Although evidence shows that pre-primed canvases were used extensively during the seventeenth century, little is known about the purveyors of those supports. This paper offers a review of the currently known sources on professional primers, combined with technical analysis and archival and art market research to explore their role in the spread of colored grounds. A new method is proposed to establish the presence of a professional primer when no archival material is available, based on clusters identified in the Down to the Ground database of Netherlandish colored grounds. Using paintings and their grounds as primary sources illuminates how the relationship between artist and supplier contributed to the rapid spread of colored grounds, and how professional primers impacted local artistic practice.

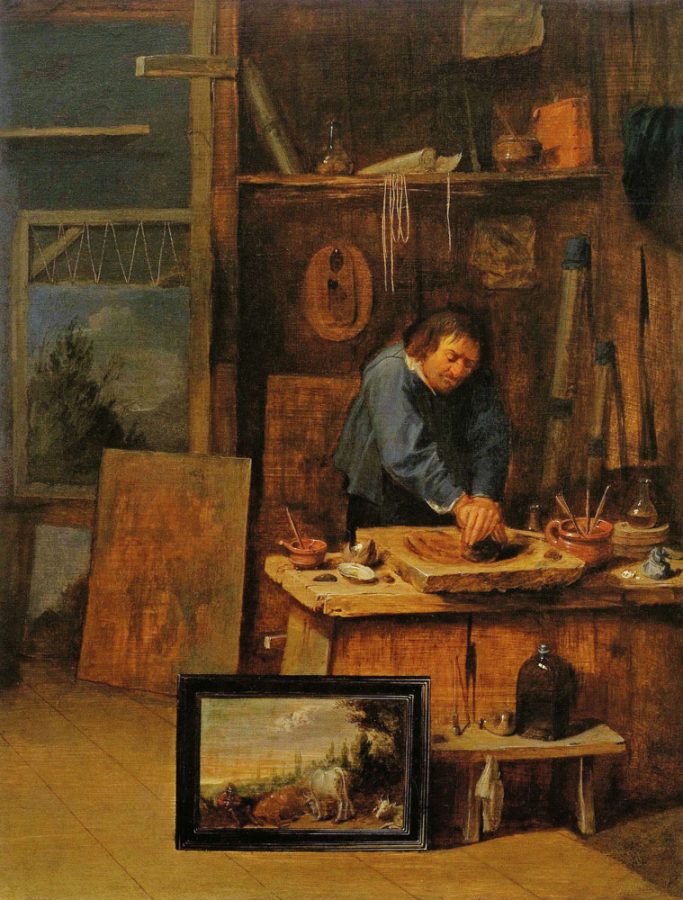

Where did seventeenth-century Netherlandish painters obtain their supports? Who was selling them, and what exactly did they offer? Archival records name a variety of specialists—witter (whitener), primuurder (primer), plamuurder (filler), paneelwitter (panel whitener), paneelmaker (panel maker), doekverkoper (canvas seller)—all designations for individuals involved in the preparation and sale of panel and canvas supports. Although professional primers have been mentioned in the literature, their industry as a whole, and their essential role in the spread of techniques such as colored grounds, has not yet been examined.1 During the seventeenth century the craft of priming supports became recognized by guilds as a profession.2 Commercial primers provided panels and canvases to artists, and the fruits of their labor can be seen in the stacks of prepared supports depicted in artists’ studios (fig. 1), in surviving archival records, and in the ground layers themselves. While scant documentation has relegated these artisans to the background of art history, this paper will show that professional primers influenced artmaking through the materials they selected, the methods they employed, and the standards they set, all of which left a visible mark on artists’ supports and working practices.

Perhaps because of the limited archival evidence available, few have researched professional primers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries outside of artist-related case studies. The most comprehensive overview was written by Maartje Stols-Witlox in her 2017 book A Perfect Ground.3 She cites most of the previous studies and adds evidence of professional primers mentioned in historical recipe books. However, her section on professional primers spans four centuries; the focus of her work on recipes means that her discussion of the profession is brief; and many of her examples are from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Nico van Hout also includes a section on professional primers in his 1998 paper “Meaning and Development of the Ground Layer in Seventeenth Century Painting,” which, although also brief, gives numerous examples of professional seventeenth-century primers mentioned in guild records.4 Jørgen Wadum wrote about ready-made grounds and professional primers in his 1998 overview of panel-making techniques, but his comments are limited to Antwerp panel paintings.5 This paper combines such previous studies with new insights from the Down to the Ground (DttG) database of colored grounds in Netherlandish painting 1500–1650 to survey what is currently known about professional primers and propose a new methodology for identifying these individuals outside of the archive.6

Beyond acknowledging the existence of primers and highlighting their essential role in the artmaking process, this paper points out why it is important to gather as much information as possible about these actors as a means to properly interpret and contextualize technical and art-historical data from this period. To understand the artistic process, it is essential to identify who was responsible for which parts of the painting. This parsing of authorship and intent has been applied to studio assistants and other artistic collaborators, but not yet to suppliers and professional primers.7 This article aims to lay the groundwork for future research by assessing our current understanding of these crucial figures and proposing a way forward that combines archival and technical analysis.

Evidence of Professional Primers

Most of the evidence we have for professional primers comes from archival records such as guild registers and ordinances, contracts, and petitions. We also have circumstantial evidence of their work, such as the presence of many primed canvases in artist and dealer inventories.

Archival Evidence

Guild registers (liggeren) reveal that numerous professional primers were active in Antwerp in the early seventeenth century.8 In 1604, Philips de Bout (d. 1625) was the first to hold the title of witter (primer; whitener) and lijstmaker (frame maker) in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke.9 When Philips’s son Melchior (act. 1625/26–1658) took over from him in 1625 or 1626, he too was referred to as a witter and peenelmaecker (panel maker), while his father was then only listed as a witter, perhaps reflecting their changing roles in the studio.10 Another De Bout family member, Frederick, was also a witter, and the witter Adriaen van Lokeren worked on the same street as Philips and Melchior.11 Bastiaen Jacques (act. ca. 1620), paneelwitter (panel primer), became a free master in the Guild of St. Luke in 1620–1621, and Hans van Hove (act. ca. 1625) was listed as a witter in 1625–1626.12

A witter prepared panels with chalk and glue grounds by applying multiple layers and sanding them in between to achieve an extremely smooth surface on which to paint.13 From the liggeren, it appears that panel making and priming were often combined professions and that witters worked in the same studio as panel makers. Antwerp’s panel maker regulations from 1617 state that panels needed to be inspected before witting (priming). This regulation seems to confirm that priming took place in the panel maker’s studio, probably to prevent any defective supports from being covered with a ground before proper inspection.14 Little is known about these witters beyond their names and profession, but the presence of so many in Antwerp around this time suggests that there was enough work in the early seventeenth century to support multiple primers in a single city.15 Antwerp primers also prepared canvases as well as panels. In 1654, Antwerp doeckprimuurder (canvas primer) Peeter van Nesten (b. ca. 1609) testified that he had been visiting the home of painter Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert (1613–1644) to prime canvases for the past two decades.16 He likely offered this service to other artists in the city as well.

Although there are only scant archival references to professional primers in the Northern Netherlands, it seems likely that the surviving picture is incomplete. The first known acknowledgment of priming as a distinct occupation in this region appears in a 1631 guild ordinance from the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, where primuurders (primers) are listed alongside painters, gilders, upholsterers, and other artistic practitioners under the guild’s protection.17 This explicit inclusion suggests some degree of professional recognition, though it remains unclear how widespread or independent the occupation truly was. A later documented case is the 1647 contract to prime the Oranjezaal (Orange Hall) paintings given to the Haarlem-based primer François Oliviers (1617–1690), discussed below.18 In 1676, frame maker Leendert van Nes (act. 1676) submitted a petition in Leiden for permission to make and sell primed canvases and panels in the town, stating that since the death of his predecessor Dirck de Lorm (ca. 1635–ca. 1673), local painters had been compelled to purchase their supports elsewhere “to their great trouble and expense.”19 This complaint highlights the practical importance of having a local supplier of primed supports. Such evidence points to the regular use of pre-primed panels and canvases by the mid-seventeenth century and suggests that professional primers may have been more common than the surviving archival record indicates. However, it remains uncertain whether priming was consistently carried out by independent specialists or more often by the makers of the supports themselves. The distinction between panel and canvas preparation is also important: it is more likely that independent primers focused on canvases, whereas panels were typically primed in the panel maker’s workshop.20

Suppliers of primed supports could also have been art and materials dealers. Antwerp panel maker and art dealer Hans van Haecht (ca. 1557–1621) had two large geplemuerde (primed) canvases and more than 170 geprimuert (primed) panels of various sizes in his shop.21 In Rotterdam, the 1648 inventory of verfhandelaar (color merchant) Crijn Hendricx Volmarijn (ca. 1601–1645) and his wife, Tryntge Pieters Hollaer (d. 1646), listed more than two hundred bereijt (prepared) panels and canvases of various sizes.22 Recently, Marleen Puyenbroeck has discovered that the Rotterdam paint store long associated with Abraham Lambertsz Bubbeson (1619/1621–1671) was actually owned and managed by his wife, Ermptgen van Putten (1614–before 1680).23 The 1673 shop inventory lists a number of available supports, including large rolls of geplamuert doeck (primed canvas), further described in the following section.24 Van Putten’s shop was inventoried again in 1680, when her third husband, Jacob Abrahamsz van Koperen (ca. 1622–1682), sold the business on her death.25 The inventories of the Rotterdam shops show that they also sold materials that would likely have been used for priming supports, such as large quantities of chalk, earth pigments, and lead white.26 In 1643, Leender Hendricx Volmarijn (ca. 1612–1656) petitioned to open a shop for artist’s materials, including “all kinds of prepared and unprepared paints, panels, canvases, brushes, and all other tools useful to the art of painting” in Leiden.27 And Johannes Gerritz Croon (1630–1664) and Pieter Heeremans (act. 1675), among others, ran shops selling supplies and painting supports in Amsterdam.28 Additionally, under a recipe for priming canvases, author Simon Eikelenberg (1679–1704) writes that one can purchase geplumeerde doecken en pennelen (primed canvases and panels) on the Haarlemerdijk in Amsterdam.29

Only a handful of primers and vendors of prepared supports can be identified by name in the archival record. On its own, this limited evidence would suggest that the trade in pre-primed canvases was marginal, yet other kinds of sources point in the opposite direction. Inventories list primed canvases, and contemporary texts describe them as if they were readily available, creating the impression that pre-primed supports were in fact common. Without further archival material, we must look to the paintings themselves for further evidence of professional primers, considering the demand for this service and the many reasons a painter might outsource this task.

Technical Evidence

Van Hout calls priming a “slow and dirty job” that, he argues, artists would want to outsource to professional primers.30 Preparing panels with layers of chalk and glue was a labor-intensive task. For canvas, the process of applying the first ground was less laborious than for panel, but it was still arduous and time-consuming, especially for large formats. The canvas had to be stretched onto a strainer, sized with glue, and then primed with ground layers, which would often have been applied with a special knife.31

Evidence for the existence of professional primers is not confined to archival sources. The recurrence of specific ground layers with similar compositions among multiple artists in one area suggests the involvement of a professional primer, a point that will be developed later in this article. The stark differences in grounds used by the same artist in different locations, indicating locally purchased supports, is another piece of evidence. We can also see from the supports themselves, canvases in particular, certain details such as the lack of cusping (the scallop-shaped impressions left by the canvas’s original stretching), or the ground extending all the way to the edge of the canvas, which indicate that the canvas was cut from a larger piece.32 For a professional primer, it would have made economic and practical sense to prepare sizeable swaths of canvas and to cut pieces from them as needed. The inventory of a Rotterdam painters’ supply shop owned by Ermptgen van Putten (1614–before 1680) lists several rolls of primed canvas measuring from between nine ells in length and two ells in width (approximately 6.3 x 1.4 meters) to ten ells in length and 1.75 ells in width (approximately 7 x 1.05 meters).33 Xenia Henny writes that these rolls of canvas were presumably imported from Antwerp and that the size of the rolls indicates small-scale mass production of primed canvases in the seventeenth century.34 We can assume that artists preparing their own canvases would not prepare a roll like this but would instead prime only a few stretched canvases at a time, saving time and space for painting. We know from inventories that painters often had a number of unpainted, primed canvases sitting in their studio, indicating that they either bought or primed a few individual canvases at once.35 Abraham Bredius’s Künstlerinventare includes numerous mentions of primed supports among artists’ possessions: eleven primed panels and three primed canvases owned by Utrecht painter Jacob Marrell (1613–1681), for instance, and eleven bereyde (prepared) panels with grounds and a large gegrondverwt (grounded/primed) canvas among the possessions of Barent Theunisz Drent (1577–1629).36 With so many prepared supports, space became a concern, especially for larger primed canvases, which needed time to age before use. Having many of these sitting in the studio for months would have been inconvenient for painters.37

One could also speculate that the large numbers of standard-size canvases and panels also signal the presence of professional primers. Because these supports were produced in regular dimensions, primers could prepare many at once in bulk, keeping a stock ready for sale to artists and dealers. This not only ensured a steady supply but also allowed primers to plan and economize their use of materials more deliberately.38 Another clue that a professional primer was responsible for a support lies in the skill with which it was prepared. Although the specific maker of a primed panel or canvas is nearly impossible to identify without accompanying documentation, the skills of these individuals played an essential role in both the appearance and preservation of the primed supports they made, as will be discussed below in relation to the primer of the Oranjezaal. The priming of a support was a craft that required considerable artistry in its own right.

The Impact of Primers on Studio Practice

In the sixteenth century, artist’s studios were mostly responsible for the preparation of their painting supports. It is unclear exactly when the transition to pre-primed supports took place. In 1668, the anonymous British author of The Excellency of the Pen and Pencil implies that the practice was already quite standard: “I could teach you how to prime it [the canvas], but it is moiling work, and besides, it may be bought ready primed cheaper and better than you can do it your self. Few painters (though all can do it) prime it themselves, but buy it ready done.”39 To what extent this was true in the seventeenth-century Netherlands is uncertain, and it is highly likely that many painters continued to prime their own supports. Nevertheless, generalized comments like this suggest that there were abundant commercial options for prepared supports by the seventeenth century.

The (Proposed) Relationship Between Painters and Primers

For panel paintings, we have clear evidence that professionals applied at least the first chalk ground, but it remains unclear who was generally responsible for applying the second ground layer. Second grounds were common in Dutch painting and appeared in more than two-thirds of the panels and canvases studied for the Down to the Ground project. Their function varied: on panel they were needed to isolate the absorbent first chalk ground from subsequent oil-based paint layers, while on canvas their function must have been largely coloristic, as they were often applied over oil-based first grounds. Second grounds on panel were often lightly colored in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, but it seems likely, based on the variation in pigments found in these layers, that the guild ordinances concerning witting only applied to the first ground of chalk and glue and that painters applied the second ground in their studios. We have proof that this was the case for a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century type of translucent, peach-colored ground called the primuersel, which was applied over the underdrawing, indicating that it must have been done in the studio.40 When lead white-based second grounds came into use, both white and colored, their opacity meant that the underdrawing had to be applied on top of the ground. This practice makes it harder to ascertain whether or not the second ground was applied in the studio.

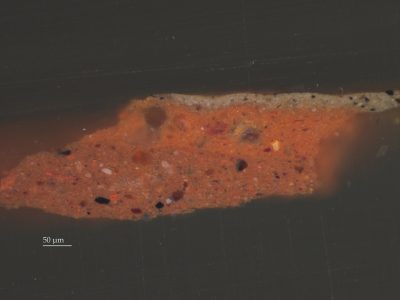

In both panel and canvas paintings, the presence of unusual pigment mixtures including ultramarine, verdigris, and red lake in some ground layers suggests that these layers, at least, were applied in the artist’s studio. These pigments were expensive and unlikely to be used by a professional primer in the layers of a ground. Their presence instead points to materials repurposed directly from the painting process. Painters often stored their brushes in a kladpot or pinceliere, a container of oil that could accumulate pigment residues over time. Such a vessel appears in David Ryckaert III’s (1612–1661) Paint Making in a Painter’s Studio: a terracotta pot to the right of the grinding tablet holds several brushes (fig. 2). The presence of this container, along with a clear bottle of plain oil, suggests that both mediums are being used to prepare the brown paint depicted. The pigmented oil from the kladpot, a unique byproduct of the painting process, was sometimes reused as a drying agent in grounds.41 There are historical recipes for this kind of reuse, but it can be difficult to detect in completed paintings.42 The small quantities and dispersed distribution of pigments make them easy to overlook, especially in the lower layers where such materials would normally not appear. One known example is the lower ground of Hendrick ter Brugghen’s (1588–1629) The Incredulity of Thomas (ca. 1622) (fig. 3) at the Rijksmuseum. Here, a particle of copper blue is present in the first red ground layer (fig. 4), suggesting that this layer was applied in Ter Brugghen’s studio, probably from a kladpot.43 This painting is also unusual in its ground layer colors. A second red ground layer overlays the first, lending a warm tone to the entire composition. Ter Brugghen’s paintings typically feature a light brown or gray second ground; this double red layering appears to be unique within his surviving oeuvre.44 The presence of two red grounds and the use of pigment residues in the first ground suggest that The Incredulity may have been an experimental work, created outside the artist’s typical working process, which may have involved pre-primed canvases.

Thus far, no seventeenth-century source has been found to document the purchase and subsequent alteration of supports by artists.45 While the initial chalk and glue priming of panels is relatively well documented, as discussed above, the responsibility for the application of the first ground on canvas remains ambiguous. Discerning who applied subsequent ground layers is further complicated on canvas, since the layers are usually all oil-based and consist of a range of pigments. The evidence for painters altering purchased supports is circumstantial but credible.46 Drawings between the first and second ground layers are one argument in favor of such a practice, and the variations of the second ground layer’s color, composition, and thickness on a similar first ground layer are another. This is exemplified in the work of Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), who used a range of ground types throughout his career, with varying second grounds in particular.47

The Need for Professional Primers—Oliviers and the Oranjezaal

One of the best sources we have, and in fact the only one that connects a professional primer to a known artwork (or in this case artworks), is the contract to decorate the Oranjezaal, a ballroom in the Royal Palace Huis ten Bosch in The Hague.48 In December 1647, the Haarlem-based primer François Oliviers (1617–1690) received the contract from the stadholder’s secretary, Constantijn Huygens, to prepare and deliver thirty canvases by May 1, 1648, for the impressive price of 1200 guilders.49 The average payment of 40 guilders per canvas was a high cost compared to standard canvas and painting prices of the period, though contemporaneous inventories lack direct evidence for the retail cost of primed canvases.50 The Oranjezaal works were exceptional in size and must have required custom stretchers that took more time than usual to create, which further complicates cost comparisons. It remains unclear whether Oliviers earned more for the Oranjezaal than he did for other priming jobs, but his selection for this princely commission does point to a certain level of trust or status.

The thirty primed canvases were sent to the twelve painters tasked with the decoration of the Oranjezaal, their common source ensuring that each painting was the right size and that all shared the same high-quality ground. The color of this ground is a light beige, chosen to match the wooden paneling of the hall to achieve greater visual unity.51 The canvases all received a glue size layer, followed by an oil ground of lead white with a little umber, applied in one or two layers. Some of the paintings have small amounts of black, red earth, or yellow ocher and chalk, which indicates the use of several batches of ground paint.52 Aside from supporting a goal of aesthetic cohesion, this light beige ground has ensured an extremely high level of preservation of all of the Oranjezaal paintings.53 This speaks to the benefits of hiring a skilled primer for such an important project. Oliviers applied the ground quite thinly and smoothed it into the weave of the canvases so that they would remain flexible and could be rolled without cracking.54 In a recently rediscovered letter, Oliviers wrote to Huygens in 1649 that he was sending four rolled canvases that could be sent on to the artists “without concern,” since they were “very well taken care of.”55 This phrasing could be interpreted as Oliviers expressing pride in his work, or it could simply mean that he thought the canvases were packed well for transport. In either case, he expresses confidence in the quality of the supports that he is sending. His skill as a primer is validated by the single canvas in the Oranjezaal that he did not prime. Lord of the Seas, one of two works by Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert (1613–1654), is painted on a much thicker and darker double ground on a different canvas, due to a last-minute change in painters.56 Unfortunately, this ground has had a negative effect on the painting’s condition, causing structural deformations, saponification (the formation of lead soap protrusions), and darkening of the ground, which no other painting in the Oranjezaal displays to this extent.57

The choice of Jacob van Campen (1596–1657), the artistic director of the project, to distribute prepared canvases from a skilled professional primer to the many venerable yet disparate artists hired for this commission, speaks to the importance of the ground’s color and application.58 Van Campen and Oliviers were both also from Haarlem, which indicates the importance of networks and local contacts for professional primers.59 This example reveals a great deal about how and why professional primers were chosen for commissions and about the skill involved the craft of priming. A painting’s longevity depended on the quality of its ground, a fact that was well known and discussed in the seventeenth century.60

Cost of Materials, Material Properties

Longevity was not the only thing on painters and primers’ minds; they also had businesses to run. By entrusting the task of priming to professionals, painters lost some control over the materials and methods used. While the choice to outsource priming saved both time and money, it did not necessarily lead to a drop in quality. By priming panels and canvases on a larger scale, professional primers could buy materials in bulk and keep costs low by offering standard sizes with popular grounds. The chance to cut costs would certainly have been as attractive to professional primers as it was to painters in the seventeenth century; as the market for paintings flourished, it was beneficial for painters to find new techniques and materials that would raise productivity and lower costs as they competed on the crowded market.61 The pioneering work of John Michael Montias, who applied concepts from economic history to the study of Dutch art, was the first to label these impulses as process and product innovations in the art market.62 One of the techniques that many painters gravitated toward was the use of a colored ground, which allowed them to paint more quickly and efficiently by leaving it exposed, often as a midtone. The pigments used for colored grounds were considerably less expensive than the popularly used lead white.63 Colored grounds could thus be termed a process innovation for their ability to speed the painting process and lower the cost of materials.64

Professional primers would also have been affected by market factors. Success in business would likely have been achieved through a combination of networking and reputation development; the choice of the best available materials for the lowest price, to increase their profit margins; and a combination of collaborating with and observing artists in order to offer the most desirable grounds. The Oliviers example shows that, although commissions like the Oranjezaal did not come along often, a well-connected and skillful professional primer could make quite a respectable income. Unfortunately, our lack of data on this industry means that much of this is speculation, but perhaps in the future it will be possible to connect more primers with their work and thus gain deeper insight into their processes

Beyond the Archives: Cluster-Based Evidence

![Map of known (red) and proposed (orange) cities with professional primers. Author map based on John Lodge [I] and John Lodge [II], The Seven Provinces of the Netherlands, ca. 1780, hand-colored engraving, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Fig5_Hall-Aquitania_RP-P-AO-1-64_Rijksmuseum-400x344.jpg)

Proposed Cities and Clusters in the Literature

In the context of city and artist-related studies, Ella Hendriks, Karin Groen, and Liesbeth Abraham have explored the presence of professional primers in Haarlem.67 Until recently, no names of Haarlem primers were known, but the 1649 letter discussed above has located Oliviers in Haarlem, and from there Lidwien Speleers and Michiel Franken were able to find him in the archives.68 Although Oliviers is the only primer identified in Haarlem so far, Groen and Hendriks suggest that Frans Hals (1582–1666) must have purchased his canvases and panels from a professional primer who was likely active before 1631, when the profession was recognized by the guild.69 They conclude this based on the fact that, among Hals’s paintings, even those that are close together in date have grounds of varying compositions on many different grades of canvas, indicating that Hals purchased supports from a supplier as needed.70 Hals used both light pink and ocher grounds for the warm midtones around cuffs and collars, as seen in his Portrait of Duijfje van Gerwen (1618–1658), where the exposed pinkish beige ground captures the translucence of her white collar (fig. 6).71 This “flesh-colored” ground seems to have been particular to Haarlem. Groen and Hendriks suggest that it is connected to the previous generation’s light pink primuersel on chalk-grounded panels: “Haarlem primuurders seem to have continued this application of a flesh-colored priming when canvas supports became the vogue. The introduction of painting on canvas does not seem to have coincided with the import from Italy of recipes for priming them, at least not in Haarlem.”72

Sabrina Meloni and Marya Albrecht have done extensive research on the work of Jan Steen (1626–1679), with a focus on his mobility between cities and possible use of local materials and suppliers.73 Based on principal component analysis of his grounds, they suggest The Hague as a particularly likely place for Steen to have purchased professionally primed supports.74 Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) also varied his grounds as he traveled. Based on their analysis of his paintings in the National Gallery London, Jo Kirby and Ashok Roy concluded that “Van Dyck seems to have been content to use the priming method in common currency in the country in which he was painting, and perhaps this indicates also the habitual use of ready-primed canvases from local sources of supply.”75 The materials of Van Dyck’s grounds produced in Rome show strong similarities to those of other artists active in the city around the same time, and the grounds of paintings he made in Brussels and London were also distinct.76 This pattern of using different grounds dependent on location has been observed in the work of other itinerant artists and presents further circumstantial evidence of professional primers working in these cities.77

New Clusters Based on the Down to the Ground Database

The preceding sections have illustrated the gap between available archival records and the practical evidence that there were far more professional primers at work than those records show. In order to properly understand and contextualize phenomena such as the introduction and spread of colored grounds in the Netherlands, it is vital to construct as complete a picture as possible of the actors involved. The primed paintings themselves can help to identify the presence of a professional primer around a certain time in a particular city. The DttG database has allowed this type of identification for the first time by collecting as much data about colored grounds as possible and analyzing it to identify clusters and patterns. A cluster of multiple artists using the same ground type in one location suggests that their primed supports could have been supplied by a single individual. This research is still in its early phases, but two examples of how these clusters might look are outlined below.

Utrecht

Data on a large group of paintings by the Utrecht Caravaggisti and their peers has shown very similar ground layers in many of these works. Chiefly in the lower layer, we see two types, both based on red earth. Type 1 has a bright orange color under the microscope due to the overwhelming presence of red lead and does not appear to have any other pigments present. This type can be seen in the first ground layer of Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Concert (ca. 1626; fig. 7), which is composed of red earth with some aluminosilicates and quartz (fig. 8).78 Type 2 is a more muted red color with particles of carbon black, lead white, earth pigments like umber, and dark red particles of red iron oxide. The first ground layer of Gerard van Honthorst’s (1592–1656) Old Woman (1623; fig. 9) is of this type, composed of red earth and aluminosilicates with darker particles of umber and red iron oxide (fig. 10).79 Wayne Franits has termed the period of about 1620–1624—in which Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerard van Honthorst, and Dirck van Baburen (ca. 1592/93–1624) had all returned from Italy and were living near one another and working on similar subjects—“the Utrecht laboratory.”80 This period of quotation, competition, and productivity would have been the perfect entrepreneurial environment for a professional primer. The popularity of work by the Utrecht Caravaggisti, particularly their genre portraits of musicians and merry drinkers, created a consistent demand for primed canvases in standard sizes, with ground colors all intended to have similar visual effects. The presence of a professional primer in Utrecht makes even more sense when looking at the grounds of Abraham Bloemaert, who taught two of the Utrecht Caravaggisti. Both types of red earth ground appear in his work of this period as well as the decade preceding it. One example is Joseph and His Brothers from 1600 (fig. 11), which has a thin, light gray second ground over an orange Type 1 first ground (fig. 12).81

One of the most surprising discoveries about the Utrecht Caravaggisti is that, despite their famous travels to Italy, when they returned home they all tended to use a very “Netherlandish” double ground of light brown or gray over red earth, rather than experimenting with the dark single grounds used by Caravaggio (1571–1610) and his Roman contemporaries.82 One explanation is that they simply followed the habits of their teacher Bloemaert; another, although we have no documentary evidence for this, is that they used the grounds applied by a local primer in Utrecht. It is likely that the gray or brown over red ground was first introduced to Utrecht in the 1590s by Bloemaert, and that, by the 1620s, it was being regularly produced by a primer supplying him and his circle with canvases.83 Tellingly, Van Honthorst used a completely different ground when he worked in Italy—a single, dark brown layer containing a multitude of variously sized red, yellow, and black pigments.84 Van Honthorst was also one of the painters of the Oranjezaal, so we know that for those six paintings he worked on Oliviers’s light beige ground. It seems as though he shifted toward using similarly light grounds in his later paintings, and in general he was flexible in his use of ground colors throughout his career.85 One example from his time working at the court in The Hague, his Double Portrait of Frederik Hendrik (1584–1647) and Amalia of Solms-Braunfels (1602–1675), is painted on a double ground with a thick yellow ocher second ground, which has not yet been found in any Utrecht paintings.86 It is likely that Van Honthorst used grounds that were locally available to him, rather than applying the same ground wherever he traveled, a tendency also discussed by Elmer Kolfin in his contribution to this issue of JHNA. The preceding section shows that more painters used the local priming colors over the ones they were accustomed to, which strongly indicates that they preferred to buy pre-primed canvases. This again suggests the presence of a local primer in Utrecht.

Antwerp and Further Clusters

Research and conservation reports at the KIK-IRPA in Brussels have tentatively identified another cluster: a small group of light gray second grounds over chalk first grounds in panel paintings from Antwerp. This is quite a small sample, as Antwerp paintings are underrepresented in the DttG database, and no systematic cross-section analysis has been performed on this group, but the ground type has been identified in late sixteenth-century panel paintings by Maarten de Vos (1532–1603) (fig. 13), Michiel Coxcie (1499–1592), Frans Pourbus I (1545–1581) and Frans Francken I (1542–1616).87 Vermeylen’s research into the Antwerp color merchant Michiel Cock, active in 1580 and known to have supplied Maarten de Vos with materials, suggests that clusters of ground types could also be connected to known dealers.88 Groups such as this represent fertile ground for further research as the DttG database grows and more targeted technical analysis is possible. Cities for which promising archival evidence exists—such as Leiden after 1676, when Leendert van Nes petitioned for the right to supply primed supports; or Rotterdam, where inventories of artists’ materials shops have been preserved—may prove especially productive for future research connecting technical and documentary sources.

Conclusion: The Role of Primers in the Spread of Colored Grounds

Even with limited archival evidence, we can be sure that professional primers were working throughout the seventeenth-century Netherlands. Beyond their basic offering of prepared panels and canvases, it is likely that professional primers played a key role in the spread of colored grounds. Concerning the introduction and spread of this immensely popular and consequential painting technique, professional primers must have acted as scalers—those who expand an existing practice—rather than innovators. The demand came from the artists, who would have been the first to introduce this technique, but primers had a wider reach and a foundational impact on the artistic communities they supplied.89 Primers’ decision to offer supports prepared with colored grounds would have contributed to the popularization and spread of this technique. While knowledge transmission of motifs and techniques between artists has been well studied, primers, more than other suppliers, represent a missing link in the network of technical knowledge transfer, connecting artists who may not have been in contact with one another and playing a vital role in the creation of artworks by applying the crucial first layers of paintings. We know that some artists, like Willeboirts Bosschaert, had preferred primers, and it is likely that further relationships between artists and suppliers will be uncovered as more attention is devoted to this topic.

Professional primers and artists must have had a symbiotic relationship during this time, one that was more complex than simply producing and purchasing ready-made products. While some artists likely purchased what was inexpensive and readily available, others probably ordered their supports with instructions for what they wanted, as evidenced by the great variation in ground layers throughout the seventeenth century and the sources we have connecting professional primers to their clients. It is not likely that professional primers would have introduced completely new ground colors and materials independent of artistic demand, and we know that artists experimented with new ground colors in their studio. However, once a type was introduced, as illustrated by Abraham Bloemaert in Utrecht, primers could then reproduce the requests of innovative artists for their other customers. Furthermore, many artists altered the supports they bought, so the industry connected to prepared supports was a layered process of commission, purchase, and use. Technical research can help us move forward when archival sources have been exhausted, and as we grow our datasets, we may be able to find more clusters of grounds to indicate that a professional primer was at work. Once clusters are identified, it may be possible to return to particular archives with clear questions, as Speleers was able to do for Oliviers in Haarlem. By combining diverse sources, we can continue to learn more about professional primers and thus better interpret artistic innovation and knowledge transfer in the seventeenth-century.

![Map of known (red) and proposed (orange) cities with professional primers. Author map based on John Lodge [I] and John Lodge [II], The Seven Provinces of the Netherlands, ca. 1780, hand-colored engraving, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Fig5_Hall-Aquitania_RP-P-AO-1-64_Rijksmuseum-720x540.jpg)

![Map of known (red) and proposed (orange) cities with professional primers. Author map based on John Lodge [I] and John Lodge [II], The Seven Provinces of the Netherlands, ca. 1780, hand-colored engraving, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam](https://jhna.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Fig5_Hall-Aquitania_RP-P-AO-1-64_Rijksmuseum-112x84.jpg)