In 1625 Isabel Clara Eugenia commissioned from Peter Paul Rubens a stunning twenty-tapestry cycle known as The Triumph of the Eucharist for the Royal Convent of the Discalced Clares in Madrid. In this cycle, Rubens designed eleven of the twenty tapestries to feature their narrative scenes in trompe l’oeil. It has long been argued that in doing so, Rubens sought to evoke the eleven curtains of the tabernacle in the temple of Solomon. This study reexamines the Solomonic theme through the political context of the series’ patron, Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, archduchess of Austria and governess general of the Spanish Netherlands. It posits that by calling on the Solomonic imagery, Isabel wished to liken herself to the fair and wise Old Testament leader, thereby metaphorically announcing her suitability to govern the Netherlands with a freer hand than she had been allowed up to that time.

In 1628, Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia (1566–1633), archduchess of Austria and governess general of the Spanish Netherlands, sent the first shipment of tapestries of Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist series to the Royal Convent of the Discalced Clares in Madrid.1 She had commissioned the cycle three years prior, and, appropriately for a convent that was home to the Franciscan Order of the Poor Clares, a group particularly devoted to the Eucharist, its compositions featured Old Testament prefigurations of the Eucharist, prophets and protectors of the Eucharist, wagons and victories marking the power of the Eucharist, as well as images of angels and lay and clerical figures in adoration of the Eucharist. Rubens (1577–1640) composed each of the twenty scenes to feature larger than life-size figures, seventeen of which are set in shallow architectural frames, to make these images of Eucharistic triumph forcefully evident to the viewers. He used vivid colors to enhance the visual impact of the textiles, and he designed the cycle to hang edge-to-edge in two tiers throughout the church (fig. 1).2

Perhaps most notably, for eleven of these twenty textiles, Rubens pictured the narrative scenes as if they were themselves hanging on tapestries from architectural surrounds (fig. 2). In so doing, he created trompe l’oeil tapestries within the tapestries. For decades scholars have argued that this conceptual conceit served the religious aim of reconfiguring the interior of the church to evoke the temple of Solomon. According to the book of Exodus, God called upon the Jews to make eleven curtains of goat hair to cover the tabernacle, which contained the Holy of Holies–the dwelling place of God in the temple.3 In the center of the tabernacle stood a chest, the Ark of the Covenant, which had accompanied the Israelites on their wanderings in the desert and their journey to Jerusalem, where the tabernacle was ultimately housed within the temple of Solomon.

Visitors who entered the Royal Convent of the Discalced Clares, or the Descalzas Reales as it is commonly called, would have felt transported to another realm–a realm that recalled the long lost tabernacle. “In physically covering the walls of the chapel,” Charles Scribner wrote, “Rubens’s tapestries conceptually and illusionistically recovered the ancient, long since destroyed Holy of Holies, here transformed into its new Christian identity wherein the Ark is replaced by God’s Eucharistic presence” [emphasis in original].4 Each nearly five meters tall, The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestries would, indeed, have visually and physically transformed the convent church with their iconographically complex, symbolically rich, and aesthetically stunning imagery. This imagery celebrated one of the most fundamental ideals of the Counter-Reformation: the eternal victory of the Holy Sacrament.

Isabel’s decision to present The Triumph of the Eucharist series to the Descalzas Reales was a logical choice. Religious life at the convent culminated in elaborate celebrations of the Eucharist on Good Friday, when the death of Christ is commemorated within the Easter liturgy, and during the Octave of Corpus Christi, the vernal celebration of Christ’s real presence in the Eucharist. Yet, given the intimate connection between religion and politics in Habsburg countries, where piety (and pious organizations) often affirmed political power, the donation to the Descalzas Reales was also tactical. The Descalzas Reales was the nucleus of religious life for all Spanish Habsburgs in Madrid, including the male members of the family, and, specifically, the king, who worshiped there during the Eucharistic festivities, when The Triumph of the Eucharist series was displayed. To that end, Rubens’s concetto may be read as a projection of both the sacred and secular aims of the infanta. At the time that she commissioned the tapestry cycle her sixteen year-old nephew, and the new king of Spain, Philip IV (1605–1665) had recently demoted her from sovereign regent of the Spanish Netherlands to the post of governor. The demotion meant that she had lost control over her war budget, the court’s political infrastructure, and decisions regarding domestic or foreign policy. By calling on the imagery of Solomon, The Triumph of the Eucharist series aligned the infanta with a venerable past and metaphorically announced her suitability to govern the Spanish Netherlands with a freer hand than her nephew had so far allowed.

Solomonism in the Habsburg Tradition

According to the book of Chronicles, the reign of Solomon was a golden age in the history of Israel. The biblical text describes how Solomon was elected by God to be king and saw to completion the building of the temple that established a permanent residence for the tabernacle and the Ark of the Covenant–the chest containing the original tablets of the Ten Commandments. Prior to Solomon, the tribes of Israel were nomadic and worshipped God in disparate ways. However, when Solomon built the permanent temple to house the tabernacle and the Ark of the Covenant, he united the different tribes and reigned over a period of peace.5

Owing to Solomon’s pious and political reputation,Habsburg monarchs routinely likened themselves and their endeavors to the Old Testament king. This was especially true for King Philip II of Spain (1527–1598), Infanta Isabel’s father.6 Solomon was a model of wisdom and prudence, an exemplar of good judgment and morality, and his temple represented the height of state and religious authority. To exploit a connection to these values, Habsburgs emulated Solomon in their quest for a New Jerusalem. In his 1559 commission of a painting depicting Queen Sheba’s visit (fig. 3) for St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Philip II had himself pictured as Solomon in the image. References to Philip II as a new Solomon emerged as early as his tenure as crown prince. As Rosemarie Mulcahy has noted, this was because “both [Solomon and Philip] carried out an idea initiated by their fathers (King David and Emperor Charles V), expanded on their territories that they inherited and consolidated, and spread the one faith.”7 During Philip’s “Fortunate Journey” in Northern Europe during 1548–51, the cities of Haarlem, Ghent, Bruges, Lille, Tournai, The Hague, and Leiden all welcomed him with the slogan “Solomon is anointed as king, in the lifetime of his father.”8

Comparisons of Philip II to Solomon may also be found in a variety of writings throughout Philip’s kingship. The Spanish Baroque poet Luis de Góngora hailed him as a “Salomón segundo” in Sacros, Altos, Dorados Capiteles (1585),9 and Juan Rafael de la Cuadra Blanco has noted how Fray Julián’s de Tricio in a letter to Philip in 1575 wishes the king a long and prosperous life so that, like Solomon, he might surpass all the great monarchs that came before him and that would succeed him.10

Philip II’s most important example of Solomonism is surely the royal monastery-palace complex, San Lorenzo de El Escorial. José de Sigüenza, a chronicler of El Escorial, who published an account of the building’s founding in 1605, hailed the complex as a successor to the ark of Noah, the tabernacle of Moses, and the temple of Solomon.11 In her analysis of the royal basilica of El Escorial, Mulcahy observes that when Philip II began construction on the site, he certainly envisioned it to represent the Solomonic temple anew.12 Statues of King David and Solomon flank the entrance of the basilica, and Solomon is represented in a large-scale fresco by Pellegrino Tibaldi in El Escorial’s library. Just behind the altar in the royal basilica, Philip II constructed a tall, very narrow room called the Sagrario that accesses the back of the tabernacle, which he likened to the inner sanctum in the temple of Solomon. Like the Ark of the Covenant in the Holy of Holies in the temple of Solomon, the Holy Sacrament in the Sagrario was perpetually exposed, and, in imitation of the eleven curtains of the tabernacle, its walls were frescoed with trompe l’oeil hangings (there was room for only four) (fig. 4). Philip II even had the vault painted with cherubim that were thematically akin to the angelic consorts embroidered according to the book of Chronicles on the innermost covering of tabernacle–a Solomonic component that Rubens also included in several of The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestries, when he used putti to help suspend the tapestries from the architecture he depicted (fig. 2, fig. 5-7). Further, in imitation of the inner sanctum of the temple of Solomon, where access to the Holy of Holies was limited to the high priest and to Solomon, only Philip II and the priest had access to the Sagrario and the Sacrament within. According to the book of Kings, Solomon “used to offer up burnt offerings and peace offerings upon the altar on the dedication of the temple, and perennially on the holiest of feast days” (I Kings 9:25)–a scene Rubens portrays in The Sacrifice of the Old Covenant (fig. 8).

Although construction on El Escorial began before Infanta Isabel was born, it continued well into her adulthood and was ongoing when she left Spain in 1599 to assume sovereignty over the Netherlands. She was exceptionally close to her father and was his favorite child and protégé, outshining even his son, the future King Philip III (1578–1621).13 Philip II went to great lengths to train his daughter in the theories and acts of kingship, including bringing her to artists’ workshops to teach her important lessons about managing commissions and generating the royal image. At El Escorial, she joined her father on visits to workshops with him to check on the progress of the building’s decorative program and even developed friendships with many of the painters.14 Isabel was so intimately knowledgeable about the artistic goings-on at the construction site that when in 1606 Pompeo Leoni’s gilt-bronze effigies of the families of Charles V and Philip II were finally ready to be installed, eight years after the king’s death, Isabel was consulted about where her father had wished the sculptures to be placed, even though she had not lived in Spain for seven years.15

This history leaves no doubt that Isabel Clara Eugenia was fully aware of the importance of a Solomonic association in the establishment of royal identity. She had observed her father following Solomon’s example and putting his energy and resources into constructing the Catholic successor to Solomon’s Temple of the Most High in Jerusalem. She knew that by doing so Philip II made El Escorial a symbol of political and religious unity, thereby visually publicizing the sacral nature of his royal power.

Isabel Clara Eugenia’s Problem of Authority

At the time that Isabel commissioned The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series from Rubens, she desired nothing more than to restore political and religious unity in the Netherlands under her leadership, as it had been under her grandfather and father. For nearly sixty years, seven of the northern provinces had been actively rebelling against the Spanish crown, in whose name the infanta governed. Yet any peace talks or movements toward reconciliation relied ultimately on the Spanish king, Philip IV.16 As the infanta once lamented, “Although everything passes through my hands, final resolution lies in Spain.”17

Isabel had not always been so politically impotent, for she had previously acted as sovereign. The Netherlands was the wedding gift of her father to her and her husband, Archduke Albert of Austria (1559–1621). However, the transfer was burdened with stipulations. In the eleven clauses that composed the Act of Cession, which outlined the transfer of the Netherlands to Infanta Isabel, it was enjoined that the domains be inherited according to the rules of primogeniture and that if Albert and Isabel produced only a daughter, she would either marry the king of Spain or someone of his consent.18 Other articles specified that only Catholic princes could inherit the land; that the archduke and duchess must pledge their fidelity to the Catholic Church and condemn as heretics any member of their family who refused; and that the ceded territories return to the Spanish crown in the event that they remained childless. When Albert died in 1621 without an heir, Isabel mournfully donned the habit of the Poor Clares. Her teenage nephew, King Philip IV, demoted her from sovereign regent to governor and assumed sovereignty of the Netherlands.

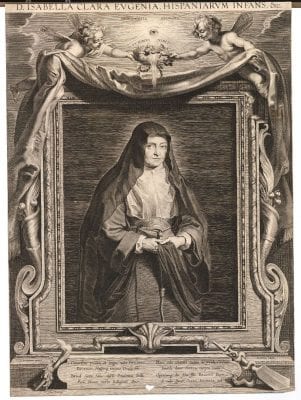

It had always been the infanta’s intention, were she to outlive her consort, to follow in the footsteps of her grandfather and father, who had withdrawn, respectively, to the Hieronymite monasteries at Yuste and El Escorial at the end of their lives, and to return to Madrid to retire to the Descalzas Reales. After Albert died, Isabel professed her vows as a tertiary of the Poor Clares and from that moment on wore only a rosary and the dark gray habit of the order (fig. 9). Despite taking this measure, her dream never came to pass. Isabel decided to stay in the Netherlands as it was the dying wish of her husband, she explained, that she continue to safeguard the future of the Netherlands and to ensure that it remain Catholic and loyal to Spain.

Under her new title as governor, the infanta’s opportunities to pursue an independent course of action were few. The demotion meant that she lost control of her war budget and was no longer allowed to set domestic or foreign policy.19 Moreover, Philip IV added new restrictions on Isabel’s authority in 1621, when he reestablished the Council of Flanders, the advisory committee dedicated to the governance of Flanders that Philip II had dissolved in 1598 out of respect for the archduke and duchess.20 In sum, she could no longer tackle the problem that most deeply vexed her realm: war.

The Siege of Breda

Infanta Isabel chaffed so strongly against the restrictions on her authority that in August 1624, when she was presented with the opportunity to attack the rebel Dutch forces in the town of Breda, she sanctioned the assault against the wishes of the king’s council. Her decision to attack Breda, an important garrison for the Dutch military, earned Isabel the criticism of Philip IV. Until that time the army of Flanders had made little decisive progress in the war with the United Provinces. Following the expiration of the Twelve Years’ Truce, a series of campaigns from 1621 to 1624 that failed owing to casualties, desertions, lack of funds, and the sheer superiority of Dutch military outposts had weakened Madrid’s confidence in Isabel and her general, Ambrogio Spinola, and led Philip IV to decree that the infanta report to his Council of State on matters of martial strategy.21 The restrictions were an extension of the broader limitations Isabel had been forced to endure since being demoted from the post of sovereign regent. Nevertheless, despite instructions from Philip IV that Spinola no longer pursue offensive strategies, Isabel sanctioned the attack on Breda.

Upon learning of the assault, Philip and his key advisor, the count-duke of Olivares, panicked in anticipation of the financial toll the venture would incur.22 Breda, located in the northern tip of the province of Brabant, represented an enormous tactical challenge for Spinola’s army. Herman Hugo’s Obsidio Bredana (1626), an eyewitness account of the siege composed within months of its end, describes how the town’s sandy soil meant that the army of Flanders could not dig tunnels under Breda’s defenses to level them with mines.23 The marshes that surrounded the garrison also challenged Spinola’s ability to limit access to the town and, thereby, the rebels’ ability to gather reinforcements. Finally, the Dutch had stocked the town with such substantial provisions that they could withstand a lengthy siege even though they were outnumbered by more than 50,000 soldiers.24

The strategic difficulties at Breda meant that the confrontation would become an exercise in siege warfare, a notoriously costly means of obtaining victory. As Luc Duerloo has noted, the problem with sieges is that they require an army large enough to completely isolate a town, enough artillery to continuously attack its barricades, and a substantial cavalry unit to deflect relief attempts.25 The army of Flanders possessed few, if any, of these resources. In October 1624, three months after Spinola began the siege, the king admonished the infanta and implored her to end the assault.26 She did not, and for nine months Spinola and his army laid siege to the town of Breda.

As the siege dragged on and prospects looked dim, Isabel stood behind her general, who insisted the town could be won. She secured additional horse- and footmen from the Holy Roman emperor after Spinola wrote that the Dutch had received reinforcements from Germany, France, and England.27 When the brutal winter threatened the health of the soldiers, she “gave order that six hundred course gownes for Centinells should be made, the better to be able to watch in the open ayre.”28 She also ordered “shooes and stockins, to the number of eight hundred.”29 Under these arduous conditions, the siege persisted. Then, on June 5, 1625, Corpus Christi day, the Dutch capitulated. The conquest was optimistically believed to signal a turning point in war against the Dutch, and Isabel, who had ordered the siege, rejoiced, perhaps not least because of the auspicious date of the Dutch surrender.

A week after the surrender, coverage in the weekly newspaper of the Habsburg Netherlands, the Nieuwe Tijdinghen, recorded the infanta’s triumphant entry into Breda, where the soldiers greeted her in grand fashion:

The whole army stood in battle order in open field, the first she passed being 8 regiments of foot, who fired 3 salvoes. Then there stood 140 companies of horse, who also fired three salvoes, and the town fired 3 salvoes with all the batteries, and the field guns, so that the earth shook . . . that night there were triumphal celebrations in Breda, and they lasted for 3 days.30

Isabel also distributed 110,000 guilders in cash to the victorious soldiers.31 Further, she commissioned a range of ex-votos, or gifts of thanks to God, all related to the Eucharist, believing as she did that she had secured the victory through her prayers to the Holy Sacrament. Indeed, in a letter she wrote to Fray Domingo de Jesús María, the head of the Catholic mission in Rome, upon her return from Breda, she called the victory “the great favor Our Lord granted us,” and described her gratefulness for God’s favor as so strong that she could never thank him or Our Lady of Victory enough, even if she thanked them “at every moment.”32

In his Obsidio Bredana, Hugo, who was Spinola’s personal chaplain, confirms that Isabel had prayed “continually” to God to gain the city.33 He describes how she had spent several hours a day in private prayer in addition to commissioning and participating in a continuous prayer before the exposed Sacrament lasting forty hours, known as the Forty Hours Devotion.34 Consequently,

it was the common voice of all, that the Infanta by her perpetuall prayers, and those of her court, and of other places by there continuall prayers in the fortie houre prayers to be made in all the Churches, and by powring out her almes amongst the miserable wonne Breda, and not with weapons. And truly divine succours were more present, then human stratagems, none can denie: for to whom shall we refer this benefit received, but to her so well known pietie. [emphasis in original]35

Immediately following the Dutch surrender at Breda, Isabel initiated the first of her many ex-votos to express appreciation for God’s gift of victory. From the Latin, ex voto suscepto (from a vow made), ex-votos are offerings to a saint or to God for redeeming a vow and are given in gratitude for divine deliverance. To thank God for answering her prayers for victory, she made arrangements in Breda for an annual commemorative Mass to honor the Eucharist and funded the building of a Capuchin convent and Jesuit college there (both were orders particularly devoted to the Eucharist). She also founded the confraternity of the Immaculate Virgin in Brussels, and, finally, she commissioned Peter Paul Rubens to design The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madird.36

Choosing the Descazlas Reales

Infanta Isabel’s gift of The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry cycle to the convent had several aims. First, it allowed her to honor a place and religious community she held dear. During her childhood, Isabel resided at the convent and spent long hours playing games in its cloister and gardens.37 She used its royal apartments as a personal refuge during the hot summer months–times when Philip II would retreat to El Escorial–and also during times of personal sorrow. It was where she went to mourn the death of her father in 1598.38 The Descalzas Reales also held significance for the infanta as the burial site of her mother, Elizabeth of Valois.39 As we have seen, Isabel’s affection for the convent and the pious life it offered her so profoundly appealed to her that she professed as a tertiary member of the Poor Clares the day after her husband’s death.

Giving The Triumph of the Eucharist to the Descalzas Reales, where religious life centered on Eucharistic worship, also allowed the infanta to express her abiding devotion to the Holy Sacrament. Like all members of the Habsburg dynasty, she believed fervently that it was her duty to protect and celebrate the sanctity of the Eucharist. According to Habsburg legend, Rudolf I (1218–1291), the founder of the Habsburg dynasty, was on a hunting excursion in the year 1264 when he came upon a priest holding the viaticum and walking to give a dying man his last rites. Rudolf, who was then a count, instantly dismounted his horse and offered it to the priest out of devotion to the Eucharist. Struck by Rudolf’s great piety, the priest prophesied that he and his kin would eventually rule over the world. Nine years later Rudolf became the first Holy Roman emperor. As Anna Coreth has noted, “in this conception, the Habsburg monarch was consecrated king through the Holy Eucharist itself.”40 On account of this legend, the Habsburg family believed that it enjoyed the Lord’s sanction, and that God had chosen the family to defend the holiness of the Eucharist from nonbelievers and to commemorate its majesty at all times.

At the archducal court in Brussels, Infanta Isabel and Archduke Albert elaborated on this task by generously supporting the Premonstratensian (Norbertine) priory of St. James-on-the-Coudenberg and the confraternity of St. Ildefonso, both of which were staunch defenders of the doctrine of transubstantiation.41 They also staged elaborate processions throughout Brussels during the feast of Corpus Christi that centered on a reliquary containing three bleeding hosts, said to have miraculously bled after having been profaned by Jews, an event known as the Holy Sacrament of Miracles.42 During these celebrations, the three relics, enriched with costly ornaments and jewels, lavish hangings, silk flowers, and three jewel-encrusted crowns and a mantle, were carried through the streets to the delight of the enormous crowds that gathered to witness the procession. Sir Charles Somerset, an English Catholic who went to Brussels in May 1612, described the festivities in his travel diary:

The famousest thing in this towne of Brussells is the Blessed Sacrament of miracles, which was by a Jew stabbed in derision of it, and instantly there gushed out blood, and this is now kept there in the chiefe Church of the town, & everie Corpus Christi day it is carried with great devotion in procession over all the towne, the Duke & the Infanta accompanying of it all the time of the procession. [emphasis in original]43

According to the “Record of the virtues of the Most Serene Infanta by the Discalced Carmelites nuns of Brussels,” on one particular procession of the Holy Sacrament of Miracles Isabel refused all defense against the hot sun. When they warned her that the heat would be too intense, her faith in the protective powers of the Eucharist supposedly led her to declare, “on this day, the sun does no harm.”44

Isabel actively continued to promote her devotion to the Eucharist during her widowhood. Not only did she profess as a tertiary member of the Poor Clares, but she also financed the construction of religious houses particularly devoted to the Eucharist, and supported confraternities committed to the Forty Hours Devotion. According to the Carmelite nuns of Brussels, on her deathbed her devotion was so strong that “when the viaticum was brought to her, for although mortally ill she knelt down on her bed as soon as she saw it brought in.”45

When Infanta Isabel presented her gift of The Triumph of the Eucharist cycle to the Descalzas Reales, it therefore not only allowed her to fulfill her duty to God but also to honor the convent she held so dear and to partake in a dynastic tradition of Eucharistic worship. At the same time, while the gift was technically to the Poor Clares, the message of the tapestries was directed at the king of Spain via his participation in the Good Friday and Corpus Christi celebrations.

The Matter of Audience at the Descalzas Reales

Founded in 1557 by Infanta Juana of Austria (1535–1573), the youngest daughter of Emperor Charles V and widow of King João Manuel of Portugal (1537–1554), the Descalzas Reales was deeply entwined with the royal court. Given its central location in Madrid, it had become the nucleus of religious life for all Spanish Habsburgs. Once Philip II declared Madrid the official location of the court in 1561, Habsburg devotional activities in the city centered at the convent church, which effectively functioned as a court chapel. It was there that the king made additions to the liturgical calendar, announced the canonization of Spanish saints, hosted public rituals (such as autos-da-fé), and celebrated feasts that involved dynamic, visible processions like the Forty Hours Devotion, the feasts of the Immaculate Conception, and, importantly, Good Friday and Corpus Christi.46

The king also met regularly with important visitors to Madrid at the Descalzas Reales. In addition to holding audiences at the Alcázar with princes, ambassadors, diplomats, and other foreign dignitaries, the king expected these heads and servants of state to visit him at the convent. Upon their arrival, they would have been brought to him on a route that took them through the reliquary room–a space that boasted hundreds of relics, stacked floor to ceiling, in lavish reliquaries composed of precious metals and inlaid with jewels and other costly materials.47 Surrounded by this tangible evidence of Habsburg devotion, the king’s guests were meant to understand, in no uncertain terms, the connection between his spirituality and his divinely ordained sovereignty. Because the Spanish monarchy believed that it had been divinely summoned to rule and actively promoted that notion, these highly public rituals and ceremonies were not simply religious. They were also political. They reinforced the relationship between God’s will and Habsburg power. The crown’s legitimacy rested on its divine sanction, its spiritual devotion, and connection to God. Thus, the Descalzas Reales helped the Spanish monarchy affirm its political agenda.

The king’s presence at the Descalzas Reales during political and religious events, and particularly during the feasts of Good Friday and Corpus Christi–the only events during which The Triumph of the Eucharist series would have hung–is an important (if long-overlooked) consideration underlying Isabel’s decision to donate the series to the Descalzas Reales. As Isabel would have known from experience, the Poor Clares sat behind a grille that separated them from the nave during the celebrations when The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestries hung in the church (fig. 10). The royal family, on the other hand, would have sat in a tribune in the nave designed especially for them in accordance with court etiquette. Although there is no extant correspondence between Isabel and Rubens regarding the design of The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series, there is little doubt that the infanta would have recounted this detail regarding the matter of royal spectatorship to her dear friend and favorite artist. Thus, when Rubens designed the Solomonic iconography and conceptual conceit for the cycle, transforming the space into a new temple of Solomon, he would have understood that although the nuns were the recipients of the series, the prime audience was the king — the very man who had demoted Isabel from sovereign to governor, forced her to govern by a committee of his appointees, cut her war budget, questioned her military decisions, and restricted her ability to generate policy.

Solomonic Ambition in The Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

Understood within this context, the Solomonism of The Triumph of the Eucharist cycle must have operated as an expression not only of religious devotion but also of political ambition. By presenting tapestries to the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales that resurrect the temple of Solomon in a new Christian identity through the tapestries-within-the-tapestries, Isabel Clara Eugenia identified herself as a sacral architect, a Solomon-like figure able to communicate with God and transform a space into a temple of His design.

Rubens reinforced the Solomonic reference through the illusionistic architecture from which the feigned tapestries hang: five of the eleven tapestries-within-the-tapestries are suspended from Solomonic columns. Characterized by a spiraling, twisted shaft, they refer to the twelve columns the emperor Constantine is said to have retrieved from Solomon’s temple in the fourth century A.D. and brought to Rome to be installed in St. Peter’s basilica. Their presence in St. Peter’s sanctified the basilica as the “New Temple” and, thereby, Constantine as the new Solomon.

Rubens utilized these columns to similar symbolic effect in two other large-scale commissions: The Life of Constantine tapestry series (1622) and The Life of Marie de’ Medici series (1623–25). Appearing in The Baptism of Constantine, where they surround the baptismal font, and in The Proclamation of Regency (fig. 11 and fig. 12), where they frame Marie de’ Medici on her throne, the Solomonic columns establish a visual and, therefore, symbolic link between rulers seeking to legitimize their authority and the archetype of wisdom and authority. In the case of Marie de’ Medici, who had only recently reconciled with her son, Louis XIII, after he exiled her for failing to relinquish the regency of France, the need to assert a right to power was of utmost importance. Surrounding her throne with Solomonic columns established her as the seat of wisdom in the manner of (a female) Solomon.

Rubens’s implementation of the Solomonic columns in the Marie de’ Medici series resonates particularly strongly with their use in The Triumph of the Eucharist series for the infanta Isabel, another female ruler eclipsed by the next generation of royalty. He had only recently concluded his work on the de’ Medici series when he was summoned to The Triumph of the Eucharist project, and he would surely have recognized the similarities of Marie and Isabel’s situations. Yet, the need to promote the infanta as a female Solomon may have been even more pressing in The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry cycle, which was, after all, a gift for a royal audience rather than, in the case of Marie de’ Medici, decoration for her own residence.

The importance of the Solomonic function of the cycle is nowhere more evident than in the panel depicting The Defenders of the Eucharist, where, at the center of the composition, the infanta is portrayed in the guise of Saint Clare (fig. 2). The image is almost certainly based on the portrait Rubens painted of the infanta in the wake of the victory at Breda (fig. 9). As the story goes, the day after Isabel Clara Eugenia returned to Antwerp from her triumphant entry into Breda, she called on Rubens in his studio where he “drew her picture, crowned, in a most Maiesticall fashion, with a laurell of victory.”48 Rubens pictured Isabel at knee-length, wearing the ash-colored habit of the Poor Clares, against a neutral background.

The portrait, which is today known only through copies and prints, has neither accompanying drapery, nor architecture, nor even any accessory, except for the rosary that hangs from her simple rope belt, thereby emphasizing her piety and spiritual authority. Rubens enhanced this concept by lightening the area around Isabel’s head as if she were radiating a divine glow. Barbara Welzel has noted that this halolike aura conveys Isabel’s majesty and plays with her second name, Clara, which in Spanish can mean light, thus visualizing a connection between the infanta and her moniker.49 An engraving after the painting with an inscription by Jan Gaspar Gevartius provides deeper specificity of meaning (fig. 13):50

of the imperial dynasty and daughter of Philip II, is praised as the jewel of Spain and the salvation of Belgium. She is the prudence of just war, the honor of chaste peace, and the love of religion. She was crowned with the oak wreath after capturing Breda, bringing the longed-for peace to Belgium, the peace it had sought in the rays of the shining Isabella.51

The text unmistakably credits the infanta for the victory at Breda by calling her the “jewel of Spain and the salvation of Belgium” and the one responsible for capturing the town. That the peace was also sought in her shining rays of light further links the victory to her spirituality and heavenly empowerment. The centrality of this sentiment surfaces in the divine eye of Providence that Rubens illustrated at the top of the portrait print, above the inscription “providentia augusta ut serves vincis” (You conquer because you serve sublime Providence). The symbol of God’s guidance and intervention, the eye presides over two supple putti who crown the infanta with “the oak wreath after capturing Breda,” a wreath, which, in Roman tradition, was awarded to those who had liberated their fellow man from a subjection imposed by the enemy. The wreath, thus, came to symbolically identify the person thus crowned as a savior. This image reinforces the notion that God watches over Isabel, and, through the spiritual authority he invested in her, helped her combat his enemies at Breda to secure the victory and bring “the longed-for peace to Belgium.”

Rubens’s conceptualization of the infanta became well known across Europe. Both the print and painting were replicated and disseminated widely. Fourteen copies of the painted composition by artists in Rubens’s circle, including one by Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), are known today, and although the patronage of these works cannot be confirmed, their distribution among the collections of royal houses suggests that Isabel Clara Eugenia was instrumental in their diffusion.52

In its connection to the triumph at Breda, the inclusion of the infanta’s portrait in The Defenders of the Eucharist was therefore not simply an image honoring Isabel’s role as patron of the series or her decision to profess as a Franciscan tertiary, but it was also one deeply connected to her political persona. Pictured among six male saints in a tightly crowded space enclosed by two large Tuscan columns under the radiant glow of the Holy Spirit, she proudly brandishes a monstrance housing the Host. The gesture references both a Solomonic and a dynastic tradition: she is shown possessing privileged access to the Holy Sacrament, as Solomon had to the tabernacle in the temple of Jerusalem, and as her father had to its counterpart, the Holy Sacrament, in El Escorial.

Even though Rubens pictured the infanta in the center of The Defenders of the Eucharist panel, it is noteworthy that he also situated her behind the figures of the male saints. Having painted for royalty and regents throughout his career, Rubens was sensitive not only to the needs of the patron but also to those of the viewer. He understood well the multiplicity of meanings inherent in iconography and would have recognized that by pushing the infanta into the background he could both assert her claim to power while also showing her willingness to subordinate herself to male authority–a highly diplomatic gesture given the likely location of the tapestry within the convent.

With the exception of one oil sketch in Chicago that shows Rubens’s intentions for the wall containing the grille of the nun’s choir (fig. 1), there are no known records that detail the specific arrangement of the tapestries in the church, a matter that has occupied scholarly debate for decades.53 However, Ana García Sanz has proposed a highly persuasive installation plan that is not only iconographically logical but that also works perfectly with the dimensions of the space (movie 1/ fig. 14-17).54 In her proposed layout, The Defenders of the Eucharist would have hung adjacent to the right of the main altar of the church (fig. 16). The nave of the convent church is only about 9.5 meters wide and royal tribunes were typically elevated. Thus, when King Philip IV bore witness to the Eucharistic ceremonies he would not only have been surrounded by the long-since destroyed Holy of Holies, here reshaped into its new Christian form, but he would also have been face-to-face with the woven visage of its great patroness, Isabel Clara Eugenia (movie 2). Gazing out from his lofted tribune, Philip would have stared out onto the triumphal carts and wagons celebrating the triumph of the Eucharist, and straight into the eyes of Infanta Isabel. By conflating Isabel with Saint Clare, Rubens reminded King Philip IV of her closeness to the Sacrament, her sacred power, and her Solomon-like, God-given authority. By keeping her in the background, he nevertheless assured King Philip of her loyalty to the crown. If only in surrogate form, Rubens proved that Isabel Clara Eugenia was, indeed, both “the jewel of Spain and the salvation of Belgium.”

Conclusion

There is little question that Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens conceived of the Solomonism in The Triumph of the Eucharist in the service of the Infanta’s political agenda. She commissioned the tapestry cycle after she had recently been demoted from sovereign regent of the Spanish Netherlands and in the aftermath of an important military battle she won, after having been told not to pursue. By calling on the imagery of the Jewish Tabernacle, Rubens likened Isabel’s abilities as a capable and divinely empowered leader to those of the fair and wise Old Testament king whose judiciousness and connection to God paved the way for a Golden Age of peace and unity.

Isabel, no doubt, intended for Philip IV to recognize this connection with the Old Testament monarch when he sat in his tribune, surrounded by the tapestries that “recovered the ancient, long since destroyed Holy of Holies [emphasis in original]” of the Old Temple in a new Eucharistic identity.55 She must also have hoped that the exemplary analogy would persuade her nephew to imitate Solomon’s legendary wisdom and good judgment, particularly in his future dealings with her, as their relationship had been fraught with distrust for many years. The tapestries’ messages of her divine support, capable leadership, and sage judgment presented Philip IV with a model for harmonious union. They showed him a roadmap for a future working relationship in which he would wisely empower her, as had God. She in turn would ably carry out the duties of her station. In this way, the imagery of The Triumph of the Eucharist series metaphorically announced Isabel’s suitability to govern the Netherlands with a freer hand than her nephew had previously allowed. Aligned thus with a venerable past, Isabel had begun to reestablish a politically authoritative present.