Two recently discovered ivory objects carved in Sri Lanka – a pipe case and a sculpture of the Virgin and Child, testify to the sophistication of Sinhalese artistic responses to European trading networks in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This essay seeks to contextualize these objects and to highlight the connections between the Portuguese and Dutch empires, normally conceived as separate entities in perennial conflict. Even as scholars turn increasingly to the relationships between the Netherlands and Asia, the limitations of national categories as a means of understanding world trade become evident.

Two recently discovered ivory objects carved in Sri Lanka, the finest of their respective types, testify to the sophistication of Sinhalese artistic responses to European trading networks. Even as scholars turn increasingly to the relationships between the Netherlands and Asia, the limitations of national categories as a means of understanding world trade become evident. This essay will consider the multiple contexts of these objects, now in the collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum, and related works, especially as they highlight the connections between the Portuguese and Dutch empires, normally conceived of as separate entities in perennial conflict.

Trevor Barton (1920–2008), a noted collector of smoking paraphernalia, acquired from an unknown source an unusual ivory pipe case made in Sri Lanka in the seventeenth century (fig. 1).1 A few similar works are known, but this example, now in the collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore, is the most elaborate and most intricately worked. The long, tapering box has a small door that unlatches to reveal two tubes that would have held long thin tobacco pipes. Common in the Netherlands, such clay pipes were a special product of Gouda,2 and they can be seen lying on tables or littering the ground in innumerable Netherlandish still lifes and genre scenes. As the Dutch developed an overseas network in the seventeenth century, the pipes circulated around the world at the trading posts of the Dutch East India Company.

This pipe case is a highly refined, Asian version of a utilitarian European object that would have usually been made of wood or leather.3 Its ivory panels have been carved with openwork vines and small flowers; children and winged cherubs cavort in the tendrils (fig. 2). The pierced panels are backed with sheets of mica to reflect light and enhance the delicacy of the decoration. The object combines artistic impulses from both East and West. The form of the case and the angels are Western, while the pattern of vines is typical of South Asian design. The grimacing lion that forms the handle on the lid (fig. 3) can be recognized in Dutch as well as South Asian iconography. However, the lotus bud, which forms the finial at the narrow end of the case, is a prominent Buddhist symbol.

This is the most elaborate and finely worked example of the few known Sri Lankan ivory pipe cases. A pipe case in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (fig. 4), is simply carved and was evidently more cheaply and quickly produced.4 The design is rendered in shallow relief, while the patterns on the sides change rather abruptly between panels. The pipe case in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (fig. 5), is carved with openwork, like the example in Singapore, but the scrolling vines contain no figures, and the object lacks an ivory finial and knob.5 Two other pierced cases (Spink, London, 1998; and private collection) are also backed with mica and have floral pendants, but have no putti.6 Closest in style to the pipe case in Singapore and sharing most of its features is a work, which may have originated in the same workshop, preserved in the Nationaal Farmaceutisch Museum (the former De Moriaan Museum), Gouda.7 These Sri Lankan ivory pipe cases must have been made for Dutch buyers since the cases were meant to store long pipes of the style favored by the Dutch but not used by the Portuguese, the other European trading power in Asia during the seventeenth century. Moreover, the imagery of the carving is distinct from the highly figural designs created for Portuguese patrons and collectors. The putti found in the pipe case (see fig. 2) may represent a transitional stage between the two European cultures, as suggested below.

Ivory Carving in Sri Lanka before the Arrival of the Dutch

Sri Lanka had been celebrated for the sophistication of its ivory carving centuries before the Dutch arrived in the mid-1600s. The island was and is predominantly Buddhist, and over the centuries it produced a range of exquisite carvings of Buddhist subjects and themes drawn from epic Indian narratives. Ivory combs were carved with various deities, especially yakshnis, voluptuous female attendant deities present in both Hinduism and Buddhism, as seen in an elaborate openwork example with three yakshnis arranged in a network of vines (fig. 6).8 Sri Lankan artists adapted their styles to different patrons, both local and foreign, and seem to have shifted seamlessly from local Buddhist subjects to the Portuguese taste for Christian images, and later to Dutch demands.

Portugal made contact with Sri Lanka in 1505 and established permanent trading ports there in 1517, first at Kotte and then at Colombo. The Portuguese began to purchase fine objects fashioned from rare and precious materials, such as rock crystal and ivory. The Portuguese commissioned Christian figures carved in ivory, which in the sixteenth century were not mere copies of established European types but innovative amalgams of style and form. The largest and finest known ivory Christian sculpture made in Sri Lanka recently entered the collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum (fig. 7). Measuring thirty-two centimeters high, the figure is carved with great detail and sensitivity from a single piece of African ivory. Many features of the iconography are familiar from Renaissance imagery in the West: the Virgin stands on a crescent moon and holds the Christ Child, who carries an orb. She may have once carried a rosary fashioned in gold or gemstones.9

On the other hand, the treatment of the face shows strong Sri Lankan characteristics. The Virgin also wears jewelry that is South Asian in character. As Pedro Moura Carvalho observes, a remarkable Buddhist element was added to this Christian image: trivali on the necks of the Virgin and Christ.10 These three rings distinguish representations of the Buddha, and their presence on the Virgin and the Christ Child shows that the Sri Lankan carver added elements considered essential to a deity, regardless of religion.

Perhaps the most local aspect of the sculpture is the delicate treatment of the drapery, which falls in precise, even pleats and is bordered by intricate ruffles along the edges. The overlapping garments are rendered with elegance and believability, contributing to the grace of the figure. Such artistic techniques had been perfected in earlier Sri Lankan sculptures of the Buddha and bodhisattvas.

Ivory Objects for European Courts

The political connections between Portugal and Sri Lanka were strengthened in the 1540s when the Sinhalese ruler Bhuvaneka Bahu (r. 1521–51) sought the support of the Portuguese king Dom João III (r. 1527–57) to overcome local rivals. A mission was sent to Lisbon in 1542, resulting in the symbolic coronation of Dharmapala, Bhuvaneka Bahu’s grandson, by the Portuguese king. At this time, sumptuous gifts were presented to the Portuguese court, including jeweled objects and intricate folding fans made of ivory.11

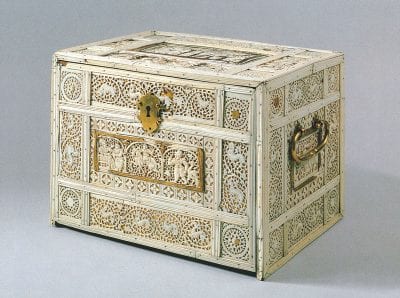

The most prestigious ivories presented to the Portuguese were a series of caskets produced in the middle of the sixteenth century, mostly decorated with gemstones and gilded metal mounts.12 The panels depict a variety of scenes drawn from epic poetry as well as contemporary events, including the coronation of the Sri Lanka monarch by João III, as seen in the casket preserved in the Munich Schatzkammer.13 King Bhuvaneka Bahu presented four ivory caskets to the Portuguese monarch, and these gifts triggered a demand in a wider aristocratic circle.14 Only approximately a dozen of the ivory caskets are known; three have been in aristocratic collections since the sixteenth century, namely those of Albrecht V, duke of Bavaria (1528–1579) and Ferdinand II, archduke of Tyrol (1529–1595).

The pierced and intricately carved panels which make up the pipe case can be directly compared to the finest cabinets and caskets made for the Portuguese a few generations earlier. One example is the writing cabinet in Vienna, which entered the Habsburg collections in the seventeenth century (fig. 8).15 Delicate openwork ivory panels are backed with mica, the identical technique employed on the pipe case.

The Dutch in Sri Lanka

In 1656, the Dutch captured the Portuguese fort at Colombo and thereafter dominated trade in and out of the island until they were replaced by the British in 1798 as a result of the Napoleonic conflicts. In addition to trading in spices and other commodities, the Dutch also commissioned furniture and some luxury items from Sri Lanka to be taken back to the Netherlands or to the major Dutch outposts in Asia, Malacca and Batavia (Jakarta).

We need to consider the circumstances of the making of the pipe case now in Singapore, since its quality is considerably greater than that of other examples. Indeed, its technique and refinement can be compared with the earlier ivory works acquired by the Portuguese. The first pierced ivory cabinets to come to Europe were gifts from the Sri Lankan ruler, rather than commissions, and it is possible that the ivory pipe case was also a gift to a Dutch official after the Dutch took possession of the Portuguese holdings on the island. The gift of an ivory casket to the Portuguese viceroy of Sri Lanka, Dom João de Castro, in 1547 is an important precedent. Now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (Kunstkammer 4743), that work is finely carved but not as elaborate as the caskets presented directly to the Portuguese court.16 Pierced and finely carved ivory was not only a prized art form in Sri Lanka, it had also been highly valued by the Portuguese in the century before the Dutch took possession of the island. What better diplomatic gift than a highly refined version of a typical Dutch object?

Clay pipes were sometimes kept in special cases to prevent breakage, but the ivory case is as delicate as the pipes themselves and was probably of purely ceremonial use. The double container suggests that the object was meant for use in welcoming an honored guest. Cherubs and putti can be found in only two ivory pipe cases. Together with the elaborateness of the openwork and the mica backing, this suggests that the production of the object retained some influence from the Portuguese period. This makes it likely that the pipe case now in the Asian Civilisations Museum was a diplomatic gift for a Dutch official soon after the Dutch ascendance in Sri Lanka. And its unique opulence within the group suggests that it is the earliest of the Dutch pipe cases.

Dutch trade elsewhere in Asia led to the creation of a comparable object in another highly prized material. A Japanese lacquer case, delicately decorated with a few leaves rendered in gold, was also meant to contain two long clay pipes (fig. 9). It dates from the first decades of the eighteenth century, a significant period because after 1641 the Dutch Republic was the only Western nation allowed to trade with Japan. Limited to the island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor, the Dutch were allowed to export Japanese goods on a handful of ships each year, making the lacquer pipe case a luxury item of considerable rarity.17 Cases for long Dutch clay pipes were also made of wood in Asia. An ebony case apparently dating from the seventeenth century or early eighteenth century was made on the Coromandel Coast of southeastern India or perhaps Sri Lanka (fig. 10).

Sri Lankan rarities were eagerly collected by the Portuguese court and were presented to Habsburg relatives. In contrast, the Dutch East India Company had no aristocratic patrons and scant connections with the stadhouder, which means that Sri Lankan luxuries are not recorded in the Orange inventories in the seventeenth century. However, a few Sri Lankan ivories appear in other Protestant aristocratic collections. For example, an ivory casket and a circular box are recorded in 1668 in the Kunstkammer of Frederik Wilhelm, elector of Brandenburg, and by 1690 the Copenhagen Kunstkammer had a comb and a dagger.18 The Berlin objects may have a Dutch source since Frederik Wilhelm was married to Louise Henriëtte, daughter of Stadhouder Frederik Hendrik. In 1754, the Dutch governor of Batavia, Julius Stein van Gollenesse, who had been governor of Sri Lanka between 1742 and 1752, sent a selection of Indian jewelry to the court in The Hague.19

Adam and Eve

In addition to the pipe cases, another group of Sri Lankan ivories has been connected to Dutch seventeenth-century patronage. Several cabinets or parts of cabinets survive that depict Adam and Eve (fig. 11).20 Many of the representations are closely connected, with the gestures of the figures being very similar, which points to the use of a single source. Jan Veenendaal considered this to be a print by Matthäus Merian (1593–1650) that also included an elephant.21 However, Adam and Eve in a forest landscape, surrounded by a variety of animals, can be found in numerous Netherlandish images, including several paintings by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), Roelandt Savery (1576–1639), and others, as well as in a print by Rembrandt of 1638. Elephants and other exotic animals commonly appear in Dutch representations of the Garden of Eden or of Orpheus.22 There has been a tendency to identify prints as the primary means of transferring Western imagery to Asia, whereas in practice, there may have been many drawings and decorative objects that depicted the subjects, although they may not have survived.

Adam and Eve were certainly far more commonly encountered in Dutch art than were New Testament scenes, although this alone cannot explain the popularity of the Sri Lankan ivory cabinets. There may be a more popular association: in Sri Lanka there is a mountain traditionally thought to be the site of Buddha’s footprint, but also called “Adam’s Peak.” Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, the Dutch secretary of the archbishop of Goa, recorded in 1597 that Adam’s Peak was thought to be the place where Adam had been created.23 Rather than meant to depict specifically Protestant iconography, the ivory cabinets may have been souvenirs of a famous site on Sri Lanka.

Ebony Furniture

The complex foliage, frolicking animals, and cherub heads found in the pipe case can also be seen in the ebony furniture produced in the late seventeenth century on both Sri Lanka and the Coromandel Coast (fig. 12). This furniture was produced in much greater quantities than were the ivories, and while ebony is a valued material of great density and luster, it does not approach ivory in rarity.24

The dense black ebony wood used to make the side chair has been pierced and carved in intricate designs, which gives it a sense of lightness and delicacy. The chair mixes European and Indian motifs. At the center of the crest rail is a winged head. A profusion of scrolling vines emerges from a vase below. On either side are women and fantastic scaled beasts. Birds perch on the stiles. A winged head and makaras (mythical sea creatures) appear on the lower rail, and two other fantastic creatures are carved into the chair rail. Spiral turning, familiar from seventeenth-century European furniture, is used for the legs, cross pieces, and balusters.

Ebony furniture appears to have been produced for the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British. Several pieces are recorded in Batavian inventories in the 1640s, including two chairs carved from ebony from an island in the Moluccas, in 1644.25 Amin Jaffer has traced a large number of South Asian ebony pieces to British collections of the eighteenth century, when they were sometimes thought to be early English furniture.26 The Coromandel Coast, the major center for the production of ebony furniture, traded actively with all three European powers. It is therefore difficult to distinguish the designs of ebony furniture preferred by the Dutch from those of the British, given the objects’ limited provenance. Large floral motifs, including tulips, appear on some examples, like the large four-poster bed in the Rijksmuseum, but the place of manufacture of this eighteenth-century work cannot be pinpointed securely.27 The situation is made more difficult because the English demand for ebony furniture in the early nineteenth century led to the import of earlier pieces from Holland and Sri Lanka.28

The Portuguese may have been the first to commission ebony furniture of this type. On her marriage to Charles II in 1662, Catherine of Braganza brought to London luxury goods made in India for the Portuguese. Her dowry also included Portuguese territorial possessions such as Bombay and Tangiers, which passed to the British crown. Her possessions appear to have included two ebony chairs now in the Ashmolean Museum, which were reportedly presented by Charles II to Elias Ashmole, who in turn gave them to the Ashmolean Museum in 1683.29 Despite the doubt about the Indo-Portuguese origins for this type of chair expressed by Amin Jaffer, the connection with Catherine of Braganza is plausible.30 The wide distribution of South Asian ebony furniture in Britain and the Netherlands testifies to the complex trade patterns of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, since materials and designs were used in different regions by the colonial networks. It is possible that ebony furniture with scrolling foliage, mythical creatures, and winged cherubs was carved in several different centers — Sri Lanka, the Coromandel Coast, and Batavia — by artisans of different ethnicities. Joan Nieuhoff around 1670 reported that Batavia had workshops of ebony furniture makers that employed craftsmen from Java, Holland, and China, as well as slaves from Sri Lanka and the Coromandel Coast.31

A picture of the household possessions of residents in overseas Dutch territories is slowly emerging as records connected with Cape Town, Jakarta, and Malacca are transcribed and analyzed.32 While these do not document ivory pipe cases, they show an active international trade in goods across the Indian Ocean. A wealthy Dutch resident in Malacca, Jakarta, or the Cape typically owned objects from India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Manila, Java, China, and Japan. Officers and merchants moved between Java and the Cape, with the result that objects, clothing, and even paintings traveled between the two continents. This network suggests that it is a mistake to divide the Dutch overseas experience into spheres of the Cape, Sri Lanka, Malacca, Java, and so forth. Moreover, it may be unwise to consider the Dutch overseas as a contained entity.

The linguistically and politically determined avenues of research that have demarcated European art history into national schools have now infiltrated non-Western art histories. Museums and scholars have tended to treat the Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, and British in Asia as direct extensions of national cultures in Europe.33 The result has been to emphasize the differences between the Asian goods produced for these nations, rather than their similarities and interconnectivities. Sri Lanka is a good example of this, with supposedly Catholic objects linked to Portuguese taste and nonfigural objects associated with the Dutch.

British observers sometimes express surprise that the Dutch had been so active in India and Asia before the British moved in. One might suppose that the Dutch might be even more surprised by the vast trading empire of the Portuguese, which started much earlier and developed much more extensively than its successors. All too often, discussions of the Western powers in Asia dissolve into polemics about which imperialists behaved better or worse. In fact, the overlapping trade patterns of the Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, and British are more similar than different — especially from the Asian perspective. And looking beyond the European colonial powers, comparable roles were played by China and India, which had their own systems of trade and tribute.

The restrictions of such nationalist approaches have been noticed by the historian David Ludden: “Many scholars have become implicitly committed, like nationalists, to boundaries between insiders and outsiders built by race, language, nation, culture, and civilisation.”34 Ludden has observed that rather than dividing Asia from Europe, and maintaining the separate European colonial systems, the extensive trading networks in the late Renaissance meant that, “Europe, India, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia formed a single, modern cultural region.”35 The Mediterranean world posited by Fernand Braudel may be considered to have had a close parallel in the trade systems centered on the Indian Ocean.

The Portuguese and Dutch trading empires were closely linked on many levels, even through periods of armed conflict and intense political rivalry. Commerce and artistic exchange continued through the seventeenth century even as the two powers struggled for control of Sri Lanka and Malacca and of trade with Japan. One reminder that the Dutch and Portuguese were interwoven throughout Asia can be found as early as 1597 with the publication of Itinerario: Voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huyghen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien by the Dutch chronicler and illustrator of Portuguese Asia Jan Huyghen van Linschoten. Despite their expanding presence in Asia, the Dutch could never replace the entrenched and sophisticated Portuguese network of trade in luxury goods. This can be glimpsed even in the paintings of Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675). In two of these, a woman in a fur-trimmed garment turns from her desk on which rests an elegant casket, inlaid with various woods and decorated with silver mounts (fig. 13, fig. 14). This casket is clearly the work of Indian artisans, made for Portuguese traders and shipped to Europe from Goa.36 Even as the Dutch turned east in the seventeenth century, they continued to depend on other European trading networks for their procurement of foreign goods.