This paper examines the export of Dutch paintings to Denmark and Sweden during the seventeenth century. Published household inventories from several Danish and Swedish towns reveal patterns of ownership, suggesting a demand for Dutch paintings associated with the presence of Dutch immigrant communities, while toll records document shipments of paintings through the Sound. By addressing gaps in the evidence, the paper highlights challenges in tracing the trade in paintings to the region and proposes directions for future research, including exploring alternative trade routes.

Danish and Swedish probate inventories reveal the tantalizing possibility that Dutch paintings were exported to the Baltic region in significant numbers during the seventeenth century. Although these inventories do not name painters, hundreds of paintings are described as hollandsk (Dutch). In Denmark, the prevalence of Dutch paintings is particularly evident in the port city of Helsingør, strategically located on the Øresund Strait (known as “The Sound” in English), where all trade ships bound for the Baltic Sea passed through customs inspections and paid tolls. Inventories drawn up there in the seventeenth century include descriptions such as “Nok tre hollandske Malinger med Rammer” (another three Dutch paintings with frames) (1618) and “8 hollandske malede stykker” (8 Dutch painted pieces) (1656).1 Similarly, inventories drawn up in the Swedish capital of Stockholm demonstrate a comparable quantity of Dutch paintings in Swedish households.2 Helsingør and Stockholm are not isolated cases: inventories in the smaller Danish towns of Aalborg, Køge, and Ribe, as well as the Swedish trade town Gothenburg, also sporadically describe paintings as being Dutch.

Drawing from a collection of published inventories and additional archival sources, including toll records and custom rolls, this paper explores the volume and nature of Dutch painting exports to the Baltic region during the seventeenth century. These sources document the presence of Dutch paintings but do not provide direct evidence of the specific works involved. As such, this study relies on historical documents rather than identifiable paintings; its illustrations include both works known to have been acquired by the courts and examples of the types of paintings that may have been exported to the region in the seventeenth century.

The inventories under study have in common that they were drawn up in cities and towns with large Dutch immigrant communities. These communities likely played a key role in the introduction and dissemination of Dutch paintings. Paintings may have been traded alongside other commodities as part of a broader strategy to export Dutch cultural goods. Research on the ownership of Dutch pottery, faience, earthenware, and tiles in the region suggests that these objects were initially found primarily in immigrant households, with ownership expanding to local populations in subsequent decades. This may have been the case with Dutch paintings as well, though further research is needed to confirm this.

In this paper, Denmark and Sweden serve as case studies due to the greater availability of published sources from those areas. However, the findings may also be applicable to other parts of the Baltic region, where Dutch immigrant communities and Dutch cultural influences were similarly significant.

Dutch Exports of Paintings

In recent decades, art historians have increasingly explored the international dimension of the early modern art market, with a particular focus on Flemish exports, which are well documented.3 Much of what we know about this export trade comes from the surviving administrative records of Antwerp dealers. These show that the Flemish export trade was highly organized, with Antwerp serving as the central hub for the production and distribution of paintings. Flemish dealers such as Matthijs Musson (1598–1678) and Guilliam Forchondt (1645–1677) played a pivotal role in this trade, coordinating the production, sale, and shipment of thousands of paintings to the Dutch Republic, France, Spain, Portugal, and even Latin America.4 Business networks of merchants at these destinations kept the dealers informed about local tastes and demands, while the dealers commissioned workshops in Antwerp and Mechelen to mass-produce paintings tailored to these foreign preferences.

In contrast, the study of seventeenth-century exports of paintings from the Dutch Republic faces challenges due to the relative scarcity of primary sources and detailed records compared to Flemish ones. Notable examples of high-end deliveries illustrate some organized export efforts by Dutch dealers, although they went to foreign courts instead of the free market. These examples include Hendrick Uylenburgh’s (1587–1661) deliveries of paintings to King Sigismund III Vasa of Poland (r. 1587–1632) in 1620 and 1621, Johannes de Renialme’s (1593/4–1657) offer of a large quantity of paintings by the Dutch Republic’s most expensive and celebrated painters to Friedrich Wilhelm, the Great Elector of Brandenburg (r. 1640–1688) in 1651, and Gerrit Uylenburgh’s (1625–1679) shipment of paintings and classical sculptures to the same in 1671.5

The extensive export of Dutch paintings is often believed to have begun only in the eighteenth century, when many paintings reentered the art market after their owners’ deaths, leading to a lively international trade.6 However, much like in Flanders, the flourishing art market in the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century had already created the necessary conditions for an organized export of newly produced artworks. The market was highly commercialized, with paintings produced, marketed, sold, and bought on a large scale. Hundreds of painters were active in production centers such as Amsterdam, Delft, Leiden, and The Hague. Art dealers managed shops with large quantities of paintings in stock, offering a variety of styles, subjects, and prices. They used novel distribution channels such as auctions, lotteries, and games to market and sell their supply. Furthermore, the Dutch Republic had international trade networks and a well-developed maritime infrastructure, both key elements for facilitating the export of goods, including paintings.

Denmark and Sweden would have been logical destinations for Dutch art dealers seeking international markets for their paintings, for three important reasons. First, large, relatively new communities of Dutch immigrants existed in the Baltic region, including in the Danish cities of Helsingør, Aalborg, Køge, and Ribe, as well as in the Swedish cities of Stockholm and Gothenburg. As was the case with Flemish immigrants abroad, these communities likely desired paintings to decorate their homes, as had been their custom in the Dutch Republic. In this, the Dutch export practice might have had parallels with—or was perhaps even modeled after—the Flemish exports.

Second, strong artistic links existed between the Dutch Republic and Denmark and Sweden, especially at the royal courts.7 The Danish kings appointed Dutch artists as court painters, including Pieter Isaacsz (1568–1625), Karel van Mander III (1609–1670), and Toussaint Gelton (1630–1680); in Sweden, figures like David Beck (1621–1656), Martin Mijtens (1648–1736), and Hendrick Munnickhoven (d. 1664) filled this role.8 These court artists not only painted portraits of the monarchs and their families but also managed decoration projects and purchased pieces for the royal collection. The works were frequently sourced from the Dutch Republic. One notable example is the decoration of Christian IV’s (r. 1596–1648) private oratory at Frederiksborg Castle in 1618–1620, for which Pieter Isaacsz commissioned twenty-two paintings depicting scenes from the life of Christ. He entrusted the work to artists he knew from Amsterdam, including his former pupil Adriaen van Nieulandt (1586/87–1658) and his neighbor Pieter Lastman (1583–1633). None of these works survived the fire of 1859, but Heinrich Hansen’s (Danish, 1821–1890) paintings of the oratory’s interior, created shortly before, offer a valuable glimpse into the original decoration program (fig. 1).9

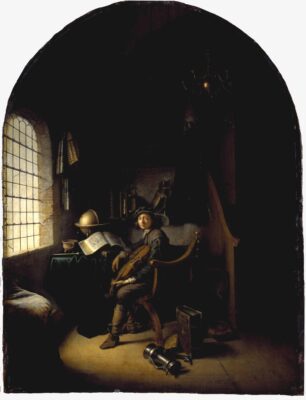

The Danish and Swedish rulers turned to the Dutch Republic in other ways too, with Danish King Christian IV sending envoys to the Dutch Republic to acquire art for his collection and recruit Dutch merchants and artisans. In this context, Jonas Charisius (1571–1619) bought 148 paintings in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Delft, and Antwerp in 1607 and 1608, by artists such as Frans Badens (1572–1618), Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem (1562–1638), Gillis van Coninxloo (1544–1607), and Otto van Veen (1556–1629).10 Similarly, Theodorus Rodenburg (ca. 1574–1644) was sent to the Low Countries in 1621 and returned to Denmark with 350 paintings, mostly by Dutch masters.11 In Sweden, agents such as Michel le Blon (1587–1656), Harald Appelboom (1612–1674), and Peter Spiering van Silvercroon (1594/6–1652) mediated art purchases for the royal family.12 Spiering is well-known among art historians for sending eleven paintings by Gerard Dou (1613–1675) to Queen Christina (r. 1632–1654) in 1652, including An Interior with a Young Viola Player (fig. 2). She returned these, most authors assume, because she preferred Italian art.13

The Swedish nobility also had a keen interest in Dutch art and culture, reflecting a broader fascination with the Dutch Republic as a model in many aspects of society, particularly in trade. Close economic ties with the Republic played a significant role in Sweden’s increasing prosperity during the seventeenth century. Dutch architectural styles and city planning left their mark on Swedish towns, while large numbers of aristocratic youths were sent to the Republic to acquire expertise in science, trade, and military practices. The aristocracy’s demand for luxury products was largely directed toward the Dutch market, and the same agents who facilitated art purchases for the royal family also supplied the aristocracy with high-quality paintings, along with the latest political and commercial news from Amsterdam.14

The interest of the Danish nobility in Dutch art during the seventeenth century is less well studied. While Dutch influences in architecture remain evident today, they were likely the result of royal initiatives to recruit Dutch builders rather than the independent efforts of members of the nobility. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most Danish noble families appear to have prioritized commissioning portraits—often from Netherlandish painters associated with the royal court—over forming art collections.15 It was only in the eighteenth century that the Danish nobility began to collect art on a large scale, purchasing pre-owned paintings en masse through dealers and at auctions in Amsterdam and Hamburg.16

A third reason why Dutch art dealers could have targeted Denmark and Sweden was the available trade infrastructure. The Dutch dominated imports and exports on the Baltic Sea. Hundreds of ships departed from Dutch harbors each year to collect Baltic grain, so essential to the Dutch economy that this trade earned the meaningful title of moedernegotie (mother of all trade). The Dutch also imported raw materials such as wood, copper, and iron, while exporting salt, wine, manufactured goods, and luxury products.17 To avoid sailing to the Baltic with empty holds, the Dutch were always seeking commodities to take eastward. Given the developed art market in the Dutch Republic, it is more than plausible that paintings were included among the goods exported.

Households with Dutch Paintings in Denmark and Sweden

The most substantial research on painting ownership in households in the region has been done for Helsingør (fig. 3). Many immigrants lived or settled there in the second half of the sixteenth century, and there was a large Dutch community.18 Historian Jørgen Olrik investigated the inventories dated 1572 to 1620 and published the paintings and prints therein, while Poul Eller later analyzed and transcribed 1,771 household inventories from 1621 to 1660 and published his findings as well.19 In addition, the recent project Urban Diaspora—Diaspora Communities and Materiality in Early Modern Urban Centers (2014–2019), supervised by Jette Linaa, has resulted in a database of 1,300 Helsingør household inventories (1571–1650).20 Unfortunately, this database is not publicly accessible, but the analysis of these inventories in the related book, Urban Diaspora: The Rise and Fall of Diaspora Communities in Early Modern Denmark and Sweden, Archaeology – History – Science, includes a two-page paragraph on the paintings in Helsingør homes.21

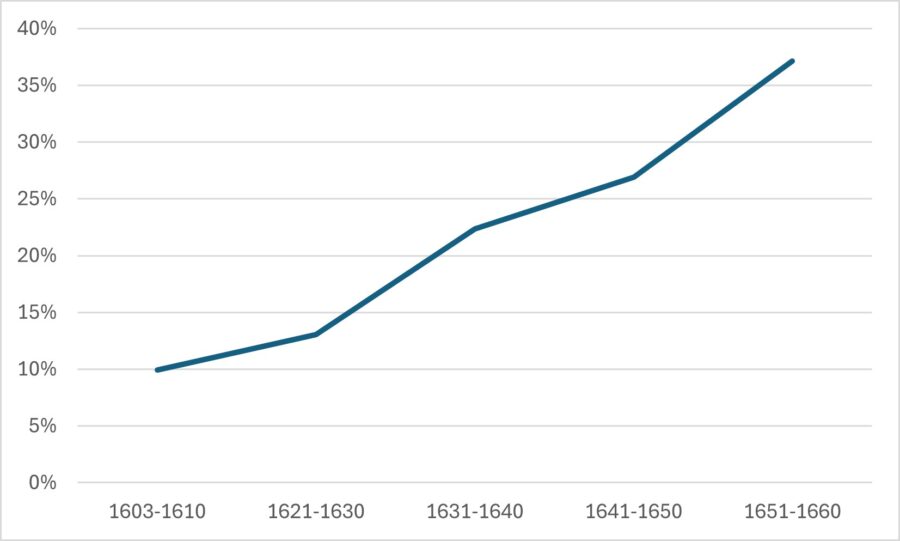

Percentage of all drawn-up inventories in Helsingør with paintings, per decade (1603–1660)

(source: Eller, Borgerne og Billedkunsten, p. 29) [side-by-side viewer]

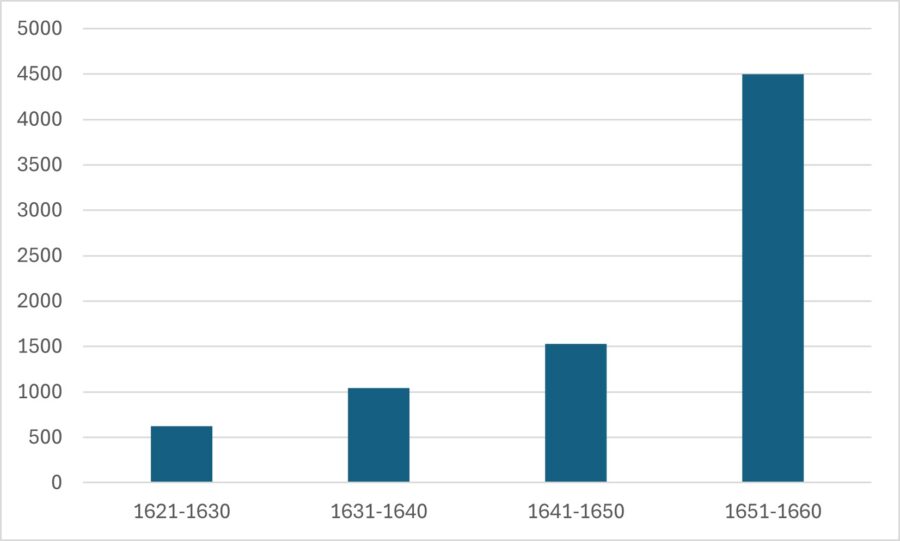

As early as 1585, Helsingør inventories included paintings.22 Similar to the trends observed in Dutch cities, paintings were only occasionally recorded in inventories in the last decades of the sixteenth century, becoming more widespread in the first half of the seventeenth century. In Helsingør, the percentage of inventories that listed paintings and prints more than tripled, from about 10 percent in the first decade of the seventeenth century to 37 percent in the 1650s (fig. 4). The total number of paintings inventoried also rose steeply over the century, from five hundred paintings in the 1620s to 4,500 paintings in the 1650s (fig. 5). Overall, 492 households included a total of 7,692 paintings. The entry in Charles Ogier’s diary during his stay in Helsingør on August 12, 1634, is telling, recalling contemporaneous accounts of travelers in Holland: “Plurimas privatorum domos perlustravi, easque nitidissimas, et circumquaque picturis decoratas, nec non scriniis et armariis politissimis ornatas” (I inspected many private houses and they were very beautiful, and everywhere adorned with paintings and adorned with the most beautiful chests and cabinets).23

Total number of paintings in inventories in Helsingør, per decade 1621–1660

The paintings listed in Helsingør inventories do not include the names of the artists, making it nearly impossible to identify the works in collections today (if they have survived at all). In contrast, more than one-third of them were recorded with their subject, demonstrating that the citizens of Helsingør had an evident preference for history painting—biblical narratives in particular.24 Citizens owned works that we would also expect in households in the Dutch Republic: scenes from the Old Testament—many from the book of Genesis—and the life of Christ, the Five Senses, pictures of Venus, genre paintings with peasants, still-lifes, landscapes, and marines. Furthermore, we find, as one would expect, portraits of Danish kings and princes.

Table 1 - Dutch paintings listed in inventories in Helsingør (1618-1659), in chronological order

| Date (m/d/y) | Total no. paintings | Dutch paintings | Notes on the owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4/29/1618 | 10 | Nok 3 hollandske Malinger med Rammer [Another three Dutch paintings with frames] | Captain Johan Sems |

| 8/2/1631 | 62 | 1 hollandsk tavle, 5 dlr [1 Dutch painting, 5 dlr] | Sille Harder, “skrivers” (printer/writer) |

| 3/1/1641 | 24 | 6 hollandske stykker, met forgyldte rammer a 3 mk = 4,5 dlr [6 Dutch pieces, with gilded frames a 3 mk = 4,5 dlr] | Margarethe Eshen, wife of captain Marcus Witte |

| 2/29/1644 | 32 | 3 hollandske tavler a 1 mk = 3 mk [3 Dutch paintings a 1 mk = 3 mk] | Karen Gregdsdatter, wife of Hans Piper |

| 4/5/1644 | 22 | 2 hollandske stykker a 3 mk = 1,5 dlr [2 Dutch pieces a 3 mk = 3mk] | Frantz Eriksen, husband of Anne Jacobsdotter. His half-brother Niels Eriksen served King Christian IV. |

| 5/6/1647 | 23 | 1 hollandsk stykke; 4 hollandske stykker skilderi [1 Dutch piece, 4 Dutch pieces of paintings] | Katrine Wibrandt, wife of Johan Weyes |

| 3/28/1650 | 10 | 1 lidet hollandsk stykke 3 mk [1 small Dutch piece 3 mk] | Lodvid Slagter |

| 9/7/1652 | 93 | 5 historie, hollandske, oliefarve a 5 mk = 6 dlr 1 mk [5 history, Dutch, oil paint a 5 mk = 6 dlr] | Peder Christensen, chaplain |

| 2/1/1653 | 16 | 6 hollandske stykker a 12 sk = 4,5 mk [6 Dutch pieces a 12 sk = 4,5 mk] | Joachim Niemand, pewterer |

| 4/13/1653 | 37 | 7 hollandske stykker på væggen, lige store og lige gode, hvert stykke 1 dlr 1 ort = 13 dlr 8 sk [7 Dutch pieces on the wall, all the same size and all equally good, each piece 1 dlr 1 ort = 13 dlr 8 sk] | Peter Borchmand wine merchant and Dutch consul resident, husband of Anne Pedersdatter |

| 8/15/1654 | 26 | 8 hollandsk stykker a 2 mk = 4 dlr [8 Dutch pieces a 2 mk = 4 dlr] | Captain Alexander Arrat and wife Johanne Ross |

| 9/2/1654 | 18 | 7 hollandske stykker små [7 Dutch pieces small] | Tilche Simmens |

| 10/22/1654 | 32 | 8 hollandske stykker a 1 dlr = 8 dlr [8 Dutch pieces a 1 dlr = 8 dlr] | Anniche Hans Petersens |

| 1/24/1655 | 38 | 4 hollandske stykker i ramme 3 mk [4 Dutch pieces with frames 3 mk] | Kirstine Hendriksdatter, wife of M. Anders Baldtzer, barber |

| 8/7/1655 | 4 | 4 hollandske stykker a 1 mk = 1 dlr [4 Dutch pieces a 1 mk = 1 dlr] | Jacob Clemidsen, sailor, husband of Dorette Lauridsdatter |

| 1/10/1656 | 25 | 8 hollandske malede stykker a 12 sk = 6 mk [8 Dutch painted pieces a 12 sk = 6 mk] | Peter Folkvin, husband of Kirsten Bendtsdatter |

| 5/7/1656 | 9 | 9 gamle hollandske kontrafej, vurderet for 6 mk [9 old Dutch portraits (or pictures), valued at 6 mk] | Tore Laurids Arentsens |

| 5/29/1657 | 7 | 4 hollandske stykker af træ 12 sk [4 Dutch pieces on wood 12 sk] | Peder Andersen, husband of Karen |

| 11/6/1657 | 23 | 3 hollandske tavler på træ 3 mk [3 Dutch paintings on wood 3 mk] | Joachim Skarlacken, bailliff’s assistant, husband of Maren |

| 7/6/1658 | 5 | 1 hollandsk stykke 3 mk, 1 hollandsk stykke 1 mk [1 Dutch piece 3mk; 1 Dutch piece 1 mk] | Kirstine, wife of Johan Brandt, mother of Johan Brandt, journeyman or surgeon |

| 7/16/1658 | 98 | 9 nye hollandske stykker a 3 mk = 6 dlr 3 mk [9 new Dutch pieces a 3 mk = 6 dlr 3 mk] | Hans Kruse, merchant and shop owner. His son Johan Hansen Kruse is registered as being in Holland. |

| 4/28/1659 | 4 | 4 hollandske stykker a 8 sk = 2 mk [4 Dutch pieces a 8 sk = 2mk] | Dorithe Lauridsdatter, wife of Broder Hansen, sailor |

| 10/19/1659 | 17 | 3 hollandske malede stykker, nok 2 ditto, a 1 dlr = 5 dlr [3 Dutch painted pieces, another 2 ditto, a 1 dlr = 5 dlr] | Jan Jansen, baker |

| Source: 1618: Olrik, Borgerlige Hjem i Helsingør for 300 Aar siden (1903), 13–14. Other years: Eller, Borgerne og billedkunsten (1975), 145–172. 1 rigsdaler (rd) = 6 marks (mk) 1 seltdeler (dlr) = 4 marks (mk) 1 mark (mk) = 16 skillings (sk) Tavler can be translated as “board,” “panel,” or “painting,” and stykker as “pieces.” For clarity in this table, all such terms have been translated as “paintings” and “pieces,” though in some cases they may also refer to prints and print boards. |

|||

In addition, 112 paintings in twenty-five unique inventories are described as hollandsk (Table 1). Their subject matter is not specified, indicating that their “Dutchness” was the strongest identifier. In the entire Helsingør dataset, no other such geographical description is used, raising questions about its meaning and what made the scribes of these particular inventories recognize the paintings as “Dutch.” It is plausible that many of the paintings listed by their subject, instead of as hollandsk, might have been made in the Dutch Republic too. Of some of these, their origins are clear from their subject matter, including views of Amsterdam, The Hague, or the Dutch towns of Zierikzee and Gertrudenberg; allegorical scenes of “Hollands Triumf” (The Triumph of Holland) and “hollandske Fred” (Dutch Peace); and portraits of the Prince of Orange. These were likely produced in the Dutch Republic and were probably most in vogue among Dutch immigrants, who were numerous in Helsingør. Additionally, the many biblical scenes, produced in large numbers for the free market in the Dutch Republic, may well have been among the imported works.25

The inventories document the presence of Dutch paintings, but not in enough detail to identify the specific works involved. To give an idea of the type of painting that may have been among the “hollandske skilderien” (Dutch paintings) listed in these inventories, The Meeting of Abigail and David from the circle of Jacob de Wet (ca. 1610–after 1677) and River Landscape with a Tower by Willem Kool (1608–1666; fig. 6 and fig. 7) are recorded in Denmark from the mid-eighteenth century onward, though they may have been present as early as the seventeenth century.26

The situation in the Danish capital of Copenhagen, by far the nation’s largest city, was doubtlessly like that in Helsingør.27 Most of the inventories drawn up in Copenhagen before 1680 have not survived. In 1930, Hans Werner studied the preserved deeds and concluded that, around 1700, almost all moderately well-to-do middle-class homes in Copenhagen had their walls adorned with paintings and prints.28 As an example, his article includes a transcription of the 1691 inventory of the Danish-born civil servant Rasmus Schøller (1639–1690), which lists twenty paintings, nine of them described as hollandsk.29 The fact that painting dealers were active in Copenhagen also demonstrates that there was demand in the city. Among them was the merchant Johan Bøfke (1612–1681), whose shop inventory from 1681 lists fifty-four paintings.30 Another painting seller was Caspar de Cocquiel (active 1691–1699) from Antwerp, who in 1696 was granted citizenship in Copenhagen, along with the right “to earn his living exclusively by selling paintings,” by privilege of the king.31

Seventeenth-century inventories from several other Danish cities have been subject to socioeconomic studies, which address the ownership of paintings in passing. For instance, Aalborg, a prosperous port city in northern Jutland, second in size only to Copenhagen in the seventeenth century, has probate inventories preserved from 1606 onward. These are an important source in Jakob Ørnbjerg’s dissertation on the socioeconomic development of the gentry in Aalborg, where he concludes that the local regent class owned pictures, mostly portraits and “histories,” of which some were Dutch.32 Similarly, Ribe, a town in southwest Jutland, has inventories preserved from 1646 that Ole Degn, in Rig of Fattig i Ribe, studied to explore the town’s economic and social conditions.33 Degn’s study lists the types of objects owned by mayors, aldermen, and some merchants, which include Dutch paintings and prints, though he does not discuss painting ownership in detail.34 That Dutch paintings could be bought in Ribe is also clear from a source presented by Ebby Nyborg in an article about local painters, demonstrating that the painting dealer Hans Nielsen Friis (1587–1650) sold Dutch paintings in his shop in the first half of the seventeenth century.35 Lastly, Køge, a small seaport town 39 kilometers southwest of Copenhagen, has household inventories preserved from 1593 on. Victor Hermansen’s article from 1951 discusses several of these inventories that contain paintings.36 The town’s mayor, Enevold Rasmussen Brochmand (1593–1653), owned more than one hundred paintings, mainly biblical scenes and portraits of family members. Most of these were of modest value. In 1992, Gerd Neubert published a selection of twenty-four household inventories, of which twelve contained paintings, including “2 small Dutch pieces.”37

Stockholm was the most important Swedish trade city on the Baltic Sea and home to a large Dutch community. Inventories drawn up there have been preserved from 1661 on, and those that contain artworks are the subject of a chapter in Olof Granberg’s Svenska konstsamlingarnas historia från Gustav Vasas tid till våra dagar (The history of Swedish art collections from the time of Gustav Vasa to the present day). Granberg provides an overview of the more important collections until 1747, including transcriptions of the paintings in these inventories. These suggest that many burghers owned art in the city.38 Some names of locally operating painters are listed in these inventories, including David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl (1628–1698), who was German by birth and studied painting in Amsterdam (fig. 8).39

The inventories transcribed by Granberg include 325 mentions of “Hollänska schillerier” (Dutch paintings) in forty-two unique inventories (Table 2).40 In contrast to Helsingør, other geographic origins are also listed in the set of inventories: fourteen French paintings, ten “Brabantska schillerier” (Flemish paintings), and two Italian paintings. In Stockholm, many of the paintings labeled as Dutch were further described with their subjects. These show that the hollänska schillerier had a wide variety of subjects, ranging from landscapes, still-lifes, and marines to biblical scenes. Examples include “1 Hollandz Schillerey af Fruchter” (one Dutch painting with fruits) (1670), “1 Holländsk Tafla med Skepp” (one Dutch panel with ship), “1 Stoort Hollandz Schillerie, Landskap” (one large Dutch painting, landscape) (1709), and “1 Holländskt stycke, som föreställer de tre män i den brinande ugnen” (one Dutch piece, depicting the three men in the burning furnace) (1745).

Table 2 - Dutch paintings listed in inventories in Stockholm (1670-1747), in chronological order

| Date | Total no. paintings | Dutch paintings and paintings with other geographic specification | Notes on the owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1670 | 68 | 1 Hollandz Schillerey af Fruchter, 4 dlr [1 Dutch painting with fruits] | Jacob Rebeledi, merchant |

| 1673 | 66 | 1 Hollensk Dame 3 dlr; 2 små Hollendska bondstycken, 5 dlr; 1 lijtet Hollands stycke, 5 dlr; 13 st. Hollendska landskap, 26 dlr; 6 st. små dito, 6 dlr; [1 Dutch Lady, 3 dlr; 2 small Dutch peasant pieces, 5 dlr; 1 small Dutch piece, 5 dlr; 13 pieces Dutch landscape, 26 dlr; 6 pieces small ditto, 6 dlr] | Hindrick Meurman, alderman and founder of the silk trade |

| 1675 | 4 st. Hållenska måladhe tavlor [4 pieces Dutch painted panels] | Anthony Grill the Elder, from Holland, maintained a distinctly Dutch household with Dutch pewter, stoneware, beds, etc. | |

| 1677 | 30 | Holländska mångelskor, 5 dlr [Dutch stallholder (?), 5 dlr ] | Lars Linderoot, merchant |

| 1677 | - | 8 Holländska Taflor, 24 dlr [8 Dutch paintings, 24 dlr] | Wife of the chorister Hindrich Perrman |

| 1678 | 38 | 1 Hållandsz Schillerie, Resestycke, 30 dlr; 18 små Hollenska taflor, 36 dlr [1 Dutch paintings, travel piece, 30 dlr; 18 small Dutch paintings, 36 dlr] | Wife of the notary Carl Feiff |

| 1678 | - | 2 st. Hållenska Taflor [2 pieces Dutch paintings] | Anders Olderman, wealthy merchant from Germany |

| 1678 | 50 | 2 st. Conterfej medh Hållendara och Hållenska, 16 dlr; 2 Hållenska dito med Skepp, 10 dlr [2 pieces of portraits with Dutchman and Dutchwoman, 16 dlr; 2 Dutch ditto with ship, 10 dlr] | Melchior Jung glassworks manager |

| 1678 | - | 7 st. Hålländska Taflor, 56 dlr; 7 st Hållänska dito, 56 dlr [7 piece Dutch paintings, 56 dlr; 7 piece Dutch ditto, 56 dlr] | Wife of Gert Hanssons, wine merchant |

| 1679 | 40 | 7 st. Hållänske dito [Taflor], 84 dlr [7 piece Dutch paintings, 84 dlr] | Elias Thede, carpenter |

| 1682 | 80 | 3 st. Hållenska Siötaflor, 30 dlr; 4 st. Hollänska, 6 dlr [3 pieces Dutch sea panels, 30 dlr; 4 pieces Dutch, 6 dlr] | Werner Smeer, royal cellar master |

| 1683 | 30 | 4 Hållenska Skillerier kiöpte Ao 1663, 64 dlr; 8 Dito mindre, 36 dlr; 7 st. Hållenska Skillerier kiöpte A0 1669, 140 dlr [4 Dutch paintings purchased in 1663, 64 dlr; 8 dito smaller, 36 dlr; 7 pieces Dutch paintings purchased in 1669] | Wife of Petter Ernest |

| 1688 | 63 | 1 Holländsk Tafla med Skepp på 6 dlr; 12 Holländska Taflor, 58 dlr; 2 st. Holländska 8-kantiga Taflor, 8 dlr [1 Dutch painting with ship of 6 dlr; 12 Dutch paintings, 58 dlr; 2 pieces Dutch octagon paintings, 8 dlr] | Wife of merchant Lorentz Altenechs |

| 1690 | 14 | 6 st. Hållendske Schillerier, 56 dlr [6 pieces Dutch paintings, 56 dlr] | Petter Wolker, secretary |

| 1691 | 50 | 2 fijna Hållenske, 30 dlr; 5 st. små Hollenske Schillerier 15 dlr [2 fine Dutch (paintings), 30 dlr; 5 small Dutch paintings, 15 dlr] | Wife of Arvid Noréen, alderman |

| 1693/1730 | 44 | 1 hollänskt stycke, 36 dlr [1 Dutch piece, 36 dlr] | Amalia Horleman, wife of merchant Sophonias Kroger |

| 1694 | - | 7 st. Hollenska taflor på trä, 35 dlr; 1 litet Hollandz Stycke, 12 dlr [7 pieces Dutch paintings on wood, 35; 1 small Dutch piece, 12 dlr] | Petter Carling, alderman |

| 1696 | - | 3 stora Hållänska Schillerier, 48 dlr; 4 st. stoora Hållenska Schillerier, 80 dlr; 3 st. Dito smärre, 18 dlr; 7 st. Hållenska Schillerier, 35 dlr; 1 Hållänskt Schillerie för 4 dlr; 1 Hållänskt Schillerie, 2 dlr; 1 dito, 6 dlr [3 large Dutch paintings, 48 dlr; 4 pieces large Dutch paintings, 80 dlr; 3 pieces ditto smaller, 18 dlr; 7 pieces Dutch paintings, 35 dlr; 1 Dutch paintings for 4 dlr; 1 Dutch painting, 2 dlr; 1 dito, 6 dlr] | Joran Wiens, commissioner |

| 1699 | - | 16 st. Hållenska Schillerier [16 pieces Dutch paintings] | Wine merchant Mathias Ditmar |

| 1699 | - | 14 st. Hållenska Schillerier [14 pieces Dutch paintings] | Merchant Daniel Bergman |

| 1699 | - | 1 stoort Hållans Schillerie af ett landskap, 40 dlr; 4 st. fijna Hållans Schillerier, 62 dlr [1 large Dutch painting of a landscape, 40 dlr; 4 pieces fine Dutch paintings, 62 dlr] | Merchant Matthias Pettersson |

| 1699 | - | 3 st. Hållenska Schillerier, 12 dlr [3 pieces Dutch paintings, 12 dlr] | Juliana von Kothen, widow of the court peltiner and alderman Elias Vult |

| 1701 | 19 | 3 st. Hållänska taflor, 18 dlr; 1 Hollänsk Skogztafla, 10 dlr [3 pieces Dutch paintings, 18 dlr; 1 Dutch painting of a forest, 10 dlr] | Frans Boll, gold smith |

| 1706 | 43 | 17 Hållenska stycken, 45 dlr [17 Dutch pieces, 45 dlr] | Daniel Törner, alderman |

| 1707 | - | 1 Hållenskt Schillerie med Simsons Historia, 9 dlr; 1 Dito med Skiepp, 7 dlr; 1 Dito med Ostror, 6 dlr; 1 Dito med Ost och Brödh, 5 dlr; 2 st. Dito med Skoug, 12 dlr [1 Dutch painting with Simsons History, 9 dlr; 1 ditto with ship, 7 dlr; 1 ditto with oysters, 6 dlr; 1 ditto with cheese and bread, 5 dlr; 2 piece ditto with forest, 12 dlr] | Susanna de Merle, wife of Herman Fux, admirality barber |

| 1709 | - | 1 Stoort Hollandz Schillerie, Landskap, 12 dlr; 6 st. Hållenska Schillerier på bräder, 18 dlr [1 large Dutch painting, landscape, 12 dlr; 6 pieces Dutch paintings on panels, 18 dlr] | Donat Feif the Younger, alderman of the goldsmiths |

| unknown | - | 10 Hollenska taflor, 151 dlr [10 Dutch paintings, 151 dlr] | Judith Rokes, wife of Henrik Leijel, merchant |

| 1711 | - | 4 st. Hollenska mindre [schillerier], 240 dlr [4 piece Dutch smaller paintings, 240 dlr] | Johan Johansson Pontin, commisary |

| 1711 | - | 4 aflånga holländska Schillerier, 48 dlr [4 elongated Dutch paintings, 48 dlr] | Reinhold de Croll, court musician |

| 1715 | - | 3 små hållenska målningar, 9 dlr [3 small Dutch paintings, 9 dlr] | Jacob Boll, gold smith |

| 1720 | - | 12 st. hollänska schillerier, 144 dlr [12 piece Dutch paintings, 144 dlr] | Adolf Norden |

| 1727 | - | 2 holländska landtstycken, 24 dlr [2 Dutch landscapes, 24 dlr] | Augusta Elisabet Grill, daughter of the mayor, wife of director of the surgical society Evald Ribe |

| 1728 | - | 2 st. stora hollenska Blomstycken, 36 dlr [2 large Dutch flower pieces, 36 dlr] | Danckwardt Pasch from Lubeck, alderman in the painter’s office |

| 1728 | - | 3 st. stora hollänska stycken, 36 dlr [3 large Dutch pieces, 36 dlr] | Martin Bellman, wine merchant |

| 1729 | - | 1 stort holl. stycke i perspektiv och 2 st. blomstycken, 30 dlr; 2 st. hollenska stycken, 12 dlr; Ett bredt och longt holl. stycke och 3 blomstycken, 20 dlr [1 large Dutch piece in perspective and 2 flower pieces, 30 dlr; 2 Dutch pieces, 12 dlr; one wide and long Dutch piece and 3 flower pieces, 20 dlr] | Johan Glock, winemerchant |

| 1731 | - | 1 holländskt stycke på trä med en biblisk historia [1 Dutch piece on wood with a biblical story] | Heir of Benkt Pihlgren, tapestry maker (d. 1713) |

| 1731 | - | 5 st. små hollendska Schillerier, 30 dlr [5 small Dutch paintings, 30 dlr] | Christoper Christmas, alderman of painters |

| 1731 | - | 8 st. större och mindre hollenska taflor, 48 dlr [8 pieces larger and smaller Dutch paintings, 48 dlr] | Hans Sifvers, stamp master |

| 1737 | - | 15 st. Aflånga holländska Schillerier, 48 dlr [15 elongated Dutch paintings, 48 dlr] | Anna M. widow of Jacob Mischell, chefcook |

| 1739 | - | 1 Holländskt stycke målat på trä, Abraham då han skulle offra sin son, 6 dlr; 1 dito dito, Israels Barns gång genom Röda hafwet, 6 dlr [1 Dutch piece painted on wood, Abraham who sacrifices his son, 6 dlr; 1 dito dito, the children of Israel cross the Red Sea, 6 dlr] | Zacharias Folchers, court auditor |

| 1745 | - | 1 Holländskt stycke, som föreställer de tre män i den brinande ugnen, 12 dlr; 2 större och 2 smärre holländska stycken på trä, 12 dlr [1 Dutch piece, depicting the three men in the burning furnace, 12 dlr; 2 large and 2 small Dutch paintings on wood, 12 dlr] | Johan Daniel Bergman, court jeweller |

| 1747 | - | 1 fyrkantigt gammalt holländskt stycke, 4 dlr [1 octagon old Dutch piece, 4 dlr] | Charlotta Eek, wife of Karl Fredrik Ribes, assessor |

| Source: Granberg, Svenska konstsamlingarnas, vol. 2. Tavlor/Taflor can be translated as “board,” “panel,” or “painting.” For clarity in this table, this term has been translated as “paintings”, though in some cases they may also refer to print boards. |

|||

The Swedish trade city of Gothenburg was not on the Baltic Sea but instead had a direct connection to the North Sea. Gothenburg was founded in 1621 by King Gustav II Adolf (r. 1611–1632) to strengthen Sweden’s economic and strategic position. Dutch, Germans, and Scots were employed in the construction and organization of the city, and the Dutch were by far the most numerous. In the first decades they even had political power in the city, introducing Dutch law and the Dutch language. The recent publication Privat Konsmarknad 1650–1750: Konstsamlingar hos Götheborgsbor och Göteborgskonstnärer (Private art market 1650–1750: art collections of Gothenburg residents and artists) discusses the art objects found in Gothenburg inventories, which have been preserved from 1663 onward.41 In total, 107 probate inventories are preserved for the period 1663–1705, of which forty-six inventories, or 43 percent, list paintings.42 Few of the 612 paintings listed in these inventories are described by their subjects; most often they are simply recorded as skillerÿ (painting), tafla (board), or conterfej (portrait or picture). In some cases, however, they are listed as being Dutch, with or without their subjects.43 That a larger part of these must have come from the Dutch Republic can be concluded from the Gothenburg tolagsräkenskaper (additional customs account). These accounts registered imports into the city, including art objects such as paintings, tapestries, mirrors, and even a pulpit from Stralsund. Paintings were typically recorded in small quantities, with up to ten pieces per shipment; the largest recorded import occurred in 1662, when Mattis van Velden brought forty paintings from Amsterdam. Some of the imported paintings came from Hamburg and Lübeck, and one from London, but most, ninety-three in total, were imported from Amsterdam.44

Immigrant communities

The presence of Dutch paintings in Danish and Swedish inventories reflects a larger pattern of Dutch influence in the Baltic region, where Dutch immigrants settled in significant numbers. Even though we know the names of the painting owners, included in Tables 1 and 2, it is more complicated to determine whether these individuals were in fact immigrants. The names were often recorded by Danish- or Swedish-born scribes, who used the spelling conventions of their own languages and thus made them read as “local.” Determining the immigrant status of these owners would require extensive biographical research, which is beyond the scope of this study due to the challenge of accessing primary sources in Denmark and Sweden. The aforementioned Urban Diaspora project has undertaken such research, combining archeology with archival sources to identify whether the inventories they studied were from immigrant households. Although that project focuses primarily on cultural items like porcelain and faience, we may assume similar trends for paintings.

Archeological excavations in immigrant communities in Danish and Swedish cities have uncovered Dutch pottery, faience, earthenware, and tiles. Research into probate inventories has revealed that 90 percent of people who owned such cultural goods in Helsingør and Aalborg before 1640 were of immigrant descent.45 Most of these owners were Dutch; some were German; and a few were originally from England or Scotland. These goods circulated through the immigrant communities via kinship and business networks extending back to the Netherlands.46

The cultural goods in immigrant homes were not necessarily valuable but were nevertheless appreciated for their design, fashion, and novelty, and especially as links to the homeland. This is evident, as Jette Linaa argues, in the difference in display of these objects between immigrants and the Danish-born elite, who started to own cultural goods from 1640 onward. In the immigrant homes, faience, stoneware, and porcelain were kept in the front room, where paintings were also often found, or in private chambers. The front room, visible from the street, showcased these items publicly. In a private chamber, the members of the household might spend time together among these objects. This suggests that the objects had emotional significance, regardless of their monetary value, and that their owners considered them as ways to recreate the ancestral home and relate to the homeland. In contrast, Danish-born owners kept such goods in kitchens or among iron items, indicating that for them they were mere utility objects.

It is possible that the Dutch paintings in Danish and Swedish inventories should be interpreted as part of this broader export of cultural items that primarily catered to Dutch immigrant communities. The first immigrants may have brought some paintings with them. Maritime ties and family connections in the Dutch Republic ensured additional supply. Over time, the tastes of Dutch immigrants began to shape local consumption and drive a growing market for Dutch goods. As such, these communities contributed to the dispersal of Dutch art and artisanal products across the region. The effects of Dutch imports on regional consumption patterns were even visible in smaller towns in southern Norway, then part of Denmark, where early modern inventories list Dutch cabinets and chests filled with Dutch linen and faience, Dutch glazed and decorated tiles, and paintings and prints on the walls.47

A similar pattern, although with a significant difference, was observed by Eric Jan Sluijter regarding the influx of Flemish immigrants in the Dutch Republic at the turn of the seventeenth century.48 Flemish immigrants brought with them a cultural practice of decorating homes with paintings, creating a strong demand for accessible, affordable art. Initially, this demand was met with imports from Antwerp, but as this practice caught on with the local population, it spurred Dutch painters to innovate and adapt, fueling the rapid growth of painting production in the Dutch Republic in the early seventeenth century. In Denmark and Sweden, by contrast, this effect is not observed; local production of paintings, apparently minimal to start with, does not seem to have increased in response to demand, which suggests that imports largely satisfied this niche without prompting local artistic innovation.

Sound Toll and Customs Rolls

The prevalence of Dutch paintings in inventories throughout Danish and Swedish cities, and the large immigrant communities in these areas, underscore that there was a demand for these works but do not clarify the mechanisms by which these artworks entered local markets. To explore whether these transactions were part of a larger, structured export system, as in the case of exports from Antwerp, we must turn to additional sources of evidence, such as trade registers and customs records, which provide glimpses—often incomplete—into the flow of artworks during this period.

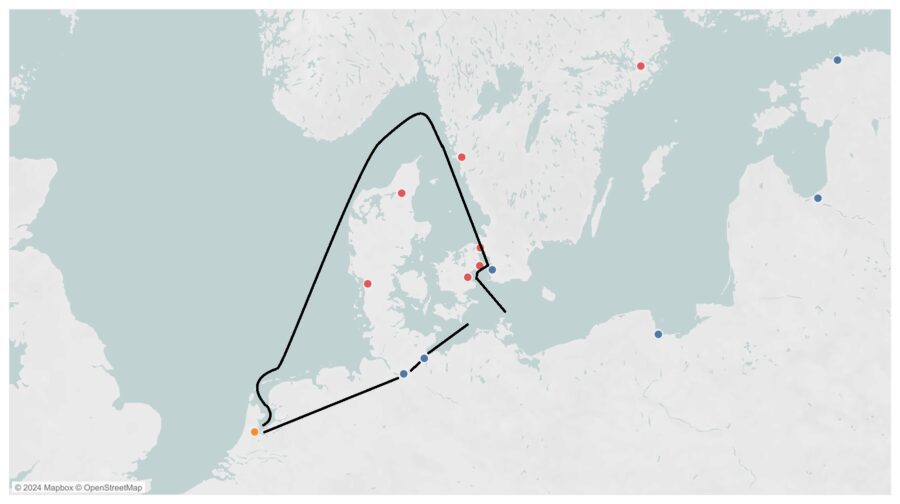

The main sea route from the Dutch Republic to the Baltic Sea passed through the narrow Sound, which was under Danish control (fig. 9). All trade ships passing through were required to stop in Helsingør and pay a toll to the Danish crown.49 The Sound Toll Registers are the official records of this toll. For each ship, toll officials recorded the date, the name of the shipmaster, the shipmaster’s place of residence, the port of departure, the port of destination (from the mid-1660s on), the composition of the cargo, and the toll levied. Cargo recording was based primarily on documents carried aboard the ships, which made it vulnerable to fraud. If officials were suspicious about the shipmaster’s declarations, they had the authority to search the vessel, reportedly done in a sometimes aggressive manner. The Danish crown had first rights on goods that passed through the Sound, and on that authority Christian IV confiscated four chests with pictures from a Dutch ship in 1619.50

The Sound toll tariffs were recorded in custom rolls listing the primary import and export products, including fish, grains, metals, ammunition, woodwares, skins, and fabrics. These rolls do not list decorative goods, with one odd exception: small, painted chests known as formalede skrin in Danish and geschilderde kiskens in Dutch.51

The Sound Toll Registers are digitally accessible through the open-access database Sound Toll Registers Online (STRO), in both transcriptions and scanned images, and can be text-searched for specific commodities.52 Table 3 presents the seventeenth-century Sound Toll records that explicitly mention paintings.53 Throughout the seventeenth century, paintings were recorded on twenty-nine ships passing through the Sound—twenty-three of these sailed directly from the Dutch Republic. Table 3 also includes ships with paintings that sailed to the Baltic Sea from Hamburg (1625), Dieppe (1635), London (1637), Dover (1642), and Bremen (1645). Notably, the ship from Dantzig (1638) sailed toward the North Sea instead of departing for the Baltic.

Table 3 - Ships listed with paintings on board in the Sound Toll Registers (1600-1700), in chronological order

| Date (m/d/y) | Shipmaster | Departure | Destination* | Paintings on board | STR Recorded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7/26/1620 | Hyge Issbrantssen | Amsterdam | - | for 1733 daler malerier, reffschindt och allehaande cramerie [1733 rigsdaler worth of paintings, fox hides and a variety of peddler’s goods] | 4111443 |

| 9/20/1625 | Dirrich Hendrichsen | Hamburg | - | for 300 dr. schilderie och trævare fremmedt goedz [300 rigsdaler worth of paintings and products of wood foreign goods] | 4005664 |

| 12/13/1627 | Klaus Kypper | Schermerhorn | - | 400 dr. gaaren och schildarij [400 rigsdaler worth of yarn and paintings] | 4005842 |

| 2/18/1628 | Thioerdt Peiterssen | Vlieland | - | 950 dr. Garen, lerridt och Schilderij [950 rigsdaler worth of yarn, linnen and paintings] | 4052980 |

| 5/24/1629 | Petter Siffuersen | Stavoren | - | 1203 daller Sengetøygh, Kister, Telercken, Flaschen, Glas och Schillerij [1203 rigsdaler worth of bedding, chests, plates, bottles, glass and paintings] | 4237044 |

| 8/4/1634 | Dyrich Janssen | Krommeniedijk | - | 7 støcker schilerij och 4 kortt [7 pieces of painting and 4 maps] | 899635 |

| 5/27/1635 | Adrian Clausen | Holland | [Stockholm] | 120 rd hatte och schilderi [120 rigsdaler worth of hats and paintings] | 845275 |

| 4/28/1635 | Johan Banay | Dieppe, France | [Copenhagen] | Contrafeijer for 25 dr [paintings with a value of 25 rigsdaler] | 844501 |

| 6/12/1635 | Sinurt Jansen Bussmas | Schermerhorn | [Copenhagen] | for 230 rd schilerij och craemmerij [230 rigsdaler worth of paintings and peddler’s goods] | 893008 |

| 4/7/1636 | Herman Pietersen | Stavoren | - | 13 dr. Schilderi [13 rigsdaler worth of paintings] | 866460 |

| 5/18/1636 | Cornelis Dowesen | Terschelling | - | 1820 dr. krammerij, drogerij och malerij [1820 rigsdaler worth of peddler’s goods, medicines and paintings] | 869769 |

| 5/29/1636 | Peter Jauen | Stavoren | - | 58 Dr. Endtwerck och schilderi [58 rigsdaler worth of manufactured items and paintings] | 873294 |

| 6/11/1636 | Siemen Klausen | Assendelft | [Stockholm] | skilderi och muersten for Sr. Pontus de la Garda sweriges regis marskalck 2000 rd [paintings and building stones or bricks for Mr. Pontus de la Gardie, Marshal of the King of Sweden, with a value of 2000 rigsdaler] | 851901 |

| 8/4/1636 | Dyrich Janssen | Krommeniedijk | - | 17 støcker schilderij [17 pieces of painting] | 899635 |

| 9/17/1636 | Abbe Berendssen | Molkwerum | - | 107 dr. Schilderi och sukatt [107 daler worth of paintings and succade] | 8564040 |

| 7/22/1637 | Jørgen Jansen | London | - | 6 stk schilderij [6 pieces of painting] | 822894 |

| 6/12/1638 | Isebrandt Pietersen | Amsterdam | [Sweden] | for 100 rixdr. schilderi och andet [100 rigsdaler worth of paintings and other] | 878552 |

| 8/15/1638 | Roleff Geritsen | Dantzig | - | 1 Kase Schilderi och canefass, 100 Dr. [1 chest with paintings and canvas, 100 rigsdaler] | 876168 |

| 6/13/1642 | Cornelliss Tiepkhess | Terschelling | - | for 150 rd schilderier [150 rigsdaler worth of paintings] | 836896 |

| 7/23/1642 | Jann Martin | Dover | - | 2 Støcker schilderij [2 pieces of painting] | 836721 |

| 9/28/1642 | Wiellum Wiellumsen Grott | Vlieland | [Denmark] | for hans Maijst 1000 rd. Schilderij [for His Majesty 1000 rigsdaler worth of paintings] | 800947 |

| 7/14/1643 | Willum Willumsssen Beett | Vlieland | [Denmark] | naaged schilderi till hans Kongs Mst och Hans Førstelige Naade Prindsens Fornøedenhed [several paintings for His Majesty the King and His Royal Highness the Prince’s needs] | 814561 |

| 4/18/1645 | Dirich Baerckhoven | Bremen | - | 270 Dr. Schilderi [270 daler worth of paintings] | 793247 |

| 9/9/1656 | Foppe Albertsen | Amsterdam | - | 450 Rd. Tobach och schilderie [450 rigsdaler worth of tobacco and paintings] | 776435 |

| 10/14/1656 | Jan Hinrichsen Graff | Amsterdam | - | for 150 rd schilderier [150 rigsdaler worth of paintings] | 784608 |

| 7/7/1665 | Memiert Cornelssenn | Amsterdam | [Aalborg?] | 2 cassen med schilderij [2 cases with paintings] | 717752 |

| 10/13/1668 | Foppe Obbess | Amsterdam | Danzig | for 150 rd. Malderier, hollants goeds, […]lants craamgoeds, hvorpaa er ingen certificasion [150 rigsdaler worth of paintings, Dutch goods, […] peddler’s goods, for which there is no certificate] | 1707836 |

| 11/13/1668 | Jan Jochimssen | Amsterdam | Danzig | for 100 Rdr malderye oc cramerye [100 rigsdaler worth of paintings and peddler’s goods] | 1709431 |

| 11/2/1669 | Claess Sipkes | Amsterdam | [Copenhagen] | 1 cassa med schilderier, 1 cassa med marmersteen, tilhörende hans Kongl Maijt [1 chest with paintings, 1 chest with marble, belonging to His Royal Majesty] | 1714955 |

| Source: Sound Toll Registers Online, www.soundtoll.nl Rd / dr = rigsdaler * = Destination listed when specified, between brackets when it can be deduced from the rest of the text Note: the transcriptions and values are based on the scans of the original and not on the transcriptions published in the database, which are sometimes incomplete or wrongly transcribed or interpreted. |

||||

Inconsistencies in how paintings are recorded in the Sound Toll Registers prevent a comprehensive understanding of their volume and scope. The paintings on board were recorded in four different ways: by number of paintings (“17 støcker schilderij” [17 pieces of painting]) in 1636, by number of chests (“2 cassen med schilderij” [2 chests with paintings]) in 1665, by value (“for 150 rigsdaler schilderier” [150 rigsdaler worth of paintings]) in 1665, or by value together with other goods (“for 230 rigsdaler schilerij och craemmerij” [230 rigsdaler worth of paintings and peddler’s goods]) in 1635. The latter method was the most common. Paintings were grouped with items like linen, yarn, hats, silk, fox hides, tobacco, “wooden objects,” and “Dutch goods,” but most frequently with the general craemmerij, craamgoeds (peddler’s goods), which were not further specified. As these luxury goods formed a minor part of the overall cargo and shared the same toll rate, they were recorded together. This practice suggests that the many hundreds of records listing unspecified cases of peddler’s goods and kiøbmandschab (merchant’s goods) may have included paintings as well.

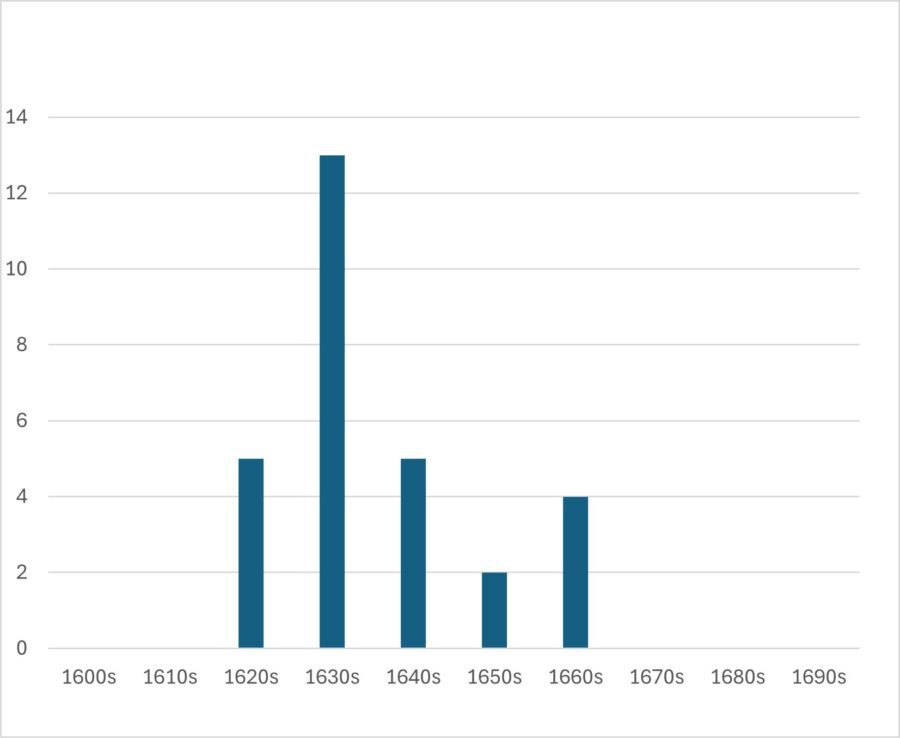

Ships with paintings on board recorded in the Sound Toll Registers per decade

Figure 10 illustrates how many ships were recorded with paintings on board in each decade of the seventeenth century. Notably, the data show no records in either the early decades of the century or after 1669. Most decades show a low frequency, between two and five ships. The exception is the 1630s, with thirteen ships documented as carrying paintings. This small peak might reflect a temporary surge in demand, favorable trade conditions in the 1630s, or perhaps changes in administrative practices that prompted more detailed recording. The absence of records after 1669 is striking and could perhaps be partially explained by political and economic disruptions caused by conflicts like the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678) and the Scanian War (1675–1679). Other undocumented explanations are also possible, including, again, changes in administrative practices, perhaps that paintings were no longer registered separately but fell under the general categories of peddler’s goods and merchant’s goods.

The Sound Toll Registers provide a picture of the sporadic export of paintings through the Sound, which appears much smaller in scale and scope to Flemish exports. For example, the total number of twenty-nine ships recorded as carrying paintings through the Sound pales in comparison with the numbers produced by Claartje Rasterhoff and Filip Vermeylen based on the Tol van Zeeland (Zeeland Toll records).54 The researchers used these toll books to investigate the extent of luxury exports from Antwerp to the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century. They documented a total of 668 shipments with paintings across fourteen random sample years between 1630 and 1700. Although not comparable to toll registers, the records of Flemish dealer Guilliam Forchondt (1608–1678) also provide valuable insight into the volume of Flemish painting exports. Between 1643 and 1678, Forchondt exported nearly ten thousand paintings, most of which were destined for the Iberian Peninsula.55

With only a few exceptions, the Sound Toll Registers do not provide insights into whether the paintings that passed the strait were commissioned or shipped on speculation by art dealers or merchants. One of those exceptions is a record from 1636, specifying that 2,000 rigsdaler worth of paintings and muersten (building stones or bricks) were intended for the Swedish Marshal Jakob de la Gardie (1583–1652). These were probably ordered for his Stockholm palace, Makalös, then under construction. The inventories drawn up of the palace unfortunately do not provide details about the paintings that were part of this shipment.56

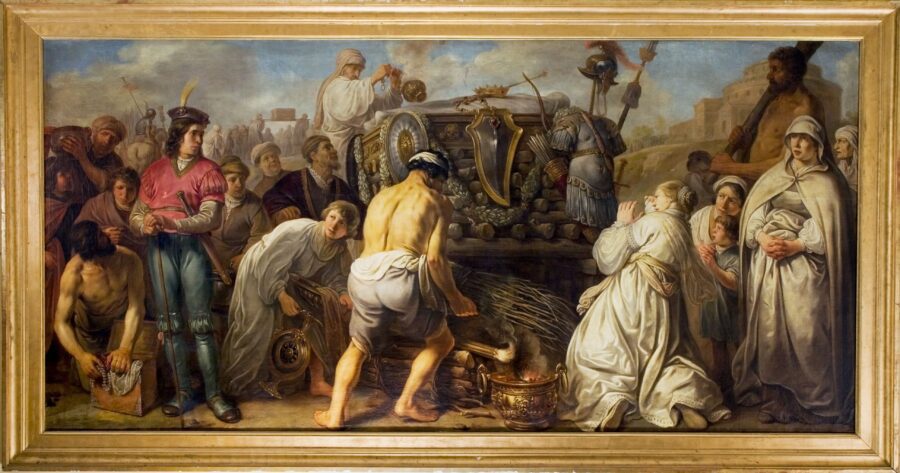

Three other records specify the Danish crown as the intended recipient. In 1642, Wiellum Wiellumsen Grott transported paintings worth 1,000 rigsdaler, followed by another shipment of “several paintings” in 1643, all destined for Christian IV. These were likely meant for the redecoration of the Great Hall at Kronborg Slot, a project in progress during the early 1640s. The hall was to feature eighty-four scenes of heroic events in Danish history, based on designs drawn between 1637 and 1639. The project leader, the Dutch engraver/ draughtsman Simon de Passe (1595–1647), commissioned prominent painters such as Gerard van Honthorst (1592–1656), Claes Moeyaert (1592–1655), Isaac Isaacsz. (1598–1649), Simon Peter Tilman (1601–1668), Adriaen van Nieulandt, and Salomon de Koninck (1609–1656). Of the series, seventeen paintings have survived, of which a number bear dates, either 1640, 1641, or 1643 (fig. 11 and fig. 12).57 Likewise, in 1669, Claess Sipkes, sailing from Amsterdam, transported a case of paintings for Frederik III. This case might have included Ferdinand Bol’s (1616–1680) Portrait of Michiel de Ruyter, believed to have been gifted to the king by De Ruyter himself.58

Several documented deliveries of paintings to the Danish kings do not feature in the Sound Toll Registers, such as the aforementioned 148 paintings bought by Jonas Charisius in the Low Countries in 1607 and 1608, and the 350 paintings bought by Theodorus Rodenburgh in 1621. Other notable examples include the several substantial deliveries of tapestries and paintings to Christian IV from Antwerp between 1614 and 1616 by Adam Baselier, who passed through Dutch territory,59 the forty-six paintings offered to Christian IV by the dealer François Bastiaensz in 1621,60 the gift of twenty-six paintings by Albert Eckhout (ca. 1610–1665) to Frederik III of Denmark (r. 1648–1670) from Johan Maurits in 1654,61 and the purchases made in the Dutch Republic by court artist Toussaint Gelton (ca. 1630–1680) in the 1670s.62

All in all, the Sound Toll Registers provide only limited documentation of the painting trade from the Dutch Republic to Denmark and Sweden, despite the sizable presence of Dutch paintings in inventories. That these records provide an incomplete picture is supported by the Danish customs roll issued on August 13, 1651, which stipulates import taxes per product type. In this roll, for the first time, paintings are specified: “adskillig nyrenbergiske, augsburgiske, frandtz, engelske oc dantziger vare af skilderier, speigel, puppentøig oc alle andre efventyrske kramvare deraf gifvis” (various Nurembergian, Augsburgian, French, English, and Dantziger goods like paintings, mirrors, toys, and all other speculative items of this kind).63 This category groups various cultural goods under a single toll rate by value of the total, supporting the above hypothesis that paintings could have passed otherwise unrecorded through the toll offices under the labels of general peddler’s or merchant’s goods. The list mentions various geographical origins, including France, England, and Dantzig, which also appear in the Sound Toll Registers, but not the Netherlands. This raises further questions about the nature of the painting trade.

We need to consider, for instance, whether a different trade route was preferred for the transport of paintings. The overland route via Hamburg and Lübeck served as a significant alternative for transporting low-weight, low-volume, and expensive commodities, especially during the winter months when the sea was frozen (see fig. 9). The first indication of Hamburg’s possible relevance in the painting trade comes from the aforementioned imports of paintings into Gothenburg during the second half of the seventeenth century. These paintings were not necessarily produced in Hamburg; rather, the city may have served as a transit port. The importance of the overland route is also suggested by the introduction to the toll specification from August 13, 1651, which specified that items identified as “kram oc andre efventyrske vare” (so the same terms as above) delivered by land to public markets and gatherings, or otherwise imported by postmen, must declare their goods at the first customs office they encounter.64 This suggests that, just like in the Dutch Republic, fairs and markets were important outlets for foreign goods, including paintings. This observation supports Linaa’s argument that cultural goods like porcelain and faience, which are rarely listed in shop inventories in Helsingør and Aalborg, were exchanged in more informal settings, such as fairs and markets, and through personal networks.65

Further Research

Probate inventories, toll records, customs rolls, and comparative studies of immigrant communities provide evidence of the ownership and trade of Dutch paintings in seventeenth-century Denmark and Sweden. They all point to the possibility of a structured trade system involving the coordinated production, sale, and shipment of paintings through art dealers’ networks. This organized trade aligns with broader international patterns in the early modern art market, demonstrated by the well-documented case of Flemish exports. However, the Sound Toll Registers provide only limited evidence for the trade in paintings from the Dutch Republic to Denmark and Sweden. A comprehensive picture of the scale, structure, and cultural significance of the Dutch painting trade in the Baltic remains elusive due to the lack of systematic records and detailed archival sources.

To understand fully the predominance of Dutch paintings in Danish and Swedish households, future research should address several key areas. First, extensive archival research should extend this inquiry to other trade towns and cities with large immigrant populations along the Baltic Sea, such as Lübeck, Malmö, Danzig, Riga, and Reval (fig. 13). Additional probate inventories, customs rolls, and toll records may clarify the extent of this trade. Preliminary findings from inventories in Danzig, Lübeck, and Reval already indicate the presence of paintings in households, although their origins are not specified.66

Second, a systematic study of inventories in this region, combined with biographical research into their owners, could yield further insights into the cultural role of paintings in the Baltic region, and the ownership of Dutch paintings specifically. Distinctions between immigrant and native ownership, between middle-class owners and the nobility, and between urban trade hubs, court cities, and smaller towns deserve further exploration to better understand the varying contexts of painting ownership and display.

Mapping the trade routes that carried paintings from the Dutch Republic to the Baltic is another critical avenue of research. Future studies should investigate a combination of sources, such as chartering contracts, toll registers, and customs archives in both the Dutch Republic and key Baltic trade cities, to better understand the size and scope of the painting trade.67 Alternative routes bypassing the expensive tolls of the Sound, such as overland transport through Hamburg and Lübeck, should be further explored, as should the possibility that paintings were sent by post, a method frequently used for smaller luxury goods.68

Insights into the practicalities of the painting trade may also be gained from further research into the individuals who sold paintings in the region: for example, the Amsterdam dealer Jan de Kaersgieter (ca. 1602/3–1661), who delivered paintings worth 1,287 guilders to Melchior Jungh (ca. 1615–1678) in Stockholm in 1641, as recorded in unsuccessful payment requests by his heirs,69 or the dealer Jean Carpentier Danneux (1618–1670), who in 1652 sent five paintings by Wallerant Vaillant (1623–1677) to Stockholm.70

There is also documentation about art dealers who operated in more than one location in the region. The previously mentioned Caspar de Cocquiel, for example, requested permission from the city of Danzig to sell paintings in 1693 and also applied for citizenship in Copenhagen to sell paintings in 1696, suggesting that De Cocquiel was testing out different markets in the region.71 In 1693, the Antwerp art dealers Jan Peter Tassaert (1651–1725), Christiaen de Busson (d. 1733), and Jan Baptist op de Laeij (d. 1735) founded a company to sell paintings in Denmark, Sweden, Poland, and Brandenburg, with which they were active until 1702.72 Interestingly, these Flemish dealers operating in the area by the end of the seventeenth century raise questions as to whether these “hollandsk” paintings in inventories were exclusively Dutch.

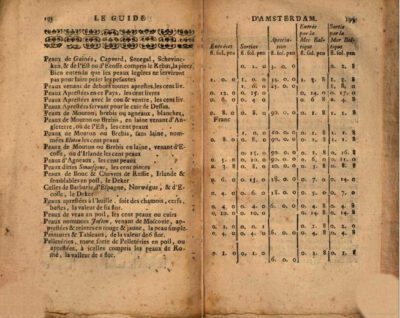

Finally, new research should extend to the eighteenth century. The explicit inclusion of paintings in eighteenth-century tariff schedules for goods entering and leaving the Dutch Republic suggests that paintings were recognized as trade goods with economic importance (fig. 14).73 The mentions of “peintures et tableaux, de la valeur de 6 flor[ins]” (paintings and pictures, valued at 6 florins) and “tableaux de toutes sortes avec leurs bois, non enrichis, de la valeur de six florins” (paintings of all kinds, with their wooden frames, not embellished, valued at six florins) indicate that paintings were taxed based on their declared value. In addition to the entry and exit taxes for the Dutch Republic, the list specifies a different tax for goods shipped from or bound for the Baltic region. These early eighteenth-century sources may indicate a maturation of the international painting trade, particularly in relation to the Dutch Republic and the Baltic region. This does not correspond with the evidence from the Sound Toll Registers, which shows recorded shipments of paintings dwindling after 1669, but it does align with Michael North’s pioneering research on the collecting of Dutch paintings in the Baltic area during the following century.74

The links between art dealers, trade networks, and immigrant communities offer rich possibilities for further exploration. By combining a variety of archival sources and expanding research to other Baltic towns, it may be possible to more fully reconstruct the movement and impact of Dutch paintings in this region.