The Dutch art theorists Junius and van Hoogstraten describe the sublime, much more explicitly and insistently than in Longinus’s text, as the power of images to petrify the viewer and to stay fixed in their memory. This effect can be related to Longinus’s distinction between poetry and prose. Prose employs the strategy of enargeia; poetry that of ekplexis, or shattering the listener or reader. This essay traces the notion of ekplexis in Greek rhetoric, particularly in Hermogenes, and shows the connections in etymology, myth, and pictorial traditions, between the petrifying powers of art and the myth of Medusa.

Introduction

In his autobiography the Dutch poet, civil servant, and patron of the arts Constantijn Huygens recalls viewing a Medusa’s head painted by Peter Paul Rubens in 1617–18 in an Amsterdam collection (fig. 1). It left him confounded in that typical mixture of fear, desire, fascination, and horror we now call the sublime:

It is as if of Rubens’ many paintings, one always appears before my mind’s eye . . . It represents the severed head of Medusa, encircled by snakes that appear from her hair. In this painting he has composed the sight of a marvellously beautiful woman, who is still attractive but also causes horror because death has just arrived and evil snakes hang around her temples, with such inexpressible deliberation, that the viewer is suddenly caught by terror—since usually it is covered by a curtain—but that the viewer at the same time, and inspite of the horror of the representation, enjoys the painting, because it is lively and beautiful.1

Ambivalence is indeed one of the defining characteristics of the sublime. Sublime speech, according to Longinus, inspires wonder and transports the public out of themselves. “A well-timed flash of sublimity,” he adds, “shatters everything like a bolt of lightning.” The sublime inspires both fear and admiration, wonder and amazement, the apprehension of the terrible and the appreciation of beauty. But its effects also endure. The images conjured up by means of the phantasia of the orator are difficult to resist; they enter into the memory of the listener to stay there and cannot be shaken off.2 As the Dutch philologist and art theorist Franciscus Junius (1589–1677) put it, “That is great indeed . . . which doth still returne into our thoughts, which we can hardly or rather not at all put out of our minde, but the memorie of it sticketh close in us and will not be rubbed out.” Junius also describes how viewers become tongue-tied and transfixed by the sight of art: “great rings of amazed spectators together are led into an astonished extasie, their sense of seeing bereaving them of all other senses; which by a secret veneration maketh them stand tong-tyed.”3

This phenomenon would be repeated in almost identical terms by Rembrandt’s pupil Samuel van Hoogstraten in his Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst: “[T]hat is truly great . . . which appears time and again as if fresh before our eyes; which is difficult, or rather, impossible for us to put out of our mind; whose memory appears to be continuously, and apparently indelibly, impressed on our hearts.”4

These claims for the transfixing effects of sublime oratory or art raise many questions. Longinus devotes the greatest part of his treatise to a discussion of the means by which they are achieved: the famous analysis of the five sources of the sublime, which includes the power of grand conceptions, the inspiration of vehement emotions, the proper construction of figures, the nobility of language, and a dignified and elevated arrangement of words. The resulting sublime “elevates us and stays in the mind.”5 Grand conceptions and vehement emotions are produced by means of phantasiai (visualizations). As Longinus explains, “[T]he term phantasia is applied in general to an idea which enters the mind from any source and engenders speech, but the word has now come to be used predominantly of passages where, inspired by strong emotion, you seem to see what you describe and bring it vividly before the eyes of your audience.”

Longinus refers here to the well-known rhetorical doctrine that the maximum force of persuasion is exercised when the orator makes his audience forget that they are listening to his words and instead see before their mind’s eye what he describes. He continues: “That phantasia means one thing in oratory and another in poetry you will yourself detect, and also that the object of the poetical form is to enthral [ekplexis], and that of the prose form to present things vividly [enargeia], though both indeed aim at the emotional and the excited.”6

Most followers of and commentators on Longinus explain this process of visualization resulting in vivid presence or enthralment by means of an account that draws on the human tendency to experience emotions expressed in a way they recognize by other human beings or their representations. Cicero and Quintilian had already drawn attention to the universally recognized expressive power of gesture and facial expression. As Thijs Weststeijn shows in his essay for this volume, Franciscus Junius drew on the ekphrastic writing of the Philostrati to explain the process of emotional empathy that is excited by representations of emotions felt to be lifelike.

Enargeia

In a recent study of the concept of enargeia Ruth Webb has argued that this concept should not be understood as has traditionally been done in terms of its result, as the somewhat mysterious power of words to convey images that enter into the mind of the listener to excite emotions.7 Instead, enargeia is the result of a correspondence between the orator’s power to use words that can excite in the mind of the public visual images; and the public’s power to visualize what is represented so vividly. As a result the public is led to believe that it experiences at firsthand what is represented in words or images. Vivid speech therefore does not conjure up, magically, the living presence of the person or situation described, but excites in the mind of the listener memories that allow him or her to visualize what is described. Thereby presence is not recreated, but the experience of seeing what is described. Similarly, statues or paintings do not by their vivid lifelikeness miraculously dissolve into the living being they represent. Instead, they as well excite images in the mind of the viewers that are animated by their memories of similar situations and living beings, and thus recreate not their presence, but the experience of their presence. The living being is not recreated, but the experience of seeing it, by means of phantasia. This, Aristotle would say, is the result, literally the impact or impression, of a sense perception.8 Vivid images, like vivid words, trigger memories that feed mental images and thus make us relive the experiences of living beings while looking at their marble representations. In other words, although enargeia is a form of mimesis, like the visual arts or the theater, its effect on the viewer is not based on its lifelikeness, but on the power of words to activate the experience of seeing in the listener.9 As Ruth Webb elegantly puts it, “Plutôt que faire voir une illusion, [l’enargeia] crée l’illusion de voir.”10

The rhetorical understanding of enargeia, based on Aristotelian and Stoic views of memory and perception, thus offers an important clue to understanding why an audience can react as if they are looking at a living being instead of listening to its description or looking at its representation. Works of art in the rhetorical view are externalizations taking the place of the orator’s words, or the phantasiai in the artist’s mind, that by their vividness trigger memories in the mind of the viewer of living beings. When viewers attribute life to a work of art, the experience of looking at a living being is recreated while looking at it, just as the work of art itself recreates such a being.

Ekplexis: Terrifying, Shattering, and Petrifying

So much for enargeia. But what about ekplexis, which for Longinus was the vivid effect reached by sublime poetry? It is a distinction with important implications for the arts, since they were considered in antiquity and the early modern period to be more akin to poetry than to prose.11 Even though it might be putting too much weight on Longinus’s pairing of prose with enargeia and poetry with ekplexis, I do think it worthwhile to pursue the poetical variety of the sublime, because it may tell us more about the nature of the sublime in the arts, and because Dutch varieties are particularly telling. We also move here from theoretical accounts of the sublime to its figurations, because Netherlandish artistic literature, as far as I can see, is rather silent about the striking, terrifying, or even paralyzing and petrifying variety of the sublime.

Enargeia and ekplexis have very different etymologies and hence connotations. Enargeia is derived from argos, a strong light, comparable to the almost white flash of lightning in the Mediterranean, or a spotlight. Homer uses it to describe the epiphany of the Olympian gods. Ekplexis is derived from ekpletto, which means to strike, confound, paralyze, or render somebody beside themselves with fear, surprise, or amazement, a much more negative effect than the shining vividness enargeia evokes.12 Longinus pairs enargeia with prose, and ekplexis with poetry. This distinction alerts us that the effect of sublime phantasia is not simply a very intense variety of enargeia; it may also turn out to be much more negative, threatening, unsettling, or even petrifying.

In Peri hypsous these terrifying aspects of the sublime are illustrated repeatedly by the rhetorical powers of Demosthenes, who, as Longinus describes it, “with his violence, yes, and his speed, his force, his terrifying power of rhetoric, burns, as it were, and scatters everything before him, and may therefore be compared to a flash of lightning or a thunderbolt.” And, he adds, at the end of the surviving text, “You could sooner open your eyes to the descent of a thunderbolt than face his repeated outbursts of emotion without blinking.”13 The brilliant illumination of enargeia has here turned into the shattering flash of ekplexis.

The term Longinus uses here to define the awe-inspiring, terrifying aspects of the sublime is to deinos, meaning the terrible, awe-inspiring, or forceful but also the excessively or incomprehensibly crafty or virtuoso. He briefly mentions this when discussing Homer. For a more extended discussion, which connects ekplexis with the terrifying effects of speech, we have to turn first to the treatise on style long believed to be by the rhetorician Demetrius of Phaleron, a student of Aristotle, and now generally dated around 150 bc.14 Unlike the authors of the majority of rhetorical handbooks he does not distinguish three kinds of style (elevated, middle, and low), but four: the grand, elegant, plain, and forceful (deinos) style. It is the last variety that concerns us here, because Demetrius observes that the effect of this style is often to transfix and shatter the audience with fear mixed with awe or admiration. Combinations of hyperbole and allegory (in the sense of allegorese) for instance achieve this effect:

This is an example: “Alexander is not dead, men of Athens: or the whole world would have smelled his corpse.” The use of “smelled” instead of “noticed” is both allegory and hyperbole; and the idea of the whole world noticing implicitly suggests Alexander’s power. Further, the words carry a shock [ekplektikon] . . . ; and what shocks is always forceful, since it inspires fear.15

To deinos is also, like the sublime, ambivalent. It inspires fear mingled with admiration but can also consist, according to Demetrius, of the terrible or horrible mixed with the ironic, the comic, or the grotesque.16

This combination of characteristics—the fear-inspiring, the terrible, the grotesque, or even comic—which result in an effect of shattering or transfixing the public, can also be found in one particular group of mythological figures: the Gorgons, and chief among them Medusa. As Giovanni Lombardo has recently suggested, it is precisely in accounts of these sisters and their actions that we find the complex of terrifying awe that arrests the public, which Demetrius and Longinus tried to describe with the terms deinos and ekplexis and which is more usually associated with Burke’s much later redefinition of the sublime as the terrible that at the same time fascinates.17 The monstrous aspect of the Gorgons is often described as deinos; the petrifying agency of their snake hair and gaze as ekplexis or kataplêxis.18 In a highly original twist, Demetrius observes that such mixtures of the terrifying with the comic, the ironic, or even the graceful are often most effective in captivating the audience. Homer is the past master of producing such phoberai charites (fear-inspiring graces), for instance in the horrible gloating with which Polyphemus announces the order in which he will devour Odysseus and his comrades.19

Medusa as the Original Sculptress

Armed with all this knowledge we can now return to Dutch accounts of Medusa. Rubens was not the only artist to produce literally stunning versions of this figure, nor was Huygens the only viewer who left an account of the impact of these images. Other versions of Medusa in the Dutch Republic also left their viewers fascinated but terrified, torn between a desire to gaze into her eyes and the impossibility of leaving the scene. The Dutch eccentric nobleman and poet Everard Meyster for instance, in his panegyric on the new Town Hall of Amsterdam, describes the stunning effect of looking at Quellinus’s Medusa in the Vierschaar (fig. 2):

. . . the infernal monster

Erynnis, and Medusa, had wanted to tear us apart

and trample us while still alive; we can hardly remain on our feet and tremble,

when we think of it, and methinks, they still follow us.20

In the Mengelrymen of Pieter Rixtel—the poem which has a central role in the contribution of Lorne Darnell in this volume—the Town Hall herself speaks, brought to life by the art of Berckheyde (fig. 3). The poem plays on the entire gamut of sublime topoi, from the elevation of the building into the skies to its ambition to embrace the entire circle of canals and its power to instill higher emotions in the money-minded Amsterdam merchants. But the building can also petrify:

When the Sun caresses my head,

And plays through the Gold, and Marble Statues,

No curious spectator can bear in his eyes

the radiance of the white Alabaster,

but stands, gazing at the stone, as one

who himself has been transformed into Stone.21

Like Medusa’s original victims, these viewers fear they have become petrified. In these cases of ekplexis, words are not the means by which the sublime effect is achieved. Nor is it vivid lifelikeness in itself, or the expression of emotions in such a way as to force the viewer to empathize, because that would simply lead to a horrified rejection, particularly so since most Medusas produced in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth-century present her as a somewhat masculine old woman. They never follow, as far as I have been able to see, the Praxitelean model representing a handsome young woman that fascinated viewers so much in the decades around 1800.

Medusa as Pygmalion’s Dark Double

To understand sublime petrifaction and the questions it raises, we need to turn to its source: Ovid’s retelling of the myth of Medusa, and in particular the way in which he fashions it as a counterpart to the myth of Pygmalion. Ancient Greek myths often expressed desires and fears for images that are not discussed so fully in artistic theory. Two among them explore the precarious borders between a lifeless image and the living being it represents, the viewer’s desire that an image lives, and fear of its powers: those of Pygmalion and Medusa.22 Ovid’s retelling of the story of Pygmalion presents the sculptor’s desire that his creation come alive, and that he can have an affair with it, a narrative shown with unparalleled explicitness in Hans Speeckaert’s Allegory of Sculpture of 1582 (fig. 4). His account dwells insistently on the tactile experience of statues, when he describes how the sculptor touches the ivory, feeling and caressing it in the hope that it might turn out to be alive, and easing himself into this illusion. Persuaded by his own artistry, Pygmalion is inflamed with desire:

Indeed, art hides his art. He marvels: and passion, for this bodily image, consumes his heart. Often, he runs his hands over the work, tempted as to whether it is flesh or ivory, not admitting it to be ivory. He kisses it and thinks his kisses are returned; and speaks to it; and holds it, and imagines that his fingers press into the limbs, and is afraid lest bruises appear from the pressure.23

When he returns home from sacrificing to Venus and praying her to give him a wife similar to the statue, “for he dares not ask for an ivory virgin,” he kisses the statue again; but this time, her body grows soft and warm under his caresses.24 Startled, he again explores her body, and feels how her veins throb with life under his hand: “corpus erat,” the narrator exclaims, she has become a living body.

A very different tale of the life and agency of statues is told in the story of Medusa. In the Metamorphoses Perseus recounts it as an episode in the tale of how he rescued Andromeda and vanquished Phineus, her intended bridegroom. It has rarely been noted that the Gorgon is here presented as a kind of anti-Pygmalion, petrifying where the sculptor animates. The countryside surrounding the home of the Gorgons is described as a statue garden, full of the petrified victims of their gaze. Later on, after Perseus has decapitated Medusa and uses her head to defeat Phineus and his comrades, Ovid employs words to describe their petrifaction that are usually associated with statuary: “Thescelus became a statue, poised for a javelin throw”; “there he stood; a flinty man, unmoving, a monument in marble”; “Astyages, in wonder, was a wondering marble.” Finally, Phineus sees the simulacra, the stone statues of his comrades in arms, and calls their names. Like Pygmalion he does not believe what he sees and touches their bodies because he fears their metamorphosis, only to realize that they have been turned into stone. “They were marble,” he cries out, “marmor erant” in a clear echo of Pygmalion’s “corpus erat”:

[Phineus] sees them all,

All images, posing, and he knows each one

By name, and calls each one by name, imploring

Each one for help: seeing is not believing,

He touches the nearest bodies, and finds them

All marble, all.25

Representations of Medusa as a petrifying sculptress are not very frequent, but some seventeenth-century versions, such as the one by Sebastiano Ricci (shown here) and a number of Dutch versions to which we will return, play on the similarities between her petrifying powers and those of the sculptor by locating this scene in a statue gallery (fig. 5).

Ovid’s version of the Medusa myth figures the ambivalences surrounding the agency of art when it becomes very close to living beings in its power to fix and petrify, and in particular in its suggestion that sculpture is an act of petrifaction that can become uncomfortably close to Medusa’s paralyzing gaze. Here she turns out to be a sculptor, but not an entirely benign one. Very few studies have distinguished this aspect of the myth, with the notable exception of the French ancient historian Françoise Frontisi-Dutroux, who has drawn attention to what she calls the paradigm of ikonopoesis or figuration presented by the myth.26 First, the Gorgon’s petrifying gaze, changing living beings into lifeless statues; second, Medusa’s figuration on the reflecting mirror of Perseus; and third, the petrifaction resulting from a confrontation with that mirror image. These three kinds of figuration, or image making, all thematize the agency of art and the dangers of looking. Viewers die, petrified by the power of Medusa’s gaze, or, one might say, they die by representation. Underlying these Medusean paradigms of figuration and petrifaction is an uneasy awareness that the relation between a living being and its image is not a matter of harmless distancing or abstraction through representation in another medium. It is an ambiguous, precarious relation, in which inanimate images turn out to possess the same agency as the living being they represent.

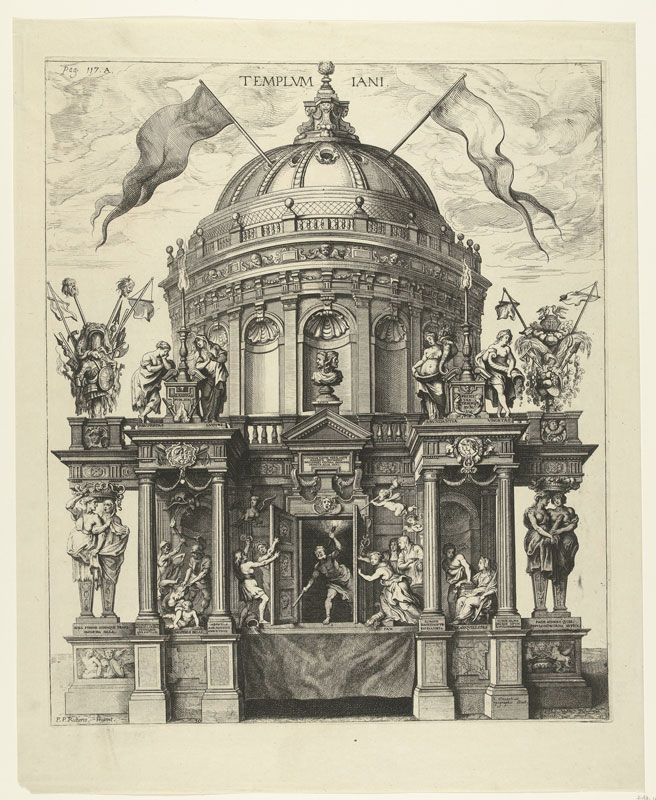

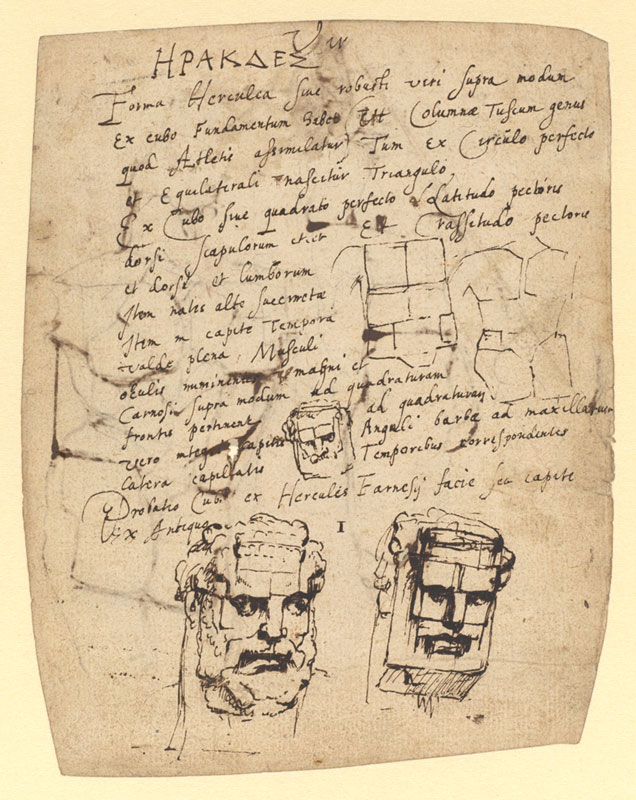

The closeness between the sculptor’s act and Medusa’s petrifying gaze is often thematized in the art of the Low Countries. Rubens often plays on it, for instance in his designs for the Pompa Introïtus Ferdinandi (fig. 6 and fig. 7). As I have argued elsewhere, many of the designs he made for the gates play on the theme of animation and petrifaction and the difficulty of discerning whether the deities, grotesques, or mythological beings he includes in his gate designs are living beings on the point of being petrified or statues that are so vivid that they come alive.27 This theme can be traced back to sixteenth-century work done at Fontainebleau. In the Grotte des Pins, for instance, human forms gradually emerge from the rustic stones, suggesting first, when looked at from left to right, the gradual stirring of living forms from inanimate stone, and then their gradually subsiding into stone again (fig. 8).28 In Primaticcio’s decorations of the rooms of the duchesse d’Etampes the caryatids framing the paintings and surrounding the herms and rams’ faces are so vividly sculpted that they seem to step out of the wall, move into it, touch the frames, and interact with each other and the viewer (fig. 9). In fact it is difficult to tell whether we are looking here at a very vivid sculptural representation of human figures, or at the representation of petrified human beings becoming alive again. There is also a drawing associated with Jacopo Zucchi, probably made for Fontainebleau, representing Perseus killing Medusa, which figures in a very insistent manner the closeness of sculpting and petrifying (fig. 10). In Rubens’s unfinished treatise as well, some of the drawings of male torsos reduce the body to a combination of blocks—or reveal these to be its underlying essence (fig. 11). The Cabinet des Estampes of the Louvre has a drawing by Leonaert Bramer showing Perseus brandishing the head of Medusa, in which the victims have become statues (fig. 13). Similarly, a painting (ca. 1650) in the National Gallery formerly attributed to Poussin, but now considered to be by the Flemish painter Bertholet Flémalle, shows the petrified victims of Phineus in the attitudes of the Niobids that could be seen in the Villa Medici in Rome (fig. 14).

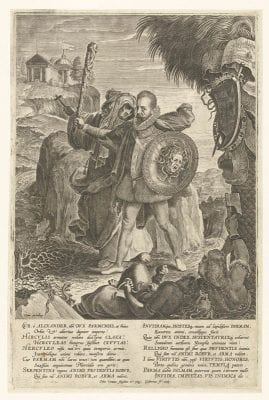

Many images of Medusa petrifying her victims made in the Low Countries show an allegorical setting, in which she is used to confront Invidia or Impietas, as in Rubens’s designs for the Pompa Introïtus Ferdinandi, or the allegory by Otto van Veen of 1585–92, showing the duke of Parma as the defender of the Catholic faith, reducing Envy to a broken statue, with his shield displaying the Gorgon’s head (fig. 15).

But the most intriguing images of Medusa’s petrifying acts can be found in illustrations to Ovid’s retelling of the myth. The German illustrations by Johann Ulrich Kraus, for instance, are extremely rich but fall outside the scope of this volume of essays. In the Dutch Republic, the illustrated translation by Vondel is a particularly interesting case. Unlike van Mander, who very much dwelt on the moral aspects of the myth, retelling it as a cautionary tale about the dangers of lust, Vondel follows Ovid quite faithfully but adds to the gruesomeness of the battle beween Phineus and Perseus by his rather plastic choice of words: “the turmoil of battle” (het barnen van den strijt); shoot a thunderbolt into a body (een’ schicht naer ’t lyf).29

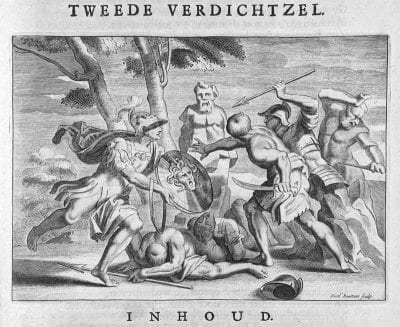

As in Ovid, the enemies of Perseus perform a reversal of Pygmalion’s behavior, or of that of early modern art lovers: he touches the statues in the hope that they are still alive, just as art lovers of the same period touch them and speak to them to test whether they are living beings or just images.30 The illustrations are rough copies of the images by Antonio Tempesta for the translation by Pieter de Iode published in Antwerp in 1606 and do not dwell on the petrifaction of Perseus’s images. The images made by Frederik Bouttats after an unknown artist for the 1703 edition are more telling: here the victims are transformed into hermlike statues, which, according to some Greek historians, were among the earliest cases of freestanding statues (fig. 16).31

Conclusion

In the passages from Junius and van Hoogstraten quoted above, the sublime is described, much more explicitly and insistently than in Longinus’s text, as the power of images to impress themselves upon the mind and remain there. The listener or viewer is transfixed or tongue-tied. This effect, as we have seen, can be related to Longinus’s distinction between the aims of poetry and prose. Prose, as we have seen, employs the strategy of enargeia; poetry that of ekplexis, and the visual arts, which are closer in character to poetry than prose, also aim for the shattering variety of the sublime. In itself, this aspect of the sublime already calls up an association with Medusa. But what is the point of comparing Medusa to a sculptor, of presenting her as the dark double of Pygmalion, and the witnesses to her deadly agency as benighted art lovers who look not for life in art but for life in dead stone? Why suggest, as in the Fontainebleau material, Rubens’s designs, or the Vondel illustrations mentioned above, that the artistic ideal of animation, of endowing statues with the living presence of enargeia, can actually turn into the process of petrifaction, visited upon mortals by the gods, as in the case of Niobe, or part of the natural process of growth, flowering, and decay, as shown in many art works in Fontainebleau?

Sometimes the Medusa myth is interpreted as a fable about the artistic representation of horrors as a way of making them bearable or of warding off their danger by petrifying them into a work of art that can look at us but cannot hurt us. Thus it becomes an instance of the aesthetic paradox that Aristotle identified, when he observed that we enjoy looking at representations in art of situations, persons, or events that would fill us with horror, fear, or disgust if encountered in real life.32

But in the cases discussed here something else is at stake. These couplings of animation and petrifaction tell us something about the unease viewers felt when confronted with extremely vivid cases of lifelikeness, as in the case of the Town Hall Medusa, or the Rubens Medusa that Huygens saw. In such cases, one might argue, enargeia becomes ekplexis: the clear shining spotlight revealing vividness becomes too strong and shatters the viewer. The image no longer observes the boundaries of reality but moves into the realm of fiction, if not nightmares. In early modern artistic theory this phenomenon is hardly ever addressed. Instead, the fascination for statues which are so vivid that they fix the viewer and rob him or her of speech and movement is figured by means of representations of the Medusa story in which she is likened, almost surreptitiously, by means of the appearance of her victims, to a sculptor. What we would now call the agency of art cannot be historicized simply by comparing it to the persuasiveness of art as defined in terms of its enargeia. To trace, in historical terms, something of the uneasy fascination and deep fear that art can inspire as well, we need to turn to those images that present to the viewer in the most direct manner the sublime power of art to stay in the mind and transfix the viewer: the gaze of Medusa and its effect on her beholders.