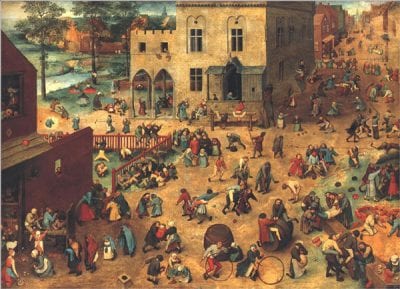

Picturing more than two hundred children playing over eighty different games, Children’s Games (1560) is one of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s most intriguing and least understood paintings. The panel resembles little else in the history of art, and as a result it has often evoked ahistorical responses. The following article addresses this problem by grounding Children’s Games in the century in which it was produced and using a range of sixteenth-century sources to develop fresh insights into how the painting might have been received by its original audience. The literature of François Rabelais, pedagogical treatises and colloquies, and Antwerp’s own progressive schooling system all provide examples of contemporary ideals about children and games that can be brought to bear on Children’s Games. After demonstrating the relevance of these sources to Bruegel’s patrons, the author uses the pedagogical literature to measure aspects of Children’s Games, resulting in a more positive reading of the panel than has hitherto been offered. This becomes particularly marked when the painting is placed alongside other sixteenth-century representations of “ideal” and “non-ideal” children.

Encountering Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Children’s Games for the first time is an experience that is both bewildering and enchanting. The painting’s large scale and unusual, encyclopedic composition render it instantly striking. Stretching to a distant horizon, the ocher ground of Children’s Games is studded with over two hundred children playing around eighty different games (fig. 1). The panel is carefully organized. A wide street sweeps from the lower left corner of the painting, encompasses the players in the central square, and extends to a distant vanishing point in the upper right. The dramatic recession of this diagonal lends the painting an asymmetric thrust, which is intersected by a second diagonal running from the beam on the ground in the lower right of the panel to the verdant countryside in the upper left. Despite these compositional structures there is no sense of narrative order to Bruegel’s collection. The game motifs are all of a similar size and events at the center of the picture appear no more charged with importance than those at its edges. This encyclopedic compositional technique is at odds with the painting’s lifelike motifs: the former encouraging the eye to move continuously over the shifting surface of the panel, and the latter prompting it to pause at each cluster of children and study the drama unfolding.

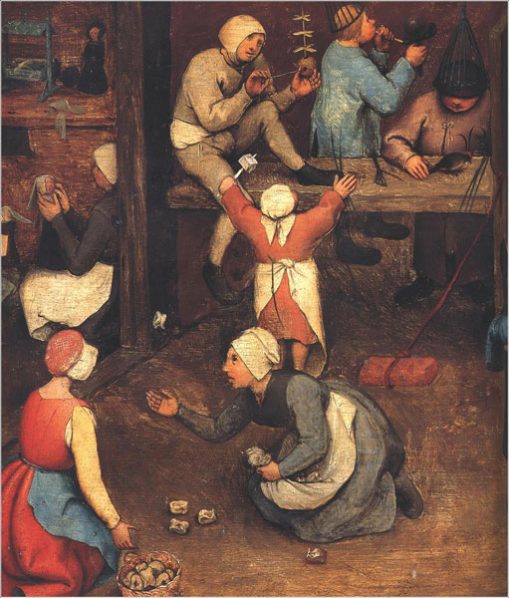

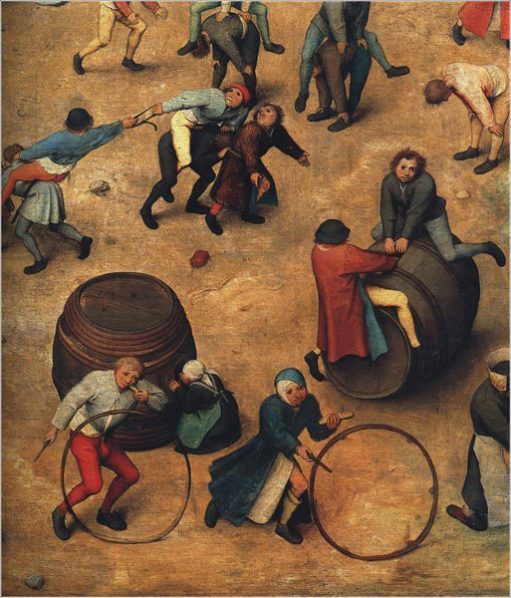

The challenge that Children’s Games presents to modern scholars operates on many levels, from the fundamental task of identifying the individual games depicted to the wider questions of the meaning behind such a panorama. The subject matter of Children’s Games is unprecedented; its only precursors being the tiny images of children playing seasonal games found in the margins of a number of Ghent-Bruges manuscripts.1 Circumstances surrounding the commissioning and evolution of the painting are unknown; no documents or preparatory sketches have come to light and the first extant reference to Children’s Games dates from the very end of the sixteenth century.2 Lacking any of the traditional aides to interpretation, scholars have adopted a variety of approaches to the painting in the centuries following its creation. The labelling and classifying of the games has been enthusiastically undertaken by folklorists, ethnographers, and historians of childhood, for whom Children’s Games represents an indispensable source in reconstructing the specifics of early modern game playing.3 A second approach to the panel has been the thematic interpretations, in which scholars have attempted to situate Children’s Games within series or allegories traditional to art history, examples being the Seasons or the Ages of Man. These attempts have been largely unsuccessful; the painting contains games which were played throughout the year and therefore resists categorization as a representation of a particular season, and no other works by Bruegel survive to support the notion that Children’s Games belonged to a series depicting the Ages of Man.4 Iconological readings represent a third type of approach.5 Here scholars seeking to “unlock” the meaning in Bruegel’s games have been drawn to comparable motifs in seventeenth-century Dutch emblems. Combining depictions of games and toys with mottos and texts that moralize about the behavior of young and old alike, Dutch emblem books appear to offer a key to understanding the deeper meaning behind images of play.6 Individual games found in emblem books such as Jacob Cats’s Silenus Alcibiabes (1618) and Pieter Roemer Visscher’s Sinnepoppen (1614) have been matched with comparable motifs in Children’s Games, with damning results: the boy blowing a bubble in the left foreground has been read as a vanitas symbol of the transience of life (fig. 2), while the games with hoops in the right foreground have been seen as representative of the futility of life’s endeavor (fig. 3).7 These moralizing iconological readings have now become dominant in the historiography of Children’s Games, despite the obvious methodological flaw in using seventeenth-century emblems to decode a sixteenth-century painting.8

Compositionally, Children’s Games resembles Bruegel’s other two encyclopedic works, Netherlandish Proverbs (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) and The Battle Between Carnival and Lent (Vienna, Kunsthistoriches Museum). Executed on panels of similar dimensions and produced in the period 1559–60, these three paintings form a distinct visual group within Bruegel’s painted oeuvre.9 Netherlandish Proverbs is peopled by errant villagers acting out popular proverbial sayings. A distant church, a river, a tavern, and a castle serve to ground the antics of the figures within the believable space of a Netherlandish village. The Battle Between Carnival and Lent takes as its theme the traditional customs and practices of the periods of Carnival and Lent and again locates its motifs within a recognizable geographical space, this time an urban square. Ruled by proverbial fools, carnival revellers, and children respectively, all three panels present worlds that are familiar but somehow upside-down, their elevated viewpoints and scurrying protagonists connecting them to the classical notion of the Theatrum Mundi, in which man’s foolish actions were contemplated from above.10 Comparisons with Netherlandish Proverbs and Carnival and Lent have often contributed to the negative interpretations of Children’s Games, but there is a more productive way to utilize this relationship. Recently, scholars have begun to engage with the question of how the encyclopedic character of Carnival and Lent and Netherlandish Proverbs might relate to their meanings. New readings of these paintings have been proposed which link Bruegel’s compositional strategies to sixteenth-century notions of abundance, or copia, and its role in rhetorical practice.11 Crucially, these interpretations acknowledge that Bruegel’s encyclopedic paintings are multivalent and resistant to the imposition of a single iconographical program; this is a fundamental assertion which accords with what is known about the viewing habits of his patrons.

While little evidence survives on the commissioning and production of Bruegel’s paintings, various inventories provide an insight into their consumption and display. Bruegel’s paintings were owned, almost exclusively, by members of Antwerp’s professional, merchant class.12 Five of Bruegel’s paintings appear in the 1572 estate inventory of the collection of Jean Noirot, a former master of the Antwerp Mint, while Bruegel’s Twelve Proverb Plates belonged to the banker Niclaes Cornelius Cheeus.13 Niclaes Jonghelinck, a businessman and government official, was Bruegel’s most enthusiastic collector; a document of 1565 lists sixteen paintings by Bruegel within Jonghelinck’s extensive art collection.14 These inventories demonstrate that Bruegel’s paintings were most often displayed in private social spaces, such as dining rooms. The inventory of Noirot’s collection records that four of his Bruegels were displayed in a room described as “d’achter eetkamerken” (small, back dining room), and it has been plausibly suggested that Jonghelinck commissioned Bruegel’s series of the labors of the Months to decorate the dining room of his suburban villa.15 Bruegel’s paintings would therefore have been enjoyed communally and by invitation only. Possessed of formal qualities that stimulated rather than resolved debates, it is likely that within these sorts of environments Bruegel’s complex panels would have functioned as conversation pieces, providing a focus for debate during gatherings of like-minded individuals.16 Van Mander’s anecdotes on Netherlandish painters support this idea; his stories of viewers searching for motifs such as a little owl in the works of Herri Met de Bles or a “little shitter” in the landscapes of Patinir are evocative of a culture in which looking was an active, and, for some, competitive sport.17

By focusing on sixteenth-century sources and patterns of response this article seeks to challenge the common assumption that the historical context of Children’s Games yields “neither a unified period consciousness nor a stable set of sixteenth-century ‘beliefs’” by recovering the kinds of arguments that the painting might have elicited among its original audience.18 In fact, by the mid-sixteenth century a rich seam of debate existed about children’s conduct, education and play– subjects that were discussed repeatedly in the countless number of pedagogical texts produced by the century’s humanist educators. As the center of the European printing trade in the first half of the sixteenth century, the city of Antwerp naturally provided a nexus for the production and exchange of pedagogical texts. Furthermore, for a variety of economic and social reasons sixteenth-century Antwerp possessed a particularly progressive educational character. This meant that the city’s inhabitants were actively involved in producing texts and shaping pedagogical theory and practice, providing a direct link between Bruegel’s clientele and the kinds of ideas outlined in the texts.

Few scholars have explored the potential links between Children’s Games, Renaissance humanists, and educational reform; that is, until the recent book by Margaret Sullivan.19 Noting the status of Children’s Games as a collection, and comparing the painting’s inception to that of Netherlandish Proverbs, Sullivan describes how: “observing children in the present and culling references to them in the past was an entertaining and appropriate way to spend leisure hours in the sixteenth century.”20 Sullivan’s treatment of the humanist literature in relation to Children’s Games focuses on examples where the games discussed can be traced back to ancient Latin and Greek sources, and, like previous iconological readings of the painting, it is broadly moralizing in tone.21

My article differs from this approach in several ways. Firstly, additional sixteenth-century sources are considered, including pedagogical texts by such authors as Maturin Cordier and Gabriel Meurier and fictional texts, by such authors as François Rabelais. Secondly, by focusing on the educational situation in Antwerp I demonstrate how the city’s schools provide a direct link between sixteenth-century pedagogical ideas and Bruegel’s clientele. Finally, by using the period’s pedagogical texts to measure aspects of Children’s Games I argue that Bruegel’s original viewers might have interpreted the panel more positively than we do today. This last contention becomes particularly marked when the painting is placed alongside other sixteenth-century representations of “ideal” and “non-ideal” children.

Gargantua’s Games

The writings of François Rabelais provide a useful starting point when establishing sixteenth-century attitudes toward children, games, and encyclopedic collecting habits. Perhaps the best comparator to Bruegel’s panel is the list of over two hundred games which fill chapter 22 of Rabelais’s mock-heroic tale Gargantua.22 Near contemporaries, both Bruegel and Rabelais were intrigued by those aspects of popular culture about which little hard evidence survives and both employed a similarly effusive style of presentation. The pair were even linked during the sixteenth century when Bruegelian imagery was used to illustrate a collection of woodcuts marketed under the Rabelaisian title Les Songes Drolatiques du Pantagruel (The Droll Dreams of Pantagruel) (1565).23 Although using Rabelais to elucidate arguments about Bruegel is hardly new, paying close attention to Gargantua’s games can enrich our understanding of Children’s Games in significant ways.24 Rabelais’s prose has often foreshadowed events that were later pictured by Bruegel, with all three of Bruegel’s encyclopedic paintings finding their equal within Rabelais’s texts.25 Of these, the parallels between Children’s Games and the list of games played by Gargantua are the most compelling, and Rabelais’s list has been described as a “direct precursor” to Bruegel’s panel.26 While new evidence discussed below highlights the availability of Rabelais’s texts in Antwerp at the time that Bruegel was creating his paintings, my argument is not one of direct influence and quotation, but more of the kinds of “habits of mind” evidenced by both the content and presentation of the two game lists.27

The question of when Rabelais’s texts became widely available in the Netherlands has never been answered conclusively.28 However, evidence contained in the archives of the Plantin Moretus Museum confirms that Rabelais’s books were circulating in Antwerp by the middle of the sixteenth century. Christopher Plantin was a Frenchman who settled in Antwerp around 1549 and quickly rose through the ranks from bookseller to bookbinder and then to publisher, establishing De Gulden Passer (The Golden Compasses) publishing house in 1555.29 Plantin’s French origins make him a logical link to Rabelais: when accused of heresy in 1562 Plantin fled to Paris for two years, and later in the decade the printer even established a branch of his firm in the French capital. Throughout his lifetime Plantin retained close business relations with France, with the number of texts he published in French almost equalling those published in Dutch.30 French was second only to Flemish as the most used language in the Netherlands, and records suggest that Plantin also relied heavily on French imports for income, with French texts accounting for almost half of Plantin’s total purchases in 1566.31 Bibliographies of the output of the Plantin Press do not list Rabelais among those authors published by Plantin in the Netherlands.32 However, several of Plantin’s handwritten journals include references to works by Rabelais, suggesting that they were among the French books that the printer imported from his Parisian associates.

Plantin took most of his journals with him when he fled to Paris and thus few records of his early trading survive. One exception is a journal kept between the years 1558 and 1561.33 This volume records the titles of books that passed through Plantin’s Antwerp shop in the left margin alongside the names of other booksellers and dealers active in the Netherlands (Plantin’s clients) in the right margin. Included frequently among the titles listed in this journal are the words “Rabelais” and “Pantagruel.”34 According to the handwritten entries, the titles were supplied to a number of Netherlandish booksellers, including Pierre de la Tombe in Brussels, Vincent de la Vacquerie and Jourdain Gravioule (Jourdain de Granville) in Liège, and the veuve Pissart in Ath.35 A later journal from 1566 again includes “Rabelais” and “Pantagruel” among its list of titles, suggesting that Plantin continued this trade for some time.36 It is not hard to imagine how Plantin obtained these works; while no records of his buying habits survive from this period, Plantin’s large network of Parisian contacts included printers with links to Rabelais, such as Arnoul L’Angelier and the Marnef family.37

Comparisons between the work of Bruegel and Rabelais are legitimized by the discovery that Rabelais’s books were being handled by Christopher Plantin. Plantin is known to have traded in Bruegel’s prints, but perhaps more importantly he was a member of the circle of educated Antwerp humanists who have often been linked to Bruegel. Plantin maintained a close relationship with Bruegel’s chief print-publisher, Hieronymous Cock.38 He was also close to the geographer Abraham Ortelius, whose Album Amicorum (Friendship Album) contains a moving epitaph to Bruegel in which the artist is described as a friend.39 These kinds of erudite men were precisely the clientele who would have been intrigued by the “listing” style employed by both Rabelais and Bruegel in their enumerations of games. Cock pioneered the practice of issuing prints in related sets or series, while Ortelius was an enthusiastic list maker in his own works.40 The fictional game lists produced by Bruegel and Rabelais should thus be understood as symptomatic of a wider trend, an abundant aesthetic which typified many sixteenth-century works.

There are important formal and iconographic similarities between Children’s Games and Gargantua’s games, but the focus of this article is on the broader pedagogical context within which Gargantua’s game list has been understood. Gargantua’s games come at a key point in Rabelais’s narrative, when the eponymous hero is growing up. Beginning his education under a variety of unremarkable tutors, Gargantua learns little except how to write in the outmoded Gothic style. After meeting with the model pupil Eudémon, Gargantua’s father decides instead to send his son to Paris to receive a humanist education from Eudémon’s tutor, Ponocrates. Ponocrates starts by inviting Gargantua to demonstrate his old ways, and it is here that the largest exposition of games ensues (chapter 22). In subsequent chapters Ponocrates takes charge, prescribing a new regime in which no hour of the day is wasted: Gargantua duly grows wise and strong (chapter 23 and 24). Rabelais’s presentation of these two antithetical educational methods–sophist and humanist–and the eventual triumph of the humanistic approach have been understood as an endorsement of the new humanist pedagogy espoused in numerous treatises, statutes, and school colloquies.41 What is particularly interesting about this text in relation to Bruegel’s panel is the value placed on games throughout Gargantua’s education. While the best-known game list occurs in chapter 22, when Gargantua is “misbehaving” by following old methods, games are in no way excluded from the later chapters detailing Gargantua’s virtuous humanist upbringing. The types of games and the manner of playing changes, but the overall prevalence of games and delight in play remains the same; the fundamental role of games in Gargantua’s fictional maturation and education reflecting what were very real, factual concerns of the period.

Play and the Humanist Educators

If the emblem books of the seventeenth century used children’s games to symbolize the weaknesses of mankind, then the dozens of pedagogical texts published during the course of the sixteenth century presented the opposite view. In the century in which Children’s Games was created, game playing was widely recognized as a vital component of childhood and a positive force on many levels, a view epitomized by Erasmus in his statement: “I’m not sure anything is learned better than what is learned as a game.”42 The humanist educators wanted to encourage children to love learning, and they knew that this would not be achieved if students were compelled to fill every hour of the day with study. Recreational breaks to refresh the mind were thus recognized as a necessity, and games represented the ideal form of respite. Classical authors had stressed the role of sports and games in developing a young warrior’s strength and dexterity, and these recommendations were revived and adopted by the humanist pedagogues who detailed the physical benefits of game playing. In addition to providing fitting respite from academic studies and promoting physical vitality, play was also valued for the wider lessons it taught about life. According to Erasmus boys’ characters were nowhere more apparent than in a game, and it was widely felt that lessons on compromise, moderation, and the vicissitudes of fortune could all be learned through play. It is worth briefly surveying these attitudes in the major sources before addressing the specific situation in Antwerp.

One of the earliest works to discuss the raising of children in any detail was Erasmus’s 1511 text De ratione studii (Upon the Right Method of Study).43 Advancing a new humanist curriculum through its emphasis on rhetoric and classical literature, the De rationii studii also addressed themes such as the importance of childhood as a time to develop virtuous habits and the duty of parents and schoolmasters to be gentle but firm. This was followed in 1530 by the De civilitate morum puerilium (On Good Manners for Boys), a work which detailed aspects of children’s manners, behavior, and dress in a variety of situations, including when at play.44 Erasmus’s manual was immediately popular in schools, where it was read both for its useful advice on decorum and for its elegant grammatical style.45 A portrait attributed to Maerten van Heemskerck provides evidence that the ideas contained within these texts had permeated Bruegel’s artistic environment by the middle decades of the sixteenth century (fig. 4).46 Dated just a year after the publication of the De civilitate, Heemskerck’s Twelve-Year-Old Boy presents the visual realization of an Erasmian ideal. Poised with a quill pen in his right hand and paper in his left, Heemskerck’s sitter displays all of the desirable aspects of comportment described in Erasmus’s text: he is neatly dressed in a black doublet and red cap, his hair is combed and cut straight, and he has a calm facial expression. Inscriptions found within the image provide an even more direct link to Erasmian philosophy. The Latin hexameter printed on the parapet comes from Erasmus’s Opuscula aliquot, a collection of ancient sayings which was expressly aimed at schoolchildren and reprinted forty times between 1514 and 1531.47

Even more important and influential sources for Rabelais were the writings of the Spanish humanist educator Juan Luis Vives, whose largest work was the twenty-book De tradendis disciplinis (On the Transmission of Knowledge), published in Antwerp in 1531.48 As with Erasmus, games played an important part in Vives’s educational philosophy. De tradendis describes game playing as an important respite from study, while the Introductio ad sapientiam (Introduction to Wisdom) suggests playing quiet games after supper.49 In these formal treatises games can be understood as occupying a supporting role by rounding out the program of academic study, but in the numerous school colloquies produced by the same authors play took center stage, with the most widely published examples being Erasmus’s Familiarum colloquiorm formulae (Basel, 1518), Vives’s Linguae latina exercitatio (Breda,1538), and Maturin Cordier’s Colloquiorum scholasticorum (Geneva, 1564).50 Virtually the only works of contemporary authorship to be admitted into the curriculum of sixteenth-century grammar schools, colloquies took the form of imaginary dialogues between masters and pupils or between groups of pupils. In an attempt to engage young minds, conversations focus on the everyday subjects that would have been familiar to schoolboys: characters walk to school together, argue about which games to play at mid-morning break, request extra play time from their tutors, and then return home to play more games. Some colloquies describe a day in the life of a student, including discussing when and where games might be appropriate, while others speculate upon the origins, rules, benefits, and pitfalls of specific games.Like popular proverbs, the colloquies weave moralizing lessons into everyday life; the hope being that they would mold young minds, and inculcate high moral standards as well as a proficiency in Latin. While the colloquies of Erasmus, Vives, and Cordier represent the best-known examples of the period, numerous other treatises and colloquies that discussed games emerged throughout the course of the century.51 Cordier’s treatise on the reform of Latin teaching, the De corrupti sermonis emendatione (Paris, 1530) presented phrases for schoolboys in French and Latin and included a chapter devoted to phrases used in playing games.52 Lists of appropriate games and pastimes can also be found in gentlemen’s handbooks such as Baldassare Castiglione’s Il Libro del Cortegiano (Venice, 1528) and Thomas Elyot’s Boke named the Gouernour (1531).53 Roger Ascham’s Toxophilus (1545) defended archery as a pastime and recommended it most particularly to scholars, who should take it as an antidote to their sedentary lifestyles, while his treatise The Scholemaster (1570) encouraged young scholars to indulge in “courtly exercises and gentlemanlike pastimes,” including games.54 Finally, one of the century’s longest discussions of appropriate games and pastimes can be found in chapters six to thirty-five of Richard Mulcaster’s Positions Concerning the Training Up of Children (1581).55

Pedagogical Images and Texts in Antwerp

The important place afforded to games by the humanist educators suggests that pedagogical debates may be relevant to understanding Children’s Games. With their detailed descriptions of the specifics of game playing school colloquies can provide insights into Bruegel’s iconography, while broader issues concerning aspects of the painting’s patronage and reception can also be explored through an educational lens. These arguments can be further localized within Bruegel’s home city of Antwerp. As the center of the European printing trade during the first half of the sixteenth century Antwerp’s presses were engaged in printing many of the period’s most influential educational texts, including the major works by Erasmus, Vives, and Cordier.56 Furthermore, Antwerp’s strong economic position led to the development of a uniquely flexible and progressive schooling system. Within this system, the theories forwarded in the major texts could easily be put into practice, and a host of more minor, localized pedagogical texts emerged, which can be directly linked to members of Bruegel’s social network. In addition to the texts, a variety of images produced in the Netherlands in the middle decades of the sixteenth century attest to a growing interest in children’s activities.

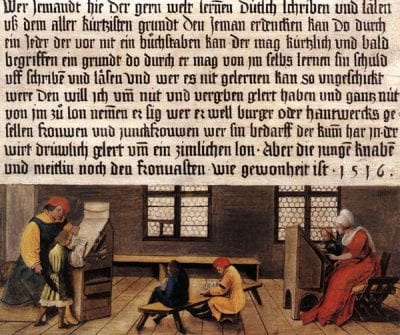

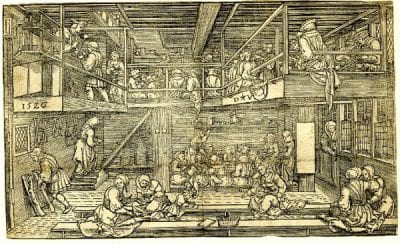

Beyond the realms of portraiture, paintings of children were still unusual in the sixteenth century; if they were represented at all children more usually appeared in woodcuts, prints, or illuminated manuscripts. These images are often polarized between idealized representations of children studying diligently and errant children misbehaving. Produced early in the century as an advertisement for a teacher’s services, Hans and Ambrosius Holbein’s double-sided Signboard for a Schoolmaster depicts adult pupils being taught to write on one side and younger pupils at work with a schoolmaster and schoolmistress on the other (fig. 5). Dirk Vellert’s Schoolroom woodcut, published in Antwerp and dated 1526, again pictures groups of figures at work inside a schoolroom, with a schoolmaster seated prominently in the upper left of the image (fig. 6).

Bruegel’s own printed oeuvre contains examples of both positive and negative depictions of learning. These include the cluster of students at work in the foreground of Temperantia (Temperance) from the series of Seven Virtues (fig. 7) and the satirical depiction of an unruly schoolroom in the Ass in School (fig. 8).57 The original drawings for both of these prints survive: signed and dated 1560 and 1556 respectively, they suggest that Bruegel was engaged with the debates about pedagogical practice in the years immediately preceding the creation of Children’s Games. Representing Grammar, the ten pupils in the Temperantia group are neatly dressed and engrossed in their books. The students cluster beside the schoolmaster, who is seated with a paddle in his hand, a rod tucked into his belt, and a pen case and inkwell hanging from his belt. One pupil appears to be receiving instruction or reciting a lesson, as he stands at the master’s knee and diligently points at an alphabet board. The Ass in School is also filled with the educational paraphernalia of hornbooks and ABC’s, but here they are not put to good use. Instead of being studied, the texts are held up or thrust forward toward the viewer, as though for ridicule, while the pupils squat, pull faces, expose themselves, and hide under hats, their actions recalling a variety of contemporary proverbs with negative associations. Instead of benignly regarding the class, the schoolmaster in the Ass in School has his hand raised to the bare backside of one member of the group, his actions betraying the humanist educators who strongly opposed such measures.58 An ass, which stands on its hind legs at the open window, completes the ridiculous classroom and embodies the metaphor of the “unteachable” student. The sheet of music, eyeglasses, and a candle arranged on the window ledge serve to demonstrate the animal’s foolish pretensions to learning, and the moral message is further underlined in the inscription below, which reports that even with the help of these props the ass will be unable to utter anything but its characteristic braying sound.59

Fusing the animal symbolism of medieval ape schools with a new kind of peasant satire, the Ass in School is often seen as a founding image in the “unruly schoolroom” genre which was to be developed in the seventeenth century by artists such as Adriaen van Ostade, Adriaen Brouwer, and Jan Steen.60 More contemporary to Children’s Games, and also influenced by the Ass in School, is a satirical print published by Bartolomeus de Mompere and attributed to Pieter van der Borcht known as The Cobbler and His Wife as a Teacher (fig. 9).61 Like the Ass in School, the Cobbler and His Wife derives its satire from exaggerating the poor behavior of children. The central figures of the cobbler and his wife are shown frantically trying to repair a shoe and spinning while all around them children misbehave. The cobbler’s weariness is confirmed by the inscription in French and Flemish below which reads: “I mend, I sew, I stitch many a seam, but whatever I do I get nowhere / It is bitter to earn a living because these children give me headache and no profit.”62 The inscription suggests that the print presents an over-grown family group. In the seventeenth century, however, a reversed copy of the Cobbler and His Wife was published by Pieter Bailleu and titled Allemode School, indicating that the image also fit the contemporary taste for exaggerated, unruly schoolroom scenes.

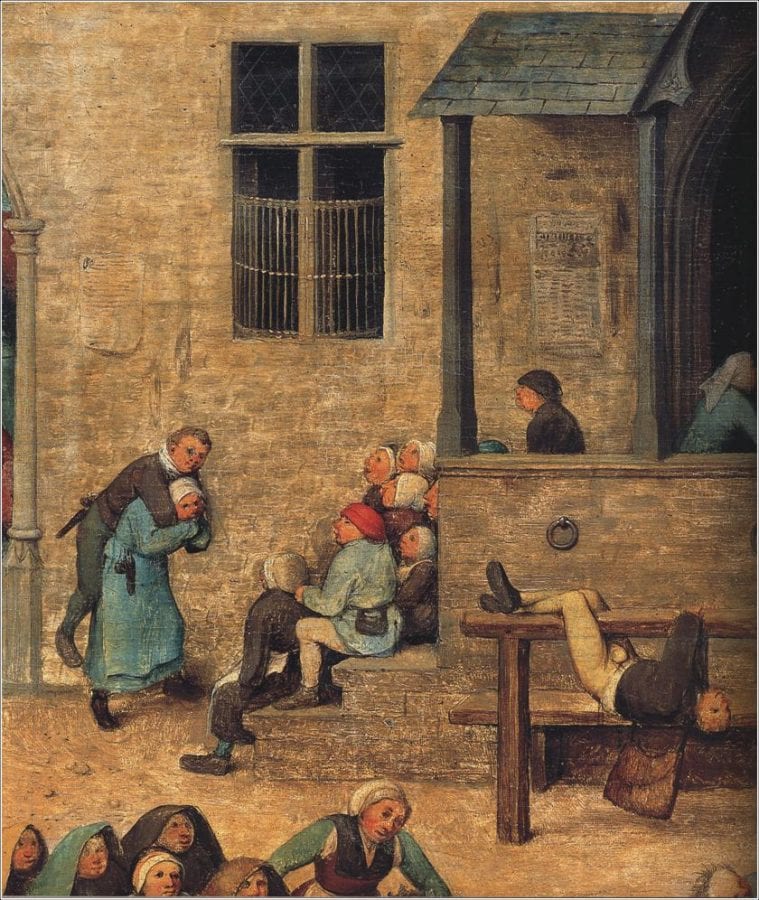

To these images of children can be added a number of paintings more directly related to Children’s Games. Today, there are no extant copies of Bruegel’s panel, giving the false impression that Children’s Games was an esoteric one-off. In fact, it is likely that a number of copies of the work were produced by Bruegel’s son, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, in the later decades of the century and are now lost. Two such compositions are listed in the 1614 estate inventory of the Antwerp art dealer Philips van Valckenisse.63 A little-known composition by Maerten van Cleve provides further evidence for the dissemination of Bruegel’s idea in panel painting and also supports the argument that Bruegel’s contemporaries might have understood Children’s Games in pedagogical terms. Dateable to the 1560s, Van Cleve’s Children’s Games closely resembles Bruegel’s composition, and was similarly popular–it survives today in four versions (fig. 10).64 Van Cleve’s panel lacks the skillful panoramic perspective found in the earlier work but mimics many other compositional devices employed by Bruegel. The children’s games take place in a square which is intersected by the diagonal thrust of a beam in the foreground and a receding street in the background. Thatched roofs and trees appear in the left background, and a large structure marks the rear of the square (here a church but in Bruegel’s panel a civic building). Despite this, there are some notable differences between the two compositions. The figures are larger in Van Cleve’s work, and the perspective less steeply raked, meaning that a far smaller selection of games is presented. Van Cleve also included some additional games which are not pictured by Bruegel; the games of see-saw and pet en guelle (see below) in the right foreground, which appear in other works by Bruegel but are absent from Children’s Games, being examples of this. A final difference is a detail found in the left foreground of Van Cleve’s painting, where a wide doorway, recalling that found in Bruegel’s Children’s Games, frames the figure of a schoolmaster. This figure can be identified as a schoolmaster by his clothing and his attributes: he wears the black hat and long robe of a scholar over a white shirt and black jerkin and holds a scroll in his right hand (examination suggests that a line resembling a rod originally appeared in his left hand but was later painted out). Watching the children play, the schoolmaster displays an impassive face, so that it is difficult to determine whether a moral message is intended. Nonetheless, the inclusion of this figure is significant in relation to Bruegel’s painting, as the schoolmaster makes a contemporary connection between a panorama of play and the paraphernalia of learning.

While the images presented above indicate that the humanistic interest in education had begun to affect artistic production by the middle of the sixteenth century, it is Antwerp’s network of free schools that provides the link between the pedagogical texts and Bruegel’s circle of known patrons and associates. Travelling through the Low Countries in the sixteenth century, the Italian writer and historian Ludovico Guicciardini was awed by the levels of literacy that he encountered, an observation that has been supported by generations of scholars.65 Published in 1567, Guicciardini’s famous account of the Netherlands, the Descrittione di tutti i Paesi Bassi (Description of the Low Countries), includes an illuminating passage on Antwerp’s distinctive educational system:

‘Here [in Antwerp] there are many schools with learned masters to instruct youth in all kinds of skill in letters…But in this city and in the whole country it is a common custom, once the children have made a good beginning, and it is desired to let them continue their studies, to send them to France, Germany and Italy. In this city, as in many other cities of the country, there are also several schools where both girls and boys learn the French language…and moreover there are masters here who teach Spanish and Italian, from which it appears in all ways that this city is the common fatherland of all Christian nations and will remain so, if it does not alter its form and essence.’66

Guicciardini’s account highlights what made Antwerp’s educational system unique. Although Antwerp lacked a university, it was not short of options for secondary education, which was available in the city from any number of ‘learned masters’. Like all towns in the Netherlands, Antwerp possessed a number of official church schools where Latin was taught.67 In theory these institutions should have had a monopoly on secondary education, but in practice Antwerp’s large middle class often placed their children in privately run free schools, which were regulated from 1530 onward by the Guild of St. Ambrose.68 The absence of any nuns or monks from Vellert’s Schoolroom suggests that the woodcut may depict one such free school; the image is known in only one impression, and it has a vertical fold down the center, indicating that it may once have been bound or pressed in an educational book.69 A free school could be opened by any citizen of either sex and the curriculums of such schools naturally reflected the personal skills and abilities of the particular teacher, making them far more idiosyncratic and experimental than the traditional church schools. In a commercial metropolis like Antwerp, the emphasis inevitably fell on developing skills that would be useful for the aspiring merchant, including vernacular languages such as French, German, Italian, and English and the formal instruction of bookkeeping. Regulations surrounding the teaching of Latin, which had originally been forbidden in free schools, were evidently relaxed during the sixteenth century as many of Antwerp’s free schools offered instruction in Latin and Greek in addition to vernacular languages.70 Surviving records from the Guild of St. Ambrose record a rapid expansion in the number of free schoolmasters working in the city in the mid-sixteenth century, with the number doubling between 1530 and 1562 as Antwerp’s network of private schools grew.71

One of Antwerp’s most successful free schools was De Lauwerboom (The Laurel Tree), an all-girls school, which was founded by Peeter Heyns in 1555. A factor (author) for the Berchem Chamber of Rhetoricians, Heyns belonged to the circle of Antwerp humanists often associated with Bruegel. Heyns and two of his six children (Catharina and Zacharias) feature in Abraham Ortelius’s Album Amicorum, and Heyns worked with Philips Galle to create a pocket version of Ortelius’s famous atlas, known as the Spiegel der Werelt.72 Heyns was also close to Christopher Plantin; he produced and translated various educational texts which were published by Plantin, and the printer dedicated an edition of Vives’s De institutione feminae Christianae to Heyns.73 It is not surprising to find that the latest pedagogical ideas were current among Bruegel’s learned associates. Noting the number of humanist texts that discuss games, Margaret Sullivan recently speculated that the patron of Children’s Games may have been someone with a specific interest in the behavior of children, perhaps an educator.74 However, evidence from De Lauwerboom school serves to widen the application of these texts, suggesting that the latest pedagogical theories on games might also have been commonplace within the families of Bruegel’s mercantile patrons. The register of pupils at De Lauwerboom for the years 1576–84 is preserved in the Plantin-Moretus Museum.75 Even though the dates are late in relation to Children’s Games, the register suggests the kind of clientele that the progressive school attracted in the mid-sixteenth century. Among the pupils listed are “Josyne ende Maeyken Galle,” daughters of the engraver Philips Galle, and “Anneken Jonghelings,” daughter of the sculptor and medalist Jacques Jonghelinck, who was the brother of Bruegel’s greatest patron, Niclaes Jonghelinck. Other notable pupils at the Lauwerboom included the daughters of the merchant Gillis Hooftman and the printer Willem Silvius.

The period’s major pedagogical texts would have featured prominently in the curriculum of free schools like De Lauwerboom: Peeter Heyns was responsible for translating the Colloquies and Adages of Erasmus into French and Flemish, while another Antwerp schoolmaster, Josse Verrebroeck, translated works by Erasmus and dialogues from Peter Schade’s Paedologia to help his students learn Greek.76 In addition to this, a proportion of Antwerp’s free schoolmasters were involved in authoring their own pedagogical texts. The importance of languages in cosmopolitan Antwerp meant that the needs of adult merchants rather than schoolchildren were often the focus of colloquies and dictionaries. But there were some exceptions to this. The title page of a children’s ABC book, written by Heyns and published by Plantin in 1568, is decorated with playing putti, recalling both the classical world and contemporary associations between play and learning.77 The schoolmaster Gabriel Meurier produced a large number of texts concerned with language teaching, some of which were aimed specifically at schoolchildren.78 His work in French and Flemish La Guirlande des jeunes filles/Het Cransken der jonghe dochters (1564) describes the daily life of young girls attending a school based in a middle-class home and includes two poems at the end, one for “Pierre Heyns, amateur et digne professor du François” and the other “Au college des nymphes du Laurier,” suggesting that it was produced specifically for Heyns’s school.79 Arranged in two columns, the text presents dialogues between girls and their schoolmistress as the girls learn how to run a home, entertain, and correspond with their families. Reflecting the intake of De Lauwerboom, the students generally hail from middle-class backgrounds: they are the daughters of merchants and artisans. Full of details and colorful characters, the dialogues are both humorous and didactic, and in this sense are directly comparable to Bruegel’s detailed scenes of sixteenth-century life.

Picturing Children: Bruegel’s Children’s Games and Sixteenth-Century Ideals

Lacking information on the specific circumstances surrounding the commissioning of Children’s Games, we can only surmise that the painting would have been enjoyed by the kinds of mercantile, upwardly mobile viewers linked to Bruegel’s other works. With the situation in mid-century Antwerp in mind, we can imagine that the latest pedagogical ideas would have been firmly embedded in the heads of these viewers, who educated their children in the new humanistic free schools and relied on colloquies and dictionaries to carry out their daily business. Taken collectively, the pedagogical texts and images outlined above describe the kinds of opinions that these viewers would have held on children, games, and play. As such they provide an important contextual frame for Children’s Games and can be used to explore various aspects of Bruegel’s panel, including the time and place of the children’s games, the types of games that are being played, and the manner in which play is undertaken.

The humanist educators encouraged outdoor play all year round, but physical play peaked during the summer months. This was due to a combination of a greater number of holidays and better weather, a bias reflected in the school colloquies, where pupils frequently make mention of the fine weather as justification for being outside playing.80 The weather depicted in Bruegel’s painting is certainly the sort that would call children to play. The blue sky, fading to gold in the upper left corner, indicates that the season is summer. The casual manner in which the children linger in the river also suggests that the day is hot, and that the river is a cool and pleasant place to chat. When fine weather ensued, the optimum location for play was considered to be outdoors, in the suburbs or countryside adjacent to the city. The schoolmaster in Erasmus’s colloquy De lusu (Sport) permits the boys to play only if they are together in the fields and return before sunset, and Gargantua similarly accompanies his humanist tutor Ponocrates into the countryside to relax, fish, and explore. In the Gouernour, Elyot described how the Romans set aside a large field outside of the city where the youth could exercise, called the Campus Martinus.81 The field adjoined the river Tiber, enabling men and children to refresh themselves after their labors and also learn to swim. Fresh air, firm (but not hard) ground, and shelter from the wind were also important prerequisites for Richard Mucalster when he described the ideal location for games in his Positions Concerning the Training Up of Children.82 Children’s Games broadly corresponds to this advice, with the games taking place in a composite–and probably imaginary–outdoor space, which references both the urban and the rural. While the backdrop for the games contains some architectural details that are reminiscent of Antwerp, Bruegel seems to have been less interested in faithfully rendering his home city than in creating a space that facilitated a great variety of play: the urban furniture of doorways, porches, and walls providing obstacles for the children to run up, hang off, and spin counters against.83 The urban street on the right is juxtaposed with a rural idyll in the upper left which is quite unlike anything that would have been found within Antwerp’s city walls. The stream, grass, trees, and half-timbered houses pictured here are visually incongruous but certainly accord with sixteenth-century ideals. Recalling Elyot’s description of the Campus Martinus, this section of the panel demonstrates that the children are not contained but are free to wander and explore a variety of different environments and to play outside of the constraints of the city. In addition, the area of verdant countryside provides a suitable place to depict ancient activities like tree climbing and swimming, which were recommended by the humanists in the sixteenth century for developing physical strength and dexterity.

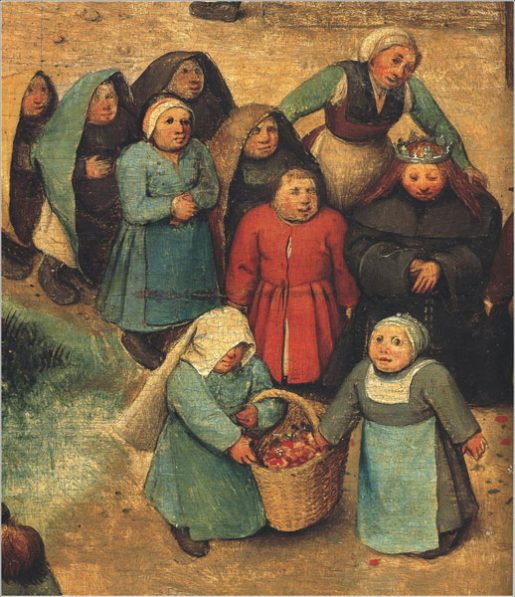

Within the school colloquies feast days and holidays are typically cited as a justification for game playing, and a number of details in Children’s Games are suggestive of such occasions.84 The painting has traditionally been interpreted as a representation of midsummer festivities, evidenced by the summery weather and the various activities that occur around the bonfire in the street on the right.85 However, it is important to acknowledge that Children’s Games does not depict these summer festivals unequivocally or exclusively, as Bruegel’s painting also includes details from midwinter and springtime festivities. The mock-marriage procession found near the centre of Children’s Games has often been read moralistically as a comment on adult affairs (fig. 13).86 However, details such as the crown worn by the bride and the basket of flowers carried by her attendants can equally be seen in relation to the numerous Whitsun processions found decorating the month of May in Ghent-Bruges books of hours.87 Three children in the panel wear the crude painted paper crowns that were made for the winter festivals of Carnival and Epiphany. One of these children also holds a distinctive duivekater loaf, a type of bread which was baked during the holiday season between the Feast of Saint Nicolas (December 6) and Epiphany (January 6), and which is frequently included by artists in depictions of ‘midwinter’.88 In short, the festive aspects of Children’s Games are both more diverse and more specifically tied to the culture of children than has previously been acknowledged. The panel does not depict a single festive moment like Bruegel’s later panels The Peasant Dance and Peasant Wedding (both Vienna, Kunsthistoriches Museum) but should instead by understood as an encyclopedic representation of games and festive traditions drawn from children’s culture throughout the year.

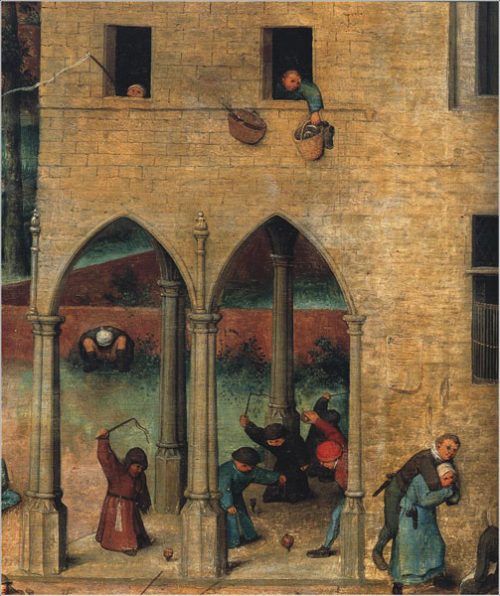

While the outdoor location and festive motifs detailed in Children’s Games reflect humanistic ideals regarding leisure time, the lack of a clear educational context for the children’s games is more contentious. The humanist educators regarded play chiefly in the context of the broader curriculum; in one of Vives’s colloquies, titled Leges ludi (Laws of Play), a character states unequivocally “Man is constituted for serious affairs, not for frivolity and recreation. But we are to resort to games for the refreshing of our minds from serious pursuits. The time, therefore, for recreation is when the mind or body has become wearied.”89 The influence of Vives can be felt in Gargantua’s humanistic regime, which includes regular breaks for play; the same careful balance is also found in the colloquies of Erasmus and Cordier.90 At first glance, Children’s Games would appear to defy this recommendation, for it contains no evidence of hornbooks or ABC-books to balance out the games. Either of the buildings bordering the central square may be schoolhouses, but without the presence of the schoolmaster found in van Cleve’s painting this is impossible to determine. The “wise” owl perched beside the entrance to the building in the left foreground may have evoked learning for Bruegel’s contemporaries, but the complex symbolism of owls in prints by Bruegel cautions against a straightforward reading of this detail.91 However, close inspection of the area around the central civic building reveals a number of details that might be interpreted with more certainty as ‘educational paraphernalia’.

Traditionally identified as Saint Nicolas baskets, it could be argued that the baskets hanging from the two windows above the loggia may be ‘school baskets’ of a type described by Willemsen (fig. 11).92 Made from reeds and often fitted with closing lids, these baskets were probably used for carrying equipment to and from school. They appear in a number of schoolroom interiors; one sits on the bench in the foreground of Vellert’s Schoolroom (fig. 6) and more can be found both on the floor and hanging from the walls in the Ass In School (fig. 8). This identification is supported by the fact that the basket on the left in Children’s Games appears to contain a ‘rod’ – a bundle of twigs (usually birch) that was used for disciplining pupils. The traditional attribute of teachers, rods had been ubiquitous in school scenes and allegories of Grammar since medieval times; one is tucked into the belt of the schoolmaster in Temperantia, while two rods are required for the unruly class in the Ass in School (one is placed prominently in the schoolmasters hat, another sits in a pot nearby).93 On the ground directly below the baskets in Children’s Games the children sport more evidence of learning (fig. 12). A boy hanging upside-down from a beam wears a brown schoolbag slung across his body, its distinctive design of a long strap and fold-over flap corresponding to that of other representations of sixteenth-century schoolbags, including the schoolbag worn by a student in Temperantia. A final link to educational activities is suggested by the writing cases that hang from the belts of at least five of the players in Children’s Games. Double writing cases of the type shown in the painting consisted of a pen case and inkwell and were usually made from leather. They are visible hanging from the belts of the girl and boy engaged in a piggy-back in front of the civic building, the boy in blue bent over in the tug-of-war, one of the boys playing ‘blind shoe’ towards the upper left of the painting and on the belt of the boy seated on the beam for the game of ‘bucca’. Like schoolbags and rods, writing cases were frequently employed to connote the schoolroom in manuscripts and prints; they can also been found, for example, in Temperantia, where a pen case and inkwell hang from the belts of both the master and the pupil reciting his alphabet.94 An image of an eight year old boy wearing both a schoolbag and a writing case whilst at play appears in a folio depicting ‘Games played in the schoolyard’ in the Trachtenbuch (Costume book) of Veit Konrad Schwarz (Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, ms H. 27, no. 51). Picturing schoolyard antics at the Latin school in Augsburg, c.1550, the selection of games, urban setting and clothes worn by Veit in this colourful folio all recall Children’s Games.95 As with so many of the details in the encyclopaedic panels, Bruegel’s employment of educational paraphernalia in Children’s Games is tentative and its significance remains open to debate. Bruegel’s painted oeuvre includes many depictions of children, but writing cases and schoolbags do not feature in any of these other paintings; a penknife hangs from the belt of the boy in the foreground of the Peasant Wedding, while the two girls in the foreground of The Peasant Dance sport a purse and a bell. The writing cases and schoolbags visible among the toys and games in Children’s Games may have been passed over by contemporary viewers, dismissed as typical attributes of childhood; but it is equally possible that they were sought out, providing reassuring evidence that learning was not far away.

Children’s Games may not contain a schoolmaster, but it does contain at least six adult figures who facilitate the children’s play. These figures are spaced across the panel: on the left they include the woman who throws a blue cloak over the group of children by the loggia and the woman who shepherds the Whitsun bride (fig. 13). In the street to the right a woman leans from a window to throw a pail of water over two wrestling boys, and farther away a man carries a child on his shoulders. In the foreground is a particularly touching trio as a man and woman “swing” a little girl in red, their tender expressions suggesting that they may be her parents (fig. 14). For sixteenth-century viewers, these figures would have been an important means of legitimizing the children’s games. Vives described how games should take place under “the eyes of older people,” Ponocrates oversees Gargantua’s leisure time, and the school colloquies repeatedly describe the role of schoolmasters in granting permission for games.96 In Cordier’s colloquies this role is also extended to parents when a father’s travels provide occasion for him to discuss how “dissolute boys” may take advantage of their father’s absence to drink, play, and run about, but a good boy “lives in his father’s absence as in his presence.”97

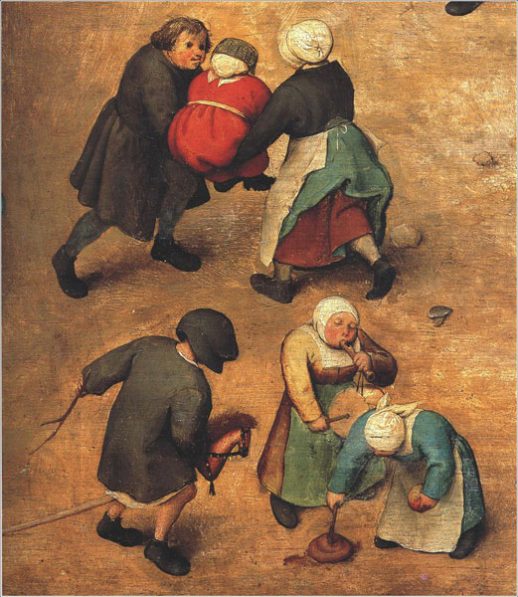

During the sixteenth century games were recognized both as a useful ally by tutors seeking to maximize the learning process and as tools for building physical strength and prowess. For this reason play was rarely allowed to be empty or mindless, and the playground was viewed as a legitimate extension of the classroom. The young girls in Meurier’s Guirlande are allowed to stroll in the garden for a quarter of an hour after their meal but are accompanied by the schoolmistress, who gives them a playful lesson in French.98 Ponocrates brings Gargantua dice and cards every day after lunch not to play but to learn “a thousand little tricks and novel inventions which come out of arithmetic,” while Vives argued that playground games provide an ideal opportunity for pupils to practice their Latin or Greek and recommended incorporating Latin into the scoring of a game by penalizing any boy who spoke in his native tongue.99 Bruegel’s painting is, of course, mute, but despite this it is hard to believe that the children are reciting Latin as they tussle. The emphasis on ethnographically accurate depictions of regional games is far more suggestive of the vernacular language found in Gargantua’s first, “untutored” game list. Yet despite this it should be noted that Children’s Games includes none of the gambling games and scatological games that fill Gargantua’s first game list. In fact, in the types of games that they undertake, Bruegel’s children generally appear to follow the advice of the humanist educators.

The broad variety of games presented by Bruegel is no doubt historically accurate. Nicholas Orme has highlighted how children’s social rank did not necessarily limit their culture, and while there is less evidence of the games played by poorer children, their repertoire of games was not necessarily narrower.100 Bruegel’s children engage in some of the same chivalric games listed in Gargantua, including swimming and tree climbing. But while Gargantua’s chivalric training is classically framed– he swims across the Seine holding a book high without wetting it “like Julius Caesar used to” and climbs trees “like another Milo”– the manner in which these feats are performed in Children’s Games is characterized by childlike ineptitude.101 The boy swimming in the river is clearly wearing inflated bladders as water wings, and the boy climbing a tree nearby does not swing from its branches “like another Milo” but clings on grimly, his feet barely off the ground. In other examples, Bruegel’s children invent prosaic versions of traditional “chivalric” activities using found objects– jousting with windmills, bowling with stones and counters, balancing brooms on their hands, and riding on barrels–and in this way continue to use play to test and stretch themselves physically. Children in the lower ranks of society benefited from greater freedom to roam and had access to the resources of the streets and workshops, factors which are also suggested in Bruegel’s image. In several cases, the children’s games mimic the more overtly educational activities undertaken by Gargantua under Ponocrates’s supervision. When it is raining Gargantua and Ponocrates tour the town and visit tradesmen; they see how metals are drawn and artillery cast; watch goldsmiths, alchemists, and coin minters at work; or visit the workshops of weavers, velvet makers, printers, and dyers.102 The notion of observing and mimicking a trade finds its equal in the right foreground of Children’s Games, where just above Bruegel’s signature a girl “plays” at scraping and measuring red brick dust in order to make pigment for paint, a trade which was unique to Antwerp.103 Gargantua heads to grassy meadows to botanize and perform experiments, such as separating water from diluted wine. Similarly investigative activities are also performed by several figures in Bruegel’s panorama. In the left foreground a solitary boy in a rush hat carefully examines the tail of a bird (see fig. 2), while at the far right of the panel a boy lies stretched across a log, engrossed in reaching out his net to catch a cloud of insects. In the middle foreground a lone girl inspects the bung hole of an upright barrel, apparently calling into it and testing its depth in relation to the sound of her voice (see fig. 3).

In addition to assessing the types of games that were included in Children’s Games it is also instructive to consider what Bruegel left out. Comparisons with Gargantua’s first game list highlight the notable absences of scatological games and gambling games from Bruegel’s panorama. Gargantua begins by playing over thirty card games before moving on to the table games of backgammon and knucklebones, meaning that gambling games occupy over a quarter of Rabelais’s total list. This significant area of play is barely represented in Children’s Games, although gambling games do feature in Bruegel’s other paintings from the period. Playing cards mingle with the debris of eggshells and bones littering the ground beside King Carnival’s barrel in the Battle Between Carnival and Lent, and in the left foreground of the panel a baker rolls dice to gamble his wares. In Netherlandish Proverbs, a fool in a parti-colored outfit perches on the tavern windowsill and scatters a deck of playing cards, and in the right foreground of Triumph of Death (1564), a backgammon board, playing cards, and coins are abandoned by a noble company as they attempt to escape an army of marauding skeletons. In each of these paintings cards and dice are explicitly linked to foolishness and the bodily actions of eating, drinking, defecating, and fornicating. While he scatters the playing cards, the fool in the window of Netherlandish Proverbs is also engaged in “shitting on the whole world”; the presentation of the upside-down globe as a kind of tavern sign making this impossibilia possible. A similar figure in a parti-colored hat pushes King Carnival’s barrel-sled past the scattered playing cards in Carnival and Lent, and the link between gambling and folly is again made by the jester in the Triumph of Death, who kneels on the floor among the scattered game pieces and tries to crawl under the table.

In contrast to these images, dice, cards, and gaming boards are conspicuously absent from Children’s Games. While the left foreground contains two “toys” that relate to games of chance, both depictions are somewhat ambiguous. Facing the bench with her back to the viewer a young girl clutches a white object which is often interpreted as a rattle (see fig. 2). Close inspection reveals the object to be a type of teetotum; a four-sided die embedded on a spindle, which was used to decide who would win the money in gambling games. The game to which the tool relates is listed by Rabelais as Pille, nade, jocque, fore a reference to the four different sides, or fates, which could befall the player once the top was spun.104 While it is possible that the girl in Bruegel’s painting is intending to spin the top on the bench before her, she looks far too young to possess either the coordination or funds for such a game. It is as though she has snatched up the adult toy and appropriated it for her own childish amusements: waving the trophy above her head, she attempts to catch the interest of the older boys playing on the other side of the bench and is seemingly oblivious to the spindle’s proper use. In front of this figure two older girls kneel and play a game with knucklebones. Their positioning is analogous to that of the baker gambling his wares in Carnival and Lent, and the motif has often been interpreted negatively as an example of foolish behavior.105 Kuncklebones are the tarsal joints of cloven-hoofed animals and had been used for gaming since ancient times; the ancient origins of the game were discussed in the sixteenth century by two male students in Erasmus’s colloquy “Knucklebones, or the game of Tali” (1529).106 After deciding on which rules to follow, Erasmus’s students lay stakes on the game, the outcome of which rests, like dice, on which way up the bones land. However, various games could be played with a set of knucklebones, not all of them games of chance; sometimes these games relied more on skill than on chance, for example when feats had to be performed while the bones are in the air.107 These versions of the game would doubtless have pleased Vives, whose Leges ludi states: “it must be a game in which mere chance does not count for everything. There must be some skill in it, which may balance chance.”108 Rabelais lists knucklebones twice, under two different names, Aux martres and Aux pingres, perhaps indicating these varieties. Images found in Ghent-Bruges manuscripts also suggest that there were many different types of games to be played with animal bones. Games with animal bones most frequently decorate the October pages of books of hours, in reference to the season in which the slaughter and butchering of livestock provided children with a host of new toys. In some of these examples bones are lined up ready to be bowled down like skittles (a version of this game is found in the street in the upper right of Children’s Games, where the bones are marshalled into a line along the receding wall of the civic building), while in other examples two players stand facing each other and cast their knucklebones with force on the ground. The variety and detail afforded to these illustrations in the manuscripts suggests that during the sixteenth century there was a wide variety of games that could be played with knucklebones and serves to caution against a single, moralistic interpretation of Bruegel’s motif.

In addition to excluding gambling games from Children’s Games, Bruegel also avoided many of the overtly vulgar and scatological games that feature in other sixteenth-century collections. In his first game list, Rabelais delights in listing a number of games involving excrement, as well as pet en guelle (fart-in-throat), a representation of which is found in the right foreground of Van Cleve’s Children’s Games.109 The object of pet en guelle was for one player to be inverted while the other grasped him around the waist. The pair would then form a living wheel, rolling over the backs of two more players. The game appears twice in the margins of a sixteenth-century French manuscript and was included in Jacques Stella’s collection of children’s games, Jeux et plaisirs d’enfance (1657), with an accompanying verse outlining the dangers of a game that called for one player’s face to be pressed into another’s behind.110 Bruegel clearly knew of this game as it is shown in the foreground of the print Kermis of Saint George (ca. 1559), being played by four adult peasants, but it is not included in Children’s Games. Instead the panel features just two scatological episodes; the girl urinating by the wall beyond the loggia and the girl stirring a pile of excrement in the left foreground.111

Some scholars have argued that these two scatological motifs underscore “the image of the child as untrained, lacking in control and not yet civilized,” but it could equally be argued that the children’s actions in these examples are primarily investigative rather than vulgar.112 The motif of a urinating boy was common in Ghent-Bruges manuscript borders and first appeared in the February miniature of the Grimani Breviary. Here a real-life puer mingens stands in the doorway of the peasant hut, raises his green tunic, and urinates in the snow; a detail surprising enough to be noted by one of the breviary’s first viewers, Marcantoni Michiel.113 In choosing a small girl rather than a boy as his protagonist and tucking her away at the back of the panel Bruegel rejected this tradition (see fig. 11). The little girl’s positioning, hidden from both her fellow players and from the casual viewer’s gaze, echoes Erasmus’s advice that relieving oneself should be done in private.114 ‘Crouching and lowering her head, she appears to be observing her own bodily function. The small girl stirring a pile of excrement with a stick in the foreground of Children’s Games is performing a more blatant experiment (fig. 14). Sometimes euphemistically described as a ‘mud-pie’, the presence of the potty nearby suggests that the object of the experiment is feces. Despite this, once again the girl’s concentrated manner means that the scatological aspect is almost completely lost; she stirs with all the laborious absorption of a baker making a cake.’

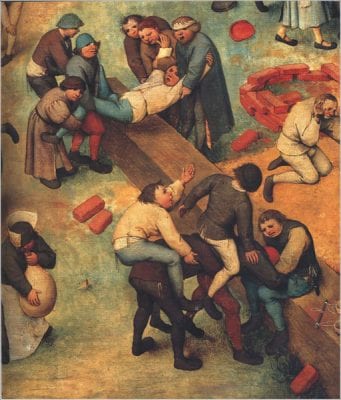

The negative view that Children’s Games presents a panorama of folly rather than of childhood was buttressed during the twentieth century by discussions about the physical appearance of Bruegel’s children, who have been described as both “miniature adults” and as “monsters.”115 The pedagogical texts can again provide some contemporary perspective on this aspect of Bruegel’s painting. When the population of Children’s Games is measured according to the strictures on comportment described in Erasmus’s De civilitate, the results are surprising. Behaviorally, the population of Children’s Games conforms to Erasmian guidance. Although they do not hold books or quill pens like Heemskerck’s twelve-year-old, neither do they yawn, spit, or poke their tongues out–all actions which Erasmus counseled against.116 Bruegel’s children play together harmoniously, reflecting Vives’s advice that “companions should be agreeable, festive, with whom there is no danger of quarrelling or fighting, or either doing or saying anything disgraceful or unbecoming.” This advice is rejected by the children in the prints. Havoc is created in The Cobbler and His Wife as a Teacher by the children who escape unnoticed through the doorway, help themselves to food and drink, and play games with dice. The print also contains examples of fighting; in the right foreground a group of children pull hair and hit each other with baskets, while on the left a child wearing an adult mask frightens several of his playmates, who try to scramble away.117 To the right of Children’s Games there are two motifs that could similarly be interpreted as examples of malicious play–one group of boys is engaged in “pulling hair,” while another group holds their playmate’s arms and legs and swing him over the beam (fig. 15). In both cases, the facial expressions of the central players indicate that they are not relishing their role as victims, but as Edward Snow has highlighted, these games epitomize the fine line between exhilaration and distress which is often at work in play, as the boys gather together to “give” an experience to one member of the group.118 Snow plausibly suggests that the first game may not be hair pulling at all but instead some kind of game of “oratory” in which the central figure holds power over the gaping figures who surround him and jostle to touch his head. Most of the games in the panel supply less ambiguous demonstrations of children cooperating and playing harmoniously together for the mutual benefit of one another. The game of leap-frog, which quietly plods across the center of the panel, provides an example of how, by pursuing their games so intently, Bruegel’s children demonstrate many positive attributes. The games of tug-of-war and bucca (“how many horns does the goat have”) demonstrate team spirit and patience as players bend to support others on their backs. Physical agility and bravery are embodied by the boy walking on high stilts, who is being cheered on by a small girl with outstretched arms below him. In other examples, the children appear to learn from each other–the trio riding the red fence displaying various stages in the gradual mastery of an activity.

In the majority of instances Bruegel’s children are attired appropriately, and physically they broadly conform to Erasmian ideals. The children’s clothes are clean and neither conspicuously shabby nor obviously indicative of opulence, both extremes which Erasmus warned against.119 As was the custom at the time, the younger children of both sexes wear dresses, and their aprons and bibs are neatly tied and blemish free. All of the girls wear their hair tucked away in bonnets, and hats are commonly worn by the boys. Although often slightly unkempt, the boys’ hair is hardly that of savages; with the exception of the boy rolling the hoop in the foreground and one of the boys swinging another over the beam on the right, most seem to follow Erasmus’s advice that hair should “neither flow down the shoulders nor cover the brow.”120 Erasmus counseled against exposing, save for natural reasons, “the parts of the body which nature has invested with modesty,” and again this advice is followed by Bruegel’s children. In contrast to the figure in the foreground of The Ass in School, who sits with his tunic gaping open and his genitalia on display, the tunics of the older boys in Children’s Games are all fastened tightly with belts or string. In the area beside the red fence the children undertake various acrobatics, their actions providing the potential for physical exposure. This appears to have been actively avoided, however, in the example of the boy caught midway through the act of upending himself. His tunic has fallen forward, revealing his breeches, but his modesty is preserved by a white undershirt that hangs down and covers his behind.

According to the De civilitate, a child’s face is the strongest manifestation of his mind and so should be calm. While Heemskerck’s sitter perfectly embodies this advice, making inferences from facial expressions is more problematic with a painter like Bruegel, who frequently chose to turn his figures away from the viewer or disguise faces with hats. Even when they are captured the children’s facial expressions are not dealt with in detail, but instead are types. Boisterous older boys are shown as wide-eyed and open-mouthed, such as the boys playing on the beam (see fig. 15), or with their facial expressions fixed in concentration, such as those in the tug-of-war (see fig. 3). Younger children often appear moon-faced and struck dumb by events (see fig. 13). Sixteenth-century viewers might have felt that the unrestrained facial expressions of Bruegel’s children were not ideal, but they are at least believably childlike, unlike the mature faces and tonsured or balding heads of the pupils in the Ass in School. Even more descriptive are the bodies of Bruegel’s children, which are everywhere engaged in the gauche physicality of play. From the small boy hopping clumsily forward on his hobbyhorse (see fig. 14) to the older boy scrabbling to stay astride the barrel (see fig. 3), the manner in which the children struggle to gain command of their bodies resonates as much with modern viewers as it would have done with Bruegel’s original audience.

Children’s Games, like its sister works Carnival and Lent and Netherlandish Proverbs, rejects a single iconographic program in favor of something more multivalent. Within each of these paintings, the emotive charge of the familiar subject matter is heightened by Bruegel’s encyclopedic compositional strategies, which serve to invite individual, highly subjective responses. All three works were large and expensive to produce, factors which would doubtless have contributed to the thrill of navigating their complex iconography for Bruegel’s mercantile buyers. A recognition that Children’s Games was in itself a type of toy, capable of satisfying diverse arguments, should not preclude attempts to situate the panel within its proper historical context. By the middle of the sixteenth century concerns over the conduct and education of children converged with an interest in their play, and this would have influenced the reception of Bruegel’s painting. Suggestions as to how contemporaries might have “played” with Children’s Games can be arrived at by exploring the ways in which the educational texts mesh with details found in the panel and with the interests of Bruegel’s known patrons and associates in Antwerp. The texts provide an insight into the types of people to whom the painting might have appealed: from someone directly involved in the upbringing or instruction of children to the parents of pupils registered at Heyns’s De Lauwerboom school. More fundamentally, they demonstrate the importance of games in sixteenth-century life and provide a means of measuring Children’s Games according to contemporary standards, serving to shift our perspective on the panel away from the moralizing judgments of seventeenth-century emblem literature and toward the celebratory attitude to play that flourished among the sixteenth-century humanists.