unusually, with an image of the Annunciation (fig. 49), as well as at the suffrages and the prayers for communion. Text pages in all of these sections have been darkened with use, indicating that the owner had a sustained involvement with these texts. Within these sections, he also revealed some of his favorites, for example the suffrage to Saint Erasmus, which was considered to be apotropaic (fig. 50). (This text was also a favorite of the owner of Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. Germ. Oct. 6, as discussed above.)

The graph would suggest that he frequently turned to the Hours and Mass of the Virgin, reading just the beginning of the text then concentrating on the images. Not all of the images held his sustained attention, however. One of the low points on the graph corresponds to the image representing the Visitation, that is, the meeting between Mary and her cousin Elizabeth when the two women were pregnant with Jesus and John the Baptist, respectively (fig. 51). Whereas convent sisters performed prayers and plays and commissioned sculptures based on this event and might have been expected to hold this image in esteem, the male owner of this manuscript took no more than a passing glance at it.

Like some of the other book owners considered in this article, this one also added a section to his book, which is marked on the graph in yellow. The owner added nine folios to the beginning of the manuscript before the calendar, including a prayer to Christ (fol. 4v-6v) and a prayer to Job (fol. 7r-8v). This section contains some of the darkest margins in the manuscript and suggests that the patron was interested in the concerns of these prayers, namely penance and patience. The folio with the highest spike on the densitometry graph also falls in this added section. This miniature presents an image of the patron himself (fig. 52). This was apparently the folio to which he turned most often. From the portrait in this miniature, it appears that the owner was a nobleman (he kneels with his coat of arms before him) and not a cleric (he has no tonsure). The object of his devotion is Saint Jerome, who beats his chest with a rock while contemplating an image of the crucifixion in his hermitage. We can begin to form a picture of this votary, a man whose devotions were intensely image-centric, so much so that he chose to have himself depicted in the presence of Saint Jerome and an image of the Crucifixion, and he turned repeatedly to view that miniature.

VII. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 128 G 33

The pattern in the densitometry graph for The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 128 G 33 tells quite a different story (fig. 53). The manuscript is a book of hours with borders decorated in the so-called Ghent-Bruges strewn-flower style. In addition to depositing dirty fingerprints on the unpainted vellum, the user also wore the paint away in the corners of the decorated folios; the decorated borders with the acanthus and flowers have been severely rubbed by the user’s hands, as on the painted border below the miniature depicting David at prayer (fig. 54). This owner was intensely involved with the Seven Penitential Psalms, but his or her involvement dropped off at the litany of the saints. Correspondingly, he or she only read selected suffrages, namely those to Saint Sebastian and Saint Adrian—two saints thought to ward off the bubonic plague—but did not have a general interest in saints, and most of them have been ignored. While the suffrage to Saint Sebastian reveals evidence of its user’s fingers, a few folios further on, the suffrage to Saint Apollonia has barely been touched (fig. 55). It would appear that the owner of this manuscript did not suffer from toothache but may have had reason to fear the plague.

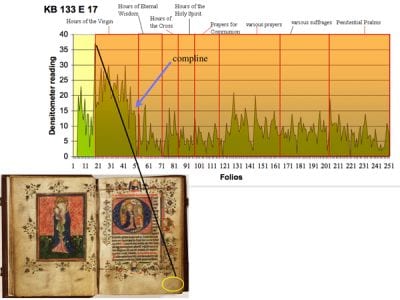

VIII. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 133 E 17

The densitometry graph for a book of hours made in South Holland, The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 133 E 17, on the other hand, reveals that its user spent the most time with the Hours of the Virgin (fig. 56). Like the reader who used Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 74 G 35, discussed above, this votary did not always stay awake long enough to read compline. The sharp see-saw tendency of this graph is probably a result of the rather rough vellum on which it was written, resulting in a remarkable difference between the hair and the flesh sides of the vellum, so that the dirt is much more likely to get trapped in the velvety flesh side, causing it to darken more quickly.

The owner clearly read the Hours of the Virgin more than the other texts in the manuscript. One wonders whether, when the owner commissioned the manuscript, she requested that this text be placed first, that is, in the privileged position directly after the calendar, because she knew from the start that she would read it most intensively. The answer to this question is unknowable, especially in the absence of an identification of the patron. Furthermore, a reader’s preferred text does not always occur early in the manuscript; there are counter-examples, such as Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 128 G 33, discussed above, in which the favored text was buried deep in the manuscript. However, the manuscripts must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and the possibility remains open that the patron actively selected the Hours of the Virgin as the first text, a position that was by no means automatic in the Northern Netherlands. The order in which texts appear in late medieval prayer books is a topic that deserves further study.

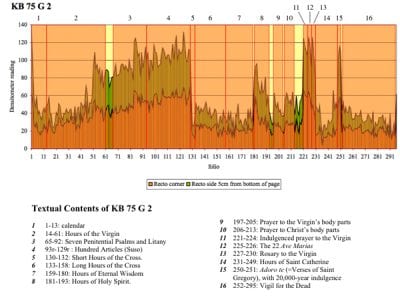

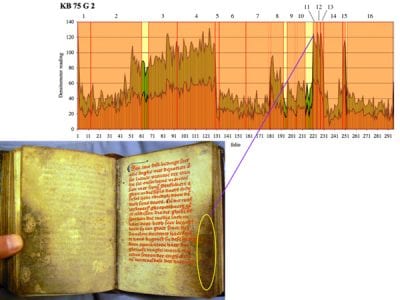

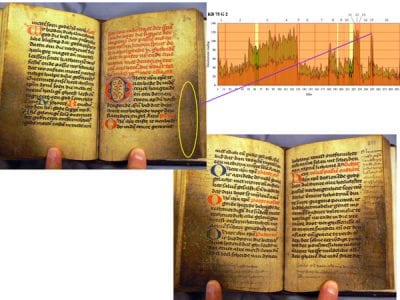

IX. The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 75 G 2

The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 75 G 2 is the dirtiest of all the manuscripts examined (fig. 57). The manuscript is a book of hours with some unusual texts, including a prayer to the Virgin’s body parts and the Hours of Saint Catherine. The manuscript also contains the Hundred Articles of the Passion, written by Henry Suso, which circulated almost exclusively in monastic houses.17 The manuscript has a calendar for the bishopric of Liège, which includes an entry for the dedication of the church at Tongeren (Tongres) (May 7) in red, suggesting that the manuscript came from a convent in or near that city. The pronouns have female endings, indicating that the owner was probably a woman. She may have come from an Augustinian convent, since Saint Augustine appears first among the confessors in the litany. One possibility is that she belonged to the canonesses regular of the convent of St. Catharine (Sinte-Katharijnenberg/Magdalenezusters) in Tienen, which is very close to Tongeren.

The manuscript has a calendar, the Hours of the Virgin, the Seven Penitential Psalms (with extra dirt at the litany of the saints), the Hundred Articles, which I will discuss presently, the Short Hours of the Cross, which are indeed very short, followed by the much more substantial Long Hours of the Cross, the Hours of Eternal Wisdom (also based on a text by Henry Suso), the Hours of the Holy Spirit, prayers to the Virgin’s body parts, prayers to Christ’s body parts, indulgenced texts (where, unsurprisingly, there is a large spike on the densitometer), prayers to the Virgin, and finally, the Vigil for the Dead. The densitometry graph reveals that the owner paid a great deal of ardent attention to several of these texts (fig. 58).

As with Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 71 G 53, discussed above, I wondered whether there was more than one user who deposited grime on this book, and I therefore measured the lower recto corner as well as a spot at a fixed distance from the lower edge. The result, once again, is that the two graphs merely reiterate each other, one at a higher amplitude. This suggests that the fingerprints were the result of a single user, who merely held the book in a slightly different way at various times. Remarkably, she used her manuscript so heavily that she left her dark, shiny black fingerprints on nearly every folio. The peaks in the densitometer graph might represent the saturation of the vellum, that is, the maximum amount of darkness that can be rubbed into the vellum in the course of handling.18

One of the sharpest spikes in the densitometer graph corresponds to the text that opens on fol. 221r (fig. 59). The verso side of the opening, fol. 220v, formerly had something glued to it, most likely an image of the Virgin. It would appear from the way that the fingerprints extend over the traces of glue that the image formerly there was worn away at some early point in the book’s career, and that its owner continued to read it intensely after the image fell out. The first recto is written entirely in red. The rubric comprises an exemplum, a story about an abbess who was lying on her deathbed and saw a bevy of devils around her. But after she started reading the following prayer, the Virgin Mary appeared, along with a flock of angels who swooped down and ejected the bevy of devils. The same is sure to happen to any pious devotee who reads the attached prayer, the rubric goes on to explain, plus she will receive an indulgence of one hundred days from Pope Innocent. How many times did the sister from Tongeren have to read this prayer in order to rub that much dirt into the vellum? Five hundred times? Thirty thousand times? How anxious was she about her death?

Turning the page reveals the beginning of this miracle-working prayer (fols. 221v-222r). This opening is even more intensely rubbed than the previous page with the rubricated indulgence. Perhaps, therefore, the votary did not read the rubric every time she read the prayer. However, the densitometer was not really able to pick up on this difference of intensity. Both folios 221r and 222r gave the same reading on the scale, which probably corresponds to the terminal amount of dirt and discoloration it is possible to apply to vellum with one’s fingers. This points to one of the shortcomings of the method, that the machine cannot make fine distinctions for the very dirtiest, nor for the very cleanest, manuscripts. The densitometer readings, after all, are only one kind of data, to which we must add textual, codicological and other kinds of observations in order to tell a more complete story about a manuscript’s reception.

One text that also saturated the densitometer is the Hundred Articles of the Passion, which begins with a prologue and a rubricated refrain (fig. 60). The text demands that the votary read while sitting, standing, kneeling, or lying prostrate on the ground, and that she perform the text every day for a week. Some of the folios are so filthy that the text is rubbed to illegibility (fig. 61). One can surmise that after this much wear, the book’s owner would have largely memorized the text, so that the remaining letters would simply function as a trigger to this memory rather than an exact blueprint for her recitation. In the process of reading it, the reader made the manuscript unusable to those who inherited it.

On the other hand, she barely touched the next text in the book, the Short Hours of the Cross (fig. 62), which is only a few folios long and quite breezy in comparison to Hundred Articles of the Passion. The low densitometer readings reveal that this text held almost no interest for the book’s owner, who apparently preferred the histrionics of kneeling and lying on the hard floor, as directed by the Hundred Articles. She may have considered the Short Hours of the Cross unsuitably brief and uninvolving. At any rate, it did not hold her sustained attention. We can begin to form a character sketch of this book owner, who relished long, difficult devotions imbued with physical hardship.

In addition to pasting in an image to preface the story of the abbess on her deathbed, the owner of the manuscript also pasted in several other images, two of which survive. One of these added images is a hand-colored print representing Christ in Agony (fig. 63). The way in which the sky is painted with a horizontal strip of blue near the upper frame, as well as the stylistic features of the print, suggest that the image might have come from Germany. The other image that remains in the manuscript represents the Virgin of the Sun and may have originated in Brabant (fig. 64). This hand-made image, while not a print, nevertheless survives in multiple copies and was probably made with a ruler, a compass, and a copied model. The owner, in other words, collected images from multiple sources and used her prayer book as a repository for those images.

The text that follows the image of the Virgin is one that received comparatively subdued interest: a prayer to the Virgin’s body parts. This prayer divides the Virgin’s body into twenty-eight parts and treats each one in turn. Most copies of the prayer demand that the reader perform the prayer in front of an image, and in this manuscript, the reader has added an image of the Virgin and Child. Within the prayer, shorter internal rubrics guide the reader along a journey encompassing the Virgin’s image, from one body part to the next, from her “glorious head” to her tiny feet, sticking out at the bottom. Telescoping from the general to the specific, the votary considers the individual components of the Virgin’s head, starting with her face, her eyes, ears, cheeks, nose, and mouth. The prayer further breaks down the components of her mouth: her lips and teeth. This array prescribes a particular way of looking the image. The prayer, however, is not very demanding, and it does not promise any indulgences; perhaps these two factors led the book owner—clearly an indulgence-smitten masochist—to give it a lukewarm reception.

One text with which she did interact strongly is the Adoro te, the indulgenced text encountered earlier. Like earlier examples, this one probably had an image of the Mass of Saint Gregory, which someone has cut out, leaving a stub behind that is visible in the gutter (fig. 65). The second folio of the prayer is even darker and more handled than the first folio. Moreover, the owner has filled the margins with more text. The Adoro te was a prayer that came in several lengths; the original version had five verses and an indulgence for twenty thousand years. After 1474, Pope Sixtus IV added more verses to the prayer and doubled the indulgence. This manuscript has the five-verse version, each verse beginning with an initial O. It appears that the owner of this prayer book may have inscribed the extra verses into the margins of fols. 250v and 251r, thereby transforming her version of the Adoro te into a longer and more richly indulgenced one. She fingered this added text so voraciously, however, that she rubbed it into illegibility. In the process of using the text, she obliterated it. Loving the words and despising them (as did the post-Reformation owners who cut the rubrics listing indulgences from their manuscripts) can achieve the same result.

Possibilities and Limitations

How do I know that the dirt is from original, fifteenth-century users? The answer is that I don’t. The material I have collected for this article, like most of the material on which we base our interpretations and narratives of the past, is evidence, not proof. That having been said, I would like to add a few points, by way of conclusion, that strengthen the case for densitometry evidence as a useful item in the toolbox book historians employ to uncover something valid about the faraway, murky, and slippery past.

The reason we can be confident that the manuscripts were fingered in the fifteenth century in the ways that I have suggested above and not by later collectors is that all the evidence conforms to our expectations of how a fifteenth-century believer might have handled his book.

First, the examples I have chosen were made in the late fifteenth century, a period when the practice of prayer was changing rapidly. I believe that most of the heavy wear in fifteenth-century books of hours comes from the original owners because such intensive use reflects the fact that people did not want old prayer books or service books in Latin: they discarded books that were out of date, written in languages and scripts they did not understand, and acquired and used instead new books that included fashionable prayers. Old manuscripts often ended up in the hands of binders who used them as padding or structural material. This practice was so common that there is even a word to describe such a recycled fragment of parchment: maculature (fig. 66).

Second, we would expect that owners who went out of their way to incorporate a particular prayer into an already finished manuscript would have shown extra attention to that text. And that is precisely what the densitometry data reveals. In the cases of The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 75 G 2, and The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 135 G 19, for example, some of the grime is indirectly datable because it is related to added script, or related to the added devotional objects in a manuscript. This is also true in The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Ms. 133 D 10, fol. 147v-148r, where the handling of the image and prayer to the Trinity corresponds to the attention the owner gave to the margin below the image, where he or she has written an inscription in a late fifteenth-century hand (fig. 39). In sum, it is both logical and borne out by the densitometer data that early owners gave extra attention to the texts and images that they added to their books.

Third, believers not only added the newest and most highly indulgenced prayers to their manuscripts, but as printing took hold in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century, it altered what people read and how they read it. People could simply purchase new prayers in the form of booklets that contained the newest, most highly indulgenced devotions, such as a booklet from 1517, which promises a plenary indulgence each time the reader completes it (fig. 67). The printing press made it cheap and easy for votaries to consume the new kinds of devotional literature they desired.

Fourth, the function of manuscript prayer books changed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as they were replaced by printed versions or made obsolete by events. Laypeople often kept older books of hours, but in the post-Reformation era, the function of those books of hours changed—they were no longer manuals for prayer but became repositories for birth, marriage, and death information. For example, the early-modern owners of a book of hours in Dutch, possibly made in Enkhuizen in the first decade of the sixteenth century, regularly added birth and death information to the ruled but otherwise blank vellum immediately following the calendar (fig. 68). North Holland, where Enkhuizen lay, became a thoroughly Protestant area shortly after the manuscript was produced, and it is unlikely that generations of subsequent owners would have used it as a manual for prayer. Likewise, the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century owners of a prayer book with printed miniatures used the marginal space around the images to note important family events (fig. 69).

Fifth, if a fifteenth-century manuscript is in a sixteenth-century binding, this is probably an indication that it was rebound because it had been so heavily used in the first decades of its production. For example, a manuscript probably made in the diocese of Liège and now preserved in Tilburg reveals signs of heavy handling: the decoration around the prayer Adoro te, for example, has been severely abraded (fig. 70). Similarly, the incipit folio of the Golden Litany of the Passion in the same manuscript has been so severely handled that the script in the marginal banderoles has been rubbed off, and wear from the user’s fingers has even digested part of the paper support (fig. 71). The manuscript must have been so worn in the late fifteenth century that it needed a new binding in the sixteenth (fig. 72). The binding is also revealing of its user’s desires: the two brass loops riveted to it would have been connected to a chain so that the owner could carry the manuscript on her arm like a purse. She clearly did not want to be separated from this book.

In the course of exploring the possibilities of the densitometer as a tool for understanding reader response at the end of the Middle Ages, I tried the technique on approximately two hundred manuscripts but achieved interpretable results in only about 10 percent of these. There are a variety of reasons for this. The manuscripts have to be quite dirty before the concentrations of fingerprints are detected by the densitometer. Some manuscripts appear to have been handled very little and therefore reveal no traces of their users’ fingers. These include very high-end productions that may have been handled through a chemise binding or other ceremonial cloth, which would have eliminated direct contact with the vellum.19 Very few chemise bindings survive, but they are depicted in several fifteenth-century paintings and miniatures, such as the framing scene in the Vienna Hours of Mary of Burgundy, in which the sitter handles the manuscript through the textile with her right hand and touches it directly with the skin of her left (fig. 73).20 Among the manuscripts that were heavily used, many were trimmed, specifically with the aim of trimming the dirty edges away. Another category of manuscripts for which densitometry is inappropriate and ineffectual are those whose borders have been overpainted, such as a book of hours from the Southern Netherlands, with illuminations by the Masters of the Gold Scrolls (fig. 74), and those whose borders were overpainted in the nineteenth century.

Finally, manuscripts that have been cleaned refuse to divulge the secrets of their early users. One example of a cleaned manuscript is London, Victoria and Albert Museum, Ms. Reid 32, a book of hours from South Holland with illuminations by the Masters of the Delft Grisailles (fig. 75). Because the manuscript has been heavily used, the margins are quite discolored; the owner even read the book by candlelight, as revealed by the pools of wax that dripped onto several folios (fig. 76). This seemed at first to be a good densitometry candidate, and when I measured the manuscript, the densitometer registered quite high numbers that revealed intensive use (fig. 77). However, the densitometry graph for this manuscript was difficult to evaluate, and the peaks and valleys only corresponded vaguely to any text divisions in the manuscript (fig. 78). A clue to the reason behind this, I believe, lies in a note affixed to the end of the manuscript, indicating that all of the folios were cleaned in February 1982. The procedure had the effect of reducing and, to some degree, redistributing the dirt, thereby nullifying the densitometry results.

The dirt ground into the margins of medieval manuscripts is one of their interpretable features, which can help us to understand the desires, fears, and reading habits of the past. Cleaning or trimming the dirt from them is tantamount to discarding a provocative cultural witness. Studying manuscripts for their dirt content cannot be accomplished by use of a digital or photographic proxy, and even the photographs published with this article do not always convey the subtleties of the dirt that the densitometer is able to distinguish. Art historians, in particular, often collect digital facsimiles of only those folios containing illumination. I believe that when they do so they omit not only the textual context but also a broader physical context that includes but is not limited to the study of dirt.

As we listen to the last gasp of the physical book, it is important to think about this material evidence and what it represents. What we have to gain by digitization and by abandoning the book as a physical object may be negated by what we have to lose. An important article by Nicholson Baker published in the New Yorker speaks to this issue. Baker decries the destruction of the card catalogue in favor of the digital catalogue, pointing out that the card catalogue, like the physical book, can preserve signs of wear in a way that its digital counterpart cannot.21

I make a similar plea that, as libraries continue to digitize medieval illuminations, they continue to grant access to the physical objects, which always hold more evidence than we first perceive. The Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague, which preserves many of the examples taken up in this study, for example, has been in the forefront of digitizing images from its illuminated manuscripts, but at the same time has reduced the opening hours of its reading rooms. But they have done so partly because the reading rooms are frequently empty. It would seem that manuscript historians are largely content to study a digital copy from home if it exists. The convenience of digital facsimiles might be heralding the end of codicological approaches to manuscript studies. This is lamentable, as there is much subtle information stored in the physical object

The preliminary results achieved with the densitometer presented above can already help us to tell more specific narratives about books and their users. The densitometry analysis has revealed patterns of wear that are valid with respect to the individual specimens. Much more data will have to be collected before one can begin to make valid claims across groups of manuscripts, although it seems, already in this limited study, that one of the surprises is the degree to which votaries read the Seven Penitential Psalms, certain indulgenced prayers, and prayers that they added to their books themselves. I suspect, but do not yet have the evidence to show, that the degree to which late medieval votaries desired indulgences put market pressure on manuscript makers, who responded to their demands by creating manuscripts with more indulgences and fewer of the kinds of prayers that votaries would ignore. Similarly, there may have been market pressure to shorten the Vigil for the Dead, one of the longest sections in a book of hours. More analysis might demonstrate that toward the end of the fifteenth century votaries were willing to buy manuscripts with the shortened version of this text, which contains only three readings rather than the traditional nine. Conversely, votaries demanded the nine-, ten-, or even eleven-verse versions of the Adoro te, rather than the old-fashioned five-verse version that promised a smaller indulgence.

My hope is that others might apply (and refine) the technique of densitometry to the manuscripts in their areas of expertise so that we can gain new collective insight into the physical manifestations of readers’ responses, and that this technique might also help to uncover aspects of readers’ responses during other periods in history.