Two documents in the Amsterdam City Archives, recently made accessible through databases, augment our knowledge of Italian paintings in the Netherlands around 1635. The 1633 inventory of Samuel Godijn and the 1638 list of paintings owned by Lucas van Uffelen and Jacomo Noirot include works by Palma Giovane, Guido Reni, and Giuseppe Ribera. While these paintings have not yet been identified with extant works, their visual character may be suggested by analogy with other pieces.

Recent scholarship on Italian art in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century is lively indeed. Well known are the collections brought to Holland en bloc by Gerard Reynst (ca. 1630) and Aletheia Talbot, Lady Arundel (1646).1 The tax collector Nicolaes Sohier (1588–1642) assembled a choice group of twenty-four paintings, largely Venetian.2 Several merchants imported Italian art, including Hendrick (1584/89–1661) and Gerrit Uylenburgh (1626–1678), who conducted extensive business throughout Europe in antiquities and paintings.3 Elisabeth Coymans (1595–1653) and her five sons dealt in luxury goods from both the Caribbean and Europe; between 1649 and 1653 they shipped a quantity of Italian paintings and sculpture to Amsterdam.4 The general circumstance that many more Italian paintings were in circulation has long been suspected but hard to prove. Two documents, one involving a lesser-known collector and the other, a famous one, add to the mounting evidence that a variety of grand works by living Italian artists were in Amsterdam collections by about 1630.

The Godijn Collection

Samuel Godijn (1561–1633), a wealthy merchant and one of the early investors in the V.O.C. (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), had a substantial art collection. Its contents are known only through the inventory of his possessions in his house on the Keizersgracht, taken at his death.5 In 1613, he sold a number of moderately priced paintings and various other goods in the Orphans Chamber.6 This suggests that he was culling his possessions, perhaps in order to collect on a more refined level. The paintings listed in the 1633 inventory reflect a broad range of subjects and valuations.

Of the seventy lots of paintings and drawings, thirty-four are by named Dutch and Flemish artists, and thirty-six are anonymous, but presumably these are primarily Dutch and Flemish, since they are described as portraits, genre, and still-life subjects, types commonly found in Northern inventories. Nearly all of the named artists were active during Godijn’s lifetime in Antwerp, Utrecht, and Holland, including Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Gilles van Coninxloo (1544–1607), Cornelis van Haarlem (1562–1638). Frans Floris (ca. 1519–1570), Gillis Mostaert (ca. 1528/29–1598), Hendrick van Steenwijck (ca. 1550–1603), Roelant Savery (1576–1639), and Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638). Exceptionally, Godijn owned a portrait by Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441); this suggests that he was interested in the earliest of famous Northern painters, perhaps considering forming a survey of Northern painting.7 Most of the anonymous paintings were valued at less than 70f, but the attributed paintings were generally valued at around 100f. Among the highest valuations of the Northern paintings are the Mostaert (Masquerade Dance) at 300f; the Coninxloo (Landscape) at 240f; the Brueghel (Fish Market Scene), at 240f; the Floris (Banquet of the Gods) at 200f; and the Savery and Van Haarlem (Venus and Adonis) at 200f.8

Although Godijn’s collection was overwhelmingly composed of Northern art, it had notable Italian items. Six paintings are by named Italian artists:

Jacopo Bassano, Noah’s Ark

Jacopo Palma Giovane, Judgment of Midas and Flaying of Marsyas (pendants)

Jacopo Palma Giovane, Dance of Children

Guido Reni, Sophonisba and Masinissa and Sophonisba and Masinissa’s Servant (pendants)

These six works were among the most highly valued: each Reni at 400f, the Bassano at 300f, the Palma Giovane pendants at 150f each, and the Palma Dance of Children at 180f.9 None is identified today, but the Bassano and Palma paintings may approximate known works. Several versions of Noah’s Ark by Bassano (ca. 1510–1592) (fig. 1) are known; the one illustrated here is typical in its crowded foreground of animals and people, ark in the background, and general bustle of activity.10 The Dance of Children by Palma Giovane (ca. 1548–1628) may be akin, or even identical, to the painting now in the Six Collection in Amsterdam.11 The paired canvases by Palma Giovane may tentatively be identified as, or at least similar to, the large paintings in Braunschweig, Midas Judging the Contest between Apollo and Marsyas (fig. 2) and Apollo Flaying Marsyas (fig. 3).12 In both of these horizontal canvases, Apollo is at the center. The first highlights Apollo’s musical performance, as Midas and Marsyas sit and listen at either side. In the second, Apollo begins to skin Marsyas, whose goat legs are bound with rope and whose arms are tied to a tree, as Midas, wearing a crown and ass’s ears, watches from the side. The discarded pipes and violin in the foreground indicate the cause of such punishment.

Remarkably, Godijn owned two paintings by Guido Reni (1575–1642), whose works appear in very few Dutch collections at this time. One portrayed the forbidden love affair of the Carthaginian princess Sophonisba, enemy of the Romans, and Masinissa, ally of the Romans. The other depicted Sophonisba receiving from a servant the poison that would end her life; she chose suicide rather than become a prisoner of the Romans. The story of Sophonisba was a standard in history compendia and was often dramatized in Italian, English, French, and Dutch plays.13 No representations of these subjects are known by Reni, although many of his works involve similarly distressed women in difficult situations.14

The pendants by Palma Giovane and Reni would have been grand pieces by the foremost artists of their generations painted at the peak of their careers; possibly they were even commissions. One set is mythological, and the other historical. Both present a sequential narrative. They share the quality of physically devastating consequences brought about by willful challenges to authority. Marsyas has challenged Apollo and must pay the painful price of being skinned; Sophonisba has defied her identity as Carthaginian princess to have an affair with the Roman ally Masinissa. As unusual complements, they would reflect the moral and physical consequences of disobedience.

Thus, Godijn owned recent paintings by Italians and Northerners, as well as some notable examples of earlier artists, and his collection included a range of subjects, from mythology, history, and landscape to still life, portraiture, and genre. Adding to the deliberately constructed nature of the collection are the sculptures. Godijn owned 128 small alabaster pieces. About half of these were “keysers,” presumably a series of Roman emperors, their consorts, and other rulers. The rest were small figures, with no subjects given. These apparently were in two sizes, as they were valued at either 2f or 7f for each group of five or six statues. It is likely that these were copies of ancient and recent works, possibly including replicas of well-known pieces by Giambologna (1529–1608) and Michelangelo. As a large group of items, unified by material, they were likely commissioned by Godijn as a coherent group.15

According to the inventory, the artworks were mainly in five rooms, and the arrangement seems to have been planned for display. The voorhuys contained alabasters and a small plaster sculpture of a man. Small genre paintings were in the kitchen. The Italian paintings were featured in two rooms: the Palma pendants and Children Dancing were in the groote saal, the Reni pendants and the Bassano Noah’s Ark in the syde camer. Each of these rooms also contained around fifty of the alabasters and smaller paintings by Northern artists. The arrangement was calculated to impress the visitor.

The Lucas van Uffelen Collection in Amsterdam

Born in Amsterdam, Lucas van Uffelen (1580–1637) lived in Venice from 1615 until about 1632, when he returned to his hometown and settled at Keizersgracht 198, in the neighborhood where other eminent merchant-collectors, including Godijn, also lived.16 In Venice, Van Uffelen had prospered as a merchant banker and shipowner, and after the Venetian government claimed back taxes in 1630, he returned to Amsterdam. He collected art and patronized a number of artists while in Venice and apparently continued to collect after relocating to Amsterdam. Our knowledge of Van Uffelen’s collection is fragmentary. Van Uffelen’s holdings are known from a few extant paintings and inferred from various other sources. In addition to paintings and sculptures, Van Uffelen had a substantial collection of works on paper.17 Art collecting was in his family, as his father, Hans van Uffelen (1576–1613), who was a merchant in Italy and Spain, had a respectable collection of Northern paintings.18

It is well known that sales of Van Uffelen’s collection took place in 1637 and 1639 at the Orphans Chamber, but information about the contents and purchasers is scant. No trace exists of the 1637 sale, but the auction of April 9, 1639, attracted international attention. Unfortunately there is a break in the records of the chamber auctions during this period. A published sales catalogue was produced for the 1639 sale, but no copy survives. At the 1639 sale, two exceptional portraits were auctioned. Raphael’s Baldassare Castiglione (Musée du Louvre, Paris) was purchased by Alfonso Lopez and Andrea Odoni by Lorenzo Lotto (ca. 1480–1556) (National Gallery, London), by Gerard Reynst.19 Raphael’s Castiglione was the most expensive single item at 3,500f, as recorded by the underbidder, Joachim von Sandrart. The Van Uffelen sale prices were astoundingly high for an Orphans Chamber auction. The price of the Castiglione was nearly five times the value of the most expensive item sold during the previous forty-one years–an album of paper art by Lucas van Leyden (ca. 1494–1533).20 Rembrandt’s drawing of the Castiglione, made at the auction, noted its high price and the total of all pieces sold in the “cargaison,” which might indicate that a shipment of Van Uffelen’s collection had just arrived in Amsterdam.21

A clue as to the specific paintings owned by Van Uffelen is provided by a document of 1638 that lists twelve paintings then in his house.22 Jacomo Noirot (d. 1638), a business associate of Van Uffelen, was an owner or part-owner of this group, and his heirs wished to settle his debts. First noticed by J. M. Montias, this document suggests that Van Uffelen and Noirot were partners in art dealing. Four of these twelve works are by named Italian painters:

Bassano, De Vrede van Ytalien (The Peace of Italy)

Bassano, De vier heijligen van de Kerck (The Four Evangelists or Church Fathers)

Giovanni Contarini, Appoollo ende Diana (Apollo and Diana)

Guido Reni, Twee worstelende Cupidos (Two Wrestling Cupids)

The Bassano family and Giovanni Contarini (1549–1605) represent painting in Venice after the death of Titian, and Reni, current Bolognese art. Reni’s wrestling cupids are known in several versions with three pairs of cupids (fig. 4); Van Uffelen’s version apparently was a variant with one pair.23 Among the five anonymous paintings, at least two could be Italian:

Een Lieve Vrouwe (A Virgin Mary)

De Raet van Venetien (The Council of Venice)

Two other paintings are by Dutch artists who had lived in Venice: De negen musen (The Nine Muses) by Francesco (François) Badens (1571–1618) and Een Masquerade by Dirck de Vries (active 1590–92). Noirot’s paintings have a distinct Venetian emphasis. However, the valuation of these paintings is 15f or less for each. Perhaps they were small paintings; perhaps they were not necessarily an impressive or valuable group; or more probably, the paintings were valued according to Noirot’s investment in them.

Van Uffelen acquired art by artists whom he knew personally or who were recommended to him by his friends. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) painted two portraits of Van Uffelen (fig. 5), probably during the artist’s visit to Venice in 1622–23.24 Sandrart, who met the collector in Venice in 1628–29, advised him to acquire a life-size marble sculpture, Cupid Carving His Bow, by Jerome Duquesnoy (before 1570–1641). Displayed prominently in Van Uffelen’s Amsterdam house, Duquesnoy’s Cupid was acquired by the Amsterdam burgomasters after Van Uffelen’s death, for the extraordinary price of 6,000 guilders, as a gift for Amalia van Solms.25

Van Uffelen owned five paintings by Giuseppe Ribera (1591–1652), according to Sandrart. These were the four tortured giants Tityus, Tantalus, Sisyphus, and Ixion, and the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew. Van Uffelen’s giants have been identified as a series now in the Prado and are probably copies after lost originals.26 They constitute a series separate from another one, considered autograph.27 Ribera, born in Spain, was active in Rome and Naples and enjoyed Spanish and Italian patronage. Among the Northerners living in Italy who owned his paintings were the Flemish merchants Gaspar Roomer and Jan and Ferdinand Van den Eynden.28 The canvases in Van Uffelen’s possession typified Ribera’s dramatic chiaroscuro and graphic violence and complemented the Venetian emphasis of the collection.

Sandrart, clearly very familiar with Van Uffelen’s collection both in Venice and Amsterdam, described it as a “weitberühmten Kunstcabinet.” For its variety of subjects and the quality of its paintings, this collection would have been remarkable in Amsterdam. Its noteworthy impact in Amsterdam may be traced through several paintings by Rembrandt and his pupils. The Castiglione inspired Rembrandt and Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680) repeatedly in their self-portraits made around 1640.29 The Ribera paintings fit into a fashion for gruesomeness in Dutch painting. Perhaps they helped inspire Rembrandt in his 1636 Samson Blinded (Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt).

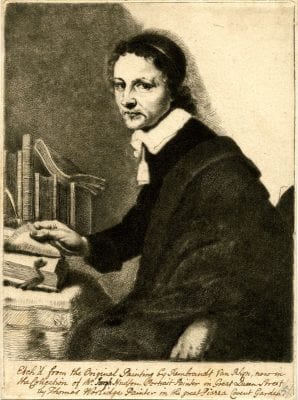

Van Dyck’s stunning portrait of Van Uffelen in his sumptuous study likely came to Amsterdam with the collector around 1632, or at the latest, with the presumed shipment of 1639. Years later, its composition was useful to Rembrandt and his pupil Willem Drost (1633–1657; to Italy 1655). Drost studied with Rembrandt in the late 1640s and early 1650s and seems to have been keenly interested in some of the Venetian paintings in Amsterdam.30 He portrayed a young scholar in a pose derived from that in Van Dyck’s Van Uffelen at His Desk. An etching by Thomas Worlidge of ca. 1757 (fig. 6) shows the original composition, which was then considered to be by Rembrandt.31 The basic positions of head, shoulders, and hands derive from the Van Dyck, with the suggestion of a pose between seated and rising. Van Dyck imbued his sitter with tension, with one hand, holding a compass, nervously poised upon the table and the other with fingers unfolded upon the armrest. Drost opted for calm stability, with one hand turning the pages in a book and the other resting closed upon the armrest. His young man is firmly seated, without the ambiguity of Van Uffelen’s suspended position between chair and table. Drost may have had access to the original portrait, or to an intermediary that was familiar to him from the Rembrandt workshop.

Rembrandt took Van Dyck’s half-rising pose as a solution for Volkert Jansz in the 1662 group portrait Staalmeesters (fig. 7). Rembrandt struggled for a satisfactory posture for this figure, first showing him fully seated, then standing upright.32 Van Dyck’s portrait of Van Uffelen rising from his chair provided a solution. Rembrandt’s reliance on a portrait that had evidently been in Amsterdam from the 1630s invites speculation. Did he first view Van Dyck’s Lucas van Uffelen when working on the Staalmeesters? If so it would suggest that the painting was still in an Amsterdam collection at that time. More likely, Rembrandt had long been familiar with the portrait and, when seeking a solution to the framing figure for the group gathered around the table in the Staalmeesters, he turned to it as a pragmatic guide.

Conclusion

Through the documents discussed here, a number of Italian paintings may be traced to the Godijn and Van Uffelen collections in Amsterdam. Particularly noteworthy are Godijn’s two sets of pendants by Palma Giovane and Guido Reni, and Van Uffelen’s Bassano and Reni paintings. Earlier, only one painting by each artist is documented in a Dutch collection. By 1604, Hendrick van Os owned a grand Marriage of Peleus and Thetis by Palma Giovane, according to Karel van Mander.33 By 1618, Michiel Wyntgis owned a large Judith by Reni.34 Consequently, the Palma Giovane and Reni paintings in the Godijn and Van Uffelen collections add exponentially to the number of known paintings by these artists in the north Netherlands in the early seventeenth century.

Additionally, these paintings indicate that collectors were aware of current developments in Italian painting. The art of Palma Giovane was recognized as continuing the broad brushwork and erudite mythologies of Titian, and that of Reni as continuing the classicistic direction of Raphael. Dutch artists, who, following Van Mander, recognized the validity of both approaches, could reconcile them as appropriate. Although the specifics of his contribution to Dutch painting have not yet been recognized, Reni would have been a prime example of the graceful poses and balanced palette that would have appealed to the Dutch Classicists.

Van Dyck’s portrait of Van Uffelen was familiar to Drost and Rembrandt, but we may tentatively assume that other paintings in Van Uffelen’s collection, in addition to the Castiglione, were also made known to the liefhebbers of Amsterdam through direct and indirect means. A few Amsterdam collectors publicized their art in reproductive prints. When it was owned by Alfonso Lopez, who lived in Amsterdam between 1636 and 1640 and acquired the Castiglione from the Van Uffelen sale in 1639, the painting was engraved under Sandrart’s direction, as were two renowned Titians, Ariosto and Flora.35 The Reynst paintings and ancient sculptures were systematically published in two folios of around 1655 and 1671.36 The Reynst prints, despite their availability, were not appropriated much by Dutch artists, who certainly made use of reproductive prints when it suited their purposes. How Dutch artists may have regarded the Godijn and Van Uffelen/Noirot paintings has yet to be explored, with the exceptions of the Raphael and Titian portraits.

In the aggregate, the presence of these artworks in Amsterdam collections supports Rembrandt’s oft-quoted assertion to Constantijn Huygens that some of the best paintings by Italian artists were to be seen locally and conveniently, without the bother of travelling to Italy.37 In characteristic generosity, Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann warmly welcomed me as a Columbia student into his Rembrandt seminar at Princeton in 1977. As he was commuting from New Haven and I from Manhattan, we met at Port Authority; on the bus to Princeton, we had magical conversations, about Rubens and Rembrandt and everything else. My gratitude to Egbert is profound and enduring.