Contrary to what we thought we knew about the provenance of Paulus Potter’s iconic The Bull (1647; Mauritshuis, The Hague), the painting served as a gift to Prince William IV of Orange in 1749, after a stay of many decades within the family of Barbara Schas and Willem Fabricius in Haarlem. The painting may have been produced, or adapted, as a giant piece of decoration for a private house in The Hague.

Paulus Potter’s The Bull, long in the collection of the Royal Picture Gallery at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, has become one of the iconic images of seventeenth-century Dutch painting (fig. 1).1 Praised in the first catalogue of the collection of paintings owned by stadholder William V of Orange in 1770, it became one of the attractions of the French national museum in the former Louvre palace in Paris, after revolutionaries seized the princely collection in The Hague in 1795.2 In France, it was considered the epitome of Dutch realism, with its combination of humble subject matter and highly finished naturalism. Although the painting’s reputation suffered in the nineteenth century under the criticism of Eugène Fromentin and others, appreciation for the work of Paulus Potter in general, and this painting in particular, saw a remarkable comeback in the twentieth century. Despite his very short period of artistic production—born in 1625, the painter died in 1654—Potter is now viewed as one of the most important animal and landscape painters of the Dutch seventeenth century. He is highly praised for the tone, light and atmosphere in his works. The fairly recent observation that the anatomy of his famous Bull may be more of a composite than a completely true “portrait” of an existing animal has done little to diminish the painting’s popularity with the general public.3

Although the painting is fully signed and dated 1647 on the fence at the left side of the work, we know very little about the circumstances under which the Bull was created. Careful visual analysis of the painting and X-ray photography have brought to light that the original canvas of the painting must have been much smaller, and that it was enlarged by the painter himself on all four sides in order to reach its present size. Thus, it seems that Potter conceived the painting first as a mere picture of a bull. Later on in the production process, he must have changed his mind, or followed the wish of an unknown patron, in order to include the animal within a larger group of cattle, herded by a man, and to place it in a wider landscape, obviously somewhere between The Hague and the nearby village of Rijswijk, identifiable by the steeple of its church on the horizon.4 We do not know the reason why Potter expanded the painting, but given the adjustments to its size and the resulting enormous scale of the work (236 x 339 cm), it is hardly conceivable that it was produced for the free market. The painting’s definite form seems to suggest that it was meant to be included in some kind of interior decoration and had to fit a designated place. This is, however, merely conjecture, since very little is known about the work’s provenance, let alone its initial whereabouts. Nevertheless, some new information on the provenance is presented here.

Potter’s Bull: A Gift, in Expectation of a Return

The earliest known mention of the painting comes from the inventory of the goods of Willem Fabricius (1709–1749), a member of the Haarlem city council and an alderman who had died on May 21, 1749 (figs. 2 and 3). On August 12 of that year, the picture, described as “a capital piece of painting by Potter,” was found in the side room next to the entrance of Fabricius’s house on Jansstraat (now number 55) in Haarlem. The décor of valuable paintings suggests that this side room functioned as a place for social gatherings in the Fabricius townhouse.5 As the inventory stated, the paintings in this and other rooms in the house were to be sold publicly; an auction catalogue was compiled for this purpose by the Haarlem painter and auctioneer Frans Decker (1684–1751). The auction took place only one week later, on August 19, in the premises of the Prinsenhof, adiacent to the Haarlem town hall, under Decker’s guidance.6

Obviously, Potter’s Bull was meant to attract as many buyers to the 1749 auction as possible, since it was sold as the very first lot. The auction catalogue described the piece as “an Extra Large and Capital piece . . . by Paulus Potter 1647, being, in its fullness of detail, force, and naturalness, the most extraordinary piece known by this great master in this country.”7 The work was sold to the auctioneer, Frans Decker, at fl. 630, a considerable sum at the time and by far the highest price in this auction, followed by a landscape and a flower piece by Jan van Huysum, a painting by Johannes Lingelbach, some paintings by Adriaen van Ostade, and Rembrandt’s Abraham and Hagar, on which more will be said later in this article.8 In total, the sale of the fifty-seven paintings in this auction fetched a sum of fl. 6,319, while the library brought another fl. 3,879 to the estate.

The fact that Potter’s Bull is mentioned in a 1754 list of paintings belonging to Princess Anna of Hannover, the widow of Prince William IV of Orange—hanging in the stadholder’s quarters at the Binnenhof, The Hague—has always led to the reasonable supposition that the painting was acquired at the Fabricius sale by Decker on the prince’s behalf. Sophie Drossaers and Theodoor Scheurleer, in their invaluable listing of the inventories of the possessions of the House of Orange between 1567 and 1795, even speak of “the spectacular purchase” by the prince of Potter’s Bull.9 However, a manuscript annotation in a unique copy of the auction catalogue, kept in the archive of the Fabricius family, reveals that although the painting was, indeed, bought by Decker on commission, it was subsequently “given by the admiral Renst to the prince at his house te Loo.”10

There can be little doubt that this reference to “admiral Renst” concerns Jacob Reynst (1685–1756), who made his career as an officer in the Amsterdam admiralty. Jacob Reynst was the son of Pieter Reynst, the secretary and later a member of the Haarlem town council as well as an alderman, and Catharina Hasevelt. Since his older brother was destined for a political career, Jacob decided to pursue a career in the navy. By 1713 he was a captain in the service of the Amsterdam admiralty; in 1744 he joined the higher ranks to become rear admiral (schout-bij-nacht), and in 1748 and 1750 he profited from a substantial—even, in the eyes of some of his contemporaries, extreme and unnecessary—increase in the number of promotions by the prince, first to the position of vice-admiral and, in 1750, to lieutenant-admiral. Reynst did not need the money that came with these promotions: he descended from a wealthy family, and his marriage to Eva Clifford (1695–1764), daughter of a banker, in 1718 was also very succesful in financial terms.11 When taxed in 1742, his annual income was estimated at fl. 12.000, thirty to forty times the average income of a craftsman at the time. Reynst and his wife lived in a house on one of the best parts of Keizersgracht in Amsterdam, at the corner of Vijzelstraat, together with five servants; we also know that he owned a carriage and four horses, all of which testify to his affluent lifestyle.12

Jacob Reynst belonged to a group of naval officers who firmly supported the cause of Prince William.13 The princes of Orange had been barred from the stadholderate in most of the provinces of the Republic after the death of king-stadholder William III in 1702. William III’s nephew, Prince Willem Karel Hendrik Friso of Orange (1711–1751), who belonged to the Frisian branch of the family, became stadholder of Gelderland in 1722, of Groningen and Drenthe in 1729, and of Friesland in 1731. The wealthiest and most politically and economically important provinces of Holland, however—Zeeland and Utrecht—did not accept him until 1747, when fear of a French invasion of the Republic helped to catapult the prince into the position of admiral-general and captain-general in the service of the Republic, and as stadholder William IV in all seven provinces. The stadholderate was declared hereditary in 1749 as a prelude to the monarchical position the house of Orange would take after the Batavian-French interlude, from 1813 until the present day.14

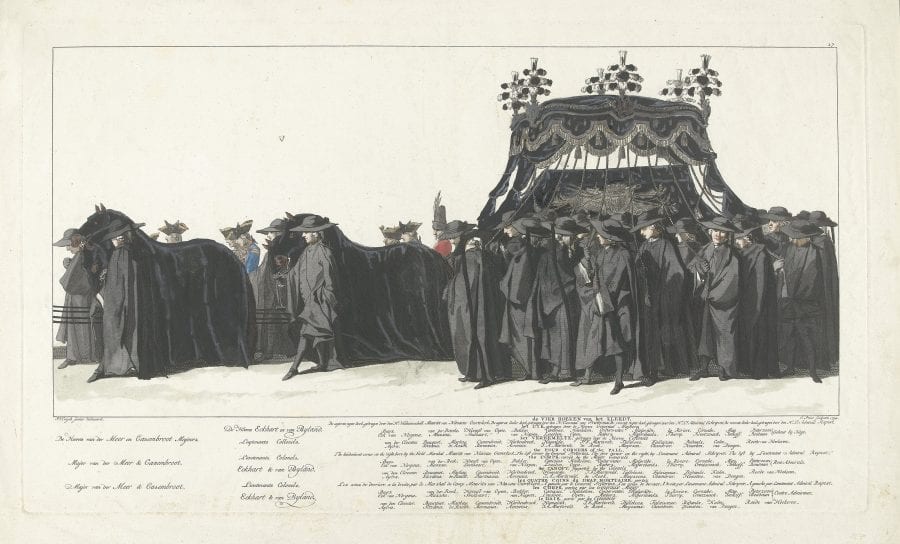

Thus, Jacob Reynst’s career as a naval officer paralleled William IV’s political and military career. Several letters in the Dutch Royal House Archives confirm the close relationship between the two men. Reynst presented Prince William with a horse (a “cornet”) in 1745, and the prince returned the gift by sending Reynst an even better Spanish horse with full gear. Reynst thanked the prince for this magnanimous gesture while excusing himself: it had never been his intention, he wrote, “to catch a big fish by throwing small bait.”15 Although this may have been true in the narrow sense of that particular exchange, it it clear that Jacob Reynst’s purchase of Potter’s Bull and his subsequent presentation of it to the prince in 1749 was only one step in a longer chain of exchanges of gifts and favors between the two, crowned by Reynst’s nomination to the highest position within the admiralty in 1750. The last thing Reynst could do in return, in 1751, was to accompany the prince’s dead body to his tomb in New Church, Delft, as one of the four principal pallbearers (fig. 4).

Apparently, Reynst had wished that the painting would be placed in the “huys te Loo.” This may refer to the palace, “het Loo,” near Apeldoorn, originally a hunting castle for the family of Orange (in Dutch, loo means “forest”), but redesigned and rebuilt on a grand scale under king-stadholder William III of Orange.16 It may well be that Reynst intended Potter’s Bull to join the other paintings that the young Prince William IV had gathered there in a gallery and a cabinet from 1733 onward.17 Many of those paintings were taken to The Hague in the 1760s and 1770s and were finally placed in the princely cabinet of paintings on the Buitenhof in 1774.18 Alternatively, Reynst may have meant the painting to be placed in one of the two smaller country houses that the stadholder had acquired in the vicinity of The Hague. In 1748, the prince—heedless of the risk of confusing later historians—had bought the estate of “de grote Loo,” also called “het huys te Loo,”19 and in 1749 the adiacent “kleine Loo,” next to the Huis ten Bosch palace. While the house on “de grote Loo” was reshaped by William IV’s architect Pieter de Swart into a playhouse, the grounds of “de kleine Loo” were transformed into the new seat of the princely menagerie, which was transported from “het Loo” near Apeldoorn to “de kleine Loo” near The Hague in 1749, the very same year that Jacob Reynst bought Potter’s Bull in Haarlem and presented it to the stadholder.20 There are, however, no indications that the painting was ever placed in either “het Loo” or in the “grote” or “kleine Loo.” The earliest mention that we have of Potter’s painting as part of the prince’s belongings dates from August 1754, when it could be found in one of the rooms of the princely quarters at the Binnenhof in The Hague, north of the former chapel. The painting is thought to have been taken there, together with other pictures, from the private rooms of the stadholder after his sudden death in 1751.21

Potter’s Bull as a Family Heirloom

While the above sheds new light on the trajectory of the Bull after its sale in 1749, the Fabricius family archives also contain valuable information on the painting’s earlier whereabouts and ownership. Willem Fabricius was not the original collector of most of the paintings that were sold at auction after his death in 1749. According to his parents’ will, his father Albert Fabricius (1676–1736), secretary of the Haarlem council, left all his paintings and his library to Willem in compensation for the jewelry given to Willem’s only sister, Helena Wilhelma (1703–1743), on her marriage to Willem Six (1692–1757) in 1723.22 By the time Willem was engaged to marry Wilhelma Henrietta Huyghens (1713–1747), in the fall of 1732, a prenuptial agreement again specified that all the books and paintings that belonged to his father were destined to come into Willem’s possession.23 Albert Fabricius made it clear that “Potter’s Bull had already been given to his son [Willem].” In Albert Fabricius’s final will of 1734, he revoked all stipulations in earlier testaments made by him or his late wife, with the explicit exception of his decision on the destination of his books and paintings.24

It may well be that Albert Fabricius had bought most of the pictures in his possession, either on his own account or in conjunction with his wife, Henriëtte Christine de Witt (1675–1724). This may have occurred around the time the couple bought and settled in their house on Jansstraat in 1704 (fig. 5).25 The house transferred to Willem upon his marriage in 1732,26 together with Potter’s Bull, and it was there, as we learned at the beginning of this article, that the painting was found in 1749.

A brief glance at the complete list of paintings that were sold in 1749 confirms that the collection had a distinctly local touch. There were six paintings by Adriaen van Ostade; four by Cornelis Pietersz Bega; three by Dirck Maes; two paintings each by Nicolaes Pietersz Berchem, Jan Steen, Jan van Hugtenburg, Cornelis Dusart, Richard Brakenburgh, and Jan van der Meer; and single pictures by Philips Wouwerman, Adriaen Brouwer, and Adriaen van de Velde. All of these painters had been active in Haarlem—some of them all their lives, others only at a certain stage of their careers. Lingelbach, Herman Saftleven, Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Gerrit Dou, David Teniers, and Jan Asselijn, also listed in the catalogue, do not seem to match this profile. Two paintings by van Huysum may have been bought by either Albert Fabricius or his son Willem, although no mention of such a purchase is found in Willem’s journal over the years 1737–44.27

Given the predominance of painters who were active in Haarlem in the second half of the seventeenth century, it may be that even Albert was not the original purchaser of these pictures, but that they were already in the possession of his family. We know from the will of Albert Fabricius’s mother that this is the case with at least three pictures, including Potter’s Bull. When Barbara Schas (1654–1725), widow of former burgomaster Willem Fabricius Sr. (1642–1708) (figs. 6 and 7) made her will on December 25, 1724, she bequeathed all her movable possessions in the country estate of Santhorst, between Leiden and The Hague, to her oldest son, Arent, who had already taken possession of the property. To her second son, Albert Fabricius, however, she left “the large piece of painting by Potter, a small piece by Rembrandt and a small [painting of a] papist church,” together with a damask tablecloth, eighteen napkins, and a towel, all already distributed to him, and 2,800 guilders in compensation for the marriage gift to his sister Barbara Cornelis.28 In an earlier version of her will, dated April 1, 1718, almost identical formulations are used, with the significant specification that the three paintings mentioned above were already in Albert’s house on Jansstraat at the time.29

We do not know how Willem Fabricius and Barbara Schas came to acquire these three paintings and what exactly caused Barbara Schas to leave them specifically to her son Albert in her wills of 1718 and 1724. If her intent was to leave him something of financial value, she could have easily extracted the corresponding amount of money from her estate, which had been valued at a dazzling fl. 300,000 at the death of her husband in 1708.30 Presumably, there was also some other value, perhaps a sentimental one, at stake in her decision to leave the three paintings to her son.

All three paintings can be found in the 1749 sales catalogue: Potter’s Bull (lot 1); “Abraham leading out Hagar, artfully and forcefully done, by Rembrand van Rhyn, 1 foot and 3 inches high, 1 foot and 9 1/2 inch wide” (lot 12, fl. 320); and “The interior of a roman catholic church, artful, by P. Neefs, 1 foot 2 inches high, 10 inches wide” (lot 33, fl. 61-10 to La Roy). The Rembrandt picture has understandably been connected to a painting with the same subject of exactly the same size in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, now attributed to Rembrandt’s workshop (fig. 8). However, since the painting sold in 1749 was already in the possession of the Fabricius family in 1718, the provenance of the work in the V&A must be revised.31 Pieter Neefs’s picture, with its unusual vertical fomat, may be a small panel of almost exactly the same size that is now in the Fondation Calvet, Avignon (fig. 9).32 But setting aside any ambiguities about the Rembrandt and Neefs, we can safely conclude that Potter’s Bull was already in Haarlem in 1718—in the possession of Barbara Schas, the widow of Willem Fabricius Sr., but placed in the house of their son Albert Fabricius on Jansstraat, where it remained until the auction of the paintings belonging to Willem Fabricius Jr. in 1749.

We do not know how Barbara Schas happened to acquire Potter’s Bull, Rembrandt’s Abraham and Hagar, and Neef’s church interior. We do know that she was interested in porcelain and other goods that were imported from the Dutch East Indies,33 so it may be that she played a role in the acquisition of these paintings as well. It is also possible that the three paintings by Neefs, Potter, and Rembrandt (and maybe others) had been bought by her late husband, Willem Fabricius Sr. Although there is no specific mention of paintings in their prenuptial contract from February 19, 1670, nor in their first will, from 1671, and a later one from 1698, this does not necessarily mean that there were no paintings in the household at the time. Besides, the wills state that the longest living member of the couple would inherit all their shared movable goods, with the exception of gold and silver coins, so Barbara Schas may very well have inherited the paintings from her husband at his death in 1708.34 Altogether, it seems likely that the paintings belonged to the common household of Willem Fabricius Sr. and Barbara Schas and may have already been in their house on Oude Gracht in Haarlem (fig. 10) before Willem Sr.’s death in 1708.35 From there, they must have been taken to Jansstraat sometime between 1704 (when their son Albert Fabricius bought that house) and 1718 (when Barbara Schas said the three paintings by Potter, Rembrandt, and Neefs were there).

Both Willem Fabricius and Barbara Schas also brought a number of high-quality portraits from their respective families into their common household, most of which have ended up, through the Fabricius family, in the possession of the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem.36 Among these are the pendant portraits of Willem Fabricius’s uncle Anthonie Charles de Liedekercke (1587–1661) and his wife, Willemina van Braeckel (1604/5–1670), by Johannes Verspronck, and their family portrait, together with their son Samuel (1638–1655), by Gerard ter Borch (fig. 11).37 These portraits had been left by Willemina van Braeckel to her sister Judith, Willem Fabricius Sr.’s mother. Through her grandmother Cornelia van der Meer (1610–1668) and her mother, Cornelia Nierop (1633–1679), Barbara Schas had probably also inherited the portraits of her maternal great-grandparents Nicolaes Woutersz (Van der Meer) (1575–1637) and Cornelia Claes Vooght (1578–after 1637) by Frans Hals, now also in the Frans Hals Museum.38 All these portraits, and more, probably hung first in the Fabricius household on the Oude Gracht, and later in the house on Jansstraat.39

The Earlier Provenance of the Bull: Room for Speculation

We do not know for whom the Bull was painted (or adapted), nor do we know how it came into the possession of Barbara Schas and Willem Fabricius. However, an early provenance from The Hague, where the Schas and Nierop families were firmly established, seems much more likely than one from Haarlem. Paulus Potter registered as a member of Saint Luke’s guild in Delft in August 1646, but there is no evidence that he ever produced a work of art in that town. Walsh suggests that the young painter may actually have lived with his parents in The Hague beginning in 1647, the same year his father, Pieter Sijmonsz Potter, registered with the guild there and in which Paulus Potter produced his Bull. In 1649, probably after his father gave up his membership in the Hague guild to leave for Amsterdam, Paulus Potter himself registered with Saint Luke’s guild in The Hague. In the spring of 1652, he followed his father to Amsterdam, where both his father and mother passed away half a year later, and where Paulus Potter himself died early in 1654.40

Could it be that the young Paulus Potter worked incidentally with, or for, his neighbor and father-in-law, the master carpenter and building contractor Claes Dircksz van Balckeneijnde (1599/1600–1664)?41 This may well have been the case for The Bear Hunt, a picture of a similar size as the Bull (their widths differ by only 1 cm) (fig. 12).42 Potter produced the Bear Hunt in 1649, the very same year in which Balckeneijnde’s new house and workplace on Dunne Bierkade (now no. 18) were completed.43 Potter’s widow, Ariaentgen van Balckeneijnde (1626–1690), acquired Dunne Bierkade 18 in 1667 from her father’s estate. The painting, in all probability, was in her possession at that time, and she subsequently kept it in her second husband’s house on Paviljoensgracht in the Hague as a memento of her late husband, together with his (probably posthumous) portrait by Bartholomeus van der Helst.44

For the Bull, painted two years earlier, we cannot establish such a possible connection to a Balckeneijnde property,45 except for one. The settlement of the division of the estate of Claes Dircksz van Balckeneijnde in 1667 took place on two occasions before Albert Nierop (1600–1676), lawyer in the Hof van Holland in The Hague (fig. 13).46 Interestingly, Albert Nierop was also the maternal grandfather of Barbara Schas, the first documented owner of Potter’s Bull. This may be purely coincidental, but it is at least theoretically possible that through these proceedings Nierop became aware of the existence and, possibly, the availability of the painting, and that he acquired it on this occasion. In that case, the painting would have descended to his daughter Cornelia Nierop (1633–1679) and subsequently to her daughter Barbara Schas, who brought it to Haarlem. But it is, of course, also perfectly possible that Nierop himself, or another of Barbara Schas’s forebears, had commissioned Potter to create the Bull for one of their dwellings.47

The Trajectory of a Bull

Now that we have come to the end of our journey back in time, uncovering some steps in the provenance of Paulus Potter’s Bull, we realize, once more, that a painting like this, even if we feel familiar with its appearance as a museum piece (as it has been ever since the late eighteenth century), must have represented different modalities of function, meaning, and emotional association in its various stages of its existence.

Potter’s Bull is, with all its baffling realism, nevertheless the work of a very young painter who had only recently registered as an independent master. As such, it must have made a smashing impression as a spectacular piece of decoration in a private house, whether in The Hague, in the immediate surroundings of the painter, or in the home of one of Barbara Schas’s ancestors.

Next, it demonstrably served as an heirloom, together with paintings by Rembrandt and Neefs, with a special status within the respectable Schas and Fabricius families in The Hague and Haarlem. This tallies with a more general pattern of the bourgeois memory cult within the Dutch Republic, in which certain paintings were assigned to specific heirs by testamentary decisions, usually not so much for the sake of money as of personal memory.48 Apparently, Potter’s Bull was such a painting.

The purchase of the painting by Jacob Reynst in 1749, and his subsequent gifting of the piece to the stadholder—probably in return for the favors that had been bestowed upon him by William IV in the preceding years—marks a transition in the function of this painting. Recently, scholars have demonstrated renewed interest in the phenomenon of gift giving and exchange as part of wider issues of allegiance and networking in the early modern period. We know that paintings incidentally functioned in this context, a practice that may look trivial from a modern perspective but must have enjoyed important meaning at the time.49 It was only because of the early death of the stadholder in 1751, and the following plans by his widow, Anna of Hannover, and his son Prince Willem V to arrange a public picture cabinet in The Hague, that this association of Potter’s Bull with gift giving and family memory was lost rapidly. At that point, Potter’s Bull became available for public viewing, allowing it to gain the national—indeed, international—renown it has enjoyed to the present day.