The Flemish artist Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts (late 1620s–ca. 1675) is known for his trompe l’oeil paintings depicting the easels, tools, and materials of an artist’s studio. In this essay, Gijsbrechts’s representations of ground layers and canvas preparations depicted in paintings produced during his four-year stay as a court painter in Denmark are compared to his actual working practice through visual and scientific analysis. Fifteen paintings by Gijsbrechts in the collection of SMK – National Gallery of Denmark were analyzed using visual examination, optical microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDXS) analysis. The study revealed that although Gijsbrechts often depicts dark red ground layers in his works, he typically painted on double grounds, consisting of a lower red ground layer followed by a second, lighter brown or gray layer. The results are set against works by other artists and their depictions of painters’ studios.

Introduction

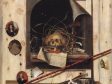

One of the most important trompe l’oeil artists of the seventeenth century, the Flemish painter Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts (late 1620s–ca. 1675) was active in Denmark between 1668 and 1672 as a court painter to the Danish kings Frederik III (1609–1670) and Christian V (1646–1699). During his four years in Copenhagen, Gijsbrechts created at least fifteen trompe l’oeil and vanitas still life paintings specifically for the Perspective Chamber, the first room in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer at Copenhagen Castle.1 These works, along with another five that Gijsbrechts painted in Copenhagen, form part of the collection at SMK – National Gallery of Denmark.2 Gijsbrechts’s unsurpassed mastery of trompe l’oeil (French for “deceive the eye”) is especially evident in his illusionistic paintings depicting the easels, tools, and materials of an artist’s studio.3 Recurring elements of these paintings—palettes, bundles of brushes, spatulas, jars for cleaning brushes (known as a pinceliers), glass bottles with oil, maulsticks, and unframed paintings with primed tacking edges—relate to the artistic process, as in Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1).

This essay explores the presence of ground layers depicted in Gijsbrechts’s trompe l’oeil paintings. While a close study of Gijsbrechts’s paintings leads to questions such as why he chose to reveal ground layers in his studio compositions, and whether this element played a practical or visual role in achieving the trompe l’oeil effect, the central focus here is on what this detail reveals about Gijsbrechts’s own painting practice. Taking a twofold approach, this essay first examines his painted representations of ground layers, which are visible along the edges of unframed paintings depicted in his compositions, seeping through to the verso of those canvases, and in his depiction of one unfinished painting in particular.4 Second, it contextualizes these observations by comparing them with Gijsbrechts’s actual use of colored grounds, to the extent that this can be determined from scientific analyses conducted on his works. Consequently, this essay investigates whether Gijsbrechts’s representations of ground layers reflect his actual painting practice.5

The characteristics of the ground layers in Gijsbrechts’s paintings—such as color, stratigraphy, and pigment composition—were investigated in fifteen paintings by analyzing paint samples using optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray analysis (SEM-EDXS). To obtain the best possible comparison between the colors of Gijsbrechts’s ground layers, the average color values of the layers in the cross section images were identified using image-processing software. The analyses aimed to examine the stratigraphy, colors, and pigment composition of the preparatory layers in his works.6 The samples, collected and embedded in resin during previous conservation treatments, were re-photographed according to a standard imaging protocol for cross sections developed by the National Gallery in London to ensure a more consistent basis for comparing the colors of the layers.7 The average color value of the individual ground layers on the cross-section images was defined by numeric L*a*b* (lightness, green/ red, and blue/ yellow) values, using the open-source image processing software Nip2 (fig. 2).8 The average color values were used to organize, visualize, and compare the ground layers in a systematic way, arranging the colors by increasing L* (lightness) values in three main color categories: brown, brown-red/ orange, and gray (fig. 3), as well as by lower and upper ground layer colors (fig. 4). The individual colors were assigned a simple color term (gray, brown, brown-red, and orange) in three grades: light, mid, and dark.9 Each ground layer was analyzed separately by means of SEM-EDXS to identify the elemental composition of the layer.

In the seventeenth century, an artist’s practice was typically shaped by a number of factors: the technical skills learned from his master, the geographical location where the artist worked, the influence of travels, and, not least, the availability of materials. Studying the development of a particular technical aspect of painting—like grounds—therefore requires extensive data from objects and sources from different periods and regions, as this special issue demonstrates. However, investigating an individual artist’s practice at a specific point in their career, as this study attempts, is only possible when comprehensive material evidence is available from a specific period and geographical area, which is not always the case. The fact that such information is available for Gijsbrechts’s four-year sojourn in Denmark provides a unique opportunity to explore both consistency and variation in Gijsbrechts’s production and technical ability at a specific point of his career.

Gijsbrechts and His Copenhagen Production

Evidence about the life and training of Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrecht is sparse, though it is presumed that he was born in Antwerp in the late 1620s. He married in Antwerp in 1648 but, presumably because of the death of his wife, he was listed as a member of the Sodaliteit van de bejaerde jongmans (Sodality of the Unmarried Men of Age) in 1659. Between September 18, 1659, and September 18, 1660, he was registered as a wijnmeester (son of a master) in the Guild of St. Luke in Antwerp.10 Gijsbrechts was an itinerant painter, active in the German cities of Regensburg and Hamburg in the 1660s before arriving at the Danish court in 1668, after being summoned by Frederik III.11 With his highly developed, transferable skills, it is likely that he left his home country for financial reasons, an “economic migrant” in search of the benefits of lucrative opportunities like employment as a court painter in Denmark.12 His court employment is documented in the royal accounts between March 19, 1670, and March 26, 1672, during which time he appears as den brabrandske maler (the Brabant painter ), receiving payments for stycker (pieces) and skillerier (paintings) on several occasions.13 Because the latest date found on a painting from his time in Denmark is 1672, it has been suggested that Gijsbrechts most likely left Denmark in that year.14

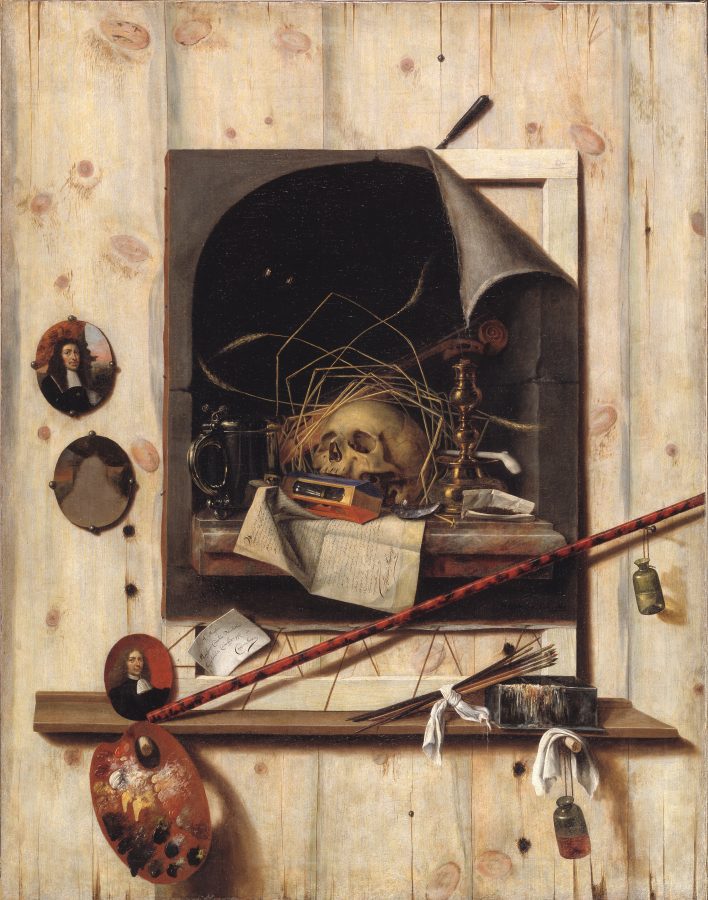

Gijsbrechts was a master of trompe l’oeil, a subgenre of still-life painting aimed at deceiving the observer into perceiving the two-dimensional surface of a painting as a three-dimensional object or collection of objects. Out of a surviving oeuvre of approximately seventy works, the collection at SMK holds twenty paintings by Gijsbrechts. These range from trompe l’oeil compositions featuring letter racks, musical instruments, and falconry equipment to vanitas still lifes. A highly deceptive variation are his depictions of the versos of paintings and so-called “artists’ studio walls.” Common to many of Gijsbrechts’s works is a painted illusion of a densely arranged surface that mimics or includes elements from the workspace of a painter (see figs. 1 and 6). The scene is often set against a backdrop of wood paneling, which presumably imitates pine wood based on its light yellow tonality; this was a low-cost material to which tools and shelves could easily be affixed, with the flexibility of rearranging the items according to need. In Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life, the pine paneling appears to function as a flexible wall easel with vertically arranged holes in the wood and pegs to hold the shelf in place at the required height (fig. 1). We can only speculate whether pine paneling was present in Gijsbrechts’s own workshop, which was located in the King’s Garden near Rosenborg Castle.15 He may have been inspired by Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678), who resided in Regensburg more than a decade before Gijsbrechts. In the early 1650s, Van Hoogstraten had depicted boards of light-colored wood as a framing device in his Trompe l’oeil Still Life of a Letter Rack with a Rosary and Playing Cards (fig. 5).

Research by Eva de la Fuente Pedersen argues that a significant number of these works were produced during Gijsbrechts’s four-year stay in Denmark and were specifically intended for the Perspective Chamber in the Kunstkammer.16 In addition to the Royal Chamber accounts from 1670 to 1672,17 a 1690 inventory mentions “twelve nice pieces with numerous figures by Cornelio Gübsbrecht” under the heading Perspektivsalen (Perspective Chamber).18 Nearly a century later, in his 1748 publication on Copenhagen, the Danish architect Laurids de Thurah (1706–1759) describes the Kunstkammer and mentions Gijsbrechts’s paintings: “One also sees here a Number of Paintings executed skillfully in Perspective; and several others with still-laying Objects, as the Painters call it; these latter are especially by a renowned Master, namely Gybrect.”19

Between Realism and Artifice

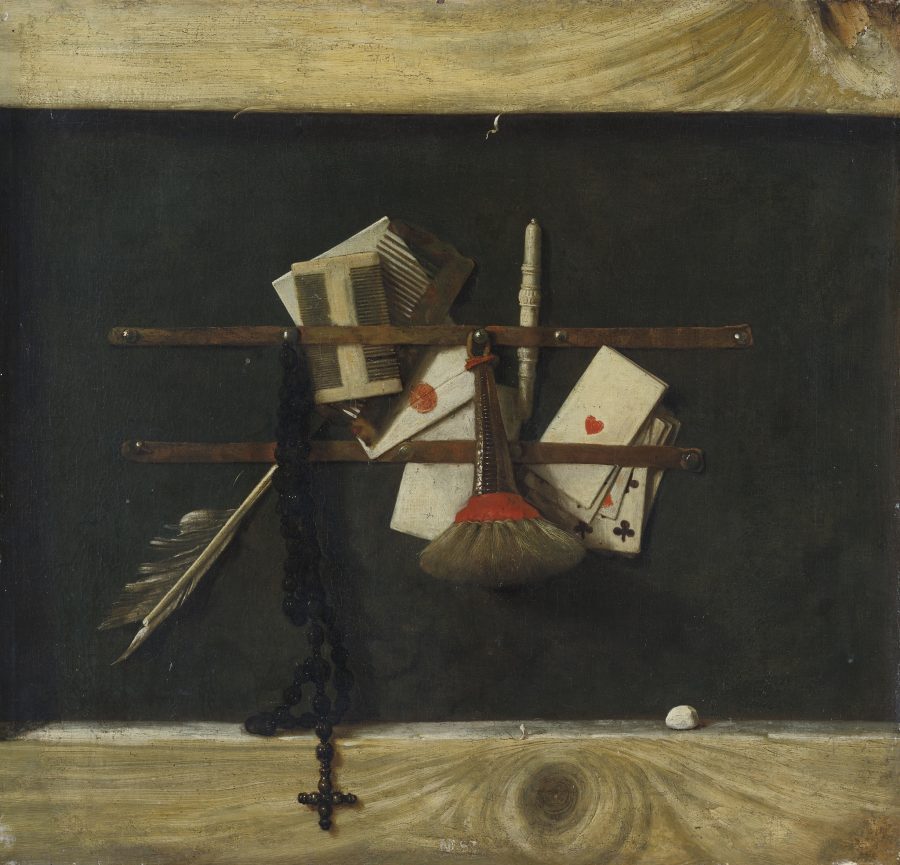

In his paintings of artists’ studio walls, Gijsbrechts provides the viewer with insight into the practice of a seventeenth-century painter. He frequently depicts artists’ tools, such as palettes hanging from the easel with dripping paint, maulsticks and brushes, glass bottles with oil, smudged paint boxes, wiping cloths, pigment powder, and palette knives. In Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1) and Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio (fig. 6), the objects are carefully placed and lifelike in their appearance, but the arrangement of the individual items does not always appear to reflect reality. For instance, a freshly prepared palette hangs vertically from the easel, allowing the light-colored paint to drip and mix with the darker colors (fig. 7).

An actual artist would not have allowed for this, as the dripping and unintended mixing of paint would result in a waste of costly materials and the labor put into grinding the pigments in oil. While painting, the artist would have positioned the palette horizontally, thereby preventing the risk of contaminating neighboring colors.20 Similarly, it appears illogical to place a palette with fresh paint directly adjacent to a finished painting, as in Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio. This exemplifies how Gijsbrechts, despite his predominantly realistic depiction of objects from the artist’s workshop, does not always arrange them in accordance with studio reality. A similar gray zone between realism and artifice is present in Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life. There a painting is depicted on a ledge, with its canvas stretched to a strainer using two distinct methods. Along the upper edge and on the sides, a mounting with nails is shown, imitating a typical final treatment for mounting a canvas painting on its strainer. Along the bottom edge, however, Gijsbrechts paints the canvas temporarily stretched with cords, a typical setup during the painting process. A painting in progress would usually be stretched in such a temporary working frame, with cords laced through holes along all four edges and placed on an easel, as illustrated in Pieter Jacobs Codde’s (1599–1678) A Painter in His Studio, Tuning a Lute (fig. 8). While this is not an impossible scenario—if, for instance, an artist did not have a well-fitting temporary strainer—it is nevertheless a surprising combination of stretching methods.21 A closer look at Gijsbrechts’s depictions of painted grounds in his compositions reveals yet another intersection of realism and artifice.

Gijsbrechts’s Depiction of Unframed Paintings

The paintings included in this study depict three distinct ways in which Gijsbrechts represents ground layers in his compositions. First, he paints unframed paintings with a red ground layer along the edges, as seen in Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1 and fig. 9) and in Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio (fig. 6). In the latter, two stretched but unframed paintings face the viewer—a landscape leaning against a reversed painting and a flower still life on a shelf above—with their tacking edges depicted as though a red ground layer has been left visible (fig. 10). This ground color is similar to the one seen on the edges of the unmounted painting depicted in Trompe l’oeil: Board Partition with a Still Life of Two Dead Birds Hanging on a Wall (fig. 11). There, a painted canvas mounted with nails on a wood-paneled wall shows exposed canvas along the edges and a reddish-brown ground layer underlying the rest of the still life. The painted canvas is detached from the pine paneling in the upper left corner and folded over, showing the verso of the fabric, its edges slightly lighter in color than the area in the middle. Gijsbrechts has even depicted how the ground of the still-life has penetrated into the fabric.

While the unprimed edges of the depicted painting in Trompe l’oeil: Board Partition with a Still Life of Two Dead Birds Hanging on a Wall suggest a canvas that was primed after being cut to its final format, the absence of cusping contradicts this conception. These wave-shaped deformations—typically caused when a canvas is primed while it is stretched with cords—do, however, appear along the lower edge of the depicted canvas in Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1). A different mounting with nails is seen along the left edge of the vanitas canvas in the same painting, where Gijsbrechts paints a red ground layer covering the entire tacking edge. This could indicate a commercially prepared canvas cut from a larger piece before mounting. Gijsbrechts depicts a similarly ambiguous stretching in the related work, Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life, in the collection of Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes.22

Gijsbrechts’s Depiction of Reversed Paintings

All of the paintings mentioned previously (fig. 1, fig. 6, and fig. 11) depict canvases primed with dark brown-red grounds. This color recurs in compositions where paintings placed back to front are depicted, showing the verso of the artwork. These depicted paintings exemplify the second way that Gijsbrechts illustrates ground layers in his works: by painting how traces of ground material can seep through the weave of the fabric during application and become visible on the back of the canvas. While the depiction of such details emphasizes the material characteristics closely linked to the period’s practice of priming a canvas, they only illustrate the first ground layer, applied directly to the canvas, as a second ground layer would not seep through.

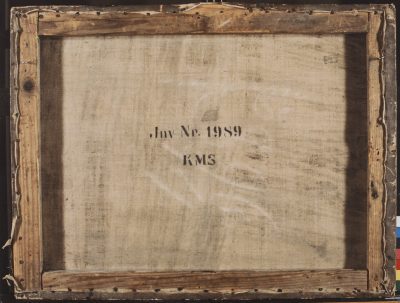

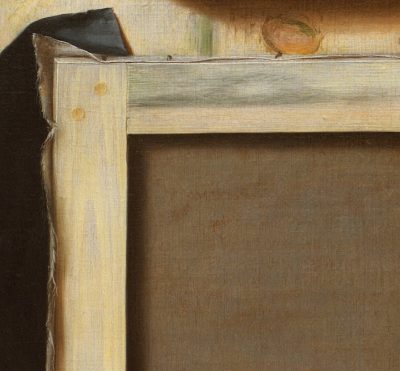

In Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting (fig. 12), the entire object is an imitation of a reversed painting: a canvas mounted on a strainer and secured in a frame with six nails. The strainer is depicted with a half-lap join secured with three wooden dowels in each corner, while frayed canvas edges are rendered between the strainer and the frame. This illusion closely resembles the actual back side of this very painting, including the construction of the original strainer and the stretching (fig. 13; the original strainer, now preserved in the archives of SMK, was replaced by a new stretcher during conservation treatment in 1979). The original strainers of paintings by Gijsbrechts at SMK are made from pine wood that is similar to the imitation wood paneling seen in his compositions.23 Some of these strainers were likely produced by carpenter Hans Balche, who in 1669 supplied Gijsbrechts with no fewer than thirty-three strainers.24 During past restoration treatment of Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting, it was observed that the canvas was originally affixed to the back of the strainer with nails—as seen on the image of the back side before treatment—rather than along the edges, which would have been standard practice. A similar stretching and mounting structure has been observed in other works by Gijsbrechts, such as Trompe l’oeil with Riding Whip and Letter Bag, depicting a paneled wall with riding equipment.25 This suggests that some paintings may originally have been intended to be presented without a decorative frame in order to increase the illusionistic effect even more.

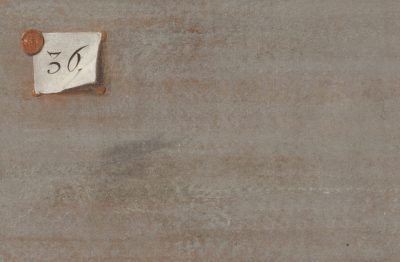

In Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting, the illusionistic composition includes a fictive frame, depicted with nails holding the strainer in place. Along the frame’s edges, random strokes of black paint imply that its imagined front side would have been painted black. Gijsbrechts heightened this illusion by painting the tacking edges of the actual painting black, as the sides of the frame would have been. This reinforces the idea that the work was meant to be displayed without a decorative frame. In the upper left of the composition, Gijsbrecht has painted a small paper label marked with the number “36” in black, affixed to the depicted canvas with painted seals of red wax. The back of the depicted canvas appears gray, creating an illusion of a gray paint layer. In studio scenes by other artists, the backs of canvas paintings also appear to have a similar gray color—for instance, in Jan Steen’s (ca. 1626–1679) The Drawing Lesson (fig. 14), where a canvas painting leans against a chest in the foreground. A similar gray color can be seen on the reverse of a painting placed against the wall, behind the assistant preparing paint with a muller on a grinding slab, in Painters in a Studio by David Rijckaert II (1586–1642) at the Louvre (fig. 15).

A closer look at Gijsbrechts’s brushwork in Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting reveals that the gray verso depicted is no monochromatic gray but is rather composed of shifting tonalities of gray, white, and reddish brown (fig. 16). Gijsbrechts applied these colors with thick paint dabbed onto the canvas to achieve the illusion of a canvas structure, while sporadic highlights heighten the sense of texture. In Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio (see fig. 6), a reversed canvas painting leaning against the wood-paneled wall in the lower left shows a gray surface intermittently disrupted by dots of reddish-brown paint (fig. 17), similar to what can be observed in Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting.

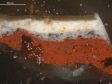

The red paint applied by Gijsbrechts in both Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting and Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio imitates a red ground material (as would have been applied to the front of the canvas) seeping through the interstices between the canvas threads—an effect often observed when a knife or a spatula is used to apply a ground layer with firm pressure. A similar phenomenon is depicted on the back of a canvas placed against the wall in Joost Cornelisz Droochsloot’s (1586–1666) Self-Portrait of the Artist in His Workshop from 1630 (fig. 18). Physical remains of ground material are not infrequently identified on the reverse sides of paintings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including the actual painting Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting, as noted during the restoration treatment in 1979 (fig. 13).26 In both Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting (fig. 12) and in Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio (fig. 6), Gijsbrechts appears to have imitated this effect by applying a gray paint layer somewhat unevenly, seemingly allowing the underlying red to shimmer through (see figs. 16 and 17). Unfortunately, it remains uncertain whether Gijsbrechts made the actual red ground layer in Trompe l’oeil: The Reverse of a Framed Painting shine through. Determining this would require a paint sample from the gray area, but existing samples come only from sections depicting the strainer and the frame.

In the painting Trompe l’oeil Studio Wall with a Vanitas Still Life from the Ferens Art Gallery (fig. 19), Gijsbrechts painted a detached corner, a feature similar to the loose corner in SMK’s Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1). In the Ferens Art Gallery painting, Gijsbrechts not only depicted a red ground layer seeping through the canvas, as discussed above; he also painted traces of priming material on the fictive strainer bar. This detail imitates how the red ground seeps through when it is applied to a canvas that has already been stretched. Similar to the detached corner depicted in Trompe l’oeil: Board Partition with a Still Life of Two Dead Birds Hanging on a Wall (fig. 11), Gijsbrechts included a color difference between the outer edge and the rest of the back of the depicted canvas. This aligns with observations of actual paintings; conservators often notice a color difference when paintings are removed from their stretcher or strainer during conservation. The edges, protected by the stretcher or strainer, remain brighter, while the uncovered areas fade and darken over time due to exposure to light and dirt. For Gijsbrechts, this type of detail enhanced the illusion of age, suggesting that time has passed between the creation of the works depicted in the compositions and the artist’s own time.

The third and final way in which Gijsbrechts depicts ground layers is exemplified by another detail from Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1). On the left, an unfinished oval miniature portrait is pinned to the wood-paneled wall (fig. 20). While the miniature’s landscape background and drapery appear complete, a monochromatic gray surface has been left in reserve for the still-unpainted figure. It remains unclear whether Gijsbrechts intended this gray to mimic a local gray underpainting or a gray ground layer. The latter would contrast with the dark red ground layers depicted in the previously discussed examples—if indeed these are meant to illustrate a single red ground layer—yet it aligns more closely with Gijsbrechts’s own practice of applying his paint layers on a light brown or gray second ground layer, as discussed in the next section.

Gijsbrechts’s Practice

The study of the grounds depicted in Gijsbrechts’s paintings raises the question of how faithful he was to reality in his illusionistic paintings—and, more precisely, whether his depiction of ground layers aligns with his own painting practice.

The examinations of fifteen paintings by Gijsbrecht with light microscopy and SEM-EDXS indicate that the artist generally used different methods to build up the grounds in his own paintings and to represent painted grounds within his trompe l’oeil compositions. Gijsbrechts preferred painting on colored double grounds, with a first layer ranging from dark brown-red to mid-brown in color, followed by a second layer with a light gray to mid-brown color (as illustrated in fig. 2). While the depicted ground layers in Gijsbrechts’s compositions instead tend toward dark red single ground layers, one instance stands out as more closely aligned with his actual practice: the miniature portrait in SMK’s Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life, which shows a gray monochromatic ground layer—unless, of course, this detail is intended to represent a monochromatic underpaint (fig. 20).

Three actual paintings by Gijsbrechts—with different motifs—contain a gray-over-red double ground, with the lower brown-red layer composed of red earth and calcium carbonate and the gray layer made of lead white, calcium carbonate, and a black pigment, of the type discussed in this issue by Maartje Stols-Witlox and Lieve d’Hont (figs. 21a, 21b, and 21c).27 Five other paintings, three of which depict riding and hunting equipment hanging on a wood-paneled wall, share an almost identical double ground structure with a thick first layer, dark brown-red in color, consisting mainly of red earth and calcium carbonate, followed by a thinner layer of a mid-brown color that includes primarily calcium carbonate, lead white, and red earth (figs. 22a, 22b, 22c, 22d, 22e). The visual similarity and close numeric color values of the ground layers of these five paintings suggest that their canvases may have been primed on the same occasion or cut from the same roll of commercially pre-primed canvas.28

The paint used for the darker brown-red lower ground layers identified in most of Gijsbrechts’s works consists predominantly of red ocher and calcium carbonate, with minor additions of lead white and baryte. The mid- and light brown second ground layers—often thinner than the first layer—consist mainly of calcium carbonate, lead white, and some red, yellow, or brown earth, occasionally with traces of aluminum silicates and quartz (fig. 2). This structure served a practical purpose: first, a thicker ground layer consisting mainly of low-cost earth pigments reduced the irregularities of the canvas texture, and second, the upper ground layer provided a lighter midtone for the paint layers. 29

Wood-paneled walls—light yellow in color—are depicted in thirteen of the paintings examined. In some works, this wall makes up a large part of the painted surface, as in SMK’s Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 1) and in Trompe l’oeil: Board Partition with a Still Life of Two Dead Birds Hanging on a Wall (fig. 11). In other works, such as Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio, this compositional element plays a relatively minor role (see fig. 6). In paintings where the light yellow wood walls take up a substantial part of the painted surface, one might expect that Gijsbrechts used a light-colored upper ground layer to serve as a midtone in the final painting. Surprisingly, however, he primarily worked on mid-brown or gray upper ground layers, even in the paintings that depict wood-paneled walls. The upper ground layer with the lightest color (of the fifteen paintings examined) was found in Trompe l’oeil with Breakfast Piece and Goblets, which includes no pine paneling and is an unusually somber composition, depicting a predominantly dark bluish-green drapery.30 These examples, along with a close visual examination of the surfaces of Gijsbrechts’s other paintings, suggest that the artist did not deliberately exploit the color of the ground layers by leaving it exposed in strategic areas.

Representation Versus Reality

As we have seen, the depicted paintings in Gijsbrechts’s trompe l’oeil compositions feature dark red edges that simulate the use of a colored reddish-brown ground layer (figs. 1a, 6a, and 11a). A similar dark red color is present in traces of ground material depicted on the verso of fictive canvas paintings or strainer bars, mimicking how the material from a first ground layer might exude through the canvas weave during priming (figs. 16a, 17a, and 19a). In the Freeness Art Gallery’s Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall with a Vanitas Still Life, Gijsbrechts even renders a canvas with traces of red ground material visible on the stretcher bar, as if it was primed while mounted on a stretcher. By contrast, other works represent different priming practices: in Trompe l’oeil: A Cabinet in the Artist’s Studio, Gijsbrechts depicts two unframed paintings with red priming extending over the tacking edges (fig. 10a), possibly alluding to commercially prepared canvases cut from a larger piece. SMK’s Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life depicts a combination of nails and cord used for stretching a canvas, with one tacking edge covered by a red ground layer and the lower edge left unprimed (fig. 9a).

Aside from the gray layer of the unfinished miniature in SMK’s Trompe l’oeil with Studio Wall and Vanitas Still Life (fig. 20), results from the technical analyses of Gijsbrechts’s works indicate that his recurring depictions of dark red grounds do not fully reflect his own practice. Analyses of paint samples from Gijsbrechts’s paintings reveal that, during his years in Copenhagen, he did not typically apply his paint layers directly onto a dark red ground layer, as suggested in his illusionistic compositions. Instead, he preferred to work over a light-colored brown or, in a few cases, a gray upper ground layer. Beneath this, as a first ground layer, we typically find a thicker dark red or brown ground layer composed primarily of less expensive earth colors and calcium carbonate, similar in color to the grounds represented in Gijsbrechts’s trompe l’oeil paintings (figs. 2a, 3a, and 4a). Gijsbrechts’s depictions of red tacking edges might more accurately reflect his own practice in the event that he applied the second ground layer only to the front of the canvas—after it was primed with a first red layer and mounted on a stretcher—however, conservation reports from past treatments of Gijsbrechts’s paintings at SMK contradict this practice, noting that the paint layers in several examples extend to cover the tacking edges.31 This suggests that the actual ground layers in these paintings were applied either before or while the canvas was stretched on a working frame with cords. The painted composition was then built up while it remained on the working frame, after which the canvas was mounted onto its final stretcher. If the second ground layer had been applied while the painting was already mounted on its stretcher, the final paint layers would not have extended onto the tacking edges.

The stratigraphy, color, and pigment composition identified in Gijsbrechts’s paintings were common at the time, as illustrated in the articles by Moorea Hall-Aquitania and Paul J. C. Van Laar, as well as Stols-Witlox and d’Hont, in this special issue. 32 Also, technical analyses carried out on canvas paintings by other artists active in Denmark earlier in the seventeenth century have revealed similar ground layer structures and include examples of dark red or brown layers used as a base for the paint layers.33 While some artists integrated the tone of their colored ground layers into the final composition in order to work more efficiently, Gijsbrechts’s use of red grounds appears to have been primarily pragmatic, serving as an inexpensive and flexible layer beneath a subsequent thinner but still opaque gray or light-brown ground, which he may have chosen or applied himself. It is evident from the paint sample analyses that he often applied light-colored local underpaint layers on top of his double grounds for his imitations of pine paneling. As a court artist, Gijsbrechts may have been less compelled to adhere to the demands of the art market than other artists who were not so advantageously situated. A painter working for the free art market might use a colored ground to work more efficiently and economically, by adding fewer covering paint layers. Gijsbrechts, however, does not appear to have adopted this approach. The fact that he received strainers directly from the carpenter Hans Balche suggests that Gijsbrechts stretched and prepared his own canvases in his workshop, allowing him to control all the steps of the painting process, including the final outcome.

Although the depictions of ground layers in Gijsbrechts’s trompe l’oeil paintings reveal some inspiration from his own practice—notably in the depiction of a brown-red first ground layer—an accurate reflection of painting practices (his own or others’) was likely not his primary concern. This argument is supported by the fact that other elements in his trompe l’oeil paintings, such as hanging palettes or the cramped arrangement of tools and materials, are represented in ways that clearly diverge from reality. It is unlikely that the audiences for Gijsbrechts’s paintings possessed enough familiarity with contemporaneous painting practice that they would have wondered about the accuracy of the depicted priming colors, application methods, or stretching techniques. It seems more likely that Gijsbrechts introduced certain details to create tonal harmony within the composition—for instance, by juxtaposing brown-red tacking edges with light yellow pine paneling, or the gray versos of canvas paintings with light yellow strainers. In depictions of canvases shown from the reverse, their gray tone not only establishes a visual and tonal contrast with the surrounding strainer and pine paneling, but it also convincingly imitates the appearance of a gray paint layer, even if the application of such a covering layer on the verso of canvas paintings was not common practice at the time. In the end, the discrepancies between Gijsbrechts’s own practice and the techniques he depicts in his compositions underscore that his trompe l’oeil details served pictorial harmony and illusion rather than factual accuracy, reaffirming his preference for representation over reality.