Although Willem de Poorter (1607/08–1648 or after) is generally mentioned in art-historical literature only in relation to the role of Rembrandt (1606–1669) as teacher, he is unlikely to have trained with him in Leiden. De Poorter’s earliest extant paintings are more closely related to the work of a number of Haarlem painters than to Rembrandt’s. His drawn copy after Rembrandt’s Susanna (Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin) of 1636 suggests, however, that the Haarlem artist may have briefly worked under the latter’s supervision in Amsterdam in the mid-1630s.

The Haarlem painter Willem de Poorter (1607/08–1648 or after) belongs to a group of Dutch artists who are generally mentioned in art-historical literature only in relation to the role of Rembrandt (1606–1669) as teacher. It remains a matter of debate whether De Poorter learned his skills under Rembrandt, and it was one of the many subjects I discussed with Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann during my regular Friday-afternoon conversations with him in the late 1990s. De Poorter was the subject of a thesis I had submitted to the University of Leiden prior to becoming a student at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Egbert’s astute observations on pupil-teacher relations helped me to sharpen my ideas on De Poorter’s possible apprenticeship with Rembrandt. This article in homage to Egbert provides the reader with some of the conclusions I reached at the time together with the results of more recent research.

The assumption that De Poorter studied under Rembrandt dates back to at least the mid-eighteenth century. The earliest mention of a link between the two artists in the literature appeared in Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn’s Lettre à un Amateur de la Peinture (1755): “suivant une espece de tradition, il étoit Elève de Rembrandt.”1 Hagedorn’s remark implies that the idea that De Poorter trained with Rembrandt had already been around for a long time.2 Many later authors took the apprenticeship for granted. Alfred Woltmann and Karl Woermann’s Geschichte der Malerei (1888), for example, asserts that De Poorter’s oeuvre proves, on stylistic grounds, his education under Rembrandt.3 A handful of other scholars, however, were more critical or have had alternative views. Gustav Nagler, for example, drew attention to the small difference in age between the master and his supposed pupil, which was merely two years. Willem Bürger suggested that De Poorter trained with Frans Hals (ca. 1582–1666) or Anthonie Palamedes (1601–1673).4

In recent decades opinions on this issue have remained divided. Ben Broos and Werner Sumowski have been the most prominent advocates on the two sides of the debate. The former pled in favor of an apprenticeship in an article in Openbaar Kunstbezit (1971), arguing that the artist’s oeuvre demonstrates a strong affinity with Rembrandt’s biblical scenes of the 1630s.5 Broos reiterated his views in his entry on the Haarlem painter in the Dictionary of Art (1996).6 Sumowski first considered an apprenticeship “probable” in his Drawings of the Rembrandt School (1979–85), then became hesitant in his Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler (1983), and concluded negatively in the catalogue of the Hoogsteder exhibition Rembrandt’s Academy (1992): “It would only have taken the occasional visit to Leiden or to Rembrandt’s collectors to acquaint him with these examples [works by Rembrandt].”7

Scholars arguing for De Poorter’s training with Rembrandt generally agree that his tutelage would have taken place in Leiden at some point in the period 1629–31.8 After that, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam, and De Poorter was probably back in Haarlem by 1631.9 The strongest argument for a Leiden-based training is De Poorter’s repeated adoption of Rembrandt’s signature chiaroscuro, as well as various compositions, figure poses, and architectural settings from Rembrandt’s Leiden works. The Haarlem painter modeled his Resurrection of Lazarus, for example, on his contemporary’s rendition of the biblical story (now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), in terms of its overall composition, lighting, and the placement and poses of some of the figures.10 De Poorter, however, did not follow Rembrandt’s daring decision to spotlight the bystanders, rather than the protagonist, Lazarus. Simeon’s Song of Praise (fig. 1) is another example of De Poorter’s strong debt to Rembrandt’s Leiden paintings. The Haarlem painter responded to the latter’s version of the subject (Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague), appropriating its composition, disposition of figures, focused lighting, and templelike interior, although the space is of smaller proportions.11 Even the unidentified repoussé figure in the Mauritshuis picture returns with some adjustments in De Poorter’s version.12

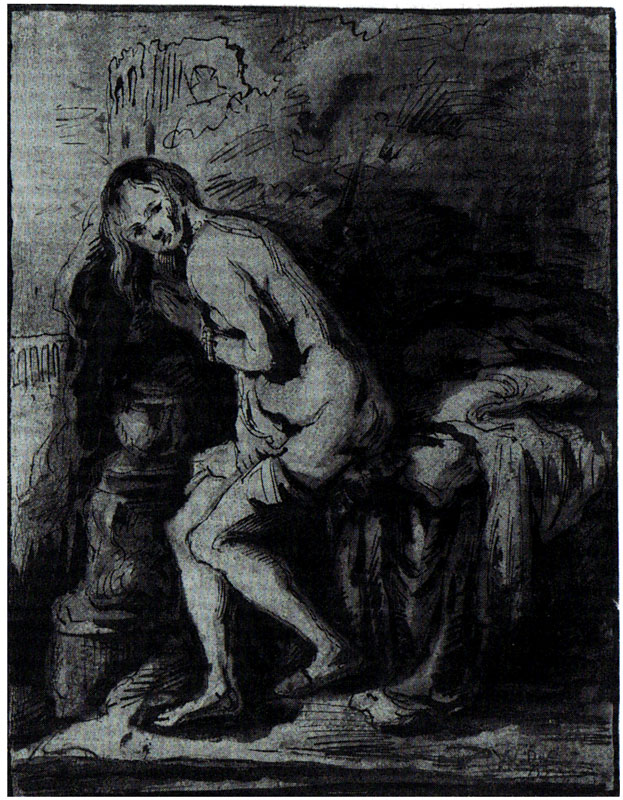

Not only works produced by Rembrandt in Leiden but also those completed in Amsterdam served as De Poorter’s sources of inspiration. The Robing of Esther (fig. 2), for example, is a variation on Rembrandt’s Heroine from the Old Testament of about 1632 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa).13 The Haarlem artist adopted the central figure, who holds her hand on her chest, in reverse, and added three female servants. A drawn copy after Rembrandt’s Susanna from the Mauritshuis also confirms De Poorter’s knowledge of and interest in the former’s biblical paintings from Amsterdam (fig. 3).14 An inscription on the sheet, W.D.P. / f. 1636, indicates that the Haarlem artist made the copy in the same year that Rembrandt completed the painting.15 I will return to this drawing later.

De Poorter’s extant oeuvre thus suggests that he studied Rembrandt’s work in-depth on several occasions. But does this mean that the former trained with the latter in Leiden around 1630? A master’s influence is usually most apparent in a pupil’s earliest paintings and diminishes during the young artist’s development of a more personal style. The extent to which an artist holds on to his/her master’s style and continues to draw ideas from the work depends upon various factors, including individual talent, artistic fashions, and demands from the market. This typical development, however, is not seen in the case of De Poorter’s relationship to Rembrandt.

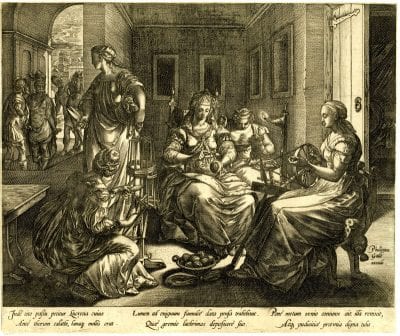

The artist’s earliest extant dated painting, Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work of 1633 (fig. 4), is not a variation on one of Rembrandt’s works but a free adaptation of an engraving of the same subject by Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) (fig. 5). Although De Poorter discarded the spindle and the spinning wheel and added an old woman to the group, he adopted the triangular format and the disposition and the poses of the central group of females around Lucretia, in reverse. As in Goltzius’s composition, Tarquinius enters the space in the left background: he is depicted frontally and his officer is rendered in profile. De Poorter did not base the architectural setting, consisting of a gray tiled floor and a bare monochrome back wall running parallel to the picture plane, on Goltzius’s invention. The space is strongly reminiscent of various contemporary Haarlem interior scenes. Diagonally placed canopy beds also feature regularly in such works. Likewise, the figures types and the use of individual bright colors set off against a monochrome background in De Poorter’s painting also recall works by Haarlem artists, in particular those of Hendrick Pot (ca. 1580–1657) (see, for example, fig. 6).

The only element in Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work that seems indebted to Rembrandt’s work is the use of light. An unseen window opening in the upper left corner allows the light to run diagonally along the back wall and spotlight five out of the six women. The female servant on the left, who is largely kept in the dark, calls to mind the blocked-out figure in the left foreground of Rembrandt’s Judas Returning the Thirty Silver Pieces of the late 1620s.16 Unlike Rembrandt’s strong chiaroscuro, however, De Poorter’s light neither blurs parts of the room, nor does it leave any of the faces unrecognizable. Strongly related in style to Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work, De Poorter’s Samson and Delilah is also among the artist’s earliest surviving works. Sumowski argued that Rembrandt’s Judas Returning the Thirty Silver Pieces served as the primary stylistic example for this work, but this statement is untenable.17 Like Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work, the painting shares only its lighting with some of Rembrandt’s works of the late 1620s and early 1630s, but the architectural setting, coloring, and figure types remind us of works by Haarlem painters such as Pot. Bernadette Van Haute has argued that De Poorter’s painting is a compositional variation of a painting of the same subject by Willem Bartsius (ca. 1612–1639 or after), an artist from Enkhuizen, who, like De Poorter, painted some of his earliest works in a style reminiscent of Pot.18 The age difference of four years between the two artists, however, makes it more plausible that Bartsius followed De Poorter, rather than vice versa.

De Poorter’s Tarquinius Finding Lucretia at Work and Samson and Delilah thus have strong ties to Haarlem but relate only superficially to Rembrandt’s work. The same is true for other paintings by De Poorter that can be dated to the first half of the 1630s. Yet several of his works of the 1640s, including The Resurrection of Lazarus, Simeon’s Song of Praise, and The Robing of Esther (fig. 1, fig. 2), confirm that the artist studied Rembrandt’s works in far greater detail and appropriated a wider range of elements from the older artist’s works later in his career. This development is not in accordance with what one might expect in the case of a pupil-master relationship.

An additional argument in support of De Poorter’s apprenticeship under Rembrandt in Leiden can also be refuted. In the Dictionary of Art (1996), Broos argued that: “it seems likely that De Poorter received his training in the Leiden workshop, where Gerrit Dou had also been working since 1628. Dramatic lighting, ‘fine’ painting in the manner of Dou and preference for still lifes (a Leiden specialism) remained characteristic of De Poorter’s oeuvre.”19 It is true that many of De Poorter’s paintings include impressive still lifes, mostly consisting of silver, gold, and other metal objects. Fully aware of his talents, the artist repeatedly chose (sometimes obscure) subjects that allowed him to include various reflective objects. He even painted a handful of independent still lifes with breastplates and shields, as well as allegorical depictions of men in armor.20

However, Broos’s statement has a number of problematic aspects. First, the brushwork De Poorter employed to imitate metallic, silver, and gold surfaces is slightly loose and creamy and does not look like the meticulous technique of Dou. Second, few metal objects appear in Dou’s early work. The only early picture by Rembrandt that includes a substantial amount of metalware is his Unidentified History Piece in the Leiden Lakenhal,21 and it would be too far-fetched to suggest that De Poorter’s specialism derived from a single picture. Third, Broos’s remark suggests that De Poorter would have had to travel to Leiden to be exposed to a strong still-life tradition. A short walk to the local workshops of Pieter Claesz. (ca. 1597–1660) and Willem Claesz. Heda (1593/94–ca. 1680/82), however, would have provided the young artist with copious examples of first-rate still lifes. Moreover, De Poorter was undoubtedly aware of the vanitas allegories by some Haarlem figure painters, including Pot, depicting men and women seated next to a table filled with an array of still-life objects, including silver and gold jewelry and vases (fig. 6). Fourth, if Broos’s assertions are true, one would expect to find various still-life objects in De Poorter’s earliest surviving paintings. Yet they play only a minor role in these paintings (see, for example, fig . 4). Gold- and silverware became more dominant in De Poorter’s work over the course of the 1630s, particularly in his depictions of Old Testament and mythological sacrificial ceremonies. Many of these are indebted to the work of Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), who painted a number of sacrificial scenes in which worshippers have brought silver and gold vases, jugs, and trays to the altar.22 In short, it is more likely that De Poorter’s preference for metal objects originated from Haarlem still lifes and vanitas allegories and Lastman’s sacrificial scenes than from Dou’s youthful works.

All in all, it appears that De Poorter’s earliest known paintings are not strongly linked to Rembrandt and his studio in Leiden. We can only conclude that the Haarlem artist is unlikely to have been one of Rembrandt’s earliest pupils. However, De Poorter’s drawn copy after Rembrandt’s Susanna (fig. 3) suggests that he may have had access to the latter’s workshop in the mid-1630s. Recent research on this painting by Petria Noble and Annelies van Loon has confirmed old suspicions that Rembrandt originally filled in the top corners of the painting to give it an arch-shaped format. During a later intervention, a restorer overpainted the corners and gave the picture its current rectangular layout.23 As De Poorter’s drawing has a rectangular format, it is tempting to think that the artist either saw the painting before Rembrandt had completed it or copied some sort of preparatory sketch that lacked a rounded top.

Close comparison between the drawing and the Mauritshuis painting, however, reveals more discrepancies. The composition of the drawing extends on the right and at the bottom beyond what originally could have been seen in the painting, that is, before a narrow strip was added to the right.24 The left side and the top of De Poorter’s sheet, on the other hand, show less than what is visible in the painting. Thus, while Rembrandt placed Susanna more or less in the center of the composition, De Poorter positioned her distinctly left of that point. Furthermore, the elder who spies on Susanna from the top left of the painting is absent in the drawing. Finally, various proportions and the distances between Susanna’s body and objects near or behind her are dissimilar. The knees of De Poorter’s Susanna figure, for example, are closer to the urn than those of Rembrandt’s figure.25

The differences between the two works confirm that De Poorter did not copy Rembrandt’s painting as a faithful aide-mémoire, which could have served as the departure point for his own version of the biblical subject.26 Had he done so, he would have executed it in his own personal drawing style.27 Rather, De Poorter used a sketchy, summarizing technique that, despite its somewhat clumsy execution, looks distinctly Rembrandtesque. The drawing therefore is not only a copy of a painting by Rembrandt, it is also a deliberate imitation of the Amsterdam artist’s drawing style. This is significant, as none of the Haarlem artist’s paintings of the mid-1630s show signs of him approximating Rembrandt’s painting technique. This begs the question: where did De Poorter learn to adjust his drawing technique to make it look Rembrandtesque?

Just as De Poorter’s shift in technique and style was the result of a conscious artistic process, so may have been the discrepancies between the drawing and the painting. One wonders whether he might have made the drawing under the guidance of Rembrandt. The Amsterdam artist may have encouraged him to make variations on his composition as a sort of exercise in a drawing class in his workshop.28 The result, however, is not entirely convincing. None of De Poorter’s changes are real improvements to the composition.

The idea that De Poorter completed this sheet under Rembrandt’s supervision when he was already in his late twenties is plausible. A handful of artists studied with Rembrandt even though they had been active as independent painters elsewhere; others took drawing lessons with him at an advanced age. Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680), for example, trained with Rembrandt in the second half of the 1630s even though he had been registered as a painter in his hometown of Dordrecht and had reached the age of twenty.29 Johannes Raven (1634–1662) may have made a handful of drawings after nudes under Rembrandt’s guidance in the 1660s, even though he was in his early thirties and had been documented as a painter by 1659.30 Finally, inscriptions on drawings by Constantijn à Renesse (1626–1680), “a patrician amateur” indicate that he was an occasional participant in Rembrandt’s drawing lessons around 1649/50. Renesse was in his mid-twenties by then.31 Moreover, a drawing occasionally attributed to Renesse depicts Rembrandt and four men drawing after a nude model (fig. 7), one of whom (bearded and wearing spectacles) is evidently older. Although the sheet of ca. 1650 does not represent the workshop situation of the mid-1630s, it does suggest that mature men attended Rembrandt’s drawing classes at a later point in time.

To summarize, De Poorter is unlikely to have been Rembrandt’s student in Leiden, but the possibility exists that he briefly worked under the latter’s supervision in Amsterdam in the mid-1630s. De Poorter’s dependence on Rembrandt’s style and compositional innovations is fascinating. It proves that Rembrandt’s work had a stronger and more longer-lasting impact on some of his followers, including De Poorter, than on some of his documented students, such as Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) and Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678).