Three works by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) entail mythologized scenes of spontaneous generation, or the creation of species from nature’s raw matter: Head of Medusa (ca. 1613–1618), The Discovery of Erichthonius (ca. 1616), and the oil sketch Deucalion and Pyrrha (ca. 1636). In these works Rubens naturalizes the life of painting within its materials, implying matter—paint, with its pigments and mediating liquids—as an intrinsic, animating quality of his images and even as a counterpart to or collaborator with the artist. This essay explores these ideas to show how Rubens’s technical and artisanal understanding of painting and its materials could have informed his interpretation of ancient myths.

In his 1672 life of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), published in Rome, Giovanni Pietro Bellori inserts six lines of Latin verse that he says were inscribed on Rubens’s tomb in the church of Saint James in Antwerp and that conclude as follows:You, Rubens, give life and mind to your figures

And through you, light and shadow and color live.

What did death with its black funeral want with you, Rubens?

You live, the life you painted blushes with your color [Vivis, vita tuo picta colore rubet].1

The last line is a play on Rubens’s name, which is the present active participle of the Latin verb rubeo, to redden or blush.2 Turning the painter back into a verb, the epitaph implies that Rubens lives through his color and that his color lives through him. It also connects both Rubens and his color to the enlivening spirit of human blood, the circulation of which was first identified in the natural sciences of Rubens’s lifetime.3 The epitaph, however, was Bellori’s invention.4 Exemplifying what art historians have long recognized—that such biographies were forms of art criticism and art theory that responded to theoretical concepts visualized in early modern artworks—the imaginary epitaph makes it tempting to see, in Rubens’s often effusive uses of the color red, a kind of signature through which he encrypted an authorial presence in his works.5

This article traces a different idea in Rubens’s art, which is that color—paint, with its pigments and mediating liquids—also has a life of its own, a life painting cultivates at a material, elemental level. Indeed, although the epitaph might seem to imply that color achieves life only as a result of Rubens’s spirited actions (the furia del penello, or fury of the brush, with which Bellori elsewhere characterizes Rubens’s technique),6 it ultimately defines the relationship between Rubens and his color as chiasmic or dialectical. It thus emphasizes color itself an intrinsic, animating quality of Rubens’s images. This understanding of color as an animating force was formulated by Bellori’s Dutch contemporary Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678), whose Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst (Introduction to the Academy of Painting, 1678) described color as the “spirit and soul” (geest en ziele) of painting, comparing it to the fire stolen by Prometheus from the gods.7

A notion of paint as elemental or “vibrant” matter is communicated earlier in Rubens’s pictorial engagements with spontaneous generation.8 This was the belief, still current in the natural knowledge of Rubens’s time, that some life forms or species could be generated directly from decaying matter—birthed, as it were, by nature herself.9 Several mythological works by Rubens allude to spontaneous generation, three of which will be the focus here: Head of Medusa (ca. 1613–1618) (fig. 1), which depicts a menagerie of creatures being born from the gorgon’s blood; The Discovery of Erichthonius (ca. 1616) (fig. 2), whose subject is the monstrous offspring of Vulcan and Gaia, or Mother Earth; and the late oil sketch Deucalion and Pyrrha (ca. 1636) (fig. 3), whose theme is the postdiluvial regeneration of the human race from Gaia’s rocks, or “bones.” All made in Antwerp, these classicizing allegories of nature model intersections between natural and artistic creation. In this sense, they reflect ideas current in the early seventeenth-century Spanish Netherlands about the close relationship between artisanal knowledge and the knowledge of nature.

More than any other premodern scientific belief, spontaneous generation encapsulated the idea of natura naturans, or “nature naturing”—nature as a realm of constant flux.10 Seemingly dead matter, broken down and in decay, could mysteriously transmute into a new medium of life. The secret life of nature was a topic of fascination in the seventeenth-century Low Countries, where an atomistic view of matter arose alongside the earliest experiments in microscopy—the technology through which the theory of spontaneous generation would, by midcentury, begin to unravel. In the same period, ideas about nature were strongly shaped by the chemical and manipulative view of matter promoted in the writings and reception of the Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus (1493/4–1541). This body of texts often fashioned itself as a “secret” or occult discourse.11 As a paradigm for creation, however, spontaneous generation was distinctly ambivalent. Because it did not result in procreation, it bordered on the counternatural and raised anxieties similar to forms of pseudo-creation such as alchemy or the making of automata.12 Another such creative enterprise was oil painting, whose techniques were analogized with those of alchemy.13 Were paintings truly alive, or were they objects and commodities made of dead matter—natura naturata? If life could arise from dead matter, could the painter’s colors, composed of broken-down nature, similarly contain a generative impulse? At what material level and through what techniques could the life of color be cultivated? Rubens’s pictured myths of spontaneous generation are an important source for his thinking about such questions. Conceiving of paint as a modality of nature, each centers on a generative substance identified with nature’s bodily matter.

Studies of art and technology in the early modern Low Countries by Christine Göttler, Karin Leonhard, Sven Dupré, and others have shown the intersections between the “meaning of matter” in early sciences and in artisanal worlds, including those of oil painting.14 Recent scholarship has further shown that Rubens’s theoretical understanding of painting was closely related to his pursuit of natural knowledge, including an interest in Paracelsan concepts of matter.15 Indeed, as Teresa Esposito has argued, “the study of nature imbued by current scientific discourse constituted an essential and intrinsic factor within [Rubens’s] art theory.”16 Building on this historiography, this essay focuses on Rubens’s mythologized scenes of spontaneous generation as a case study for how his artisanal consciousness, informed by ideas about nature’s creativity, found expression in his images themselves.

“Discovering” Color in Nature

Before turning to Rubens’s depictions of spontaneous generation, I want to consider a late oil sketch in which he depicts the “discovery” of an artisanal dye (fig. 4). Created around 1636 as a preparatory model for the massive pictorial cycle Rubens designed for the Torre de la Parada (a former Spanish royal hunting lodge near Madrid),17 it illustrates a legend first recounted in Julius Pollux’s Onomasticon, a second-century Greek thesaurus.18 One day, Hercules was walking along the shores of Tyre (present-day Lebanon), on his way to see a nymph he loved. A dog walking alongside him found a mollusk in the sand, bit into it, and stained its muzzle with the creature’s ink. When the nymph saw the stain on the dog’s fur, she was struck by its beautiful color, sparking a local industry for Tyrian purple. Extracted from the secretions of predatory sea snails, purpura was the most precious dye of antiquity, reserved by Roman sumptuary law for imperial dress.19 Classical sources often identify purpura as a deep and precious red, the same color Rubens uses to depict the legendary stain.20

Rubens would likely have understood Tyrian purple as not just any color, but color par excellence. It illustrates perfectly color’s ability to transcend its material basis as it moves from nature to culture, from mollusk’s blood to a signifier of imperial splendor. Rubens was deeply familiar with such signs of splendor and pomp; he trafficked in them. Yet here he divests from them, reifying color itself and taking us back to nature, to the mollusk and its marvelous secretion. Despite the Latin etymology of Rubens’s name, what is most striking about the sketch is not its emphasis on his “signature color,” but on that color’s basis in living nature. Collapsing the materials of nature and art, it depicts a moment when color occupies a liminal space and subtly identifies the painter with that boundary.

The sketch has received relatively little attention in the vast Rubens scholarship, with Svetlana Alpers even admitting to some puzzlement as to why Rubens chose to include the strange scene in the Torre de la Parada cycle.21 Only one earlier depiction of the legend is known, in the background of an image of Hercules and Io in the studiolo of Francesco I in the Palazzo Vecchio.22 That the erudite Rubens, faced with the task of designing more than one hundred pictures for a hunting lodge, would have chosen an arcane legend featuring a ravenous dog was hardly out of character. Scenes of Hercules in his “downtime” were a Renaissance genre exemplified by the themes of Drunken Hercules and Hercules and Omphale, both of which Rubens had painted earlier in his career, and which thematized Hercules’s emasculation in a carnivalesque reversal of his heroic masculinity.23 Here, though, rather than milking such antiheroic tropes, Rubens depicts Hercules in a rather quotidian guise, patting a dog’s head and kneeling on a beach in the moment of “discovering” a color. The sketch emphasizes the sensory environment of discovery: the feeling of fur on skin or warm water lapping on sand; the sight and perhaps sound of a bird flying overhead.

The legend encases a history of how and where Tyrian purple was actually produced in antiquity. Yet as Julius Held has argued, Rubens’s image may also have referred to a more recent development in the history of color: the discovery in 1630 by the Dutch alchemist, inventor, and engraver Cornelis Drebbel (1572–1633) of how to dye wool a deep red using a solution of cochineal and tin.24 Like the discovery of Tyrian purple, this was said to have happened by accident, when Drebbel dropped a flask of aqua regia, a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, onto a tin windowsill.25 The parallel is strengthened by Rubens’s identification of purpura with the color red. As Aneta Georgievska-Shine and Larry Silver have pointed out, the image may therefore also have implied an analogy between ancient Phoenicia and Spain, which had, since the 1520s, been extracting and exporting cochineal red dyes, made from insects, from its colonies in Central America.26 Such an interpretation is supported by a canvas painted after Rubens’s sketch by Theodoor van Thulden (1606–1669) (fig. 5).27 In this larger version, the shells on the beach acquire more variety and specificity, like precious marvels washed ashore. The cooler and darker tones draw attention to the horizon, where ships recede in the sunlit distance or gather in the crowded harbor. The imagery of travel, “discovery,” and collecting resonates with the scene’s earlier appearance in the studiolo of Francis I, in which the central ceiling fresco, celebrating the Medici natural collections, depicts Prometheus receiving jewels from nature.

Two things are worth keeping in mind. First, antiquity could function as an imaginary geography onto which Rubens mapped contemporary concerns, including ones related to the mercantile nexus of the Spanish Low Countries. Second, colors were commodities that, having been extracted from nature—from insects, minerals, stones, clay, berries, tree roots, wood, fossils, bones, and other raw materials—could be understood not only as traces of nature but also as evidence of nature’s quasi-artistic impulses.28 Modified and transported to new geographies, color became the foundation of further transformations—liquefying, mixing, layering, flowing, scumbling, drying—that evoked nature’s own metamorphoses. Such technical and material elisions between nature and painting are the subjects of Rubens’s myths of spontaneous generation.

The Bloody Cornucopia: Head of Medusa (ca. 1613–1618)

Re-naturalizing color in nature’s hidden vessels, Hercules Discovering Tyrian Purple evokes an earlier, better known work by Rubens, Head of Medusa (fig. 1a), painted in Antwerp around 1613–1618 in collaboration with Frans Snyders (1579–1657).29 Two versions of this work exist today: a canvas held in the Kunsthistorisches Museum and originally owned by George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham (1592–1628); and a panel held in the Moravská Galerie in Brno, whose first owner was most likely the Amsterdam merchant Nicolas Sohier (1588–1642).30 Aside from their different surface supports, the two versions are virtually identical.

In each, we see the gorgon’s head lying on a precipice of jagged rock. A white shroud or veil wraps around her head, mingling with strands of her hair. Blood gushes from her neck and also seeps from her eyes, nostrils, and mouth. Around the head, snakes, knotted into a complex arrangement, writhe and shimmer in a variety of green, yellow, and coppery brown hues. We seem to be encountering the Medusa at night, in a dark recess brightly and unnaturally lit for our inspection. The tenebristic lighting dramatizes the snakes’ movements; light flashes and disappears at intervals, visually animating them. The head’s prone position and pale skin make it seem as if the gorgon is both recoiling and hardening—being petrified, in both senses of the word. The right eyelid is peeled back, revealing a bulging eye whose white gleams like mother-of-pearl, reverberating with a glint of white impasto. Surrounding this sculpture-in-progress are signs of wild, fast-growing nature: a patch of ivy that springs up from the foreground, ferns and vines crawling up the hillside, and, in the upper left corner, a distant forest stippled in beneath a cloudy nocturnal sky.

Baby snakes appear in the wound of the Medusa’s neck, a tangle of gore from which a few drops of blood appear to separate themselves, pulsing forward on the precipice. In the Pharsalia (ca. 61 AD), the Roman epic poet Lucan had claimed that when Perseus was flying over Africa with the gorgon’s head, drops of her blood spilled to earth and mingled with the soil, generating all of the snakes of Libya.31 The Medusa’s blood was said by Ovid to have created coral, a story often represented or alluded to in early modern images.32 However, Rubens and Snyders are the only artists known to have made the Medusa’s generation of snakes the principal subject of an image, conflating the gorgon’s death scene with this grotesque birthing scene. Their decision to emphasize the myth’s zoological aspect may have been informed by their collaborative process: Snyders, a specialist in the naturalistic depiction of animals, may have been pleased with this novel and dramatic framing of his craft.33 In addition to the snakes, the gorgon’s blood appears to have spawned an entire menagerie—two spiders, a scorpion, a yellow and black salamander that glances up at us, and a golden snake with two heads—presented on a rustic version of the type of shelves that structured collectors’ cabinets.34 Emphasized by its positioning directly below the Medusa’s right eye, the two-headed snake, known as an amphisbaena, was a topic of discourse in early seventeenth-century natural history. Although fantastical, it had been catalogued by Pliny and by sixteenth-century natural historians such as Conrad Gessner (1516–1565), who believed it to be a real species—a kind of natural monster.35 A specimen had allegedly been discovered in Mexico in 1609, and images of the “Mexican amphisbaena” were disseminated at the Accademia dei Lincei in Rome.36 A 1617 painting of a collector’s cabinet by Frans Francken the Younger (1581–1642) depicts, among other curiosities, a framed painted study of an amphisbaena that is identical to Snyders’s creature (fig. 6) and may reflect a shared and now lost source.37

Such details starkly differentiate the work from a close predecessor, the Head of Medusa by Caravaggio (1571–1610).38 Painted in 1597 on a convex wooden rotella, or round panel crafted to resemble a shield, the version of Caravaggio’s work held today in the Uffizi was originally displayed in the hand of a life-size tournament doll in the Medici armory. It was thus understood by early viewers as an apotropaion, a protective image able to turn its owner’s enemies to stone.39 Rubens and Snyders’s Head of Medusa has, similarly, been connected to neo-Stoic philosophical notions, much discussed in Rubens’s intellectual circle, about the power of images to both move and immobilize their viewers.40 The Amsterdam collector Nicolas Sohier, who owned a version of Rubens and Snyders’s Medusa, apparently kept it behind a curtain and unveiled or unleashed it on selected viewers to heighten its effect—an act perhaps alluded to or “doubled” in the veil wrapped over the Medusa’s hairline.41 Viewers of the painting would have been prompted in an exercise of overcoming their initial terror—which mirrored the Medusa’s own pathos at the moment of her death—to reach a state of neo-Stoic apatheia, in which a person is unmoved by the emotions or “passions.”42

This explanation of how the painting constructed its viewers’ responses does not, however, fully explain the decision to depict the Medusa’s creative acts, refashioning her as an allegory of nature and identifying her blood as an actor, or author.43 The excessive blood might have made the image more horrifying, but the Medusa’s prone position, a guise that is distinctly more objectified than in Caravaggio’s image,44 also invites a deeper inspection of nature at work.

Marvelous Matter

Significantly, Rubens and Snyders’s emphasis on spontaneous generation appears to have been generative for other artists, directly or indirectly inspiring an entire subgenre of baroque painting known as the sottobosco or forest-floor still life.45 Most closely associated with the work of the Dutch painter Otto Marseus van Schrieck (1613–1678), this image type offered viewers a glimpse into the mossy, steamy, creatural worlds of the undergrowth—the cycles of creation and decay unfolding just above the earth’s surface and in nature’s hidden recesses (fig. 7).46 As Karin Leonhard has argued, such works fashioned painting as a form of “negative mimesis” akin to spontaneous generation. They therefore offered an alternative to the widespread comparisons between image-making and sexual reproduction.47 If the latter drew from the Aristotelian dichotomy of feminine matter and masculine formative spirit, the sottoboschi destabilize this binary by depicting nature atomized into its tiniest particles, revealing the formative impulse within nature’s own bodily matter. As Leonhard points out, painters in this genre often employed forms of nature printing, using actual clumps of moss or mushroom spores to print images of the same or embedding real butterfly or moth wings in the painted surface. The maker of such works is conceived not as an Apollonian hero who infuses matter with life, but rather as an artisan who collaborates and cross-fertilizes with nature at an elemental level.48

The sottobosco genre can, in turn, make us think differently about Rubens and Snyders’s painting. We might look again, for instance, at the distant forest whose spongy texture evokes, if not indexes, the use of a natural matrix (fig. 8). The still-life elements may further allude to another type of technical elision between art and nature: life casting. Collectors’ cabinets often included metal life casts of reptiles among other types of preserved specimens. The making of such objects entailed molding a freshly killed animal in plaster then replacing it with molten metal, transforming it into a work of art shaped by nature herself.49 As Susan Koslow has pointed out, Snyders may well have studied bronze casts of snakes to master the intricacies of snakeskin for Head of Medusa.50 Not only does the gorgon’s head resemble a stone sculpture, but some of the creatures on the precipice—in particular, the amphisbaena and the peculiar coiled reddish-brown snake on the left—appear oddly static, like specimens or, indeed, metal casts. In the final act, then, some of Snyders’s creations take their places back where they began, as artificialia displayed on a shelf. At the same time, the amphisbaena’s shimmering golden skin and the orgiastic movements of the snakes surrounding the gorgon’s head suggest a reanimation of the dead models in full, living color.

Recent studies have shed light on Rubens’s reception of the Paracelsan alchemical tradition, an aspect of his theory and practice of painting that earlier scholarship had largely overlooked.51 Three extant copies of a lost portrait of Paracelsus by Quentin Metsys (1466–1530) are attributed to Rubens or his students. They depict the physician and alchemist holding a book open to the word Quintisense, a pun on Metsys’s name that refers to “the alchemical quinta essentia,” or fifth element (ether).52 Moreover, a transcription of Rubens’s lost theoretical notebook, most likely made by his student Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), contains a recipe for life casting flowers and animals in metal, a technique whose alchemical associations have been explored in depth by Pamela Smith.53 Most significantly, Rubens’s tract on the human figure, published in Paris in 1773 and one of a handful of essays from the lost theoretical notebook, appears to have contained references to Paracelsan theories about the macrocosmic nature of the human body, including an illustration of three shapes (a square, a triangle, and a circle) that, in Paracelsan alchemy, corresponded to the tria prima, or three primary chemical elements: salt, sulfur, and mercury.54

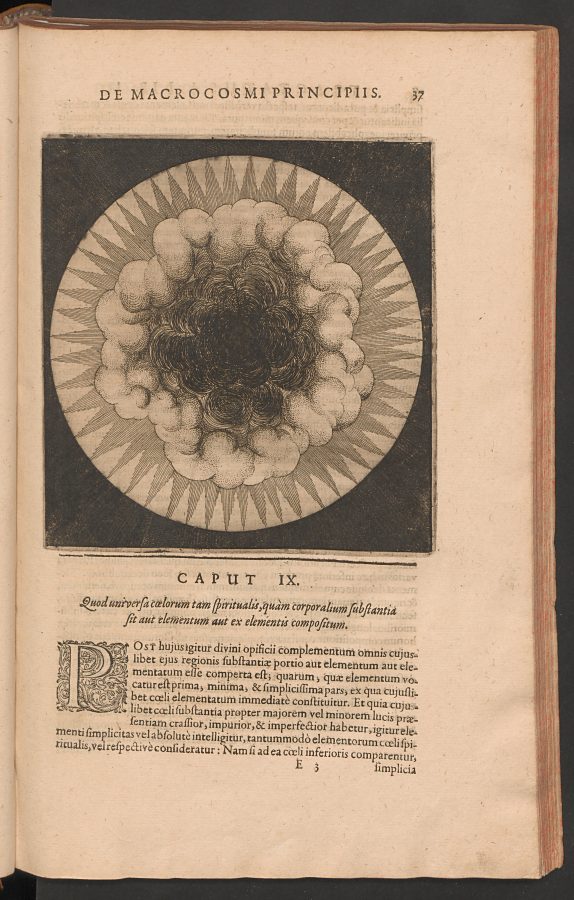

In Head of Medusa, nature’s finished works are displayed alongside the petrified symbol of nature: the gorgon’s head with its deathly, marmoreal coloring. Both are juxtaposed with that which can never be collected or displayed: nature naturing or matter mattering. An amorphous substance both prior and subsequent to the feats of verisimilitude that surround it, the blood is exposed to the viewer only through a violent rupture that reverses creation. In this sense, it evokes the primordial states of matter described in natural philosophical texts. The materia prima or “prime matter,” in which the four classical elements (earth, water, air, and fire) were thought to be still mixed together, and the mysterious processes through which this substance evolved into creation and its numberless forms, were the subject of widespread fascination around 1600.55 Some artists even made elaborate attempts to represent it. Among the many illustrations for the Utriusque cosmi (1617) of Robert Fludd, an English Paracelsan physician and philosopher whom Rubens may have known,56 is an etching that visualizes the earliest phase of the separation of the elements (fig. 9).57 Similarly, an engraving, created in 1589 by Jan Muller (1571–1628) after Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) as the title page to the pair’s Creation of the World series, depicts the sphere of creation pulsing with elemental chaos (fig. 10).58 Like such beautifully inscribed clouds or globes, the Medusa’s blood gives artistic form to formless matter that seems to pulse with the potential for images; it distills this enlivened matter into tiny droplets, identifying it with color, rather than line. This is achieved by adding small flecks of white and black on either side of each red drop, indicating the separation of lightness from darkness that initiates all creation (fig. 11). To borrow language from the art historian and philosopher George Didi-Huberman, this non-objective, material wonder is “the very symptom of painting—the materiality of painting, that is, color,”59 represented here by the color red and its mysterious fluctuations between matter and form.

Technical studies underway at the University of Antwerp may soon determine the actual material basis for the Medusa’s blood.60 However, whatever the pigment used, the blood may well have alluded, like the bloody stain in The Discovery of Tyrian Purple, to cochineal, the precious red dye obtained from the female specimens of parasitic cactus beetles in Mexico. Transported, like the gorgon’s blood, across continents, cochineal was one of the most valuable and heavily traded commodities of the Atlantic world, typically used by European painters only sparingly as an intensifying glaze layered over other reds.61 Situating the gorgon’s head on a mountain precipice that recedes into a vast distance, the painting may further represent Mount Atlas—another of the gorgon’s creations, which was associated with the Magreb mountain range in Northern Africa. It therefore evokes the myth’s wide geographical range, which through the amphisbaena now includes not only northern Africa but also Mexico. Though Perseus is absent, he is implied both as the ideal princely viewer and as the traveling hero who flew around the world carrying his marvelous prize: the head of Medusa and her blood.

Another red colorant the blood might have invoked was vermilion, a pigment with a history of local production in Antwerp.62 Derived in antiquity from cinnabar, a byproduct of mercury mining, vermilion had been produced synthetically in Europe since the Middle Ages by mixing mercury and sulfur to form a black mercury sulfide. When heated in a retort, this compound vaporizes and recondenses in red crystals that can then be extracted and ground up to produce the pigment.63 Yet as Cennino Cennini had already remarked in his Libro dell’Arte (ca. 1400), vermilion was unstable and had a tendency to darken over time, reverting to its original blackness.64 Because of this instability and oscillations between red and black, which mirrored and likely informed descriptions of alchemical transmutation, vermilion was strongly associated with alchemy, a “meaning of matter” that Head of Medusa’s generative imagery exploits.65

Joachim von Sandrart (1606–1688) claimed that when an alchemist once visited Rubens, inviting him to fund his experiments, Rubens replied that he had already “found the true philosopher’s stone in [his] brushes and colors.”66 Emphasizing painting’s life-giving potential, the anecdote is also a wry statement about Rubens’s commercial success and how “brushes and colors” reside at the crossroads of unstable and fluctuating material values. A center of the maritime trade in luxury commodities, Antwerp had developed a vibrant artisanal culture by the first half of the sixteenth century. Its practitioners responded to the city’s “feverish capitalistic boom”67 by intensively navigating their own role in transforming nature through artifice and in manipulating materials.68 By the early seventeenth century, when Antwerp’s mercantile economy was in steep decline due to the war between Spain and the rebellious Northern Provinces, such manipulations, particularly those of oil painting, took on an outsized meaning in Antwerp’s visual culture. Painters in Rubens’s circle frequently analogized their artistry both with alchemy and with the actual production of currency (for instance, in depictions of Vulcan’s forge), emphasizing the fundamental instability of the material world and the value of artisanal knowledge.69 Presenting the gorgon’s blood in flux, Head of Medusa epitomizes a cultural understanding of color as “mercurial” in the deepest sense—both mutable and transformative, subject to manipulations and the agent of such manipulations.

Generative Wounds

The gorgon’s blood is also an authorial interstice, a space between hands. It is not immediately clear who would have painted it, Rubens or Snyders. However, technical studies of early seventeenth-century Flemish collaborative paintings show that the figure painter typically executed his work first, leaving a reserve space for his collaborator to fill in later.70 Here, then, Rubens’s overflow, the substance that erupts from his own “still life” of the petrifying head, becomes the raw material for Snyders’s still life as well. The painters are implied as co-sanguine in their work.

The emphasis on a regenerative wound resonates with another Rubens-Snyders collaboration of this period, Prometheus Bound (ca. 1616) (fig. 12).71 As Elizabeth Honig has shown, such Flemish collaborative paintings were aimed at an audience of savvy amateur collectors, or liefhebbers, who could take pleasure in recognizing the various hands at work.72 Both Head of Medusa and Prometheus Bound reflect this competitive and self-conscious artisanal culture in which painters marketed and mythologized their skills and, as argued here, their materials.73 Depicting their protagonists in vertiginous rocky settings, and divided with a striking evenness between figure and still life, both paintings demonstrate Rubens’s ability to depict extreme ontological and emotional states, as well as Snyders’s mastery of the complex textures of feathers and scales.

Both also feature mythological protagonists deeply associated with the visual arts. According to the version of his myth attributed to Aeschylus, Prometheus was the archetypal human creator in competition with the gods whose theft of fire from Mount Olympus was the foundation of human technology, culture, and the arts.74 The Renaissance authors Pomponius Gauricus (De Scultura, 1504) and Natalis Comes (Mythologiae, 1567) identified Prometheus specifically as a sculptor.75 The Medusa, in turn, was both a victim of metamorphosis (her hair transformed by the angry Minerva into snakes) and an agent of it, able to petrify living bodies with her gaze and to create new species with her blood. As Caroline van Eck has argued, her myth therefore “offers among the most versatile and ambivalent paradigms of the emergence of figuration or ikonopoesis—literally the making of images of living things—both in sculpture and in painting.”76

Rubens depicts Prometheus chained upside-down to the mountainside while an eagle pecks out his liver, a punishment that—according to some versions of the myth—was repeated endlessly, since the liver grew back each day.77 An ekphrasis on the painting by the Dutch poet Dominicus Baudius (1561–1613), sent to Rubens in a letter of 1612, describes how Snyders’s creature seems to “beat the air with its wings” and “eject savage flames” from its eyes.78 It is as if Snyders picked up the torch depicted in the lower left corner and enlivened his work with the fire Prometheus stole, claiming the torch specifically for painting, rather than sculpture. Baudius’s poem also links the fire to Prometheus’s exposed blood: “Blood oozes from the chest of Prometheus and colors every spot where he treads his claws. The piercing eyes eject savage flames.”79 The eyes of Snyders’s eagle indeed blaze fiery red (fig. 13). Baudius’s text, and the visual cues to which it responds, anticipate Hoogstraten’s later comparison of the Olympian fire to color, an instance of a Flemish collaborative painting anticipating rather than reflecting written art-theoretical discourse.80

Once more, Rubens concentrates this pictorial enlivenment, the fiery “geest en ziele” of painting, in a wound (fig. 14). Like the gorgon’s blood in Head of Medusa, Prometheus’s liver is situated at the image’s compositional and narrative center. These works thus dramatize painterly collaboration in the form of a violent clash, inviting their viewers to make a chain of competitive comparisons: between figure and still life, sculpture and painting, and creative powers human, natural, and divine.81 Both paintings construct intricate representations around exposed sites of regenerative bodily matter that appear physically internal to the images themselves. In this way, they implicitly naturalize the life of painting within its materials, characterizing matter as an active agent in artistic creation and as an analogue of, rather than an opposite to, the artist.

Living Liquids: The Discovery of Erichthonius (ca. 1616)

The Discovery of Erichthonius (ca. 1616) is among Rubens’s strangest mythological scenes (fig. 2a).82 Like Head of Medusa, it depicts Mother Nature in a polarized form, as both a female sculptural body and the generative liquid that erupts from it. According to Ovid, when Vulcan tried and failed to rape Minerva, his seed spilled onto the earth, accidentally mating with the mythological Earth Mother, Gaia. Their offspring was Erichthonius, a human infant with serpentine lower limbs. After his birth, Minerva shut him in a box, which she gave to the three daughters of the Attic king Cecrops, warning them never to look inside. Rubens depicts the moment when one of the girls, Aglaurus, disobeys, revealing the monster to her sisters.83 The scene is set in an ornate Flemish garden filled with antiquarian objects, the largest and most prominent of which is a mossy stone fountain statue of Diana Ephesus, an ancient herm that in the Renaissance had become an emblem of nature’s fertility.84

This odd tale of spontaneous and monstrous generation was rarely depicted in the early modern period outside of illustrated Ovids.85 However, several versions of Rubens’s depiction of the scene survive, including a preliminary oil sketch at the Courtauld (fig. 15), at least two highly finished modelli, a finished canvas painting, and a print made after Rubens’s design by Pieter van Sompel (ca. 1600–1643).86 Svetlana Alpers has interpreted Rubens’s image as a classicizing “allegory of the fertility and diversity of nature.”87 In the Courtauld sketch, the Ephesian fountain takes up much of the extant surface. Sixteenth-century emblems identify Diana Ephesus simply as Natura, an association that also extended to Gaia, or Mother Earth.88 Erichthonius’s mother is therefore present at the scene in sculptural form. In all extant iterations of Rubens’s image, the statue appears to be as vivacious as the “living” figures, even if its grisaille coloring also cordons it off as a symbolic, unnatural body. Its eyes roll upward, conveying both a grotesque ecstasy and a certain ontological ambivalence befitting a statue. The gray coloring of Erichthonius’s serpentine legs seems to confirm a kinship with the statue; as he does in Head of Medusa, Rubens asserts a bizarre affinity between a petrified female body and her serpentine creation. In the large canvas painting, the scene expands to include a boy, an old woman grinning satirically at the viewer, and a landscape with gridded planting beds. The grotto containing the fountain is encrusted with a variety of glossy shells and a red coral branch, and further decorative objects appear in the garden, including a herm of Pan and a vase ornamented with a winged head of Medusa (gorgoneion). In this garden, Nature is represented either by her specimens or in the various symbolic forms given to her by artists. She is natura naturata, “nature natured.” One exception, however, merits consideration.

The fountain’s wide basin cuts off Diana at the waist, beneath which a silvery cascade of water flows. Water also streams from Diana’s breasts and from the open mouths of the carved dolphins at her sides. Rubens’s depiction of the Ephesian herm as a fountain statue in a grotto may have been inspired by examples he had seen in Italy.89 It also enables him to identify a sculptural fragment as the maternal source of the “real,” living, flowing world. Seen also in Head of Medusa, the Rubensian topos of the liquefying statue visualizes theoretical ideas found in another section of the lost theoretical notebook, De imitatione statuarum.90 In this text, Rubens encourages painters to study and make copies after ancient statues, which captured the human body in the perfect form it had achieved in antiquity.91 The goal of this copying was not imitation, however, but absorption and reanimation. According to Rubens, in order to wrest the living figures from the hard material in which they had been calcified, painters should “be imbibed” with ancient statues (imo imbibitionem),92 a process implying liquefaction or even transmutation. Rubens’s scenes of spontaneous generation reflect this theoretical association of painting with mutable, liquid matter that sparks life. In The Discovery of Erichthonius, Gaia, personified in ancient stone, is reanimated by water that sets her generative processes once more into motion. Like the gorgon’s blood, the water that flows from the statue construes painting as tapping into a vital wellspring, and the painter as someone who transacts in nature’s hidden creative energies.93 A century earlier, Lorenzo Lotto (ca. 1480–1566/7) had portrayed the antiquarian merchant Andrea Odoni holding a statuette of Diana Ephesus, an emblem of the mysteries of nature and antiquity alike (Windsor Castle, 1527). Rubens elides the two: brimming with water, his Ephesian herm once more becomes a living source. The moss on the basin and the vines that crawl around the shells confirm the life force hidden in old works of stone.

De generatione humanum: Deucalion and Pyrrha (ca. 1636)

The latent force of earth mixed with liquid and heat is the subject of Rubens’s late oil sketch Deucalion and Pyrrha (ca. 1636; fig. 3a). Created, like the oil sketch for The Discovery of Tyrian Purple, for the Torre de la Parada cycle, it depicts the regeneration of the human race following the cataclysmic flood unleashed by Zeus.94 Deucalion was the son of Prometheus, who survived the deluge together with his wife Pyrrha by floating in a chest built by his artisan father. However, the couple was elderly, diminishing the chances for humanity’s survival. As the rains fell, the oracle at Themis told Deucalion: “Cover your head and throw the bones of your mother behind your shoulder.” Deucalion correctly interpreted this to mean rocks—the “bones” of Gaia—which he and Pyrrha cast behind themselves and which spontaneously metamorphosed into human beings.95 Thus, although not presented in the form of a statue, Mother Earth is once more allegorized in stone, a material that precedes the creation of life. The scene was most likely paired in the Torre de la Parada with another myth of spontaneous generation, Cadmus Sowing the Dragon’s Teeth.96 According to Ovid, Cadmus killed the dragon that guarded the spring of Ares. Lacking an army, Cadmus planted the dragon’s teeth in the earth, and the teeth immediately sprouted into armed warriors who began battling one another.97

Both images correspond to a period fascination with rocks, stones, and mineral formations as sites where the opposition between matter and form breaks down, exposing the “metamorphic potential of matter” itself.98 Fossils and legendary images believed to have been produced naturally within stones represented the concept of nature as artist, a driving aesthetic principle of collectors’ cabinets.99 Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) claimed that the first sculptures originated from early humans discerning the lineaments of bodies in a tree stump, a clod of earth, or other conglomerations of raw matter.100 Elsewhere, Alberti stated that “nature herself delights in painting,” citing such pictorial stones as an example.101 A related notion was that painters could take inspiration from the forms they perceived in clouds, stains, or other organic masses, or could even incorporate material accidents into their works by, for instance, throwing a sponge at the canvas.102 Rubens’s awareness of the art-theoretical topos of the “image made by chance” is shown by his late oil sketch Neptune Calming the Tempest (1635), which depicts the fugitive north wind, Boreas, as a cloud-figure (fig. 16).103 Created just one year later, the Deucalion and Pyrrha sketch seemingly takes such notions to the extreme by depicting a myth in which fragmented nature actually generates living bodies. There is a capriciousness to the act of throwing the rocks that, like the image of the Medusa’s spilling blood, situates creation within nature’s material flux. Here, however, humans are shown facilitating the creative process; Mother Nature, apparently, needs collaborators.

Deucalion and Pyrrha conduct their work in the muddy foreground before a temple. In the background we glimpse a sea, perhaps the flood receding. Above the uneven, wet-looking ground is a sky tinged with yellow, blue, and pink, the colorful brushwork punctuated by two tiny birds in flight. Deucalion hurls two rocks behind him while Pyrrha throws one rock and bends down to pick up another. Their hunched poses and long, bent arms convey a sense of syncopated, wheel-like motion. On the right stand their first creations, a naked couple who resemble Rubens’s earlier depictions of Adam and Eve.104 In contrast to the pugnacious warriors sowed by Cadmus, these figures turn to each other and embrace, as if about to begin procreating instantly.105 Other figures emerge from the ground: a male nude who looks up at the flying rocks as if awaiting his own mate, and two additional half-baked creations struggling out of the muck (fig. 17).

Origins and Prototypes

Illustrated Ovids from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, from which Rubens frequently drew pictorial inspiration, had depicted Deucalion and Pyrrha’s progeny as a group of infants or children crawling around the ground (fig. 18).106 Rubens’s decision to show these creations instead as adults, differentiated according to various states of finish rather than age, emphasizes the speed and spontaneity of this primordial anthropogenesis. It also more clearly distinguishes this “spontaneous” generation from the history of procreation that follows. Rubens’s reinterpretation of the scene also invites the viewer to compare the different types of human bodies the image shows. Muscular and gigantic, Deucalion and Pyrrha seem to belong to a different age of the earth than their soft, lissome progeny. This epochal juncture, the transition between two ages in the history of humans, may have implied a stylistic or art-historical break as well. Deucalion and Pyrrha are reminiscent of the sculptural, monumental figures of Michelangelo (1475–1564).107 Their robes, in particular, recall those of Michelangelo’s prophets and sibyls in the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. In contrast, the fleshy, pinkish nudes that sprout from the earth are distinctly Titianesque. This is not surprising, since Rubens’s conception of Adam and Eve was filtered through Titian (1490–1576), whose painting The Fall of Man he had copied in Madrid.108 The reference would have been recognizable to the work’s intended Spanish audience.

For Rubens and his viewers, the bald, naked humans still half-embedded in the earth may have evoked additional prototypes. They are reminiscent of late sixteenth-century sources that characterize the Indigenous inhabitants of the Americas as lacking form, spirit, and humanity until receiving it from their colonizers.109 In addition to the engravings of Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), which frequently emphasize the amorphous quality of the “new world” and its inhabitants,110 there are clear similarities between the anthropogenetic imagery of Rubens’s Deucalion and Pyrrha and the allegory of America from the print series titled Nova Reperta (New Inventions and Discoveries), executed after Jan van der Straet (1523–1605) and published in the 1590s by Philip Galle (1537–1612).111 In this print (fig. 19), the continent is allegorized as an Indigenous woman eagerly rising from her hammock as she is “awakened” by Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512). The image’s caption reads, “Amerigo rediscovers America; he called her but once and thenceforth, she was always awake.”112 In the rocky background, a fictionalized Indigenous group is shown practicing cannibalism. Huddled close to the earth, these earthly, inchoate bodies appear to be called to life, in the foreground, by the allegorical figure of America that rises through Amerigo’s Pygmalionesque act.

José de Acosta’s Natural and Moral History of the Indies (1590), a text Rubens owned and had used three years earlier as a source for the Pompa introitus Ferdinandi (a triumphal procession designed by Rubens and held in Antwerp in 1634),113 specifically mentions “Deucalion’s flood” in a chapter on “what the Indians tell about their origins”:

Some experts say that in those countries are many notable signs of some great flood, and I am of their opinion that these marks and signs of a deluge was not that of Noah, but some other particular flood such as that of which Plato speaks, or Deucalion’s flood, of which the poets sing.114

De Acosta’s text then maps these ancient floods onto an origin myth of the post-diluvial regeneration of the Incas out of Late Titicaca by the god Viracocha.115 The subjects of Rubens’s image—humanity and its natural history—were categories that were being intensively questioned and revised in early seventeenth-century Europe in response to such sources.116 Given that Rubens’s sketch was probably a preparatory model for a larger canvas sent to Madrid, an uncomfortable aspect of the work is therefore the rhetorical contrast or even racial hierarchy implied in its presentation of a blond, Titianesque Adam and Eve as the apotheosis of humanity.117

Technologies of Earth

Like the baby snakes emerging from the Medusa’s blood, the bodies that rise from the earth in Deucalion and Pyrrha are monsters—not in the sense of being chimeras, but in the sense of being incomplete creatures caught between matter and form. Hairless, faceless, and without apparent gender, they are indicated with a few smears of blue-gray, yellow, and brown over the ochre ground. One lies prone with one elbow bent, apparently trying to rise out of the muck. Triangular shadows appear in the crevices where this body separates from the ground, echoing the modeling of the rock that Pyrrha holds up against the sky. That rock’s three visible facets, in three shades of gray, suggest—like the drops of the gorgon’s blood—a kind of kernel or code for all three-dimensional bodies (fig. 20). Despite the association that Rubens’s early biographers made between his art and colore (coloring), as opposed to disegno (design), Deucalion and Pyrrha reveals an equal fascination with the potency of light and dark and how the “seeds” of images are contained in the rudiments of volumetric form.118

Rubens’s sketch also relates the collaboration between painting and Gaia to the fluctuating and mixed materiality of paint. Indeed, its earliest viewers would have included other artists as well as learned connoisseurs, for whom painting’s techniques were increasingly of interest. Depicting nature as a technological realm, the image emphasizes the deep knowledge of materials and their transformation that was attributed to artisans in early seventeenth-century Antwerp and that was understood as a form of knowledge about nature.119

The lush brushwork and unblended, vibrating colors of Deucalion and Pyrrha communicate a material world in flux. Such painterliness is typical of Rubens’s late oil sketches, in which the poetics of spontaneity—the spontaneous generation of images—derive from rapid execution and what David Freedberg has described as an astonishing “fluency,” a near elision of thought and action.120 The fluency of Rubens’s late oil sketches is also a material-technical quality aided by the use of an actual fluid: turpentine. Particularly from about 1615, Rubens’s paintings show evidence of a substantial use of oil of turpentine, a solvent made from distilled pine resin.121 The significance of this liquid to Rubens’s technique is documented in a note in the “Mayerne manuscript.” This compilation of more than three hundred handwritten notes and recipes on artisanal technologies was assembled and transcribed between about 1620 and 1646 by Théodore Turquet de Mayerne, a Geneva-born physician whom Rubens knew.122 Held today in the British Library, the manuscript includes a technical note whose source it identifies as “M. Rubens”:

To make your colours spread easily, & by consequence to mix well, & even don’t die [ne meurant pas] . . . when painting, dip your brush lightly from time to time into the white oil of Turpentine from Venice extracted au bain M.[arie] then with the said brush mix your colours on the palette.123

Rubens thus appears to have practiced and advised distilling turpentine in a bain-marie, a heating vessel also used in alchemy (fig. 21). Dipping the brush in this warm liquid, the note suggests, allows the painter to control the viscosity of his colors and to preserve their liveliness.124 While the phrase ne meurant pas might be understood in a more practical sense as “not discolor,” the evocative reference to the possibility of colors dying also conceives of paint as an organic substance open to life-giving manipulations.

Scholars have noted how Rubens’s richly varied paint surfaces invoke the human body’s layers, an analogy also found in his theoretical writings.125 While Rubens’s impasto brushwork conveys the fleshiness and materiality of color, this is typically combined with translucent areas where paint is applied in thin layers or glazes, communicating the diaphanousness of human skin. Such thinly painted areas often reveal glimpses of the preparatory layer known in Italian as the imprimatura and in Dutch the doodverf (dead coloring).126 This layer, applied rapidly and with a coarse brush, is often incorporated by Rubens as a kind of special effect, imparting a dynamic atmosphere to his landscapes and the illusion of living, breathing flesh to his bodies. In Deucalion and Pyrrha, the doodverf supplies a visible basis for the fictive ground that is also Mother Earth herself, imbricating the technologies of nature and painting. Deucalion and Pyrrha’s first creations display this dual parentage—particularly the Ovidian “Eve,” who incorporates the earthy ground coloring in her torso and her hair.127 That such preparatory layers heavily feature earth pigments such as chalk and ochre would have given the analogy between color and Gaia’s bodily matter real material weight.

In the preface to his Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari (1511–1567) explicitly linked the Biblical creation of mankind to the earthly origins of pigments:

Now, the first model [modello] from which the first image of a man emerged was a lump of clay [terra]. And not without reason: because the divine architect of time and nature wanted to show perfectly in the imperfection of the material how to remove and to add, in the same way that sculptors do. . . . He gave [his model] vivid flesh coloring; and later on the same colors, derived from quarries [miniere]in the earth, were to be used to fashion [contraffare] all the things that occur in paintings.128

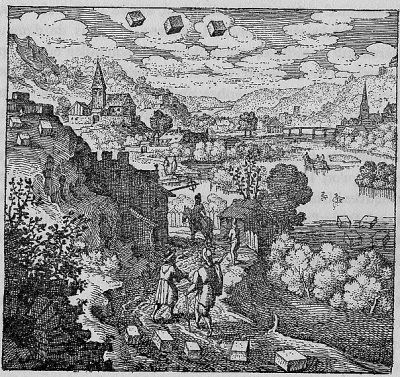

Deucalion and Pyrrha follows the progression in Vasari’s text from sculpture to painting. It emulates sculptural techniques—modeling, chiseling—in order to transcend them through color. This is especially apparent in the sky, the metamorphic space through which Gaia’s “bones” first pass on their way to becoming living bodies (fig. 22). Bridging the two sides of the composition, the sky’s brushwork displays an optical mixture of red, blue, and yellow mixed with white. The sky is reminiscent of discussions in the optical treatise by François d’Aguilon, which Rubens had illustrated and which was one of the earliest works to formulate the theory of red, blue, and yellow as the “primary colors.”129 Rubens’s sketch implies that these exemplary colors are necessary ingredients in the creation of truly living bodies, as is a quasi-alchemical mixture of the elements.130 The landscape’s Paracelsan overtones are further revealed through a comparison with an etched illustration in Atalanta fugiens (1618), an alchemical emblem book by the German physician and alchemist Michael Maier. The caption for a landscape etching created by the Swiss-German printmaker Matthäus Merian (1593–1650) and labeled as Emblem 36 (fig. 23) describes the philosopher’s stone being “cast upon the earth” (lapis projectus est in terras).131 In fact, Merian depicts the philosopher’s stone as three stones in flight, just as we see in Rubens’s sketch. As Michael Gaudio notes in a recent article on the Atalanta fugiens illustrations, “Merian represents the stones as cubes, and to accommodate their elemental course through earth, air, and water, he sets them within a flourishing river valley.”132

In Rubens’s sketch, the “dead coloring” comes to life in the postdiluvial landscape through the mixing of earth, water, air, and the fiery warmth in the sky, which crests in the pink and yellow streaks of impasto that run just under Pyrrha’s rock. Comparing elemental mixing to the mingling of the primary colors, the image elides the materials and technologies of nature and painting. Such details suggest Deucalion and Pyrrha as a case study for how a late Rubens oil sketch such as this could have functioned not just as a model for a finished, exported canvas painting but also as an art-theoretical and discursive object in its own right within the workshop.133 Associated with sculptural creation, its industrious, perpetually laboring Titans appear blind to the ultimate creative act, which takes place both within the mythological scene of spontaneous generation and at the level of its making.

Conclusion: Mythologizing Matter

Rubens’s images of spontaneous generation dramatize moments when a mythological substance—color, identified with nature’s bodily matter—becomes a medium of creation. The blood that oozes from the gorgon’s neck in Head of Medusa, the water that exits the Ephesian fountain in The Discovery of Erichthonius, and the rocks that hover over the “common ground” between Gaia and painting in Deucalion and Pyrrha: all of these articulate the materials of nature and painting seeping into each other. In two of these works, Head of Medusa and Deucalion and Pyrrha, nature actually becomes an artist, her creativity unfolding in narrative time. Intriguingly, in both, nature’s generative acts are performed by substances etymologically linked to Rubens’s name: the blood in Head of Medusa relates to Rubens (“reddening”), and the rocks in Deucalion and Pyrrha to Petrus, or Peter.134 Such references, if Rubens did intend them to be recognized by viewers, would merely have amplified what the images already emphasize: the inextricability of matter and making. Analogizing painting (if not the painter himself) with nature’s oscillations between matter and form, softness and hardness, wetness and dryness, stillness and motion, these works imply artistic agency as both external to and present within painting’s materials.

To conclude, let us briefly return to The Discovery of Tyrian Purple and its possible allusion to Cornelis Drebbel’s discovery of how to chemically manipulate cochineal red dyes. In a letter of 1629 to the French antiquarian Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, Rubens poked fun at Drebbel, whose work and physical appearance, he slyly noted, both fell apart under close inspection and were thus best viewed from afar—an insulting dig at Drebbel’s widely known experiments with microscopic lenses.135 In The Art of Describing (1983), Svetlana Alpers cites this letter as evidence for a broad distinction between Drebbel’s “technical and manipulative view of the world” and Rubens’s more “textual and historical concerns.”136 However, the works examined in this essay have shown that Rubens’s “technical and manipulative” understanding of his craft, informed by ideas about nature’s creativity and about matter itself, could structure his interpretation of ancient myths as much as his antiquarian erudition. Weaving together various originary realms—nature, antiquity, and the global geography through which Rubens’s materials and subject matter were constituted—these scenes of spontaneous generation situate painting at the crossroads.