One of the innovative elements in Franciscus Junius’s treatise The Painting of the Ancients (four editions, 1637–94) was the first discussion of Longinus’s concept of the sublime in the context of the figurative arts. Junius’s translation of his own treatise into English (1639) prepared the ground for the importance of the sublime in British aesthetics. Yet scrutiny of the underlying conceptions of The Painting of the Ancients reveals that his interpretation of this ancient concept was idiosyncratic. His interest in Longinus was not motivated by philosophy but rather by the painterly illusionism perfected in Netherlandish studios. This essay explores how Junius used the sublime to explain the “beholder’s share” in the artist’s evocation of a virtual reality. It points out the practical context in which his theory arose and how it relates to extant works, focusing on Rubens’s The Andrians and Rembrandt’s The Blinding of Samson.

That is great indeed . . . which doth still returne into our thoughts, which we can hardly or rather not at all put out of our minde, but the memorie of it sticketh close in us and will not be rubbed out: esteeme that also to be a most excellent and true magnificence, which is liked alwayes and by all men.1

This is Franciscus Junius’s definition of the sublime, the first time in the history of art theory that Longinus is quoted. Junius’s translation of his own treatise De pictura veterum (1637) into English (The Painting of the Ancients, 1639) prepared the ground for the importance of the sublime in British aesthetics. It may be evident, however, that his interpretation of Longinus was different from what happened among his later readers, from Dryden and Pope to, eventually, Burke.2 A specific Anglo-Dutch setting explains Junius’s interest in the concept of the sublime. Besides being known as an “extremely learned and famous”3 philologist in seventeenth-century England and Holland, Junius collaborated closely with a circle of artists around the Earl and Countess of Arundel in London. Not only did Arundel House hold the most important collection of ancient art north of the Alps, for which Junius acted as the curator. It was also inhabited by artists, most of whom were, like Junius himself, of overseas extraction: they apparently asked him to translate his book not only into English but also into Dutch (De schilderkonst der oude, 1641).4 His project joined the scholar’s study to the aristocrat’s collection and the artist’s workshop. His success in making ancient theories relevant for craftsmen seems to be evident from the fact that Longinus’s statement on the sublime was picked up thirty years later by Samuel van Hoogstraten, one of Rembrandt’s pupils.5

It is noteworthy, first of all, that Junius’s mention of Longinus signals a characteristic of his theory of art: he is the first to pay systematic attention to “the beholder’s share” in art theory. He uses a body of ancient literature, which had not been read by earlier authors, to make this possible. Longinus is, in fact, only a minor figure in his treatise, which draws particularly heavily on two other ancients, Philostratus the Elder and Philostratus the Younger (fig. 1). Junius made extensive notes to their work “when [he] was writing de Pictura veterum (in which treatise the elder and younger Philostratus are everie where quoted).”6 In order to locate Longinus in the larger framework of The Painting of the Ancients, it is the Philostrati who deserve our attention.

This article will explore Junius’s statement on the sublime in regard to the principles that guided his selection of ancient sources. The book is, after all, an attempt to reconstruct the ancients’ theory of painting that had not survived: “to collect the rules, which were, so to say, separated from their own corpus and scattered diffusely . . . and to arrange them in the frame of true art.”7

The following analysis begins with some general statements on the viewer’s reaction in seventeenth-century art theory that emphasize a generic lack of words (the aesthetic experience is apparently a pre-predicative one). Then, we will look more closely into the specific context that Junius provides for the sublime, connecting it closely to the faculty of the imagination: he differentiates the artistic imagination from the poetic one. The painterly imagination aims at the artist’s becoming present at the evoked scene, which is the only guarantee that the viewer may also become present at the same scene.

Ideally, this presence happens in a synaesthetic atmosphere involving all senses. Even more strongly, states Junius, painting is fully performative: looking at a painting means willingly or unwillingly acting out the evoked scene. The experience is corporeal rather than merely sensual. In the end, the painting leaves the viewer in physical pain. Is this the “true magnificence” of art?

Too Marvelous for Words

Junius’s treatise is the first in the tradition of art theory to give pride of place to the viewer’s reaction, which is construed as a—perhaps the—constitutive element of the artistic experience. He tried to be concrete about what earlier authors described in essentially vague terms.

When other seventeenth-century texts on painting describe the public’s reactions to works of art, these reactions often have little to do with assessments of stylistic qualities or choice of subject. They are generally phrased in terms of the viewer’s “astonishment” that “strikes him dumb.” A good example would be Annibale Caracci’s depiction of a scene from ancient literature: the Sleeping Venus based on Philostratus the Elder and Claudian (fig. 2).8 Giovanni Battista Agucchi saw this painting in 1602 and penned a reaction. His statement appears in the context of a discussion of the adequacy of language to describe visual impressions. Agucchi believed that ekphrasis is fundamentally inadequate: some works of art are “so perfect that the pen is powerless to describe them.”9 The description begins with set commonplaces: exclamations of desire to touch the painting on the one hand, and a professed reluctance to rouse the sleeping goddess on the other. The conflict this produces is characteristic of the state of confusion induced in the viewer, in which his sight and other senses are dazed. An impression unable to be evoked in words: “we can scarcely conjure up outstanding works of art in our mind, and we can certainly not express them with our weak faculty of intellect.” Agucchi concludes that his description is “as if . . . the paintings were covered by a coarse-grained veil, so that viewers can see them only with difficulty: these descriptions may be appreciated in a similar manner by the reader.”10 Just as a veil in front of a painting shields it from being seen completely, language intervenes between image and viewer.

In the Dutch literature, similar examples of this may be adduced from the concept of “astonishment” (verwondering) which cannot be further specified.11 Samuel van Hoogstraten describes reactions to paintings in terms of an ineffable experience: the viewer perspires profusely, finding himself embroiled in a “terrifyingly confused inner struggle.” Imbued with “a vivid sense of inexpressible joy,” he is so moved that he is almost incapable of averting his eyes from the work, and on his way home, his eyes are “drawn back to the memory of that rare sight.”12

Can we use Junius to give more shape to the disappointing, to art historians, formula of “inexpressible joy” as a reaction to a painting? Junius likewise refers to the viewer’s reaction to a work of art as an “incomprehensible pleasure”; the viewer is supposedly “speechless” or cast into a dream world. He describes how “great rings of amazed spectators together” are led “into an astonished extasie, their sense of seeing bereaving them of all other senses; which by a secret veneration maketh them stand tongue-tyed.”13 The moment of painterly evidentia clearly transcends rhetoric, and the reaction to it is therefore ineffable: “surpassing the power of speaking . . . uneasie also to them that are very eloquent . . . for every one of these things is apprehended by sense, and not by talke.”14 Apparently the significance of the visual arts lies precisely in their ability to appeal to this pre-predicative level of response. Seventeenth-century philosophy located this response not in the seat of the faculty of reason but in the “sensible” region of the imagination and the passions, which mediates between the physical and mental powers. Perhaps Simonides’s allusion to the art of painting as muta poesis can be construed in a positive sense. Paintings embody the rhetorical virtue of brevity in exemplary fashion: their “mute poetry” is so concise that they require no words at all.15 Junius writes of the effect of great works of art as transcending speech: “Incredible things finde no voice; . . . some things are greater, then that any mans discourse should be able to compasse them.”16

When silence may be construed as the most eloquent—or at least the most appropriate—reaction to a masterpiece, our analysis seems to halt. Yet when Junius takes care to separate poetic license from the visual imagination, it appears that there is more to say about the “beholder’s share” in the artistic experience.

Painting versus Poetry

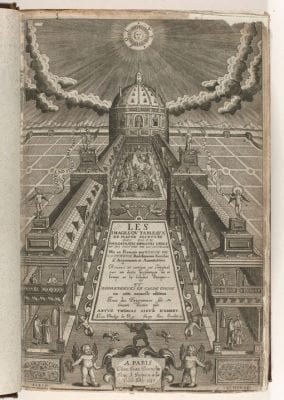

Let us first examine the context in which Junius quotes Longinus: a discussion of the imagination, the central concept in his treatise, which is depicted on the treatise’s title page according to Cesare Ripa’s precepts: a female figure with tiny figures coming out of her head (fig. 3). This context, given the modern conception of the sublime, seems logical, but a closer look reveals that Junius formulates a significant difference between the literary and the painterly powers of imagination:

Yet must not the Artificers here give too much scope to their own wittes, but make with Dionysius Longinus some difference between the Imaginations of Poets that doe intend onely “an astonished admiration,” and of Painters that have no other end but Perspicuitie . . . “[W]hat the Poets conceive, hath most commonly a more fabulous excellencie altogether surpassing the truth; but in the phantasies of Painters, nothing is so commendable as that there is both possibilitie and truth in them.”17

In painting, the products of the imagination are second to the artist’s striving for “evidence” or “perspicuity”: the ability of the artwork to virtually put things before the public’s eyes. The desired effect of astonishment is aroused by the work of art’s lifelike quality: viewers are struck by an “unspeakable admiration,” “beleeving that in these silent lineaments of members they doe see living and breathing bodies.”18 When Junius repeatedly states that his readers should train their imaginations, he is not trying to encourage developing a “great imagination” nor condoning trying out fantastic experiments. Although the capacity for forming strong mental images plays an essential role in his theory of art, Junius contends that it should be constrained in order to create convincing, lifelike pictures.

In Junius’s theory, the artist’s imagination is severely restricted: he holds the images originally provided by sense perception as the basis of all other deliberations. Approaching “life” means that the artist commits all his powers to conjuring up a virtual reality involving as many senses as possible—the better the sense input, the greater the beholder’s chance of effectively approaching the artist’s original mental image. The painter must, therefore, persuade his public that it is being confronted with reality and not fiction, by means of masterful trompe-l’oeil techniques, line, color, composition, and the rendering of emotions. Junius concludes, referring to Longinus: “Perspicuitie is the chiefest thing our Phantasie aimeth at,” and he explains how this rhetorical virtue subtly leads the spectator to experience forceful images and violent emotions by seductive skill instead of force:

that Art by the helpe of that same Perspicuitie doth seeme to obtaine easily of a man what shee forceth him to, and though shee doth ravish the minds and hearts of them that view her workes; yet doe they not feel themselves violently carried away, but thinke themselves gently led to the liking of what they see: . . . this is questionlesse that same Perspicuitie, the brood and only daughter of Phantasie . . . for whosoever meeteth with an evident and clear sight of things present, must needs bee mooved as with the presence of things.19

The theoretical pattern established by Junius requires a similar imaginative act on the part of the viewer. Junius, however, does notsay that the beholder should let the train of associations incited by the artwork inspire him to come up with his “own interpretation” or a purely subjective reaction. Rather, he should recreate the original reality that the artist had before him or conjured up before his mind’s eye. This is why being able to judge painting properly requires so much visual training and experience in forming mental images from sense impressions:

A sincere art-lover may store in his mind the living images of all kinds of things from nature, in order to compare them, when the moment is there, with the works of artists. Thus it is evident that one cannot effectuate this without the help of a strong imagination … “Fantasy,” says Michael Ephesius, “has been placed in our minds as a register or a record of what we have seen with our eyes or understood with our wits.” Thus also Apollonius Tyaneusmaintains that “those who intend to look at paintings in the right way, have need of a rare imaginative faculty.”20

What is revealing about Junius’s specific interpretation of his classical sources is that in this passage his “imaginative faculty” translates Philostratus’s term μιμετικη in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana.21 This seemingly minor change highlights a transformation that classical notions about the function of painting underwent before becoming part of Junius’s theory. The translation of mimesis as imagination shows how closely his concept of imagination is linked to the artist’s mimetic powers, the faithful representation of the visible world. Moreover, beholders need a strong imagination because they have to compare what they see in a painting to the stock of mental images of visible reality stored in their mind. The only guarantee that the viewer’s imagination can reconstruct the artist’s original mental image is the work’s lifelikeness or, in Junius’s words, an image’s “possibilitie and truth.”22

Becoming Present

Junius, in adapting classical rhetorical theory to the art of painting, not only equates the parts of an oration to five “parts of painting,” he also adds a sixth part: “a certaine kinde of Grace,” relating to the pleasing effect a painting makes on the viewer. This illustrates the shift of his focus with respect to that of his sources, which may explain his interest in Longinus. Junius completes the rhetorical framework with a theory of the affective response to images.23 On the one hand, such a shift in emphasis could be a result of the Arundels’ patronage: catering to the Earl and Countess’s implicit desires and elaborating a theory that championed the liefhebber’s learned eyes, Junius highlighted the beholder’s share as a constitutive element of the artistic experience. On the other hand, this new focus corresponded to certain transformations that had taken place in poetical and rhetorical theories in the Netherlands from the sixteenth century on. Broadly speaking, the ancient rhetoricians had developed ideas about every stage of the genesis of an oration, from the purely intellectual stage of inventio to the organization and ornamentation of the speech (the different partes orationis thus defined the chronological phases in the preparation of an address). In contrast, in the sixteenth and seventeenth-century Netherlands, emphasis fell on the stage of actio, the concrete interaction with the public itself, rather than on these preliminary steps. This had far-reaching consequences, for example in Dutch neo-Latin poetry.24 In antiquity, empathy with the protagonists in a narrative was seen as a prerogative of the poet. The Dutch author Janus Secundus redressed the balance: his poetical theory demanded a similar empathy with the narrative from the reader.

Junius’s treatise constitutes a key moment in this shift in focus from inventio to actio. To explore the theory of the “beholder’s share” in detail, he even introduced a new corpus of ancient texts into early modern art theory. This led to a Dutch revival of the ideas of the Second Sophistic, a school of philosophy and poetics from around AD 200. The writers of this period include Philostratus the Elder (ca. 170–244/249) and his grandson Philostratus the Younger (third century AD), Callistratus, and Lucian, in whose work ekphraseis, or descriptions of images, are crucial. The central text about the visual arts from this period, Philostratus the Elder’s Images (Eikones), appeared in several editions in the sixteenth century, in Latin and in the Italian and French vernaculars.25 The text describes a gallery with sixty-four paintings in Naples that may or may not have actually existed (fig. 4). Its detailed verbal imagery directly inspired various sixteenth-century artworks, the most remarkable of which were Titian’s Worship of Venus (1518–19) and Bacchanal of the Andrians (ca. 1523–25). (fig. 5–6) Surprisingly, however, the text had not been used by previous authors interested in reviving ancient painting in word and image from the fifteenth century on.26

Junius was the first author after antiquity to use the Images as the cornerstone of a consistent theory of painting. In a rare aside to his readers revealing his philological efforts, the scholar explained, seemingly to excuse his novel additions, that works by Philostratus and Callistratus were widely available at the time of writing: “everyone may obtain full disclosure on this matter because one can acquire their books everywhere.”27 Elsewhere, he was unambiguous about the importance of the Second Sophistic for his ideas on the beholder’s share: “The true way how to consider pictures and statues, is most plainly set downe in the books of Images made by the elder and younger Philostratus as also in Callistratus his Description of statues.”28 That Junius considered these authors essential to his project becomes especially clear from the fact that he collated a Greek Philostratus manuscript, borrowed from a colleague, together with his own sixteenth-century version in order to find the best readings.29 He apparently worked on a new edition, which, however, never materialized.30

As Junius was the first to use Philostratus the Elder and Younger so extensively, it is through his book that they became well-known figures in art theory. Bellori, for one, began his famous manifesto on “The Idea of Artists” with a passage from the Images, the first lines of which he derived directly from Junius.31 The question even arises whether there is any relationship between Rubens’s visit to London in 1629–30 and two paintings of scenes from the Images that he made around the same time or afterward, which emulated the two paintings by Titian mentioned above.32 Rubens painted these large works when he was in his fifties, late in his career, and they remained in his own collection.33 In the inventory of the artist’s possessions drawn up by his associates in 1640, they are not listed among the copies but as his own creations. Philostratus, and not Titian, is mentioned as a source.34 Junius may well have known the two Rubens paintings, which were of some repute in England; King Charles I himself considered buying them.35 What follows explores the hypothesis that Rubens’s interest in Philostratus was sparked by his confrontation with Junius’s ideas, even before their publication.36 Rubens visited the Arundel collections in 1629 and drew the ancient sculpture, concluding that he had “never seen anything in the world more rare.”37 It is likely that he spoke to Junius, the collection’s curator who was wont to explain it in learned terms to visitors.38 In any case, Rubens’s acquaintance with Junius’s ideas is testified to by his elaborate letter in praise of De pictura veterum, which was published in full in the Dutch translation. His enthusiasm about the book was only tempered by his desire for illustrations, examples to “point to with one’s fingers and say ‘here they are.’”39 His two paintings after Philostratus are visual confirmation of the statement penned in this letter, supplementing the Junian theory (fig. 7–8).

Junius combined ancient rhetorical vocabulary and the Philostrati’s ideas on evocative description to arrive at a coherent theory of artistic efficacy. As will be seen, this theory centers on the notion of empathy and conjoins the artist, artwork, and beholder in a single experience. One of Junius’s central ideas is that the beholder’s imagination takes the work of art as a starting point for constructing a mental image. Painterly elements, such as pigments and brushwork, line and color, fade away to make place for an illusion that also involves other senses than sight alone. Although Junius describes the construction of this mental image as a process prompted by the beholder’s affective response to the artwork, he does not use a term like “empathy,” deploying instead the concept of “presence” or, in Dutch, teghenwoordigheydt. This term merits some attention in the context of Junius’s attempt to reconstruct the ancient rules of painting, and to finally “arrange them in the frame of true art.”40

The Artist’s Presence

Junius’s term teghenwoordigheydt—a neologism no longer in use in modern Dutch—translates as the Latin praesentia and the English presence or performance.41 The Painting of the Ancients uses this word in at least three meanings. It refers to the physical presence of the artist in his work and that of the viewer in the depicted scene, as well as to the viewer’s mind becoming involved in a story through confrontation with a dramatic moment in a narrative timeline. Furthermore, echoes of teghenwoordigheydt as referring to a kind of transubstantiation also resonate: the word becoming flesh, or fiction becoming reality.42 This means that Junius deploys the term on various levels for his theory of painting. It returns in his analyses of art’s historical development; artistic invention; the making process; the art object itself; and finally the work’s effect on its public. The power of painting is to “make present” absent figures, such as the deceased, figures of the imagination, or the pagan gods. Junius states that poets manage to evoke the teghenwoordigheydt of the deities.43 Here, the term is literally translated from the Latin praesentia;44 the statement comes from Philostratus the Younger’s foreword to his book Images.45

For the Dutch scholar, presence is first of all defined as a function of the imagination. This faculty may replace absence with presence: “Phantasie doth so represent unto our mind the images of things absent, as if we had them at hand, and saw them before our eyes.”46 Even more essential than this statement about making the absent present, which could be found in Alberti, is Junius’s notion of “seeing something in the mind as if it were present” (als teghenwoordigh aenschouwen) in the context of rhetorical theory.47 This theory held that the orator should use metaphors and imaginative language such that, in Quintilian’s words, “the images of absent things are presented to the mind in such a way that we believe we are seeing these things with our own eyes and that we are present with them.”48 Teghenwoordigheydt refers more exclusively than the Latin term praesentia to the artistic and rhetorical ideal that the public should see a scene “happening before their very eyes,” to quote Cicero.49 This means that the painter or orator has to present a story as though he had been an eyewitness. Junius states that before putting brush to panel, the artist needs to evoke the scene he wants to depict in his mind’s eye as a narrative acted out in front of him:

Painters in like manner [as orators] doe fall to their worke invited and drawne on by the tickling pleasure of their nimble Imaginations . . . they doe first of all passe over every circumstance of the matter in hand, considering it seriously, as if they were present at the doing, or saw it acted before their eyes: whereupon feeling themselves well filled with a quick and lively imagination of the whole worke, they make haste to ease their overcharged braines by a speedie pourtraying of the conceit.50

It should be noted that one of Junius’s English readers, William Sanderson (ca. 1586–1676), identified this manner of working as being Rubens’s method: the artist “usually would (with his arms a cross) sit musing upon his work for some time; and in an instant in the livelinesse of spirit, with a nimble hand would force out, his over-charged brain into description . . . by a violent driving on of the passion.”51 Junius himself may have been thinking of Rubens when, in the context of this exercise of the mind’s eye, he lavished attention on Ovid’s account of Phaeton’s fall from his father’s carriage. This had only been possible because Ovid first “made himself present” in the narrative. Junius quotes Longinus verbatim:

would you not thinke then that the Poet stepping with Phaeton upon the waggon hath noted from the beginning to the end every particular accident . . . ? neither could he ever have conceived the least shadow of this dangerous enterprise, if he had not been as if it were present with the unfortunate youth.52

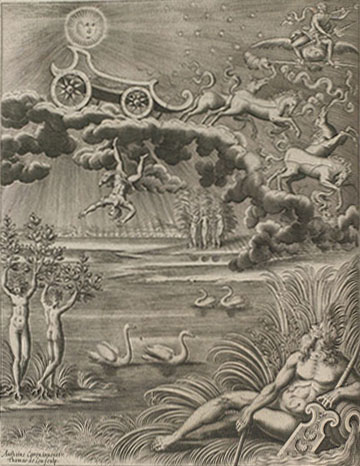

Exploring virtual presence, Junius even coins a neologistic verb, not in use in modern Dutch, sich verteghenwoordighen, making oneself present. More literally than the English text, this term suggests that it takes a creative effort on the part of the artist to become an eyewitness, or even an actor, in the narrative.53 The author must have been familiar with depictions of the theme in seventeenth-century art; his patroness Lady Arundel even had a ceiling painting representing Phaeton.54 A drawing by Goltzius circulated in print; Rubens’s work, painted in Italy around 1604–5 was in an Antwerp collection at the time (fig. 9–10). In effect, the master may have been drawn to the theme through the Philostratean theory rediscovered by Junius, who describes “unbridled horses with their tossed and tottered waggons” as a vision of the poetic imagination, a challenge hardly to be captured in paint (fig. 11).55 However, only a collaboration between Rubens and van Dyck (1636–38) bringing the theme closer to the foreground in visual terms, may be interpreted as an exploration of the idea that the artist had imagined himself present in Phaeton’s carriage (fig. 12).56

This mental presence is closely linked to the artist’s capacity to feel and recognize emotions. To Junius, imagining the presence of the figures in the narrative is connected to a satisfactory representation of emotions (“Affections and Passions”): “It is then in vaine an Artificer should hope to be both powerfull and perspicuous, unlesse he doe alwayes propound unto himselfe the worke in hand as if all were present [italics mine, TW].”57 In effect, he follows rhetorical theory directly in stating that, to move his public, the artist himself must first feel the emotions he wishes to evoke. It is:

a maine point, to have a true feeling of [the passions], rightly to conceive the true images of things, and to be mooved with them, as if they were rather true then [sic] imagined . . . and it standeth an Artificer upon it, rather to trie all what may be tried, then to marre the vigorous force of a fresh and warme Imagination by a slow and coole manner of Imitation[italics mine, TW].58

A striking feature of the Dutch reception of Junius’s theory is that his followers interpreted literally rather than figuratively his exhortation that whoever wanted to move his audience with feigned feelings should himself first experience real affliction. Van Hoogstraten, for instance, advises the painter to look in the mirror to discover how to represent the motions of the mind:

If one wants to gain honor in this noblest area of art, one must transform oneself wholly into an actor. It is not enough to show [emotions] weakly in a History; Demosthenes was no less learned than others when the people turned their backs on him in disgust: but after Satyrus had recited verses by Euripides and Sophocles to him with better diction and more graceful movements, and he had learnt . . . to mimic the actor precisely, after that, I say, people listened to him as an oracle of rhetoric. You will derive the same benefit from acting out the passions you have in mind, chiefly in front of a mirror, so as to be actor and spectator at the same time.59

Within the larger context of Dutch art, Junius’s statements are in keeping with the way some masters stressed the importance of their own “presence” in the depicted scene, as eyewitnesses they had greater persuasive force. Rembrandt, for example, wrote to Constantijn Huygens, the stadtholder’s artistic agent, that he had observed “the greatest [emotional] movement” in his Passion Series made for the princely patron. In these works he included himself twice, not only as a spectator, but even as an actor in the narrative of the Raising of the Cross and the Deposition (fig. 13–14).60 We should note that Huygens, who had visited the Arundel collection in 1618 and owned a copy of De pictura veterum, may have introduced Rembrandt to the Junian theory even before the publication of the Dutch edition.61

In relation to the stage of artistic invention, Junius also uses teghenwoordigheydt to instruct the artist to imagine that he is working in the presence of great predecessors and is subject to their judgment. The best results are achieved when the artist is in the “conceived presence of antient [sic], and the true presence of moderne masters.”62 For Junius, the fact that the painting of antiquity has not survived was an additional incentive to exercise one’s imagination. The concept of teghenwoordigheyd, thus, captures his book’s primary appeal, namely to make antiquity present, not through archeological study but through artistic imagination. Junius’s approach was eventually voiced in the Frisian painter Wybrand de Geest’s The Cabinet of Statues (1702), a treatise with illustrations of ancient statues in Rome, in which is stated “artists do not die… they live in the minds of men.”63

The Beholder’s Presence

Junius cites ancient authors who may “informe [the reader’s] judgment in the right manner of examining workes of Art” to elaborate his idea that not only artists but also their viewers should become virtually present in the imagined narrative. He refers approvingly to Claudian (ca. AD 370–404), who addresses the readers of a scene with people frightened by an erupting volcano as follows: “Doe not you see how the old man pointeth to the fire?”64 Here, the reader is invited to virtually join the protagonists and see what they see. Most frequently, however, Junius refers to authors from the Second Sophistic. He explains how before looking at a painting of distant islands, Philostratus the Elder urges his listeners to first imagine that they are on a ship and that their surroundings have changed into a sea (fig. 15):

Philostratus, a man exceeding well skilled in these things, taketh the spectator along with himselfe a ship boord, willeth him forget the shore and view every one of the represented circumstances as out of a ship; esteeming that his mind could not apprehend the severall parts of the picture rightly, unlesse with an imaginary presence it should first saile about, conferring the fresh and newly conceived Images with the picture it selfe.65

The viewer should direct his mind to his own “imaginary presence” to become fully part of the story (and here the Dutch states “als van het schipboord teghenwoordighlick te aenschouwen” [to behold as if one were present on board]). The quotation clarifies that not just the physical eyes are involved in the artistic experience but also the mind’s eye. This is in line with the Philostratean theory of ekphrasis, which assumes that a work of art is fundamentally incomplete. Supposedly, the artist records a mental image in the work of art, which must be conjured up by means of an imaginative effort on the part of the viewer.

The work of art acts as a stimulus for the imagination. Aspects of the painter’s craft, especially color, are secondary; when the original mental image is evoked again, the work of art itself—as no more than a medium—effectively fades away. To illustrate this, Junius draws attention to a passage from the Life of Apollonius of Tyana (2.22), in which Philostratus explains that it is possible to draw a black man without actually making the skin color dark; the painter can rely on his evocative powers to suggest the hue.66 In Junius’s response theory, aspects of craftsmanship, such as color, are secondary. All that counts is that the artwork stimulates the imagination and activates a chain of associations: the viewer’s experience of a painting becomes an immersion in a virtual reality. As we shall see, moreover, not only sight but also the other senses are deemed to be affected by the reality evoked in the painting. These notions suggest that the viewer’s reaction must fulfill the role of a necessary complement, for the virtual reality of the artistic moment to take effect.

In even stronger terms, Junius explains that looking at a work of art is ideally a performative act, in which the moment of seeing turns into virtually being present in the narrative or even becoming an agent in it. Seeing becomes experiencing:

This ought therefore to be our chiefest care, that wee should not onely goe with our eyes over the severall figures represented by the worke, but that we should likewise suffer our mind to enter into a lively consideration of what wee see expressed; not otherwise then if wee were present, and saw not the counterfeited image but the reall performance of the thing [italics mine, TW].67

Even in the context of landscape painting, Junius inserts long passages on how a liefhebber contemplates various elements in a landscape: forests, mountains, villages, and the sound and chill of rivers—so that when he is later confronted with a landscape painting, it will trigger a chain of associations invoking all of his senses.68 In the virtual reality thus engendered, both the artist and the beholder meet each other, as it were:

for as the Artificers that doe goe about their workes filled with an imagination of the presence of things, leave in their workes a certaine spirit drawne and derived out of the contemplation of things present; so is it not possible but that same spirit transfused into their workes, should likewise prevaile with the spectatours, working in them the same impression of the presence of things that was in the Artificers themselves.69

Synaesthesia

We have seen that Junius’s ideal of artistic contemplation consists in empathizing with the characters in a story and evoking the narrative in the mind’s eye, “not otherwise then if wee were present, and saw not the counterfeited image but the reall performance of the thing.” In his theory, painting, just like rhetoric, is a performative art, one in which speaking is doing. Representing the scene is acting it out—an activity ultimately involving one’s own body and sensory faculties.

Several senses of the term performative apply here. In an abstract sense, according to Junius’s theory, “painting” is “doing.” Making art is bringing figures to life and experiencing emotion itself, just as looking at art equals immersion in another reality. Junius speaks of how the artistic experience leaves us with the impression “as if we were doing rather than thinking.”70 The English edition explains how images of foreign countries bring about the experience of real travel, images of battles provoke real anguish, and images of political scenes inspire our own speeches:

wee shall with much ease attaine to [conjure up mental images] . . . if wee are but willing: for as among the manifold remissions of our minde among our idle hopes and wakefull dreames, these Images do follow us so close, that wee seeme to travell, to saile, to bestirre our selves mightily in a hot fight, to make a speech in the middest of great assemblies, yea wee doe so lively propound all these things unto our minds, as if the doing of them kept us so busie, and not the thinking [italics mine, TW].71

The Painting of the Ancients uses the term “performance” in a manner close to the modern meaning of “performative”: just as words become deeds in a speech act (to use the technical term related to performativity), in Junius’s theory, images become actions. Most obviously, however, painting is performative in the sense that the beholder becomes involved in the depicted story as a spectator or even as an agent in the narrative. Since looking at a painting is ideally the mental re-creation of an event as if it were staged or play-acted, the beholder “makes himself present” and becomes part of the work of art. Hence it is the visual arts that allow ancient masters and modern beholders to share the same virtual reality. Ideally, appreciating art is a synesthetic experience in which movement, sound, and even smell are conveyed. This is essentially Philostratean theory. To quote Philostatus the Elder on a scene of cupids frolicking in a garden, which with its colors, scents, and movements invites the spectator himself to take a walk and lie down “in” the painting (from Images1.6):

Do you smell the fragrance that spreads through the garden, or haven’t your senses responded yet? But listen carefully, for along with my description of the garden the fragrance of the apples will come to you. Our senses fully alerted, we then follow the description through the orchard: Here the trees grow straight, and there is space between them to walk in, and tender grass covers the paths, fit to be a couch to lie upon.

In effect, this quotation is part of Philostratus’s description of “Amori” or cupids (see fig. 4), which was the basis for Titian’s painting The Worship of Venus (see fig. 5). When Rubens, in turn, imitated Titian’s work, it may have been a conscious exercise in that kind of evocative art that appeals to the eye only to make an impact on the mind—and virtually engages all the senses (see fig. 6-8). As David Rosand noted, whereas Titian’s experiment with ekphrasis involved turning the poets’ words into paint, Rubens did not content himself with simply copying this facture and palette but rather took up the challenge to get inside Titian’s original mental image, complete with its movements, sounds, and scents. Stylistic and technical comparison confirms this contention; for Rosand, “there is hardly a motif in Titian’s Andrians that is not modified in some degree by Rubens.”72 Jeremy Wood has studied in greater detail how Titian’s originals’ “dense and opaque surfaces . . . are quite unlike the transparency of pigment found in . . . Rubens,” who introduced a bluish element to the flesh tones that made the copies look paler and more “silkish” than the Titians.73 This manifest lack of concern with his great predecessor’s brushwork may have been related to the classical theory reconstructed by Junius. The proper reaction to a great work of art was apparently not a consideration of lines and colors but an exploration of its “mysteries”—which, in Junius’s theory, means a profound mental evocation of people, movements, sounds, scents. Only the ignorant, when imitating someone else’s works, “fall to worke upon the first sight, before ever they have sounded the deep and hidden mysteries of Art, pleasing themselves wonderfully with the good successe of their Imitation, when they seeme onely for the outward lines and colours to come somewhat neere their paterne.”74 Rubens was reputed to take such statements seriously; van Hoogstraten notes that in contrast to his contemporaries, when the master was confronted with the masterpieces of Rome, he refrained from making drawings of them and tried to capture their essence in his mind.75

Via Junius, van Hoogstraten also knew Philostratean synaesthetic theory. He quotes, for instance, from a passage describing such a lifelike representation of horses that one sees their nostrils flaring, hears their whinnying, and senses their excitement: “They whinny fast, nostrils raised, or do you not hear the painting?” The painter repeats Philostratus’s astonishment “that art brings forth so much that from the flared nostrils [of these horses], from their pressed-down ears and taut limbs, one perceives their keen desire to flee, even though one knows that they are motionless.”76 To explain how the artistic experience may engage other senses than sight alone, Junius repeats a well-known ancient anecdote about the artist Theon, who had a trumpet sounded at the unveiling of his painting of a soldier: “The most excellent Artificer conceived very well that the phantasie of the beholders would fasten soonest upon such a representation, if it were first mooved by this dreadfull noise.”77 Once again, the Dutch edition is more elaborate when it comes to the “living presence of the represented thing” (de levendighe teghenwordigheyt van d’afghebeelde saecke). The passage illustrates how image and sound could ideally be combined to evoke an even more persuasive virtual reality. The common practice in the seventeenth century of putting paintings behind curtains made real this ideal of art as a scene “acted out before [one’s] eyes.” Van Hoogstraten took Junius’s theory to heart when he stressed the affinities between stage and studio; he went so far as to train his pupils in play-acting, the scripts for which he wrote himself.78

Painted Pain

Although van Hoogstraten may have taken this ideal of mental staging more literally than Junius himself intended it, such linking of painted stories to the actual stage was actually close to the intent of Junius’s ancient sources. There was a certain continuity whereby the original import of the latter was still understood in the early modern age as being essentially linked to a practice of “reall performance.” That scenes of history and mythology should be conjured up in such a manner that viewers thought they were present at the scene, reflected the public performance of “mythological exhibitions.” Martial’s Book of Spectacles (first century AD), to give one example, describes scenes that took place in the Flavian amphitheater (the Colosseum). Live enactments of mythological events took place here, such as Pasiphae copulating with a bull or Prometheus being eviscerated: the execution of criminals was thus staged as a grisly performance.79 The ancients’ theory of emotional arousal through confrontation with real performance seems to have been inspired by what was concrete staging practice. Echoes of this time-honored tradition resonate in Junius’s book, for instance when he recalls an anecdote from Seneca the Elder’s Controversies (10.5): after painting Prometheus’s punishment by the gods, the artist Parrhasius was accused of torturing a slave to serve as his model.80

Parrhasius, of course, had been faithful, to the letter, to the notion that the artist should make himself present at the very event he wants to evoke for the affective arousal of the public. Rubens, in focusing his Bound Prometheus (1611–12) on the precise moment when the eagle tears out Prometheus’s liver, may have taken Seneca’s statement to heart—after all, this was one of the authors he reportedly had read to him while he painted (fig. 16).81 He probably also knew an ekphrasis of the Prometheus theme by Achilles Tatius, who said that “you cannot help feeling pity even for what you know is only a picture.”82 For Junius, who may have come across this painting after Sir Dudley Carleton acquired it in 1618,83 the idea would clearly be that the beholder is ultimately physically repulsed by such an image. According to his response theory, the artist, the depicted figures, and the beholder share the same affective involvement. In relation to the viewer, there seems to have been a forerunner to his idea in Antwerp humanism: Carolus Scribanius wrote about a painted Saint Sebastian that “those who look at the martyr’s wounds, are wounded themselves” (fig. 17).84

An even more striking example is to be found in Rembrandt’s studio. Perhaps after Rembrandt discussed this matter with Huygens, his works of 1635–36 show a remarkable adherence to the ideal of the engagement of the viewer, as discussed above. To Junius (quoting Longinus) painterly narrative is, first of all, effective when avoiding “fabulous excellencie” and striving after “possibilitie and truth”: Rembrandt embraced a similar ideal with his Danaë (1636, St. Petersburg), which famously involves Cupid only as a sculpted figure in the woodwork decoration; likewise his Rape of Ganymede (1635, Dresden) features not a stylish young man but a toddler recognizable to any Dutch parent, crying and urinating from fright as he is lifted by an eagle. In a further exploration of physically engaging art, Rembrandt seems to have been trying to virtually hurt the viewer. In 1636 he painted his Blinding of Samson, probably an emulation of Rubens’s Prometheus.85 He foregrounded a scene of torture, making it all the more discomforting for his public because it is the eyes that are being put out—in a grating visual counterpoint with Delilah’s unflinching gaze directed at the viewer (fig. 18).

Such blurring of the line between fiction and an individual’s felt reality is also evident in Junius’s high regard for the ancient actor Polus, who was not content with showing feigned sorrow on the stage. When he had to play Electra carrying her son’s urn he went so far as to have the grave of his own child opened up: “having digged up the bones . . . and bringing them upon the stage . . . hee found himselfe forced to play the mourner after a most complete and lively manner.” Hence, he filled the theater “not with an affectation of weeping and wailing, but with true and naturall teares.”86 In this, Junius’s stance is corroborated by modern aesthetics: in contrast to the fiction of art, emotions are real experience, and therefore constitute the strongest form of persuasion. It is here that the full import of Quintilian’s statement that orators who want to move their audience should first experience the emotion themselves becomes clear:

A minde rightly affected and passionated is the onely fountaine whereout there doe issue forth such violent streames of passions, that the spectator, not being able to resist, is carried away against his will . . . “Afflicted folks, their griefe beeing as yet fresh,” sayth Quintilian, “seem to cry out some things most eloquently . . . If therefore we do desire to come neer the truth, it is requisite that we should finde our selves even so affected as they are who suffer indeed [italics mine, TW].”87

We now understand better Junius’s statement that the viewer’s confrontation with art’s physical reality may strike fear into him,88 or a remark by Gerardus Vossius, the Dutch Republic’s foremost rhetorician, that the works of Protogenes were so lifelike they could not be seen without inspiring terror (quodam horrore).89 Samuel van Hoogstraten, who may have encountered Junius’s book in Rembrandt’s studio, follows the lead of these luminaries of classical learning when he describes paintings the sight of which made viewers turn pale, and others that people did not dare to touch.90 Writing for an audience of young artists, he quotes Longinus on the “truly great” (waarlijk groots), as “that which appears before our eyes each time anew as if fresh; which is difficult, or rather impossible, to banish from our thoughts; the memory of which seems to be constantly, and as if indelibly, engraved on our hearts.”91 Here it seems to be the Junian reaction to art, leaving the viewer in extremis in physical pain, that is being understood.