This essay analyzes Pieter Saenredam’s The Old Town Hall of Amsterdam (1657) together with its pendant, the dedication poem by Constantijn Huygens, both of which originally hung in the burgomasters’ chamber of Amsterdam’s new Town Hall. As it was witnessed by the burgomasters in situ, I argue that the painting had a morally uplifting effect upon its audience, an effect I will define as the sublime. This definition of the sublime as encouragement to virtue is drawn from Franciscus Junius’s The Painting of the Ancients (1638), the first modern treatise on the arts to incorporate Longinus’s classical rhetorical work Peri hypsous (On the Sublime).

In his biography of Pieter Saenredam in De groote schouburgh (1718) Arnold Houbraken cites a single painting, The Old Town Hall of Amsterdam (1657), “which alone,” he says, “is enough to keep his artist’s renown alive for eternity”(fig. 1).1 The Old Town Hall is unique among Saenredam’s works in that we know its original physical context, the burgomasters’ chamber of Amsterdam’s new Town Hall. The Teylers Museum in Haarlem preserves an anecdote in the painter’s own hand, illustrated by a color sketch of the composition in miniature,2 which tells us that,

in the year 1658, on July 30, the lords treasurers of Amsterdam . . . accepted this painting by order of the lords burgomasters, and paid for it on July 31 . . . in the sum of 400 guilders in all courtesy and friendliness, accompanied by promises to consider me more in the future, [and] ordered that this piece would remain hung in the burgomasters’ chamber.3

The painting is later recorded there by Olfert Dapper in his Historical Description of the City of Amsterdam (1663), where, he says, it was pendant to the framed dedicatory poem on the new Town Hall by Constantijn Huygens.4

The prestige of this context can hardly be overestimated. A grand experiment in classicist design by Saenredam’s friend, the architect Jacob van Campen, the new Town Hall was praised as both the expression of Amsterdam’s great prosperity and a celebration of the recent peace between the United Provinces and Spain (fig. 2).5 The burgomasters’ chamber formed the heart of this building. It was the room from which the burgomasters determined the course of Amsterdam’s affairs and, through the wealth generated by the city’s trade, influenced the direction of the United Provinces themselves. The Old Town Hall and Huygens’ calligraphic poem were located within the chamber to the left of the entrance to the proclamation gallery, so Dapper tells us, where official pronouncements were read out by the burgomasters overlooking the Dam square.6 In this position, painting and poem hung directly across from the seat of the head burgomaster, and thus were always in his field of vision. The central questions of this essay are what effect these objects might have had upon their limited but distinguished audience and to what end.

There is a contemporary reaction to the painting as it was seen in the chamber, recorded by Pieter Rixtel in his poem, On the Town Hall of Amsterdam (1669). The effect of The Old Town Hall, Rixtel tells us, is that the “burgomasters’ chamber still draws glory from that old splendor.”7 Though it sounds like rhetorical praise, the description offers an important clue as to how the painting functioned in its context. When Houbraken reproduces these and some preceding lines in his biography of Saenredam, he inadvertently glosses them as he introduces them into his text. He tells us that the new Town Hall, the living subject of Rixtel’s poem, “rises up upon its old glory,” as it witnesses Saenredam’s painting, “and thus speaks.”8

This sense of elevation, evoked in Houbraken’s text through the verb zich verheffen, “to rise,” is one of the characteristic effects of aesthetic experience as defined by the Dutch scholar Franciscus Junius in The Painting of the Ancients (Latin, 1637; English, 1638; Dutch, 1641). As Junius tells us,

Although now fairenesse of beautifull bodies doth very much take our minds, yet are wee more ravished by an accurate Imitation of this same beauty: for our thoughts cheered up and elevated by the contemplation of an absolute Imitation of perfect beautie, cannot containe themselves any longer, they doe leape as it were for joy, being extolled with the gallant bravery of what the eye beholdeth.9

Junius’s book is a compendium of classical citations, primarily on oratory and poetry, shaped by the author into a discourse on the visual arts. It is at once the first work of modern art criticism to engage substantially with the classical rhetorical treatise of Longinus,10 Peri Hypsous (On the Sublime).11 In the passage above, Junius defines the experience of beauty in art by drawing on what Longinus calls the “true sublime” in oratory: that which “naturally elevates us: uplifted with a sense of proud exaltation, we are filled with joy and pride.”12 In this essay, I will argue for the sublime effect of The Old Town Hall upon its audience. In doing so, I will identify sublimity with Longinus’s notion of the morally uplifting as it is adapted by Junius in The Painting of the Ancients. While Houbraken’s lines appeared in the eighteenth century, I will argue that they do not represent an anachronistic reading of Rixtel’s poem but suggest what was the elevating effect of The Old Town Hall upon the seventeenth-century burgomasters of Amsterdam.

As Gary Schwartz and Marten Jan Bok so warmly phrase it, The Old Town Hall “shows that architectural portraiture as Saenredam practiced it, far from being eccentric or marginal, spoke straight to the heart of the political shapers of the Dutch Golden Age.”13 Whether from its conventional, topographic appearance, however, or its divergence from the perspectival interiors commonly associated with the painter, the work has suffered relative neglect in the literature.14 Moreover, it has never been considered in relation to its pendant, the dedicatory poem by Huygens. The spirit of ut pictura poesis inspired the decoration of the new Town Hall throughout, from the use of Ripa’s Iconologia in the iconographic program to the verses composed by Vondel as written accompaniments beneath individual paintings.15 To fully understand Saenredam’s work, it should thus be analyzed in concert with the motives of the dedication.

Huygen’s poem was a response to accusations of the worldly vanity of the new Town Hall as it threatened to rise above the adjacent Nieuwe Kerk. As I will demonstrate, the building’s size was critiqued as an expression of the irreligious pride of the newly wealthy city, a luxury that broke with a humble but pious past. Huygens claims that the building rather embodies the godly wisdom of the burgomasters, a quality possessed by their forebears that will only grow with subsequent generations. I will argue that the sublimity of Saenredam’s painting established this continuity with the past, inspiring the burgomasters to virtue by the example of their predecessors.

In identifying the sublimity of the painting, I will begin tentatively with what Junius calls “accurate Imitation.” As the inscription on the work itself attests, it was “first drawn after life, with all its colors.” Junius, however, argues that the artist must strive for more than verisimilitude. Lifelike rendering must be employed to uplift the viewer morally, he tells us. Junius’s source for his conception of the sublime, the Peri hypsous, is after all not only a manual of style; its final chapter offers a cultural critique in which the sublime is posited as the antithesis of conceit and luxury, the vices, we are told, that had come to extinguish truly elevated natures in the author’s time. For the critics of the new Town Hall, its expense symbolized the advent of a similar period of decadence. By reviving the virtue of the previous generation within the building, Saenredam’s painting guarded the city’s leaders against the corrupting influence of their newly gotten wealth. As I will demonstrate, the image of the old Town Hall was bound up in popular literature with the wisdom of the former burgomasters themselves, whose godly virtue was described in metaphors of physical elevation. Saenredam’s vivid depiction of the building called forth “that old splendor,” in Rixtel’s words, elevating the spirits of the sitting burgomasters before the lofty presence of their forebears. In this way, the painting answered the charges against the new Town Hall of vanity and the consequent break in time. It evoked the wisdom of the city’s former leaders within the burgomasters’ chamber, legitimizing the size of the new building by inspiring its occupants to good governance.

The Genesis of The Old Town Hall

Construction of the new Town Hall began on October 28, 1648, with the ceremonial laying of the first stone.16 The final choice of Jacob van Campen’s design, the largest of those submitted, was inspired by the confidence that filled the city after peace with Spain was declared in June.17 With the Treaty of Munster, the blockage of the Scheldt that directed trade away from Antwerp and toward Amsterdam was secure. For a time, so was the future of the city itself.

While popular literature connected the establishment of the new Town Hall directly with the peace, general planning for the building had long been under way. The old Gothic Town Hall was rotting, cramped, and no longer suited to the needs of a capital that saw itself as a rival of Venice or ancient Athens. On January 28, 1639, the proposal for a new Town Hall was taken up with the city council by the burgomasters, who complained that their current home was so ruined that an accident was imminent. The planning for a new seat of government began the following year.18 To clear ground for the new construction, all but the foremost portions of the old Town Hall were demolished. On July 7, 1652, the upper floor of the building’s tower caught fire, reducing what was left of the complex to a precarious shell. “You were galled to continue slaving,” as one contemporary poem addressed the burned building, “and so you let yourself be buried alive under ruins upon your own simple floor.”19

Saenredam’s inscription on The Old Town Hall recalls the fire and gives us a brief account of the painting’s origin: “This is the old Town Hall of the city of Amsterdam, which burned in the year 1651 [sic], the 7th of July, in 3 hours time without more [buildings]. Pieter Saenredam drew this first after life, with all its colors in the year 1641. and painted it in the year 1657.”20 The final painting shows a close-cropped, horizontal view of the adjoined buildings that formed the complex on the Dam. From left to right, we see the edge of a house cut by the work’s frame; then a view down the alley that ran alongside the medieval St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, which stretches out behind the tribunal; at center and to the fore the tribunal itself; then the tower, in which the former burgomasters’ chamber was installed; finally, at right, we see the white-plastered, gabled building whose ground floor was occupied by the city bank.21

The brick, plaster, and sandstone of the buildings are painted in creams and pastel greens, yellows and pinks. A few clouds dot the wan blue sky. The two clocks atop the tower read about seven o’clock. It is morning, certainly, as the light of the sun is coming from the east. Warm colors notwithstanding, the buildings are decrepit, the stone eroded on the facade of the tribunal, where tufts of weeds grow in its crevices. The gabled house at right features a corbel block at the lower left edge of the roofline, a remnant of elaborate Gothic brickwork visible in older depictions of the building but since pulled down.22

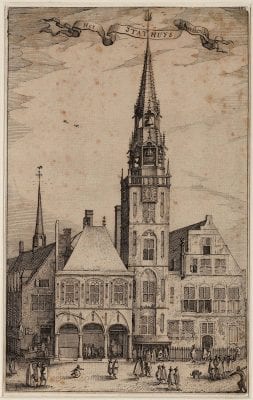

The composition itself is not original. It is derived from Jan Claesz. Visscher’s engraving of the old Town Hall, which illustrated the widely read Beschryvinghe van alle de Neder-Landen; anderrssins ghenoemt Neder-Duytslandt (Description of all the Netherlands; otherwise called Low Germany) (1612), the Dutch translation of Ludovico Guicciardini’s travelogue of the Low Countries (fig. 3). The steeple in the print, having been dismantled, has vanished from the painting, however, and Saenredam has broadened the frame to include the alley, perhaps in concession to his reputation for deep perspectival views. The facades in the painting run parallel to the picture plane, following the convention of popular topography, while the roofs and alley trail off to a vanishing point at left. The figures of black-clad burgers break up the stillness of the scene, reminding us of the continued use of the otherwise neglected structures.

Three years after the new Town Hall’s inauguration, Saenredam sold the painting of the old Town Hall to the burgomasters who, as cited above, intended it for their own chamber. As Katherine Fremantle has suggested in her classic, The Baroque Town Hall of Amsterdam (1959), there was nothing left to chance in so large and costly a building, nothing that did not harmonize with the other elements of the architecture.23 That the painting was purchased two years before the burgomasters’ chamber was completed suggests that it was part of a premeditated decorative scheme.24 However, the preparatory drawing for the work was executed long before van Campen’s final design for the Town Hall was accepted in 1648. Therefore, Saenredam could in no way have had the actual site of the painting in mind when it was likely first conceived.

The city account books note that van Campen and Constantijn Huygens were summoned to Amsterdam in 1640, immediately after the decorating committee for the building had been chosen over the period of February 15–22.25 The reason is not specified, but given the renown of both figures for their pioneering all’antica design for Huygens’ own home, and van Campen’s related design for the Mauritshuis, both on the Plein in The Hague, it can well be imagined that they were brought to Amsterdam as early consultants on the new Town Hall.26 That same year, Saenredam was at work on a painting of the interior of the Mariakerk in Utrecht, which, it has been argued, was commissioned by Huygens.27 Furthermore, the painter enjoyed a long relationship with his fellow Haarlemmer van Campen, dating back at least to 1628.28 It is thus possible that Saenredam knew of the imminent destruction of the old Town Hall from Huygens and van Campen and had been prompted by them to record it, either for a projected burgomasters’ chamber or, more generally, as a decorative piece for the planned building.29

Saenredam’s finished work may be situated in an older tradition of architectural paintings within Dutch churches and town halls, and this alone might suggest that he had originally intended it for the new Town Hall. Several examples of these largely anonymous late medieval architectural paintings are collected in a 1956 essay by G. Roosegaarde Bisschop.30 These works were often created as sciographic plans for churches or church towers, but the author demonstrates that the selfsame objects assumed different functions over time. Assessing their later uses, Bisschop groups a handful of the paintings under the rubric of remembrance. Among these are plans of Gothic churches that became memorial portraits after the depicted structures had burned. Bisschop cites two instances in which these pictures bear inscriptions that record the fires that destroyed their subjects—one of the church of St. Martin in Zaltbommel, whose tower burned in 1538; and another of the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft, struck by lightning in 1536.31 It is within this tradition that we may place the work by Saenredam.

The case of the Delft tower is of particular interest here. In his Beschryvinge der stadt Delft (Description of the city of Delft) (1667), Dirck van Bleyswijck reports how the painting was rescued from the city’s old Town Hall as it was razed by fire in 1618.32 He goes on to describe it as it then hung in the new Town Hall, completed in 1620 after a design by Hendrick de Keyser. While its frame features what van Bleyswijck calls an “archaic Low German rhyme” describing the disaster, which is still visible there in Gothic script, the painting bears the year 1620 at the bottom in a modern hand.33 As Bisschop argues, the date likely records the repainting of the fire-damaged work, which is in truth much older, before its move to the Aldermen’s Chamber in the new Town Hall.34 Perhaps at first a maquette, then a remembrance of the Nieuwe Kerk tower, the painting in its transference became a memorial of the old Town Hall itself. It established continuity between the medieval building and de Keyser’s classicist replacement, both as physical spolia and as the maintenance of a custom of remembrance present in the former Town Hall. In the salvage and translation of the relic the community rehearsed this custom of architectural memorial, arguably reenergizing it.

De Keyser’s Town Hall was the only large-scale classicist project of its kind in the Republic to precede Amsterdam’s planned new Town Hall. As such, the building and its decorative program would have been well known to van Campen and Huygens. Perhaps Saenredam took the Nieuwe Kerk tower painting as a precedent for his own work. The fire in Amsterdam’s old Town Hall was accidental and postdated Saenredam’s drawing, yet the artist chose to memorialize a building that he likely knew would be soon demolished. The later inscription about the fire is thus contiguous with what we might imagine as his initial intent. His painting not only depicts a medieval town hall but may also refer to a late medieval mode of remembering disappeared architecture, one that recalls the customs of the older town hall. While critiques of Amsterdam’s new Town Hall do not surface until 1643, two years after the drawing, Saenredam and his circle may have already been concerned with the loss of tradition that the building came to represent. As I will argue, the proposed sublime effect of Saenredam’s finished painting asserted identity between the old and new Town Halls, restoring the past at the administrative heart of the latter structure. We can only speculate, but this may constitute one of the earliest motives behind Saenredam’s initial drawing.

Vanity and Violation of Tradition in the New Town Hall

The most powerful critic of the new Town Hall was the strictly Calvinist William Backer, one of the four sitting burgomasters during the building’s planning phase in the 1640s. Internal debate over the great expense of the structure had arisen as early as January of 1643, but dissent was at its strongest after the adjacent Nieuwe Kerk burned in 1645.35 Backer took this opportunity to extract a concession from his more liberal counterparts in the city government. He demanded that a tower for the church should be built, one that would rise above the proposed height of its secular neighbor.36 When Backer died in 1652, however, construction on the tower’s base ceased.37 Nevertheless, as Eddy de Jongh argues, paintings and prints of the Dam with the tower shown in a state of completion were produced up until 1654, suggesting that there was sympathy for Backer’s cause among the public.38 Vondel’s poem on the ceremonial opening of the building, “Inauguration of the Town Hall of Amsterdam” (1655), indicates that these complaints were indeed widespread, as it is in part an argument against what it claims are accusations of worldly vanity against the new Town Hall.

In section fifteen of the poem, “Critique and Reply,” Vondel begins by formulating the reproach to the building’s alleged vanity in simple terms that recall the proverbial thrift of the Dutch: “Where has the saving nature of our Amstel people survived?”39 As the verses that follow make clear, this is a response to the demolition of the Gothic Town Hall. The critical voice tells how Evander, mythical founder of Rome, gave shelter to Aeneas and Hercules, though he lived in a modest herder’s shack. The parable argues that the old Town Hall was perfectly suited to its continued use, implying that the new Town Hall is excessive and wasteful. It characterizes the loss of the old building as a break in time, a fissure whereby the present is no longer guided by the values of the past. These accusations reach their height when the reproachful chorus turns to Amsterdam, exclaiming, “How this city, sprung from fishermen, forgets itself in such luxury, undesired by its ancestors! Happy is the city that knows its origins, [and] preserves a modest size.”40

This is the majority of the space that Vondel gives to the prosecution, unsurprising for the building’s advocate. What emerges in his text, however, is contiguous with the implied critique of Backer—that the new Town Hall’s worldly function did not warrant its opulence or a height that exceeded that of the church. What Vondel and Backer make clear is that the rapidly changing city inspired an anxiety in the public in which fear of impiety was bound up with a sense of loss of the past. These are the primary concerns, I will argue, to which Huygens and Saenredam responded. To properly understand this response, however, we must first understand the placement of the works within the burgomasters’ chamber.

The Site of The Old Town Hall and Huygen’s Dedication

As Jan Vos wrote of the burgomasters’ chamber, “the Town Hall is a ring, and this place the stone.”41 The metaphor suggests both the room’s prestige and its location as part of the projecting central portion of the facade, but also the jewel-like precision with which it was shaped. As Dapper tells us, The Old Town Hall was located to the left of the entrance to the proclamation gallery; it hung there first with Huygens’ dedicatory poem, facing the framed oath that the burgomasters took upon entering office.42 Later, perhaps in 1666, a copy of the dedication, cut in black marble with gilded letters, came to replace the oath, so that it faced the painting directly.43 The table at which the burgomasters conducted their business was located directly beneath this axis, the head burgomaster seated below the oath, facing the painting and dedication.

An illustration in an Italian topographical work on the Low Countries from 1690 makes the situation clear (fig. 4). It shows the interior of the chamber through the west door of the room, above which we see the relief of Mercury and Argus.44 Along the right interior wall, we see the four serving burgomasters seated at their table, one writing, one speaking, and the man against the wall reading. The dark framed surface marked by lines above the latter figure resembles the black tablet that bears Huygens’ text.

Unlike other parts of the new Town Hall, which had become a public tourist attraction, the burgomasters’ chamber was private, accessible only to the city’s four leaders. What thus distinguished Saenredam’s painting and the poem by Huygens from the rest of the building’s artworks was that they were not intended for public eyes; they had as their immediate audience the burgomasters themselves. The arrangement of the room suggests a pointed function to these elements by Huygens and Saenredam, that their content is directly addressed to the burgomasters. As I will demonstrate, the poem by Huygens was a rebuttal to the charge of idleness against the new Town Hall. Finally, I will argue that the sublime quality of Saenredam’s work acted as guarantor to the claims of Huygens’ dedication.

Huygens’ Dedication as Defense of the New Town Hall

The primary motive of the dedication is suggested by a letter to Huygens from his friend Jacob van der Burgh. The letter is dated January 19, 1657, nine days after the date given to the poem by Huygens. Van der Burgh reports that he has heard the dedication read aloud before the burgomasters, though he does not specify where or by whom. He relates his impression of it, however, saying, “I find the poem concise and after the scale of the largeness of the building; it rises above the eye of all critics and is deemed so perfect by the fitting judges, that the ornament of calligraphers could hardly contribute to its worth.”45 In drawing this analogy between building and poem, van der Burgh presents Huygens’ text as a defense of the new Town Hall, which, as we have seen, had suffered criticism for its size.

Huygens’ dedication is sixteen lines long, broken into two sections of four rhyming couplets:

Illustrious founders of the World’s Eighth Wonder,

Of so many stones above, upon so many piles under,

Of so much expense so artfully wrought,

Of so much luxury to so much use brought;

God, who gave you Reason to add to Power and Grandeur,

God sets you in this building with Reason and Pleasure,

To show who you are; and therein I enclose the universe,

Blessings be there ever in, and evil ever without.

Be it also fated, that these Marble walls,

Will not endure Earth’s extremities,

And if it becomes necessary that a Ninth appears,

To be the descendent of the Eighth Wonderwork;

God, thine Father God, God, thine Children’s Father,

God, so near to you, shall these Children be so nearer,

That their prosperity shall build and occupy another House,

To stand by the New, as the Old stood by it.46

The poem is structured according to the Vitruvian architectural virtues of beauty, usefulness, and durability, principles that guided Huygens and van Campen in their earlier collaborative building projects.47 In the first stanza, Huygens ties the building’s luxury—i.e., its beauty—to its use, which is equated with nothing less than the exercise of reason. It is with reason that God governs, as Huygens asserts in line six, and is also the faculty that He has granted the governors of Amsterdam as a means to manage the city’s wealth, the “Power and Grandeur” of line five. Reason is, furthermore, the guiding faculty of the master architect, as defined by Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture.48 It is expressed in the harmonious interrelationship of a building’s parts, a principle that surely dictated van Campen’s design of the new Town Hall.49 Thus, the granting of “Reason to add to Power and Grandeur” refers both to the wisdom with which the burgomasters manage the affairs of the city and to the expression of this wisdom in the architecture of the Town Hall itself. Huygens addresses those who would condemn what they saw as the building’s sacrilegious excess, arguing that its scale and expense mirror its high function. The new Town Hall is both “grand and concise,” to recall the words of van der Burgh, as it is the perfect outward expression of the godly office that occupies it.

It is to this sacred office and not the building itself that Huygens attributes the third Vitruvian quality of durability, an ironic reversal that rejects the charge of vanity against the building’s planners. The new Town Hall is in fact perishable, so Huygens tells us in the second stanza, but the successive burgomasters’ proximity to God guarantees an identity between the iterations of their home. This nearness to God of the city’s rulers, addressed in line fourteen, is arguably constituted by the resemblance asserted in the first stanza, a resemblance grounded in the reason with which God rules and has at once invested the sitting burgomasters. It is this same reason that will thus guide future burgomasters in the construction and disposal of yet another Town Hall, described in line fifteen, should the “Eighth Wonderwork” be destroyed.

Huygens’ second stanza argues that the godly wisdom of those who occupy the new Town Hall will not only survive but will increase with the following generations. In the final couplet, this argument for historical continuity is extended backward in time. Against the charge of an impious break with the past represented by the new Town Hall’s luxury and scale, Huygen’s last lines collapse the new Town Hall with the old Town Hall and the hypothetical “Ninth” wonder. Through a metaphor of spatial continuity, Huygens arguably implies a spiritual identity between the three buildings. That the reason possessed by the current and future burgomasters is that which guided their forebears in the old Town Hall is ultimately asserted by Huygens’ language itself. His description of the godly reason of the sitting burgomasters is borrowed from Jan Krul’s The Palace of the Amstel Gods (1636), a laudation to the burgomasters and their Gothic Town Hall. As I will now demonstrate, Saenredam, too, refers to Krul’s Palace, which was illustrated by an image of the old Town Hall. By making those virtues described in Krul’s poem present in the new Town Hall, The Old Town Hall guarantees the historical continuity argued for by Huygens.

The Sublime Effect of The Old Town Hall

To identify the sublimity of Saenredam’s The Old Town Hall, I draw on the definition of sublime effect in the visual arts as it is described by the painter’s contemporary and fellow Dutchman, the scholar Franciscus Junius. First issued in Latin in 1637 as De pictura veterum,50 Junius’s treatise on painting and poetry was commissioned by the author’s patron, Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, as a sort of critical companion to his well-known collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. An English translation was made by Junius himself for the benefit of the earl’s wife, Lady Alatheia Talbot, who did not read Latin.51 His Dutch translation appeared in 1641.52 Huygens, who was close to the court of Arundel, owned the 1638 English edition of the work,53 while Saenredam’s own library contained the expanded Dutch version, De schilder-konst der oude.54 An epigram for the frontispiece portrait of Junius in this edition was written by Vondel himself. It is thus possible that Saenredam was directly influenced by the work of Junius when he composed the preparatory drawing in July of 1641. Regardless, Junius’s ideas would have had wide circulation by 1658, whereby the privileged viewers of The Old Town Hall could have understood or experienced it in terms of the moral sublime.

The Painting of the Ancients is above all a response to the age-old condemnation of the sensual idleness of art, an accusation that Junius counters by urging artists to strive in their work for the morally uplifting. In defining this uplifting effect, he draws from Longinus’s Peri hypsous, which tells us that, “the true sublime naturally elevates us: uplifted with a sense of proud exaltation, we are filled with joy and pride, as if we ourselves had produced the very thing we heard.”55 Junius adapts this passage to the visual arts, saying,

Although now fairenesse of beautifull bodies doth very much take our minds, yet are wee more ravished by an accurate Imitation of this same beauty: for our thoughts cheered up and elevated by the contemplation of an absolute Imitation of perfect beautie, cannot containe themselves any longer, they doe leape as it were for joy, being extolled with the gallant bravery of what the eye beholdeth; not otherwise rejoicing in the good sucesse of Art, then if all we doe see were the work of our owne hands.56

The quote recalls Saenredam’s own claim to “accurate Imitation” in the inscription across the face of The Old Town Hall, namely that he “drew this first after life, with all its colors.” In Jacob van der Ulft’s copy of the work, made sometime after 1657, a similar inscription tells us that it was painted “na de levendige afbeeldinge” (after the lively—living, even—image).57 Van der Ulft omits Saenredam’s name, as if the virtuosity of the original performance had so fully effaced the creator that to copy the painting was to paint the old Town Hall directly from life. It is here then that we may begin to locate the sublime effect of the work, though the stirring of the audience with illusionistic presence through art was not an end in itself. Junius discourages artists from applying their imitative skill to “foolish and giddy-headed fancies,” urging them to undertake nobler conceptions—objects not merely of aesthetic but also moral loftiness.58

This moral dimension of the sublime is discussed by Longinus himself in Peri hypsous, though it has often been passed over by scholars interested only in the rhetorical value of the work. In the final chapter of the book, Longinus laments that “really sublime and transcendent natures are no longer, or only very rarely, now produced,” in his time.59 The cause, he tells us, is not oppressive government but the greed and self-interest of his contemporaries:

In close company with vast and unconscionable Wealth there follows, “step for step,” as they say, Extravagance: and no sooner has one opened the gates of cities or houses, than the other comes and makes a house there too. And when they have spent some time in our lives, philosophers tell us, they build a nest there and promptly set about begetting children; these are Swagger and Conceit and Luxury, no bastards but their trueborn issue.60

As I have shown above, Vondel suggests that a like complaint had accompanied the scale of the construction of the new Town Hall, namely that it opened the gates of Amsterdam to an era of decadence. It is fitting then that the sublime, through the agency of Saenredam’s work, should be employed to halt a descent into luxury at the heart of the symbol of Amsterdam’s new prosperity.

Toward the end of Book I of the Painting of the Ancients, Junius suggests the way in which lifelike representation in art may be used to uplift the spirits of the viewer in the context of civic architecture. Speaking of depictions of heroism and tragic events, Junius quotes the fourth-century Gallo-Roman orator Pacatus, who urges poets and painters to,

Let the market-places and the temples be graced with such sights, worke them out in ivorie, let them live in colours, let them stirre in brasse, let them augment the price of precious stone. It doth concerne the securitie of all the ages that such things might seeme to have been done; if by chance any one filled with unlawfull hopes might drinke in innocence by their eyes, when he shall see the monuments of these our times.61

The passage offers a striking parallel to the physical disposition of the burgomasters’ chamber, where Huygens’ poem and the work of Saenredam hung in tandem. The way in which the dedication emphasizes virtue in the form of reason has been established, but how was this effected through Saenredam’s work? Though the painter clearly strove to let the old Town Hall “live in colours,” the building appears almost in ruin.

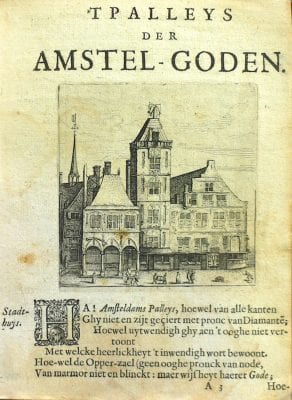

The composition of The Old Town Hall derives ultimately from Jan Claesz. Visscher’s print, a rough copy of which was used to illustrate Jan Krul’s ‘T Palleys der Amstel-Goden (The Palace of the Amstel Gods) (fig. 5). Saenredam’s painting may thus be seen as a visual allusion to the 1636 poem by Krul. Huygens’ own work is arguably indebted to it as well. The combined effect of the claim of Krul’s bold title—that the building beneath it could somehow constitute a palace—and the low quality of the engraving itself is that the old Town Hall appears even more meager than in Visscher’s original illustration, certainly more so than in the painting. The text beneath the image redeems it, however, emphasizing the spiritual riches behind its humble facade:

Ha! Amsterdam’s Palace, though you are not embellished on all sides with decorations of Diamonds; Though you do not show outwardly to the eye with what excellency your interior is occupied, How well that the upper room [the burgomaster’s chamber] . . . does not shine with marble, but with the wisdom of its Gods.62

The theme of the God-like elevation of Amsterdam’s leaders runs throughout the poem. The “upper-most Palace, called the Amstel Throne,” so Krul tells us, “is above all treasures embellished with knowledge, Wisdom depicted atop reason’s highest step, they [the burgomasters] sit there as Gods.”63 As Marijke Spies has demonstrated, it is from Krul that the descriptive tropes of subsequent poems on the new Town Hall descend.64 By equating the reason of the burgomasters with proximity to God, Huygens himself borrows the language of Krul, casting his subjects in the mold of their predecessors. This is not simply rhetorical dependence on poetic tradition, it is an argument for historical continuity, for identity between the old and new Town Halls.

Given the broad influence of Krul’s encomium, the burgomasters would likely have associated The Old Town Hall with the poem, aided by the memory of its accompanying illustration and the echo of its verses in Huygens’ text. If Saenredam’s vivid rendering thus restores the old Town Hall to life, it does so in a form conditioned by Krul’s images of the godly elevation of the former burgomasters. As Rixtel tells us, the effect of The Old Town Hall is that the burgomasters’ chamber “still draws glory from that old splendor,” what we may now equate with the reason of the city’s bygone leaders. Herein lies the true sublimity of Saenredam’s work, in its ability to move its audience by evoking the uplifting presence of an example of virtue. While the new Town Hall was critiqued as a violation of tradition in its expense, the sublime effect of The Old Town Hall ensured the survival of the reason that guided the old regime, a wisdom in governing that found its expression in the scale and disposition of the new building. In this way, Saenredam actualized the argument of Huygens.

In the Peri hypsous, Longinus describes “another road, besides those we have mentioned, which leads to sublimity . . . Zealous imitation of the great prose writers and poets of the past.”65 The passage that follows is quoted at length by Junius, extended of course to the domain of the visual arts. He says that,

Many are carried away by another mans spirit as by a divine inspiration, sayth [Longinus], even as the report goeth, that Pythia the Priest of Apollo is suddenly surprised when she approaches unto the trivet where they say there is an abrupt hole in the ground, breathing forth a divine exhalation; and that the priest filled with this divine power, doth instantly prophecie by inspiration. Even so do we see, that from the loftinesse of the Antients there doe flow some little streames into the minds of their imitators, so that they finde themselves to follow their greatnesse for company.66

What Junius posits is a model of divine transmission for the movement of sublime effect. Seated before Saenredam’s painting and the dedication by Huygens, the burgomasters were caught up as links in this chain of sublime transmission, stirred by the high virtue of their forebears. Engaged in the writing and debating that we see in the engraving of their chamber, the city leaders would have poured this sublimity into their own works. As the painting in Rixtel’s poem elevated the new Town Hall before its “old glory” and caused it to speak, the burgomasters themselves would have been moved at the sight of The Old Town Hall as they walked to the proclamation gallery. As their speech poured out of the mouth of the building, the people of Amsterdam too would have felt themselves lifted up. By evoking the wisdom of the former burgomasters within the new Town Hall, Saenredam ensured that the spirits of the city leaders matched the stunning rise of their new home. In doing so, arguably, he guaranteed the sublimity of the building itself.