The blocky brushwork and awkwardly positioned figure of Girl with a Flute (National Gallery of Art, Washington) have led many to doubt whether Johannes Vermeer, who painted the superficially similar Girl with the Red Hat (National Gallery of Art, Washington), also made this work. Over the last two years, curators, conservators, and scientists collaborated to resolve the uncertainty surrounding this painting and determined that the painting is not, in fact, by Vermeer. The artist who created this work was intimately familiar with Vermeer’s unique working methods and used the same materials and techniques but was unable to achieve Vermeer’s level of delicacy or expertise—raising the intriguing possibility that Vermeer had associates working with him in his studio. For further exploration, see “Methodology & Resources,” “First Steps in Vermeer’s Creative Process,” and “Experimentation and Innovation in Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat,” in this issue.

Introduction

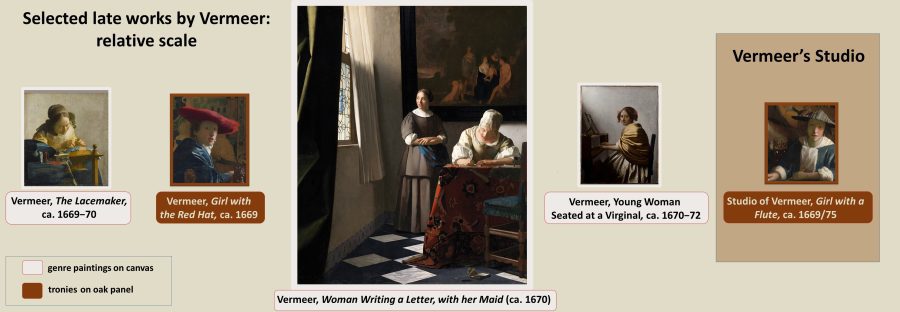

In the vast library of literature dedicated to Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), the question of whether he had a studio or workshop is rarely raised. Given the small size of his extant oeuvre—just thirty-five universally accepted paintings—most scholars have deemed the presence of students or followers unlikely and thus not worthy of debate: what artist would need help executing just one or two paintings per year? There are no surviving documents to suggest that Vermeer had a workshop—no records of pupils registered by the Delft painter’s guild, no mention of assistants in the notes of visitors to Vermeer’s studio—and yet we know that artists did not always formally register their assistants with the guild and that visitors did not always pay attention to anyone other than the main artist. The possible evidence for a studio, then, is best found in the artworks themselves. Thanks to a recent, in-depth technical and material study of the four paintings by and attributed to Vermeer at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, we see such evidence in the small tronie, Girl with a Flute (fig. 1).1

Pairing microanalysis of paint samples and magnified examination of the painting’s surface with a suite of non-invasive chemical imaging techniques, we have been able to identify the materials used in Girl with a Flute and better visualize and comprehend their application and distinctive handling in the context of unquestioned works by the artist. In comparing these elements, we see evidence of someone intimately familiar with Vermeer’s idiosyncratic working methods, of an artist who had the opportunity to observe Vermeer’s painting methods and determinedly mimicked his style but lacked the skill (and perhaps even the training) necessary to truly replicate his works. In these elements, we see evidence of a studio of Vermeer.

The form of this hypothetical studio remains unclear, but opening the possibility of its existence helps dismantle the long-standing and mythologizing assumption that Vermeer was an archetypal lone genius. Such assumptions are deeply embedded in the historiography of many early modern European artists, but for Vermeer, the elusive “Sphinx of Delft,” the idea is particularly difficult to shake.2 The 2017–2018 exhibition Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry unstitched the persistent notion of Vermeer as singular in his creativity by placing him within a milieu of frequent contact and active exchange among a select group of artists.3 This article similarly confronts the notion of Vermeer’s presumed solitude and posits him in the role of an instructor or mentor to the next generation of would-be artists.

Girl with a Flute in the Twentieth Century

The relationship between Vermeer and Girl with a Flute has long been a point of scholarly debate. Painted on a small wood panel measuring barely twenty by eighteen centimeters, it shows a woman seated before a patterned tapestry in a Spanish chair with lion’s-head finials, holding a recorder in her left hand. She wears a fur-trimmed jacket and a shallow conical hat that recalls Chinese examples made of woven bamboo, here modified by the addition of a gray, white, and black striped fabric covering. The formal similarities with Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat in the National Gallery (fig. 2)—which also features a young woman in a fanciful hat, a lion’s-head finial chair, and a tapestry backdrop—and the paintings’ nearly identical small sizes and atypical wood panel supports, have led many scholars to view the paintings as companion pieces and either accept or reject them as a pair. There is, however, no documentary evidence linking the two before they entered the collection of the National Gallery in 1942 and 1937, respectively.4 As we have discussed elsewhere in this volume, it is entirely possible that these are merely the only surviving examples of Vermeer’s small tronies on panel, a format that may have commanded more of his attention than we now recognize.5

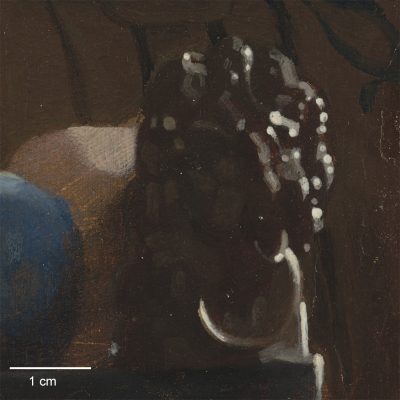

There is now scholarly consensus that Girl with the Red Hat is indeed by Vermeer,6 yet that same body of scholarship has not managed to resolve questions about the authorship of Girl with a Flute. For all its similarity to Girl with the Red Hat, Girl with a Flute displays clear compositional weaknesses: the figure is frontal, static; her arms and hands are awkwardly articulated; and we have only the vaguest sense of a body beneath her fur-trimmed robe. Rather than venturing an oblique glance from over her shoulder, the woman looks at us straight on. There is little attempt at intrigue or beguilement. Even the chair finial and background tapestry are awkwardly rendered—the brushwork is blocky and does little to create a sense of form or volume.

Despite these shortcomings, when the Girl with a Flute entered the National Gallery of Art in 1942 it was acclaimed as the museum’s fifth painting by Vermeer.7 The painting had been part of the collection of about six hundred paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts given to the museum by Joseph Widener from the collection he and his father P. A. B. Widener had amassed over some fifty years. Purchased in February 1923 from M. Knoedler & Co., New York, it was, according to the Paris art dealer René Gimpel, “truly one of the master’s most beautiful works.”8 A quarter-century later, however, scholars began to argue that Girl with a Flute could not have been painted by Vermeer, pointing to the painting’s relatively weak execution and particularly awkward passages (such as the hand holding the flute), which they viewed as unworthy of the master. Several even dismissed the work as a nineteenth-century imitation.9

In 1973–1974, a research team comprised of Arthur Wheelock Jr., then Finley Fellow at the National Gallery of Art, visiting Kress Professor and former Mauritshuis director Ary Bob de Vries, National Gallery paintings conservator Kay Silberfeld, and National Gallery technical advisor Robert Feller conducted a study that confirmed the painting’s materials are consistent with a seventeenth-century origin but concluded that the work belonged to the “circle of Vermeer.”10 Soon after, dendrochronology—a technique that can provide an earliest possible date for a work of art by examining the growth rings visible in the end grain of a wooden panel—determined a likely felling date between 1651 and 1661, confirming the panel’s seventeenth-century origins.11 In 1995, Wheelock (by then the National Gallery’s curator of northern Baroque paintings) revisited the attribution of this puzzling work, since, as it was believed, Vermeer did not have a “circle.” The question of what exactly constitutes a circle is a matter we will return to below, but by dropping this term Wheelock evidently meant that there was not a group of artists working in Vermeer’s immediate orbit—in effect, that he did not have a studio of assistants, acolytes, or collaborators. Instead, Wheelock argued that while the quality of Girl with a Flute’s execution was inferior to that of Girl with the Red Hat, removing it entirely from Vermeer’s oeuvre was too extreme, owing to “complex conservation issues.” He proposed that Vermeer initially blocked in the painting sometime in the mid-1660s and that another artist then revised it at later date. Based on this evaluation, the painting was re-catalogued as “attributed to Vermeer.”12

The complex conservation issues to which Wheelock referred include extensive areas of abrasion that exposed the underlayers, along with the appearance that the painting had been reworked while the initial composition was still largely at the blocking-in stage. However, some of the condition issues Wheelock described are in fact integral to the original paint structure: defects that resulted from the artist’s imperfect understanding of the materials. Our research has indeed identified alterations (described in further detail below), but where Wheelock took this as evidence of extensive revisions made to Vermeer’s initial composition by a later hand, we see an artist consistently and earnestly (if imperfectly) approximating Vermeer’s methods as well as his composition—quite likely inspired specifically by his Girl with the Red Hat. At all levels of execution, we see evidence of a single hand, following Vermeer’s manner and using equivalent materials and techniques, but unable to master his level of finesse or expertise. Whether that painter was merely inexperienced—for example, a young artist still learning the elements of the craft—or a painter, perhaps an amateur, who was simply less talented and less able than Vermeer, is difficult if not impossible to know. Nonetheless, our recent, in-depth technical research has enabled us to clarify the ways in which, the degree to which, and potentially the reasons why the two paintings differ.

Below the Surface

The research methods discussed in this study offer two avenues of approach: analysis at specific points on the paintings and across entire paintings. This is a brief overview of our methods (full details are found in Methodology & Resources). Further information can be found by clicking on the figures, which illustrate the main techniques used in this article.

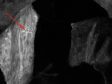

We gathered detailed information at specific points through microscopic analysis of a few paint samples: polarizing light microscopy (PLM) identified individual pigment particles in a few grains of paint (fig. 3); light microscopy of paint cross sections showed the layer structure (fig. 4); and analyzing those samples using scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) gave information on the pigments in each layer. It was also possible to infer pigment mixtures at specific points without taking samples using X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF)—which, like EDS, identifies chemical elements present—and reflectance spectroscopy collected with a fiber-optic probe (FORS), which gives information on molecular structure and color.

Chemical imaging performed across entire paintings offers a powerful way to visualize the distribution of painting materials, revealing aspects of Vermeer’s paint handling for specific parts of the composition. We inferred where pigments were used throughout the painting based on chemical elements detected with X-ray fluorescence imaging spectroscopy (XRF element mapping) (fig. 5) or identified pigments based on electronic transitions and molecular structure information obtained with reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS). In multispectral infrared reflectography (MS-IRR), three infrared images are combined in a false-color infrared reflectogram (IRR) that separates pigments more clearly than is possible with traditional infrared reflectography.

Finally, the information collected through these varied analytical methods was interpreted in the context of the painting itself, studied at high magnification. Because it is essential to compare paint handling at the same scale, scale bars indicate the magnification when this evidence is presented in close details and photomicrographs (fig. 6).

Support and Ground

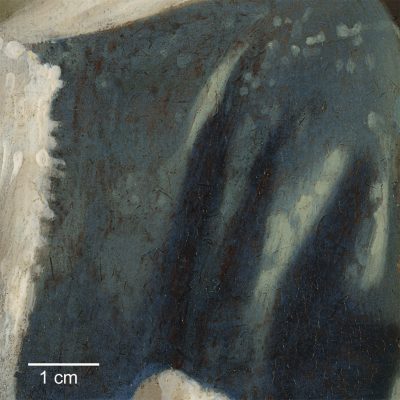

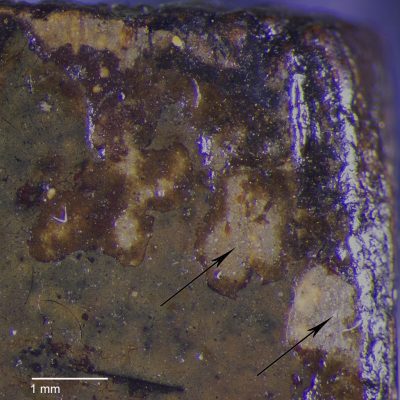

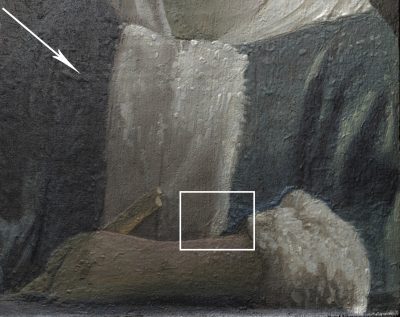

Girl with a Flute was painted on a single-plank oak panel in the standard Dutch seventeenth-century format, with a vertical grain and untrimmed beveled edges on the reverse, which show that the painting has not been cut down. Girl with the Red Hat also was painted on an oak panel, but in a taller format (the widths are comparable, but the height is almost three centimeters greater), making it unlikely that the two originated as a pair. We cannot make further direct comparisons between the two paintings’ supports, because early interventions have obscured the original panel structure of Girl with the Red Hat and blocked the use of dendrochronology.13 The panels of both paintings were prepared with a double ground: a lower chalk layer and a toned upper ground. However, the upper ground of Girl with a Flute is somewhat unusual. Unlike the ground of Girl with the Red Hat, where the panel was finished with a light tan upper ground over a chalk lower ground, the typical structure used on commercially prepared panels,14 the upper ground in Girl with a Flute is a coarsely ground, darker gray layer with a brushmarked texture (figs. 7, 8).15 While the standard ground offered high-life genre painters a smooth-surfaced starting point, a brushmarked ground would have interrupted the oak panel’s smooth surface and made it impossible to achieve the highly refined finish expected of their work. Technical examination of paintings from all phases of Vermeer’s work has not revealed such a rough ground surface in any other instance. This anomaly seems to imply that this panel’s ground was inexpertly prepared, perhaps even by an amateur.16

Preparatory Layers: Painted Sketch and Underpaint

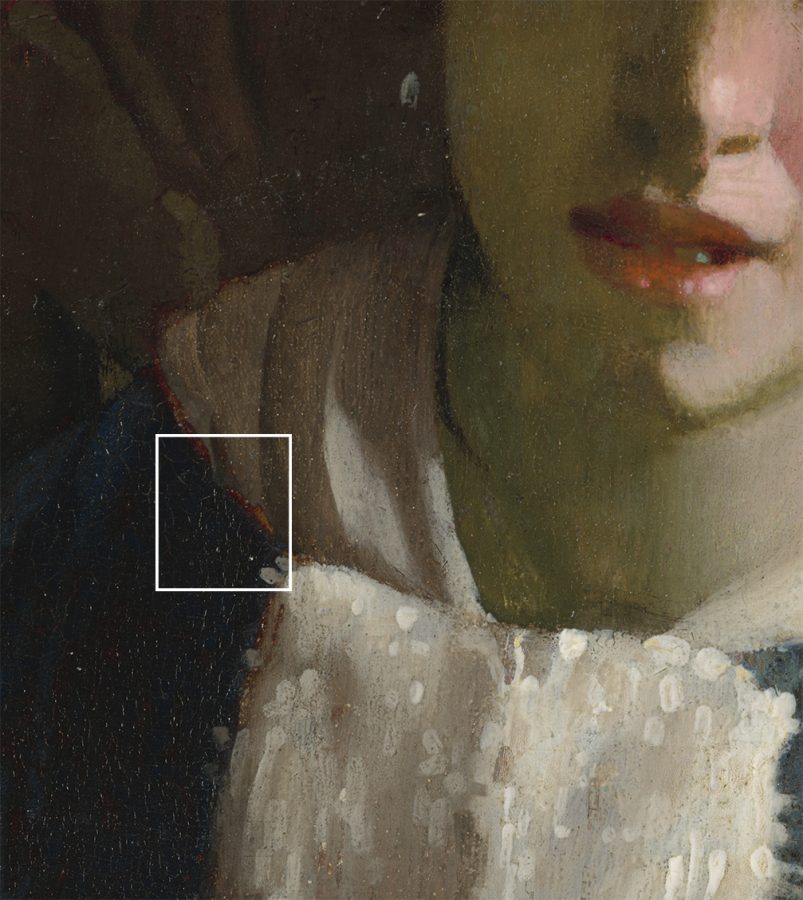

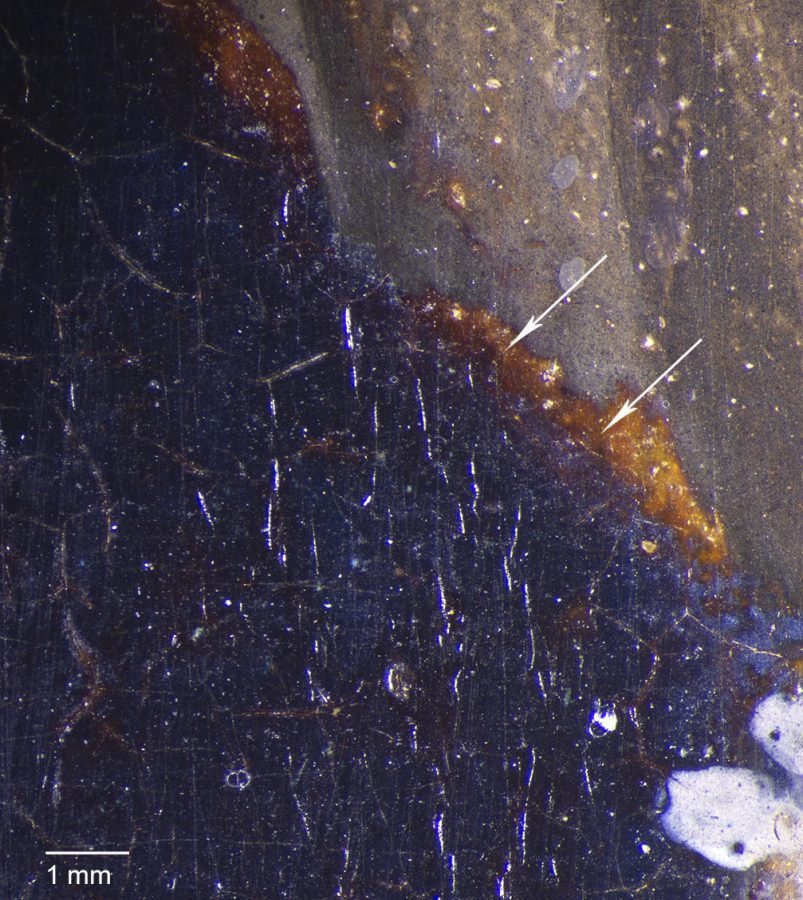

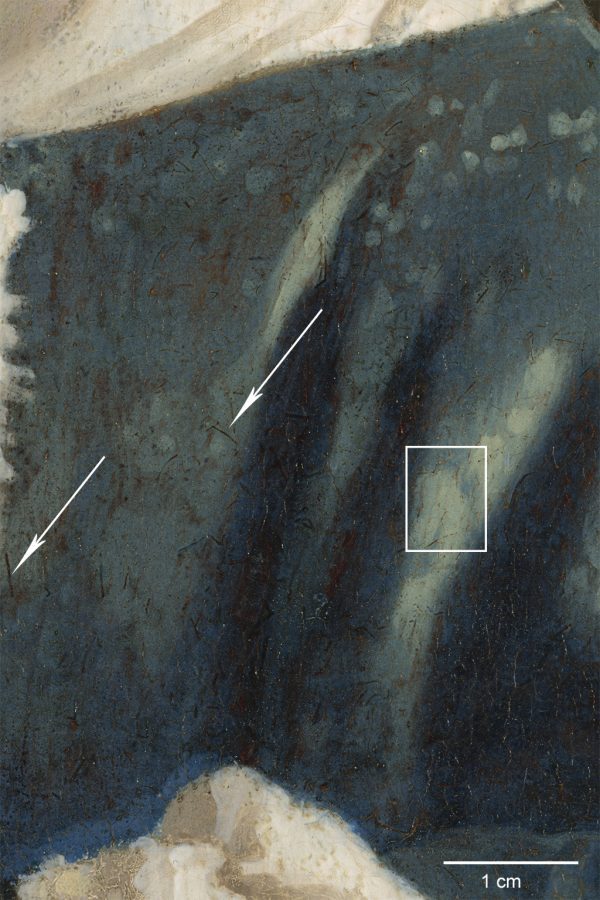

The preparatory layers of Girl with a Flute betray this artist’s general familiarity with Vermeer’s working methods but also reveal misunderstandings of his practice in the specific context of a tronie.17 Like Vermeer, this artist seems to have begun with a painted sketch in brown earth pigments to lay out both the design, using linear strokes, and the shadows, using broader washes of paint.18 As Vermeer did in both his genre paintings and tronies, this artist further established the forms in the underpaint stage and seems to have varied the color of the underpaint to some approximation of the final colors intended for various compositional elements.19 However, while the underpaint here, like Vermeer’s, is freely handled, it lacks that artist’s finesse. Thick pink strokes block out the face, and in the shadowed side of the jacket the translucent underpaint has a noticeably brushmarked texture that seems lumpy and clumsily applied, with arbitrary stokes that do not correspond to the jacket’s folds (fig. 9). Paint defects in the underlayers caused by poor painting technique may likewise betray an inexperienced (or unskilled) artist: magnified examination of the surface shows evidence of wide drying cracks in dark areas and wrinkles in white areas, where the artist scraped the surface to level it before applying the final paint, making revisions to the arm and flute (fig. 10).20 In the underpaint stage, the horizontal surface on which the figure rests her arm includes a broad swath of vermilion, and this reddish paint, which seems to have dried imperfectly, continued to ooze up through successive layers.21 Such severe paint defects are rarely observed in works by Vermeer.22

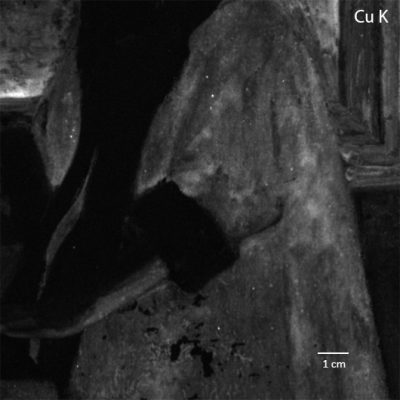

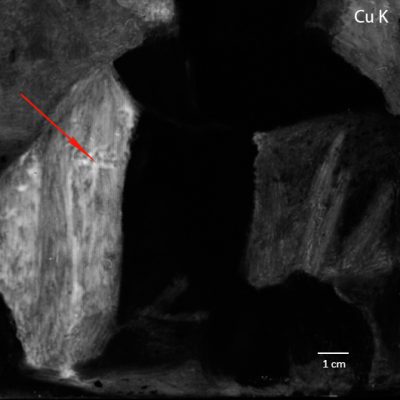

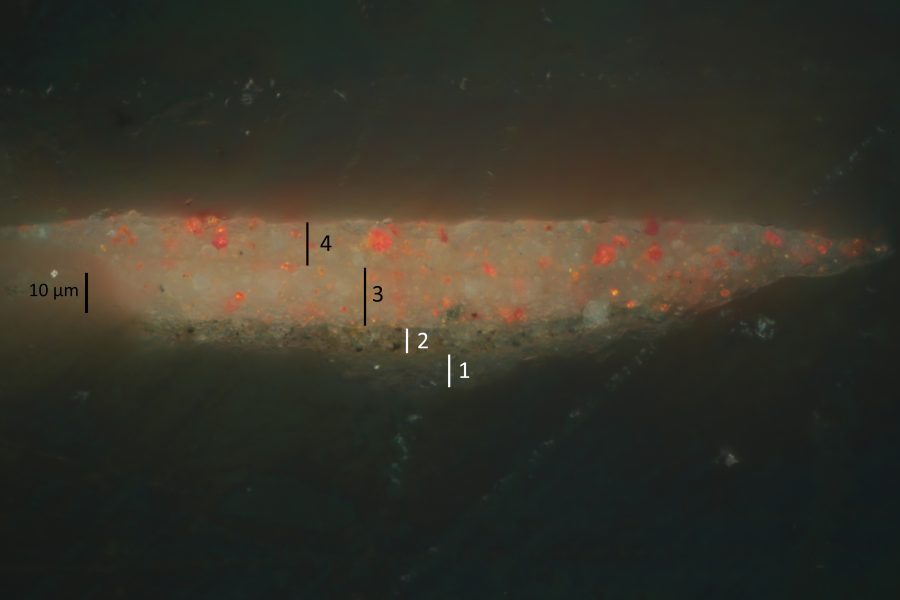

Based on our study of the National Gallery’s A Lady Writing (ca. 1665) and Woman Holding a Balance (ca. 1664), we suspect that in his genre works Vermeer added a copper-based drier such as verdigris in some areas of his underpaint to accelerate its drying.23 In some other paintings, Vermeer seems to have used verdigris as a pigment to create green areas of underpaint.24 It is not clear which of these practices the artist of this small tronie was emulating.25 However, their imitation of Vermeer did not successfully reproduce his methods; while they were aware of Vermeer’s general painting practices, they apparently misunderstood how best to execute an underpaint. The underpaint was found to be very brittle, a possible sign of paint degradation.26 In several areas the underpaint appears translucent and reddish-brown; however, microscopic paint analysis shows that the brownish underpaint of the jacket, sampled where it was exposed in the gap between the jacket and the kerchief (figs. 11, 12), also contains colored pigments, including ultramarine.27

Regardless of whether the underpaint of the jacket included verdigris as a green pigment or a drier, the XRF copper map—as in other works by Vermeer that we have examined—shows a distinctive pattern of brushwork that does not correspond to the final paint, offering evidence of the paint handling in the underpaint stage .28 This image presents an awkward contrast to Vermeer’s assured and quickly brushed technique, as seen in the underpaint of Woman Holding a Balance, for example. While the underpaint in both works generally built up the planned shadows in folds of fabric, Vermeer’s underpaint also quickly set the sleeve apart from the bodice and captured the weight of rounded folds with soft, fluid strokes (fig. 13). In Girl with a Flute, the artist indicated folds on the lighted side of the jacket with stiff lines of brushstrokes and underpainted the shadowed side by simply filling the area across the sleeve and bodice with dabbed strokes that made no attempt to model the forms (fig. 14).

Final Paint

Comparing the final painting stages of Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute reveals not only conceptual similarities but also evidence that an artist privy to idiosyncratic aspects of Vermeer’s painting process imitated his handling step-by-step. However, the tentative handling underscores the unknown artist’s inability to achieve Vermeer’s finesse despite emulating his procedures. Viewed with the naked eye, both faces are more abstractly rendered than those in Vermeer’s formal paintings, with stronger color contrasts. In each, the dull, greenish shadow that the broad hat casts over most of the face includes green earth, an unusual pigment choice for flesh tones in Dutch paintings. Vermeer repeatedly used green earth for flesh tone shadows later in his career, but this practice has not been observed elsewhere among high-life genre paintings by his peers.29 In both paintings, this greenish shadow is interrupted on one cheek by broad planes of bright pink highlight toned with vermilion (figs. 15, 16).30 The similarities extend to even minute details of brushwork: the lower lips of both tronies, for example, are highlighted with rounded pink-white dabs (lead white toned with traces of vermilion and black), layered wet into scarlet touches of vermilion. And in both paintings, the interior of the mouth is indicated with dark red lake, its color muted on the dark side of the mouth by a final thin application of green earth shadow (figs. 17, 18).31

Nevertheless, in every detail, Girl with a Flute lacks Vermeer’s refined paint handling. In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer sensitively modeled the broad, planar highlight on the cheek, shading the color below the eye and curving around the contours of the nose and mouth. By contrast, the painter of Girl with a Flute applied highlights on the cheek as hard-edged planes of thick, unvaried pink or gray paint. While Vermeer created a subtle greenish shadow in Girl with the Red Hat by modulating the color and feathering the edges, its echo in Girl with a Flute was painted—like the highlights—with a heavy-handed, flat application that pooled and almost dripped (figs. 19, 20).

In both Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute, the paint in the deepest shadows of the garments was thinly dragged, allowing the brown painted sketch to glimmer through (in the case of Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer exploited the brown sketch of the underlying unfinished painting). Highlights formed by mixtures of white lead and lead-tin yellow were touched onto the surface in dots and brushed along the folds in angular strokes. Yet in Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer created an abstract quality in the folds with a stark contrast between cool highlights—where he blended white lead into his paint—and isolated final strokes of almost pure lead-tin yellow. With a turn of the wrist, he varied the angle of his shorter strokes to imply a foliate pattern on the fabric. The jacket in Girl with a Flute is more simply modeled, with random dots of highlight and with the white and yellow pigments mixed throughout (figs. 21, 22).

This artist also misunderstood Vermeer’s practice of preparing his paints. Vermeer’s standard practice was to use coarsely ground pigments for his thickly brushed underpaint, but in the final paint he used more finely ground pigments to achieve his delicate handling.32 In A Lady Writing, for example, PLM analysis found that Vermeer used coarsely ground lead-tin yellow in the underpaint but ground the same pigment much more finely for his final paint. In the final paint of Girl with a Flute, however, the painter used lead-tin yellow ground as coarsely as the pigment in Vermeer’s underpaint.33 In some areas, the other artist inexplicably reversed Vermeer’s sequence: microscopic analysis of a paint cross section from a flesh tone shows pigments in the underpaint that are more finely ground than the final paint (fig. 23).34

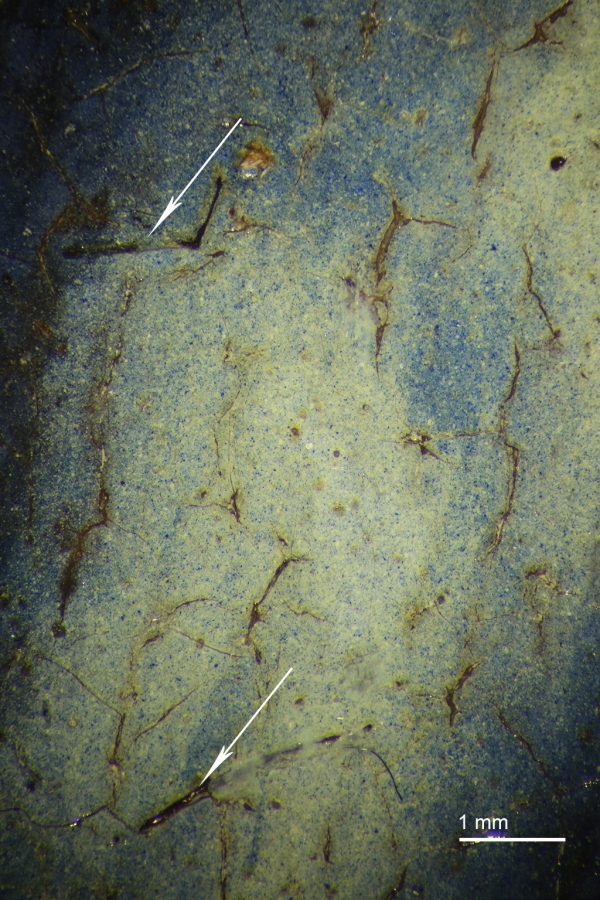

The pigments of the final paint, in fact, are often so coarsely ground that the surface has an almost granular character. Such coarsely ground paint must have been hard to handle, and the mass of broken bristles, loosed from the paint brush and embedded in the paint, hints that the painter may have used unusual force in applying the paint, as well as perhaps an old or poorly made brush (figs. 24, 25).35

Other discrepancies suggest that the artist of Girl with a Flute paid close attention to small details of Vermeer’s practice without always understanding the context. In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer portrayed the model’s glistening mouth and eyes with tiny dots of highlight that incorporate the color around them—faint pink (toned with vermilion) at the corner of the mouth and blue-green (toned with green earth) in the eye that looks out from the greenish shadow—in much the same way that he scattered matching spots of highlight in The Lacemaker: yellow on yellow carpet details, red on the cascade of red threads. The other artist, struck by this trademark detail, also added a dot of highlight but misunderstood Vermeer’s color harmonies, incongruously placing a blue-green dot within the pink mouth (see figs. 17, 18).

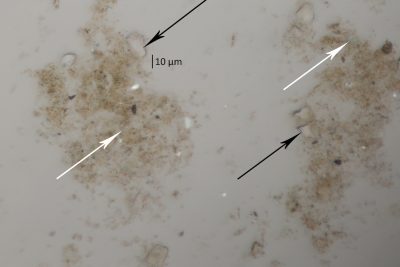

Another observation suggests that the painter of Girl with a Flute did not use the stock of supplies that was in Vermeer’s studio at the time he painted Girl with a Red Hat. Vermeer’s idiosyncratic use of green earth for shadows in flesh tones in his later works clearly made a strong impression on the other artist. But PLM analysis shows that where Vermeer mixed a deep blue-green version of green earth with yellow and brown earth pigments to delicately modulate the color of the shadowed flesh, the painter of Girl with a Flute used a paler green earth pigment with large glassy particles that were not observed in Girl with the Red Hat (figs. 26, 27).36 This discrepancy suggests that the two artists used different batches or grades of green earth, or even obtained their pigments from different sources.

From the earliest painting stages that show a rough upper ground layer and a lumpy, brushmarked texture in the underpaint, to the final steps that betray a struggle to apply coarsely ground paints and a reliance on hard-edged surfaces of thick, unvaried paint instead of planar highlights that sensitively curve along the forms, we can safely say that the creator of Girl with a Flute was no Vermeer. Indeed, the “natural experiment” of another artist attempting—with little success—to follow his lead, from compositional format to the smallest of technical details, only underscores Vermeer’s intuitive command of his own remarkable talents.

If Not Vermeer, Then Who?

At the National Gallery (as at many other museums), degrees of uncertainty around an artwork’s attribution fall into five major categories related to a named artist: “studio” or “workshop of,” “attributed to,” “follower of,” “circle of,” and “imitator” or “style of.” The distinctions between these groupings can be quite subtle, but they attempt to articulate the perceptible stylistic and qualitative differences in execution of works of art that seem not to be authored by the named artist. In the case of Girl with a Flute, the museum’s struggle to understand its attribution is reflected in the fact that, over the course of its eighty years in the National Gallery’s collection, it has borne nearly every one of these designations.

Perhaps the easiest to identify is “imitator or style of,” which denotes a stylistic relationship only, possibly vague, in which there need not be an implied chronological continuity of association. This designation might be used, for example, for an unknown nineteenth-century artist whose work resembles that of Vermeer or, in two cases at the National Gallery, forgeries: The Lacemaker and The Smiling Girl (figs. 28, 29). Likely painted in the 1920s by Theo van Wijngaarden (1874–1952), a Dutch painting restorer and occasional forger, the paintings combine elements from securely attributed compositions by Vermeer—the woman’s smile in The Smiling Girl was lifted from the woman in Couple with a Wine Glass (fig. 30), the Lacemaker’s pose from A Lady Writing (fig. 31)—and are executed with soft hues and specular highlights that, in the early twentieth century, felt representative of Vermeer’s style.37 The vague stylistic relationship, chronological discontinuity, and clear intention to deceive marks The Lacemaker and The Smiling Girl as pure forgeries, as they were definitively recognized in the 1974 study.38 Girl with a Flute, on the other hand, can be firmly dated to the seventeenth century thanks to dendrochronological analysis and bears a more substantive stylistic relationship to Vermeer’s extant oeuvre.

The designation “circle of” is used to point to an unidentified contemporary of the named artist, working in a similar style. For Vermeer, this term might be used for an unknown seventeenth-century artist whose work resembles his but who shows no signs of having worked directly with him. The research team investigating the National Gallery’s Vermeer holdings in the early 1970s concluded that Girl with a Flute belonged to the “circle of Vermeer,” but this nomenclature was subsequently changed, as per Wheelock’s argument that Vermeer did not actually have a “circle.” As noted above, by “circle” Wheelock seems to have meant something closer to a studio or workshop—in other words, people working with him. Today, the term “circle” is considered a bit old fashioned, as it implies a central artist around whom others orbited. Recent scholarship has framed the context of artistic production more accurately as a robust peer-to-peer network, rather than individual instances of an influencer and the influenced. As Eric Jan Sluijter and others have discussed, stylistic relationships were far more active and intentional than “circle” suggests. Artists were keenly attentive to each other’s work for purposes of imitation, emulation, and even rivalry.39 Indeed, many of Vermeer’s contemporaries, who seem never to have worked with him, quoted the visual qualities of his personal style in their own works.40

We might refer to them as a “circle” of appreciative peers. However, when we have studied the works of other artists who approximated Vermeer’s distinctive effects, we have found that they did so using their own accustomed painting practices, suggesting that they were familiar with his finished works but not necessarily privy to his studio practices.41 For example, in Geographers at Work (fig. 32), the Delft artist Cornelis de Man (1621–1706) painted the lion’s-head finials of a Spanish chair complete with circular highlights, a signature feature of Vermeer’s paintings. However, in incorporating this characteristic detail, De Man followed his own routine painting practice and not Vermeer’s: he systematically painted the finial in stages, along with the rest of the interior and furnishings, one color at a time. He adapted his standard practice with just a single, strategic touch, simulating but not replicating Vermeer’s characteristic wet-into-wet handling by simply using a dry brush to smudge a few of the yellowish mid-tones over the dried brown paint below (fig. 33).42

Girl with a Flute, on the other hand, presents a different situation. Here, the artist followed Vermeer’s process for crafting diffuse highlights, dutifully following Vermeer’s wet-into-wet process to suggest an abstracted play of light. Indeed, the painting processes are so similar that we can imagine this artist watched Vermeer paint. Yet the few curves and dashes of mid-tones, with which Vermeer magically conjured up the carved head of the chair’s finial in half-profile in Girl with the Red Hat (fig. 34), are in Girl with a Flute little more than patches of color on a poorly defined form (fig. 35). In contrast to the example of De Man, here we see an artist who understood the process but was unable to achieve the effect.

The designation “follower of” is used to indicate a closer proximity than “circle of.” It implies that the unidentified artist was working specifically in the style of the named artist, by whom they may or may not have been trained. Here chronological continuity, association, or a time limit of about a generation after the named artist’s death is implied. We are not presently aware of artists who might be considered “followers” of Vermeer, but examples of other seventeenth-century Dutch painters might be cited to clarify the appellation. Rembrandt inspired countless followers (who may or may not have been trained by him) who produced works in his manner: vigorously brushed, dramatically lit, and emotionally compelling. The prolific Jan van Goyen (1596–1656) inspired legions of routine landscape artists who adopted a superficially similar tonal landscape style.

At the National Gallery, “attributed to” is the standard nomenclature for a work with a degree of uncertainty surrounding the attribution to a named artist; the basis for the uncertainty may be stylistic or iconographic, but the physical condition of the work may also be a factor. As discussed above, in 1995 Wheelock classified Girl with a Flute as “attributed to Vermeer.” For Wheelock, both the stylistic and physical qualities of the painting raised doubts (although not enough to remove the work entirely from Vermeer’s oeuvre); he believed, moreover, that the underpainting revealed Vermeer’s hand. “Attributed to Vermeer” was thus felt to be the closest possible term to define the relationship between painter and painting.

There is only one painting currently “attributed to” Vermeer: Saint Praxedis (fig. 36) at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo. The subject, a second-century Roman saint collecting the blood of a decapitated martyr, was considered such a diversion from Vermeer’s known oeuvre that despite the signature “Meer 1655” in the lower right corner, it was not published as a Vermeer until 1986.43 Lingering doubts about the painting’s subject matter (atypical for Vermeer), and the fact that it is a nearly exact copy of a work by the Florentine painter Felice Ficherelli (1605–1660), has left Saint Praxedis in the limbo of “attributed to.” In this case, the uncertainty surrounding the attribution of the painting to the named artist lies in its stylistic and iconographic qualities. In the case of Girl with a Flute, on the other hand, the stylistic and formal elements are reasonably consistent with Vermeer’s oeuvre, and the artist must have been personally acquainted with his painting methods and materials. However, as we have argued, the inept execution and misunderstanding of materials do not reflect Vermeer’s confident and experienced approach to his craft.

Finally, there is the category of “studio or workshop of.” The National Gallery uses this designation to indicate that the painting was produced by students or assistants in the named artist’s workshop or studio, possibly with some participation or intervention by the master. A key determinant in this category is that the named artist originated the creative concept, and that the work was meant to leave the studio under his or her name.

The material and technical evidence that we have analyzed in Girl with a Flute tells us that whoever painted it had close access to Vermeer and his idiosyncratic working methods, just as a student or studio associate might. However, determining the precise nature of this hypothetical studio relationship is difficult, as no documents of any students survive (admittedly, the historical record is fragmentary at best, as registers of the servants or apprentices of guild masters in Vermeer’s hometown of Delft have disappeared).44 Most pupils or apprentices would have aspired to professional practice, but artists also took on well-to-do amateurs who desired only to learn the rudiments of drawing or painting to become more knowledgeable about the fine arts. As wealthy amateurs often paid higher fees than other pupils, this could be a worthwhile investment of time and effort. It may have been especially appealing for Vermeer, whom we know was experiencing financial difficulties in the economic downturn that coincided with the final years of his career.45

Contracts between a master painter and a would-be pupil often explicitly required that the master guide and instruct the pupil “without hiding anything from him”—i.e., share the studio “secrets” of his personal style and technique, including the preparation of pigments and paints.46 Yet the discrepancy between the handling of the pigments in Vermeer’s own work and in Girl with a Flute suggests that the artist of the latter picture could not have played a regular role in preparing Vermeer’s pigments and paints. An attentive assistant grinding pigments would surely have noticed that they were instructed to grind more coarsely when preparing paints for the underpaint stage and that Vermeer demanded more finely ground pigments as he painted the final image.47 And yet, the remarkable formal, technical, and material similarities between Girl with a Flute and Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat suggest that this unknown person was able to observe the artist at work in a close, student-like way, and was perhaps even responding directly to Girl with the Red Hat.

The phenomenon of closely related but not identical compositions produced by different hands recalls production in Rembrandt’s workshop, where the master’s paintings often served as prototypes for works by his students that could be sold under his name. His Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife in the Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (1655; inv. 828H) and the workshop version at the National Gallery (1655; inv. 1937.1.79) are good examples of this practice.48 Such “satellite” works follow a model of atelier practice dating back to the Renaissance, which distinguished between invention and execution. In this tradition, the master generated the creative concept for each piece (the “invention”), but the actual execution fell to an assistant trained in his style and technique. The assistant was expected to efface his own manner and ensure that the final composition looked as if it were produced by the master’s hand—the rationale being that a painting good enough to be approved by the master was as good as a painting actually by him.

Although it is difficult to imagine that Vermeer would have allowed a painting like Girl with a Flute—crafted by someone who could not master the nuances of his painting technique—to be sold under his name, it is possible that he took on a pupil or apprentice at some point in his career, perhaps as a source of much-needed income, agreeing to instruct an aspiring artist or amateur in exchange for tuition fees that might range between twenty and fifty guilders or more per year.49 As we have touched on in our discussion of Girl with the Red Hat, many considered the execution of tronies integral to a young artist’s training, as they encouraged careful attention to composition, character, and physiognomy; they were also a good way for young artists to begin to establish an identity in the market.50 Girl with a Flute may have been a workshop piece, a student exercise produced with Vermeer’s knowledge if not necessarily his imprimatur.

Apart from students and apprentices, it was also possible for an established artist like Vermeer to enlist the services of a journeyman painter—a trained but not yet independent artist—on an ad-hoc basis, a relationship that did not require registration with the guild.51 Although the practice does not appear to have been particularly widespread in the Dutch Republic, it offered artists (and here again we can consider Vermeer’s financial situation) a more cost-effective solution for occasional work than assuming the long-term commitment of training an apprentice.

Finally, we can consider that Vermeer’s family would have had opportunity to observe him closely while he worked. Scholars have periodically floated the notion of Vermeer family members working in his studio, though there is no archival evidence to indicate that any of his eleven children inherited their father’s artistic skills or pursued careers in the arts.52 Benjamin Binstock, one of the few writers to actively consider the existence and function of a Vermeer “studio,” proposed Maria, the eldest Vermeer child (1654–after 1713), as the artist responsible for eight stylistically and qualitatively disparate paintings he considers “misfit” Vermeers—including both Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute.53 Binstock further posited that after Vermeer’s death, several of these works were sold by Maria’s mother, Catherina van Bolnes (1631–1687), under her deceased husband’s name in order to meet the family’s financial obligations.54 While it is conceivable that Maria received instruction from her father and produced paintings in his manner while still in her late teens, prior to her marriage in 1674, the absence of proof to the contrary does not constitute support for Binstock’s provocative suggestion.

In sum, while we can resolve (and confidently reject) the theory that Girl with a Flute was begun by Vermeer, we simply cannot know who did paint the work, or under what circumstances—including whether the work was created in honest emulation or with the deliberate intent to fool a discerning seventeenth-century Dutch art market, as it certainly fooled connoisseurs in the early twentieth century.55

Conclusion

The body of new evidence we have assembled indicates that Vermeer was not involved in the creation of Girl with a Flute. The awkward composition and the unskilled paint handling are evidence of an artist who had not mastered their craft. Nevertheless, analysis of the painting materials and practices suggests this painter had an intimate knowledge of Vermeer’s working methods. It seems likely that the artist of Girl with a Flute was a contemporary of Vermeer who had a close relationship with him. The artist drew inspiration from his style and emulated his idiosyncratic working methods but lacked the skill required to replicate Vermeer’s masterful brushwork and subtle effects.

In the absence of critical documentary information, there are any number of possible scenarios that might explain the genesis of Girl with a Flute. Each theory is predicated on the evidence in the paintings by Vermeer that survive and cannot take into account all that might once have existed. In his later career, Vermeer turned increasingly toward producing variations on assuredly popular themes. Of the eleven paintings he produced between about 1666 and 1670, three were women writing letters with maids; three were women at a virginal; and two showed men of science deep in thought.56 We have noted that while Vermeer continued to paint large works like Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid (ca. 1670; National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin), he may also have pursued a more modest level of the art market with small, single-figured genre paintings like The Lacemaker (ca. 1669–70; Musée du Louvre) and Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (ca. 1670−72; The Leiden Collection), and we also have suggested that more tronies like Girl with the Red Hat once existed (fig. 37).57 Perhaps there were also more imitative tronies like Girl with a Flute, attempting to capture the appeal of a small but striking work by a famed artist like Vermeer. Removing Girl with a Flute from Vermeer’s oeuvre raises as many questions as it answers, but it also confirms that, for modern students and afficionados of Vermeer, there remain fresh avenues for exploration, data points yet to be found, and mysteries left to unravel.