Jheronimus Bosch seems like such an unprecedented original that accounting for his art requires going beyond the Flemish fifteenth-century visual culture that preceded him. Essentially, Bosch broke with that earlier paradigm of accessible holy figures and images that featured prayer-and-response. Instead, Bosch favored an emphasis on the presence of evil in the world and on the remoteness of the holy figures, dominated by a Christ who had suffered at human hands and would return to be severely just at the Last Judgment. This outlook is epitomized by Bosch’s emphasis in several major triptychs depicting the Fall of Humankind in the Garden of Eden. But the artist goes further: he locates the ultimate source of evil at an even earlier stage, as occurring in the skies above Eden, in the Fall of the Rebel Angels, led by Lucifer.

Several years ago I added my voice to the vast chorus of scholarly commentary on Bosch.1 Reviews of that book were consistent with most of the criticisms addressed to books on Bosch: all such volumes provide interesting discussions of context and content, but somehow none has gotten at the essence of this unique and puzzling artist.2 In an attempt to elucidate something more essential about Bosch’s artistic mission and the core of his spirituality, I offer the following essay.

Art historians always worry about origins–in the form of genealogies of training or in concerns about artistic influence. This thinking proves particularly unsatisfying for trying to explain a uniquely original artist like Jheronimus Bosch. He seems to defy such connections and to break with all precedents, particularly in terms of what he might have taken from earlier models of painting in either Flanders or Holland. Even though he stemmed from a family of painters, what strikes all observers most about Bosch is his originality, conventionally described in modern terms as his “genius.”

As the Latin saying declares, ex nihilo nihil fit, or “nothing is made out of nothing.” And as Lynn Jacobs and others have noted, Bosch utilizes the same formats as his Netherlandish predecessors, particularly triptychs. Even the shapes of his triptychs range from standard fifteenth-century rectangular wings and centers for most of his triptychs to the rounded tops more typical of sixteenth-century Antwerp.3 The use of a bell-shaped Antwerp triptych model suggests both the later date and probable workshop status of one contested triptych, the Bruges Torments of Job. Bosch also follows inherited convention in employing grisaille or brunaille tones for the exteriors of many of his triptychs, including the presentation of conventional saint figures on the outside of his Vienna Last Judgment as well as less conventional narrative scenes in monochrome on the outside of the Lisbon Saint Anthony, the Prado Epiphany, and the Garden of Earthly Delights.

Of course, the cultural inheritance of Christian thought and imagery was retained by Bosch as well: the life of Christ as well as the Christo-mimetic lives of later Christian saints, particularly hermit saints, provided him with some of his most basic themes (fig. 1). His essential repertoire consists of God, Satan, angels, and the demons of hell, especially when taken together to form the entire concatenation of the Last Judgment. This imagery certainly had firm foundations in the region, as revealed by even a cursory review of Craig Harbison’s dissertation on the Last Judgment in Netherlandish painting.4 Such imagery had long informed cathedral portals ever since the Romanesque–a commonplace, familiar to readers of this Journal. For all the emphasis on Bosch’s originality and unique genius, it is thus also quite important to recall that even for him “nothing can be made out of nothing.” As we shall see, Bosch’s formulations also lay securely founded in Christian theology, chiefly as articulated by the church father Saint Augustine, as well as other late medieval manifestations.

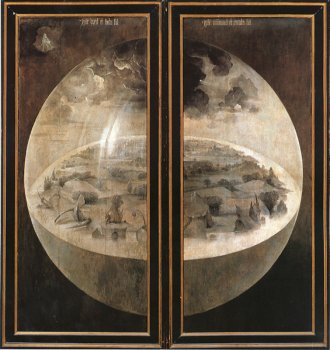

Bosch’s originality must be traced back to its own questions of “origins.” Bosch himself thematized creativity on the grisaille exterior (fig. 2) of the Garden of Earthly Delights triptych, where he shows the original creation ex nihilo, as described in Genesis, by the Creator himself. Those scholars, including myself, who see Bosch’s painted demons as an innovative watershed in the history of Netherlandish painting note that they remain his signal inventions, especially connected to his recurring novel visions of the afterlife.5 Yet this particular originality of Bosch derives from ultimate origins: God’s Creation and the Garden of Eden. Bosch was motivated by the problem of evil, particularly the origins of evil in the world; therefore, in order to trace his own originality, we must go still farther back in time, even to the moment before the advent of humanity, Adam and then Eve, to examine his frequent fascination with the Fall of the Rebel Angels. For Bosch the problems of humanity began with the origin of evil, and his representations show clearly and consistently that evil already exists in the Garden of Eden, to provide temptation for Adam and Eve. Therefore, to get a proper sense of Bosch’s creative impetus, we must first look directly into the face of Satan, by tracing his own origin: his fall from grace and divine favor in heaven, transforming him from his former angelic identity as Lucifer (or light-bearer).6

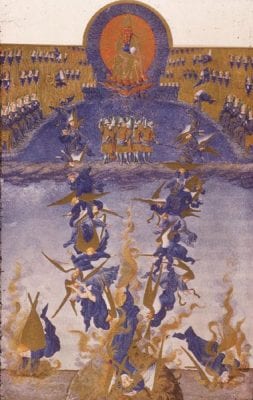

Bosch was not the first important artist to depict the origins of Satan. Another luxurious image of the Fall of the Rebel Angels appeared in the Limbourg brothers’ Très Riches Heures by the year 1416 (fol. 64v; fig. 3). The golden image of God in heaven, borne upon vermilion seraphim, sits atop the page, expanding even beyond its rectangular gold borders, while surrounded by golden choir stalls of angels clad in ultramarine robes. Closer inspection reveals empty thrones on either side within the choir space, chiefly in the forefront, vacancies occasioned by the literal fall through space of a number of gold-winged angels in blue robes, whose size increases as they approach the earth at the bottom of the page, giving off flames upon impact. These beautiful creatures are led by a crowned and fully inverted figure, who must surely be Lucifer himself. At the apex of a converging triangle of falling angels, this first among equals is the figure first mentioned by Isaiah (14:12-15):

How art thou fallen from heaven,

O Lucifer, son of the morning!

How art thou cut down to the ground,

That didst cast lots over the nations!

And thou saidst in thy heart:

“I will ascend into heaven,

Above the stars of God

Will I exalt my throne. . .

I will be like the Most High.”

Yet thou shalt be brought down to the nether-world,

To the uttermost part of the pit.

“How are the mighty fallen!” (2 Samuel 1:25) is the ultimate moral of this tale, and it is briefly reinforced in Gospel passages. First the words of Jesus in Luke 10:18, “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven,” and later in 2 Peter 2:4, “For if God did not spare the angels who sinned, but cast them down to hell and delivered them into chains of darkness, to be reserved for judgment.” In just this fashion, the monk in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, a work contemporary with the Limbourgs’ miniature, declares: “O Lucifer, brightest of angels all, / Now art thou Satan, who cannot escape / Out of the misery in which thou art fallen.” Satan’s choice to defy God’s authority and to rebel against his Lord provides the explanation for how evil could enter the world, and it offers a cautionary note that would have held powerful meaning for those princes who were patrons of both the Limbourg brothers as well as Bosch.

To understand Bosch’s powerful interest in the Fall of the Rebel Angels as the source of evil requires some attention to the theology that expounded the causes of this watershed event. The basic understanding of the Fall of the Rebel Angels was already clearly established and lastingly influential a millennium before Bosch in Augustine’s City of God, Book 11, Chapter 13: “The fallen angels, who by their own default lost that light, did not enjoy this blessedness even before they sinned . . . those who are now evil did of their own will fall away from the light of goodness.” Indeed in Chapter 15 Augustine expressly refers to the passage in Isaiah, to declare the dynamics of the devil’s downfall, “It is not to be supposed that he sinned from the beginning of his created existence, but from the beginning of his sin, when by his pride he had once commenced to sin.” Furthermore, Augustine asserts (11.19, 11.32) that the creation of all angels emerged out of the separation of light from darkness before the fashioning of the world, “[He] was able also before he fell, to foreknow that they would fall and that, being deprived of the light of truth, they would abide in the darkness of pride.” Commenting on Job 40:19, that the devil “was the beginning of God’s works,” Augustine explains that “the devil, who was good by God’s creative act, but became evil by this own will, was reduced to an inferior status and derided by God’s angels.” (11.17). Later he echoes the verse in 2 Peter (2:4) to claim in the next chapter “that certain angels sinned and were thrust down to the lowest parts of this world.”7 The wicked are miserable, Augustine explains (12.6) “because they have forsaken Him who supremely is and have turned to themselves who have no such essence. And this vice, what else is it called than pride? For pride is the beginning of sin” (Ecclesiastes 10:13). The punch line of Augustine’s meditations on the source of evil will be fundamental for Bosch as well: “That the flaw of wickedness is not nature, but contrary to nature, and has its origin, not in the Creator, but in the will.” (11.17), as he explains, “But God, as he is the supremely good Creator of good natures, he makes a good use even of evil wills. Accordingly, He caused the devil (good by God’s creation, wicked by his own will) to be cast down from his high position and to become the mockery of His angels.” Augustine’s authority and theology remained central to medieval thought, seconded in the case of theology specifically concerning the devil a century later by the writings of Pope Gregory the Great, particularly his Moralia in Job.

Thus do Lucifer and his troops of rebellious angels initiate the course of evil into the world, in the words of Milton,

what time his Pride

Had cast him out from Heav’n, with all his Host

Of Rebel Angels, by whose aid aspiring

To set himself in Glory above his Peers,

He trusted to have equal’d the most High,

If he oppos’d; and with ambitious aim

Against the Throne and Monarchy of God

Rais’d impious War in Heav’n and Battel proud

With vain attempt. Him the Almighty Power

Hurld headlong flaming from the Ethereal Skie

With hideous ruine and combustion down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell. . . . (Paradise Lost, bk. 1, lines 34-47)

It is clear that just as God’s creation of the universe and its earthly components was the ultimate act of will, the separation of evil from good was an act of decision, a personal choice by Lucifer, who in Milton’s formulation declares, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heav’n” (bk 1, line 262).

Yona Pinson has adduced a pair of roundels from the mid-thirteenth-century Bible moralisée in Oxford (Bodleian Museum, Ms 270b, fol. 2v; fig. 4) to demonstrate how the use of theological notions about the Fall during the Middle Ages found pictorial representation.8 Beneath the medallion that shows the separation of light from dark on the first day of Creation appears another medallion showing the Fall of the Rebel Angels, employing just the same visual vocabulary, equating light with the divine and darkness with the demonic, which would remain fundamental in the visual vocabulary of Bosch.

Moreover, this association is also present in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, since the closed outside shutters (fig. 2) of this triptych already show a creating God the Father looking down from within a heavenly radiance toward the globe of the world, where shadowy dark clouds and a rainbowlike gleam on the crystal orb emphasize the contrast between light and dark. This scene is usually interpreted as the separation of land and water because of the giant terrestrial plants visible within the globe, yet significantly it clearly predates the genesis of Eden itself and the later creation of Adam and Eve. In short, this critical moment occurs during the period when the angels were created in an unpopulated universe, seemingly prior to the Fall of the Rebel Angels, which is not depicted here but rather on a pair of other Bosch triptychs. Bosch’s emphasis on creation as an act is here underscored by the artist’s choice of an inscription from Psalms33:9, “For he spoke, and it was done; He commanded, and it stood.” However, Bosch’s Latin inscription, using the Vulgate, reads, “and they were created [ipse mandavit et creata sunt].” “They” could as easily refer to angelic forces as to earthly forms or the First Parents. The emphasis remains on the act of creation, not the particular item brought into being. Earlier in the same psalm, 33, the presence of angels is intimated, “By the word of the Lord were the heavens made; And all the host of them by the breath of his mouth.” (33:6). The message of this psalm is given in its conclusion, “For in Him doth our heart rejoice / Because we have trusted in His holy name. Let thy mercy, O Lord, be upon us, According as we have waited for Thee.”

Pinson notes further that the Fall of the Rebel Angels is also one of the scenes inscribed into the text of a late medieval best-seller: the fourteenth-century Mirror of Human Salvation (Speculum humanae salvationis), where it appears in the first chapter, prior to the Fall of Humankind in Eden.9 The Speculum holds particular interest for Bosch precisely because it addresses the same fundamental problem that impelled the artist: the problem of evil and the need for grace in the wake of the Fall of Humankind. The Speculum was a book translated into German and Dutch in the late fifteenth century, published as Spieghel onser behoudenisse by J. Veldener in Culemburg (1483), so its text could have been accessible to Bosch; moreover, a French translation, Miroir de la Salvation humaine, was produced by Jean Mielot for Philip the Good of Burgundy in 1449, and its lavish cycle of illustrations features the Fall of the Rebel Angels (at left) before the Creation of Eve from Adam’s rib (at right) (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Ms. fr. 6275, fol. 2v; fig. 5).10 The text of the Speculum makes this link specific:

Lucifer set himself against his creator, the eternal God, and in an instant was thrust from the height of heaven into Hell, and on this account God decided to create the human race, through which he could repair the fall of Lucifer and his cohorts.11

Another fifteenth-century Dutch text, the Table of the Christian Faith (Tafel vanden kersten ghelove), an attack on worldly desire by Dirc van Delft, an early fifteenth-century chaplain at the court of the counts of Holland-Bavaria, also shows this view of Lucifer, who speaks as follows:

I shall climb up in heaven and above the stars of heaven shall I raise my throne, I shall sit in the mountain of the testament, on the sides of the north and shall climb above the height of the clouds and be equal to the almighty (vol. 2, 141).12

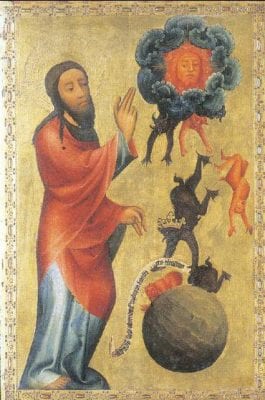

One larger pictorial cycle of Creation scenes, the Grabow Altarpiece in Hamburg (1379) by Master Bertram, also includes the Fall of the Rebel Angels as its initial image (fig. 6).13 Although this work surely was not known by Bosch, it too might derive its Creation scenes from another Speculum manuscript with the same juxtaposition derived from the common text. In this version of the separation of light from darkness, the Fall of the Rebel Angels features a falling, ape-like Lucifer who, while larger and brown-skinned, is marked with a crown and by the banderole he carries with the text of Isaiah 14:14, to assure his identity. Importantly, especially in light of Bosch’s later versions of the Fall of the Rebel Angels, Lucifer and his followers are all landing not in hell but on the globe of the earth.

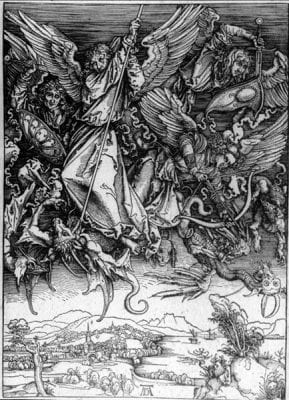

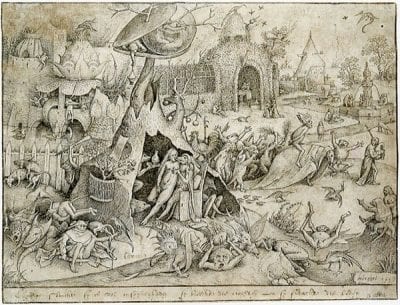

The other principal textual source for an image of a battle in heaven of obedient good angels against bad rebel angels comes from the end of time: Apocalypse 12:7-9, when the archangel Michael and his forces oppose the image of Satan in the form of a dragon, “that serpent of old, called the Devil and Satan, who deceives the whole world.” But in a curious suggestion of a cyclical echo of the initial rebellion, Satan with his minions “was cast to the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.” Nowhere is this conflict better envisioned than in the heroic conflict of large-scale figures above the clouds but also directly above the earth in the full-page woodcut (fig. 7) by Albrecht Dürer for his own 1498 publication of the Apocalypse. Perhaps with his own awareness of Bosch as a precedent, Gerard David fashioned a triptych (fig. 8) with the archangel Michael standing above the seven headed beast at the center, while in a background scene in the upper right a heavenly region with God the Father, as at the Creation moment, presides over the apocalyptic struggle between angels and falling demons. This is the same scene that Pieter Bruegel realized in his 1562 painting (fig. 9), in which the dragon-shaped beast with the seven crowned heads can be discerned, appropriately welling up from the lower reaches, amid the welter of entangled hybrid–and Boschian–demons. Appropriately the archangel appears in golden armor with a blue cloak, like the angels in the Très Riches Heures, and his heavenly minions issue downward from a great distance out of a glowing radiance.

One other Bosch work seems to hover ambiguously between the originating Fall of the Rebel Angels and the final apocalyptic struggle between angels and demons: the grisaille wing in Rotterdam (fig. 10). This offers his distinctive image of a hellish earth, with glowing skies above burning buildings at the horizon. Demonic figures hover in the sky and infest the landscape, though no angel antagonists show any battle. Two obscure figures stand in the opening to a dark cave, but their identities as an overdressed female and a crippled male do not distinguish them clearly from the cast of devils depicted elsewhere by Bosch. Thus it is unclear whether this scene shows the apocalyptic extinction by fire described in the book of Revelation or instead the origin of the myth of the rebel angels taking up residence on earth. This wing seems to have formed the left shutter of a grisaille triptych whose center is missing, which in the syntax of Bosch’s other triptychs suggests its important role as an inaugural moment. The complementary right wing, in Rotterdam (fig. 11), clearly depicts Noah’s Ark after the Flood, when the saving remnant of humanity and the animal world (including a giraffe like the one in the Eden wing of the Garden of Earthly Delights) survives to repopulate the world.

This same juxtaposition has a scriptural correlative in 2 Peter, in the chapter decrying false prophets who bring on their own destruction: “And many will follow their destructive ways, because of whom the way of truth will be blasphemed . . . For if God did not spare the angels who sinned, but cast them down to hell and delivered them into chains of darkness, to be reserved for judgment; And did not spare the ancient world, but saved Noah, one of eight people, a preacher of righteousness, bringing in the flood on the world of the ungodly . . . Then the Lord knows how to deliver the godly out of temptations and to reserve the unjust under punishment for the day of judgment, And especially those who walk according to the flesh in uncleanness and despise authority” (2:2-10). This is the voice of a preacher, castigating both lust and defiance, the double sins enacted by Adam and Eve when they ate of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Their ultimate sin, like that of Lucifer, is to have known the way of righteousness, yet “to turn from the holy commandment delivered to them” (2 Peter 2:21). And the apostle promises the sure punishment of a divine cleansing fire in the last days, “when both the earth and the works that are in it will be burned up” (2 Peter 3:10).

Bosch explicitly shows the Fall of the Rebel Angels two times on his preserved major triptychs, each time as an event in heaven above the space of the Garden of Eden. His theme is to show the corrupted world. In both the Haywain triptych; fig. 12) and Last Judgment triptych (Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste) the conflict in heaven is supervised by an oversized, frontal figure of God the Father, surrounded by golden light that features the rosy glow of adoring seraphim at its edges. From this heaven of his Haywain triptych Bosch shows the all-blue and all-rose army of good angels expelling the demons from the clouds, and these fallen angels literally tumble down to earth, morphing into winged insects or frogs as they descend.

While there is no literal depiction of the Fall of the Rebel Angels in the Garden of Earthly Delights triptych, Bosch does include monstrous animals around the fountain of Eden, including a three-headed amphibian crawling out of the pond as well as other hybrid figures never seen in any bestiary (fig. 13). The dark and ominous sump in the foreground also features composite creatures, such as a unicorn-seahorse, a flying fish, and a three-headed bird. Death also exists in Arcady: a lion devours an antelope, a cat stalks off with a mouse, and one bird monster swallows a toad.

While scholars always intuited the horror and evil associated with toads, Renilde Vervoort has taught us more precisely how this poisonous creature signifies the devil and is credited with the roots of pestilence.14 Bosch certainly used the evil toad as a symbol of lust in his hell scenes, associating it with nudes–on genitals in the Haywain or on a female nude’s breast in the Garden of Earthly Delights; moreover, the central building of hell on the right wing of the Last Judgment triptych opens through a rounded arch framed with toads.15 During this period the threat of these poisonous animals would surely have elicited the same kind of frisson often conveyed by snakes, the animal of Satan and sin in the Garden of Eden.

More emphatically, in the Last Judgment demons pervade the world, and above the left wing scene of the Garden of Eden (fig. 14) the conflict in heaven is even more energetic than in the Haywain rendition. Here, too, God appears high and frontal, the largest of all heavenly creatures, glowing rose against a golden aureole, but underneath, within the clouds, the conflict unfolds in black and white, that is light versus dark, where the lighter angels wield cross-shaped staffs and swords to subdue the rebels, who are already transforming into black-winged creatures before they fall into the colorful earth zone of Eden below. Directly beneath the figure of God, the only other figure in color is the archangel Michael with his gold armor and blue-tinted wings, so the culminating apocalyptic struggle is already anticipated in this primal scene.

These several images by Bosch of the Fall of the Rebel Angels reveal that the artist shared the common understanding of that event, going back to Augustine’s City of God as well as to recent texts and images from the Speculum humanae salvationis. His purpose in showing this subject is to note how choice and will led to Lucifer’s downfall, just as it prompted the subsequent sin of Adam and Eve, when they partook of the apple from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. For this reason, the artist featured the Fall of the Rebel Angels as the prologue in heaven to the later events that transpired with humankind in Eden. As stressed earlier, Augustine indicated (City of God, 11.17) that evil entered the world with the omniscient awareness of God the Father from the outset of Creation itself. The chapter title declares, “The flow of wickedness . . . contrary to nature . . . has its origin, not in the Creator but in the will.” And Augustine concludes by saying about Lucifer, “Even while God, in His goodness created him good, He yet had already foreseen and arranged how He would make use of him when he became wicked.”

In this context, for the Eden scenes in both the Garden of Earthly Delights and the (damaged) Last Judgment triptych Bosch includes the presence of a godhead in the Garden of Eden. This godhead bears the youthful, bearded features of Christ, in anticipation of his mission of sacrifice and salvation, which will redeem the very Fall that has not yet occurred when Eve is first introduced to Adam in the earthly Paradise. In the Judgment Eve emerges anew from the side of Adam, while in the Garden of Earthly Delights the two first human figures are introduced and paired with the divine blessing. Like angels, Augustine continues, humans also are by nature both good and bad (City of God, 12.1), and this basic difference of qualities lies in their own wills. Ultimately, the cause of their downfall, whether of Lucifer or of the First Parents, is “the inflation of pride.” Indeed, in Book 12, Chapters 22-24, Augustine explicitly asserts that the commandment in Genesis (1:28) to increase and multiply is “a gift of marriage as God instituted it from the beginning before man sinned,” a work by God which received His blessing. Augustine asserts (Chapter 23) “that marriage, worthy of the happiness of Paradise, should have had desirable fruit without the shame of lust, had there been no sin.” This suggestion is also made by Bosch in the Garden of Earthly Delights, where the blessing is bestowed, in spite of the pre-existing presence of sin and death among the animals in Paradise. Although the Garden of Earthly Delights fails to represent the Fall of the Rebel Angels explicitly, it goes on to suggest the passage of time later, between the Eden wing and the center panel. In the process, it also omits any direct rendering of the Fall of Humankind, suggesting a human potential for obedience to divine commands and attainment of salvation, even though (as the sinfulness of the central panel reveals) such obedience would not be maintained.

By contrast, both the Haywain and the Last Judgment triptychs culminate with the final Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, when an angel with a flaming sword recapitulates the expulsion from heaven of the fallen angels above. In the Haywain the sequence unfolds directly downward, seemingly inevitably, from heaven to paradise to the ultimate expulsion, whereas the Eden wing of the Last Judgment, admittedly damaged but preserved in a Lucas Cranach copy,16 offers the viewer the same kind of encounter with the initial innocence of both Adam and Eve just before their Original Sin, as in the Garden of Earthly Delights. The original creation of humanity is represented directly beneath the Fall of the Rebel Angels in the Haywain triptych, embodied through the same scene as the Speculum text: the creation of Eve from the side of Adam.

In the Last Judgment triptych the Creation of Eve is placed prominently in the foreground, where the sleeping Adam has not yet awakened, but the genuflecting and newly fashioned Eve hovers at an intermediate posture before being united with Adam in the Garden of Delights wing. It is precisely from God’s favor and protection, as evoked by this scene, that Adam and Eve are alienated by Original Sin, itself an act of will and pride that echoes Lucifer’s own literal fall from heaven. After the expulsion, humans definitively remained strangers to God and the city of God, so it is little wonder that for Bosch the Fall of the Rebel Angels and the Fall of Humankind are successive, linked events.

Bosch’s artistic enterprise, with its consistent focus on human sinfulness, derives from these very origins. The artist’s originality thus results from his profound consciousness of evil and the alienation of humanity from God.

Again in Book 12, Chapter 22, Augustine reiterates, “That God foreknew that the first man would sin.” In Book 14 Augustine teaches that the sin of the First Parents is the cause of the carnal life and vicious affections of man,” so that shame should accompany lust as its just punishment. Thus both the excess of lust and absence of shame in the innumerable sexual acts within the central panel of the Garden of Earthly Delights clearly indicate the sinful, self-indulgent nature of the humanity there. These perverse acts include inter-species fornication as well as foolish preening, what Augustine castigates as “living after the flesh (which is certainly evil).” Continuities between the Eden wing and this central panel are apparent in their shared horizon lines and hillocks as well as the repeated action of gathering fruit from trees at the right edge of the central panel. By the time of Bosch a triad of evil–“the world, the flesh, and the Devil”–had emerged as the enemy of humankind.17

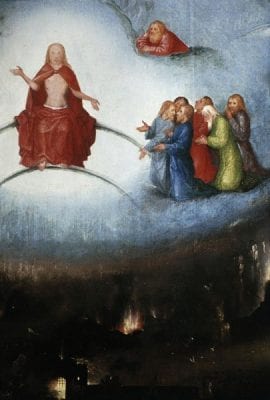

Of course, the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross offers the antidote to Original Sin, and medieval theology viewed Christ as the “New Adam.”18 But as the central panel of the Last Judgment triptych clearly reveals (fig. 15), Bosch saw the heavenly figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints as living at an impossibly distant remove; despite their celestial glow, they are represented as tiny and isolated physically from the hell on earth that dominates the apocalyptic landscape.19 Bosch underscores this contrast between heaven and an earth, where humans now are beset by demons and darkness.

His emphasis on both the Fall of the Rebel Angels and the Fall of Humankind shows how Bosch fully understood that these acts of will mark the beginning of human history, from the Expulsion to the advent of Christ, a history that has a predetermined end, the Last Judgment. Bosch’s originality stems first from his own consciousness of evil in the world and of human sinfulness–his artistry thus begins with pessimism. But his originality also resulted from his profound sense of personal alienation from the established heritage of Flemish painting he inherited. Exemplifying that tradition from Bosch’s formative period is the art of Hans Memling. The Nieuwenhove Diptych (1487), as Reindert Falkenburg has recently explicated,20 epitomizes the late medieval Andachtsbild, bringing the pious beholder into the physical presence of the holy figures, who respond directly to personal prayer. The space is a fifteenth-century domestic interior, marked with the patron saint of the donor, Saint Martin, in the stained-glass window behind the sitter. Its half-length intimacy reinforces the link between the figures, which exemplifies prayer and response, although the hierarchy is maintained by the frontal position of the Virgin and use of the division between the diptych panels in order to separate the human realm from the sacred. But this is Jesus–even a naked Jesus–as the New Adam, who accepts an apple from the Madonna but simultaneously faces Nieuwenhove and seems to proffer it to him as the symbol of redemption and grace. At the same time, the Christ Child turns outward to the viewer of the diptych; his cushion illusionistically overlaps the frame and seems to spill out of the fictive space into actual space.

Bosch never painted a diptych with a donor (or at least none that survives); however, when he presented donor figures in the presence of sacred narratives, it was usually in a setting marked by the separation between humankind and holy figures. For example, the Frankfurt Ecce Homo (fig. 16), an epitaph, shows male donors on the favorable, dexter, side of the panel, kneeling and properly humble in the corner and facing the same direction as the suffering Christ above them, whose broken and stooped body contrasts utterly with the exotically dressed henchmen who surround him. On the same level as the donors and confronting Jesus with their judgment stands a jeering crowd, filled with grotesque faces and armed with weapons bearing the markers of evil, including a halberd with the crescent of Islam and a shield with large toad. The hate-filled rabble literally declares, “Crucify him.” The very incongruity of including donors amidst this mob led a later owner of the picture to efface them. Here both the donors as well as the viewer are put into the position of judgment, asked to make a choice of compassion or condemnation, another act of will and knowledge of good and evil, but the outcome is foreclosed, and Christ must go on to die on the cross to redeem this very evil. Indeed, the prayer of the donors is also inscribed in gold letters, “Save us Christ, redeemer!” (Salva nos Christe redemptor). Of course, at the Last Judgment the positions will be reversed, and Christ will be the judge of all humanity.

In the rare cases where Bosch includes donors in his triptychs, notably the Madrid Epiphany, the presence of evil is manifest, albeit subtle, within a seemingly innocuous Gospel narrative. While the splendor of the magi seems to magnify the apparent humility of the Virgin and Christ Child, their gifts also present the discerning viewer with an imagery of evil: more hybrid monsters like those in the Garden of Earthly Delights decorate the hem of the black magus, and even the prominently placed gold statuette representing the Sacrifice of Isaac rests on the dark backs of toads. All of this is evident, whatever interpretation we give to the mysterious figure, possibly the Antichrist, in the doorway of the manger; but we can also easily discern that the grotesque faces of the retinue of the magi are as hateful as the mob in the Frankfurt Ecce Homo.21 Here, too, while we can still see what Bosch owes to the heritage he stems from, for example, Hugo van der Goes’s Monforte Altarpiece (Berlin), it is equally evident that here the separation of the holy figures is one of kind, not merely of degree.

This observation about Bosch reveals a fundamental truism: the artist’s originality results from his own differentiation from, even defiance of, pictorial tradition. Bosch’s obsession with evil overrode any sense of continuity he might have felt toward the positive and personal relationship with the divine that underlay fifteenth-century Flemish painting. Hence his visual cosmos begins with the Fall of the Rebel Angels and the Fall of Humankind, not with the scenes of the Annunciation, the Nativity, or the Adoration of the Magi that dominate the triptychs of Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, and Memling. Even his Vienna Last Judgment, filled with burning brimstone and infested with demons, differs utterly from the literally balanced cosmic decision-making made by Van der Weyden (Last Judgment, Beaune) and followed by Memling (Last Judgment, Gdansk).

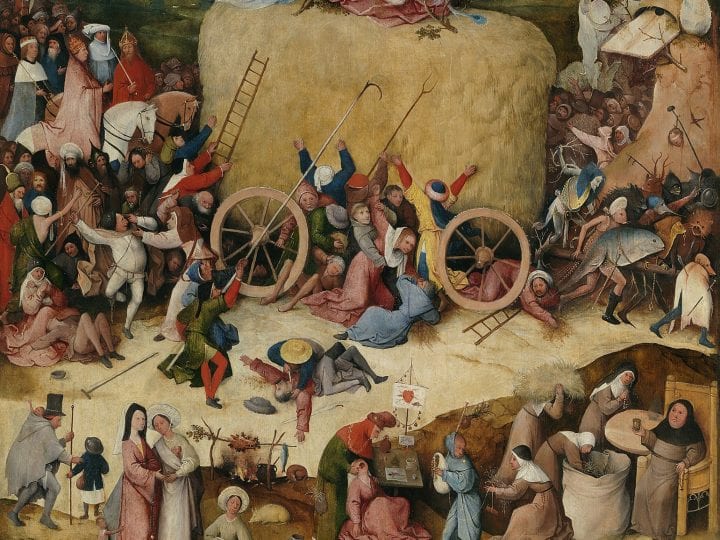

One final observation concerns Bosch and his patrons. In the Garden of Earthly Delights and elsewhere Bosch distinctly personalizes his indictments, by extending his warnings about human evil to encompass even his noble patrons, in this case the counts of Nassau. Bosch was extremely class-conscious, as the centerpiece of the Haywain triptych (fig. 17) reveals, with its mounted noble riders, literally chevaliers, lording their position of patrician privilege above the struggling pedestrian plebeians. In similar fashion, the sin of Luxuria, enacted in the central panel of his Garden of Earthly Delights, connects to the aristocratic tradition of courtly love gardens, which would have been an indulgence available chiefly to the wealthy, like his workshop’s depiction of Luxuria in the Seven Deadly Sins tabletop.

Possessions and documents abound in the Hell panel of the Garden of Earthly Delights. In the lower right corner, wearing the habit of a nun, a pig, the animal that traditionally embodies Gluttony, embraces a nervous, naked man while pressing a quill pen into his hand for a signature on a legal document, marked by a pair of bright seals. In front of this unequal couple, a monster with a bird’s beak crouches within a larger knight’s helmet and holds the ink and quills. Behind these figures, a human messenger bears additional sealed documents; however, his golden badge is surmounted by another toad (the animal used by Pieter Bruegel as a symbol of avarice in his 1556 drawing of the vice). Indeed, these components of wealth and status are precisely the worldly possessions to be found in the hands of demons at the foot of the bed in Bosch’s panel, Death of the Miser (Washington, National Gallery of Art; fig. 18).On the opposite side of the Hell scene in the foreground, Bosch shows other individuals surrounded by the instruments of games and gambling: dice, cards, and a backgammon board, as well as the quintessential aristocratic pleasure, the hunt, here reversed into the capture of a hunter by his rabbit prey (the same subject as Bruegel’s 1560 etching, The Rabbit Hunter).22 And of course just above these scenes the perversion of music pleasures also depends on sybaritic court activities. In all of these images, Bosch subverts and criticizes the courtly customs of his aristocratic patrons. The originality of this artist derives in large measure from his contrarian impulses and his acute consciousness of all human evil.

Thus our observation, which began with the question of the origins of evil, has returned us to the originality of Bosch. For the artist developed his artistry, his distinctly personal authorship, even his pictorial authority through the same act of will, which like in the case of Lucifer himself, emerged as an act of defiance. The personal development of Jheronimus Bosch could only emerge from the comfortable tradition of a family of painters and a heritage of Flemish art through a personal turn–a choice to focus upon the dark side of humankind, which dominated his oeuvre from start to finish. Like Lucifer or Adam and Eve, Bosch could not content himself with the status quo of pious prayer, nor escape the quest for knowledge and the anxiety of morality. Like Milton, he set out to show a Paradise Lost, “to justify the ways of God to man,” but unlike Milton he did not see Lucifer as a tragic hero. For Bosch, judgment remained absolute, human sinfulness irreversible.

But in making his own personal choice of Christian themes and fashioning his own visual originality, he opened up new possibilities for art-making–imagery centered on moral choice and temptation. See, for example, Joachim Patinir, Charon, Madrid; Quentin Massys, Ill-Matched Pair, Washington; Massys/Patinir, SaintAnthony, Madrid; and Pieter Bruegel, Luxuria, Brussels (fig. 19). Later Flemish painting of the sixteenth century thematizes the inevitable weakness of the flesh (Bruegel, Luilekkerland, Munich, and Triumph of Death, Madrid). From Bosch’s own origins and authority came in turn the later innovations and originality of the new century’s imagery in the Netherlands.

One final, fully speculative note: if Albrecht Dürer was capable of giving the epitome of his own self-image in the form of the Creator (Munich, Alte Pinakothek), incorporating the iconic visage of Christ,23 then we can only imagine that if Bosch had been inclined to produce a self-portrait, his sense of human and personal sinfulness might have impelled him to fuse his own features with those of Satan.24