Scholars writing about Jan van Eyck’s portrait of Nicolas Rolin in the Rolin Madonna have often described the depiction and the man negatively: while some have maligned Rolin’s appearance others have identified him as a hubristic usurper. This essay seeks to provide a more nuanced understanding of Nicolas Rolin’s patronage by examining his role as chancellor, his status as a non-noble within the class-conscious and restrictive Burgundian court, and how that has affected our interpretation of the works of art he commissioned and in which he appears.

“Cultural acts, the construction, apprehension, and utilization of symbolic forms, are social events like any other; they are as public as a marriage and as observable as agriculture.”

—Clifford Geertz, “Religion as a Cultural System”1

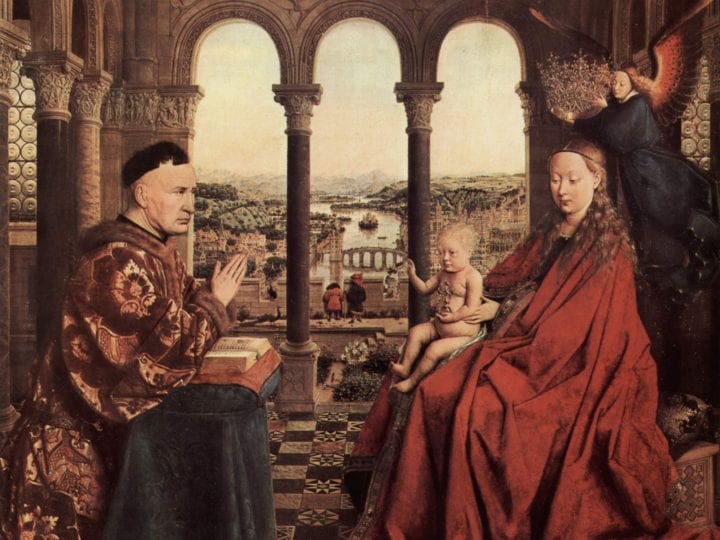

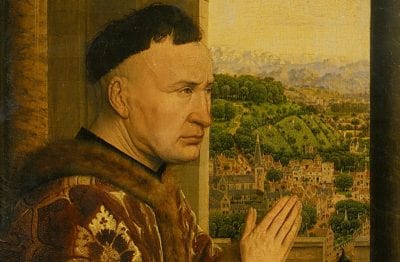

The painting Nicolas Rolin (1376-1462) commissioned from Jan van Eyck for his family chapel in the church of Notre-Dame du Châtel in Autun was but one piece of the chancellor’s publicly staged vivre noblement (fig. 1).2 Van Eyck’s painting was part of an extensive network of gifts and foundations sponsored by Rolin and the inclusion of his portrait within the painting functioned something like the donor names we still find on nearly every cultural monument. However, interpretations of the portrait have frequently identified a hubristic quality in Van Eyck’s depiction of what appears to be the patron’s equal status vis-à-vis the Madonna and Child. Negative commentary about Rolin began in his own lifetime, when commentators noted his rapacious quest for wealth and power. But no commissioner of a portrait, especially one with an intended placement near his or her place of burial, sets out to evoke a negative response. Like most important commissions, Van Eyck’s painting was the result of varied motives but foremost among them was Rolin’s wish for recognition as a nobleman who indulged in displays of magnificence, as evidenced by his contributions to Notre-Dame du Châtel, where the painting was originally located, as well as for his devotion to the Virgin, to whom the church was dedicated. Rolin was not alone in his fiercely competitive jockeying for social status at the Valois court, and jealousy of his success no doubt harmed his reputation among his contemporaries and damaged perceptions of Rolin up to the present day. This essay aims to reassess Jan van Eyck’s depiction of Rolin by examining these negative perceptions in light of his status as a member of the Valois court and by re-evaluating his charitable activities in order to come to a greater understanding of what the act of vivre noblement involved and how it affected Van Eyck’s painting.

Nicolas Rolin in the Eyes of His Contemporaries and in Ours

While Anne Hagopian van Buren believed that Rolin’s moral character was impossible to establish,3 thanks to several recent biographies and a new understanding of the intricacies of public posturing and the mutability of social positions within the court, I believe it is now possible to allow for a more nuanced interpretation of Rolin’s character than has previously been determined.4 Twentieth-century doubt about the authenticity of Rolin’s piety follows that of his fifteenth-century contemporaries, who questioned the genuineness of his spirituality. Jacques du Clercq (1420-1501) said Rolin was, “reputed to be one of the wisest men in the kingdom, to speak temporally; with respect to the spiritual, I shall remain silent”5 Georges Chastelain (1415-1475) concurred, noting that Rolin “always harvested on earth as though earth was to be his abode forever.”6 Louis XI (1423-1483) detested Rolin and said of his foundation in Beaune, “It is only right that Rolin, after having made so many poor during his life, should leave an asylum for them after his death.”7 Although his public and lucrative life probably incurred the animosity evident in these comments, they also reflect the rigid social structure of the ducal court; a system contemptuous towards non-nobles, such as Rolin.8

Rolin spent the majority of his life working for the Valois dukes of Burgundy, and while he was wealthier than many of those with titles around him, he was not noble. Graeme Small explains that, “at a court where the roturier, whatever his office or wealth, was always second-best to the noble born-and-bred, lesser social origins were an embarrassment which one did not seek to expose or explain at length. Chastelain, a prime example of this himself, reflects the values of the milieu that had adopted him in his aloof treatment of those who climbed the social ladder.”9 Chastelain was a member of the minor nobility with limited financial resources and his position at court may account, at least in part, for his unflattering description of Rolin. Peter Arnade noted that, “One of the consequences of the chronicle as literary construct is that it bears all the social marks of its court milieu, packing a host of assumptions and strategies about social worth and cultural value.”10 Far from a reliable narrator, Chastelain was deeply involved in court politics, where he was an intimate of the Croy family, whose famous rivalry with the Rolin family limited and then ended Rolin’s power in the final decade of his life.11

Rolin has consistently been viewed in a negative light from his time to ours. Johan Huizinga asked, “Are we to suspect the presence of a hypocritical nature behind the countenance of the donor of La vierge, Chancellor Rolin?”12 Negative comments by Rolin’s contemporaries caused Erwin Panofsky to characterize Rolin’s physiognomy in Rogier van der Weyden’s Last Judgment as possessing “sunken eyes, a lean, deeply lined face and bitter mouth” (fig. 2).13 Further, Panofsky referred to Du Clercq’s assessment of Rolin, quoted above, and suggested that Rolin founded the Hôtel-Dieu because of his guilty conscience.14 Panofsky described Rolin as “mighty and unscrupulous,” again quoting Du Clercq, who wrote that Rolin was “unwilling to let anyone rule in his place, intent upon rising and expanding his power to the very end and dying sword in fist.”15

Molly Teasdale Smith, writing about the Rolin Madonna, postulated that Jean, Nicolas’s son, commissioned the painting in order to expiate the sins of his father. Smith quotes Philip the Good who, upon hearing of the aged chancellor’s death, raised his arms above his head and said, “If it be possible, O Lord, my creator and his, I beseech you to pardon all his faults.”16 Instead of disparaging the chancellor’s character, Philip’s statement more likely reflects the common belief that everyone but the most saintly was bound to die with sin staining his or her soul.17 Craig Harbison also focused on the chancellor’s sinful nature, suggesting that the painting shows him in the act of confessing his sins. Harbison writes that, although “other patrons were portrayed receiving priestly forgiveness, Rolin feels powerful enough to receive absolution directly from Christ.”18 But there is no reason to believe that Van Eyck depicted a public confession nor is it likely that Rolin would have commissioned such an image.

When scholars incorporate knowledge of Rolin’s reputation into analyses of the painting his motives are usually found wanting. Hermann Kamp saw Rolin’s patronage as reflective of a desire to show himself as equal to the nobles with whom he worked; in his view the chancellor’s patronage was a form of social climbing.19 Elisabeth Dhanens, analyzing the inscriptions along the hem of the Virgin’s robe in the painting, noted that although these honorific words are usually applied to the Virgin herself, “it is possible that here the power and elevation of Chancellor Rolin is intended,” adding “here is a strong implication that the man kneeling before the Virgin has just read these texts and is aware of his own importance in the scheme of things.”20 In contrast, Bret Rothstein identifies the painting as “a carefully orchestrated display of piety,” one that “allows Rolin more or less publicly to verify an intangible—and for his contemporaries, questionable piety.”21

Panofsky described the donor portrait in the Rolin Madonna as depicting, “a human being [who] has gained admission to the elevated throne room of the Madonna without the benefit of a canonized sponsor,” asserting that the chancellor had inappropriately insinuated himself into a holy space.22 Subsequent scholars have attempted to determine the location depicted within the painting, celestial or terrestrial, and the power of Panofsky’s words has influenced numerous interpretations.23 It is important to approach the painting objectively in order to understand the formal and iconographic elements without the overlay of unquestioned aspersions on the donor’s character. Because they were looking for visual proof of Rolin’s rotten character, most scholars have misunderstood what is actually portrayed. Rather than an image of unparalleled hubris, in actuality the formal elements of the painting differ only slightly from numerous images of donors with holy figures that preceded it.24 Rolin’s placement in the painting is no more shocking or hubristic than that of Jean de Berry in the Brussels Hours or Richard II in the Wilton Diptych (London, National Gallery; fig. 3). In fact, Rolin commissioned the same type of portrait made for the nobles with whom he worked but, because he was not of noble birth, his emulation of these men may have helped tarnish his reputation in their eyes.

Status and Envy at the Valois Court

It is important to consider class, status, wealth, and envy in order to untangle the threads that led to Rolin’s tarnished reputation and the negative interpretations of his portrait. Kamp believed that Van Eyck’s painting was symptomatic of the chancellor’s anxiety about his status at the Valois court.25 Rothstein suggested that Rolin’s portrait in the Rolin Madonna acts as a form of ostentation–highlighting the chancellor’s devotional practices, while arguing against his contemporary’s perceptions of his venality.26 Descriptions of Rolin by his contemporaries make it clear that the chancellor was the subject of sharp criticism despite, or perhaps because of, his numerous donations. But, the court chroniclers who made these long-lived evaluations, men like Chastelain and Du Clercq, were envious of Rolin’s status at the court and his wealth.27 Unlike these men, Rolin was not a member of the nobility yet he attained the highest possible status at court for a non-noble, eventually even being knighted.28 In 1454, at the famous Feast of the Pheasant, Rolin was the only non-noble seated at the high table with Philip the Good.29 His wealth also opened the door for his children, allowing his sons to marry members of the Burgundian nobility.30

Rolin’s wealth and success caused his peers to envy him. Helmut Schoeck discriminated between two types of envy: one caused by righteous indignation and the other, “vulgar destructive envy,” directed toward those of similar social status to one’s self.31 Schoeck theorized that this second form of envy develops between those who are close to being equals, as was clearly the case with Rolin and his critics, all of whom fiercely guarded their positions within the court. Additionally, he writes that destructive envy can manifest itself in the desire to preserve inequality as well as in the desire for financial equality.32 Closely related to this type of envy, therefore, are the concepts of status and class. Joseph Berke offers the following definitions: “Status is a non-transferable blend of position and prestige, in contrast with class, which denotes wealth and power. These social states may complement each other, but it is not uncommon for the newly rich to have little status and for prestigious people to have little money.”33 Battles for status in the hothouse of the Burgundian court system caused the “vulgar destructive envy” that marks Rolin’s relationships with his noble contemporaries.

The comments of Rolin’s critics were the product of insecurity caused by a new fluidity in the established social order. From the twelfth century onward, an important shift marks European courts: the breakdown of traditional class barriers. Remarkable ascents were possible, but it is clear that they could be met with jealousy or even murder, as in the cases of both Thomas Becket and Robert of Aire in Flanders.34 Walter Prevenier proposes that spectacular elevations in estate became possible thanks to the new class of officials who were often better educated than those they served.35 Intermarriage was also a factor, as was the ability of the most important members of the royal entourage to accumulate tremendous wealth. Such wealth was the key to achieving nobility, but this could only truly be accomplished through strategic conspicuous consumption or displays of magnificence. Contemporaries of Rolin, like Peter Bladelin, who was not noble by birth but was extraordinarily wealthy, carried such display to remarkable extremes. As is well known, Bladelin founded the town of Middleburg, establishing a church dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul in its center and constructing an imposing castle for himself.36 Rolin’s patronage reflects a similar desire on the part of the chancellor to associate himself with the nobility and their behavior.

Chancellor Rolin and Vivre Noblement

Within the court the concept of vivre noblement, or “living nobly”, played a considerable role. When first coined this term simply indicated that one lived off income from landholding. However, as Jean Wilson has shown, by the early fifteenth century the term was synonymous with conspicuous consumption; elaborate display came to be seen as proof of nobility, acting to construct public identity and authenticate claims of noble lineage.37 Nobility is one of four types of capital enumerated and discussed by Pierre Bourdieu.38 Rolin possessed three types: economic capital, cultural capital, and social capital in spades. What he needed was the symbolic capital he would achieve by attaining noble status, because it was through that lens that all his other forms of capital were perceived. High-ranking officials in the Burgundian court, both noble and non-noble, went to great lengths and expense to show themselves as vivre noblement. Increasingly in the later Middle Ages, the greatest proof of nobility was to be found in acting noble; sometimes this was seen as more verifiable than transmission through blood. Howard Kaminsky succinctly describes this understanding of nobility: “The inner grace was a mystery, the outer signs could be perceived.”39

Acceptance by his contemporaries at court was difficult and it seems that even Rolin’s charitable acts were met with indifference (if the surviving commentaries are to be believed) if not suspicion. Lavish display formed a fundamental aspect of court life and Chastelain described in detail the various rites that took place during the three days of mourning Rolin ordered for his funeral as well as the elaborate clothing in which he was dressed for the occasion.40 In his opulent posthumous display Rolin followed the lead of the nobles for whom he worked, and he was not alone in doing so; members of the middle class and the clergy acted similarly.41 Rolin had the wealth to vivre noblement and access to the best artists, but he did not have noble blood and without this his gestures may have appeared venal and gauche to the nobles around him.

Nicolas Rolin’s Origins

Of bourgeois origins, Rolin was born in Autun in 1376 and baptized in the family church of Notre-Dame du Châtel across the street from his home.42 Nicolas’s granduncle managed to parlay a small inheritance and some good luck into significant landholdings and his grandfather was a prominent, if not particularly wealthy Autunois. Nicolas’s father was a successful landholder who transformed his financial windfall into good marriages for his sons.43 The rents and other income accrued from his properties, most of which were related to viniculture, were substantial enough that he had become fairly prominent by the time of his death in 1389, when he was buried in the Cathedral of Saint Lazare in Autun.44 Coming into a significant inheritance in his teens, Rolin pursued his studies of law in Avignon as a wealthy young man. He inherited lands in such famous wine-producing areas as Mersault, Auxey, Volnay, Beaune, and Pommard, and his landholdings became even larger following the death of his brother, Jean.45 Rolin also inherited his family’s home in Autun on the Rue de Bancs, which, throughout his long life, remained his primary residence.46

Rolin began his career as a lawyer in the Paris parliament and was quickly made chief legal council for John the Fearless in 1408. He served as a chief legal advisor and as an ambassador for the duke until John’s brutal murder in Montereau in 1419. John’s son, Philip the Good, named Rolin chancellor of Burgundy on December 3, 1422, and with this new title Rolin continued his ascent, soon becoming one of the most important diplomats on the European political stage. Rolin was charged with interpreting, negotiating and enforcing the legal rights and regulations of the duchy as well as oversight of all accounting. He served as keeper of the duke’s seal and was involved in most domestic and foreign affairs of state. Performing this service during the years in which Burgundy’s relations with France and England were particularly strained, Rolin acted as a trusted counselor to Philip the Good, helping him navigate his way through treacherous political waters. Rolin’s third marriage, to Guigone de Salins, was also his most upwardly mobile since the bride was a member of the high nobility.47 In 1423 or 1424, Philip the Good knighted Rolin, and Guigone was made a member of the duchess’s court.48

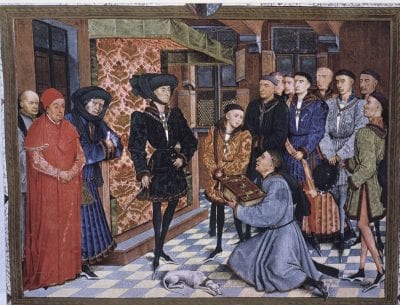

In fact, the chancellor was the most important person in the duchy after the duke himself.49 Rolin’s powerful position is clearly illustrated in the manuscript illuminations in which he is shown. In the presentation scene from the Chroniques du Hainaut by Jacques de Guise, Rolin is situated immediately to the right of Philip the Good while the duke’s son Charles is to his left (fig. 4). Rolin is shown here wearing his customary chaperon with a long cornette that wraps around the hat and over his head. The large purse at the end of a low belt acts as a symbol of his office and, in a floor-length garment, he cuts a more somber figure than the elegant duke in his fashionably short tunic.50 Rolin is depicted with slightly stooped posture showing his obeisance to the duke beside him.

As Rolin became more involved in matters of state his wealth also increased and he began to fund projects directed toward his and his family’s salvation. Nearly all his acts of beneficence were tinged with a desire for recognition, yet in this Rolin is no different from members of the Valois court on whom he modeled his patronage. Despite negative comments by his contemporaries, Rolin’s patronage does not exhibit any more self-interest or conspicuous consumption than that of the nobility. That he established foundations on a scale typically associated with that of the nobility is a reflection of the chancellor’s exceptional wealth and desire to vivre noblement rather than an indication of an unseemly desire for public display.

Establishment and Reform at the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune

Rolin’s most well-known charitable foundation, the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune (fig. 5), was endowed specifically to help the town’s poor combat the disease and famine that devastated Burgundy in the first half of the fifteenth century. Guigone de Salins was an active and involved partner in the couple’s charitable activities and the Hôtel-Dieu was one of several foundations they established together. Guigone’s family had a history of creating charitable institutions, many of which she maintained and expanded. After Rolin’s death she retired to the Hôtel-Dieu, where she was eventually buried. Guigone was not just instrumental in the origin of the hospital but was also involved with its administration and her presence is evident there to the present day.51

In 1441 Pope Eugene IV granted Rolin the rights to found a hospital for the poor.52 The same day another papal bull established indulgences for visitors to the hospital of Saint-Esprit in Besançon and alms collected there were used to build Rolin’s hospital.53 The bull also stipulated that the hospital priest in Besançon could bestow a plenary indulgence on all of those who died after confession; this included all masters, brothers, sisters, servants who had aided the sick, and persons of both sexes.54 In addition to funds raised from these indulgences Rolin pledged his own resources to the institution by providing annual revenue from salt mines in Salins.55 These mines were part of Guigone de Salins’s dowry, and she was undoubtedly involved in the decision to use the funds for this purpose.

In the foundation’s charter, Rolin noted that the hospital was established in Beaune because the city had fewer charitable institutions for the poor than Autun and it was in great need. In the first half of the fifteenth century the citizens of Beaune suffered from a combination of disease, famine, and roving bands of violent thugs known as echorcheurs. A survey taken in 1443 found that nine-tenths of the 470 households in and around Beaune were in a state of extreme poverty.56 Additionally, between 1400 and 1443 the population dropped 22 percent.57 Beaune was also a highly visible place to establish a foundation; it was the location of the parliament and the seat of justice for the duchy. The ducal palace, where Rolin stayed when in town on business, and the parliament building were adjacent to the Hôtel-Dieu. Beaune’s status as a center of high-quality wine production brought in merchants and other visitors from cities as far away as Milan and Bruges. Because the parliament met there frequently, Rolin was able to keep an eye on the hospital’s progress during construction. The Hôtel-Dieu, like all of Rolin’s charitable contributions, was a combination of public display and genuinely pious action.

After numerous appeals to Pope Nicolas V, on January 3, 1453, the Hôtel-Dieu was granted full independence.58 The pope reaffirmed all of the rights and privileges that had previously been accorded and designated them as irrevocable. With this the hospital became independent of the local archbishop and was under the jurisdiction of the Holy See, to which it owed parish rights.59 In 1455, Philip the Good visited the Hôtel-Dieu and was so impressed that he granted it tax exemptions, access to wood for heating from his forests, and, because Rolin’s initial gifts had proven inadequate for upkeep and daily needs, the duke also gave the hospital the right to accept donations and made substantial gifts of his own.60 Through his actions Philip the Good both expressed his pleasure with Rolin’s donation and associated himself with a prominent and successful foundation.

In 1459 a significant change was made to the organizational structure of the Hôtel-Dieu. With some reluctance Rolin initially allowed a rigorous monastic order to oversee the women employed at the hospital,61 but when he heard that Alardine Gasquierre, the mistress of the hospital, abused the sisters who worked there and the impoverished patients, Rolin and Guigone de Salins stepped in.62 Forming a committee with nine important residents of Beaune, Rolin drew up new rules in which he and his heirs were given complete control in the hiring of rectors, mistresses, confessors, and chaplains for the foundation.63 Job descriptions for all employees, including the mistresses, were spelled out, with an emphasis on creating a place where the poor and sick received the best possible treatment, as did their caregivers. Most significantly, the women who worked at the hospital were no longer connected to a religious institution; under the new regulations the only requirements were that they be unmarried, with good reputations, and between eighteen and thirty years of age. While employed at the hospice they were to remain chaste, but they were free to leave to join a monastery or marry if they wished. The vow that they took upon entering the foundation was simple, temporary, and revocable.64 The new regulations stipulated that the sisters were to be “gently and well-treated by the mistress, with discretion and prudence, without criticism, negative speech or jealousy.”65 New rules established how often the sisters were to confess, take communion, and say prayers for Guigone and Nicolas. These changes led to vastly improved lives for all the residents of the Hôtel-Dieu.66 Pope Pius II signaled his approval of these reforms when he reaffirmed the rights granted the foundation by his predecessors and made the indulgence granted by Calixtus III perpetual for visitors to the hospital on the five feast days of the Virgin and during the Easter Octave.67

Despite these precautions, after Rolin’s death his oldest son attempted to undermine the new regulations. Cardinal Jean Rolin, bishop of Autun, conspired with the administrators of the Hôtel-Dieu to alter the regulations for the women who worked there with a goal of reinstituting the hospital’s affiliation with a strict religious order. Guigone de Salins struggled for six years to bring the matter before the parliament of Paris and in 1469, the legality of the rules and privileges she and Nicolas had established was upheld.68 An obvious reason for Jean Rolin’s actions was that restructuring the Hôtel-Dieu’s ordinances made it exempt from the jurisdiction of all courts except for the Holy See and the foundation’s statutes specifically excluded the jurisdiction of the bishop of Autun.69 Like most important medieval ecclesiastics, Jean Rolin jealously protected the properties he oversaw and sought to increase rents and other funds that could supplement his coffers. A wealthy foundation like the Hôtel-Dieu would have provided plenty of opportunities for financial enrichment.

Rolin’s concern for the women who worked at the Hôtel-Dieu resulted in his reworking its governance and, while such restructuring was obviously important to him, it would not have interested many outside the hospital walls (his son Jean is a notable exception). Given how important these reforms were to both Nicolas and Guigone it is difficult to see their actions in anything other than a positive light. Like most charitable actions, establishing the Hôtel-Dieu was probably motivated by a complex set of concerns, including earthly recognition. But for the donors to revisit the foundation to guarantee that its patients and staff were well treated is behavior inconsistent with purely selfish motives. Hermann Kamp and Didier Sécula both attributed Rolin’s founding of the Hôtel-Dieu to his desire to emulate the patronage of the Valois dukes, but this accounts for only part of it.70 In the founding charter Rolin states that the Hôtel-Dieu was established to exchange earthy goods for celestial ones and to exchange the impermanent for the eternal.71 Similar desires are frequently noted in such documents, but in this case Rolin’s continued involvement with the hospital may indicate that with this foundation he was less concerned with vivre noblement and more concerned with genuine charity. With this in mind it is now possible to see Jan van Eyck’s painting and its donor, in a new light.

Jan van Eyck’s Rolin Madonna

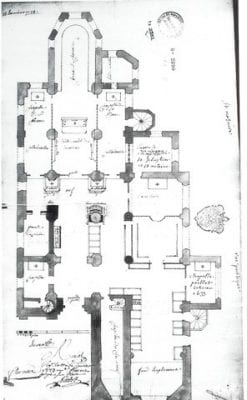

The Rolin Madonna was originally housed in the church of Notre-Dame du Châtel in Autun, a church that Rolin dramatically renovated. Rather than primarily broadcasting Rolin’s wealth or power, Jan’s painting was commissioned and composed with two main goals: the painting showcases the chancellor’s devotion to the Virgin while simultaneously connecting him to his patronage of the church. While the original location of Jan van Eyck’s painting in Notre-Dame du Châtel is fairly certain, the dating of the work is less secure with dendrochronological analysis indicating a likely execution date in the mid-1430s.72 Rolin was particularly attached to Notre-Dame du Châtel, where he was both baptized and buried. His donations to the church began in 1426, prompted by the building’s poor condition.73 Starting with funds to found and maintain a chapel, he continuously increased his donations to the building over the following decades. By 1450, he had convinced the pope to elevate Notre-Dame’s status from parish to collegiate with eleven canons (a twelfth was added in 1456), all paid for by Rolin, who was named official patron.74 Eventually the nave, choir, and chancel were entirely reconstructed and lateral chapels were added, together with a large new chapel on the south side of the church.75 Rolin also funded a tall bell tower renowned for its decorative gold tiles.76 The Rolin family house was connected to Notre-Dame’s tribune by an elevated and covered walkway that crossed the cul-de-sac du donjon, the narrow passageway that separated the house from the church.77 This allowed Rolin to access the church whenever he wished, particularly when saying Matins early, a privilege for which he had received special dispensation.78 The chancellor was buried in Notre-Dame du Châtel beneath a tomb slab that detailed his gifts to the church and other charitable activities and requested prayers from passersby.79 Thanks to the promise of indulgences for prayers said before Jan’s painting, pilgrims and others were encouraged to visit Notre-Dame and pray for its patron.80

Granting Rolin’s need to vivre noblement and the authenticity of his charitable donations allows us a new understanding of his portrait. Jan van Eyck’s painting features interior and exterior views of Notre-Dame du Châtel. By emphasizing the specifics of Rolin’s charity as reflected in the church’s architecture, the Rolin Madonna visually captured Rolin’s publicly pious behavior. In doing so, the painting followed the widely accepted pattern of announcing a patron’s gifts by showing him or her making a humble offering before the Virgin and Child. Many of the painting’s details bring to mind the rebuilding and endowment of Notre-Dame du Châtel. The Romanesque arcade behind Rolin and the Virgin resembles the arcade that separated the chapel of Saint Sebastian from the main body of the church (fig. 6).81

When the Rolin Madonna was displayed in the chapel of Saint Sebastian visitors to the church would have looked from the side aisle through the actual arcade to see Jan’s painting, which featured a similar Romanesque arcade.82 Perhaps the extension of the real church of Notre-Dame into the fictive world created by Van Eyck indicated that the Virgin and Child’s space was accessible through devout prayer as modeled by Chancellor Rolin. The mirroring effect results in a reflexive temporality, wherein the present and the past form a continuum in which the perpetual prayer of Nicolas Rolin and that of the viewer looking at his portrait unify and become more efficacious.83

The two men in the painting’s middle ground who look out over the parapet draw our attention into the distant landscape and continue the interaction of reality and fiction.84 A river divides the landscape and the city behind the Virgin and Child bristles with ecclesiastical architecture in contrast to the more secular vista to the left,85 the details of which emphasize Rolin’s pious use of the abundance depicted therein. As James Snyder noted, much of Rolin’s wealth was attained through ownership of vineyards and the verdant slope behind him attests to this connection.86 Within the city behind Rolin we find only one church and it is painted just above his hands (fig. 7): the church that is represented here is almost certainly Notre-Dame du Châtel, with its single spire covered with gold tiles, which Jan has carefully indicated with tiny dots of yellow paint, and a covered passageway to an adjacent house.87

Forcefully connecting Rolin and his landscape with the Virgin and Child, Van Eyck’s painting uses foreshortened perspective to push areas of the background into the foreground. John L. Ward noted that because of this effect the tips of the Christ Child’s fingers in the foreground seem to connect to the bridge over the river in the distance.88 The deliberate compression of space makes it look as if Christ’s gesture begins in the foreground but is carried through the background and arcs over the distant river, literally bridging the divide between the Virgin and Child’s side of the landscape and that of Rolin. Once the viewer becomes aware of this deliberate manipulation of our perception of space within the painting we naturally look for additional examples. Yet this manipulation does not necessarily reflect a hubristic view, rather, it follows long-accepted schemes for the presentation of donors.

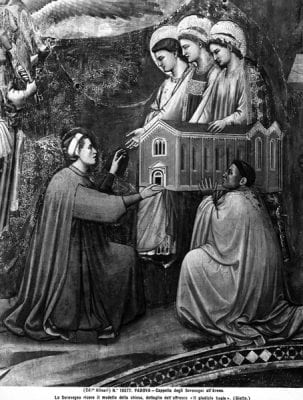

One of the most obvious of these spatial conflations is the church located just above Rolin’s joined hands, discussed above, which looks as if it is resting on the chancellor’s hands. This placement recalls archetypal donor images, such as Giotto’s famous donor portrait of Enrico Scrovegni in the Arena Chapel, shown presenting his chapel to three saints (fig. 8). By positioning the church above Rolin’s praying hands Jan cleverly conflates the image of the donor presenting a gift with that of the donor as priant, representing the prayerful devotion of the person portrayed. By fusing both portrait types Van Eyck shows Rolin as both donor and devotee and highlights Rolin’s desire to be remembered as both in perpetuity.

The crown held above the head of the Virgin in Jan’s painting may be specifically connected to one of Rolin’s gifts to the church. Rolin donated a crown to the church of Notre-Dame du Châtel that was placed on a sculpted image of the Virgin,89 and Jan’s painted crown probably refers to this donation.90 The crown has also been connected with the Coronation of the Virgin and the Virgin as Ecclesia and interpreted as the Crown of Life.91 As Ward noted, this crown creates a visual balance and iconographic correlation between its elaborate design and placement and the fictive architectural reliefs in the painting.92 These sculpted capitals show scenes from Genesis, including two specifically related to wine: the Drunkenness of Noah on Rolin’s side and Abraham and Melchizedek on the Virgin’s. Many scholars have offered interpretations about the meaning of these particular scenes, but at the most fundamental level they should be associated with the profitable vineyards that enabled Rolin to renovate the church.93 Of course, like the vineyards in the distance, these scenes also have Eucharistic references and this meaning would have been amplified by the painting’s placement near the altar in the chapel of Saint Sebastian.94

Finally, the level of Rolin’s physical and emotional engagement with the Virgin and Child deserves consideration since it is his proximity to the holy figures that has led to so much criticism. When following the path of his gaze it is clear that the chancellor looks across the center of the picture but misses the holy figures, focusing instead somewhere to the Virgin’s left.95 The two-dimensionality of Rolin’s pose allows neither the viewer nor the holy figures to engage in any sort of communication with him, and it is decidedly different from the three-dimensional placement of the Virgin and Child. Rolin’s prayerful position is calculated to appear as permanent and unceasing as possible. The Virgin looks toward him and the Christ Child blesses him, but there is no real interaction. Most importantly, a clear vertical line, like the crease in a book or the hinged frame of a diptych, separates these figures.96 Rolin and the Virgin and Child share the same imaginary space, but they should not be seen as actually inhabiting this space together.

Rolin does not have any saintly intercessors here, but he is shown at a respectful distance from the holy figures, both in terms of his physical presence and his emotional engagement. In fact, he is placed much farther away from the Virgin and Child than donors in other contemporary paintings. For example, in the central panel of Rogier van der Weyden’s Bladelin Altarpiece (fig. 9) Peter Bladelin appears without a holy intercessor and acts as a third participant in the Nativity. Like Joseph and Mary he devoutly directs his gaze toward the radiant Christ Child resting on the Virgin’s blue mantle. Rogier simultaneously includes and isolates Bladelin through formal means, such as the proximity of his hands and tunic to the edges of the Virgin’s clothing, which align without overlapping. Middleburg, the city Bladelin founded, fills the landscape beyond the ruined structure in the foreground.97 Bladelin’s long black sash directs our gaze toward the city, clearly associating the donor with his foundation.98 Like Rolin, Bladelin was not noble by birth, but his wealth and strategic display of vivre noblement enabled his meteoric rise in the Valois court. Paintings like the Rolin Madonna and the Bladelin Altarpiece serve many of the same functions and, although they are iconographically very different, they were both intended to assert specific assets of their respective donors: piety, generosity, and nobility.

The Rolin painting is a permanent evocation of his desire to vivre noblement. In terms of display and magnificence, the painting, especially when originally situated within its elaborately reconstructed and endowed setting, demonstrated Rolin’s desire to appear noble. Like the Hôtel Dieu in Beaune, his most important foundation, it served as an example of conspicuous consumption, as expected from nobility. But, as we have seen, Rolin’s hospital was also the result of his genuinely beneficent wish to help those in need. These twinned and competing impulses—genuine piety and the desire for noble status—mark Rolin’s donations, just as they do those of his non-noble contemporaries. Rolin is not exceptional, either in his supposed malevolence or beneficence; rather, he is a man of his time. However, in part because of negative preconceptions, historians have frequently branded him as hubristic and insincere and have seen his portrait as inappropriately assertive. If we, as twenty-first-century viewers, can look at Jan van Eyck’s portrait of Nicolas Rolin and, rather than seeing him through the envious gazes of his contemporaries, see what Rolin intended and what his actions as patron of both the Hôtel Dieu and Notre-Dame du Châtel reveal him to be, we see a wealthy man striving for salvation and status in a courtly world in which blood was in many ways thicker than gold.