This article assembles the evidence for the lifetime reputation of the Antwerp painter Jan de Beer (ca. 1475–1527/28), rediscovered by Georges Hulin de Loo and Max J. Friedländer in the early twentieth century. At the time of their publications little was known about the artist’s life, but the evidence now available concerning his important reputation includes archival sources published since Friedländer’s day, an unpublished contract, early literary sources, and reevaluations of the artist’s work for the guild and church. The factors involved in his late sixteenth-century disappearance from the historical record are also analyzed.

In 1902, while examining early Netherlandish drawings in the British Museum, the Ghent scholar Georges Hulin de Loo recognized the inscription in the upper left corner of a sheet of head studies catalogued by the museum as a work of Joachim Patinir (fig. 1).1 He identified the inscribed name–“Jan de beer” (fig. 2)–as the signature of an Antwerp painter known from the membership ledgers of the city’s St. Luke’s guild, the Liggeren.2 Hulin’s discovery, not published until 1913, represents the first time that a work of art had been linked to Jan de Beer since the artist’s death in 1527 or 1528.3

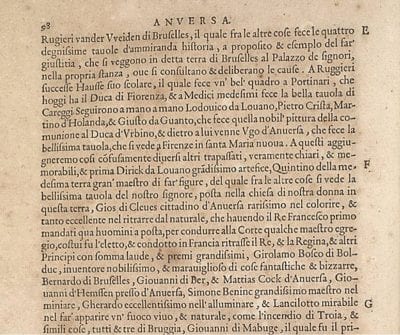

Building on Hulin’s discovery, Max J. Friedländer, in publications on Antwerp Mannerism in 1915 and 1933, reconstructed Jan de Beer’s oeuvre and reintroduced the artist to the history of early Netherlandish painting.4 When Friedländer undertook this difficult task, the only biographical information available about the artist was the five references in the Liggeren plus a nineteenth-century annotation added by the editors.5 Additionally, Friedländer drew attention to the fact that Lodovico Guicciardini had listed “Giovanni di Ber” in his compilation of famous Netherlandish artists, as part of his 1567 Descrittione . . . di tutti i Paesi Bassi.6 Guicciardini’s Descrittione included the first systematic, published canon of Netherlandish artists, almost certainly assembled in response to Vasari’s Vite of 1550.7

Thanks to a body of De Beer and De Beer-related documents discovered since Friedländer’s day, including a teaching contract being published here for the first time (see Appendix), and a reevaluation of an early literary source as well as selected works from the artist’s oeuvre, it is now possible to define the important reputation the artist enjoyed during his lifetime.8 Additionally, light can be shed upon the circumstances that led to the erasure of his memory immediately after the appearance of Guicciardini’s book.

Guild Activities

Among the multiple indications from Jan de Beer’s career that evoke his lifetime prominence are his service and work for the Antwerp painters’ guild. In 1509, a short five years after joining the St. Luke’s guild as a free master, De Beer was elected to the important guild office of elder (ouder or ouderman). This was unusually quick for such a high honor, and it positioned him in the midst of venerable company.

The relevant information comes from a 1509 municipal document concerning the appraisal of a large sculpted altarpiece by the Antwerp carver Peter Pauw, commissioned by the city of Dunkerque. The appraisal was carried out by the guild’s two deans, two sworn members, and three elders.9 Information exists for only five of these Antwerp guild officials, but relative to the other four, De Beer was conspicuously young. Quentin Metsys, one of the elders, had joined the guild eighteen years earlier; Cornelis de Geet, another elder, thirty-two years earlier. The dean, Gielis Wrage, had joined nineteen years previously; while Hendrik van Wueluwe, probably the artist known as the Master of Frankfurt and a sworn member, had joined twenty-six years earlier.10 The average length of guild membership of these four officers was twenty-four years, in contrast to De Beer’s brief five years. This is strong evidence of the artist’s rapid rise to preeminence soon after joining the guild, particularly when one considers that he would have been chosen from a guild membership that numbered an estimated one hundred master painters in 1508.11

Even before his 1509 election to the office of elder, De Beer had likely already come to the attention of the guild leadership. The first of three extant commissions that he undertook for the Antwerp guild appears to have originated early in his career, around 1504–9, based on stylistic indicators. At 84 x 144 cm, the canvas painting in Milan of Saint Luke Painting the Virgin and Child is one of the larger works in the artist’s oeuvre (fig. 3).12 It is a Tüchlein, his only surviving painting on linen, but its condition is poor. It was undoubtedly made for the guild’s chapel or the guildhall, or for use in a ceremony, since the guild’s emblem of three small shields upon a large shield is inscribed on the boss at the end of the towel rod.13

This painting is notable for its unusual iconography of an angel assistant grinding pigments in Saint Luke’s studio, shown at the rear, far right.14 The presence and activity of this angel has the effect of conferring divine sanction upon Luke’s art. Luke’s act of painting is represented as being the result of a heavenly collaboration between himself and one of God’s celestial helpers, presumably dispatched specifically to assist him in the creation of his sacred image of God’s son and his holy mother. This novel conception of Luke had the powerful effect of augmenting the saint’s status and the profession and practice of painting, plus enhancing the guild of which he is patron. The result was a new and flattering interpretation of Saint Luke as an artist. It seems reasonable to assume that this iconography would have been well received by the guild leadership.

Perhaps, in fact, it was the success of the Saint Luke canvas that prompted the guild to turn again so quickly to De Beer to design a glass roundel window.15 In his drawing of Saint Luke Painting the Virgin and Child (fig. 4), probably dating around 1509–10 and now in London, the sheet is pricked for transfer to the glass design.16 De Beer again represented Luke’s assistant as an angel. However, in contrast to its position in the Milan painting, the guild’s emblem is displayed front and center, hanging from the neck of Luke’s ox. This lost window was almost certainly made for either the guild’s chapel or its meeting hall. That it was held in considerable esteem is suggested by the probability that key features of its design were later adapted, in reverse, by Maarten de Vos in his 1602 altarpiece for the St. Luke’s chapel in Antwerp Cathedral.17

A second De Beer roundel for the guild was executed a few years later, probably around 1515, based on the model drawing of Saint Luke Recording the Annunciation to Zacharias, today in Lille (fig. 5).18 The guild’s insignia is again suspended from the ox’s neck. The larger size and stylistically later date of the Lille drawing indicate that it was not a companion to the London drawing, although it too is pricked for transfer. In the Lille sheet, Saint Luke’s book is open and his pen is at the ready. He is an eyewitness to the events described in the opening passage of his gospel (Luke 1:15–25), in which, as Zacharias performs a censing ceremony at the temple, the angel Gabriel appears and announces that Zacharias and his barren wife Elizabeth will miraculously bear a son, John the Baptist. Here, Luke is celebrated as an author (note the second book at his left knee). He is represented doubly, as an eyewitness to the event and as its historian, recording what he is privileged to see. Like De Beer’s representation of the saint’s angelic studio assistant, this interpretation of Luke is rare.

It may be that the Lille drawing was the first in a series of window designs depicting Luke as both witness and gospel author. At the very least, since Luke is represented as a witness to the Annunciation to Zacharias, which he alone recorded in his gospel, one would expect a companion roundel showing Luke as witness to and author of the Annunciation to Mary, which he also exclusively recorded.

De Beer, thus, probably created at least four works for the Antwerp St. Luke’s guild, and perhaps others yet. The basis, however, for identifying the three extant Luke pictures as guild work rests upon more than simply their inclusion of the guild’s coat-of-arms, though that is primary. It is also predicated upon the close administrative relationship De Beer had established with the guild (documented between 1509 and 1515), and the new and flattering interpretations with which he endowed the depiction of Saint Luke in these works. In the London roundel, it additionally connects to the circumstantial evidence that esteem for his window may have led De Vos, ninety years later, to create a new guild altarpiece embedded with a reminder of the guild’s earlier Golden Age.19

The guild work carried out by Jan de Beer positions him squarely within the company of other prominent sixteenth-century Antwerp artists, such as Quentin Metsys, Dirk Vellert, Frans Floris, and Maarten de Vos.20 However, the frequency of his work for the guild has no equal among the guild outputs of his celebrated peers.

Civic Activity

De Beer was also chosen to design a window for what was then the parish Church of Our Lady, today Antwerp Cathedral, the largest Gothic church in the Netherlands. Only the window’s two central panes, portraying the monumental figures of Saints John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, reflect the artist’s original design (fig. 6).21 This window was a particularly prestigious commission, situating the artist, again, in the company of other luminaries, in this case Dirk Vellert, Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Aert Ortkens van Nijmegen, Jan Hack of Brussels, and Nicolaas Rombouts of Leuven, each of whom had designed a window or windows for the church between 1500 and 1540.22 Within this group, only De Beer and Coecke were primarily panel painters rather than specialists in glass windows.

Although the heavily restored window exists today only as a fragment of the original, nevertheless it carries enormous historical significance.23 The Two Saints John window is one of only three early, Antwerp Cathedral windows to have survived the great fire of 1533, which badly damaged the massive church that had only just been completed in 1521.24

A Pupil from Ghent: Lieven van Male

The spread of Jan de Beer’s reputation outside Antwerp is vividly demonstrated by the recently rediscovered existence of a pupil from Ghent, who sought him out for advanced artistic training. The account of this new chapter in the artist’s career comes from a 1516 Ghent contract, reference to which, in Frans de Potter’s nineteenth-century history of Ghent, was discovered by Lorne Campbell, who graciously shared it with the author.25 The document (fig. 7a, fig. 7b, and Appendix) concerns twenty-six-year-old Lieven van Male of Ghent, who on July 1, 1516, entered into a contract with Jan de Beer for two years of instruction “to learn the art of painting” (te leerne de conste van scilderien, fig. 7b). This contract is the legal account ratified and recorded by the Ghent aldermen, based upon an earlier (oral?) agreement of June 21 between the two parties, at which time Lieven made a deposit of earnest money. The written document is one of the more remarkable artistic sources for the period, one of only two known early Netherlandish contracts to specify the cost of artistic training for a defined period of time.26 Given its significance, it is worth translating in full:

Lieven van Male, son of Jan, apothecary, is 26 years old and himself a legal adult, [and together with] Lysbette vanden Beerghe, his mother and widow of the same deceased Jan, acknowledge that, with Martin and Michiele Bennins, brothers and the sons of Martin, both merchants, [they] have answered and pledged a guarantee before Lieven, each for the other and one for all, to Janne den Beer, painter of Antwerp, [for the] payment of the sum of 9 pounds groats of Flemish money, for which Lieven himself has drawn up the contract with Janne, made and done for Janne to teach him the art of painting for the time and term of two years’ duration. [This agreement] was entered into the 21st day of June last, at which date he [Lieven] paid the ready money of 2 pounds 5 shillings. [The remaining amount is due as follows:] 2 pounds 5 shillings at the following Christmas Eve, 1516; 2 pounds 5 shillings at St. John’s Mass [June 24]; and 2 pounds 5 shillings at Christmas Eve, both in 1517. In the second place, [should] Lieven require an exemption and exception, [then] Lieven and the aforesaid Lysbetten, his mother, [and] the aforesaid brothers Martin and Michiele, [in] debt for the outstanding and overdue sum of 9 pounds groats of Flemish money, promise to pay and hand over the entire [amount] within three years of the initial [contract] date; or to pay and hand over the shortfall [from] the sum of 9 pounds groats of the aforesaid [debt] to pay the value of 10 shillings as an annual, hereditary annuity, [the interest on which is] 18 pennies [= 15 percent], due the first day of each hay month [July] in each year after the first payment, which falls on the first day of hay month in 1520, and commencing from then forth, year to year, on each consecutive day of hay month, 10 shillings in perpetuity and hereditary [payment] or until its discharge, from paying the aforesaid sum of 9 pounds groats [by] making up the shortfall through paying the annual rent. In addition, the [Bennins] brothers acknowledge and safeguard the 3 pounds 5 shillings groats that will be given up and paid if Lieven leaves his master during the two years of his instruction. The same Lieven and his mother and the brothers acknowledge and guarantee, on behalf of the contracting party [Lieven], and on behalf of the pledges, this surety for one and the other, above all. To insure [their] pledge, the aforenamed Lysbette, Lieven’s mother, puts [up] her house and property, including the garden and rear house, plus all her belongings, from front to back, [located] near the house of Saint George at the Waal Bridge [Waelbrugghe: in Ghent], [between the house of] Jacop Vriendt, her nephew, on the [one] side, and Lieven Lievensz, baker, on the other. The tenant’s rent, in service as rent,[is] worth [the value] or payment of the aforesaid 9 pounds groats. [This constitutes] a new assurance and counterpledge for the sum, [in which] the brothers [have] 10 days to pay the aforesaid sum or rent, which must be charged to them if they fail in payment. [This is based on the value of] her goods and the forenamed house and property which comprise the place. [Therefore,] in [this] other way, to be maintained according to the law of this city, from the same rent the payment of the aforesaid 9 pounds groats of principal can be discharged. [It will] cease [being paid as] rent on the day of discharging such money. [This contract is a legal] act [ratified on the] 1st [of] July 1516.27

What makes this document so extraordinary is that two years earlier, on March 20, 1514, Lieven had already enrolled in the Ghent painters’ guild as a free master.28 In 1516, therefore, he was contracting with De Beer for two years of advanced training after having been previously established as a guild master. In effect, he was arranging for a “post-doc” in Antwerp.

The contract stipulates that De Beer was to teach Lieven for two years for a fee of 9 pounds groats Flemish, which is the equivalent of 13.5 Brabant pounds. This is a very expensive sum. It is greater, for example, than the price of Patinir’s Korte Gasthuisstraat house in Antwerp, purchased in 1520 for 10.9 Brabant pounds; and it is the equivalent of two years’ salary for an Antwerp bricklayer of the time.29 More remarkable yet, De Beer’s fee is an astonishing six times the amount of the apprenticeship fee—2.25 Brabant pounds—paid in 1502 by Henric Henriczoon to the celebrated Ghent miniaturist Gerard Horenbout for two years’ instruction.30 Though De Beer was providing advanced training, the fact that he could charge six times the amount that a beginner would pay for illumination instruction from a prominent contemporary is clear evidence of Jan de Beer’s elevated reputation.

As insurance for the payment, three guarantors stood warranty: Lieven’s widowed mother, Lysbette vanden Beerghe, and two Ghent merchants, the brothers Michiel and Martin Bennins. The Benninses agreed to guarantee the 4.9 Brabant pound penalty that would apply if Lieven left De Beer’s training before the two years of instruction were up. For her part, Lysbette put up her house by the Waal Bridge in Ghent, along with all her belongings, property, and the rear house as collateral for the cost of her son’s training in the leading art center of Antwerp. The contract also outlines several alternative payment plans in case of default or difficulty in meeting the original payment arrangements.

In seventeenth-century Holland, for which much more documentation exists, John Michael Montias found abundant evidence of a correlation between the cost of artistic instruction and the teacher’s reputation.31 In this regard, the young Rembrandt can be taken as an example. In accepting the second pupil of his career, the orphaned Isaac Jouderville, in 1629, Rembrandt, living in Leiden, was paid 100 guilders for two years’ instruction. This was double the 50 guilders fee which at the time, in nearby Delft, represented an unusually large payment. Scholars have taken this large fee as proof of Rembrandt’s high reputation at a young age.32

Lieven van Male might have become aware of De Beer’s reputation through Michiel Bennins, the Ghent family friend who served as one of the 1516 guarantors. The previous year in 1515–when De Beer was guild dean and his civic profile was at its highest–Bennins had joined the prestigious Antwerp confraternity of Our Lady’s Praise (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-Lof), the largest fraternal guild associated with the Church of Our Lady. The guild’s accounts record Bennins’s payment of his membership fee that year: “Received from Michiel Bennins, merchant of Ghent, 1 pound 10 shillings.”33

Why did Lieven undertake post-mastership training when it was so expensive that it required three guarantors plus the collateral of a house, its goods, property, and rear house? Two hypotheses come to mind, each of them probably operative. On the one hand, if market and social forces in the Netherlands were comparable to those in contemporary Italy, which seems likely, then Lieven may have instinctively understood that advanced training in the art capital of the north, with a prominent artist like De Beer, would significantly increase both his status and income prospects when he returned to Ghent to establish his independent practice. This correlates to patterns discovered by Michelle O’Malley in her study of artists’ commission-documents in Renaissance Italy. She demonstrated that Italian patrons placed an especially high value upon work by artists who had trained in a major art center, such as Florence, Siena, Milan, or Venice. This preference, together with apprenticing with a master of elevated status, translated into higher prices paid for these artists’ work, relative to the prices paid to artists without such elite training.34

Another explanation could be that Van Male wanted to learn to paint in the fashionable Antwerp Mannerist mode of the day, exemplified by De Beer’s art, in order to take that knowledge and skill with him back to Ghent. This assumes that the Mannerist mode was in demand in Ghent, and that local painters and dealers were unable to satisfy this demand. Certainly it is clear that the Antwerp manner was popular in other Flemish cities as well as abroad. This is seen, for example, in Bruges in the shop of Adriaen Isenbrandt; and in France, where Antwerp Mannerist imagery was widespread during the early sixteenth century.35

A Pupil from Liège?: The Lambert Lombard Puzzle

It is virtually certain that De Beer was also engaged for art instruction by a second pupil from outside Antwerp, the young Lambert Lombard of Liège. However, the particulars claimed by the principal source in this case and those inferred from other contemporary sources are in conflict.

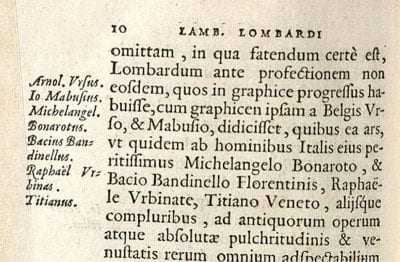

For centuries it has been traditional to regard Lombard’s first teacher as Jan’s son, the painter Aert de Beer (ca. 1508–1538/40). The basis for this belief is Domenicus Lampsonius’s biography of Lombard, published in 1565: Lamberti Lombardi apud Eburones pictoris celeberrimi vita. Lampsonius’s account states that Lombard learned drawing from the artists Ursus and Mabuse (fig. 8). The relevant text reads: “It certainly must be said that Lombard, before his departure [to Italy], did not advance as much in it [architecture] as he did in the art of drawing. The reason was that he had learned drawing from the Belgians Ursus and Mabuse.”36 Since Ursus means bear, which in Dutch is de beer, the reference clearly meant the Antwerp painter De Beer. But was it Jan the father or Aert the son? The annotation in the margin of Lampsonius’s text specifies “Arnol. Vrsus,” that is, Arnold the Bear or Aert de Beer.

In her 1990 monograph on Lambert Lombard, however, Godelieve Denhaene argued that the start of Lombard’s training more likely occurred at the hands of Jan de Beer rather than Aert.37 She pointed out that Lombard was born in Liège in 1505 or 1506, and that Jan was a master in 1504 but that his son, Aert, did not become a free master until 1528 [actually 1529].38 This makes it inherently unlikely that the latter would have been Lombard’s teacher, notwithstanding Lampsonius’s annotation.

The salient points of Lombard’s early life can be summarized as follows. Lampsonius claims that Lombard had an early love of painting, that he knew when he was young that he wanted it as his profession, and that he did not delay in starting to make progress toward it.39 It is known that he traveled to Middelburg in the mid-1520s to meet Jan Gossart.40 Maryan Ainsworth dates this event around 1525.41 Lombard married in 1527 and remained in Middelburg, where he briefly established his own studio.42 By around 1528 he was back in Liège; and again in 1532 he is documented in Liège.43

If Lampsonius’s text is taken literally, namely, that Lombard first studied with De Beer and secondly with Gossart, and that his training concerned instruction in drawing (traditionally the beginning phase of painting instruction), then Jan de Beer, not Aert, must have been Lombard’s first teacher. By the early 1520s, when Lombard would have been around fifteen years old, the traditional age for starting an apprenticeship, Jan de Beer was a mature, esteemed artist, with an established reputation. The following sequence conforms to the normal patterns of the time: Lombard, drawn to a painting career at a young age, likely started training with Jan in Antwerp around the usual age of fifteen or so, sometime in the vicinity of 1520–24.44 He next moved to Middelburg around 1525 to continue his studies with Gossart. There, he opened a studio and married in 1527. Soon after marrying, around 1528, he returned to Liège. In the alternative scenario, with Aert de Beer as his teacher, Lombard would have first trained with Gossart in Middelburg (ca. 1525), returned to Liège (1528), and then moved to Antwerp sometime between 1529 (when Aert became a master) and 1532 (when Lombard is documented as being back in Liège). Aert is unlikely to have established an important reputation that early in his career, and certainly his stature would not have been anything like Gossart’s at the peak of his career. Switching from a famous teacher to a much lesser one contravenes the typical patterns of the time, as does completing artistic training after marriage rather than before.45

A recent suggestion, seeking to reconcile Lampsonius’s text by supposing that Lombard was a journeyman rather than a pupil of Aert de Beer and Gossart, between 1529 (Aert’s mastership) and 1532 (Gossart’s death), is not plausible.46 At the end of the day, when all the above factors are taken into account, the marginal annotation of “Arnol. Vrsus” in Lampsonius’s Vita is more likely to be a puzzling error than a statement of fact.

Guicciardini’s Testimony

The most important proof of De Beer’s sixteenth-century reputation comes not from his lifetime but from forty years after his death, when Lodovico Guicciardini included Jan de Beer in his list of the fifty-one most important Netherlandish panel painters from Jan van Eyck to Hans Vredeman de Vries. Since De Beer is listed in Guicciardini’s canon as a name only, with no other particulars (fig. 9)–the same applies to Bernard van Orley, Herri met de Bles, and Marinus van Reymerswaele, for example—it is apparent that, by the 1550s or early 1560s, Guicciardini or his sources knew nothing of De Beer other than his name and reputation.47

Lodovico Guicciardini had relocated to Antwerp from his birthplace of Florence in 1542, just shy of his twenty-first birthday. He had gone there to help his brother run the family banking business, but when it went bankrupt in 1545 he ended up staying in Antwerp the rest of his life. In the city, he moved in the leading intellectual circles, made friends and contacts with highly placed humanists, merchants, and politicians, and followed the city’s flourishing artistic and rhetorician culture. It is known that he started research for his Descrittione in the 1550s and that he was a scrupulous investigator who sometimes paid for information, since his “main concern was the accuracy of his statements.”48 The high level of content accuracy in the Descrittione has been frequently noted in the literature.49 Given Guicciardini’s twenty-five years of Antwerp residency prior to its publication, his text can be taken as a reliable source for Antwerp artists.

In addition to testifying to the survival of De Beer’s reputation forty years after his death, Guicciardini’s account furnishes other critical information. Specifically, it reveals which Antwerp panel painters from the teens and 1520s were still regarded, in the 1550s and 1560s, as being the most important painters of their generation. Guicciardini singles out four Antwerp panel painters for immortality during these years. Using his order of listing, they are: Quentin Metsys, Joos van Cleve, Jan de Beer, and Joachim Patinir.

The stature of Metsys, Van Cleve, and Patinir has seldom been contested by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers or by modern historians, but the inclusion of De Beer within this elite group is unexpected. Given his late sixteenth-century oblivion, he has never enjoyed the approbation of the others, whose fame remained intact. This makes his original position within their select company especially significant. When the calculations of Maximiliaan Martens are factored in—namely, that the number of master painters working in Antwerp around 1520 was about 150—then De Beer’s presence in the inner circle of the four most eminent painters, from such an enormous field of potential candidates, takes on even greater significance.50

Oblivion

A year after Guicciardini had certified De Beer’s status, Vasari published the second, expanded edition of his Lives.51 In it he added a section devoted to “Various Flemish Artists,” prompted mainly by Guicciardini’s example, although probably also by correspondence with Domenicus Lampsonius, Lambert Lombard, and contact with several northern artists in Florence.52 Vasari, whose extensive dependence on Guicciardini has often been stressed, for the most part repeated Guicciardini’s list of Netherlandish painters.53 Unfortunately, however, there were significant omissions. Specifically, Vasari’s list of artists drops eight of the forty-four sixteenth-century painters cited by Guicciardini, the first of which is Jan de Beer. The other seven omissions are: Karel Foort, Adriaen Thomasz Key, Anthonis van den Wyngaerde, Gillis Coignet, Crispin van den Broeck, Hendrik van den Broeck, and Hans Vredeman de Vries.

In comparing Guicciardini’s and Vasari’s accounts, it has been observed that “of the two versions, the one by Guicciardini is . . . by far the more accurate.”54 Elsewhere in Vasari’s Vite, it is evident that he was not always well informed about art in the Netherlands. In his life of Michelangelo, for example, he erroneously describes the Bruges Madonna as a bronze relief tondo, even though Vasari was on close terms with Michelangelo and should have known better.55

It is not known why Vasari dropped these eight Netherlandish painters. One might speculate that he may not have had access to external sources that could verify the stature of these artists, in contrast to others in Guicciardini’s list for whom perhaps he had been able to secure confirmation. On the other hand, Vasari did have a copy of Lampsonius’s biography of Lombard, in which it was recorded that Lombard’s first teacher was the Belgian artist Ursus.56 Perhaps this reference was invalidated for Vasari by the information in Lampsonius’s biography claiming Aert de Beer as Lombard’s first teacher, whereas Guicciardini had named Jan as the famous De Beer artist. Yet there may have been a more essential reason at play. Vasari may not have had access to Guicciardini’s final, published account in time for his revised book. Because the timing of Guicciardini’s publication and Vasari’s is a mere year apart, Hessel Miedema has conjectured that Vasari may not have copied Guicciardini’s account but instead relied upon a second, now lost text for his information.57 If that was the case, there is no way of knowing if the lost source matched the final version published by Guicciardini. Moreover, Miedema finds evidence that Vasari “seems to take particularly scant interest in the facts he is relating” about northern artists, an indication that he was less than scrupulous in his approach to the Flemish material in his second edition.58Whatever the explanation, it is necessary to keep in mind that each of Vasari’s eight omissions concerns an Antwerp artist, with the exception of Karel Foort, who was from Ypres. This is significant since Guicciardini, an Antwerp resident for twenty-five years, was better positioned to be well-informed about Antwerp artists than Vasari was in distant Florence.

Vasari’s omission of De Beer from his 1568 canon dealt a fatal blow to the artist’s memory. From that point on, all published references to the artist disappear, save for later reprintings of the Descrittione. De Beer’s obliteration was quickly cemented by the publication of the Effigies in 1572, a joint work of Domenicus Lampsonius and Hieronymus Cock.59 Their Pictorum aliquot celebrium Germaniae inferioris effigies, in preparation by 1570 and perhaps as early as 1569, was a more substantial project than Guicciardini’s or Vasari’s.60 It was also more selective, reducing Vasari’s northern canon by almost half. Needless to say, Jan de Beer, like many other painters that had been listed by Guicciardini, was excluded from the Effigies, and from that point on the influence of Guicciardini’s account was decisively eclipsed. In 1604, Karel van Mander relied on Vasari and Lampsonius/Cock when he published the Schilder-Boeck; nor was Guicciardini’s list used by subsequent writers on Flemish art.61 Guicciardini’s Descrittione had addressed a broad overview of the entire Netherlands, of which his account of artists formed but a subsection, albeit a singularly important one. Both Vasari and Lampsonius/Cock, on the other hand, had created the earliest autonomous, dedicated accounts of Netherlandish artists, and as such their versions, not Guicciardini’s, became the building blocks for future canon formations.62

From 1568 to 1902, until Hulin de Loo recognized Jan de Beer’s signature on the London drawing, the artist was entirely forgotten. Ironically, it was his son, Aert de Beer—for whom no known work survives—whose memory endured over the centuries, owing to Lampsonius’s marginal reference to him and to his brief inclusion in van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck.63

Conclusion

It is clear from the foregoing that Jan de Beer had established an important reputation in the Antwerp painters’ guild, and in the city, during his career. He was repeatedly engaged by the guild for work, elected to high office early in his guild membership, and chosen for a prestigious window commission by the stewards of the Church of Our Lady. By mid-career his reputation extended beyond Antwerp to Ghent and probably also to Liège. Proof of his stature is furnished by the unusually large fee he commanded from Lieven van Male for advanced training. The survival of his fame was recorded by Guicciardini forty years after his death. Even without considering De Beer’s numerous artistic achievements, the biographical evidence assembled here validates Guicciardini’s claim. The Italian author’s positioning of Jan de Beer within the elite company of Metsys, Patinir, and Van Cleve, as one of the four most important Antwerp panel painters of the early sixteenth century, is congruent with his reputation in the historical and artistic record.