In 1682, the highly regarded artist Theodoor Cornelisz van der Schuer (1634–1707) painted a canvas for the boardroom of the plague hospital in Leiden. He transformed well-known depictions of the plague to create an image of an unspecified hospital in a timeless setting. More than simply an image of a hospital, the painting is also an allegory of human dependence on God. Focusing on the plague-stricken figure of Charity, the allegory visualizes moral ideas that were disseminated in a 1526 tract on poor relief written by Juan Luis Vives. In the painting, the plague becomes a symbol of human deprivation, and by depicting Charity as a plague victim, van der Schuer projects the idea that humility is an essential part of charity. Since Vives was widely known throughout the seventeenth century, we may assume that his ideas were familiar to the hospital’s regents. And although van der Schuer disguises Charity as a plague victim, visitors to the boardroom probably recognized the personification nevertheless. Images of Charity were ubiquitous, especially in the context of hospitals, where they reflected the actions of the regents donating their time and dedicating their skills to the destitute. In reality, the hospital probably did not ever house plague victims; although the disease remained a constant threat, the institution served different kinds of patients. Combining a scene of the plague with a broad-reaching allegory, the painting proved relevant for decades to come.

In 1682, the artist Theodoor Cornelisz van der Schuer (1634–1707) painted his Allegory of Human Deprivation as a chimneypiece for the boardroom of the pesthouse, or plague hospital, in Leiden (fig. 1). This little-studied painting depicting plague sufferers merits a closer look, both because of its painter and its subject. First, it was painted by a highly regarded artist who had established an international reputation before settling in The Hague in 1666. Van der Schuer earned important commissions in his time, but until now he has not received any significant level of modern scholarly attention. Second, the subject of the canvas, the plague, is unusual in a painting designed for a hospital, and particularly unusual for the Northern Netherlands, even though van der Schuer used well-known sources to shape his unconventional image. Most significantly, instead of depicting Charity in the usual way—as an idealized female figure caring for others—he transferred her characteristics to the care recipient: a plague victim. The painting has been used as illustration in publications on the plague and pesthouses, but its artistically creative qualities have been overlooked, as has its moral message.

Part of this essay uncovers van der Schuer’s many sources, both literary and artistic. Referring back to works by prominent artists, van der Schuer used different models to shape his vision of the plague. The result probably fascinated the painting’s educated audience, primarily the regents of the hospital, who may (or may only partially) have recognized the visual references. But the image is more than an assemblage. Further examination of van der Schuer’s design reveals a well-considered iconography comprising three consecutive stages of the disease, leading to inevitable death. It also includes a prominently placed personification of Charity. The regents would have understood Charity to be an appropriate subject for a canvas to hang in a charitable institution. She was a common iconographical personage for hospitals, orphanages, and homes for the elderly, and she was included as a subject for chimneypieces for many of these institutions. The artist used the regents’ likely familiarity with the personification to transform traditional plague imagery. He created a scene that stimulates reflection not just on the misfortunes of plague victims but on the needs of humankind. I will argue that the disastrous effects of the plague, as depicted in Theodoor van der Schuer’s allegory, conveyed human deprivation.

This paper first outlines the context of the commission, paying particular attention to the history of Leiden’s plague hospital. I also consider the motives of the regents in choosing an eminent painter such as Theodoor van der Schuer. This is followed by a discussion of the painting and the models that van der Schuer used in shaping his vision of the plague. Finally, I will demonstrate that the image carries a deeply moral message, warning the hospital’s regents against pride. The theme of the canvas reflects ideas about the moral justification of poor relief that had been disseminated by the Bruges-based humanist Juan Luis Vives and popularized in Holland by Haarlem’s city secretary Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert, among others. All the elements—from the bright red dress of the plague victim to the ominous, dark cloud in the upper part of the canvas—underscore the message that God is responsible for human misfortune and is the only source of charity. The allegorical content gave the painting continuing relevance for Leiden’s plague hospital, built to house plague victims in times of epidemics, even though it was probably never used as such when the painting was installed.

Leiden’s Plague Hospital

Various plague outbreaks in Holland—especially in 1557–58, 1624, 1635–36, 1654–55, and 1664—called for specialist hospitals, or pesthouses.1 These institutions housed the large numbers of plague victims that could not be isolated in their own homes without danger of infecting family members. There was a need in Leiden for such a facility. As early as 1577, in his Poor Report (Armenrapport), Leiden’s City Secretary Jan van Hout (1542–1609) had already made the case for a city plague hospital, “which Leiden cannot do without.”2 In the Poor Report, van Hout argued for a centralization of some of the city’s charitable institutions under the supervision of Leiden’s town council. Although it is challenging to pinpoint concrete influences, scholars have connected van Hout’s plans to Juan Luis Vives, who considered poor relief a responsibility of city government.3 Vives’s De Subventione Pauperum sive de Humanis Necessitatibus (On Assistance to the Poor, or the Needs of Mankind) was translated into Dutch for the second time in 1566, shortly before van Hout wrote his Poor Report.4

Another recognized source of inspiration was the work of van Hout’s close friend Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert (1522–1590).5 Coornhert became city secretary of Haarlem in 1562, but he ran into trouble with the Spanish authorities after the iconoclastic outbreaks because of his close ties with William of Orange. During a relatively short period of imprisonment in The Hague, he wrote about disciplinary measures against crime and poverty. The manuscript, called Discours onder verbeteringe van den verstandigen (Discourse on the Improvement of the Wise), was finished in 1567, and an augmented version was published under the title Boeventucht (Discipline of Knaves) in 1587.6 Considering that van Hout and Coornhert were friends and city secretaries of Leiden and Haarlem, respectively, it seems safe to assume that they discussed their ideas about indigence and poor relief at length. It has also been suggested that Coornhert, in turn, adopted many ideas of van Hout’s Poor Report when he wrote his revised and augmented version of his Discours.7

After finishing the Poor Report, van Hout remained closely involved with Leiden’s care facilities. The first arrangements for a plague facility were made in 1596, when a room in St. Cecilia’s hospital was renovated to house plague victims.8 The idea of a standalone, purpose-built structure was put forward by van Hout, along with the suggestion for a lottery to cover the costs. The lottery was modeled after a comparable 1564 effort in Delft, organized to pay for a plague hospital.9 The large-scale fundraising event in Leiden lasted longer than a month and was preceded by a rhetorician competition. Van Hout himself wrote a lottery play (Loterijspel) for the occasion.10

But it was only after the disastrous epidemic of 1635–36 had hit many towns in Holland that the members of Leiden’s town council at last decided to turn words into action. They ordered a temporary wooden hospital to be built outside the city walls to house indigent plague sufferers, although a more permanent accommodation was probably already on their minds for the near future. In 1657, after yet another virulent outbreak of the plague in Leiden, they decided to execute a replacement building in stone.11 For inspiration, Leiden’s town council turned toward Amsterdam. Charged with the task of advising the hospital board, the city’s treasurer visited a plague hospital built outside Amsterdam’s city walls in the 1630s. Amsterdam’s hospital, with its square plan and moat, provided the model for Leiden’s pesthouse. Construction of Leiden’s hospital started in 1658 and was finished in the summer of 1661.12

A hospital of this shape and size also required decoration. Charitable institutions were sources of civic pride in the seventeenth century, worthy settings for important commissions by prominent artists. Their prestige reflected a moral superiority: the presence of charitable institutions raised the city onto a higher moral plane. As the famous Amsterdam poet Jan Vos wrote, when he described the newly erected almoners’ orphanage in Amsterdam:

The house of the rich man glistens in earthly mist But the one built for the poor rises through the clouds, And shines in the face of Christ’s chivalry: It provides, for the souls of those who build it, stairs to climb to the exalted building of the Most High.13

“[T]he rich man” was made to feel responsible for those who were less fortunate (the poor) and urged to invest in care facilities. From Vos’s verses, it is clear that the building reflected positively on those involved in its conception, construction, and management. It even suggests a spiritual reward for “the souls . . . who build it.” Correspondingly, the founders and regents of these institutions often displayed their names, portraits, or heraldic devices prominently in, or on, the building. Adhering to these practices, the coat of arms of the regents of Leiden’s hospital appeared on the façade, clearly visible to those passing by. The members of Leiden’s elite wanted to be associated with the edifice and remembered for their efforts, both during their lifetimes and after they died. Portraits and the regents’ coat of arms were often included among the decorations of the boardroom, sometimes on either side of the chimneybreast. Elements that referred directly to the regents literally framed chimneypiece paintings like van der Schuer’s Allegory of Human Deprivation. The building—inextricably bound up with the institution inside—became part of the regents’ identity as much as that of the city.

Ties between the hospital and Leiden’s town council were close, both during and after the hospital’s construction. This was also true when the board of regents commissioned van der Schuer to paint a canvas for the boardroom in 1681–82. Dirk van Hoogeveen and Johan de Bije, appointed to the board in 1679 and 1680, respectively, were also members of the town council.14 Hospital regents usually came from rich and well-connected middle-class families. A wealthy background was a requirement, because a hospital position did not generate much income. Jacob Drabbe, for example, who was appointed regent of Leiden’s plague house in 1676 and probably involved with the commission of the painting, came from a rich family of soap-boilers.15

Esteemed artists often participated in the construction and decoration of such buildings in Leiden. During the final stages of completion of the city’s pesthouse, the sculptor Rombout Verhulst (1624–1698) was asked to carve a gable stone. He probably started the work in Leiden after he finished assisting the sculptor Artus Quellinus with his work on Amsterdam’s city hall (later the Royal Palace on the Dam).16 In Leiden, Verhulst created a large relief with life-size figures, almost doubling the height of the entrance (fig. 2). The dramatic scene depicts a mother pulling out her hair because a Fury, symbolizing the plague, has seized one of her children.17 Despair pervades the scene. The woman’s face is contorted in agony, while her second child grasps his mother’s dress in terror. The prominent signature “R Verhulst 1660” in the lower right ensured that the involvement of the sculptor would not go unnoticed by passersby.

For their chimneypiece, the regents chose an artist who fit the prestige of their plague house. After an apprenticeship with the French painter Sebastien Bourdon in Paris, Theodoor van der Schuer went to Stockholm with his teacher. A signed agreement between Bourdon and van der Schuer, dated 1652 and covering the conditions of their trip to Sweden, is kept in the national archives in Paris.18 From 1661 to 1665, van der Schuer was in Rome, where he entered the service of Queen Christina of Sweden. This international career probably helped him make a name for himself after he established himself in The Hague in 1666. He worked for highly placed people, such as stadtholder Willem III of Orange (1650–1702) and members of the court, and he received large commissions to decorate the boardrooms in the town halls of Maastricht and The Hague.19 In 1682, he took on a prestigious commission to decorate Leiden’s university tribunal (vierschaar), later the burgomaster’s room in the town hall.20 He finished the piece for Leiden’s plague house in the same year. He proudly signed and dated the work in the lower left: “Theod: van der Schuer, Fect Ao 1682.”

Entering the boardroom of a hospital, visitors would expect to see a painting with an elevated subject and a moral message. The boardroom was a semipublic room where the regents assembled and received guests. This means that regents saw the painting every time they discussed hospital matters, and so did their visitors. The painting therefore served as a calling card to the outside world; it was an image that represented the regents’ activities. Usually, chimneypieces in boardrooms depicted allegories representing the work performed inside the hospital walls, and these paintings often included the focus of care: the sick, the poor, the elderly, orphans. For example, Adriaen van der Werff inserted an elderly man into an allegory of Charity for the former Holy Ghost hospital, the old men’s home, in Rotterdam; painted in 1702, it in turn referred back to a design from the 1690s.21 In 1682, the Delft-based painter Cornelis de Man (1621–1706) designed an allegory of the virtuous life for Delft’s Chamber of Charity, a municipal relief institution (fig. 3).22 De Man’s painting includes a personification of Charity in the guise of a pauper. Placed on the receiving end of the chain of almsgiving, this figure of Charity has much in common with van der Schuer’s image.

As a specialist in allegorical scenes, van der Schuer was well suited to meet the expectations for such an elevated subject. For the vestibule ceiling of Maastricht’s town hall, van der Schuer had designed a complex arrangement depicting Good Government, and for Leiden’s university tribunal he had produced two overdoor paintings with the goddess Minerva and a personification of Academia.23 If one identifies the scene of van der Schuer’s Leiden pesthouse chimneypiece as merely a hospital interior, as some current-day scholars have done, some of its most important aspects would be disregarded.24 Close investigation reveals that the subject is, like the previous examples, an allegory, but it is one that does not initially appear as an allegory because it is so intricately interwoven with a dramatic scene of the plague.

Depicting the Disease

In the foreground, van der Schuer depicts a mother and child in great distress. With these two heartbreaking figures, it seems as if van der Schuer resumes the story where the sculptor Rombout Verhulst left off (see fig. 2). While Verhulst’s gable stone shows a mother who loses one of her two small children to the plague, van der Schuer depicts one child crying over his dying mother. The mother has fallen ill, leaving the child by himself. These dramatic details compelled lasting admiration, judging by a contribution to a 1762 book on Leiden’s monuments. In that book, the Leiden-born artist Frans van Mieris described van der Schuer’s painting at the pesthouse, “depicting a woman who has died from the plague there,” adding that the work of art is “impossible to look at without being deeply affected.”25

For inspiration, van der Schuer consulted well-known images of the plague. The man in the hospital bed behind the main figure refers back to a painting by Pierre Mignard (1612–1695). Van der Schuer studied Mignard’s design for an altarpiece for San Carlo ai Catinari in Rome around 1647 (fig. 4), though the French artist lost the competition for the commission to the Italian painter Pietro da Cortona.26 When van der Schuer was in Rome in 1661, da Cortona’s altarpiece for San Carlo was already in place. Nevertheless, Mignard’s design had been well received, and images of it were readily available. They circulated in a variety of painted copies and prints, including those made by engraver François de Poilly, shortly after its production.27

In his painting of St. Charles Borromeo ministering to plague victims, Mignard included a foreshortened figure that lies in a bed placed at an angle to the viewer. The sick man turns his head and stretches out his right arm toward the saint. Van der Schuer depicted his own bedridden plague victim in a similar pose, creating the same illusion of depth in a crowded space. The bed is placed at the same angle, and the patient’s head is wrapped in the same white cloth.

Both figures are sick, but van der Schuer’s patient seems worse off than Mignard’s. His eyes are almost closed, and he has a black-edged spot on his arm. The man is dying, as the sad look upon the woman’s face seated next to him makes clear. She holds her head in her hands as a gesture of grief. The disease has progressed to a stage beyond immediate assistance, and the woman can only wait for the inevitable outcome. The final phase in the progression of the disease is visualized directly behind her. A man carries away the body of a recently deceased person for burial. The man moves in front of an arcade leading to a clearly lit area. The contrast in lighting underlines the importance of this small figure group.

The most prominent figure group in the painting is that of the mother and child, a grouping van der Schuer may have featured because of its familiarity. The combination is a topos in literary descriptions of the plague. When Theodorus Schrevelius (1572–1653) described the plague in Haarlem, he wrote about “suckling children . . . torn from their mother’s breasts,” depriving them of sustenance.28 Similarly, in his account of the great plague in London in 1665, Daniel Defoe mentioned “living infants being found suckling the breasts of their mothers or nurses after they had been dead of the Plague.”29 A child is a representation of the needy par excellence, because he or she is helpless without parents. The motif of a child deprived both of the love of its mother and of nourishment would have exerted a powerful dramatic impact on the viewer, as van Mieris observed. Struck by the plague in his prime, the young man in the hospital bed, mourned by a woman who might have been his bride, can likewise be regarded as a literary topos.30

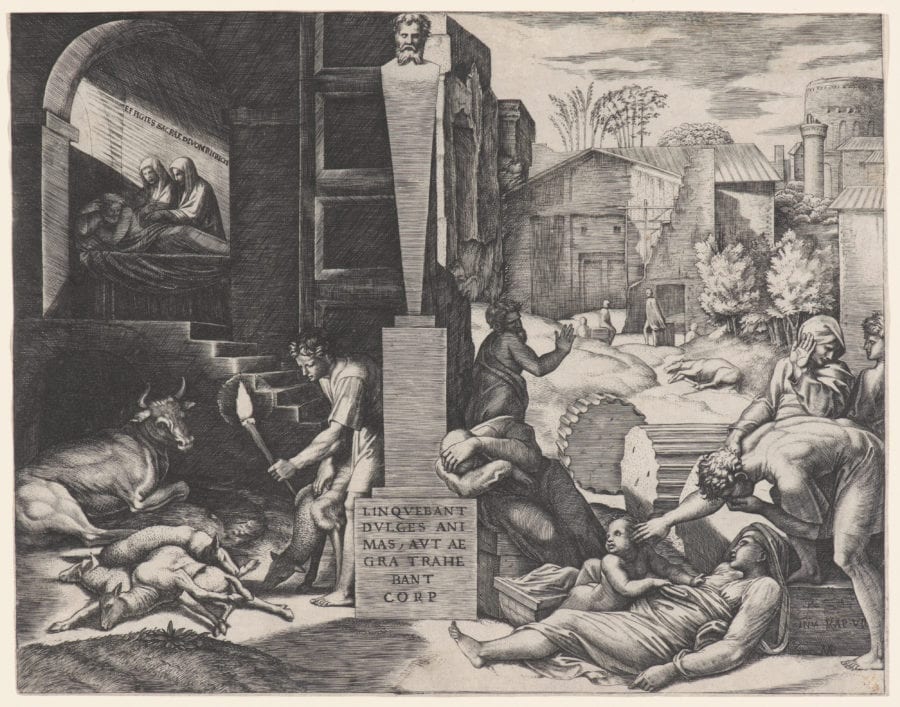

Van der Schuer also had compelling visual models for the motif of the plague-stricken mother and her child. The detail of the child that tries in vain to drink from his mother’s breast harks back to famous paintings such as The Plague at Ashdod by Nicolas Poussin (1630; Musée du Louvre). In her analysis of Poussin’s painting, art historian Sheila Barker describes the classical roots of this motif as well as its associations with the virgo lactans, or the Virgin suckling the Christ child.31 Poussin borrowed the motif from Raphael’s painting of the plague that was copied in print by the Italian engraver Marcantonio Raimondi (fig. 5). Sometimes simply referred to as The Plague, the famous print was also called Il Morbetto, or “little disease,” indicating the small size of the image. Raimondi’s print disseminated Raphael’s composition throughout Europe, including Holland.

Longstanding iconographical traditions confirm that the woman personifies Charity. The iconography of the personification had developed over the course of centuries and was formalized in the Iconologia, written by Italian author Cesare Ripa in 1593.32 In alphabetical order, Ripa describes how personifications should be depicted and what they signify. Translated into many different languages, the Iconologia found a widespread audience across Europe. It was published in Dutch in 1644. Many seventeenth-century artists used the Iconologia as a handbook to design personifications, and different paintings by van der Schuer indicate that he was familiar with Ripa’s manual.33 His depiction of Academia for the university tribunal, for instance, closely followed the figure as outlined in the Iconologia.

In van der Schuer’s Allegory of Human Deprivation, the child, the red dress, and the bare chest all indicate that this woman is Charity.34 Her bright red dress contrasts sharply with the dark, subdued colors in the rest of the painting. Ripa’s Iconologia mentions the flaming red dress as one of Charity’s defining characteristics and advises that she should be depicted with three children, in reference to the divine virtues, although she could also be depicted with one, two, or more than three children. Finally, she has one or both breasts exposed, because the act of nursing symbolizes the spiritual nourishment that comes from the love of God.35

In addition to adopting Ripa as a source, van der Schuer used other visual models to shape his version of Charity, including works of art in other hospitals. Around 1675, Gérard de Lairesse (1641–1711) designed a figure of Charity for the leper house in Amsterdam (fig. 6), where she is part of a complex allegorical scene featured on a ceiling.36 Placed front and center, she is the most prominent and important figure in the composition. Lairesse also followed Ripa’s description carefully, and some of the visual parallels between the interpretations by Lairesse and van der Schuer can be explained by their mutual dependence on the Iconologia. But the similarities between the two go beyond Ripa. Lairesse also painted Charity as a reclining figure, and the lower part of the body, with the draped red cloth, is a particular point of similarity. The position of her legs is almost identical to that of the figure in van der Schuer’s painting.

Considering its date, location, and subject, Lairesse’s ceiling provided an obvious reference for van der Schuer. He received the plague house commission only a few years after its completion. It can be assumed that van der Schuer was familiar with the work of Lairesse, who was a prominent artist at the time. Both Lairesse and van der Schuer worked for the stadtholder and his court.37 Further, the hospital’s regents may well have pointed out Lairesse’s paintings to van der Schuer. As we have seen, the town’s magistrates had already turned to other cities in their search for models on organizing charity: Leiden’s town council had raised the money for the pesthouse with a lottery, following Delft’s example, and the layout of Leiden’s plague hospital had been modeled after Amsterdam’s plague house. Since Lairesse’s Charity was produced for an institution similar to Leiden’s plague facility, it seems reasonable to assume that the board understood its relevance for the new canvas.

In addition to the painted ceiling, van der Schuer may have looked to another work by Lairesse, depicting not a triumphant figure (as in Amsterdam) but a pitiful one. The artist’s etching Niobe Punished for her Pride is dated 1668 (fig. 7). The Niobe myth was an appropriate model for showing the dramatic effects of a plague outbreak. Niobe had boasted about having more children than Leto, and her arrogance prompted Leto’s own two offspring to inflict death on Niobe’s children. Traditionally, the cause of their death was associated with a plague outbreak, represented by Diana (as is the case here) and Apollo shooting their arrows. In Lairesse’s etching, the upper part of Niobe’s reclining body has much in common with van der Schuer’s figure, especially the bare chest, the rumpled dress below the breasts, and the drapery’s positioning over her right shoulder. Van der Schuer likewise borrowed the close-up view from Lairesse in order to confront the viewer immediately with the emotions of his protagonist. Overall, the etching focuses on pride leading to a fall, a theme that is also especially relevant for van der Schuer’s painting.

Another visual reference might have been provided by Coornhert’s engraving after Maarten van Heemskerck’s The Wife Giving Alms, dated 1555 (fig. 8). The print might have suggested to van der Schuer the possibility of showing Charity on the receiving rather than the giving end of philanthropy.38 Part of a series on the virtues of a good housewife, this print shows a woman distributing bread to the poor. Seated on the doorstep is a woman with two children, raising her hand. Her prominent position in the foreground underscores her importance to the entire image. Most beggars in the print are dressed in rags, but one of her children is naked, which seems to accentuate the allegorical aspect of this figure group. Finally, the inclusion of the figure in a print series on virtues of a good wife makes the figure’s identification as Charity likely.

The Needs of Mankind

In depicting Charity in a state of destitution, both Coornhert and van der Schuer visualize ideas about poor relief from Juan Luis Vives’s De Subventione Pauperum. In this famous tract, Vives argues that poor relief is mainly a task of government; that is, the city, not the church. Under his influence, local governments’ involvement with poor relief increased. Although Vives was neither the first nor the only one to circulate ideas on centralized charity, he was unique in methodically committing these thoughts to paper and combining them with practical advice. The ongoing production of new editions underscores the continuous demand for Vives’s tract.

De Subventione Pauperum consists of two parts. The latter part contains practical advice on how to organize charity; the first part is a moralistic tract. In it, Vives argues that charity is a moral obligation. In a chapter entitled “The Needs of Mankind”—also the subtitle of the entire tract—he argues that everybody is destitute. Everybody needs something, either money, health, or intelligence, and “whoever needs another’s help is poor and in need of mercy.”39 Deprivation is therefore an instrument of great virtue, because it puts others in a position where they can help, just as God directs everything for human benefit. On the one hand, Vives argues that those who have money and status are obliged to perform acts of charity, because it is the virtuous thing to do. On the other hand, and more important here, Vives claims that everyone lacks something: the poor lack money, and people suffering from the plague lack health, but the rich and fortunate who are in a position to perform acts of charity lack something as well.

In van der Schuer’s painting, two young men covering their noses and mouths look after the figure of Charity, offering her sustenance. Reversing the roles of the privileged and the destitute, van der Schuer depicts Charity in a position of dependence. Essential here is Vives’s argument that those who lack virtue are the poorest of all. The rich, who think they lack nothing, consider themselves equal to God, an assumption that makes them arrogant and proud. They are the neediest of all, because they are the poorest in virtue. Likewise, those in privileged positions, such as the administrators of Leiden’s hospital, should realize that they, too, are dependent on others. They should combine their charity with humility, lest they make themselves guilty of pride. In this intellectual and ethical context, Lairesse’s print of Niobe, whose proud behavior caused her children’s deaths from the plague, made an ideal model for van der Schuer.

Some viewers of van der Schuer’s painting might have understood the female figure as representing the first stage of the plague, ignoring or oblivious to the reference to Charity. But others would have recognized the allegorical personification, which was one of the most common in the art of the time. To ensure identification, van der Schuer closely followed Ripa in choosing the color red for her garment, as we have seen. Ripa wrote that Charity is dressed in red, which is the color of blood, because “love continues until blood is shed.”40 Although the mother no longer has the strength to breastfeed, van der Schuer depicted the child as deprived of her milk to indicate that she has recently nursed, just as Charity does.

Furthermore, the hospital setting itself would have generated an expectation for regents and their guests to identify the figure as Charity. Personifications involving charitable acts were usually placed inside and outside of charitable institutions—as, for example, on the façade of the Holy Ghost orphanage on Leiden’s Hooglandse Kerkgracht.41 The context of van der Schuer’s Leiden canvas, prominently displayed in the semipublic boardroom of a charitable institution, helped the viewer make the connection between the female protagonist in the scene and Charity.

Viewers may also have understood the prominently depicted plague victim (Charity) as a warning against pride. That would have been especially true for those familiar with Vives’s ideas about charity and humility. Coornhert had drawn on Vives in his moralistic writings on poor relief, which were well known in Holland. Educated as an engraver, Coornhert also produced images that seem indebted to Vives. Art historian Ilja Veldman, for example, has underlined the similarities between the print series by Coornhert that depicts the virtues of the perfect housewife (see fig. 8) and Vives’s tract Institutio foeminae christianae (The Education of a Christian Woman).42 In his Boeventucht, Coornhert proposes plans to punish the able-bodied poor who refused to work; Vives was probably one of many sources for this idea.43

Coornhert’s best-remembered tract, Zedekunst, dat is Wellevenskunste (Ethics: The Art of Living Well) of 1586, has much in common with the first part of Vives’s De Subventione Pauperum, in which Vives explains his thoughts on charity and humility. In the sixth and final book of Zedekunst, Coornhert identifies humility (ootmoedicheyd) as the source of all virtues. He writes that “true humility is a treasury of all things that are good, a healer of all poisonous evil and the only source, root, and mother, yes, also the nurse and the protector of all divine virtues.”44 Coornhert used the tropes of mother and nurse, images that were commonly associated with the virtue of charity, one of the divine virtues that St. Paul mentioned in his first letter to the Corinthians (I Cor. 13:13). Like Vives, Coornhert connected humility with almsgiving and explained that everyone should realize that they are beggars. The gifts they give are not theirs (niet des bedelaars); they come from God.45 In addition, the rich have received everything they have from God, which makes them beggars, and God the only giver.

Vives’s ideas had spread into Holland via Coornhert, whose views on virtue and humility, on poverty and crime, are visualized in the aforementioned allegory of the virtuous life painted by Cornelis de Man for Delft’s Chamber of Charity (see fig. 3). De Man was appointed regent of the Chamber of Charity in 1680 and received the commission for the painting a year later.46 The image was finished in 1682, the same year that van der Schuer signed his canvas.47 Both canvases feature large personifications of Charity wearing red dresses in prominent positions. De Man, however, left no doubt as to her identity: he inscribed the word charitas on the column base behind her.48

De Man created a complex image that opposes the virtuous with the undeserving.49 A woman who is destitute, but rich in virtue, receives a loaf of bread, while another who is also destitute, but less virtuous, is reprimanded. The image connects directly with Coornhert’s ideas on crime and poverty, explicated in his Boeventucht. Considering de Man’s position as regent for the Chamber of Charity, and thus his responsibility for the distribution of bread among the poor, he probably read and discussed Coornhert’s treatise.

Unlike de Man, van der Schuer does not set Charity apart from the undeserving. His reasoning becomes obvious: the themes of crime and its proper punishment, as explained in Boeventucht, were appropriate for Delft’s Chamber of Charity, but not for a plague hospital. Looking for something suitable for a pesthouse, van der Schuer focuses instead on Vives’s idea that everybody is poor; that some “lack money, others health or intelligence.”50 To Vives, plague victims become objects of charity in the same way as those without food or money. In his Zedekunst, Coornhert uses the metaphor of a beggar to describe human destitution, and he identifies God as the only giver. For Leiden’s plague hospital, van der Schuer transforms the figurative beggar mentioned by Coornhert into a plague sufferer. The effect is the same, because, as Vives argues, a poor person is someone who lacks something, either money and food (like a beggar), or health (like a plague sufferer).

Three Stages of the Plague

In 1600, a member of Leiden’s town council asked Joannes Heurnius (1543–1601) to write about the plague. Heurnius, professor of medicine and rector magnificus at Leiden University, wrote the manual Het noodigh Pest-Boeck (The Essential Plague Book) to help the town in its struggle against the disease, as he pointed out in the introduction.51 Heurnius directed his advice explicitly to people working with plague victims, as when he mentioned, for example, that the doors of the pesthouse should remain closed during the day.52 In light of the book’s practical information on symptoms and remedies, the planners of Leiden’s eventual plague hospital almost certainly made use of it.

The prominent display of jars and bottles in van der Schuer’s Allegory of Human Deprivation may show his familiarity with strategies to fight the disease and its symptoms. Heurnius lists a large number of preventive, curative, and soothing measures, among them different substances to hold in the mouth, swallow, apply to the body, put into pomanders, or burn in order to clean the air.53 Other treatments with (and many different preparations of) roots, herbs, flowers, fruit, seeds, animals, precious stones, oils, syrups, etc., are to be prescribed once infection has occurred. The bottle with a transparent fluid beside the figure of the sick mother may explicitly refer to the pot of infused rosewater and vinegar that should be kept close to the bed of a plague victim.54

Another of Heurnius’s observations is also pertinent: the disease is caused by a “smoke in the air” (roock in de locht) that pervades all parts of the body without being seen or felt.55 “We all breathe the same air,” Heurnius states when he explains why the plague could destroy anyone.56 Although the real thing is invisible, the dark cloud in van der Schuer’s painting conveys the presence of the corrupt air that made people sick.

The plague was often visualized by angels carrying arrows or a sword.57 But van der Schuer may have found a pictorial prototype for this cloud in an engraving of the plague of the Israelites, after Pierre Mignard (fig. 9). Mignard kept the angel but exchanged the usual arrows for an incense-burner, which is more consistent with contemporaneous ideas about infectious transmission via corrupt air.58 Van der Schuer left out the angel, retaining the dark cloud alone.

Hovering over the heads of the figures in the painting, the dark cloud becomes a reminder of pending misfortune and an inescapable fate. Heurnius began his treatise with the observation that the plague is the worst disease in existence.59 The physician Hub Sysmus (lifedates unknown) also published a treatise on the plague in 1664. Besides writing that the plague is “nothing else than decay . . . of the body,” Sysmus points out that even the disease’s name signifies destruction: the word “pest” comes from the Latin depascere, meaning to destroy, signifying that the plague violently destroys all life that it takes hold of.60

At the same time, the cloud symbolizes God’s intervention.61 As such, it provides a counterbalance to the pots and jars, representing human medicine, in the foreground. Although different vehicles of transmission were considered, most people agreed—and it was confirmed in medical treatises—that God was the primary cause of the plague. In the Low Countries and throughout Europe, the plague was often thought to be God’s response to human sin and misconduct.62 As the most important cause of the plague, God was also the most important source of assistance. People could only fight the disease with his help. As Heurnius and other physicians pointed out, helping the victims without help from God is a vain exercise: “Surely without God, this cruel devouress is stronger than medicine, stronger than those providing assistance.”63

Heurnius justifies his attempt to write about plague remedies by arguing that the plague should be treated with all the instruments and knowledge available to man; nevertheless, it can never be conquered without God’s assistance.64 In addition to his Pestboeck, he wrote a much shorter work on the plague that was published in Leiden in 1624. This second volume summarizes the most effective measures, but it starts with the remark that patience and prayer are more effective than any medicine, and that medicine only works if one does not forsake God.65 Significantly, two figures are depicted on the decorated title page: a physician and a woman praying. Together, they illustrate the two necessary responses to the plague, each of great importance.

Van der Schuer further underscores the limits of human intervention by depicting the three progressive stages of the disease, ending in death. The two figures offering assistance focus attention on the crying child, whose raised arm points to the face of the woman in red. The woman signifies the first stage of the plague. Notwithstanding the wide range of measures available and the assistance offered, nothing has helped her. On the woman’s chest, van der Schuer has added a sinister dark spot. The location on the chest indicates that it is not a bubo, or swelling of the lymph nodes—these usually appeared near the ears, in the neck, under the armpits, or in the groin. Contrasting sharply with her pale skin, the black-edged spot seems to denote a carbuncle, “which usually appears on the chest,” according to Heurnius.66 More dangerous than a bubo, a carbuncle (pestkool) was a sure sign of death. Sysmus writes that “if a lead-colored circle appears around it, the sick person will soon die.”67 Indeed, in the painting, the plague seems to have progressed to a stage beyond the power of medicine.

The woman’s gaze leads away from the figures in the foreground to the man behind her. The man lying in a hospital bed and the grieving woman next to him are the second cluster of figures, representing the second phase of the disease. The stretched arm of the man finally focuses the attention on the third and final scene in the background, where a man carries the corpse of a deceased plague victim. Depicted on three planes, the three victims visualize the progress of the disease: the woman in red enters the hospital; the man in the hospital bed dies; and finally a body leaves the hospital for burial. Providing a sobering parallel to many plague treatises, van der Schuer reminds the regents that the help they offer means little, because ultimately assistance comes only from God. Further illustrating this idea, the figure of Charity accepts a bowl of sustenance from the boy who comes to her aid; however, aware that she has to rely primarily on God for help, she takes the bowl but otherwise ignores him. Her gaze is directed upward to indicate that she knows that God provides the only cure. The personification of Charity, her position of dependence, her heavenward gaze, and the ominous dark cloud—hinting at the divine origin of the disease—all help to articulate the main subject. Privileged or poor, we are all in need of help, dependent on others and on God for assistance.

Concluding Remarks

In his Allegory of Human Deprivation, Theodoor van der Schuer uses the plague to symbolize human deprivation. By depicting Charity as a plague victim, the artist visualizes the idea that charity should always be combined with humility. This idea was communicated in ethical treatises and in De Man’s chimneypiece for Delft’s Chamber of Charity, for example. Although often overlooked, the close ties between charitable institutions provide a promising point of departure when studying chimneypieces and other hospital decorations. Magistrates who were involved with the construction and renovation of hospitals turned to institutions in other cities for ideas on how to organize charity in their hometowns. Since city magistrates and hospital regents adopted the layout of other hospital buildings, they probably drew inspiration from their interiors as well.

Delft was not far from Leiden, and it seems fair to assume that the regents from Leiden and Delft may have conversed about charity. Delft had already served as an example when Leiden’s town council decided to organize a lottery to fund the new plague hospital. Cornelis de Man was regent of Delft’s Chamber of Charity in 1680 around the time that van der Schuer received the commission to paint the chimneypiece for the hospital in Leiden. Leiden’s regents may have turned to Delft for inspiration, and they may even have spoken with de Man personally. Van der Schuer may or may not have seen preliminary sketches for the painting for Delft’s Chamber of Charity, and he may or may not have conferred with de Man, who was also a respected painter. But whether directly or indirectly linked, their paintings refer back to the same sources.

Gérard de Lairesse’s paintings for Amsterdam’s leper house probably supplied models for Leiden’s plague house, but until now the parallels between van der Schuer’s image and Lairesse’s have gone unnoticed. Responding to additional motifs provided by Mignard and Lairesse’s Niobe Punished for Her Pride, van der Schuer painted an evocative picture of the plague. The scene visualizes the destructive disease that prompted the construction of a plague hospital in Leiden. The secondary figures in the scene embody the immediate assistance that people can offer the sick: they feed them, give them drink, visit them, and bury them. Drawing from different sources, van der Schuer designed an image that is simultaneously compelling and appalling.

The painting’s affective qualities can obscure its allegorical significance. But the painting, I argue, worked on different levels. On the first level, the drama of the plague scene captured van Mieris’s attention in 1762.68 The regents and those visiting the representative boardroom would have recognized the depicted plague victim as the object of their care; the plague sufferers represented the patients inside the hospital. On the next level, most of the people visiting the pesthouse would also likely have recognized the personification of Charity in the plague sufferer. Ubiquitous in hospitals, the figure of Charity provided a mirror for those involved in charity; they could identify themselves in the personification that represented their charitable work and served as a role model. On the third and final level, those familiar with the highly moralistic works of Juan Luis Vives and Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert—the well-read circles of regents, for instance—would have understood the reversal of roles, with Charity disguised as a patient.

Despite its stated purpose, the new hospital never functioned as a pesthouse. Although the plague hit Holland again in 1664, shortly after the construction of the pesthouse, Leiden would never again see another truly virulent outbreak.69 As it turned out, the hospital beds were used for other purposes. In 1672, for example, the hospital served as a care facility for wounded soldiers. Nonetheless, the plague remained topical as a theme for a work of art in the regents’ room because fear of a new epidemic remained alive. The regents stipulated that the hospital should be evacuated to make room for plague victims immediately if a new outbreak hit Leiden.70 Further, the disease remained a real threat in the minds of the population. They continued to regard the hospital as a place that would shelter plague victims, not if but when another plague epidemic broke out. Following this reasoning, the regents commissioned decoration that would underscore the hospital’s primary function as a plague house. Drawing upon a rich history of iconography and moral philosophy, van der Schuer uses the disastrous effects of the plague to capture the essence of charity. In van der Schuer’s painting, the plague symbolizes human deprivation and the plague sufferer is a model of virtue. This way, the artist broadened the plague theme to make it relevant even when plague victims were absent.