This article is concerned with melancholia, a disease of fashion in the early modern era, which was associated with qualities of genius, privilege, and piety. Focusing on melancholia’s contradictory humoral qualities, which instigated both heightened inspiration (heat) and depressed spirits (cold), this study maintains that artists exercised calculated iconographical choices in depictions of hermits and scholars, both melancholic archetypes. Specifically, painters reinforced medical tradition by the knowing use of botanical imagery to suggest melancholia’s ambivalent nature and the necessity of achieving humoral balance in its cure.

In the early sixteenth century, Aertgen van Leyden (1498-1564) painted the studious Saint Jerome seated in a shadowed interior space, lit only by the feeble glow of a candle (fig. 1). The holy man directs his gaze toward a skull, which he holds in his left hand, as he presses his other hand against his head in the time-honored pose of melancholia. Jerome’s shadowed face is composed in an expression of extreme dejection, his eyes half closed in sorrowful contemplation of death. He seems to inhabit an exclusive interior realm, from which he contemplates his great task and muses upon the vanity of human existence. Preferring solitude to the company of people, tested by God, and granted the gift of divine genius, Saint Jerome is a paragon of pious “enthusiasm,” or religious melancholy.1 The circumstances of Jerome’s life (321-420) contain most of the saturnine attributes that apply to the Renaissance melancholic persona.2 In his youth, Jerome was a devoted scholar, but a serious illness caused him to retire to the desert, where he did penance in solitude for several years and befriended the faithful lion, which would become his constant companion. Upon his return to the active world, the saint devoted his life to the service of the Church in the form of study, teaching, and writing, eventually becoming as famous for his scholarship as for his sanctity. Artists from both Italy and Northern Europe depicted Jerome traditionally in two ways – as a hermit alone in the desert surrounded by wild animals, sometimes battering himself with a stone, or as a pensive savant accompanied by the accouterments of scholarship. Beginning in the mid-fourteenth century, he appears as a solitary figure in what can be construed as a scholarly “study.” In subsequent centuries, Jerome’s extreme piety merged with the topos of the secular Aristotelian scholar. Both contexts – hermit and scholar – are consolidated in early modern botanical imagery, which enlarges and comments on these inherited traditions by means of empirical observation.

Melancholia: Derivations from Antique Theory and Christian Morality

Today the word melancholia connotes sorrow or depression, psychiatric conditions that are increasingly common in contemporary society. But before the nineteenth century, the condition was perceived as involving both body and mind and was considered as pervasive and dreaded as cancer and heart disease are today.3 Authorities blamed melancholia for any number of unsavory things, including mental depression, cholera, syphilis, witchcraft, and even murder. Criminals and sociopaths commonly succumbed, due to the influence of the dark planet Saturn. However, the dark planet could also stimulate deep thought and spark creative fires, bringing lovers, scholars, and saints into its realm. References to melancholia throughout history therefore express curious ambivalence – a combination of apprehension and reverence.

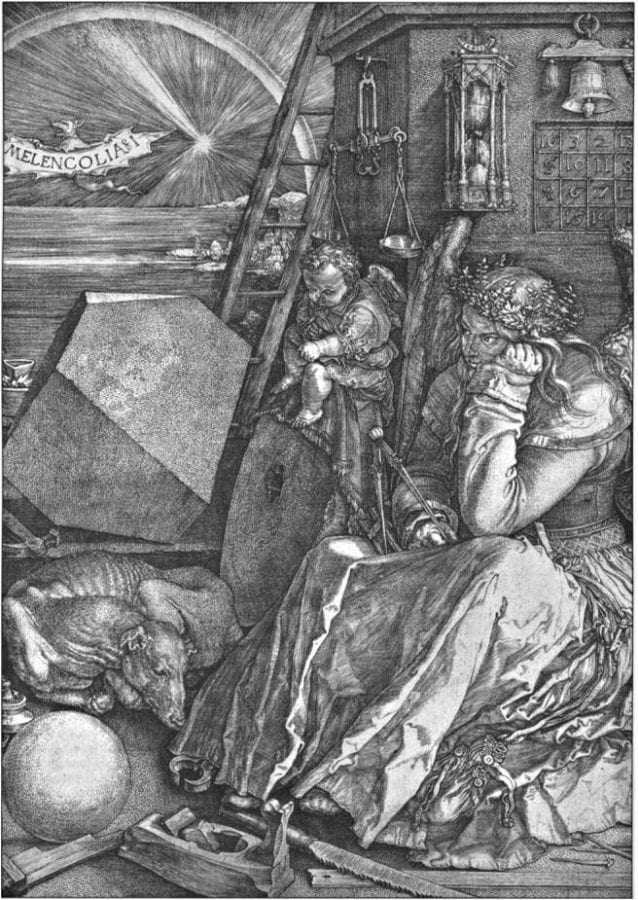

To art historians, the most familiar representation of melancholia is the secular engraving Melencolia I of 1514 (fig. 2) by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1526).4 The field of art history, enlightened and informed by Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl’s magisterial book Saturn and Melancholy, accepts Dürer’s engraving as the culmination of a philosophical tradition nearly two thousand years in the making.5 However, Melencolia I not only embodies the past but also stands at the beginning of a visual tradition that culminated in the mid-seventeenth century. For two hundred years, roughly 1500-1700, melancholia was a pervasive cultural phenomenon, perceived as a disease of fashion that connoted intellect and privilege. Its travails were part of a cultural vocabulary given form internationally in all branches of the creative arts.6

Before the scientific revolution, melancholia, in all of its physical and psychic ambivalence, was part of a system of beliefs that is no longer relevant to modern empirical thought.7 Humoral theory, which prevailed generally until the eighteenth century, was based on the simple belief that four qualities (hot, cold, wet, dry) and four elements (fire, air, water, earth) were the components of life, and all substances contained them in some combination.8 In the body, during the process of digestion, a syrupy, whitish substance called “chyle” was believed to be produced. When the chyle reached the liver, it was cooked, or “concocted,” into one of the four humors – yellow bile, phlegm, blood, or black bile. These humors performed specialized functions within the body. Blood, which contained the qualities of warmth and wetness, was associated with the element of air, and was “prepared” in the liver. From this organ, blood nourished the body, giving it strength and color. The kidneys and lungs produced cold, moist phlegm, whose purpose was to lubricate the body, especially the mouth. Yellow bile, dominated by choler, was hot, dry, and bitter. It functioned in the gall bladder to help regulate body heat and expel waste. The infamous black bile, which caused melancholia, was cold, dry, thick, black, and sour. Centered in the spleen, it nourished the bones.

The quartet of elements, qualities, and humors was commonly represented visually as four temperaments, or human types – the choleric (hot, dry, fire, yellow bile), phlegmatic (cold, wet, water, phlegm), sanguine (warm, wet, air, blood) and melancholic (cold, dry, earth, black bile) (fig. 3). These humoral quartets were divided into opposing camps: those which support life and those which were hostile to life.9 All people, the foods they ate, and the illnesses that assailed their bodies were ruled by a dominant humor and its associated qualities. An excess of one led to an imbalance that involved the entire body, though the illness might show itself in an isolated part. Physicians healed by introducing substances opposite in quality to the illness being cured. To this end, all substances from which medicines were made, and the illnesses to which they were applied, were rated on a sliding scale from one to four according to the degree of heat and moisture contained in them. Ultimately such efforts were designed to achieve the same end – to achieve health by establishing and maintaining harmony.

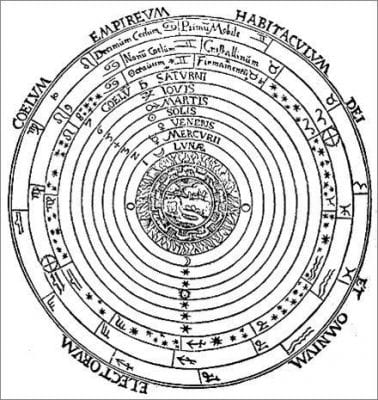

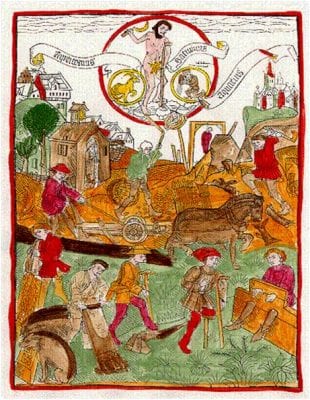

The humors and elements also claimed a celestial presence. In the Platonic earth-centered universe (fig. 4), as in the Copernican/Galilean heliocentric cosmos, the seven known planets were associated with specific humors, elements, and qualities.10 The twelve zodiac signs, the “fixed stars,” were in turn identified with specific planets. Each planet, with the exception of the sun and moon, claimed two natal zodiac signs, though their orbits allowed planets to visit each one as they traveled across the sky. The stars and planets controlled all life on earth through direct sympathies with the objects, people, and activities they ruled. The night planet Saturn was associated with black bile, earth, and melancholia. By association, the iconography of melancholia, therefore, includes references to time and measure (derived from Saturn’s origin in the legend of Kronos), cutting (Saturn’s scythe), and death (the planet’s slow orbit furthest from the earth). The astrological character of Saturn and the unhinged personalities of its children are vividly portrayed in the theme of the “Children of the Planets,” which was dispersed as a series of prints, beginning in the fifteenth century and continuing through the seventeenth century.11 Saturn’s page, one of seven from an early block-book (fig. 5), is typical in its placement of the planetary deity in the heavens above, accompanied by his two zodiac signs, Capricorn and Aquarius. Included among the children of Saturn on the earth below are cripples, suicides, and misanthropes, indicating a tendency toward anti –social, sometimes criminal activities. At home in their native element of earth, they also include honest, hard-working farmers and grave-diggers. In concert with the nocturnal feminine moon, Saturn ruled a dark, shadowed realm.

Melancholia boasted a venerable Classical pedigree. Its first documented mention is in the Aphorisms of Hippocrates, which describes the condition as caused by dyscrasia, or lack of harmony among the humors.12 The concept was transmitted through the ages by writings attributed to Hippocrates (late fifth century BCE), Plato (426-347 BCE), Aristotle (384-322 BCE), and Galen of Pergamon (131-201), which formed the core of the western European medical curriculum until the Enlightenment. Without exception, treatises describe symptoms that were as much psychic as physical – listlessness, slovenliness, loss of appetite, sleeplessness, depression, pallor, headache, chills, and mental delusions. These signs were described identically, regardless of the nationality of the writer, throughout two thousand years of history.

The Pseudo-Aristotelian “Problem 30,” now attributed to Theophrastus, integrated the Hippocratic medical notions of melancholia with Plato’s concept of divine frenzy, combining the qualities of madman, poet, and genius into a single definition.13 The Problemata posed the following question: ‘Why are all outstanding men in philosophy or politics or literature or in the arts obvious melancholics, and in fact some of them to the extent that they have succumbed to the symptoms which arise from black bile?’14 While not doubting that black bile could cause mental imbalance, Aristotle’s account also claimed that it generates great intellectual gifts, even the power of prophesy, in a condition referred to as ‘genial’ (deriving from the word ingenio) melancholy.15 In the end, Aristotelian melancholia was much like wine – exhilarating if tempered but dangerous if experienced in excess. A precarious balance between debilitating insanity and exalted genius existed in Greek philosophy, as melancholia could distinguish both states of mind.

The most notable theorist to revive the topos of the genial melancholic was the Florentine priest, physician, and neo-Platonist Marsilio Ficino, whose three-part treatise, De vita triplici (1489), is devoted to the symptoms and cures of melancholia.16 Although medieval astrological tradition placed scholars under the influence of Jupiter, Ficino attributed the qualities of inspired intellectual genius to Saturn. Born under a saturnine horoscope himself, Ficino echoed Aristotle in attributing the highs and lows of intellectual creativity to a sudden combustion of black bile within the body – the fire of inspiration. This happened often to those who attracted the attentions of Saturn because black bile was naturally as dry and brittle as wood, and just as flammable. Although the blaze itself could instigate a frenzy of creative activity, its aftermath was distinguished by the charred remains of burned humors and black smoke, which rose to the brain, causing inevitable psychic depression. Ficino maintained that this phenomenon was not limited to natural melancholics, those born under a saturnine horoscope, but could be induced by an inclination toward intellectual pursuits. Poets, artists, princes, and philosophers alike could therefore claim dominion by Saturn, regardless of accident of birth. By manipulating the things of the natural world, they could channel Saturn’s malevolent power toward creative inspiration and deep thought. In the tradition of the ancients, Ficino instructed melancholics to create an anti-saturnine microcosm by manipulating astrological talismans – herbs, music, and colors – so as to attract the moist, beneficent planetary influences of Venus, Jupiter, and Sol. Under Ficino’s influence, melancholia was worn like an exclusive badge by those wishing to associate themselves with material privilege and intellect.17 Ficino’s views were absorbed fully into the medical and cultural understandings of melancholia and were accepted unequivocally by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century authorities.

Christianity added a moral dimension to the authority of the ancients. As punishment for original sin, the humors were doomed to vie with each other for dominance within the body, causing the illness, pain, and death that universally afflict the human race.18 Behavior which ran counter to Christian ideals – carelessness, weariness, apathy, anguish, sadness, negligence – could therefore provoke humoral imbalance.19 The eleventh-century medical theorist Constantinus Africanus (1020-1087) noted, not without irony, that melancholia seemed often to afflict monks and hermits, as those who engaged in the devout pursuit of spiritual enlightenment were most likely to experience ‘intense fear of God . . . especially trying to solitaries.’20 He exhorted religious recluses to temper their devotions with careful monitoring of their daily lives, a task which the Benedictine rule, with its strict divisions of manual and mental labor, addressed admirably. Nonetheless, the physical privation experienced by holy men was augmented by psychic symptoms – visions, mystical revelations, and sometimes the gift of prophecy.

A dichotomy arose in the Christian tradition. On one hand, Saturn’s evil influence engendered sloth and misanthropy – sins in the eyes of the Church. Melancholia was perceived as both a moral and a physical disease, visited upon the world as the result of original sin.21 On the other hand, the saintly lives of hermits and monks predisposed them to the same behavior, though their virtue could not be questioned. The privileging of religious melancholy – the rapturous transports of prophecy and inspiration experienced by hermit saints and prophets – owed much to Socrates, who coined the Greek term ek-stasis to describe how the divine spirit enters the body of such men, causing their souls to become detached. The experience was akin to being literally transported “beside oneself,” in a prolonged, if deluded, state of intense bliss.22 The exaltation of such men derived from Aristotle, who linked creative genius with the state of enthousiastikon – meaning to be possessed, or inspired. Western theorists, from Constantinus Africanus onward, maintained that black bile was endemic to devout and saintly hermits, who experienced a kind of “divine ravishment.”23 Religious melancholia therefore took on the contradictory attributes of wretchedness and privilege that also distinguish its ancient prototypes. It became linked with the monkish duties of contemplation, prayer, and thought, occupations also characteristic of the gifted, yet tortured, secular scholarly melancholic.

Saint Jerome as Paragon of Piety and Intellect

In their rehabilitation of Aristotelian melancholia, Renaissance theorists demonstrated renewed respect for visionary enthusiasm and its links with extreme piety and hermetic deprivation.24 Early modern authorities viewed Christian moral tradition through the glass of antique Galenic medicine, which placed all aspects of Saint Jerome’s legend within the sphere of Saturn. By the sixteenth century, Jerome had become synonymous with the condition of scholarly melancholia. As a model of studiousness, he was the foremost example of an inspired Aristotelian intellectual within the Church hierarchy , and the patron saint of scholars. The biography of the saint, Hieronymianus, by the Bolognese humanist Giovanni di Andrea, was written in 1342 and published in 1511. This was followed by Erasmus’s publication of a completed edition of Jerome’s writings in 1516.25 It is debatable which came first – the intensified medical interest in melancholia or the renewal of the cult of Saint Jerome. In any case, the conflation of the two phenomena – one religious, the other scientific – inspired a wealth of images. These works of art, which span all media and all of Western Europe from the fourteenth through the seventeenth century, emphasize the dichotomous nature of religious melancholia. To put it succinctly, this was a condition brought on by extreme virtue, but which manifested itself in antisocial behavior. Its symptoms alternated between extreme heat and frigid cold. Its presence suggested both great joy and extreme suffering. Humoral theory provides a means of interpreting these ambivalent attributes in support of an elite identity, embodying qualities of both virtue and sociopathy, within the larger context of Saturn, melancholia, black bile, and earth.

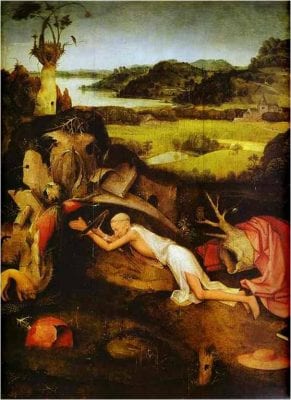

Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450-1516) favored his namesake Saint Jerome (Latinized as Hieronymus) above all.26 His Saint Jerome at Prayer in Ghent (fig. 6) communicates the virtues of self-denial, suffering, and visionary enthusiasm inherent in religious melancholy. It also summons the association between the cold, dry element of earth and the transports of saintly melancholia. In Bosch’s painting, the holy hermit has cast off his splendid red cardinal’s hat and robe and thrown himself upon the ground in a transport of religious rapture. His intense piety evokes the monastic ideal of deprivation and suffering, as he lies prone literally engulfed by his cave shelter. Saint Jerome is one with the earth, the element represented in humoral theory by Saturn, black bile, and melancholia.

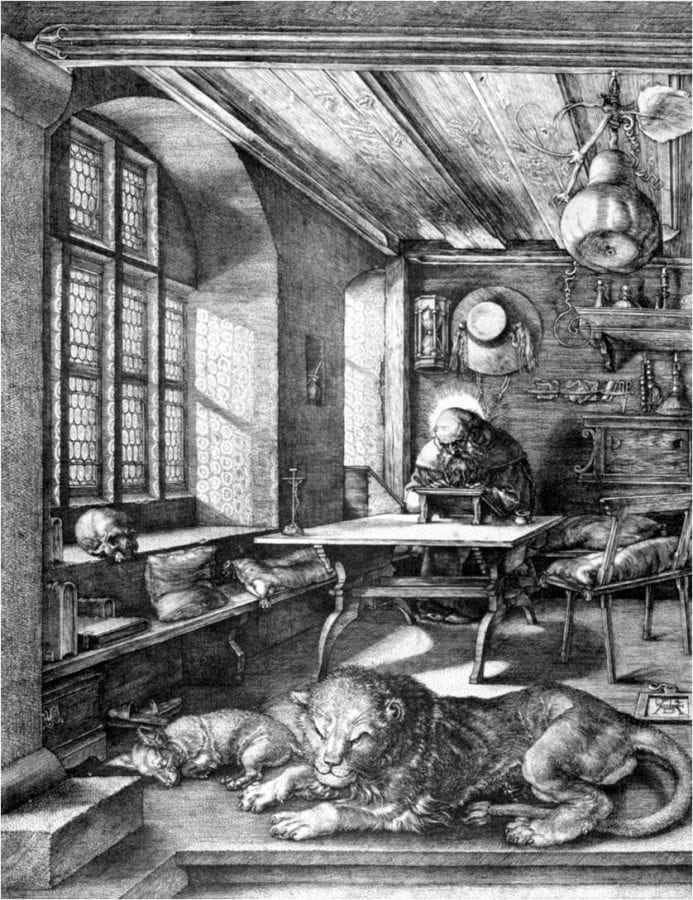

Albrecht Dürer’s many renditions of Saint Jerome also merge the qualities of piety and genius with knowledge of humoral theory. Dürer was fascinated with the person and legend of Jerome, portraying him at least ten times between 1492 and 1521. His most familiar rendering of the subject is Saint Jerome in His Study (fig. 7).27 Panofsky believed these three prints were intended to be seen as a related series, corresponding to Cornelius Agrippa’s theory of three ascending grades of melancholia. Saint Jerome would then signify “Melencolia III,” the highest “grade,” devoted to knowledge of divine secrets.28 However, Dürer’s diary, which recounts his well-documented journey to the Netherlands in 1520-21, indicates that the artist never grouped all three together as gifts, preferring to pair the Melencolia I and SaintJerome.29 It appears that the artist intended them as a duo, illustrating scholarly and religious melancholia. Visually, they share several common elements, including the sleeping dog, cutting implements, and time-measuring devices associated with the scythe of Saturn in the guise of Kronos.30

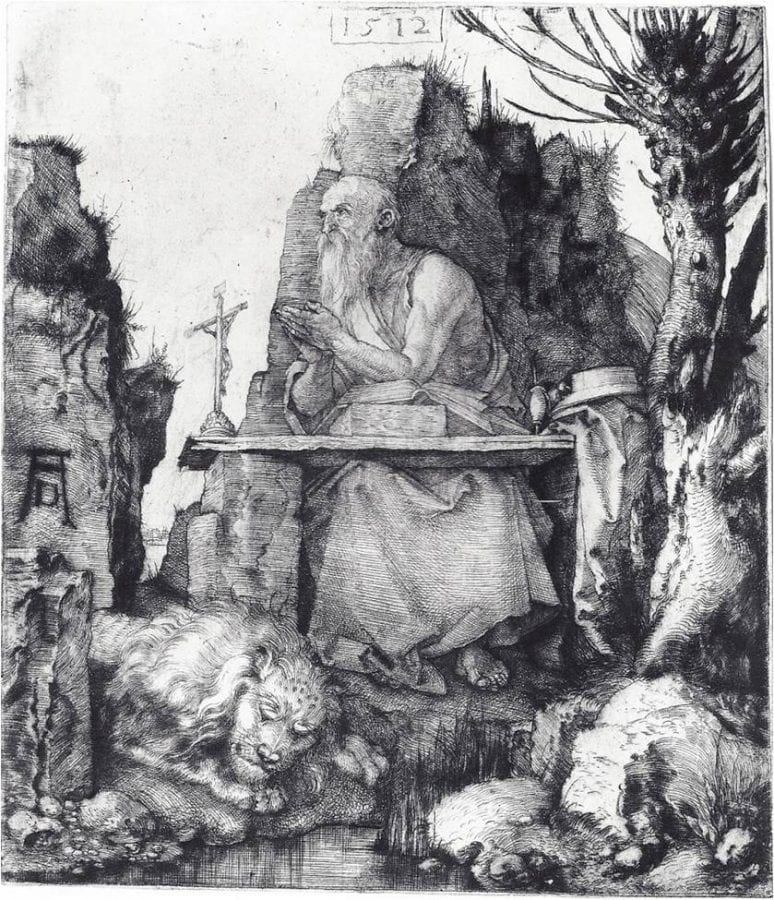

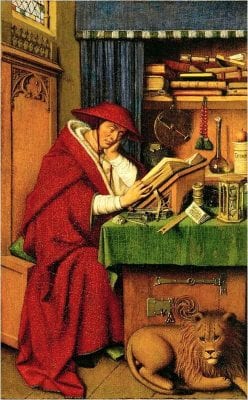

Dürer also favored the theme of Saint Jerome in the wilderness, apart from the comforts of his scholarly study. As in Bosch’s depiction, Dürer’s Saint Jerome by the Willow Tree (ca. 1512) (fig. 8) powerfully emphasizes the saint’s connection with the saturnine element of earth by enclosing him in an outcropping of rocky turf.31 Jerome’s body is visually fused with his stone sanctuary, an edifice that also serves as shelter, throne, and makeshift desk. In suggesting melancholia’s humoral signature, Dürer combined the two iconographic contexts of the saint’s legend – hermit and scholar – in a single image. As such, Jerome embodies both the solitary and misanthropic facets of the melancholic personality. In this print, as in others, Dürer was influenced by historical precedent, especially in the inclusion of medical references to the tribulations of melancholia. Nearly a century earlier, Jan van Eyck (or a follower) painted the saint in his study, posed head-on-hand (fig. 9).32 Among the tangle of books and papers in Jerome’s study are a long-necked medicine bottle and an apothecary jar labeled “Theriac.” This medicine, whose main ingredient was distilled snake venom, was valued both for its moral and medical powers.33 Like the talismanic wreath of watercress and mathematical square of Jupiter in Dürer’s Melencolia I, it functions as an antidote against black bile, symbolizing both spiritual and physical healing. Such references persisted in later interpretations of the hermit-saint theme, and their presence is entirely relevant to the ambivalent nature of melancholia as carrier of both privilege and debility.

The generic theme of the pious hermit was renewed in the Counter-Reformation age, when theologians supported a return to the rugged asceticism of the early Church fathers.34 A lively debate on the nature of enthusiasm occupied scholars throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and eventually involved such major philosophers as John Locke and Jonathan Swift.35 Religious reformers began to associate the condition with radical sects, whose members claimed special ecstatic powers through contrived convulsions and trances. Although the term enthusiasm came to be used pejoratively by some, its link with melancholia and the extraordinary abilities of biblical prophets and saints remained. Robert Burton’s encyclopedic The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621, includes “religious melancholy” among the various manifestations of the disease. In his discussion of enthusiasm, Burton, an Anglican vicar with no admiration for the fervent spiritual transports of Catholic hermits and martyrs, was skeptical, noting that “If you shall at any time see a religious person over-superstitious, too solitary, or much given to fasting, that man will certainly be melancholy.”36 Other seventeenth-century theorists questioned the transports of prophecy ascribed to enthusiasm.37 Meric Casaubon’s Treatise Concerning Enthusiasme of 1655, though skeptical of “holy inspiration,” still includes “divinatorie,” “contemplative,” and “precatory (praying)” enthusiasm among the five kinds of legitimate inspiration.38 Henry More’s Enthusiasmus triumphatus of 1565 recognizes enthusiasm as a form of melancholia but ascribes it to a disordered imagination, which produced a kind of “natural inebriation.”39 It is this “spiritual high,” achieved through bodily suffering in imitation of Christ, which informs early modern depictions of hermit saints.

Responding to the controversy, seventeenth-century painters continued to invest pious hermits with saturnine traits and symbols, though they often jettisoned traditional iconographic elements, such as Jerome’s hat and lion, which would identify him specifically.40 Artists may have stripped their works of specific hagiographical elements purposefully, in order to appeal across religious boundaries to both Catholics and Protestants.41 They also interposed plants, laden with herbal symbolism, to evoke the qualities of austerity and learning associated with melancholia.

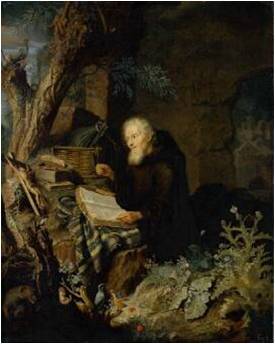

Gerrit Dou’s Hermit in Prayer of circa 1635 (fig. 10) is one of many such paintings of holy men, which were produced in great numbers in the seventeenth century.42 As in many other representations of hermits from this time, Dou’s hermit prays before a large, open book, presumably a Bible, in the confines of a secluded grotto. On the ledge before him are a skull and crucifix, clear allusions to vanitas, death, and the promise of Christian salvation. The lantern and straw pilgrim’s basket hanging above him recall the hermit’s continual search for enlightenment on his life’s journey. Although Dou’s holy man lacks the traditional iconographical attributes that would identify him as a specific saint, references to religious melancholia abound, particularly in the fore-grounded plants, which grow seemingly randomly across the floor of his cave-study. These are not the carefully cultivated tulips and roses, prized by gardeners and connoisseurs, which claim pride of place in the Dutch still-life tradition. They are rugged, wild, weeds which, despite the hardships of drought and frost, flourish untended in the countryside. They are suitable botanical parallels to the privation and hardship suffered by religious melancholics.

Although herbal symbolism had long been part of the artist’s iconographical arsenal by the time Dou painted the Hermit in Prayer, seventeenth-century painters demonstrate a new and prevalent familiarity with plants and their attributes.43 Their interest was paralleled by major advances in botany, evidenced by the great profusion of printed herbals, illustrated with brilliant images from life, that appeared at this time.These books, popular since ancient times, melded botanical lore, inherited from earlier traditions, with current scientific discoveries and accurate, objective representations. Herbals such as Otto Brunfels’s Herbarium (1530), Leonard Fuchs’s Historia Stirpium (1542), Rembert Dodoens’s Plantarum seu stirpium iconons (also published as Cruydt-Boek, 1544), William Turner’s New Herball (1551), and, the most encyclopedic of them all, John Gerard’s revised and enlarged Herball of 1633, were very popular. They all borrowed images and texts from each other in many consecutive printings and translations of herbals throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth century.44 Although the illustrations in herbals were based on empirical observation of actual plants, the format ultimately derives from Classical sources, specifically the herbals of Dioscorides and Rufinus. These beautiful and useful books not only illustrated and described every known plant, but also noted humoral affiliations, practical medicinal uses, and religious associations.

Melancholia’s contradictory humoral nature – negative and positive, hot and cold, active and passive – is implicit in the plants artists chose to depict in scenes of hermits in the wilderness. In fact, specific plants were known to be especially effective in obtaining the bodily and emotional equilibrium essential for maintaining health and curing disease. Ficino, echoing ancient humoral theory, counseled that “by a frequent use of plants . . . you can draw the most from the spirit of the world, especially if you nourish and foster yourself by things which are still living, fresh, and all but still clinging, as it were, to mother earth.”45 This advice, inherited from the ancients, was echoed by all herbal authorities in succeeding centuries.

In Dou’s scene, as in many others, the large, leafy plant growing in the right foreground of the cave joins Saint Jerome’s roster of attributes as a sign of saintly melancholia. The specific herb pictured by Dou appears frequently in seventeenth-century depictions of hermits and is also included in most printed herbals of the time, where it is described as “great water dock” (fig. 11). A common plant, which still grows abundantly in the low-lying areas of Northern Europe, the dock is a member of the genus Rumex and is related to the plant familiar to modern viewers as rhubarb (fig. 12). Gerard’s massive herbal, which synthesizes material from earlier sources in many languages, labels this plant Hippolapathum sativum,” and describes it as tall, with leaves measuring from one to three feet long. The accompanying text notes that “the Dutch men name this herbe . . . patientie . . . or Monkes Rubarbe” and indicates that the great water dock is cold in quality and valued medicinally “‘against the stinging of serpents.”46 In paintings of devout hermits, then, water dock’s legendary effectiveness is linked with the theriac cure first alluded to by Van Eyck. Its effectiveness against snakebite recalls original sin, initiated by Satan in the guise of a serpent. Dock’s cold humoral affinity also negates the heated passion of lust, the temptation that assailed Saint Jerome in his seclusion.47 The plant’s epithet, “patience,” reinforces the quality of constancy in adversity, a necessary Christian virtue cultivated by all pious folk. For Dou’s hermit, the monk’s rhubarb serves as a botanical ally in his battle against temptation.

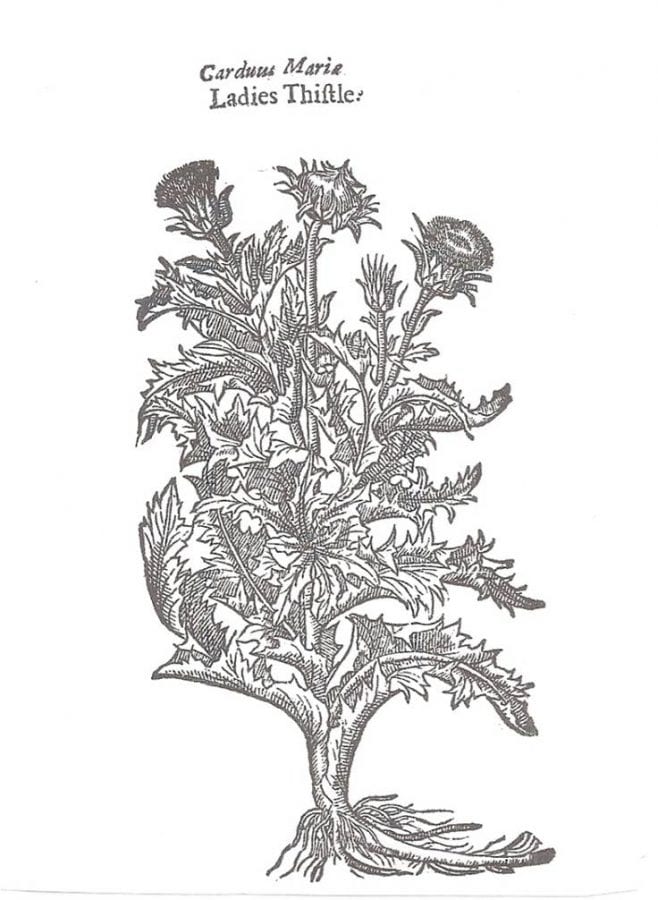

References to the moralistic and medical iconography of plants and animals are more numerous in Pieter Leermans’ s Hermit Scholar of circa 1680 (fig. 13). Although the artist omitted the obvious Catholic elements of Jerome’s iconography, the identification of this praying hermit as the scholar-saint is reinforced by the animals and plants that accompany him. An array of plants cluster in the right foreground of Leermans’s scene. Here are the large, curling leaves of the water dock, which signifies, as in Dou’s painting, the virtue of patience in the saint’s battle against temptation. To its right is a thistle, another herb whose iconography is relevant to Christian virtue and healing (fig. 14). Gerard’s text illustrates several varieties, one of which corresponds to the plant in Leermans’s painting. “Our Ladies-Thistle” (fig. 15), so named because the milk of the Virgin supposedly stained its leaves, was believed to have prophylactic properties against poisonous animals, especially when worn about the neck as an amulet.48 The plant appears prominently in other representations of pious hermits and was favored by Dou. In Leermans’s scene, a small toad, traditional symbol of evil and putrefaction, appears in the rounded hollow formed by the meeting of thistle and dock leaves, in the lower right corner of the scene.49 Compositionally, the creature’s evil influence is visually prohibited from entering the saint’s space, as its poison is kept at bay by the prophylactic powers of both plants. Because humoral theory designated thistles as hot and dock as cold, the herbal duo incorporates strength within its partnership, providing the balance of opposite qualities essential for health.50

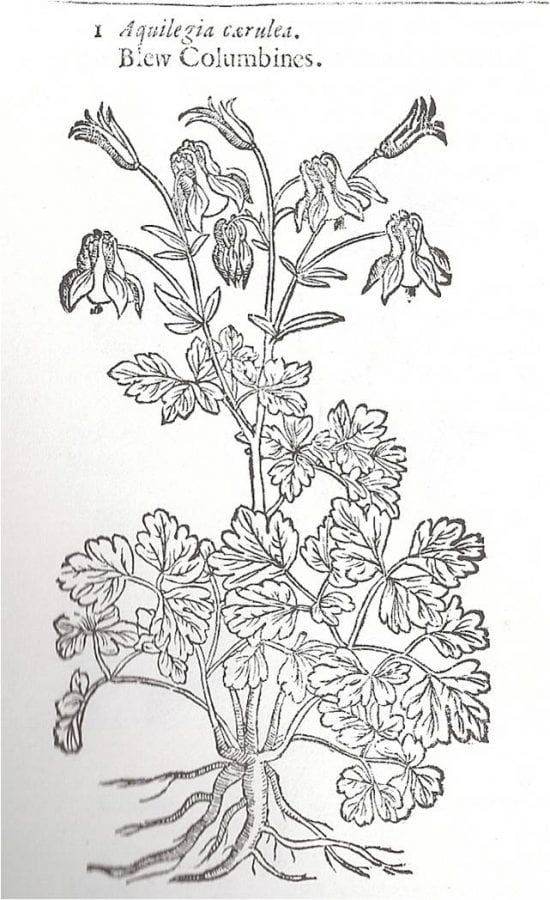

Yet another significant, identifiable plant flourishes in the saint’s garden grotto. Situated just to the left of the water dock, growing among several other blooming wildflowers, is a columbine (figs. 16 and 17), distinguished by several drooping blue flowers on a graceful stalk. As a traditional symbol of sorrow (named agley or akeleyen in Dutch, ancolie in French), the columbine often represents the sorrows of the Virgin.51 Here, it designates Saint Jerome as a victim of chaste and pious melancholia. Herbals rated this flower “temperate between heat and moisture”; thus, it serves as an intermediary between the extremes of heat and cold in the hermetic wilderness.52

Dou’s and Leermans’s hermits are depicted as generic paragons of piety, not as specific saints. Rembrandt’s renditions of Saint Jerome are exceptions to this strategy.53 As an artist who often borrowed earlier traditions in his works, Rembrandt (1606-1669) retained the traditional symbols associated with the saint from the beginning. His print versions of the theme reveal a deep sympathy for the torments of saintly enthusiasm, which derived from his profound understanding of the iconography of Saturn and melancholia.54 Born and briefly trained in Leiden, Rembrandt could not help but be familiar with the prevailing debate on the subject.55 Interest in all aspects of melancholia predominated in the medical curriculum at the university there, where forty-nine doctoral dissertations on melancholia were produced in the last half of the seventeenth century alone, eighteen of them during Rembrandt’s lifetime.56 The actual number of dissertations on the subject, more than produced at any other European university, was probably even larger, as doctoral candidates were often allowed to substitute a written examination for the dissertation requirement. The implication, recognized by historians of medicine, is that the subject of melancholia gained dramatically in importance during these years, especially in the Netherlands.

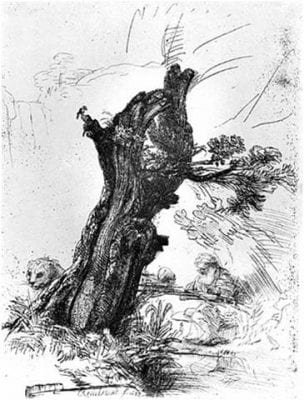

Rembrandt’s etching Saint Jerome Beside a Pollard Willow of 1648 (fig. 18) masterfully alludes to the physical and spiritual suffering of Jerome in several ways. Here the bespectacled holy man is neither praying nor pummeling himself with stones but working studiously, accompanied by the steadfast lion. The omnipresent skull and cardinal’s hat rest nearby. A gnarled, leaning pollarded willow serves as Jerome’s improvised writing desk, sheltering him from above with one jutting, flourishing branch. The pollarded willow tree, which also appears in Dürer’s drypoint of 1512, had, by the seventeenth century, become standard fare in renderings of hermits in the wilderness. But in Rembrandt’s etching, the large, weathered tree is more carefully rendered than the figure of Jerome himself and commands our attention as the dominant focus of the scene. Its barren trunk and live branches have been interpreted as a reference to Christian resurrection and to the tree of knowledge of good and evil that once grew in the Garden of Eden.57 In later centuries, willow trees came to be associated with mourning as Romantic symbols of death and tragedy. Medicinally, however, the willow was prized since ancient times for its medicinal effectiveness against pain, fever, and inflammation. In fact, the common modern drug aspirin was initially derived from a distillation of willow bark.58 Just as it does for modern sufferers, the tree’s palliative powers soothe Rembrandt’s Saint Jerome in his solitude. Its legendary iconographical association with sorrow further reinforces his suffering in both mind and body, which are both implicated in saintly enthusiasm. The willow joins the monk’s rhubarb, lady’s thistle, and temperate columbine, which flourish, despite man’s neglect, in Jerome’s hostile wilderness.

The pollarded willow tree in Rembrandt’s print serves an additional function as well. Although less common today than in the seventeenth century, this type of purposeful controlling of a tree’s growth is still practiced (fig. 19), and such trees are part of the distinctive Northern European landscape even today. The process involves drastic cutting back of branches to the main trunk, resulting in dense growth at the cutting point, which as a result becomes bulbous and knarled.59 Theoretically, by rigorously controlling a tree’s growth, it is strengthened. The large, contorted trunk and gnarled protrusions of Rembrandt’s willow represent an extreme example of the effects of this especially punishing form of pruning. The disfigured, amputated willow struggles to stay alive despite repeated obstacles to its growth, assuming the role of a botanical embodiment of the tortured body and anguished spirit of the hermit saint. But the disfigured tree still manages to produce a single leafy branch, which arcs above the head of Saint Jerome, suggesting the unfettered growth of his mind and spirit. Like the pollarded willow, Jerome endures continual suffering, becoming stronger through self-denial and continuous ‘pruning’ of his fleshly desires. In company with the pollarded willow, he endures the hardships of the ascetic life, even as he demonstrates the discipline and piety required to withstand its rigors.

The Scholar as Melancholic

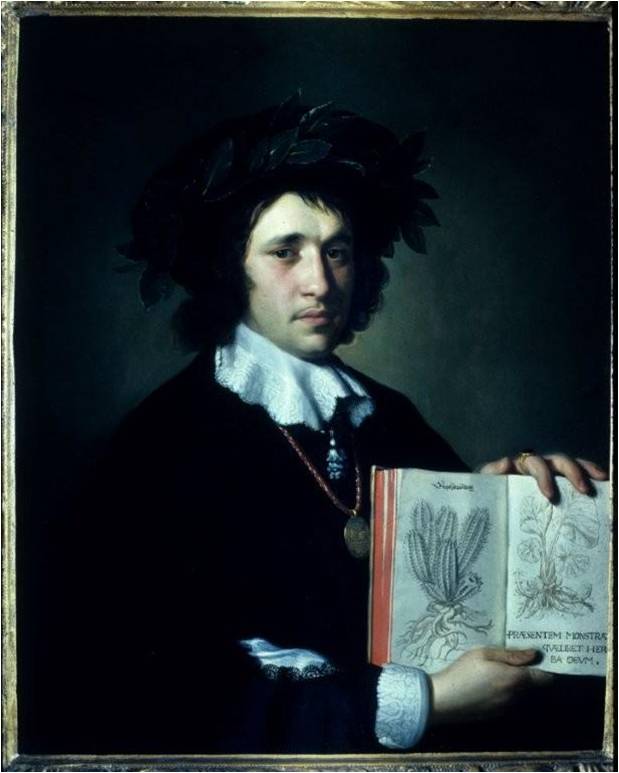

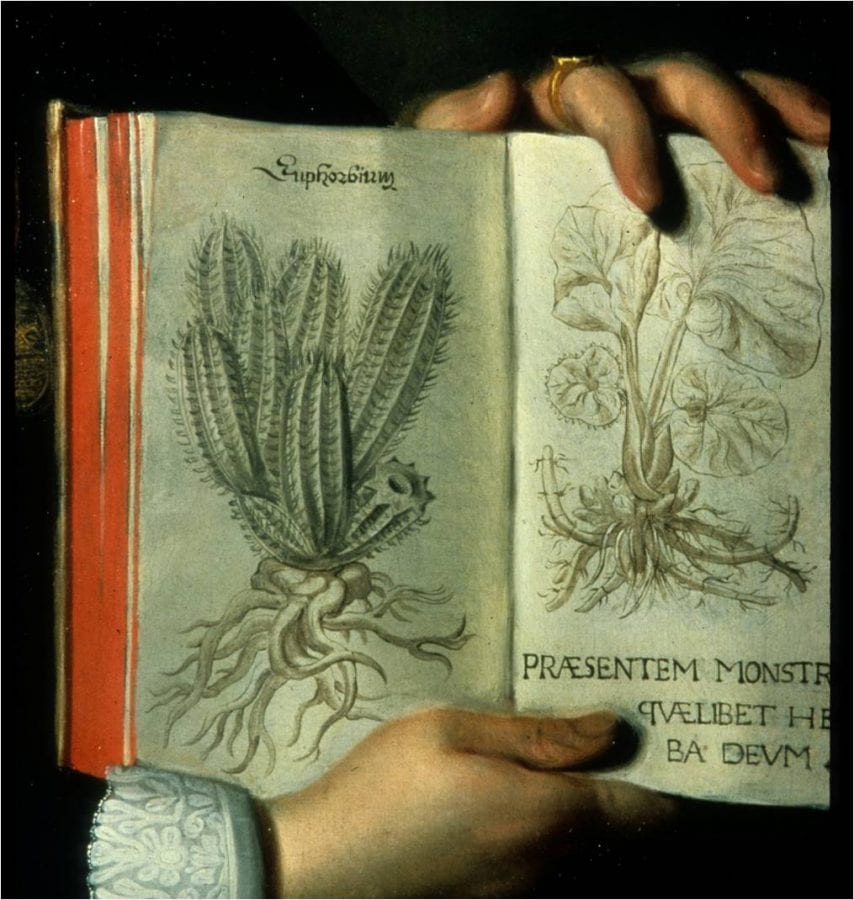

The ambivalent character of melancholia, alluded to in the botanical environments of hermit saints, was transmitted to the theme of the scholar in his study, a popular subject for seventeenth-century artists. Botanical imagery, with its references to suffering, piety, and intellect, was one of many ways of suggesting the privileged passion of Aristotelian scholarly genial melancholia. But it is the interpretive focus in Portrait of a Scholar (1647) by Willem Moreelse (ca. 1620-1666) (fig. 20), which portrays a pale young man, whose tired eyes and furrowed brow express the disquieting sense of distress associated with black bile.He wears distinguished academic regalia, consisting of a black cloak with slashed sleeves and a soft, round academic bonnet entwined with laurel leaves, of the type worn by new doctors.60 Moreelse’s youthful academic is evidently a recent graduate of the university at Utrecht, for he wears around his neck the promotion medal given to successful doctoral candidates, engraved with the coats of arms of the city and the university.61 He directly engages the viewer’s eyes while exhibiting an open book, revealing clearly discernable images of two herbs: one a prickly, tubular plant with intertwined roots, labeled “Euphorbium”, the other a plant with large, spade-shaped leaves and multiple, hairy roots (fig. 21). The latter is not accompanied by an identifying label, but by an inscription, “praesentem monstrat quelibet herba deum” (Any herb shows the presence of God). These words complete the phrase ‘Exideret ne tibi divini muneris author’ (So that God should not pass out of thy thoughts), a quotation from Romans 1:20.62 The phrase reminds us that, for the purpose of making his presence known, the Creator stamped his image on every growing thing.

It has been suggested that the plants in Moreelse’s portrait are inventions of the artist’s imagination and that they indicate a scholarly interest in the burgeoning field of botany.63 This assumption is at least partially correct; the painter and/or his subject certainly had knowledge of botany. But far from being inventions of the artist’s fertile imagination, both plants appear in several early modern printed herbals. The euphorbia, a type of aloe belonging to the cactus family, was brought to Europe from the far-away lands of Africa and the Mediterranean (figs. 22 and 23). It is described as being shaped “like the fruit of Cucumber, but the ends or corners are sharper, and set about with many prickes.” Its roots are “very great, thicke, grosse and spreading,” and the leaves “long, ribbed, walled, and furrowed . . . sometimes exceeding a foot and a half in length.”64 Herbal texts agree that euphorbia was highly effective in producing heat, and note that its sticky sap “burneth or scaldeth.” Its extreme corrosiveness and capacity to raise blisters on the skin caused the plant to be rated hot in the fourth degree. Its natural heat was therefore very effective in alleviating the fatigue and apathy associated with an overabundance of cold humors. Ficino recommended rubbing the body with a poultice made of crushed euphorbia and oil as an effective measure against “dullness and forgetfulness among scholars.”65 His suggestion was echoed in succeeding herbals, which recommended rubbing such a mixture on the temples of “such as are very sleepie, and troubled with the lethargie.”66 Euphorbia’s ability to quicken the spirits had been valued since ancient times in the treatment of melancholia, where fits of heightened intellectual activity were followed by mopish sluggishness.67

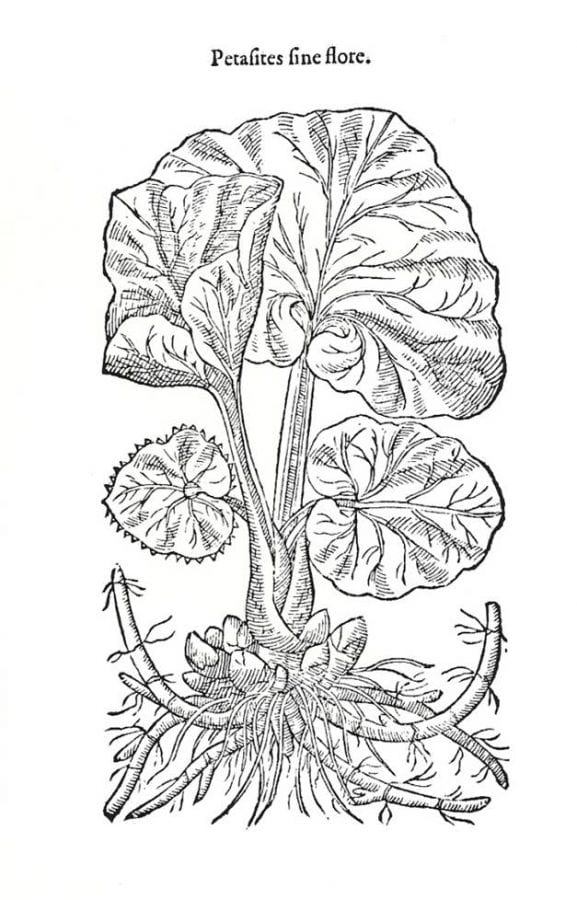

The second plant in Moreelse’s botanical duo, the broad-leafed butterbur (figs. 24 and 25) also appears in herbal sources exactly as Moreelse depicts it. Described as having “leaves very great like unto a round cap or hat,” large enough to “keep a mans head from raine,” butterbur grows in moist places and along the banks of rivers, lakes, and ponds. Despite its watery habitat, the plant was believed to be warm in quality , and highly effective against fevers because of its capacity to cool the body by instigating sweat.68 More importantly in the context of melancholia, butterbur was valued for its ability to lighten the spirits and drive evil thoughts from the heart.69 The euphorbia and butterbur in Moreelse’s portrait are a well chosen herbal pair. They complement each other both in their shared virtue of heat and in their common ability to address melancholia’s emotional lows. Butterbur mediated the fever of creative inspiration, while euphorbia tempered the frigid aftermath of humoral fires. Like the hot thistles and wet dock in Saint Jerome’s saturnine wilderness, euphorbia and butterbur conciliate the warmth and coldness of melancholia’s active and passive phases. Specifically, the two plants counter the effects of phlegm and black bile, both endemic among scholars.70

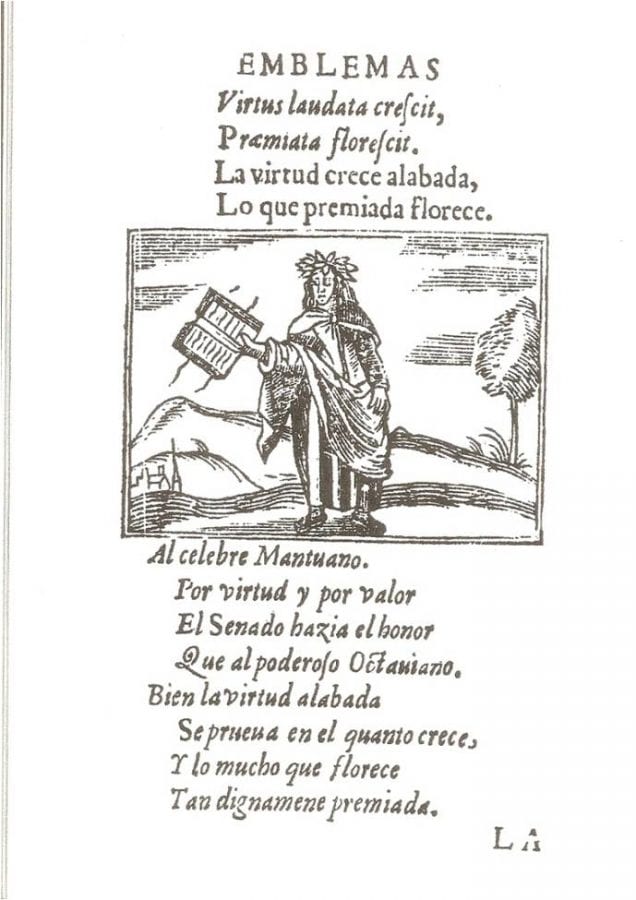

A prototype of Moreelse’s young academic appears in Hernando de Soto’s 1599 Emblemas moralizadas, accompanied by the Latin motto “Virtus laudata crescit, praemiata florescit” (Virtue grows glorified, that which is rewarded blossoms) (fig. 26).71 The emblem features the poet Virgil, clothed in a voluminous robe and crowned with laurel leaves, and displaying an open book in the manner of Moreelse’s scholar. The accompanying Spanish verse declares, “So virtue is glorified, proven by how much she grows, and how much she blossoms, so dignified [is] rewarded.” Viewed together with the emblem’s text and image, the plants displayed in Moreelse’s open book reinforce the motto’s message – like a growing plant, the rewards of integrity and hard work flourish when accompanied by recognition and praise. The carefully delineated herbs posit well-earned esteem and the promise of increased success, while the biblical maxim “Any herb shows the presence of God” recognizes the presence of God in all things and acknowledges the role of the Creator in the young scholar’s accomplishment. Like the fame of Moreelse’s newly-minted academic, the plants will thrive and multiply, even as their botanical character confirms his troubled membership in the distinguished brotherhood of Saturn.

Moreelse’s portrait continues the visual tradition, begun in the sixteenth century, of depicting scholarly hermits and saints. Like its predecessors, it communicates a curious combination of apprehension and reverence with regard to melancholia, the disease of intellect, and inspiration. In so doing, it makes reference not only to the look of humoral imbalance but also to its origins in antique philosophy and Christian morality. By the seventeenth century, artists had access to the imagery of melancholia as the product of an accessible and pervasive intellectual paradigm, which remained remarkably consistent throughout two thousand years of discourse. The curiously dichotomous nature of melancholia – which conferred joy and grief, pain and privilege, sin and virtue on its victims – exerted a powerful influence in the wake of Dürer’s emblematic Melencolia I. This attraction-revulsion was embedded in the fashionable secular topos of the misanthropic scholar and eventually that of the artist-creator, both privileged by intellect and inspiration, yet also blighted by Saturn’s influence.

The appearance of melancholia was achieved by calculated stylistic and iconographic choices, which drew from centuries of tradition. Artists such as Dürer, Rembrandt, and Moreelse made use of humoral theory to define an elite identity that did not depend on noble blood or material wealth but rather on talent, intellect, and virtue. They are but a few of the many artists who employed this strategy, seeking to appeal to an early modern audience, whose gaze was trained to discern the invisible internal self by external appearances. The examples treated here suggest that the concept of personality, as we now know it, was once tied to a visual and descriptive way of thinking, which associated the state of one’s inner soul inexorably with the outward appearance of the body. Ultimately, recognition of the artistic and socioscientific contexts inherent in the melancholic persona provides historical justification for certain ongoing cultural conventions common today, such as the stereotype of the absent-minded professor, the quirky, creative genius, and the conviction that unbridled materialism can instigate physical and mental maladjustment.