Transcribed by Laura E. Antoniotti and Carol H. Kusinitz

Edited by Jacquelyn Coutré and Stephanie Dickey

The Foundation of a Library and a Fascination with Art

EGBERT: The library basically started with my interest in the history of art. I became interested in the history of art as a boy of twelve and then bought some books. I don’t think that any of those actually have been preserved.

But from the 1940s – by that time, I was seventeen, in 1940 – I bought some books. And I always put my signature and the date of the acquisition of every book. Sometimes I forgot, but as a rule I did so.

And so I have some books from 1941, ’42, about Dutch art. There is a book, for instance, which is called – which is about the Dutchness of Dutch art. So that was exactly something for a boy who wanted to know about art. And so I bought those things.

EIJK: If I may stop you for a moment. Your first book was bought around age twelve. So what led up to your motivation to buy a book about Dutch art at age twelve?

EGBERT: Actually, what led up to it was a friendship my parents had with a Dutch journalist, a radical socialist, actually, Henri, H-e-n-r-i, Wiessing. You may have heard his name. In the world of leftist people, communists and socialists, he was really very well known. He was the editor of De Groene Amsterdammer. And he was once visiting us in Heemstede. I think that was 1934.

EIJK: That’s where your parents lived?

EGBERT: … I lived with my parents in Heemstede. He visited us. And then he was going to go to an exhibition of Rodin at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Rondom Rodin it was called. Those were impressionist paintings and so on. He asked me whether I would join him, and I did. And I looked at the exhibition, and it kind of really interested me, it excited me.

EIJK: He took you with him?

EGBERT: He took me to the exhibition.

EIJK: … And so you walked around with him [Henri Wiessing] in the museum and talked about these statues –

EGBERT: Yes.

EIJK: — which had nothing to do with Dutch art. But what kind of conversation did you have with him, and what do you remember of that?

EGBERT: I don’t really remember. We just talked about – I remember I was very interested in a painting by – the French [painter] of beautiful girls.

EIJK: Oh. Um –

EGBERT: Renoir.

EIJK: Oh, Renoir.

EGBERT: There was in the exhibition a wonderful, wonderful portrait of a young girl.

EIJK: And at age twelve –

EGBERT: I never forgot that. So that was the memory that I took away from that exhibition. And I’ve always thought of it as a starting point. And then I bought some books from time to time.

EIJK: Did you go to the Rijksmuseum, for example?

EGBERT: I did go to the Rijksmuseum sometime, but … that [did not] interest me at first. …

EIJK: But living in Heemstede, your connection to the Rijksmuseum would be more distant, but to the Frans Hals Museum and the Teylers Museum, you might have –

EGBERT: I went there also. The Teylers Museum I was always interested in, partly because of the combination of industry, of machinery, of natural history, microscopes and all that, and art. It’s really unique. The Haarlem Teylers Museum is a unique institution that –

EIJK: Even today.

EGBERT: Even today – emphasizes God’s creation as far as manmade, both for society and industry and so on and for art. It’s really – the idea behind it, it’s really beautifully done. …

And so later on we moved to Haarlem, more to Haarlem itself, near the Hout, the house [where] we lived. … There I also, as a boy, I went to book dealers. De Vries was a book dealer in Haarlem. I think they still exist, De Vries, two words. There I bought just some general things on art. I didn’t really buy any books on literature or other things. I liked classical literature, Latin and Greek, at school, but the books that I bought were always books on art.

EIJK: And that’s because of the pictures?

EGBERT: And that was because of the pictures. Most people in Holland, growing up interested in art, they are interested in Dutch art because that was around.

EIJK: Yes.

EGBERT: So I was interested in Dutch art because it was around. …

EIJK: What were you attracted to?

EGBERT: 17th century. 17th century, just the general things, portraiture, landscape, Jacob [van] Ruisdael, Salomon Ruysdael, et cetera. That’s what interested me, and that’s what I bought.

EIJK: And these books you still have?

EGBERT: I still have, yes.

EIJK: So you never threw anything away?

EGBERT: I never threw anything away.

The Education of an Art Historian

EGBERT: We moved to Dordrecht because my sister, the elder one, … had a nice house and there was lots of space. It was practical and financially very good for my parents to join my sister. So we went there basically for personal reasons.

EIJK: So when you finished gymnasium – was it gymnasium alpha or beta?

EGBERT: Actually I took beta, because people told me that I was not good in languages. So I took beta. And then I had taken beta and passed it, of course, and then I wanted to do art history. But for art history at that time –

EIJK: You needed alpha.

EGBERT: — you had to do alpha. So I spent a year … I started art history in Utrecht and at the same time … did alpha with private tutors.

EIJK: So in 1943, you were boning up on the alpha part of the gymnasium –

EGBERT: … At the same time. … But in Utrecht I started with law.

EIJK: Oh, you started [with] law?

EGBERT: Yes, because –

EIJK: So you were interested in art history but –

EGBERT: I took law.

EIJK: — you chose law?

EGBERT: Because I found that, after all that had happened during the war, to do art history was not really the right thing to do. It was not realistic for society. It was not constructive in a positive way. It was –

EIJK: It was considered freeloading or –

EGBERT: Yes, or something.

EIJK: Is that the thought behind it, that it was not a productive profession?

EGBERT: It was not a productive area, yes.

EIJK: But that is typically Dutch, to have opinions like that. Instead of thinking, you know, you have to follow your heart and what you really desire to do, there are these influences.

EGBERT: I felt that I should do something for society, and I found that art history was not doing that. It was too – it had a certain elegance but also a certain superfluity.

So I went to law. And in the first law year … there’s mainly economics and Roman law. Those were the first fields that you had to cover.

And after doing half a year of Roman law and economics, I woke up in the morning and I realized, I told myself … that I could do something for society even with history of art.

EIJK: Ah. Self-serving discovery.

EGBERT: I discovered that I thought that if I tell people about art and try to make it understood and so on, that serves society in a different way.

So I went back to a teacher in history of art in Amsterdam by the name of [J.Q.] van Regteren Altena, and I told him that I was going to go back to the history of art. And he looked at me and said, “Egbert, I thought you would.” … I did that in Amsterdam.

EIJK: Amsterdam, okay. And that was the Gemeentelijk Universiteit.

EGBERT: Gemeentelijk Universiteit, not Vrije Universiteit ….

EIJK: That was the older university. …

EGBERT: When I was studying and I studied with van Regteren Altena –

EIJK: Yes. You had a good relationship with him?

EGBERT: I had a good relationship with him. And he was interested in drawings very much and he collected drawings, and so that’s where my interest in drawings originated. That was really very, very useful.

EIJK: Was there a good place to look at drawings? Where would you go to see drawings?

EGBERT: Well, we went to the Rijksmuseum. There were some drawings. I mean, there was not much at the time, but then Altena himself had drawings. He showed me some of his.

EIJK: So he collected –

EGBERT: He had a private collection.

EIJK: Is there a connection between him being a teacher but also a collector that caused you to think that you can be a teacher and a collector at the same time?

EGBERT: Absolutely. He did both, and that was his example for me. I never wanted to be a teacher only. I always wanted to do both. Or if I had to do one only, I would do the curatorship only, probably.

And with teaching, of course, I have been always interested in teaching with the originals, I mean, get people interested in the originals. …

… But my spending time – right after the war, with van Regteren Altena, as one of his students, I took a little job in the Institute of Fine Arts [of Amsterdam University]. … That was Herengracht 605. That was the Institute of History of Art.

And I offered myself as a voluntary worker, just to be involved in the history of art. … What I was asked to do was … [make] an index of festschriften.

EIJK: What?

EGBERT: Festschriften. That is a German word, of course, and those are basically publications by various authors made for scholars, particularly when they reach a certain age. Friends and colleagues, they produce a festschrift. And the institute, as a library, had a lot of festschriften. …

But I was asked, as a student, just to make an index of all the articles in a number of festschriften, because at that time there was no index, so you just had to know it. And there were no – there was no way to look it up. This was a very good idea.

EIJK: Because this actually nailed down some of the scholarly work –

EGBERT: Exactly.

EIJK: — and made it available.

EGBERT: Yes. Yes. And it was very good for me, because it got me into books and the whole idea of book cataloguing and all that. And at the same time, it got me in the Institute, where I was the assistant, always working with those festschriften.

And actually a student who also was studying there was Carlos van Hasselt. Carlos van Hasselt … later on became the curator of the Institut Neerlandais in Paris.

EIJK: In Paris.

EGBERT: I never realized that, but he always considered me his first teacher, because I was at the Institute, and I worked on those festschriften, and I made things accessible to him, both people accessible and books and so on accessible. He was very grateful to me.

A Passion for Drawings

EGBERT: … Van Hasselt was in drawings and I was in drawings, and that was because we both were interested in drawings because of van Regteren Altena. And Carlos van Hasselt was also a pupil of van Regteren Altena.

EIJK: Is there something that van Regteren Altena taught you about drawings that was important for your later focus? …

EGBERT: …the fact that I got interested in drawings and that I looked at the execution of drawing and how the black chalk was applied, so to say, the individual characteristics of an individual artist as characteristics of that work for identification of the works of art and so on, I did that.

And I remember at one point we suggested van Regteren Altena give a seminar on Venetian drawings and the influence of Venetian drawings in the Netherlands. It was a pretty good subject. …

EIJK: And it was because of Dutch artists traveling to [Italy] –

EGBERT: The drawings are so easy to – transmissible. I mean, the drawings are light. You can put them in your luggage or the donkey’s back or whatever. I mean, it is very easy. So it is a good means of transportation.

Furthermore, Holland was the first country where there was a real interest in drawings as a medium, to collect and to develop. Well, to develop perhaps is a little overstating it, but certainly to collect. Holland people collected drawings.

A Spanish Adventure…and an Opportunity

EIJK: After you were done with your studies in art history, did you do your thesis in Amsterdam?

EGBERT: Yes. Well, actually, when I had done the voluntary job in the Institute, I went to Spain to write a dissertation on the influence of Netherlandish artists, Dutch or Flemish, in Spain from the 14th to the 15th century, quite early – 14th through 16th century. Much too large a subject.

But anyhow, I mean, I really loved it. I went to Spain, and I spent more than half a year traveling everywhere, to the little villages where the paintings were and bronzes and so on. And I came back with an enormous amount of material.

And then I went to van Regteren Altena, who had to approve my dissertation, and I spent a day with him with photographs and documents and really an enormous amount of material. I spoke Spanish. I’ve lost most of it, but I really was fluent in it, and I loved Spain really.

And van Regteren Altena listened very carefully, and he seemed to be very interested, but he said, “Well, it’s very nice that you got all that material, but a dissertation it is not.”

EIJK: That was not encouraging.

EGBERT: You got it.

EIJK: That was a little deflating. Did he explain why?

EGBERT: It was not – it had no particular unity in it. It was too dispersed.

EIJK: So he wanted more focus.

EGBERT: It was not focused. So he wanted to have something special, but he didn’t give any indication as to how to focus it. …

By that time it was already 1950, and the Boijmans offered me a job, because the then director, [J.C.] Ebbinge Wubben, asked van Regteren Altena whether he had any student that he could recommend as a curator of drawings or a future curator of drawings. And [then] van Regeteren Altena said, “Sure, sure. Begemann.” So that was all I did for a job. Sorry to say –

EIJK: [No] job interview.

EGBERT: So that’s the way it was. So I went to Rotterdam and started there –

EIJK: As curator of –

EGBERT: — as an assistant curator of drawings.

EIJK: Of drawings.

EGBERT: And that was really wonderful, but –

EIJK: And they had many drawings there?

EGBERT: Yes. Thousands.

EIJK: Still do?

EGBERT: Still, and really excellent… people really recognize how good the collection is. … And it has most of the Koenigs Collection, Koenigs, the collector of drawings in Haarlem.

And I had a wonderful time. I got there in 1950 and was curator – assistant curator of drawings. But there was very – there was practically no staff and the director, Ebbinge Wubben, was also curator of paintings but had no time for the paintings. So I gradually became curator of paintings.

It was a wonderful time. I did everything…and we organized wonderful exhibitions. Those eight years – I’ll tell you what the end of the period is, but those eight years, I worked really absolutely like mad, day and night. But I learned the field. That is where I learned history of art, and that’s why I always say, university education is all very nice, but where you really become a professional is in the museum. …

And so I was in the Boijmans from 1950, and [curator of] drawings and paintings. I didn’t do the prints – we had a separate print curator there – although I was interested in them.

But then I met my future wife and we got married. We had three little children in Rotterdam.

A Fortuitous Meeting…and the Move to America

Then in 1956, I had a wonderful meeting with Erwin Panofsky. … Erwin Panofsky was one of the leading art historians in this country at the Institute for Advanced Study. …

And he was there just appointed to do work, to study, to be an intellectual art historian. And he did wonderful things. He wrote a book on early Netherlandish painting that still is superior. It’s really wonderful. …

But he came to Rotterdam in 1956 with his wife to visit a Rembrandt exhibition, and I had made that Rembrandt exhibition. I had selected the drawings, together with my director, and I had written the catalogue by myself, all of it, and that was a really wonderful experience.

And he came to see, and we looked with great interest and with much time at the whole exhibition. And then –

EIJK: This was on Rembrandt?

EGBERT: Rembrandt drawings.

EIJK: Drawings. Not prints nor etchings?

EGBERT: No, not – I mean, I was also curator of the painting exhibition, but at the time that he was in Rotterdam, we had the drawings, and Amsterdam Rijksmuseum had the paintings.

And we had a wonderful time there, we had a very nice lunch, and I talked with him and we kind of understood each other. He was retired, of course, and I was young, but this was a very nice acquaintance.

And so then when that was finished, he said, “You know, I have no influence at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, but if ever you want to come, write me a letter and I’ll see what I can do.” …

But anyhow, we decided to go to America. So I wrote a letter to Panofsky and initiated the application. There was no application. You had to be invited.

Anyhow, I was invited for half a year … and became a member at the Institute for Advanced Studies, which was really a great honor.

EIJK: Yes.

EGBERT: Particularly at that age. … This was in 1958. So I was 35.

And we came to America. And rather than go with the idea of coming back to Rotterdam, I gave up my job in Rotterdam, and we took all our furniture with us rather than just only some suitcases to return. …

And then I had luck at Harvard. The first year I went to Harvard, I filled in for Seymour Slive and for … Agnes Mongan. And I substituted for both of them half a year each.

So we went with those three children to Harvard, and I took care of the print room and the drawings and taught a class on early Netherlandish painting for Seymour Slive at Harvard.

And then in the course of the year, Yale needed somebody for a longer period of time … so I went to Yale. George Hamilton needed somebody in Italian Renaissance painting and came to Sydney Freedberg [at Harvard University]. Sydney said, “No, we don’t have anybody in Italian art. I’m terribly sorry. But up there in that little office in the attic there is Mr. Begemann from Rotterdam. Why don’t you ask him.” So he came up and we talked, and that’s the way I got to Yale. …

And so then I went to Yale, and at Yale again I wanted to join museum work [with] the university. … Yale happened to want to have a new curator of prints and drawings, because the lady that was doing [that] was running out of steam. … So I did that, and at the same time, I was teaching. By that time, I collected more books. … I should emphasize that, in my telling you about my various activities, drawings of course comes —

EIJK: First.

EGBERT: — first. But at the same time, I did a lot in painting, in teaching. I mean, it is my field. So even if my professional activity in the sense of my job that I had to carry out is drawings, I am very much interested in paintings, and that reflects itself in the library.

…

EIJK: So how did you go from Yale to this institution [the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University]?

EGBERT: Well, actually I’ll tell you. I was asked by the Institute in 1969 and I was offered a job here.

EIJK: The job was offered by the Institute, not by the university?

EGBERT: By the Institute. But of course that is in agreement with the university. …

I was offered a certain sum as income. And then we looked into the housing difference between housing in New Haven and housing close to New York, and it turned out that it was a tremendous step down, so I couldn’t do it. So I came back and I said, “I’m terribly sorry, but I can’t accept it,” and that was that. …

[I ended up coming here in…] December ’77, January ’78. … I then came to the Institute and offered myself. I said, “Look, I was here in ’69. You asked me to come. I couldn’t do it and I was sorry, but now I can do it.” So I was offered the job then for teaching. …

I was in a certain way happy to change – to get another institution to work for. I had been sixteen years at Yale, and in those sixteen years, I had learned the whole university. I knew the committees, I knew the people for appointment and all that, and I knew my colleagues, and everything was just –

EIJK: Old hat.

EGBERT: — old hat. Everything was repetition. And the Institute here has a greater link, a stronger tie, with the rest of the world. Yale and other universities are units by themselves but are not directly connected with the artistic activity [of] the world.

The Institute is very much – since it is in New York, it is very much in the center of the art world. Collectors are here or collectors come here, and that makes a tremendous difference.

A Thesis on Buytewech

EIJK: You did a doctoral thesis?

EGBERT: Yes, on Willem Buytewech. He did paint, and I also did his paintings.

EIJK: On Willem Buytewech?

EGBERT: Yes, in 19 – actually, we left – 1958 is the date.

EIJK: That’s when you came to –

EGBERT: Came to the United States.

EIJK: Yes.

EGBERT: Actually, we left in December ’58, and we arrived here in January ’59. But just a monograph it was on Willem Buytewech. … It was the whole – the life of – there’s a catalogue of the drawings.

EIJK: Was he mostly a [draftsman]? He was a sketcher?

EGBERT: Yes.

EIJK: Not a painter?

EGBERT: He was a painter also.

…

EIJK: [Why did you choose] Buytewech? Were you pushed by someone?

EGBERT: Well, actually, you know I told you about Spanish and the influence of Dutch and Flemish art in Spain. So at the time I got the job at the Boijmans in 1950, I needed still to write my dissertation. So I wanted to do that at the same time. And while I was working, that was – …

EIJK: You were working very hard.

EGBERT: Really very, very hard.

EIJK: Very productive period in your life.

…

EGBERT: Well, actually, when that Spanish project fell through, I needed another project, and then somebody told me that the previous director in the Boijmans Museum by the name of [Dirk] Hannema … had started a dissertation on Buytewech but didn’t finish it. And so I found out that he had not finished it and didn’t want to do it, so I just did it. I never used any material of his, but I wrote it instead of him. …

EIJK: Yes. And the research on [Buytewech], was there good material on him?

EGBERT: Well, he was a Rotterdam artist, which was very convenient, because I lived in Rotterdam and I worked in Rotterdam, and the archives … were in Rotterdam. And the Boijmans had a number of drawings by him and also prints. So it kind of fell into place. So that was the way it was. It was very useful to do that.

…

EIJK: Your mentors, who were your mentors? Van Regteren Altena was in there.

EGBERT: And the other one was Jan van Gelder. And interestingly enough, even though officially I was a student at Amsterdam University with van Regteren Altena, in fact I learned a lot from Jan van Gelder in Utrecht, and I found that I had benefited so much from his advice that I asked him to give me the degree in Utrecht.

EIJK: Oh, I see.

EGBERT: So it was up to me to solve that diplomatic riddle with van Regeteren Altena and Jan van Gelder. But I discussed it with van Regteren Altena and made a very friendly arrangement. This just was more in keeping with my personal interest and my affiliation with Utrecht. That was no problem.

Building the Library

[Editors’ Note: Every Begemann student has had the privilege of consulting one of the most comprehensive personal libraries on Dutch and Flemish art in existence. In this concluding excerpt, Egbert talks about some of the rare treasures he acquired after moving to America.]

EIJK: Yes. Now, of course you collected [books] year in, year out for how many years? 50, 60 years?

EGBERT: Well, I mean, I started books very early, as I said, … But the antiquarian books, in other words, the rare books, I started those only in the mid 60’s, comparatively late, and here in the United States. …

EIJK: So you had – how did you make choices?

EGBERT: If I found it interesting enough, I bought it. It was just a matter of whether it fitted in my – most what I call sources, all the art books in Dutch I have kept, and in German, you know, in German as well, early German books. …

One of them is a translation of … Virgil’s … Georgica and Bucolica, … translated by Karel van Mander and illustrated by Hendrik Goltzius.

EIJK: So it’s translated from Latin?

EGBERT: From Latin, yes. …

EIJK: So illustrated by Goltzius?

EGBERT: Yes. And that’s the remarkable thing of it, because they are very early woodcuts by Goltzius. So that is not a book on art history, but it is basically a literary book. It is text by Virgil and that type of thing.

I mean, I bought it because … it was rare – it was expensive; that was not the reason – and because it was illustrated by Goltzius. And one of my students wrote a dissertation on Goltzius’ woodcuts. … And so it had also – it rang a bell. It was interesting. I mean, that is a tiny little booklet and very nice little woodcuts in it. …

Another book that I just recently added … is a description of Amsterdam by Pontanus …, and it is a description of Amsterdam of 1614. That is a Dutch description of Amsterdam, illustrated with lots of engravings, and really fascinating because it has illustrations of Amsterdam. It has the old town hall, and it has the Beurs and so on. It has other buildings in Amsterdam. … And it shows Africa. It shows a map of Africa, and it shows the boats – sailboats in Africa, and it shows African people dressed as Africans.

EIJK: And that was because of the –

EGBERT: This was because of Amsterdam’s trade with Africa. … And also there is a map of Indonesia. And it is all Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Amsterdam … Africa and African natives, they were a part of the description of Amsterdam.

EIJK: Incredible.

EGBERT: It was really – I mean, I wanted to mention it, particularly since it is such a demonstration of the pride and the extension of the Dutch population by [travel]… This is 1614. But it is the Dutch translation of the original Latin edition, which is 1610, and I have them both. … The prints are the same, more or less [in both editions]… The 1614, first-rate impressions. …

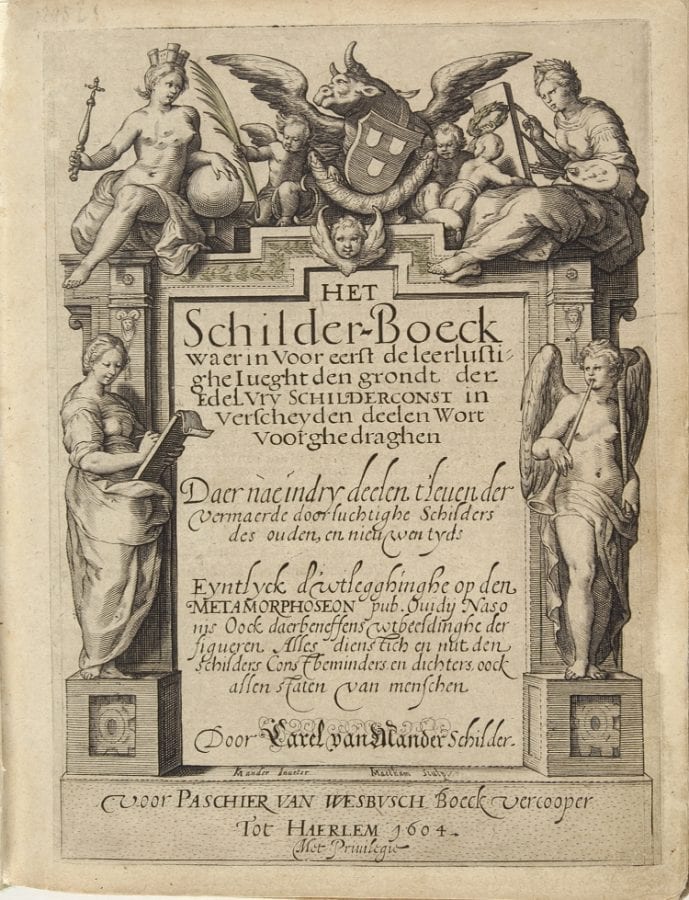

Another really great book, that is Karel van Mander … [Het] Schilder-Boeck. … I have three copies of it in the library. … two first editions, one extra illustrated … by the prints of Lampsonius. And there are about twelve prints, and they are portraits of Netherlandish, of Dutch, of Flemish, mainly Flemish 16th century artists. Vermeyen, Floris and so on. And they have been inserted in the book at the place where the text describes them. So when Karel van Mander comes to Vermeyen, then he puts the portrait [from] Lampsonius’ series in the book opposite the page that describes [Vermeyen]. …

1572 is the first edition of the prints, and they’re very rare. And the book – I saw the book at the book dealers and realized that these were the first edition of the prints, but the book dealer didn’t know what he had, so I got this for a decent price. …

Another book that I have is a translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a Dutch translation of 1657. That’s comparatively late, but the nice part of it is that it is just a book that was very popular for artists, because it has illustrations of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. …

So the book is 1657, a comparatively late edition, and not that rare … but in it, on the flyleaf … it says …”Bart — Barent Pietersz in de [Ryp] hoort dit boek toe.” In other words, Bart –

EIJK: He’s the owner.

EGBERT: … Now the situation is that Barent – Bart is [the painter] Barent Fabritius, who was a brother of Carel Fabritius, who lived in the [Ryp], the polder. He lived there, so he owned this book. … So … the fact that this is a popular handbook for artists, and you can imagine that Barent Fabritius … used it — I mean, that’s kind of fun.