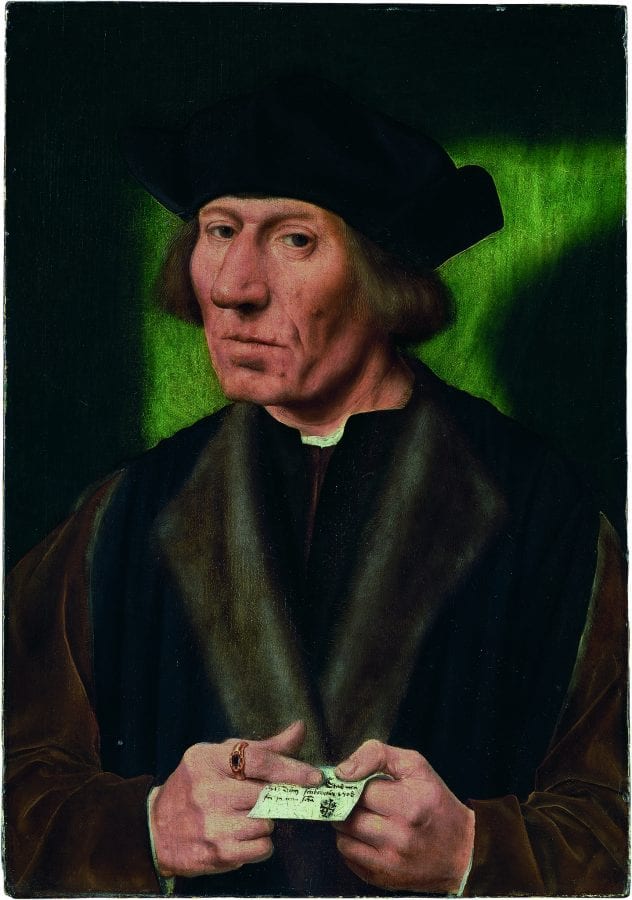

The major late fifteenth-century portrait of Jacob Obrecht, from the collection of the Kimbell Art Museum, has now been attributed as the earliest dated and, arguably, first signed work by Quinten Metsys that is known. The only contemporary surviving likeness of the renowned composer, the panel dates to the key first decade in Metsys’s career, a time when Hans Memling was the dominant model for the painter. This new attribution creates a benchmark for the artist’s oeuvre, against which other works can now be compared.

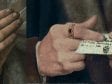

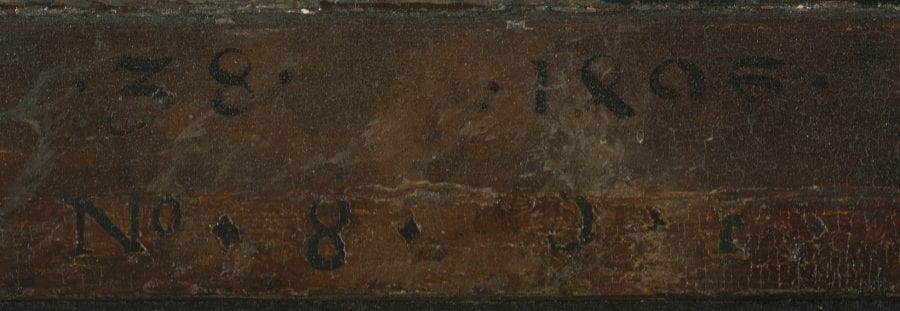

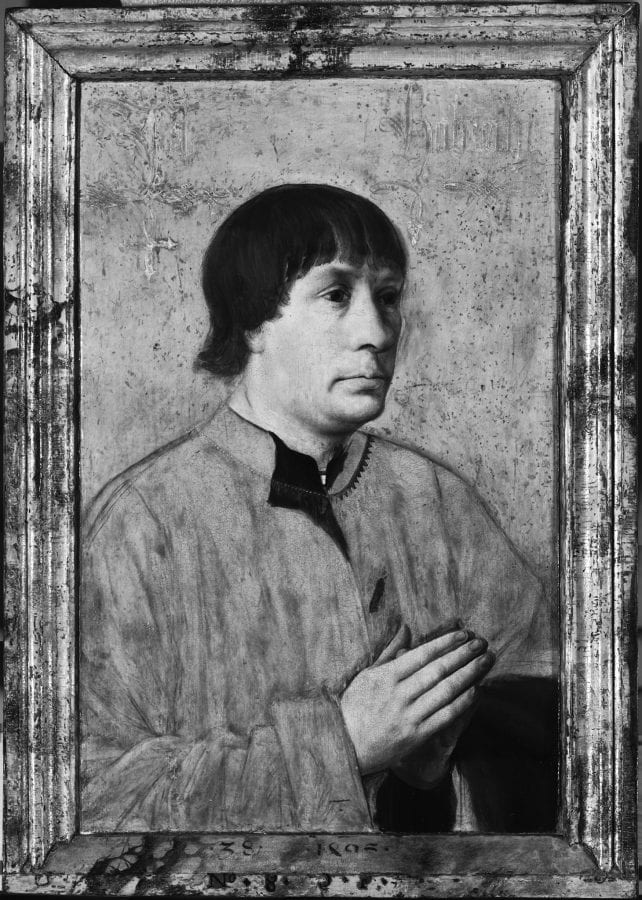

Hidden in plain sight, a major late fifteenth-century portrait can now be firmly attributed as the earliest dated picture by Antwerp painter Quinten Metsys (1466–1530). The authorship of Jacob Obrecht (fig. 1), long identified as a portrait from either the Netherlandish or French school, has perplexed scholars for over a quarter of a century, even before it entered the collection of the Kimbell Art Museum in the early 1990s.1 Recognizing the superb quality of the panel and the hand of an experienced master, the museum acquired this painting fully expecting to identify its artist someday. The painting is possibly the donor side of a devotional diptych, despite its large size, and would thus have faced a complementary panel of a religious subject.2 It is arguably the only surviving likeness of the renowned composer Jacob Obrecht, who was born in Ghent, son of the city trumpeter Willem Obrecht, and died of the plague in Ferrara in 1505.3 Inscribed Ja[cob] Hobrecht in illuminated Gothic script, the portrait is dated on its original, engaged, marbled frame with the year 1496 along with the number 38, the putative age of the sitter when depicted (fig. 2), thus placing the year of his birth to 1457 or 1458.4

Dirk de Vos ascribed Jacob Obrecht as a very late work by Hans Memling in his catalogue of the artist’s work in 1994.5 Memling primarily painted religious pictures on both the large and small scale, but as recent exhibitions in Bruges (1994) and New York (2005 touring) demonstrate, he also achieved innovations and a distinctive personal style in the practice of portrait painting, depicting sitters both before a monochrome background—like the Kimbell painting, whose lighter blue-green tone differs however from Memling’s black or dark backgrounds—as well as before summery, serene landscapes.6 More importantly, the Kimbell painting is dated authentically through original inscription to the year 1496, whereas Memling died in 1494.

Connecting Obrecht’s documented early time in Bruges—he worked in the city at St. Donatian’s as late as 1491—with local artist Memling, De Vos accounts for the fact that the panel is dated two years after Memling’s death by stating that it must have been left unfinished by the painter and finished in 1496 by another hand.7 De Vos based his attribution on “the exceptional quality of the work, its strong spatial character, the morphological detail of the facial features and the execution of the transparent surplice.”8 These very characteristics, however, can also be linked with the work of Metsys, whose dates plausibly suggest that he could have created the entire work in the stated year, 1496.

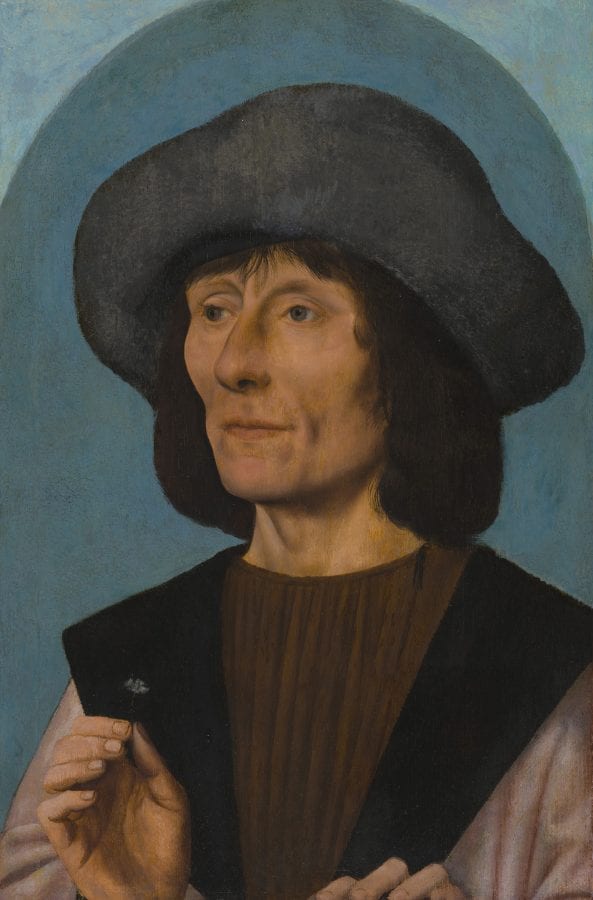

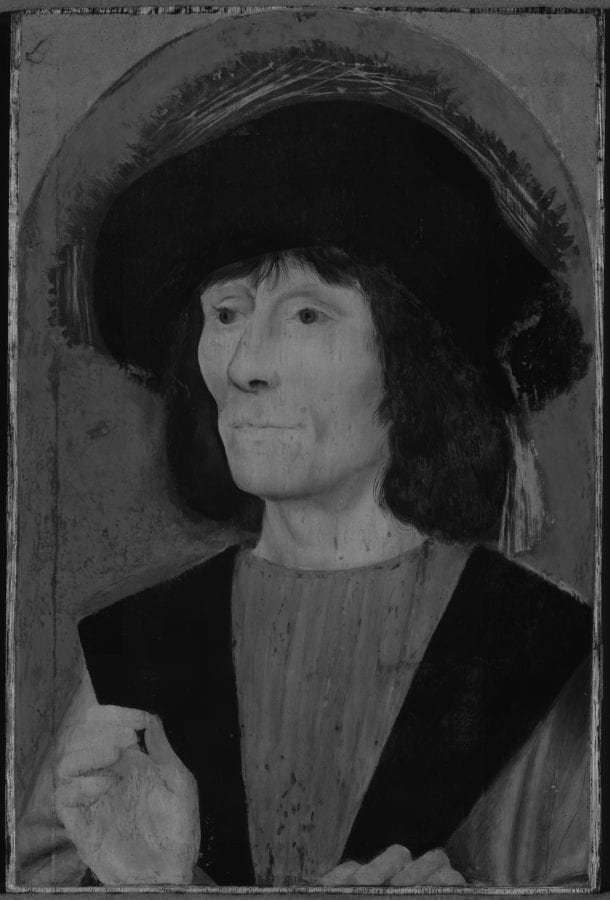

Lorne Campbell, Maryan W. Ainsworth, and Til-Holger Borchert expressed earlier doubts about the Kimbell panel’s attribution to Memling.9 Campbell noted that the work “seems to [have] be[en] painted in Antwerp” rather than in Bruges.10 Metsys overlapped with Obrecht in Antwerp during the precise time of the musician’s tenure at the Church of Our Lady in that city. In his early work, Metsys indeed looked to masters such as Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, and Memling.11 The latter was the dominant model for younger painters around the time of his death in 1494. Metsys later adopted the Memling portrait innovation of placing his sitters before a verdant summer landscape, as in the case of the Portrait of a Canon, ca. 1525–30, from the Princely Collections of Liechtenstein (fig. 3). Even Metsys’s earliest large-scale masterwork, his Saint Anne Altarpiece (1507–9; Brussels, Musées Royaux) still depends greatly in its central panel on Memling’s earlier sacra conversazione format, with holy figures situated within framed columns and before an atmospheric landscape background.12

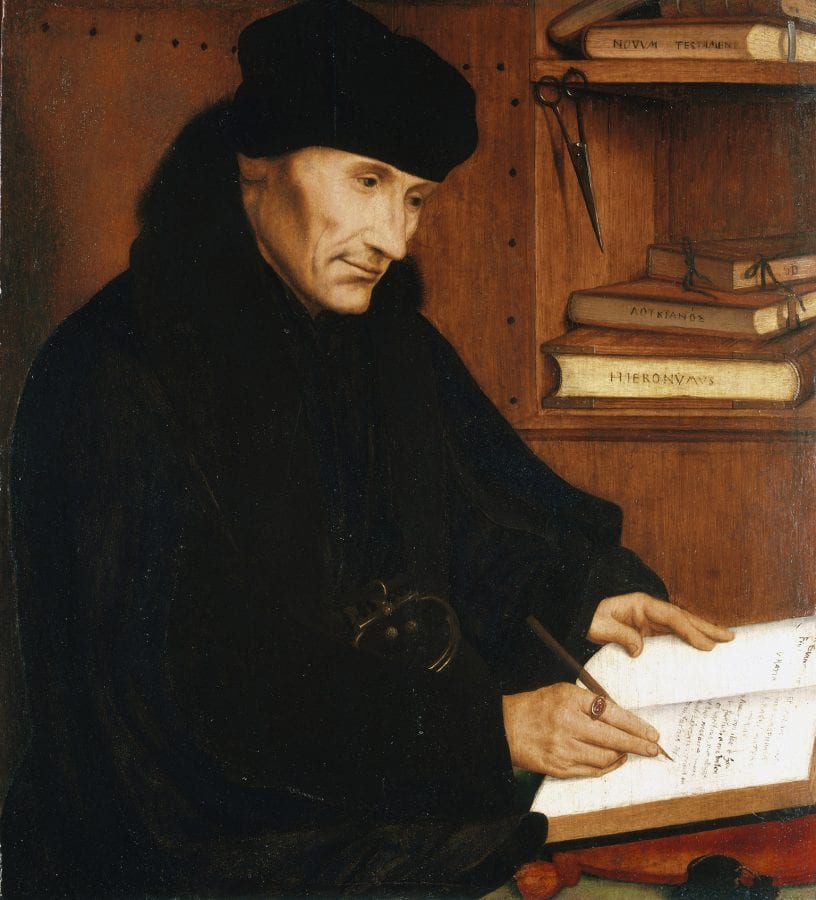

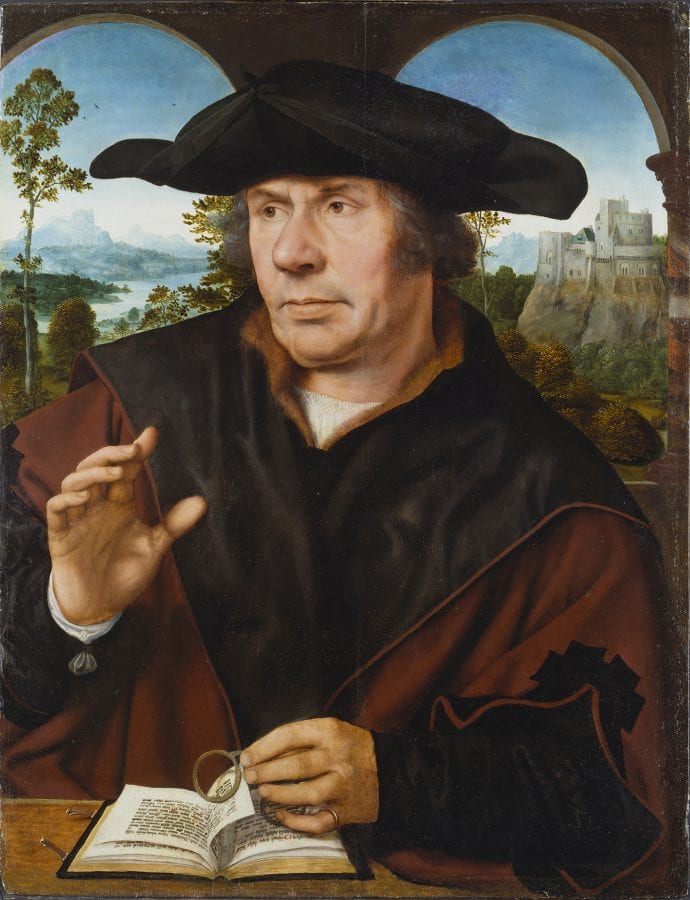

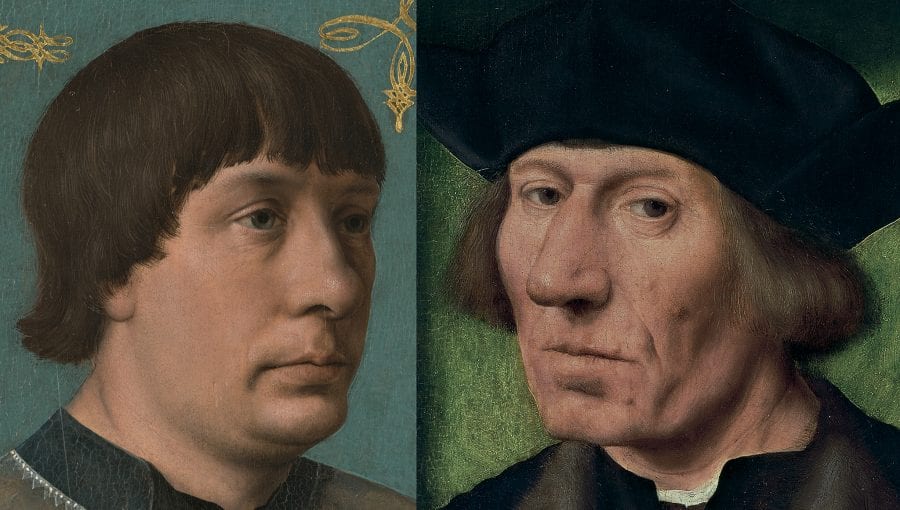

As exemplified in both the Kimbell and Liechtenstein pictures, Metsys’s own link with Memling is clear. Metsys’s use of dark outlining in creating his figures’ far profiles finds its precedent, for example, in Memling’s Portrait of a Man with a Letter in the Uffizi Gallery.13 Also notable is Metsys’s use of outlining in his modeling of hands, already found in Memling’s 1487 Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove (Bruges, Memling Museum).14 Concerning the Kimbell picture, De Vos does note that “a portrait this robust does not appear anywhere else in his [Memling’s] oeuvre, and no readily convincing points of comparison are available.”15 This robustness is evident, however, in other portraits by Metsys, most notably in his later Portrait of a Scholar (fig. 4).

About the presumed sitter, the internationally famous Flemish composer Jacob Obrecht, much is known. By the time Obrecht was in his early thirties, his compositions had already garnered such prestige that his masses and motets were being copied and played across the continent.16 In his list of the most talented musicians of the time, Johannes Tinctoris, the Renaissance era music theorist, mentions “Jacobus Obrechts” among them.17 Obrecht’s accomplishments were many. He became choirmaster at St. Gertrudiskerk in Bergen op Zoom, serving from 1480 to 1484, followed by a stint as master of the choirboys at Cambrai Cathedral.18 In October of 1485, he began serving as the succentor in Bruges at St. Donatian.19 While in Bruges in August of 1487, Obrecht received an invitation from Duke Ercole I d’Este to visit and perform at his court in Ferrara.20 In January of 1491 the composer received remission from his post in Bruges, and by June of 1492 he had been installed as the choirmaster of the Church of Our Lady in Antwerp.21 Here, presumably, Metsys, a member of the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke since 1491, depicted him in 1496.22 Obrecht would remain in this position until June or July of 1497, when he returned to Bergen op Zoom, followed by yet another tenure as the succentor at St. Donatian in Bruges in December of 1498.23 After a ten-month illness, Obrecht returned to the Church of Our Lady in Antwerp in June of 1501; there he would remain for two additional years.24

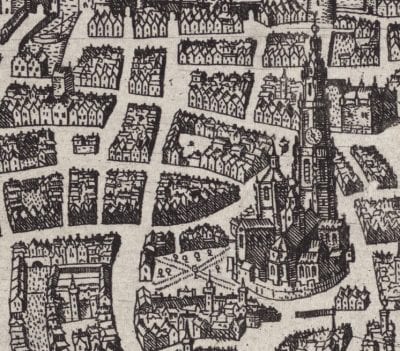

Antwerp at the end of the fifteenth century was fast becoming one of the most important economic centers in Europe.25 Thanks to this success and to capitalize on it, artists began flocking to the region starting in the 1430s. It is likely that most of them produced uncommissioned paintings, statuary, and tapestries for the nascent art market, and by the 1440s works were being purchased at the city’s art fairs and transported to as far away as the court of the Medici in Florence.26 Traveling to the city from places like Holland and nearby Bruges, artists brought with them the current style of painting popularized by Memling and Gerard David, creating a taste for their work both in the region and abroad.27 A distinctive Antwerp painting style would develop only in the new century.

Capitalizing on this economic success, the Church of Our Lady, at which Obrecht would later be employed, built in the 1460s “the first showroom in post-Classical Europe to be constructed expressly for the exhibition and sale of works of art.”28 The Onse Lieve Vrouwen Pand served as a venue in which artists could rent stalls to display and sell their wares (fig. 5). On November 13, 1481, an agreement was struck between the Church of Our Lady’s Pand and the Guilds of Saint Luke of both Antwerp (which Metsys would join in 1491) and Brussels, which stipulated that during the times of fairs all artworks in both cities would only be sold there.29

No one, from within or without the land of Brabant, [shall,] during the fairs of Antwerp, [sell] their altarpieces, panels, images, tabernacles, and carvings, polychromed or unpolychromed, of wood or stone, anywhere other than in Onser Liever Vrauwen [sic] Pand by the churchyard, [which] is occupied by the painters of Brussels and Antwerp.30

Economic historians Philipp Félix Rombouts and Théodore François Xavier van Lerius examined the historical records of Antwerp’s Guild of Saint Luke and other documents in the Cathedral Archives that record artists’ leasing of stalls in Our Lady’s Pand.31 They discovered a reference to “Quinten Massys (schilder)” taking on an apprentice named Ariaen in 1495, the year preceding the Kimbell picture, followed by a note stating: “Also this year our governors received a letter and a command from the fraternity of Onze Lieve Vrouwen, which was held in the Saint Luke chapel in the Onze Lieve Vrouwen church in Antwerp.”32 This evidence of a direct association between the members of the guild and the church itself, in addition to the proximity of the Pand to the church, make it probable that Obrecht, within his role as the choirmaster, would have been readily familiar with artists in the guild.

Both the year of the Kimbell picture as well as the prior year were remarkably fruitful for Obrecht at the Church of Our Lady. As choirmaster, in 1495 Obrecht received Bartholomaeus Martini, bishop of Segorbe in Spain and master of the papal chapel under Pope Alexander VI.33 To entertain such a prestigious guest would have been a high honor for the composer, a milestone in a lifetime of distinctions. According to the accounts of the Guild of Our Lady, a payment was made above his annual wage “to master Jacop the choirmaster, for entertaining the master of the chapel of the pope.”34 Then in 1495/6, Obrecht received both his annual salary and yet another additional payment, “for copying many motets.”35 With this influx of funds, Obrecht could have turned to any one of the artists of the Guild of Saint Luke, including Quinten Metsys, to commission a devotional work of which the Kimbell portrait panel may have formed a part. For any painter receiving such a portrait commission of a figure of his stature and position would itself have been a prestigious assignment and a mark of artistic merit.

Although records show that Metsys became a master in the Guild of Saint Luke as a painter in 1491, the first decade of his career has baffled scholars for centuries.36 His earliest biographers, seventeenth-century Antwerp enthusiasts Franchoys Fickaert and Alexander van Fornenbergh, make no mention of Metsys’s early works, focusing instead on the artistic origin myth that he was a self-taught artist.37 Modern scholars’ exhaustive research on the artist’s career still has left them unable to firmly attribute a single work to him before the early 1500s.38

The Kimbell’s panel, dated 1496, was created during this key time in Metsys’s early career, well before his known portraits and reliably identified religious images. With this attribution, therefore, the Obrecht portrait can now be considered the earliest known painting by the artist. The panel thus sheds light on Metsys’s formative years in Antwerp, before he had fully developed the signature style for which he was praised in later centuries as a founding painter in Antwerp’s artistic tradition.

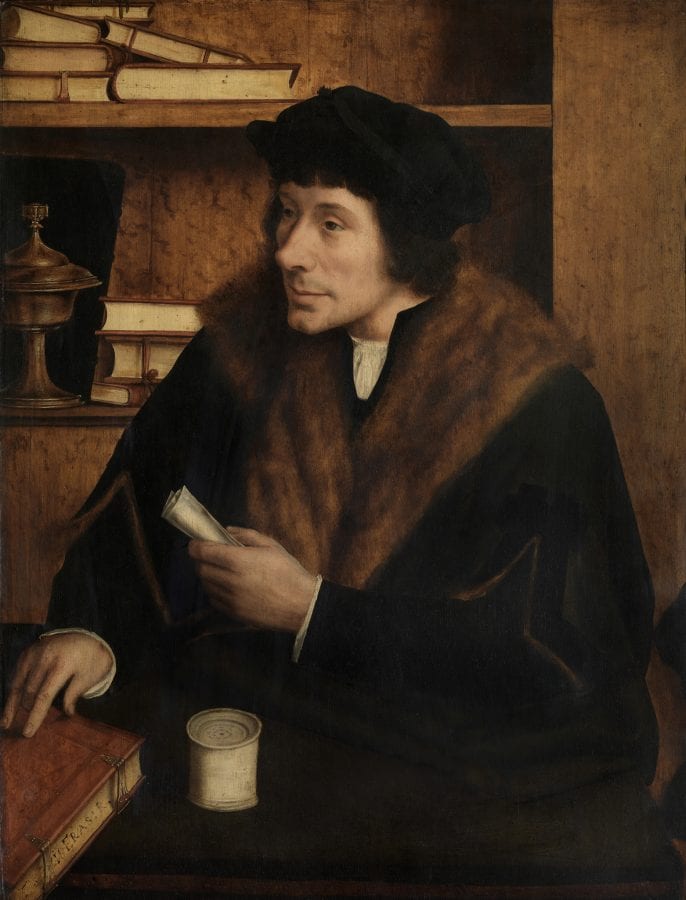

Like Hans Memling, Quinten Metsys was not a portrait specialist, instead focusing more on devotional compositions, but he did occasionally receive commissions for portraits, most famously painting the pendant likenesses of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Pieter Gillis in 1517, a gift for their mutual friend Thomas More (fig. 6 and fig. 7).39 A commission to depict the internationally prominent composer-musician Obrecht much earlier in the artist’s career would have held comparable prestige. Metsys approached each portrait afresh, creating a new paradigm each time. According to Max J. Friedlander,

Quentin [Metsys] developed no system of portraiture to which he clung, but rather treated each case on its own merits, according to the type of sitter who posed for him. His portraits are all different—in posture, composition, background and “props.” They may be square-topped or arched above, bust-length, with or without hands, or half-length. The background may be neutral or consist of a landscape, an interior, an architectural framework. The attitude may be tranquil or agitated. Every possibility is explored and nothing is ever repeated.40

In studying the variety of portraits attributed to Metsys, however, overarching similarities in paint handling and technique become clear, many of which are also quite evident in the Kimbell panel.

In 2016, the Kimbell’s Paintings Conservation department embarked on a joint technical and art-historical research project, utilizing infrared reflectography, X-radiography, and hyperspectral photography to determine which artist painted Jacob Obrecht. The initial association of the painting with the hand of Metsys was instigated by a visual comparison with his Vaduz Portrait of a Canon (see fig. 3).41 Besides the resemblance between the depiction of the canon’s translucent surplice and that of Obrecht, though admittedly the first is more painterly than the second, the paint handling used to depict the grayish-blue fur almuce that is draped over both sitters’ proper left arms is also strikingly similar. Examining the canon’s hands, most noticeably his proper right, which holds a pair of spectacles, one sees outlining and brushstrokes akin to the Kimbell painting (fig. 8). Though Obrecht’s hands are more carefully modeled than those of the sitter in the Canon and than those in other Metsys works, this extra detail can likely be attributed to the portrait’s early date within the artist’s oeuvre plus the extra care taken, given the prestigious nature of the commission. One also cannot help but notice that both Obrecht and the canon have the same distinctive curved and pointed thumbs, a Metsys trademark. The attention to surface rendering and minute details in both sitters’ visages are shared closely: facial hair, bangs, and even eyelashes (fig. 9). Careful facial contours, which create pronounced cheekbones that are further exaggerated with dark brown outlines, especially on the far side of the turned head, offer another familiar characteristic of Metsys’s works, further linking the paintings.

Closer in date to the Kimbell picture is Metsys’s 1509–12 Portrait of a Fifty-one-year-old Man, also referred to as Portrait of a Pilgrim, from the Oskar Reinhart Collection (fig. 10).42 This work, a somber depiction of the sitter after his completed pilgrimage to the Holy Land, similarly documents the date and age of the sitter, though here placed on a piece of paper held within his hands: “etas mea 51 dum scriberetur 1.5.0.9 / fui in terra sancta.”43 The well-dressed man, fully illuminated by a strong light, casts a dark shadow against a solid green background. Despite the fact that the gentleman is thirteen years older than Obrecht when Metsys portrayed him, the artist’s paint handling in representing these two sitters bears a remarkable structural similarity. A delicate blending of visible strokes creates a shadow play on the sitters’ faces, making them seem present in the viewer’s space as they gaze outward (fig. 11). For both figures, Metsys blocked in the general shape of their hair, using a shade of brown in one and a shade of gray in the other. Then, modeling from dark to light, the artist laid in lighter tones of similar colors before adding touches of black on top. While in Portrait of a Pilgrim these strokes span the length of the figure’s hair, in Jacob Obrecht they are abbreviated to only a few centimeters at the edge of the sitter’s hairline, crossing over onto his face. Similar abbreviated strokes can also be seen in Portrait of a Pilgrim along the edge of the gentleman’s fur-lined vest. These finishing touches, made using an aqueous black paint, are also used in an identical manner in the figures’ eyebrows and lashes, as well as in the highlighting of the wrinkles around their eyes. Beyond this technique, examination of both sitters’ lips and accompanying facial stubble also reveals a nearly identical treatment.

Due to the natural fading of pigments over time, Metsys’s careful contouring and adjustment of the facial profile in the Pilgrim have become more evident. These changes resemble those found in Obrecht’s profile, nose, and proper right shoulder—best seen using infrared reflectography (fig. 12). With an initially more pronounced silhouette, the delicate narrowing of Obrecht’s bone structure around his proper left brow and cheek and the raising of his shoulder turns the clergyman’s gaze to a greater degree toward its now-lost putative pendant image, bringing him closer to the viewer in the process. To the naked eye, a comparable subtle modeling can also be seen in the contouring of Obrecht’s skull, where refined straight lines gradually create the round form through built-up strokes.

Comparison of Metsys’s treatment of the pilgrim’s hands, which grasp the note bearing proof of his journey, with those of the choirmaster, Obrecht’s praying ones shows strong parallels in modeling and outlining (fig. 13). In both sets of hands, one sees the presence of the aforementioned “worked” brushwork, though to a lesser extent in the Reinhart picture. In the Pilgrim panel the same dark outlining of his fingers and fingernails can be observed. It is also important to note the sitter’s curved and pointed thumbs.

Although the Städel Museum’s Portrait of a Scholar (see fig. 4) is markedly more energetic and animated, a striking comparison can be made between it and Jacob Obrecht. As in the Kimbell panel, Metsys differentiated the figure of the Scholar from his surroundings and projected him into the viewer’s space with his use of dark outlining, especially evident in his right hand, which reaches out. The near identical subtle tonality and bravura paint handling in the flesh tones used to portray the lips, lower cheeks, chin, and plump jowels in both Obrecht and the Scholar capture not an ideal likeness, but, as De Vos notes, a “robust,” and reliable one (fig. 14). In both pictures, Metsys’s attention to details, such as the sitters’ stubble, unkempt eyebrows, and free-flowing hair, does not glorify these men as religious figures but instead shows them as accomplished men of the world, flattering them by depicting them as they are.44

Further examination of Jacob Obrecht, using infrared reflectography, reveals a section of underdrawing where Metsys loosely rendered the folds of the musician’s garments with both long and short hatched lines. Comparable lines can be seen in the underdrawing of the folds of the proper left side of the sitter’s jacket and sleeve in Portrait of a Man with a Pink (fig. 15), another early work by Metsys, the uncertain dating of which should now be reconsidered (fig. 16 and fig. 17).45 Infrared imaging also emphasizes the artist’s use of the aforementioned dark material, applied with the tip of a minute brush to create Obrecht’s delineated eyelashes and the strands of hair that rest on his face and along the profile of his head, which act as finishing touches.46

A similar use of this black aqueous paint can still be observed in some of Metsys’s late works, including the Prado Museum’s 1529 The Savior and The Virgin Mary (fig. 18 and fig. 19).47 Comparison of Christ’s and the Virgin’s eyes with those of Obrecht, both with the naked eye and with infrared reflectography, creates a compelling argument that the works are by the same hand (fig. 20 and fig. 21), albeit at different points in his career. It is also especially telling to note the treatment of both Obrecht’s and the Virgin’s hands. For all of Metsys’s prowess at depicting human anatomy, when portraying hands in prayer, the posterior hand in many of his religious works seems to fall short. The transition between both Obrecht’s and the Virgin’s proper left hands and their wrists is abrupt and lacks definition and modeling (fig. 22).

The most pronounced and noticeable change to the Kimbell panel, seen using infrared reflectography, is in the placement of the sitter’s hands (fig. 23). Metsys initially depicted Obrecht’s proper right thumb and index finger slightly higher. Between his reverently clasped hands, Obrecht originally held a small piece of paper that stuck out just enough to enable the artist to scrawl the year 1496 beside a pair of initials.48 The first of these initials is obscured; however, the second is unquestionably an M, implying the possibility that the artist may have intended to sign or at least initial the work in this small space.49

Examples exist of Quinten Metsys scrawling text upon pieces of paper in his compositions, including in the already discussed Reinhart Portrait of a Fifty-one-year-old Man. In his portrait of Pieter Gillis the sitter holds an inscribed piece of paper in his hand,50 while in the pendant portrait of Erasmus, Metsys identifies his sitter via references to texts produced by the Renaissance humanist, written upon the pages of the open book on which he works (see fig. 6).51 In the Louvre’s Moneylender and His Wife, the artist signed and dated the painting on a roll of parchment: “Quinten Matsys / Schilder 1514.” Metsys’s Portrait of a Man, in the Royal Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, is inscribed “anno 1527” on a folded piece of paper in the sitter’s proper right hand.52 Metsys also signed the Louvre’s Rattier Madonna and Child “Qn. M. [1]529.”53 Although the artist did not sign his full name on the Kimbell panel, most likely due to the small size of the piece of paper, the inclusion of only his initials is notable, since this work prefigures those later examples by ten to thirty years.

Two questions remain, however: why would Metsys have included this piece of paper in the Kimbell panel’s initial design, and why did it disappear in the final composition? As previously discussed, the opportunity to depict Jacob Obrecht at such an early time in the artist’s career would have been pivotal. Being commissioned to paint the likeness of such a prestigious international figure within Antwerp society not only would have garnered notoriety for the painter, but additionally would have provided a springboard for future portrait commissions. Including a reference to his own name, even a small one, would have made this opportunity all the more likely. As demonstrated by the previous examples, the artist typically included representations of paper in sitters’ hands or as additive details beside them, on which written information would be shown. In other portraits, Metsys’s subjects hold specific items, such as the hilt of a sword or a flower. In all these cases, the sitter’s hands are simply holding objects; none are shown in prayer. The inclusion of a piece of paper as part of Obrecht’s devotional gesture might have been considered improper and could therefore have been excluded from the final painting.

The portrait Jacob Obrecht by Quinten Metsys is now the earliest dated and, arguably, first signed work by the artist that is known. A pivotal work in Metsys’s oeuvre, the painting illustrates how he established himself as a portraitist of note, by depicting one of the most renowned composers of the time. The identification of this early work creates a new reference point in Metsys’s career, before the development of the individualized style for which he would receive wide repute. Using a formal language of painting akin to that of Hans Memling, Metsys simultaneously captured Obrecht’s individuality and the solemnity proper for someone in his position. This new attribution, alongside the scholarship of music historians, contributes to the ongoing reappraisal of the renowned composer in the context of his time and provides us with a more nuanced image of the man behind the music.